Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

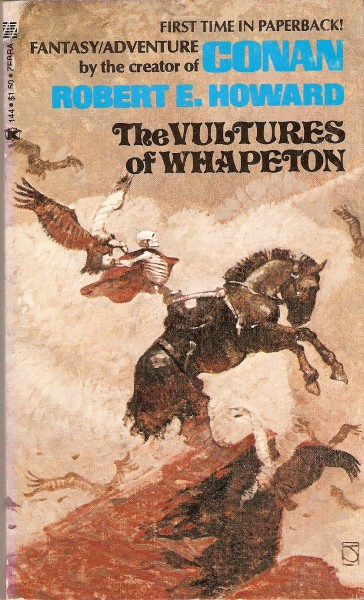

Published in The Vultures of Whapeton, 1975.

Written in 1933, the story is set in the region of “Lost Knob,” the fictional version of Howard’s home town of Cross Plains. Thirty miles

south lies the larger town of Brownwood (“Bisley”), where Howard had attended his final year of high school and two years of commercial

courses. In 1931, work began on a dam eight miles north of Brownwood to impound water from the Pecan Bayou and Jim Ned Creek to

create a reservoir. Engineers had estimated that it would take two years, at the normal rate of rainfall, to fill the reservoir. But on July 3, 1932,

a torrential rain fell over the area, and the entire reservoir was filled, 7,000 acres filled to an average depth of more than twenty feet, in just

six hours. It was the equivalent of suddenly diverting the flow of Niagara Falls into the watershed of the two small creeks. The story also

speaks eloquently of where Howard’s sympathies resided during the Depression.

Saul Hopkins was king of Locust Valley, but kingship never turned hot lead. In the wild old days, not so long distant, another man was king of the Valley, and his methods were different and direct. He ruled by the guns, wire-clippers and branding irons of his wiry, hard-handed, hard-eyed riders. But those days were past and gone, and Saul Hopkins sat in his office in Bisley and pulled strings to which were tied loans and mortgages and the subtle tricks of finance.

Times have changed since Locust Valley reverberated to the guns of rival cattlemen, and Saul Hopkins, by all modern standards, should have lived and died king of the Valley by virtue of his gold and lands; but he met a man in whom the old ways still lived.

It began when John Brill’s farm was sold under the hammer. Saul Hopkins’ representative was there to bid. But three hundred hard-eyed ranchers and farmers were there, too. They rode in from the river bottoms and the hill country to the west and north, in ramshackle flivvers, in hacks, and on horseback. Some of them came on foot. They had a keg of tar, and half a dozen old feather pillows. The representative of big business understood. He stood aside and made no attempt to bid. The auction took place, and the farmers and ranchers were the only bidders. Land, implements and stock sold for exactly $7.55; and the whole was handed back to John Brill.

When Saul Hopkins heard of it, he turned white with fury. It was the first time his kingship had ever been flouted. He set the wheels of the law to grinding, and before another day passed, John Brill and nine of his friends were locked in the old stone jail at Bisley. Up along the bare oak ridges and down along the winding creeks where poverty-stricken farmers labored under the shadow of Saul Hopkins’ mortgages, went the word that the scene at Brill’s farm would not be duplicated. The next foreclosure would be attended by enough armed deputies to see that the law was upheld. And the men of the creeks and the hills knew that the promise was no idle one. Meanwhile, Saul Hopkins prepared to have John Brill prosecuted with all the power of his wealth and prestige. And Jim Reynolds came to Bisley to see the king.

Reynolds was John Brill’s brother-in-law. He lived in the high postoak country north of Bisley. Bisley lay on the southern slope of that land of long ridges and oak thickets. To the south the slopes broke into fan shaped valleys, traversed by broad streams. The people in those fat valleys were prosperous; farmers who had come late into the country, and pushed out the cattlemen who had once owned it all.

Up on the high ridges of the Lost Knob country, it was different. The land was rocky and sterile, the grass thin. The ridges were occupied by the descendants of old pioneers, nesters, tenant farmers, and broken cattlemen. They were poor, and there was an old feud between them and the people of the southern valleys. Money had to be borrowed from somebody of the latter clan, and that intensified the bitterness.

Jim Reynolds was an atavism, the personification of anachronism. He had lived a comparatively law-abiding life, working on farms, ranches, and in the oil fields that lay to the east, but in him always smoldered an unrest and a resentment against conditions that restricted and repressed him. Recent events had fanned these embers into flame. His mind leaped as naturally toward personal violence as that of the average modern man turns to processes of law. He was literally born out of his time. He should have lived his life a generation before, when men threw a wide loop and rode long trails.

He drove into Bisley in his Ford roadster at nine o’clock one night. He stopped his car on French Street, parked, and turned into an alley that led into Hopkins Street—named for the man who owned most of the property on it. It was a quirk in the man’s nature that he should cling to the dingy little back street office in which he first got his start.

