Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

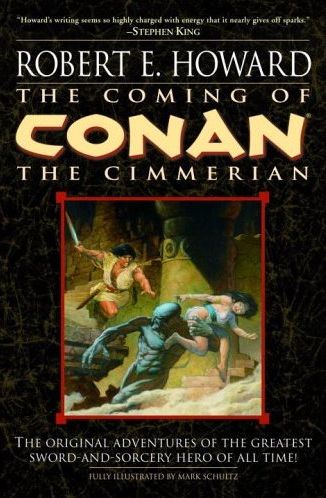

Published in Magazine of Horror, No. 15 (Spring 1967)

though this is taken from the collection The Coming of Conan The Cimmerian, 2003.

| I | II | III |

The thunder of the drums and the great elephant tusk horns was deafening, but in Livia’s ears the clamor seemed but a confused muttering, dull and far away. As she lay on the angareb in the great hut, her state bordered between delirium and semi-unconsciousness. Outward sounds and movements scarcely impinged upon her senses. Her whole mental vision, though dazed and chaotic, was yet centered with hideous certitude on the naked, writhing figure of her brother, blood streaming down the quivering thighs. Against a dim nightmare background of dusky interweaving shapes and shadows, that white form was limned in merciless and awful clarity. The air seemed still to pulsate with an agonized screaming, mingled and interwoven obscenely with a rustle of fiendish laughter.

She was not conscious of sensation as an individual, separate and distinct from the rest of the cosmos. She was drowned in a great gulf of pain—was herself but pain crystallized and manifested in flesh. So she lay without conscious thought or motion, while outside the drums bellowed, the horns clamored, and barbaric voices lifted hideous chants, keeping time to naked feet slapping the hard earth and open palms smiting one another softly.

But through her frozen mentality individual consciousness at last began slowly to seep. A dull wonder that she was still bodily unharmed first made itself manifest. She accepted the miracle without thanksgiving. The matter seemed meaningless. Acting mechanically, she sat up on the angareb and stared dully about her. Her extremities made feeble beginnings of motions, as if responding to blindly awakening nerve-centers. Her naked feet scruffed nervously at the hard-beaten dirt floor. Her fingers twitched convulsively at the skirt of the scanty under-tunic which constituted her only garment. Impersonally she remembered that once, it seemed long, long ago, rude hands had torn her other garments from her body, and she had wept with fright and shame. It seemed strange, now, that so small a wrong should have caused her so much woe. The magnitude of outrage and indignity was only relative, after all, like everything else.

The hut door opened, and a black woman entered—a lithe pantherish creature, whose supple body gleamed like polished ebony, adorned only by a wisp of silk twisted about her strutting loins. The whites of her eyeballs reflected the firelight outside, as she rolled them with wicked meaning.

She bore a bamboo dish of food—smoking meat, roasted yams, mealies, unwieldy ingots of native bread—and a vessel of hammered gold, filled with yarati beer. These she set down on the angareb, but Livia paid no heed; she sat staring dully at the opposite wall, hung with mats woven of bamboo shoots. The young black woman laughed evilly, with a flash of dark eyes and white teeth, and with a hiss of spiteful obscenity and a mocking caress that was more gross than her language, she turned and swaggered out of the hut, expressing more taunting insolence with the motions of her hips than any civilized woman could with spoken insults.

Neither the wench’s words nor her actions had stirred the surface of Livia’s consciousness. All her sensations were still turned inward. Still the vividness of her mental pictures made the visible world seem like an unreal panorama of ghosts and shadows. Mechanically she ate the food and drank the liquor without tasting either.

It was still mechanically that at last she rose and walked unsteadily across the hut, to peer out through a crack between the bamboos. It was an abrupt change in the timbre of the drums and horns that reacted upon some obscure part of her mind and made her seek the cause, without sensible volition.

