Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

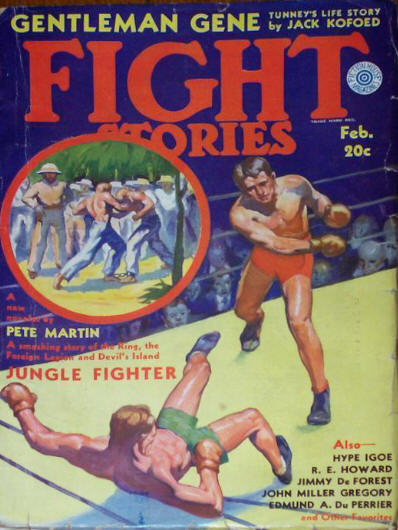

Published in Fight Stories, Vol. 4, No. 9 (February 1932).

No sooner had the Sea Girl docked in Yokohama than Mushy Hansen beat it down the waterfront to see if he couldst match me at some good fight club. Purty soon he come back and said: “No chance, Steve. You’d have to be a Scandinavian to get a scrap right now.”

“What you mean by them remarks?” I asked, suspiciously.

“Well,” said Mushy, “the sealin’ fleet’s in, and so likewise is the whalers, and the port’s swarmin’ with squareheads.”

“Well, what’s that got to do—?”

“They ain’t but one fight club on the waterfront,” said Mushy, “and it’s run by a Dutchman named Neimann. He’s been puttin’ on a series of elimination contests, and, from what I hear, he’s been cleanin’ up. He matches Swedes against Danes, see? Well, they’s hundreds of squareheads in port, and naturally each race turns out to support its countryman. So far, the Danes is ahead. You ever hear of Hakon Torkilsen?”

“You bet,” I said. “I ain’t never seen him perform, but they say he’s the real goods. Sails on the Viking, outa Copenhagen, don’t he?”

“Yeah. And the Viking’s in port. Night before last, Hakon flattened Sven Tortvigssen, the Terrible Swede, in three rounds, and tonight he takes on Dirck Jacobsen, the Gotland Giant. The Swedes and the Danes is fightin’ all over the waterfront,” said Mushy, “and they’re bettin’ their socks. I sunk a few bucks on Hakon myself. But that’s the way she stands, Steve. Nobody but Scandinavians need apply.”

“Well, heck,” I complained, “how come I got to be the victim of race prejerdice? I need dough. I’m flat broke. Wouldn’t this mug Neimann gimme a preliminary scrap? For ten dollars I’ll fight any three squareheads in port—all in the same ring.”

“Naw,” said Mushy, “they ain’t goin’ to be no preliminaries. Neimann says the crowd’ll be too impatient to set through ’em. Boy, oh boy, will they be excitement! Whichever way it goes, they’s bound to be a rough-house.”

“A purty lookout,” I said bitterly, “when the Sea Girl, the fightenest ship on the seven seas, ain’t represented in the melee. I gotta good mind to blow in and bust up the whole show—”

At this moment Bill O’Brien hove in sight, looking excited.

“Hot dawg!” he yelled. “Here’s a chance for us to clean up some dough!”

“Stand by to come about,” I advised, “and give us the lay.”

“Well,” Bill said, “I just been down along the waterfront listening to them squareheads argy—and, boy, is the money changin’ hands! I seen six fights already. Well, just now they come word that Dirck Jacobsen had broke his wrist, swinging for a sparrin’ partner and hittin’ the wall instead. So I run down to Neimann’s arena to find out if it was so, and the Dutchman was walkin’ the floor and tearin’ his hair. He said he’d pay a hundred bucks extra, win or lose, to a man good enough to go in with Torkilsen. He says if he calls the show off, these squareheads will hang him. So I see where we can run a Sea Girl man in and cop the jack!”

“And who you think we can use?” I asked skeptically.

“Well, there’s Mushy,” began Bill. “He was raised in America, of course, but—”

“Yeah, there’s Mushy!” snapped Mushy, bitterly. “You know as well as I do that I ain’t no Swede. I’m a Dane myself. Far from wantin’ to fight Hakon, I hope he knocks the block offa whatever fool Swede they finds to go against him.”

“That’s gratitude,” said Bill, scathingly. “How can a brainy man like me work up anything big when I gets opposition from all quarters? I lays awake nights studyin’ up plans for the betterment of my mates, and what do I get? Argyments! Wisecracks! Opposition! I tellya—”

“Aw, pipe down,” I said. “There’s Sven Larson—he’s a Swede.”

“That big ox would last about fifteen seconds against Hakon,” said Mushy, with gloomy satisfaction. “Besides, Sven’s in jail. He hadn’t been in port more’n a half hour when he got jugged for beatin’ up a cop.”

