Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The Howard Collector #12 (Spring 1970). This is taken from Howard’s typescript (a few typos have been corrected),

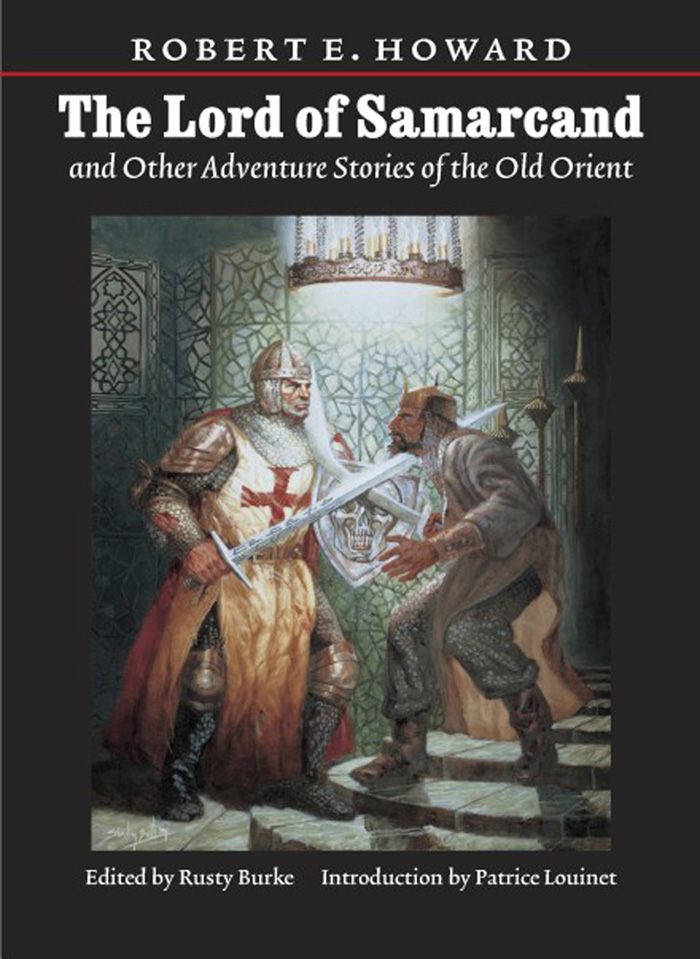

as found in The Lord of Samarcand and Other Adventure Tales of the Old Orient (University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

(The cover says “Stories” while inside it has “Tales.”)

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 |

Through the flaming riot of color which was the streets of Tyre strode a figure alien and incongruous. There was no lack of foreigners in this, the world’s richest capital, where purple-sailed ships brought the wealth of many seas and many lands. Among the native merchants and traders, with their slaves and guards, walked dark-skinned Egyptians, light-fingered thieves from beyond Lebanon, lean wild tribesmen from the south—Bedouins from the great desert—glittering princes of Damascus, with their swaggering retinues.

But there was a certain kinship evident among all these various peoples, a likeness betokening the Orient in each. The stranger, toward whom all eyes turned as he stalked by, was just as obviously alien to the East.

“He is a Greek,” whispered a crimson-robed courtier to a companion whose garb, no less than his wide-legged rolled gait, spoke of the sea. The captain shook his head.

“He is like them, yet unlike; he is of some kindred, but wilder, race—a barbarian from the north.”

The man under discussion did resemble certain types still found among the Grecians in that his shock of hair was yellow, his eyes blue, and his skin white, contrasting to the dark complections about him. But the hard, almost wolfish lines of his mighty frame were not Grecian. Here was a man who was akin to the original Hellenes, but who was much nearer the pristine Nordic stem—a man whose life had been spent, not in marble cities or fertile agricultural valleys, but in savage conflict with nature in her wildest form. This fact showed in his strong moody face, in the hard economy of his form—his heavy arms, broad shoulders, and lean loins. He wore an unadorned helmet and a scale-mail corselet, and from a broad gold-buckled girdle hung a long sword and a Gaulish dagger with a double-edged blade, fourteen inches in length, and broad as a man’s palm near the hilt—a terrible weapon, one edge slightly convex, the other correspondingly concave.