At first she could make out nothing of what she saw; all was chaotic and shadowy, shapes moving and mingling, writhing and twisting, black formless blocks hewed out starkly against a setting of blood-red that dulled and glowed. Then actions and objects assumed their proper proportions, and she made out men and women moving about the fires. The red light glinted on silver and ivory ornaments; white plumes nodded against the glare; naked black figures strutted and posed, silhouettes carved out of darkness and limned in crimson.

On an ivory stool, flanked by giants in plumed head-pieces and leopard-skin girdles, sat a fat, squat shape, abysmal, repulsive, a toad-like chunk of blackness, reeking of the dank rotting jungle and the nighted swamps. The creature’s pudgy hands rested on the sleek arch of his belly; his nape was a roll of sooty fat that seemed to thrust his bullet head forward. His eyes gleamed in the firelight, like live coals in a dead black stump. Their appalling vitality belied the inert suggestion of the gross body.

As the girl’s gaze rested on that repellant figure, her body stiffened and tensed as frantic Life surged through her again. From a mindless automaton, she changed suddenly to a sentient mold of live, quivering flesh, stinging and burning. Pain was drowned in hate, so intense it in turn became pain; she felt hard and brittle, as if her body were turning to steel. She felt her hate flow almost tangibly out along the line of her vision; so it seemed to her that the object of her emotion should fall dead from his carven stool because of its force.

But if Bajujh, king of Bakalah, felt any psychic discomfort because of the concentration of his captive, he did not show it. He continued to cram his frog-like mouth to capacity with handfuls of mealies scooped up from a vessel held up to him by a kneeling woman, and to stare down a broad lane which was being formed by the action of his subjects in pressing back on either hand.

Down this lane, walled with sweaty black humanity, Livia vaguely realized some important personage would come, judging from the strident clamor of drum and horn. And as she watched, one came.

A column of fighting men, marching three abreast, advanced toward the ivory stool, a thick line of waving plumes and glinting spears meandering through the motley crowd. At the head of the ebon spearmen strode a figure at the sight of which Livia started violently; her heart seemed to stop, then began to pound again, suffocatingly. Against that dusky background, this man stood out with vivid distinctness. He was clad like his followers in leopard-skin loin-clout and plumed head-piece, but he was a white man.

It was not in the manner of a suppliant or a subordinate that he strode up to the ivory stool, and sudden silence fell over the throng as he halted before the squatting figure. Livia felt the tenseness, though she only dimly knew what it portended. For a moment Bajujh sat, craning his short neck upward, like a great frog; then, as if pulled against his will by the other’s steady glare, he shambled up off his stool, and stood grotesquely bobbing his shaven head.

Instantly the tension was broken. A tremendous shout went up from the massed villagers, and at a gesture from the stranger, his warriors lifted their spears and boomed a salute royale for King Bajujh. Whoever he was, Livia knew the man must indeed be powerful in that wild land, if Bajujh of Bakalah rose to greet him. And power meant military prestige—violence was the only thing respected by those ferocious races.

Thereafter Livia stood with her eyes glued to the crack in the hut wall, watching the white stranger. His warriors mingled with the Bakalas, dancing, feasting, swigging beer. He himself, with a few of his chiefs, sat with Bajujh and the headmen of Bakalah, cross-legged on mats, gorging and guzzling. She saw his hands dipped deep into the cooking pots with the others, saw his muzzle thrust into the beer vessel out of which Bajujh also drank. But she noticed, nevertheless, that he was accorded the respect due a king. Since he had no stool, Bajujh renounced his also, and sat on the mats with his guest. When a new pot of beer was brought, the king of Bakalah barely sipped it before he passed it to the white man. Power! All this ceremonial courtesy pointed to power—strength—prestige! Livia trembled in excitement as a breathless plan began to form in her mind.