Bill fixed a gloomy gaze on me, and his eyes lighted.

“Hot dawg!” he whooped. “I got it! Steve, you’re a Swede!”

“Listen here, you flat-headed dogfish,” I began, in ire, “me and you ain’t had a fight in years, but by golly—”

“Aw, try to have some sense,” said Bill. “This is the idee: You ain’t never fought in Yokohama before. Neimann don’t know you, nor anybody else. We’ll pass you off for Swede—”

“Pass him off for a Swede?” gawped Mushy.

“Well,” said Bill, “I’ll admit he don’t look much like a Swede—”

“Much like a Swede!” I gnashed, my indignation mounting. “Why, you son of a—”

“Well, you don’t look nothin’ like a Swede then!” snapped Bill, disgustedly, “but we can pass you off for one. I reckon if we tell ’em you’re a Swede, they can’t prove you ain’t. If they dispute it, we’ll knock the daylights outa ’em.”

I thought it over.

“Not so bad,” I finally decided. “We’ll get that hundred extra—and, for a chance to fight somebody, I’d purtend I was a Eskimo. We’ll do it.”

“Good!” said Bill. “Can you talk Swedish?”

“Sure,” I said. “Listen: Yimmy Yackson yumped off the Yacob-ladder with his monkey-yacket on. Yimminy, what a yump!”

“Purty good,” said Bill. “Come on, we’ll go down to Neimann’s and sign up. Hey, ain’t you goin’, Mushy?”

“No, I ain’t,” said Mushy sourly. “I see right now I ain’t goin’ to enjoy this scrap none. Steve’s my shipmate but Hakon’s my countryman. Whichever loses, I won’t rejoice none. I hope it’s a draw. I ain’t even goin’ to see it.”

Well, he went off by hisself, and I said to Bill, “I gotta good mind not to go on with this, since Mushy feels that way about it.”

“Aw, he’ll get over it,” said Bill. “My gosh, Steve, this here’s a matter of business. Ain’t we all busted? Mushy’ll feel all right after we split your purse three ways and he has a few shots of hard licker.”

“Well, all right,” I said. “Let’s get down to Neimann’s.”

So me and Bill and my white bulldog, Mike, went down to Neimann’s, and, as we walked in, Bill hissed, “Don’t forget to talk Swedish.”

A short, fat man, which I reckoned was Neimann, was setting and looking over a list of names, and now and then he’d take a long pull out of a bottle, and then he’d cuss fit to curl your toes, and pull his hair.

“Well, Neimann,” said Bill, cheerfully, “what you doin’?”

“I got a list of all the Swedes in port which think they can fight,” said Neimann, bitterly. “They ain’t one of ’em would last five seconds against Torkilsen. I’ll have to call it off.”

“No you won’t,” said Bill. “Right here I got the fightin’est Swede in the Asiatics!”

Neimann faced around quick to look at me, and his eyes flared, and he jumped up like he’d been stung.

“Get outa here!” he yelped. “You should come around here and mock me in my misery! A sweet time for practical jokes—”

“Aw, cool off,” said Bill. “I tell you this Swede can lick Hakon Torkilsen with his right thumb in his mouth.”

“Swede!” snorted Neimann. “You must think I’m a prize sucker, bringin’ this black-headed mick around here and tellin’ me—”

“Mick, baloney!” said Bill. “Lookit them blue eyes—”

“I’m lookin’ at ’em,” snarled Neimann, “and thinkin’ of the lakes of Killarney all the time. Swede? Ha! Then so was Jawn L. Sullivan. So you’re a Swede, are you?”

“Sure,” I said. “Aye bane Swedish, Mister.”

“What part of Sweden?” he barked.

“Gotland,” I said, and simultaneous Bill said, “Stockholm,” and we glared at each other in mutual irritation.

“Cork, you’d better say,” sneered Neimann.

“Aye am a Swede,” I said, annoyed. “Aye want dass fight.”

“Get outa here and quit wastin’ my valuable time,” snarled Neimann. “If you’re a Swede, then I’m a Hindoo Princess!”

At this insulting insinuation I lost my temper. I despises a man that’s so suspicious he don’t trust his feller men. Grabbing Neimann by the neck with a viselike grip, and waggling a huge fist under his nose, I roared, “You insultin’ monkey! Am I a Swede or ain’t I?”

He turned pale and shook like an aspirin-leaf.

“You’re a Swede,” he agreed, weakly.

“And I get the fight?” I rumbled.

“You get it,” he agreed, wiping his brow with a bandanner. “The squareheads may stretch my neck for this, but maybe, if you keep your mouth shut, we’ll get by. What’s your name?”