If the stranger was the object of curiosity, he no less evinced a like emotion in his scrutiny of the city and its inhabitants—a curiosity and wonder so evident that it would have seemed childish except for a certain underlying aspect of potential menace. There was a dangerous individuality about the barbarian which would not be submerged by his wonder at the strange environs among which he found himself.

And strange they were to him, who had never seen such luxury and wealth so carelessly spread out before him. Paved streets were strange to him, and he stared amazed at the buildings of stone and cedar and marble, decorated with gold, silver, ivory and precious stones. He blinked his eyes at the glitter which attended the procession of a notable or visiting prince along the streets—the exalted one lolling on silken cushions in a gem-crusted, silken-canopied litter, borne by slaves clad in silken loin-cloths, and followed by other slaves waving fly-flaps of ostrich-feathers, having jeweled handles—accompanied by soldiers in gilded helmets and bronze hauberks—Syrians, Tyreans, Ammonites, Egyptians, rich merchants from the isle of Kittim. He stared at their garments of the famous Tyrean purple, the dye on which the Phoenician empire had been founded, and by the pursuit of the elements of which Mesopotamian civilization had spread around the world. By virtue of their apparel the throngs of nobles and merchants were transformed from prosaic tradesmen, bent on cheating their neighbors, to princes questing from far for the glory of the gods. Their cloaks swung and shimmered in the sun—red as wine, darkly purple as a Syrian night, crimson as the blood of a murdered king.

Through the shifting rainbow colors and the gay-hued maze wandered the yellow-haired barbarian, his cold eyes filled with wonder, apparently unaware of the curious glances that were directed at him, or the bold-eyed stares of dark tinted women—walking in their sandals along the street, or borne in their canopied litters.

Now down the street came a procession whose wails and howls cut through the din of barter and contention. Hundreds of women ran along, half-naked and with their black hair streaming wildly down their shoulders. As they ran they beat their naked breasts and tore their hair, screaming as with grief too great to be borne in silence. Behind them came men bearing a litter on which lay a still form, covered with flowers. All the merchants and the keepers of stalls turned to look and listen.

Now the curious barbarian understood the cry which the women screamed over and over. “Thammuz is dead!”

The yellow-haired stranger turned to a loiterer who had ceased his contentions with a shopkeeper over the price of a garment, and said, in barbaric Phoenician: “Who is the great chief they are bearing to his long rest?”

The other looked up the street, and then, without replying, opened his mouth to the fullest capacity and bawled, “Thammuz is dead!”

All up and down the street men and women took up the cry, repeating it over and over, until a hysterical note was apparent, and the wailers began to sway their bodies and rend their garments.

Still puzzled, the tall stranger plucked at the loiterer’s sleeve, and repeated his question: “Who is this Thammuz, some great king of the East?”

Angered at the intrusion, the other turned and shouted wrathfully, “Thammuz is dead, fool, Thammuz is dead! Who are you to interrupt my devotions?”

“My name is Eithriall, and I am a Gaul,” answered the other, nettled. “As for your devotions, you are doing naught except stand there and bellow ‘Thammuz is dead’ like a branded bull!”

The Phoenician glared, and then began howling at the top of his voice, “He defames Thammuz! He defames the great god!”

The litter was passing along by the disputants now, and it halted as the bearers, yelling as loudly as they could, nevertheless were attracted by the antics of the worshipper and his words. The litter halted, and scores of dark eyes, not entirely sane, were turned toward the Gaul. A throng was gathering, as it always gathers in Oriental cities; the shout was repeated in high-pitched screams, the wailers weaving and swaying, foam flying from their lips in slobbering ecstasy, as they lashed themselves into religious frenzy. The most level-headed and unemotional race in the world, in ordinary moments, the Phoenicians were not free from the frenzied outbursts of emotions common to all Semites in regard to their devotions of the gods.