So she watched the white man with painful intensity, noting every detail of his appearance. He was tall; neither in height nor in massiveness was he exceeded by many of the giant blacks. He moved with the lithe suppleness of a great panther. When the firelight caught his eyes, they burned like blue fire. High-strapped sandals guarded his feet, and from his broad girdle hung a sword in a leather scabbard. His appearance was alien and unfamiliar; Livia had never seen his like. But she made no effort to classify his position among the races of mankind. It was enough that his skin was white.

The hours passed, and gradually the roar of revelry lessened, as men and women sank into drunken sleep. At last Bajujh rose tottering, and lifted his hands, less a sign to end the feast, than a token of surrender in the contest of gorging and guzzling, and stumbling, was caught by his warriors who bore him to his hut. The white man rose, apparently none the worse for the incredible amount of beer he had quaffed, and was escorted to the guest hut by such of the Bakala headmen as were able to reel along. He disappeared into the hut, and Livia noticed that a dozen of his own spearmen took their places about the structure, spears ready. Evidently the stranger was taking no chances on Bajujh’s friendship.

Livia cast her glance about the village, which faintly resembled a dusky Night of Judgment, what with the straggling streets strewn with drunken shapes. She knew that men in full possession of their faculties guarded the outer boma, but the only wakeful men she saw inside the village were the spearmen about the white man’s hut—and some of these were beginning to nod and lean on their spears.

With her heart beating hammer-like, she glided to the back of her prison hut and out the door, passing the snoring guard Bajujh had set over her. Like an ivory shadow she glided across the space between her hut and that occupied by the stranger. On her hands and knees she crawled up to the back of that hut. A black giant squatted here, his plumed head sunk on his knees. She wriggled past him to the wall of the hut. She had first been imprisoned in that hut, and a narrow aperture in the wall, hidden inside by a hanging mat, represented her weak and pathetic attempt at escape. She found the opening, turned sidewise and wriggled her lithe body through, thrusting the inner mat aside.

Firelight from without faintly illumined the interior of the hut. Even as she thrust back the mat, she heard a muttered curse, felt a vise-like grasp in her hair, and was dragged bodily through the aperture and plumped down on her feet.

Staggering with the suddenness of it, she gathered her scattered wits together, and raked her disordered tresses out of her eyes, to stare up into the face of the white man who towered over her, amazement written on his dark scarred face. His sword was naked in his hand, and his eyes blazed like bale-fire, whether with anger, suspicion or surprize she could not judge. He spoke in a language she could not understand—a tongue which was not a negro guttural, yet did not have a civilized sound.

“Oh, please!” she begged. “Not so loud. They will hear—”

“Who are you?” he demanded, speaking Ophirean with a barbarous accent. “By Crom, I never thought to find a white girl in this hellish land!”

“My name is Livia,” she answered. “I am Bajujh’s captive. Oh, listen, please listen to me! I can not stay here long. I must return before they miss me from my hut.

“My brother—” a sob choked her, then she continued: “My brother was Theteles, and we were of the house of Chelkus, scientists and noblemen of Ophir. By special permission of the king of Stygia, my brother was allowed to go to Kheshatta, the city of magicians, to study their arts, and I accompanied him. He was only a boy—younger than myself—” her voice faltered and broke. The stranger said nothing, but stood watching her with burning eyes, his face frowning and unreadable. There was something wild and untamable about him that frightened her and made her nervous and uncertain.

“The black Kushites raided Kheshatta,” she continued hurriedly. “We were approaching the city in a camel caravan. Our guards fled and the raiders carried us away with them. But they did us no harm, and let us know that they would parley with the Stygians and accept a ransom for our return. But one of the chiefs desired all the ransom for himself, and he and his followers stole us out of the camp one night, and fled far to the south-east with us, to the very borders of Kush. There they were attacked and cut down by a band of Bakala raiders. Theteles and I were dragged into this den of beasts—” she sobbed convulsively. “—This morning my brother was mutilated and butchered before me—” She gagged and went momentarily blind at the memory. “They fed his body to the jackals. How long I lay in a faint I do not know—”

Words failing her, she lifted her eyes to the scowling face of the stranger. A mad fury swept over her; she lifted her fists and beat futilely on his mighty breast, which he heeded no more than the buzzing of a fly.