Hopkins Street was narrow, lined mainly with small offices, warehouses, and the backs of buildings that faced on more pretentious streets. By night it was practically deserted. Bisley was not a large town, and except on Saturday night, even her main streets were not thronged after dark. Reynolds saw no one as he walked swiftly down the narrow sidewalk toward a light which streamed through a door and a plate glass window.

There the king of Locust Valley worked all day and late into the night, establishing and strengthening his kingship.

The grim old warrior who had kinged it in the Valley in an earlier generation knew the men he had to deal with. He wore two guns in loose scabbards, and cold-eyed gunmen rode with him, night or day. Saul Hopkins had dealt in paper and figures so long he had forgotten the human equation. He understood a menace only as a threat against his money—not against himself.

He bent over his desk, a tall, gaunt, stooped man, with a mop of straggly grey hair and the hooked nose of a vulture. He looked up irritably as some one bulked in the door that opened directly on the street. Jim Reynolds stood there—broad, dark as an Indian, one hand under his coat. His eyes burned like coals. Saul Hopkins went cold, as he sensed, for the first time in his life, a menace that was not directed against his gold and his lands, but against his body and his life. No word was passed between them, but an electric spark of understanding jumped across the intervening space.

With a strangled cry old Hopkins sprang up, knocking his swivel chair backward, stumbling against his desk. Jim Reynolds’ hand came from beneath his coat gripping a Colt .45. The report thundered deafeningly in the small office. Old Saul cried out chokingly and rocked backward, clutching at his breast. Another slug caught him in the groin, crumpling him down across the desk, and as he fell, he jerked sidewise to the smash of a third bullet in his belly. He sprawled over the desk, spouting blood, and clawing blindly at nothing, slid off and blundered to the floor, his convulsive fingers full of torn papers which fell on him in a white, fluttering shower from the blood splashed desk.

Jim Reynolds eyed him unemotionally, the smoking gun in his hand. Acrid powder fumes filled the office, and the echoes seemed to be still reverberating. Whistling gasps slobbered through Saul Hopkins’ grey lips and he jerked spasmodically. He was not yet dead, but Reynolds knew he was dying. And galvanized into sudden action, Reynolds turned and went out on the street. Less than a minute had passed since the first shot crashed, but a man was running up the street, gun in hand, shouting loudly. It was Mike Daley, a policeman. Reynolds knew that it would be several minutes, at least, before the rest of the small force could reach the scene. He stood motionless, his gun hanging at his side.

Daley rushed up, panting, poking his pistol at the silent killer.

“Hands up, Reynolds!” he gasped. “What the hell have you done? My God, have you shot Mr. Hopkins? Give me that gun—give it to me.”

Reynolds reversed his .45, dangling it by his index finger through the trigger guard, the butt toward Daley. The policeman grabbed for it, lowering his own gun unconsciously as he reached. The big Colt spun on Reynolds’ finger, the butt slapped into his palm, and Daley glared wild eyed into the black muzzle. He was paralyzed by the trick—a trick which in itself showed Reynolds’ anachronism. That roll, reliance of the old time gunman, had not been used in that region for a generation.

“Drop your gun!” snapped Reynolds. Daley dumbly opened his fingers and as his gun slammed on the sidewalk, the long barrel of Reynolds’ Colt lifted, described an arc and smashed down on the policeman’s head. Daley fell beside his fallen gun, and Reynolds ran down the narrow street, cut through an alley and came out on French Street a few steps from where his car was parked.

Behind him he heard men shouting and running. A few loiterers on French Street gaped at him, shrank back at the sight of the gun in his hand. He sprang to the wheel and roared down French Street, shot across the bridge that spanned Locust Creek, and raced up the road. There were few residences in that end of town, where the business section abutted on the very bank of the creek. Within a few minutes he was in open country, with only scattered farmhouses here and there.

He had not even glanced toward the rock jail where his friends lay. He knew the uselessness of an attempt to free them, even were it successful. He had only followed his instinct when he killed Saul Hopkins. He felt neither remorse nor exultation, only the grim satisfaction of a necessary job well done. His nature was exactly that of the old-time feudist, who, when pushed beyond endurance, killed his man, took to the hills and fought it out with all who came against him. Eventual escape did not enter his calculations. His was the grim fatalism of the old time gun fighter. He merely sought a lair where he could turn at bay. Otherwise he would have stayed and shot it out with the Bisley police.

A mile beyond the bridge the road split into three forks. One led due north to Sturling, whence it swung westward to Lost Knob; he had followed that road, coming into Bisley. One led to the north west, and was the old Lost Knob road, discontinued since the creation of Bisley Lake. The other turned westward and led to other settlements in the hills.

He took the old north west road. He had met no one. There was little travel in the hills at night. And this road was particularly lonely. There were long stretches where not even a farm house stood, and now the road was cut off from the northern settlements by the great empty basin of the newly created Bisley Lake, which lay waiting for rains and head rises to fill it.

The pitch was steadily upward. Mesquites gave way to dense postoak thickets. Rocks jutted out of the ground, making the road uneven and bumpy. The hills loomed darkly around him.