Now hands settled on dagger hilts and eyes flamed murderously in the direction of the yellow-haired giant, against whom the emotion-drunk loiterer still hurled his accusation.

“He defames Thammuz!” howled the foaming devotee.

A rumbling growl rose from the crowd, and the litter tossed like a boat on a stormy sea. The Gaul laid his hand on his sword, and his blue eyes glinted icily.

“Go your way, people,” he growled. “I’ve said nothing against any god. Go in peace and be cursed to you.”

Half heard in the growing clamor, his faulty Phoenician was misunderstood; the crowd only caught the oath. Instantly there rose a savage yell: “He curses Thammuz! Slay the violator!”

They were all around him, and they swarmed on him so quickly that for all his speed, he had not time to draw his sword. Maddened by their own religious frenzy, the crowd swept upon him, overthrowing him. As he went down he dealt a terrible buffet to his foremost attacker—the misguided loiterer—and the man’s neck broke like a twig. Frantic heels lashed at him, frenzied fingers clawed at him, daggers flashed wickedly. Their own numbers hampered them; blood spurted and howls different from the cries of madness rose, as the hacking blades found marks unintended. Borne down by the mass of their numbers, Eithriall tore out his great dagger, and a scream of agony knifed the din as it sank home. The press gave suddenly before the deadly play of the glittering blade, and Eithriall heaved up, throwing men aside like ten-pins right and left. The wave of battle had washed over the litter; it lay in the dust of the street, and Eithriall grunted in astonishment and disgust as he realized the nature of its burden.

But the maddened worshippers were surging back upon him, blades flashing like the spume of an on-rolling wave. The foremost slashed at him savagely, but Eithriall ducked and swayed, ripping as he rolled, so that the stroke was one with the motion of his body. The attacker shrieked and fell as if the legs of him had suddenly given way—almost cut in half.

Eithriall leaped back from the humming blades, and his great shoulders struck hard against a door, which gave inward, precipitating him backward. Such was the momentum of his leap that he fell sprawling on his back, within the door. So quickly did he rise from his inglorious fall that he seemed to rebound from the floor like a cat—then he stopped short and stood glaring, his dripping dagger gripped in his hand.

The door was shut, and a man was throwing the bolt in place. As the Gaul stared in surprise, this man turned with a laugh, and moved toward an opposite door, motioning him to follow. Eithriall complied, walking warily and suspicious as a wolf. Outside the mob raved, and the door groaned and buckled to their impact. Then the stranger led the way into a dark, narrow, winding alley, and up this they went, meeting no one, until the roar of the throng faded to a whisper behind them. Then the man turned aside into a doorway, and they emerged into an inn, where a few men sat cross-legged and argued in the everlasting contentions of the East.

“Well, my friend,” said the Gaul’s rescuer, “I think that we have thrown the hounds off the scent.”

Eithriall looked at him dubiously, and realized a certain kinship. The man was certainly no Phoenician. His features were as straight as the Gaul’s own. He was tall and well-knit, not much inferior in stature to the giant Gaul. His hair was black, his eyes gray; he appeared to be of early middle-life, and though he wore Eastern apparel, and spoke Phoenician with a Semitic accent, Eithriall knew that he had met a descendant of ancestors common to them both—the roving Aryans who peopled the world with light eyed, fair haired drifts.

“Who are you?” the Gaul asked bluntly.

“Men call me Ormraxes, the Mede,” answered the other. “Let us sit here and drink wine; fleeing is thirsty work!”