“How can you stand there like a dumb brute?” she screamed in a ghastly whisper. “Are you but a beast like these others? Ah, Mitra, once I thought there was honor in men. Now I know each has his price. You—what do you know of honor—or of mercy or decency? You are a barbarian like these others—only your skin is white, your soul is black as theirs.

“You care naught that a man of your own color has been foully done to death by these black dogs—that a white woman is their slave! Very well!” She fell back from him, panting, transfigured by her passion.

“I will give you a price!” she raved, tearing away her tunic from her ivory breasts. “Am I not fair? Am I not more desirable than these soot-colored wenches? Am I not a worthy reward for blood-letting? Is not a fair-skinned virgin a price worth slaying for?

“Kill that black dog Bajujh! Let me see his cursed head roll in the bloody dust! Kill him! Kill him!” She beat her clenched fists together in the agony of her intensity. “Then take me and do as you wish with me. I will be your slave!”

He did not speak for an instant, but stood like a giant brooding figure of slaughter and destruction, fingering his hilt.

“You speak as if you were free to give yourself at your pleasure,” he said. “As if the gift of your body had power to swing kingdoms. Why should I kill Bajujh to obtain you? Women are cheap as plantains in this land, and their willingness or unwillingness matters as little. You value yourself too highly. If I wanted you, I wouldn’t have to fight Bajujh to take you. He would rather give you to me than to fight me.”

Livia gasped. All the fire went out of her, the hut reeled dizzily before her eyes. She staggered and sank in a crumpled heap on an angareb. Dazed bitterness crushed her soul as the realization of her utter helplessness was thrust brutally upon her. The human mind clings unconsciously to familiar values and ideas, even among surroundings and conditions alien and unrelated to those environs to which such values and ideas are adapted. In spite of all Livia had experienced, she had still instinctively supposed a woman’s consent the pivot point of such a game as she proposed to play. She was stunned by the realization that nothing hinged upon her at all. She could not move men as pawns in a game; she herself was the helpless pawn.

“I see the absurdity of supposing that any man in this corner of the world would act according to rules and customs existent in another corner of the planet,” she murmured weakly, scarcely conscious of what she was saying, which was indeed only the vocal framing of the thought which overcame her. Stunned by that newest twist of fate, she lay motionless, until the white barbarian’s iron fingers closed on her shoulder and lifted her again to her feet.

“You said I was a barbarian,” he said harshly, “and that is true, Crom be thanked. If you had had men of the outlands guarding you instead of soft-gutted civilized weaklings, you would not be the slave of a black pig this night. I am Conan, a Cimmerian, and I live by the sword’s edge. But I am not such a dog as to leave a white woman in the clutches of a black man; and though your kind call me a robber, I never forced a woman against her consent. Customs differ in various countries, but if a man is strong enough, he can enforce a few of his native customs anywhere. And no man ever called me a weakling!

“If you were old and ugly as the devil’s pet vulture, I’d take you away from Bajujh, simply because of the color of your hide.

“But you are young and beautiful, and I have looked at black sluts until I am sick at the guts. I’ll play this game your way, simply because some of your instincts correspond with some of mine. Get back to your hut. Bajujh’s too drunk to come to you tonight, and I’ll see that he’s occupied tomorrow. And tomorrow night it will be Conan’s bed you’ll warm, not Bajujh’s.”

“How will it be accomplished?” She was trembling with mingled emotions. “Are these all your warriors?”

“They’re enough,” he grunted. “Bamulas, every one of them, and suckled at the teats of war. I came here at Bajujh’s request. He wants me to join him in an attack on Jihiji. Tonight we feasted. Tomorrow we hold council. When I get through with him, he’ll be holding council in Hell.”

“You will break the truce?”