Ten miles out of Bisley and five miles from the Lake, he turned from the road and entered a wire gate. Closing it behind him, he drove along a dim path which wound crookedly up a hill side, flanked thickly with postoaks. Looking back, he saw no headlights cutting the sky. He must have been seen driving out of town, but no one saw him take the north west road. Pursuers would naturally suppose he had taken one of the other roads. He could not reach Lost Knob by the north west road, because, although the lake basin was still dry, what of the recent drouth, the bridges had been torn down over Locust Creek, which he must cross again before coming to Lost Knob, and over Mesquital.

He followed a curve in the path, with a steep bluff to his right, and coming onto a level space strewn with broken boulders, saw a low-roofed house looming darkly ahead of him. Behind it and off to one side stood barns, sheds and corrals, all bulked against a background of postoak woods. No lights showed.

He halted in front of the sagging porch—there was no yard fence—and sprang up on the porch, hammering on the door. Inside a sleepy voice demanded his business.

“Are you by yourself?” demanded Reynolds. The voice assured him profanely that such was the case. “Then get up and open the door; it’s me—Jim Reynolds.”

There was a stirring in the house, creak of bed springs, prodigious yawns, and a shuffling step. A light flared as a match was struck. The door opened, revealing a gaunt figure in a dingy union suit, holding an oil lamp in one hand.

“What’s up, Jim?” demanded the figure, yawning and blinking. “Come in. Hell of a time of night to wake a man up—”

“It ain’t ten o’clock yet,” answered Reynolds. “Joel, I’ve just come from Bisley. I killed Saul Hopkins.”

The gaping mouth, in the middle of a yawn, clapped shut with a strangling sound. The lamp rocked wildly in Joel Jackson’s hand, and Reynolds caught it to steady it.

“Saul Hopkins?” In the flickering light Jackson’s face was the hue of ashes. “My God, they’ll hang you! Are they after you? What—”

“They won’t hang me,” answered Reynolds grimly. “Only reason I run was there’s some things I want to do before they catch me. Joel, you’ve got reasons for befriendin’ me. I can’t hide out in the hills all the time, because there’s nothin’ to eat. You live here alone, and don’t have many visitors. I’m goin’ to stay here a few days till the search moves into another part of the country, then I’m goin’ back into Bisley and do the rest of my job. If I can kill that lawyer of Hopkins’ and Judge Blaine and Billy Leary, the chief of police, I’ll die happy.”

“But they’ll comb these hills!” exclaimed Jackson wildly. “They can’t keep from findin’ you—”

“Hang on to your nerve,” grunted Reynolds. “We’ll run my car into that ravine back of this hill and cover it up with brush. Take a regular bloodhound to find it. I’ll stay in the house here, or in the barn, and when we see anybody comin’, I’ll duck out into the brush. Only way they can get here in a car is to climb that foot path like I did. Besides, they won’t waste much time huntin’ this close to Bisley. They’ll take a sweep through the country, and if they don’t find me right easy, they’ll figger I’ve made for Lost Knob. They’ll question you, of course, but if you’ll keep your backbone stiff and look ’em in the eye when you lie about it, I don’t think they’ll bother to search your farm.”

“Alright,” shivered Jackson, “but it’ll go hard with me if they find out.” He was numbed by the thought of Reynolds’ deed. It had never occurred to him that a man as “big” as Saul Hopkins could be shot down like an ordinary human.

Little was said between the men as they drove the car down the rocky hillside and into the ravine; wedged into the dense shinnery, they skilfully masked its presence.

“A blind man could tell a car’s been driv down that hill,” complained Jackson.

“Not after tonight,” answered Reynolds, with a glance at the sky. “I believe it’s goin’ to rain like hell in a few hours.”

“It is mighty hot and still,” agreed Jackson. “I hope it does rain. We’re needin’ it. We didn’t get no winter seasonin’—”

“What the hell do you care for your crops?” growled Reynolds. “You don’t own ’em; nobody in these hills owns anything. Everything you all got is mortgaged to the hilt—some of it more’n once. You, personally, been lucky to keep up the interest; you sag once, and see what happens to you. You’ll be just like my brother-in-law John, and a lot of others. You all are a pack of fools, just like I told him. To hell with strugglin’ along and slavin’ just to put fine clothes on somebody else’s backs, and good grub into their bellies. You ain’t workin’ for yourselves; you’re workin’ for them you owe money to.”

“Well, what can we do?” protested Jackson. Reynolds grinned wolfishly.

“You know what I done tonight. Saul Hopkins won’t never throw no other man out of his house and home to starve. But there’s plenty like him. If you farmers would listen to me, you’d throw down your rakes and pick up your guns. Up here in these hills we’d make a war out of it that’d make the Bloody Lincoln County War look plumb tame.”