They sat them down at a rough-hewn table, and a servant brought wine. They drank in silence. Eithriall was brooding over the past events, and presently he said, “I need not thank you for barring that door and leading me to safety. By Crom, these folks are all mad. I did but ask what king they bore to his tomb, and they flew at me like wildcats. And there was no corpse in that litter after all—only a wooden image, decorated with gold and jewels, drenched in rancid oil, and decked with flowers. What—”

He started up, drawing his sword, as in a nearby street a clamor broke forth afresh.

“They have forgotten all about you,” laughed Ormraxes. “Be at ease.”

But Eithriall went to the door and cautiously looked out through a crack. Looking along a winding street, he had a glimpse of another, larger street; down this the procession was marching, but the nature was greatly changed; the flower-decked image was borne upright on the shoulders of the votaries, and men and women were dancing and singing, shouting with rapture, as extravagant in their joy as they had been in their grief.

Eithriall snorted in disgust.

“Now they howl ‘Adonis is living,’ ” said he. “A short space agone it was ‘Thammuz is dead,’ and they rent their garments and gashed themselves with daggers. By Crom, Ormraxes, I tell you they are mad!”

The Mede laughed and lifted his goblet.

“All these people go mad during their religious festivals. They are celebrating the resurrection of the god of life, Adonis-Thammuz, who is slain in midsummer by Baal-Moloch, the Sun. They carry the dead image of the god first, then revive him and hail him as you have seen. This is nothing—you should see the worshippers at Gebal, the holy city of Adonis there they cut themselves to pieces in their frenzy, and throw themselves down to be trampled to dust by the throngs.”

The Gaul digested this statement for a space, then shook his head in bewilderment and drank hugely. Presently a question occurred to him.

“Why did you risk your life to aid me?”

“I saw you fighting with the mob. There was no fairness in it—a thousand to one. Besides, there is kinship between us—distant, and dim, yet the blood tie is there.”

“I have heard of your people,” answered Eithriall. “They dwell far to the north, do they not?”

“Beyond the lands of Nairi and the headwaters of the Euphrates,” answered Ormraxes. “Slowly they have drifted southward from the steppes; year by year they encroach on the valleys of the Alarodians. Others have drifted singly and in small bands down the Euphrates and the Tigris as mercenary soldiers. This drift has been going on for three or four generations.”

“Are you a native, then, of this country?” asked the Gaul.

“Not of Phoenicia. I was born in the valleys of the Nairi, and wandered south as a hunter and mercenary. I came upon a people distantly akin to my tribe on the borders of Ammon, and abode there.”

Eithriall made no comment. He knew no more of Ammon than he did of Atlantis. But there was something in his mind, and he gave voice to his thought.

“Tell me—in your goings about, and your wanderings and your travels throughout the land, have you seen or heard of a man named Shamash?”

Ormraxes shook his head.

“It is an Assyrian name; thus they name one of their gods. But I never saw a man given the bare name, unless modified, such as Ishmi-Shamash, or Shamash-Pileser. What manner of man is he?”

“Of good height—though not so tall as either of us—and strongly made. His eyes are dark, and his hair is blue-black; likewise his beard, which he curls. His bearing is bold and arrogant; he is like these Tyreans, yet strangely unlike, for where they cringed and whined, he strode domineeringly; and where they avoid battle, he sought it. Nor were his features much like them, though his nose was hooked, and his countenance somewhat of the same cast.”

“Truly you have described an Assyrian,” said Ormraxes with a laugh. “To the southeast, beyond the Euphrates, there are thousands of men who would answer your description, nor need you go that far, it may be, for there is war in the wind and Shalamanu-usshir, king of Assyria, comes up with his war-chariots to war against the princes of Syria—or so men whisper in the market-places.”

“Who is this Shalmaneser?” asked the Gaul, making a jumble out of the Semitic pronunciation.

“The greatest king of all the earth, whose empire stretches from the southern valleys of the Nairi to the Sea of the Rising Sun, and from the mountains of Zagros to the tents of the Arabians. Assyria is his, and Karkhemish of the Hittites, Babylonia and the marshes of Chaldea. His fathers the kings dwelt aforetime in Asshur and Nineveh, but he has built Kalah to be a royal city and gemmed it with palaces, like jewels set in the hilt of a sword.”