“Truces in this land are made to be broken,” he answered grimly. “He would break his truce with Jihiji. And after we’d looted the town together, he’d wipe me out the first time he caught me off guard. What would be blackest treachery in another land, is wisdom here. I have not fought my way alone to the position of war-chief of the Bamulas without learning all the lessons the black country teaches. Now go back to your hut and sleep, knowing that it is not for Bajujh but for Conan that you preserve your beauty!”

Through the crack in the bamboo wall, Livia watched, her nerves taut and trembling. All day, since their late waking, bleary and sodden, from their debauch of the night before, the black people had prepared the feast for the coming night. All day Conan the Cimmerian had sat in the hut of Bajujh, and what had passed between them, Livia could not know. She had fought to hide her excitement from the only person who entered her hut—the vindictive black girl who brought her food and drink. But that ribald wench had been too groggy from her libations of the previous night to notice the change in her captive’s demeanor.

Now night had fallen again, fires lighted the village, and once more the chiefs left the king’s hut and squatted down in the open space between the huts to feast and hold a final, ceremonious council. This time there was not so much beer-guzzling. Livia noticed the Bamulas casually converging toward the circle where sat the chief men. She saw Bajujh, and sitting opposite him across the eating-pots, Conan, laughing and conversing with the giant Aja, Bajujh’s war-chief.

The Cimmerian was gnawing a great beef-bone, and as she watched, she saw him cast a glance across his shoulder. As if it were a signal for which they had been waiting, the Bamulas all turned their gaze toward their chief. Conan rose, still smiling, as if to reach into a near-by cooking pot—then quick as a cat he struck Aja a terrible blow with the heavy bone. The Bakala war-chief slumped over, his skull crushed in, and instantly a frightful yell rent the skies as the Bamulas went into action like blood-mad panthers.

Cooking-pots overturned, scalding the squatting women, bamboo walls buckled to the impact of plunging bodies, screams of agony ripped the night, and over all rose the exultant “Yee! yee! yee!” of the maddened Bamulas, the flame of spears that crimsoned in the lurid glow.

Bakalah was a madhouse that reddened into a shambles. The action of the invaders paralyzed the luckless villagers by its unexpected suddenness. No thought of attack by their guests had ever entered their woolly pates. Most of the spears were stacked in the huts, many of the warriors already half-drunk. The fall of Aja was a signal that plunged the gleaming blades of the Bamulas into a hundred unsuspecting bodies; after that it was massacre.

At her peep-hole Livia stood frozen, white as a statue, her golden locks drawn back and grasped in a knotted cluster with both hands at her temples. Her eyes were dilated, her whole body rigid. The yells of pain and fury smote her tortured nerves like a physical impact; the writhing, slashing forms blurred before her, then sprang out again with horrifying distinctness. She saw spears sink into writhing black bodies, spilling red. She saw clubs swing and descend with brutal force on kinky heads. Brands were kicked out of the fires, scattering sparks; hut-thatches smoldered and blazed up. A fresh stridency of anguish cut through the cries, as living victims were hurled headfirst into the blazing structures. The scent of scorched flesh began to sicken the air, already rank with reeking sweat and fresh blood.

Livia’s overwrought nerves gave way. She cried out again and again, shrill screams of torment, lost in the roar of flames and slaughter. She beat her temples with her clenched fists. Her reason tottered, changing her cries to more awful peals of hysterical laughter. In vain she sought to keep before her the fact that it was her enemies who were dying thus horribly—that this was as she had madly hoped and plotted—that this ghastly sacrifice was but a just repayment for the wrongs done her and hers. Frantic terror held her in its unreasoning grasp.

She was aware of no pity for the victims who were dying wholesale under the dripping spears. Her only emotion was blind, stark, mad, unreasoning fear. She saw Conan, his white form contrasting with the blacks. She saw his sword flash, and men went down around him. Now a struggling knot swept around a fire, and she glimpsed a fat squat shape writhing in its midst. Conan ploughed through and was hidden from view by the twisting black figures. From the midst a thin squealing rose unbearably. The press split for an instant, and she had one awful glimpse of a reeling desperate squat figure, streaming blood. Then the throng crowded in again, and steel flashed in the mob like a beam of lightning through the dusk.