Jackson’s teeth chattered as with an ague. “We couldn’t do it, Jim. Times is changed, can’t you understand? You talk just like them old-time outlaws my dad used to tell me about. We can’t fight with guns like our fathers used to do. The governor’d send soldiers to hunt us down. Keepin’ a man from biddin’ at a auction is one thing; fightin’ state soldiers is another. We’re just licked and got to know it.”

“You’re talkin’ just like John and all the others,” sneered Reynolds. “Well, John’s in jail and they say he’s goin’ to the pen; but I’m free and Saul Hopkins is in hell. What you say to that?”

“I’m afeared it’ll be the ruin of us all,” moaned Jackson.

“You and your fears,” snarled Reynolds. “Men ain’t got the guts of lice no more. I thought, when the farmers took over that auction, they was gettin’ their bristles up. But they ain’t. Your old man wouldn’t have knuckled down like you’re doin’. Well, I know what I’m goin’ to do, if I have to go it alone. I’ll get plenty of them before they get me, damn ’em. Come on in the house and fix me up somethin’ to eat.”

Much had been crowded into a short time. It was only eleven o’clock. Stillness held the land in its grip. The stars had been blotted out by a grey haze-like veil which, rising in the north west, had spread over the sky with surprizing speed. Far away on the horizon lightning flickered redly. There was a breathless tenseness in the air. Breezes sprang up, blew fitfully from the south east, and as quickly died down. Somewhere off in the wooded hills a night bird called uneasily. A cow bawled anxiously in the corral. The beasts sensed an impending something in the atmosphere, and the men, raised in the hills, were no less responsive to the portents of the night.

“Been a kind of haze in the sky all day,” muttered Jackson, glancing out the window as he fumbled about, setting cold fried bacon, corn bread, and a pot of red beans on the rough hewn table before his guest. “Been lightnin’ in the north west since sundown. Wouldn’t be surprized if we had a regular storm. ’Bout that time of the year.”

“Likely,” grunted Reynolds, his mouth full of pork and corn bread. “Joel, dern you, ain’t you got nothin’ to drink better’n buttermilk?”

Jackson reached up into the tin-doored cupboard and brought down a jug. He pulled out the corn-cob stopper and tilted the mouth into a tin cup. The reek of white corn juice filled the room, and Reynolds smacked his lips appreciatively.

“Hell, Joel, you ought not to be scared of hidin’ me, long as you’ve kept that still of your’n hid.”

“That’s different,” muttered Jackson uneasily. “You know, though, I’ll do all I can to help you out.”

He watched his friend in morbid fascination as Reynolds wolfed down the food and gulped the fiery liquor with keen relish.

“I don’t see how you can set there and eat like that. Don’t it make you kind of sick—thinkin’ about Hopkins?”

“Why should it?” Reynolds’ eyes became grim as he set down the cup and stared at his host. “Throwed John out of his home, and him with a wife and kids, and then was goin’ to send him to the pen—how much you think a man ought to take off a skunk like that?”

Jackson avoided his gaze and looked out the window. Away off in the distance came the first low grumble of thunder. The lightning played constantly along the north western horizon, splaying out to east and west.

“Comin’ up sure,” mumbled Jackson. “Reckon they’ll get some water in Bisley Lake. Engineers said it’d take three years to fill it, at the rate of rainfall in this country. I say one big rain like some I’ve seen, would do the job. An awful lot of water can come down Locust and Mesquital.”

He opened the door and went out. Reynolds followed. The breathlessness of the atmosphere was even more intense. The haze-like veil had thickened; not a star was visible. The crowding hills with their black thickets rendered the darkness even more dense; but it was cut by the incessant glare of the lightning—distant, but growing more vivid. In the flashes a long low-lying bank of inky blackness could be seen hugging the north western horizon.

“Funny the laws ain’t been up the road,” muttered Jackson. “I been listenin’ for cars.”

“Reckon they’re searchin’ the other roads,” answered Reynolds. “Take some time to get up a posse after night, anyway. They’ll be burnin’ up the telephone wires. I reckon you got the only phone there is on this road, ain’t you, Joel?”

“Yeah; folks couldn’t keep up the rent on ’em. By gosh, that cloud’s comin’ up slow, but it sure is black. I bet it’s been rainin’ pitch forks on the head of Locust for hours.”

“I’m goin’ to walk down towards the road,” said Reynolds. “I can see a headlight a lot quicker down there than I can up here, for all these postoaks. I’ve got an idea they’ll be up here askin’ questions before mornin’. But if you lie like I’ve seen you, they won’t suspect enough to go prowlin’ around.”

Jackson shuddered at the prospect. Reynolds walked down the winding path, and disappeared among the flanking oaks. But he did not go far. He suddenly remembered that the dishes out of which he had eaten were still on the kitchen table. That might cause suspicion if the law dropped in suddenly. He turned and headed swiftly back toward the house. And as he went, he heard a peculiar tingling noise he was at first unable to identify. Then he was electrified by sudden suspicion. It was such a sound as a telephone would make, if rung while a quilt or cloak was held over it to muzzle the sound from some one near at hand.