Eithriall looked dubiously at his companion; these lapses into sonorous language were Semitic rather than Aryan, but Eithriall realized that the Mede must have spent most of his life among Orientals.

“And the chiefs of Syria,” quoth the Gaul, “are they whetting their axes and preparing for the onslaught?”

“So men say,” answered the Mede warily.

“I have no gold,” muttered the Gaul. “Which of these kings will pay me the most for my sword?”

Ormraxes’ eyes glinted, as if it were a remark for which he had been waiting. He leaned forward, opened his lips to speak—a shout interrupted him. Like a steel spring released he shot to his feet and wheeled, sword flashing into his hand.

At the outer door stood a band of soldiers in gleaming armor; with them was a noble in a purple cloak, and a ragged rogue who had slipped out of the inn when the companions entered. This rascal pointed at the Mede and shouted, “It is he! It is Khumri!”

“Quick!” whispered the Mede. “Out the side-door!”

But even as he turned, and Eithriall sprang up to follow him, this door was dashed open and a squad of soldiers poured in. Snarling like a cat, Ormraxes sprang back, and at the order of the purple-clad noble, the soldiers rushed in. The Mede cleft the skull of the foremost, parried a spear and sprang toward the noble who retreated, howling for help. The soldiers ringed him, and one, running in, pinioned Ormraxes’ arms from behind. Eithriall’s sword decapitated the fellow, and back to back the comrades made their stand. But the inn was swarming with soldiers. There was a terrific clashing of steel, yells of wrath and shrieks of pain, then a blasting charge swept the companions apart by sheer force. Eithriall was hurled back against an up-ended table, with a half dozen swords hacking for his life. Dripping blood, he roared, and disemboweled a soldier with a ferocious rip of his sword—then an iron mace crashed thunderingly on his helmet. Reeling, blind, he strove to fight back, but blow after blow rained on his iron-clad head, beating him slowly, relentlessly to the floor, like the felling of a great tree. Then he knew no more.

Eithriall recovered consciousness slowly. His head ached and throbbed, and his limbs felt stiff. There was a light in his eyes, which he recognized as a candle. He was in a small stone-walled chamber—evidently a cell, he thought—on a couch, and a man was bending over him, dressing his wounds. They did not want him to die so easily, the Gaul thought; they revived him to torture him. So he gripped the man by the throat like a python striking, before the victim realized that he had recovered consciousness. Other men were in the room, but no blows rained on the Gaul, as he expected, only a hand fell on his shoulder, and a voice cried in Phoenician: “Wait! Wait! Don’t slay him! He is a friend! You are among friends!”

The words carried conviction, and Eithriall released his captive, who owed his life only to the fact that the Gaul had not fully recovered his usual powers. The fellow fell to the floor, gasping and gagging, where other men seized him and beat him lustily on the back and poured wine down his throat, so that presently he sat up and regarded his strangler reproachfully. The first speaker tugged at his beard absently and regarded Eithriall meditatively. This man was of medium height, with characteristic Phoenician features, and was clad in crimson robes that denoted either the nobleman or the wealthy merchant.

“Bring food and drink,” he ordered, and a slave brought meats and a great flagon of wine. Eithriall, realizing his hunger, gulped down a gigantic amount of the liquor, and seizing a huge joint in both hands, began to wolf down the meat, tearing large morsels off with his teeth which were as strong as those of a bear. He did not ask the why and wherefore of it all; lean years had taught the barbarian to take food as it came.

“You are a friend of Khumri?” asked the crimson-clad person.

“If you mean the Mede,” the Gaul answered between bites, “I never saw him until today, when he doubtless saved my life from a mob. What have you done with him?”

The other shook his head.