“Steve—” I began, thoughtlessly, when Bill kicked me on the shin and said, “Lars Ivarson.”

“All right,” said Neimann, pessimistically, “I’ll announce it that I got a man to fight Torkilsen.”

“How much do I—how much Aye bane get?” I asked.

“I guaranteed a thousand bucks to the fighters,” he said, “to be split seven hundred to the winner and three hundred to the loser.”

“Give me das loser’s end now,” I demanded. “Aye bane go out and bet him, you betcha life.”

So he did, and said, “You better keep offa the street; some of your countrymen might ask you about the folks back home in dear old Stockholm.” And, with that, he give a bitter screech of raucous and irritating laughter, and slammed the door; and as we left, we heered him moaning like he had the bellyache.

“I don’t believe he thinks I’m a Swede,” I said, resentfully.

“Who cares?” said Bill. “We got the match. But he’s right. I’ll go place the bets. You keep outa sight. Long’s you don’t say much, we’re safe. But, if you go wanderin’ around, some squarehead’ll start talkin’ Swedish to you and we’ll be sunk.”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll get me a room at the sailor’s boardin’ house we seen down Manchu Road. I’ll stay there till it’s time for the scrap.”

So Bill went off to lay the bets, and me and Mike went down the back alleys toward the place I mentioned. As we turned out of a side street into Manchu Road, somebody come around the corner moving fast, and fell over Mike, who didn’t have time to get outa the way.

The feller scrambled up with a wrathful roar. A big blond bezark he was, and he didn’t look like a sailor. He drawed back his foot to kick Mike, as if it was the dog’s fault. But I circumvented him by the simple process of kicking him severely on the shin.

“Drop it, cull,” I growled, as he begun hopping around, howling wordlessly and holding his shin. “It wasn’t Mike’s fault, and you hadn’t no cause to kick him. Anyhow, he’d of ripped yore laig off if you’d landed—”

Instead of being pacified, he gave a bloodthirsty yell and socked me on the jaw. Seeing he was one of them bull-headed mugs you can’t reason with, I banged him once with my right, and left him setting dizzily in the gutter picking imaginary violets.

Proceeding on my way to the seamen’s boardin’s house, I forgot all about the incident. Such trifles is too common for me to spend much time thinking about. But, as it come out, I had cause to remember it.

I got me a room and stayed there with the door shut till Bill come in, jubilant, and said the crew of the Sea Girl hadst sunk all the money it could borrow at heavy odds.

“If you lose,” said he, “most of us will go back to the ship wearin’ barrels.”

“Me lose?” I snorted disgustedly. “Don’t be absurd. Where’s the Old Man?”

“Aw, I seen him down at that dive of antiquity, the Purple Cat Bar, a while ago,” said Bill. “He was purty well lit and havin’ some kind of a argyment with old Cap’n Gid Jessup. He’ll be at the fight all right. I didn’t say nothin’ to him; but he’ll be there.”

“He’ll more likely land in jail for fightin’ old Gid,” I ruminated. “They hate each other like snakes. Well, that’s his own lookout. But I’d like him to see me lick Torkilsen. I heered him braggin’ about the squarehead the other day. Seems like he seen him fight once some place.”

“Well,” said Bill, “it’s nearly time for the fight. Let’s get goin’. We’ll go down back alleys and sneak into the arena from the rear, so none of them admirin’ Swedes can get ahold of you and find out you’re really a American mick. Come on!”

So we done so, accompanied by three Swedes of the Sea Girl’s crew who was loyal to their ship and their shipmates. We snuck along alleys and slunk into the back rooms of the arena, where Neimann come in to us, perspiring freely, and told us he was having a heck of a time keeping Swedes outa the dressing-room. He said numbers of ’em wanted to come in and shake hands with Lars Ivarson before he went out to uphold the fair name of Sweden. He said Hakon was getting in the ring, and for us to hustle.

So we went up the aisle hurriedly, and the crowd was so busy cheering for Hakon that they didn’t notice us till we was in the ring. I looked out over the house, which was packed, setting and standing, and squareheads fighting to get in when they wasn’t room for no more. I never knowed they was that many Scandinavians in Eastern waters. It looked like every man in the house was a Dane, a Norwegian, or a Swede—big, blond fellers, all roaring like bulls in their excitement. It looked like a stormy night.

Neimann was walking around the ring, bowing and grinning, and every now and then his gaze wouldst fall on me as I set in my corner and he wouldst shudder viserbly and wipe his forehead with his bandanner.

Meanwhile, a big Swedish sea captain was acting the part of the announcer, and was making quite a ceremony out of it. He wouldst boom out jovially, and the crowd wouldst roar in various alien tongues, and I told one of the Swedes from the Sea Girl to translate for me, which he done so in a whisper, while pertending to tie on my gloves.