Crouching like a panther, he stole up, and looking through a crack in the door, saw Jackson standing at the phone. The man shook like a leaf and great beads of sweat stood out on his grey face. His voice was strangled and unnatural.

“Yes, yes!” he was mouthing. “I tell you, he’s here now! He’s gone down to the road, to watch for the cops. Come here as quick as you can, Leary—and come yourself. He’s bad! I’ll try to get him drunk, or asleep, or somethin’. Anyway, hurry, and for God’s sake, don’t let on I told you, even after you got him corralled.”

Reynolds threw back the door and stepped in, his face a death-mask. Jackson wheeled, saw him, and gave a choked croak. His face turned hideous; the receiver fell from his fingers and dangled at the end of its cord.

“My God, Reynolds!” he screamed. “Don’t—don’t—”

Reynolds took a single step; his gun went up and smashed down; the heavy barrel crunched against Jackson’s skull. The man went down like a slaughtered ox and lay twitching, his eyes closed, and blood oozing from a deep gash in his scalp, and from his nose and ears as well.

Reynolds stood over him an instant, snarling silently. Then he stepped to the phone and lifted the receiver. No sound came over the wire. He wondered if the man at the other end had hung up before Jackson screamed. He hung the receiver back on its hook, and strode out of the house.

A savage resentment made thinking a confused and muddled process. Jackson, the one man south of Lost Knob he had thought he could trust, had betrayed him—not for gain, not for revenge, but simply because of his cowardice. Reynolds snarled wordlessly. He was trapped; he could not reach Lost Knob in his car, and he would not have time to drive back down the Bisley road, and find another road, before the police would be racing up it. Suddenly he laughed, and it was not a good laugh to hear.

A fierce excitement galvanized him. By God, Fate had worked into his hands, after all! He did not wish to escape, only to slay before he died. Leary was one of the men he had marked for death. And Leary was coming to the Jackson farm house.

He took a step toward the corral, glanced at the sky, turned, ran back into the house, found and donned a slicker. By that time the lightning was a constant glare overhead. It was astounding—incredible. A man could almost have read a book by it. The whole northern and western sky was veined with irregular cords of blinding crimson which ran back and forth, leaping to the earth, flickering back into the heavens, crisscrossing and interlacing. Thunder rumbled, growing louder. The bank in the north west had grown appallingly. From the east around to the middle of the west it loomed, black as doom. Hills, thickets, road and buildings were bathed weirdly in the red glare as Reynolds ran to the corral where the horses whimpered fearfully. Still there was no sound in the elements but the thunder. Somewhere off in the hills a wind howled shudderingly, then ceased abruptly.

Reynolds found bridle, blanket and saddle, threw them on a restive and uneasy horse, and led it out of the corral and down behind the cliff which flanked the path that led up to the house. He tied the animal behind a thicket where it could not be seen from the path. Up in the house the oil lamp still burned. Reynolds did not bother to look to Joel Jackson. If the man ever regained consciousness at all, it would not be for many hours. Reynolds knew the effect of such a blow as he had dealt.

Minutes passed, ten—fifteen. Now he heard a sound that was not of the thunder—a distant purring that swiftly grew louder. A shaft that was not lightning stabbed the sky to the south east. It was lost, then appeared again. Reynolds knew it was an automobile topping the rises. He crouched behind a rock in a shinnery thicket close to the path, just above the point where it swung close to the rim of the low bluff.

Now he could see the headlights glinting through the trees like a pair of angry eyes. The eyes of the Law! he thought sardonically, and hugged himself with venomous glee. The car halted, then came on, marking the entering of the gate. They had not bothered to close the gate, he knew, and felt an instinctive twinge of resentment. That was typical of those Bisley laws—leave a man’s gate open, and let all his stock get out.

Now the automobile was mounting the hill, and he grew tense. Either Leary had not heard Jackson’s scream shudder over the wires, or else he was reckless. Reynolds nestled further down behind his rock. The lights swept over his head as the car came around the cliff-flanked turn. Lightning conspired to dazzle him, but as the headlights completed their arc and turned away from him, he made out the bulk of men in the car, and the glint of guns. Directly overhead thunder bellowed and a freak of lightning played full on the climbing automobile. In its brief flame he saw the car was crowded—five men, at least, and the chances were that it was Chief Leary at the wheel, though he could not be sure, in that illusive illumination.

The car picked up speed, skirting the cliff—and now Jim Reynolds thrust his .45 through the stems of the shinnery, and fired by the flare of the lightning. His shot merged with a rolling clap of thunder. The car lurched wildly as its driver, shot through the head, slumped over the wheel. Yells of terror rose as it swerved toward the cliff edge. But the man on the seat with the driver dropped his shotgun and caught frantically at the wheel.

Reynolds was standing now, firing again and again, but he could not duplicate the amazing luck of that first shot. Lead raked the car and a man yelped, but the policeman at the wheel hung on tenaciously, hindered by the corpse which slumped over it, and the car, swinging away from the bluff, roared erratically across the path, crashed through bushes and shinnery, and caromed with terrific impact against a boulder, buckling the radiator and hurling men out like tenpins.