“It was not I who took him—I only wish it had been. It was the soldiers of the king of Tyre who seized him. They bore him to the dungeons. You I found lying senseless in the alley behind the inn, where they had thrown you. Perhaps they thought that you were dead. But there you lay on the cobble-stones, your sword still gripped in your hands. I had my servants take you up and bring you to my house.”

“Why?”

The person did not reply directly.

“Khumri saved your life; do you wish to aid him?”

“A life for a life,” quoth the Gaul, smacking his lips over the wine. “He aided me; I will aid him, even to the death.”

It was no idle boast. Beyond the frontiers of civilization, obligations were real, and men aided men from dire necessity, until it had become a veritable religion among the barbarians to repay such debts. The crimson-robed one knew this, for he had roved far, and his wanderings had taken him much among the yellow-haired peoples of the west.

“You have lain senseless for hours,” he said. “Are you able to run and fight now?”

The Gaul rose and stretched his massive arms, towering above the others.

“I have rested, eaten and drunk,” he grunted. “I am no Grecian girl to fall down and die of a tap on the head.”

“Bring his sword,” ordered the leader, and it was brought. Eithriall thrust it into his scabbard with a grunt of satisfaction, at the same time involuntarily making sure that his great dagger was in place at his girdle. Then he looked inquiringly at the crimson-robed man.

“I am a friend of Khumri,” said the man. “My name is Akuros. Now harken to me. It is nearly midnight. I know where Khumri is confined. He is kept in a dungeon not far from the wharfs. In this prison there is an outer set of guards, and an inner guard. I will dispose of the outer guard; they are Philistines, and I will send a man to bribe them to desert their post. But the inner guard is composed of Assyrians, and they can not be bribed. But there will be only three of them, and with cunning you can dispose of them.”

“Leave them to me,” growled the Gaul. “But where is this dungeon? And having gotten Ormraxes his liberty, what shall we do then?”

“I will send a man to guide you to the prison,” answered Akuros. “If you get Khumri free, the same man will be waiting to guide you to the wharfs, where a boat will await you. Tyre is built upon islands, as you know, and you could never get through the gates of the wall which shuts the city from the mainland. I can not aid Khumri openly, but I will do all I can secretly.”

Eithriall asked of Shamish.

In a short time Eithriall was following a stealthy figure along dark winding alleys. The man went stealthily but for all his stature, the Gaul made no more noise than a wind whispering through a forest. Only occasionally enough starlight filtered between the slumbering walls to strike pale gleams from his corselet scales, helmet or sword. At last they halted in a shadowed alley-mouth and the guide pointed to a squat stone edifice before which a clump of mailed figures stood, in the light of torches guttering in niches in the stone wall. They were conversing with a man whose features were hidden by a mask, and a heavy, small bag, which sagged significantly, passed between them. Then the masked man wrapped his cloak about him and disappeared in the shadows, and the soldiers went quickly and silently in another direction.

“They will not return,” murmured Eithriall’s guide. “The lord Akuros had them given enough gold to allow them to desert the army. They’ll be drunk for weeks. Go quickly, my lord! There are more guards within.”

The Gaul glided from the alley and approached the prison, whose iron door was not bolted. He opened it cautiously, staring within. A few torches in niches lighted a bare corridor dimly. It was empty to its turn, but beyond the bend he heard a confused murmur of voices, and saw more light. He went silently down the corridor, and halted at the bend. A flight of stone steps went down, and in the lower corridor, he saw three broad-built, powerful figures in helmets and mail—black bearded men, with cruel, dominant features. He thought of an ancient foe, and his hair bristles as a hound bristles at sight of an enemy. They were gambling on the stone floor, and their words were in a strange tongue. But as he looked, a stocky individual came out of the shadows, and spoke in Phoenician: “In an hour the king’s men will come for the prisoner.”

“Have you been questioning him?” one of them demanded in the same tongue.