This is what the announcer was saying: “Tonight all Scandinavia is represented here in this glorious forthcoming struggle for supremacy. In my mind it brings back days of the Vikings. This is a Scandinavian spectacle for Scandinavian sailors. Every man involved in this contest is Scandinavian. You all know Hakon Torkilsen, the pride of Denmark!” Whereupon, all the Danes in the crowd bellered. “I haven’t met Lars Ivarson, but the very fact that he is a son of Sweden assures us that he will prove no mean opponent for Denmark’s favored son.” It was the Swedes’ turn to roar. “I now present the referee, Jon Yarssen, of Norway! This is a family affair. Remember, whichever way the fight goes, it will lend glory to Scandinavia!”

Then he turned and pointed toward the opposite corner and roared, “Hakon Torkilsen, of Denmark!”

Again the Danes thundered to the skies, and Bill O’Brien hissed in my ear. “Don’t forget when you’re interjuiced say ‘Dis bane happiest moment of my life!’ The accent will convince ’em you’re a Swede.”

The announcer turned toward me and, as his eyes fell on me for the first time, he started violently and blinked. Then he kind of mechanically pulled hisself together and stammered, “Lars Ivarson—of—of—Sweden!”

I riz, shedding my bathrobe, and a gasp went up from the crowd like they was thunderstruck or something. For a moment a sickening silence reigned, and then my Swedish shipmates started applauding, and some of the Swedes and Norwegians took it up, and, like people always do, got louder and louder till they was lifting the roof.

Three times I started to make my speech, and three times they drowned me out, till I run outa my short stock of patience.

“Shut up, you lubbers!” I roared, and they lapsed into sudden silence, gaping at me in amazement. With a menacing scowl, I said, “Dis bane happiest moment of my life, by thunder!”

They clapped kind of feebly and dazedly, and the referee motioned us to the center of the ring. And, as we faced each other, I gaped, and he barked, “Aha!” like a hyena which sees some critter caught in a trap. The referee was the big cheese I’d socked in the alley!

I didn’t pay much attention to Hakon, but stared morbidly at the referee, which reeled off the instructions in some Scandinavian tongue. Hakon nodded and responded in kind, and the referee glared at me and snapped something and I nodded and grunted, “Ja!” just as if I understood him, and turned back toward my corner.

He stepped after me, and caught hold of my gloves. Under cover of examining ’em he hissed, so low my handlers didn’t even hear him, “You are no Swede! I know you. You called your dog ‘Mike.’ There is only one white bulldog in the Asiatics by that name! You are Steve Costigan, of the Sea Girl.”

“Keep it quiet,” I muttered nervously.

“Ha!” he snarled. “I will have my revenge. Go ahead—fight your fight. After the bout is over, I will expose you as the imposter you are. These men will hang you to the rafters.”

“Gee whiz,” I mumbled, “what you wanta do that for? Keep my secret and I’ll slip you fifty bucks after the scrap.”

He merely snorted, “Ha!” in disdain, pointing meaningly at the black eye which I had give him, and stalked back to the center of the ring.

“What did that Norwegian say to you?” Bill O’Brien asked.

I didn’t reply. I was kinda wool-gathering. Looking out over the mob, I admit I didn’t like the prospects. I hadst no doubt that them infuriated squareheads would be maddened at the knowledge that a alien had passed hisself off as one of ’em—and they’s a limit to the numbers that even Steve Costigan can vanquish in mortal combat! But about that time the gong sounded, and I forgot everything except the battle before me.

For the first time I noticed Hakon Torkilsen, and I realized why he had such a reputation. He was a regular panther of a man—a tall, rangy, beautifully built young slugger with a mane of yellow hair and cold, steely eyes. He was six feet one to my six feet, and weighed 185 to my 190. He was trained to the ounce, and his long, smooth muscles rippled under his white skin as he moved. My black mane musta contrasted strongly with his golden hair.

He come in fast and ripped a left hook to my head, whilst I come back with a right to the body which brung him up standing. But his body muscles was like iron ridges, and I knowed it wouldst take plenty of pounding to soften him there, even though it was me doing the pounding.

Hakon was a sharpshooter, and he begunst to shoot his left straight and fast. All my opponents does, at first, thinking I’m a sucker for a left jab. But they soon abandons that form of attack. I ignores left jabs. I now walked through a perfect hail of ’em and crashed a thundering right under Hakon’s heart which brung a astonished grunt outa him. Discarding his jabbing offensive, he started flailing away with both hands, and I wanta tell you he wasn’t throwing no powder-puffs!