Reynolds yelled his savage disappointment, and sent the last bullet in his gun whining viciously among the figures stirring dazedly on the ground about the smashed car. At that, their stunned minds went to work. They rolled into the brush and behind rocks. Tongues of flame began to spit at him, as they gave back his fire. He ducked down into the shinnery again. Bullets hummed over his head, or smashed against the rock in front of him, and on the heels of a belching blast there came a myriad venomous whirrings through the brush as of many bees. Somebody had salvaged a shotgun.

The wildness of the shooting told of unmanned nerves and shattered morale, but Reynolds, crouching low as he reloaded, swore at the fewness of his cartridges.

He had failed in the great coup he had planned. The car had not gone over the bluff. Four policemen still lived, and now, hiding in the thickets, they had the advantage. They could circle back and gain the house without showing themselves to his fire; they could phone for reinforcements. But he grinned fiercely as the flickering lightning showed him the body that sagged over the broken door where the impact of the collision had tossed it like a rag doll. He had not made a mistake; it was chief of police Leary who had stopped his first bullet.

The world was a hell of sound and flame; the cracking of pistols and shotguns was almost drowned in the terrific cannonade of the skies. The whole sky, when not lit by flame, was pitch black. Great sheets and ropes and chains of fire leaped terribly across the dusky vault, and the reverberations of the thunder made the earth tremble. Between the bellowings came sharp claps that almost split the ear drums. Yet not a drop of rain had fallen.

The continual glare was more confusing than utter darkness. Men shot wildly and blindly. And Reynolds began backing cautiously through the shinnery. Behind it, the ground sloped quickly, breaking off into the cliff that skirted the path further down. Down the incline Reynolds slid recklessly, and ran for his horse, half frantic on its tether. The men in the brush above yelled and blazed away vainly as they got a fleeting glimpse of him.

He ducked behind the thicket that masked the horse, tore the animal free, leaped into the saddle—and then the rain came. It did not come as it comes in less violent lands. It was as if a flood-gate had been opened on high—as if the bottom had been jerked out of a celestial rain barrel. A gulf of water descended in one appalling roar.

The wind was blowing now, roaring through the fire torn night, bending the trees, but its fury was less than the rain. Reynolds, clinging to his maddened horse, felt the beast stagger to the buffeting. Despite his slicker, the man was soaked in an instant. It was not raining in drops, but in driving sheets, in thundering cascades. His horse reeled and floundered in the torrents which were already swirling down the gulches and draws. The lightning had not ceased; it played all around him, veiled in the falling flood like fire shining through frosted glass, turning the world to frosty silver.

For a few moments he saw the light in the farm house behind him, and he tried to use it as his compass, riding directly away from it. Then it was blotted out by the shoulder of a hill, and he rode in fire-lit darkness, his sense of direction muddled and confused. He did not try to find a path, or to get back to the road, but headed straight out across the hills.

It was bitter hard going. His horse staggered in rushing rivelets, slipped on muddy slopes, blundered into trees, scratching his rider’s face and hands. In the driving rain there was no seeing any distance; the blinding lightning was a hindrance rather than a help. And the bombardment of the heavens did not cease. Reynolds rode through a hell of fire and fury, blinded, stunned and dazed by the cataclysmic war of the elements. It was nature gone mad—a saturnalia of the elements in which all sense of place and time was dimmed.

Nearby a dazzling white jet forked from the black sky with a stunning crack, and a knotted oak flew into splinters. With a shrill neigh, Reynolds’ mount bolted, blundering over rocks and through bushes. A tree limb struck Reynolds’ head, and the man fell forward over the saddle horn, dazed, keeping his seat by instinct.

It was the rain, slashing savagely in his face, that brought him to his full senses. He did not know how long he had clung to his saddle in a dazed condition, while the horse wandered at will. He wondered dully at the violence of the rain. It had not abated, though the wind was not blowing now, and the lightning had decreased much in intensity.

Grimly he gathered up the hanging reins and headed into the direction he believed was north. God, would the rain never cease? It had become a monster—an ogreish perversion of nature. It had been thundering down for hours, and still it threshed and beat, as if it poured from an inexhaustible reservoir.

He felt his horse jolt against something and stop, head drooping to the blast. The blazing sky showed him that the animal was breasting a barbed wire fence. He dismounted, fumbled for the wire clippers in the saddle pocket, cut the strands, mounted, and rode wearily on.

He topped a rise, emerged from the screening oaks and stared, blinking. At first he could not realize what he saw, it was so incongruous and alien. But he had to believe his senses. He looked on a gigantic body of water, rolling as far as he could see, lashed into foaming frenzy, under the play of the lightning.