A beast-like baying rose, terrifying in its primitive exultation. Through the mob Conan’s tall form pushed its way. He was striding toward the hut where the girl cowered, and in his hand he bore a ghastly relic—the firelight gleamed redly on King Bajujh’s severed head. The black eyes, glassy now instead of vital, rolled up, revealing only the whites; the jaw hung slack as if in a grin of idiocy; red drops showered thickly along the ground.

Livia gave back with a moaning cry. Conan had paid the price, and was coming to claim her, bearing the awful token of his payment. He would grasp her with his hot bloody fingers, crush her lips with mouth still panting from the slaughter. With the thought came delirium.

With a scream Livia ran across the hut, threw herself against the door in the back wall. It fell open, and she darted across the open space, a flitting white ghost in a realm of black shadows and red flame.

Some obscure instinct led her to the pen where the horses were kept. A warrior was just taking down the bars that separated the horse-pen from the main boma, and he yelled in amazement as she darted past him. His dusky hand clutched at her, closed on the neck of her tunic. With a frantic jerk she tore away, leaving the garment in his hand. The horses snorted and stampeded past her, rolling the black man in the dust—lean, wiry steeds of the Kushite breed, already frantic with the fire and the scent of blood.

Blindly she caught at a flying mane, was jerked off her feet, struck the ground again on her toes, sprang high, pulled and scrambled herself upon the horse’s straining back. Mad with fear the herd plunged through the fires, their small hoofs knocking sparks in a blinding shower. The startled black people had a wild glimpse of the girl clinging naked to the mane of a beast that raced like the wind that streamed out his rider’s loose yellow hair. Then straight for the boma the steed bolted, soared breath-takingly into the air, and was gone into the night.

Livia could make no attempt to guide her steed, nor did she feel any need of so doing. The yells and the glow of the fires were fading out behind her; the wind tossed her hair and caressed her naked limbs. She was aware only of a dazed need to hold to the flowing mane and ride, ride, ride over the rim of the world and away from all agony and grief and horror.

And for hours the wiry steed raced, until, topping a star-lit crest, he stumbled and hurled his rider headlong.

She struck on soft cushioning sward, and lay for an instant half stunned, dimly hearing her mount trot away. When she staggered up, the first thing that impressed her was the silence. It was an almost tangible thing, soft, darkly velvet, after the incessant blare of barbaric horns and drums which had maddened her for days. She stared up at the great white stars clustered thickly in the dark blue sky. There was no moon, yet the starlight illuminated the land, though illusively, with unexpected clusterings of shadow. She stood on a swarded eminence from which the gently molded slopes ran away, soft as velvet under the starlight. Far away in one direction she discerned a dense dark line of trees which marked the distant forest. Here there was only night and trancelike stillness and a faint breeze blowing through the stars.

The land seemed vast and slumbering. The warm caress of the breeze made her aware of her nakedness and she wriggled uneasily, spreading her hands over her body. Then she felt the loneliness of the night, and the unbrokenness of the solitude. She was alone; she stood naked on the summit of the land and there was none to see; nothing but night and the whispering wind.

She was suddenly glad of the night and the loneliness. There was none to threaten her, or to seize her with rude violent hands. She looked before her and saw the slope falling away into a broad valley; there fronds waved thickly and the starlight reflected whitely on many small objects scattered throughout the vale. She thought they were great white blossoms, and the thought gave rise to vague memory; she thought of a valley of which the blacks had spoken with fear; a valley to which had fled the young women of a strange brown-skinned race which had inhabited the land before the coming of the ancestors of the Bakalas. There, men said, they had turned into white flowers, had been transformed by the old gods to escape their ravishers. There no black man dared go.