It was the kind of scrapping I like. He was standing up to me, giving and taking, and I wasn’t called on to run him around the ring like I gotta do with so many of my foes. He was belting me plenty, but that’s my style, and, with a wide grin, I slugged merrily at his body and head, and the gong found us in the center of the ring, banging away.

The crowd give us a roaring cheer as we went back to our corners, but suddenly my grin was wiped off by the sight of Yarssen, the referee, cryptically indicating his black eye as he glared morbidly at me.

I determined to finish Torkilsen as quick as possible, make a bold break through the crowd, and try to get away before Yarssen had time to tell ’em my fatal secret. Just as I started to tell Bill, I felt a hand jerking at my ankle. I looked down into the bewhiskered, bewildered and bleary-eyed face of the Old Man.

“Steve!” he squawked. “I’m in a terrible jam!”

Bill O’Brien jumped like he was stabbed. “Don’t yell ‘Steve’ thataway!” he hissed. “You wanta get us all mobbed?”

“I’m in a terrible jam!” wailed the Old Man, wringing his hands. “If you don’t help me, I’m a rooined man!”

“What’s the lay?” I asked in amazement, leaning through the ropes.

“It’s Gid Jessup’s fault,” he moaned. “The serpent got me into a argyment and got me drunk. He knows I ain’t got no sense when I’m soused. He hornswoggled me into laying a bet on Torkilsen. I didn’t know you was goin’ to fight—”

“Well,” I said, “that’s tough, but you’ll just have to lose the bet.”

“I can’t!” he howled.

Bong! went the gong, and I shot outa my corner as Hakon ripped outa his.

“I can’t lose!” the Old Man howled above the crowd. “I bet the Sea Girl!”

“What!” I roared, momentarily forgetting where I was, and half-turning toward the ropes. Bang! Hakon nearly tore my head off with a free-swinging right. Bellering angrily, I come back with a smash to the mush that started the claret, and we went into a slug-fest, flailing free and generous with both hands.

That Dane was tough! Smacks that would of staggered most men didn’t make him wince. He come ploughing in for more. But, just before the gong, I caught him off balance with a blazing left hook that knocked him into the ropes, and the Swedes arose, whooping like lions.

Back on my stool I peered through the ropes. The Old Man was dancing a hornpipe.

“What’s this about bettin’ the Sea Girl?” I demanded.

“When I come to myself a while ago, I found I’d wagered the ship,” he wept, “against Jessup’s lousy tub, the Nigger King, which I find is been condemned by the shippin’ board and wouldn’t clear the bay without goin’ to the bottom. He took a unfair advantage of me! I wasn’t responsible when I made that bet!”

“Don’t pay it,” I growled, “Jessup’s a rat!”

“He showed me a paper I signed while stewed,” he groaned. “It’s a contrack upholdin’ the bet. If it weren’t for that, I wouldn’t pay. But if I don’t, he’ll rooin my reputation in every port of the seven seas. He’ll show that contrack and gimme the name of a welsher. You got to lose!”

“Gee whiz!” I said, badgered beyond endurance. “This is a purty mess—”

Bong! went the gong, and I paced out into the ring, all upset and with my mind elsewhere. Hakon swarmed all over me, and drove me into the ropes, where I woke up and beat him off, but, with the Old Man’s howls echoing in my ears, I failed to follow up my advantage, and Hakon come back strong.

The Danes raised the roof as he battered me about the ring, but he wasn’t hurting me none, because I covered up, and again, just before the gong, I snapped outa my crouch and sent him back on his heels with a wicked left hook to the head.

The referee gimme a gloating look, and pointed at his black eye, and I had to grit my teeth to keep from socking him stiff. I set down on my stool and listened gloomily to the shrieks of the Old Man, which was getting more unbearable every minute.

“You got to lose!” he howled. “If Torkilsen don’t win this fight, I’m rooined! If the bet’d been on the level, I’d pay—you know that. But, I been swindled, and now I’m goin’ to get robbed! Lookit the rat over there, wavin’ that devilish paper at me! It’s more’n human flesh and blood can stand! It’s enough to drive a man to drink! You got to lose!”

“But the boys has bet their shirts on me,” I snarled, fit to be tied with worry and bewilderment. “I can’t lay down! I never throwed a fight. I don’t know how—”

“That’s gratitood!” he screamed, busting into tears. “After all I’ve did for you! Little did I know I was warmin’ a serpent in my bosom! The poorhouse is starin’ me in the face, and you—”

“Aw, shut up, you old sea horse!” said Bill. “Steve—I mean Lars—has got enough to contend with without you howlin’ and yellin’ like a maneyack. Them squareheads is gonna get suspicious if you and him keep talkin’ in English. Don’t pay no attention to him, Steve—I mean Lars. Get that Dane!”