Then the truth rushed upon him. He was looking at Bisley Lake! Bisley Lake, which that morning had been an empty basin, with its only water that which flowed along the rocky beds of Locust Creek and Mesquital, reduced by a six months’ drouth to a trickle. There in the hills, just east of where the streams merged, a dam had been built by the people of Bisley with intent to irrigate. But money had run short. The ditches had not been dug, though the dam had been completed. There lay the lake basin, ready for use, but, so far, useless. Three years would be required to fill it, the engineers said, considering average rainfall. But they were Easterners. With all their technical education they had not counted on the terrific volume of water which could rush down those postoak ridges during such a rain as had been falling. Because it was ordinarily a dry country, they had not realized that such floods could fall. From Lost Knob to Bisley the land fell at the rate of a hundred and fifty feet to every ten miles; Locust Creek and Mesquital drained a watershed of immense expanse, and were fed by myriad branches winding down from the higher ridges. Now, halted in its rush to the Gulf, this water was piling up in Bisley Lake.

Three years? It had filled in a matter of hours! Reynolds looked dazedly on the biggest body of water he had ever seen—seventy miles of waterfront, and God only knew how deep in the channels of the rivers! The rain must have assumed the proportions of a water-spout higher up on the heads of the creeks.

The rain was slackening. He knew it must be nearly dawn. Glints of daylight would be showing, but for the clouds and rain. He had been toiling through the storm for hours.

In the flare of the lightning he saw huge logs and trees whirling in the foaming wash; he saw broken buildings, and the bodies of cows, hogs, sheep, and horses, and sodden shocks of grain. He cursed to think of the havoc wrought. Fresh fury rose in him against the people of Bisley. Them and their cursed dam! Any fool ought to know it would back the water up the creeks for twenty miles and force it out of banks and over into fields and pastures. As usual, it was the hill dwellers who suffered.

He looked uneasily at the dark line of the dam. It didn’t look so big and solid as it did when the lake basin was empty, but he knew it would resist any strain. And it afforded him a bridge. The rain would cover his tracks. Wires would be down—though doubtless by this time news of his killings had been spread all over the country. Anyway, the storm would have paralyzed pursuit for a few hours. He could get back to the Lost Knob country, and into hiding.

He dismounted and led the horse out on the dam. It snorted and trembled, in fear of the water churned into foam by the drumming rain, so close beneath its feet, but he soothed it and led it on.

If God had made that gorge especially for a lake, He could not have planned it better. It was the south eastern outlet of a great basin, walled with steep hills. The gorge itself was in the shape of a gigantic V, with the narrow bottom turned toward the east, and the legs or sides of rocky cliffs, towering ninety to a hundred and fifty feet high. From the west Mesquital meandered across the broad basin, and from the north Locust Creek came down between rock ledge banks and merged with Mesquital in the wide mouth of the V. Then the river thus formed flowed through the narrow gap in the hills to the east. Across the gap the dam had been built.

Once the road to Lost Knob, climbing up from the south, had descended into that basin, crossed Mesquital and led on up into the hills to the north west. But now that road was submerged by foaming water. Directly north of the dam was no road, only a wild expanse of hills and postoak groves. But Reynolds knew he could skirt the edge of the lake and reach the old road on the other side, or better still, strike straight out through the hills, ignoring all roads and using his wire cutters to let him through fences.

His horse snorted and shied violently. Reynolds cursed and clawed at his gun, tucked under his dripping rain coat. He had just reached the other end of the dam, and something was moving in the darkness.

“Stop right where you are!” Some one was splashing toward him. The lightning revealed a man without coat or hat. His hair was plastered to his skull, and water streamed down his sodden garments. His eyes gleamed in the lightning glare.

“Bill Emmett!” exclaimed Reynolds, raising his voice above the thunder of the waters below. “What the devil you doin’ here?”

“I’m here on the devil’s business!” shouted the other. “What you doin’ here? Been to Bisley to get bail for John?”

“Bail, hell,” answered Reynolds grimly, close to the man. “I killed Saul Hopkins!”

The answer was a shriek that disconcerted him. Emmett gripped his hand and wrung it fiercely. The man seemed strung to an unnatural pitch.

“Good!” he yelled. “But they’s more in Bisley than Saul Hopkins.”

“I know,” replied Reynolds. “I aim to get some of them before I die.”

Another shriek of passionate exultation cut weirdly through the lash of the wind and the rain.

“You’re the man for me!” Emmett was fumbling with cold fingers over Reynolds’ lapels and arms. “I knowed you was the right stuff! Now you listen to me. See that water?” He pointed at the deafening torrent surging and thundering almost under their feet. “Look at it!” he screamed. “Look at it surge and foam and eddy under the lightnin’! See them whirlpools in it! Look at them dead cows and horses whirlin’ and bangin’ against the dam! Well, I’m goin’ to let that through the streets of Bisley! They’ll wake up to find the black water foamin’ through their windows! It won’t be just dead cattle floatin’ in the water! It’ll be dead men and dead women! I can see ’em now, whirlin’ down, down to the Gulf!”

Reynolds gripped the man by the shoulders and shook him savagely. “What you talkin’ about?” he roared.