But into that valley Livia dared go. She would go down those grassy slopes which were like velvet under her tender feet; she would dwell there among the nodding white blossoms, and no man would ever come to lay hot, rude hands on her. Conan had said that pacts were made to be broken; she would break her pact with him. She would go into the vale of the lost women—she would lose herself in solitude and stillness. . . . Even as these dreamy and disjointed thoughts floated through her consciousness, she was descending the gentle slopes, and the tiers of the valley walls were rising higher on each hand.

But so gentle were their slopes that when she stood on the valley floor, she did not have the feeling of being imprisoned by rugged walls. All about her floated seas of shadow, and great white blossoms nodded and whispered to her. She wandered at random, parting the fronds before her with her small hands, listening to the whisper of the wind through the leaves, finding a childish pleasure in the gurgling of an unseen stream. She moved as in a dream, in the grasp of a strange unreality. One thought reiterated itself continually: there she was safe from the brutality of men. She wept, but the tears were of joy. She lay full length upon the sward and clutched the soft grass as if she would crush her new-found refuge to her breast and hold it there forever.

She plucked the petals of the great white blossoms and fashioned them into a chaplet for her golden hair. Their perfume was in keeping with all other things in the valley, dreamy, subtle, enchanting.

So she came at last to a glade in the midst of the valley, and saw there a great stone, hewn as if by human hands, and adorned with ferns and blossoms and chains of flowers. She stood staring at it, and then there was movement and life about her. Turning, she saw figures stealing from the denser shadows—slender brown women, lithe, naked, with blossoms in their night-black hair. Like creatures of a dream they came about her, and they did not speak. But suddenly terror seized her as she looked into their eyes. Those eyes were luminous, radiant in the starshine; but they were not human eyes. The forms were human, but in the souls a strange change had been wrought; a change reflected in their glowing eyes. Fear descended on Livia in a wave. The serpent reared its grisly head in her new-found Paradise.

But she could not flee. The lithe brown women were all about her. One, lovelier than the rest, came silently up to the trembling girl, and enfolded her with supple brown arms. Her breath was scented with the same perfume that stole from the great white blossoms that waved in the starshine. Her lips pressed Livia’s in a long terrible kiss. The Ophirean felt coldness running through her veins; her limbs turned brittle; like a white statue of marble she lay in the arms of her captress, incapable of speech or movement.

Quick soft hands lifted her and laid her on the altar-stone amidst a bed of flowers. The brown women joined hands in a ring and moved supplely about the altar, dancing a strange dark measure. Never the sun or the moon looked on such a dance, and the great white stars grew whiter and glowed with a more luminous light as if its dark witchery struck response in things cosmic and elemental.

And a low chant arose, that was less human than the gurgling of the distant stream; a rustle of voices like the whispering of the great white blossoms that waved beneath the stars. Livia lay, conscious but without power of movement. It did not occur to her to doubt her sanity. She sought not to reason or analyze; she was and these strange beings dancing about her were; a dumb realization of existence and recognition of the actuality of nightmare possessed her as she lay helplessly gazing up at the star-clustered sky, whence, she somehow knew with more than mortal knowledge, some thing would come to her, as it had come long ago to make these naked brown women the soulless beings they now were.

First, high above her, she saw a black dot among the stars, which grew and expanded; it neared her; it swelled to a bat; and still it grew, though its shape did not alter further to any great extent. It hovered over her in the stars, dropping plummet-like earthward, its great wings spread over her; she lay in its tenebrous shadow. And all about her the chant rose higher, to a soft paean of soulless joy, a welcome to the god which came to claim a fresh sacrifice, fresh and rose-pink as a flower in the dew of dawn.

Now it hung directly over her, and her soul shrivelled and grew chill and small at the sight. Its wings were bat-like; but its body and the dim face that gazed down upon her were like nothing of sea or earth or air; she knew she looked upon ultimate horror, upon black cosmic foulness born in night-black gulfs beyond the reach of a madman’s wildest dreams.