Well, the gong sounded, and I went out all tore up in my mind and having just about lost heart in the fight. That’s a most dangerous thing to have happen, especially against a man-killing slugger like Hakon Torkilsen. Before I knowed what was goin’ on, the Swedes rose with a scream of warning and about a million stars bust in my head. I realized faintly that I was on the canvas, and I listened for the count to know how long I had to rest.

I heered a voice droning above the roar of the fans, but it was plumb meaningless to me. I shook my head, and my sight cleared. Jon Yarssen was standing over me, his arm going up and down, but I didn’t understand a word he said! He was counting in Swedish!

Not daring to risk a moment, I heaved up before my head had really quit singing an’ Hakon come storming in like a typhoon to finish me.

But I was mad clean through and had plumb forgot about the Old Man and his fool bet. I met Hakon with a left hook which nearly tore his head off, and the Swedes yelped with joy. I bored in, ripping both hands to the wind and heart, and, in a fast mix-up at close quarters, Hakon went down—more from a slip than a punch. But he was wise and took a count, resting on one knee.

I watched the referee’s arm so as to familiarize myself with the sound of the numerals—but he wasn’t counting in the same langwidge as he had over me! I got it, then; he counted over me in Swedish and over Hakon in Danish. The langwidges is alike in many ways, but different enough to get me all mixed up, which didn’t know a word in either tongue, anyhow. I seen then that I was going to have a enjoyable evening.

Hakon was up at nine—I counted the waves of the referee’s arm—and he come up at me like a house afire. I fought him off half-heartedly, whilst the Swedes shouted with amazement at the change which had come over me since that blazing first round.

Well, I’ve said repeatedly that a man can’t fight his best when he’s got his mind on something else. Here was a nice mess for me to worry about. If I quit, I’d be a yeller dog and despize myself for the rest of my life, and my shipmates would lose their money, and so would all the Swedes which had bet on me and was now yelling and cheering for me just like I was their brother. I couldn’t throw ’em down. Yet if I won, the Old Man would lose his ship, which was all he had and like a daughter to him. It wouldst beggar him and break his heart. And, as a minor thought, whether I won or lost, that scut Yarssen was going to tell the crowd I wasn’t no Swede, and get me mobbed. Every time I looked at him over Hakon’s shoulder in a clinch, Yarssen wouldst touch his black eye meaningly. I was bogged down in gloom, and I wished I could evaporate or something.

Back on my stool, between rounds, the Old Man wept and begged me to lay down, and Bill and my handlers implored me to wake up and kill Torkilsen, and I thought I’d go nuts.

I went out for the fourth round slowly, and Hakon, evidently thinking I’d lost my fighting heart, if any, come with his usual tigerish rush and biffed me three times in the face without a return.

I dragged him into a grizzly-like clinch which he couldn’t break, and as we rassled and strained, he spat something at me which I couldn’t understand, but I understood the tone of it. He was calling me yellow! Me, Steve Costigan, the terror of the high seas!

With a maddened roar, I jerked away from him and crashed a murderous right to his jaw that nearly floored him. Before he couldst recover his balance, I tore into him like a wild man, forgetting everything except that I was Steve Costigan, the bully of the toughest ship afloat.

Slugging right and left, I rushed him into the ropes, where I pinned him, while the crowd went crazy. He crouched and covered up, taking most of my punches on the gloves and elbows, but I reckoned it looked to the mob like I was beating him to death. All at once, above the roar, I heered the Old Man screaming, “Steve, for cats’ sake, let up! I’ll go on the beach, and it’ll be your fault!”

That unnerved me. I involuntarily dropped my hands and recoiled, and Hakon, with fire in his eyes, lunged outa his crouch like a tiger and crashed his right to my jaw.

Bang! I was on the canvas again, and the referee was droning Swedish numerals over me. Not daring to take a count, and maybe get counted out unknowingly, I staggered up, and Hakon come lashing in. I throwed my arms around him in a grizzly hug, and it took him and the referee both to break my hold.

Hakon drove me staggering into the ropes with a wild-man attack, but I’m always dangerous on the ropes, as many a good man has found out on coming to in his dressing room. As I felt the rough strands against my back, I caught him with a slung-shot right uppercut which snapped his head right back betwixt his shoulders, and this time it was him which fell into a clinch and hung on.