A peal of wild laughter mingled with a crash of thunder. “I mean I got enough dynamite planted under this dam to split it wide open!” Emmett yelled. “I’m goin’ to send everybody in Bisley to hell before daylight!”

“You’re crazy!” snarled Reynolds, an icy hand clutching his heart.

“Crazy?” screamed the other; and the mad glare in his eyes, limned by the lightning, told Reynolds that he had spoken the grisly truth. “Crazy? You just come from killin’ that devil Hopkins, and you turn pale? You’re small stuff; you killed one enemy. I aim to kill thousands!

“Look out there where the black water is rollin’ and tumblin’. I owned that, once; leastways, I owned land the water has taken now, away over yonder. My father and grandfather owned it before me. And they condemned it and took it away from me, just because Bisley wanted a lake, damn their yellow souls!”

“The county paid you three times what the land was worth,” protested Reynolds, his peculiar sense of justice forcing him into defending an enemy.

“Yes!” Again that awful peal of laughter turned Reynolds cold. “Yes! And I put it in a Bisley bank, and the bank went broke! I lost every cent I had in the world. I’m down and out; I got no land and no money. Damn ’em, oh, damn ’em! Bisley’s goin’ to pay! I’m goin’ to wipe her out! There’s enough water out there to fill Locust Valley from ridge to ridge across Bisley. I’ve waited for this; I’ve planned for it. Tonight when I seen the lightnin’ flickerin’ over the ridges, I knew the time was come.

“I ain’t hung around here and fed the watchman corn juice for months, just for fun. He’s drunk up in his shack now, and the flood-gate’s closed! I seen to that! My charge is planted—enough to crack the dam—the water’ll do the rest. I’ve stood here all night, watchin’ Locust and Mesquital rollin’ down like the rivers of Judgment, and now it’s time, and I’m goin’ to set off the charge!”

“Emmett!” protested Reynolds, shaking with horror. “My God, you can’t do this! Think of the women and children—”

“Who thought of mine?” yelled Emmett, his voice cracking in a sob. “My wife had to live like a dog after we lost our home and money; that’s why she died. I didn’t have enough money to have her took care of. Get out of my way, Reynolds; you’re small stuff. You killed one man; I aim to kill thousands.”

“Wait!” urged Reynolds desperately. “I hate Bisley as much as anybody—but my God, man, the women and kids ain’t got nothin’ to do with it! You ain’t goin’ to do this—you can’t—” His brain reeled at the picture it evoked. Bisley lay directly in the path of the flood; its business houses stood almost on the banks of Locust Creek. The whole town was built in the bottoms; hundreds would find it impossible to escape in time to the hills, should this awful mountain of black water come roaring down the valley. Reynolds was only an anachronism, not a homicidal maniac.

In the urgency of his determination he dropped the reins of his horse and caught at Emmett. The horse snorted and galloped up the slope and away.

“Let go me, Reynolds!” howled Emmett. “I’ll kill you!”

“You’ll have to before you set off that charge!” gritted Reynolds.

Emmett screamed like a tree cat. He tore away, came on again, something glinting in his uplifted hand. Swearing, Reynolds fumbled for his gun. The hammer caught in the oilcloth. Emmett caromed against him, screaming and striking. An agonizing pain went through Reynolds’ lifted left arm, another and another; he felt the keen blade rip along his ribs, sink into his shoulder. Emmett was snarling like a wild beast, hacking blindly and madly.

They were down on the brink of the dam, clawing and smiting in the mud and water. Dimly Reynolds realized that he was being stabbed to pieces. He was a powerful man, but he was hampered by his long slicker, exhausted by his ride through the storm, and Emmett was a thing of wires of rawhide, fired by the frenzy of madness.

Reynolds abandoned his attempts to imprison Emmett’s knife wrist, and tugged again at his imprisoned gun. It came clear, just as Emmett, with a mad howl, drove his knife full into Reynolds’ breast. The madman screamed again as he felt the muzzle jam against him; then the gun thundered, so close between them it burnt the clothing of both. Reynolds was almost deafened by the report. Emmett was thrown clear of him and lay at the rim of the dam, his back broken by the tearing impact of the heavy bullet. His head hung over the edge, his arms trailed down toward the foaming black water which seemed to surge upward for him.

Reynolds essayed to rise, then sank back dizzily. Lightning played before his eyes, thunder rumbled. Beneath him the tumultuous water roared. Somewhere in the blackness there grew a hint of light. Belated dawn was stealing over the postoak hills, bent beneath a cloak of rain.

“Damn!” choked Reynolds, clawing at the mud. Incoherently he cursed; not because death was upon him, but because of the manner of his dying.

“Why couldn’t I gone out like I wanted to?—fightin’ them I hate—not a friend who’d gone bughouse. Curse the luck! And for them Bisley swine! Anyway—” the wandering voice trailed away—“died with my boots on—like a man ought to die—damn them—”

The blood-stained hands ceased to grope; the figure in the tattered slicker lay still; parting a curtain of falling rain, dawn broke grey and haggard over the postoak country.