Breaking the unseen bonds that held her dumb, she screamed awfully. Her cry was answered by a deep menacing shout. She heard the pounding of rushing feet; all about her there was a swirl as of swift waters; the white blossoms tossed wildly, and the brown women were gone. Over her hovered the great black shadow, and she saw a tall white figure, with plumes nodding in the stars, rushing toward her.

“Conan!” The cry broke involuntarily from her lips. With a fierce inarticulate yell, the barbarian sprang into the air, lashing upward with his sword that flamed in the starlight.

The great black wings rose and fell. Livia, dumb with horror, saw the Cimmerian enveloped in the black shadow that hung over him. The man’s breath came pantingly; his feet stamped the beaten earth, crushing the white blossoms into the dirt. The rending impact of his blows echoed through the night. He was hurled back and forth like a rat in the grip of a hound; blood splashed thickly on the sward, mingling with the white petals that lay strewn like a carpet.

And then the girl, watching that devilish battle as in a nightmare, saw the black-winged thing waver and stagger in mid-air; there was a threshing beat of crippled wings, and the monster had torn clear and was soaring upward to mingle and vanish among the stars. Its conqueror staggered dizzily, sword poised, legs wide-braced, staring upward stupidly, amazed at victory, but ready to take up again the ghastly battle.

An instant later Conan approached the altar, panting, dripping blood at every step. His massive chest heaved, glistening with perspiration. Blood ran down his arms in streams from his neck and shoulders. As he touched her, the spell on the girl was broken, and she scrambled up and slid from the altar, recoiling from his hand. He leaned against the stone, looking down at her, where she cowered at his feet.

“Men saw you ride out of the village,” he said. “I followed as soon as I could, and picked up your track, though it was no easy task following it by torchlight. I tracked you to the place where your horse threw you, and though the torches were exhausted by then, and I could not find the prints of your bare feet on the sward, I felt sure you had descended into the valley. My men would not follow me, so I came alone on foot. What vale of devils is this? What was that thing?”

“A god,” she whispered. “The black people spoke of it—a god from far away and long ago!”

“A devil from the Outer Dark,” he grunted. “Oh, they’re nothing uncommon. They lurk as thick as fleas outside the belt of light which surrounds this world. I’ve heard the wise men of Zamora talk of them. Some find their way to Earth, but when they do, they have to take on earthly form and flesh of some sort. A man like myself, with a sword, is a match for any amount of fangs and talons, infernal or terrestrial. Come, my men await me beyond the ridge of the valley.”

She crouched motionless, unable to find words, while he frowned down at her. Then she spoke: “I ran away from you. I planned to dupe you. I was not going to keep my promise to you. I was yours by the bargain we made, but I would have escaped from you if I could. Punish me as you will.”

He shook the sweat and blood from his locks, and sheathed his sword.

“Get up,” he grunted. “It was a foul bargain I made. I do not regret that black dog Bajujh, but you are no wench to be bought and sold. The ways of men vary in different lands, but a man need not be a swine, wherever he is. After I thought awhile, I saw that to hold you to your bargain would be the same as if I had forced you. Besides, you are not tough enough for this land. You are a child of cities, and books, and civilized ways—which isn’t your fault, but you’d die quickly following the life I thrive on. A dead woman would be no good to me. I will take you to the Stygian borders. The Stygians will send you home to Ophir.”

She stared up at him as if she had not heard aright. “Home?” she repeated mechanically. “Home? Ophir? My people? Cities, towers, peace, my home?” Suddenly tears welled into her eyes, and sinking to her knees, she embraced his knees in her arms.

“Crom, girl,” grunted Conan, embarrassed, “don’t do that; you’d think I was doing you a favor by kicking you out of this country; haven’t I explained that you’re not the proper woman for the war-chief of the Bamulas?”