Looking over his shoulder at that sea of bristling blond heads and yelling faces, I seen various familiar figgers. On one side of the ring—near my corner—the Old Man was dancing around like he was on a red-hot hatch, shedding maudlin tears and pulling his whiskers; and, on the other side, a skinny, shifty-eyed old seaman was whooping with glee and waving a folded paper. Cap’n Gid Jessup, the old cuss! He knowed the Old Man would bet anything when he was drunk—even bet the Sea Girl, as sweet a ship as ever rounded the Horn, against that rotten old hulk of a Nigger King, which wasn’t worth a cent a ton. And, near at hand, the referee, Yarssen, was whispering tenderly in my ear, as he broke our clinch, “Better let Hakon knock you stiff—then you won’t feel so much what the crowd does to you when I tell them who you are!”

Back on my stool again, I put my face on Mike’s neck and refused to listen either to the pleas of the Old Man or to the profane shrieks of Bill O’Brien. By golly, that fight was like a nightmare! I almost hoped Hakon would knock my brains out and end all my troubles.

I went out for the fifth like a man going to his own hanging. Hakon was evidently puzzled. Who wouldn’t of been? Here was a fighter—me—who was performing in spurts, exploding in bursts of ferocious battling just when he appeared nearly out, and sagging half heartedly when he looked like a winner.

He come in, lashed a vicious left to my mid-section, and dashed me to the canvas with a thundering overhand right. Maddened, I arose and dropped him with a wild round-house swing he wasn’t expecting. Again the crowd surged to its feet, and the referee got flustered and started counting over Hakon in what sounded like Swedish.

Hakon bounded up and slugged me into the ropes, offa which I floundered, only to slip in a smear of my own blood on the canvas, and again, to the disgust of the Swedes, I found myself among the resin.

I looked about, heard the Old Man yelling for me to stay down, and saw Old Cap’n Jessup waving his blame-fool contrack. I arose, only half aware of what I was doing, and bang! Hakon caught me on the ear with a hurricane swing, and I sprawled on the floor, half under the ropes.

Goggling dizzily at the crowd from this position, I found myself staring into the distended eyes of Cap’n Gid Jessup, which was standing up, almost touching the ring. Evidently froze at the thought of losing his bet—with me on the canvas—he was standing there gaping, his arm still lifted with the contrack which he’d been waving at the Old Man.

With me, thinking is acting. One swoop of my gloved paw swept that contrack outa his hand. He yawped with suprise and come lunging half through the ropes. I rolled away from him, sticking the contrack in my mouth and chawing as fast as I could. Cap’n Jessup grabbed me by the hair with one hand and tried to jerk the contrack outa my jaws with the other’n, but all he got was a severely bit finger.

At this, he let go of me and begun to scream and yell. “Gimme back that paper, you cannibal! He’s eatin’ my contrack! I’ll sue you—!”

Meanwhile, the dumbfounded referee, overcome with amazement, had stopped counting, and the crowd, not understanding this by-play, was roaring with astonishment. Jessup begun to crawl through the ropes, and Yarssen yelled something and shoved him back with his foot. He started through again, yelling blue murder, and a big Swede, evidently thinking he was trying to attack me, swung once with a fist the size of a caulking mallet, and Cap’n Jessup bit the dust.

I arose with my mouth full of paper, and Hakon promptly banged me on the chin with a right he started from his heels. Ow, Jerusha! Wait’ll somebody hits you on the jaw when you’re chawing something! I thought for a second every tooth in my head was shattered, along with my jaw-bone. But I reeled groggily back into the ropes and begun to swaller hurriedly.

Bang! Hakon whanged me on the ear. “Gulp!” I said. Wham! He socked me in the eye. “Gullup!” I said. Blop! He pasted me in the stummick. “Oof—glup!” I said. Whang! He took me on the side of the head. “Gulp!” I swallered the last of the contrack, and went for that Dane with fire in my eyes.

I banged Hakon with a left that sunk outa sight in his belly, and nearly tore his head off with a paralyzing right before he realized that, instead of being ready for the cleaners, I was stronger’n ever and ra’ring for action.

Nothing loath, he rallied, and we went into a whirlwind of hooks and swings till the world spun like a merry-go-round. Neither of us heered the gong, and our seconds had to drag us apart and lead us to our corners.

“Steve,” the Old Man was jerking at my leg and weeping with gratitude, “I seen it all! That old pole-cat’s got no hold on me now. He can’t prove I ever made that fool bet. You’re a scholar and a gent—one of nature’s own noblemen! You’ve saved the Sea Girl!”

“Let that be a lesson to you,” I said, spitting out a fragment of the contrack along with a mouthful of blood. “Gamblin’ is sinful. Bill, I got a watch in my pants pocket. Get it and bet it that I lay this squarehead within three more rounds.”

And I come out for the sixth like a typhoon. “I’m going to get mobbed by the fans as soon as the fight’s over and Yarssen spills the beans,” I thought, “but I’ll have my fun now.”

For once I’d met a man which was willing and able to stand up and slug it out with me. Hakon was as lithe as a panther and as tough as spring-steel. He was quicker’n me, and hit nearly as hard. We crashed together in the center of the ring, throwing all we had into the storm of battle.

Through a red mist I seen Hakon’s eyes blazing with a unearthly light. He was plumb berserk, like them old Vikings which was his ancestors. And all the Irish fighting madness took hold of me, and we ripped and tore like tigers.

We was the center of a frenzied whirlwind of gloves, ripping smashes to each other’s bodies which you could hear all over the house, and socks to each other’s heads that spattered blood all over the ring. Every blow packed dynamite and had the killer’s lust behind it. It was a test of endurance.

At the gong, we had to be tore apart and dragged to our corners by force, and, at the beginning of the next round, we started in where we’d left off. We reeled in a blinding hurricane of gloves. We slipped in smears of blood, or was knocked to the canvas by each other’s thundering blows.

The crowd was limp and idiotic, drooling wordless screeches. And the referee was bewildered and muddled. He counted over us in Swedish, Danish and Norwegian alike. Then I was on the canvas, and Hakon was staggering on the ropes, gasping, and the befuddled Yarssen was counting over me. And, in the dizzy maze, I recognized the langwidge. He was counting in Spanish!

“You ain’t no Norwegian!“ I said, glaring groggily up at him.

“Four!” he said, shifting into English. “—As much as you’re a Swede! Five! A man’s got to eat. Six! They wouldn’t have given me this job—seven!—if I hadn’t pretended to be a Norwegian. Eight! I’m John Jones, a vaudeville linguist from Frisco. Nine! Keep my secret and I’ll keep yours.”

The gong! Our handlers dragged us off to our corners and worked over us. I looked over at Hakon. I was marked plenty—a split ear, smashed lips, both eyes half closed, nose broken—but them’s my usual adornments. Hakon wasn’t marked up so much in the face—outside of a closed eye and a few gashes—but his body was raw beef from my continuous body hammering. I drawed a deep breath and grinned gargoylishly. With the Old Man and that fake referee offa my mind, I couldst give all my thoughts to the battle.

The gong banged again, and I charged like a enraged bull. Hakon met me as usual, and rocked me with thundering lefts and rights. But I bored in, driving him steadily before me with ripping, bone-shattering hooks to the body and head. I felt him slowing up. The man don’t live which can slug with me!

Like a tiger scenting the kill, I redoubled the fury of my onslaught, and the crowd arose, roaring, as they foresaw the end. Nearly on the ropes, Hakon rallied with a dying burst of ferocity, and momentarily had me reeling under a fusillade of desperate swings. But I shook my head doggedly and plowed in under his barrage, ripping my terrible right under his heart again and again, and tearing at his head with mallet-like left hooks.

Flesh and blood couldn’t stand it. Hakon crumpled in a neutral corner under a blasting fire of left and right hooks. He tried to get his legs under him, but a child couldst see he was done.

The referee hesitated, then raised my right glove, and the Swedes and Norwegians came roaring into the ring and swept me offa my feet. A glance showed Hakon’s Danes carrying him to his corner, and I tried to get to him to shake his hand, and tell him he was as brave and fine a fighter as I ever met—which was the truth and nothing else—but my delirious followers hadst boosted both me and Mike on their shoulders and were carrying us toward the dressing-room like a king or something.

A tall form come surging through the crowd, and Mushy Hansen grabbed my gloved hand and yelled, “Boy, you done us proud! I’m sorry the Danes had to lose, but, after a battle like that, I can’t hold no grudge. I couldn’t stay away from the scrap. Hooray for the old Sea Girl, the fightin’est ship on the seven seas!”

And the Swedish captain, which had acted as announcer, barged in front of me and yelled in English, “You may be a Swede, but if you are, you’re the most unusual looking Swede I ever saw. But I don’t give a whoop! I’ve just seen the greatest battle since Gustavus Adolphus licked the Dutch! Skoal, Lars Ivarson!”

And all the Swedes and Norwegians thundered, “Skoal, Lars Iverson!”

“They want you to make a speech,” said Mushy.

“All right,” I said. “Dis bane happiest moment of my life!”

“Louder,” said Mushy. “They’re makin’ so much noise they can’t understand you, anyhow. Say somethin’ in a foreign langwidge.”

“All right,” I said, and yelled the only foreign words I couldst think of, “Parleyvoo Francais! Vive le Stockholm! Erin go bragh!”

And they bellered louder’n ever. A fighting man is a fighting man in any langwidge!