“He’s stubborn like all his breed,” answered the Tyrean. “Little matter; Shalamanu-usshir will be glad to receive him. What think you the great king’s greeting will be to the lord Khumri?”

“He will have him flayed alive,” answered the Assyrian, after a judicial pause.

“Well, see to him well. He’s shackled hand and foot, but he’s a very desert lion. I go to the king.”

The Assyrians bent to their game again, and the Phoenician waddled up the stone steps. Eithriall glided back from the bend where the stair began, and flattened himself against the wall, in the shadows. The Phoenician came up around the turn, started down the corridor—just as he was opposite the Gaul, so close that an outstretched hand would have touched him, some instinct caused him to wheel. The light was dim, the shadows ghostly. Perhaps the Phoenician thought he saw a specter. Perhaps the sight of the yellow-haired giant in his gleaming mail froze him for an instant. That instant was enough. Before a sound could come from his gaping mouth, Eithriall’s great sword cleft his skull and he fell at the Gaul’s feet.

Eithriall sprang back quickly to the angle of the wall. Below him he heard a clatter of falling dice as the Assyrians sprang up, startled. He dared not risk a look, but he heard a muffled babble of contention, then the sound of three men mounting the stair. Looking about desperately, the Gaul saw an iron ring in the wall above his head—doubtless used for the suspension of tortured prisoners. Leaping he caught it and drew himself up. His groping foot found a slight depression in the wall, where a bit of the masonry had crumbled, and digging his toe in, he hung precariously there. The Assyrians had climbed the stair and their language broke out afresh as they stumbled upon the body of the Phoenician, lying in his own blood. Spears ready, they looked all about, but it did not occur to them to look up. One of them started toward the outer entrance, evidently in quest of the outer guard—it was at that moment that Eithriall’s foothold gave way.

In such crises the Gaul’s brain worked like lightning. Even as his foot slipped he released the ring, and as he fell he knew what he meant to do, whereas the soldiers, taken completely off guard, were caught flat-footed. Eithriall’s knee struck between the shoulders of one of them, crushing him to the floor; rebounding with catlike quickness, the Gaul avoided the wavering clumsy spear-thrust aimed at him by another, who was too amazed to be coordinate. Eithriall’s sword hummed and the point tore through the corselet scales, to stand out behind the soldier’s shoulders. But the very fury of that stroke almost proved the Gaul’s undoing. The other Assyrian, in the flashing instant that had transpired since the barbarian’s fall, had recovered his wits, and now ran fiercely at his enemy, spear ready for the death-thrust.

Eithriall tugged savagely at his hilt, but the blade was wedged in the dead man’s breast bone, and the charging Assyrian was looming upon him. Releasing the locked sword, Eithriall wheeled empty-handed to meet the charge. The driving spear broke on his mail, knocking the wind out of him with an explosive grunt, and the force of the Assyrian’s attack dashed him headlong against the Gaul. Eithriall staggered backward beneath the impact, and felt empty space under his feet. He had been borne back over the stairway, and now, close-clinched, they tumbled down the steps, heels over head, their armor clashing on the stone. In the headlong speed of that descent, there was no time for either to strike a blow or make any plan of action. A flashing, chaotic instant of helpless falling and then Eithriall realized that their descent had ceased, and that the soldier lay motionless beneath him. Dazedly the Gaul arose, groping instinctively for his helmet which had fallen off. The Assyrian lay still; his neck was broken.

Eithriall found and donned his helmet, then looked about. Cells opened on the corridor, but they were dark; but through a slit in the door of one, toward the other end of the corridor, a light shone dimly. A quick search proved that a bunch of heavy iron keys was fastened to the dead soldier’s girdle. With these Eithriall unlocked the door, and saw Ormraxes the Mede lying on the stone floor, weighted with heavy chains. The Mede was awake—indeed the sound of that fall of mailed men down the stair had almost wakened a dead man.

He grinned as Eithriall entered, but said nothing. The Gaul, after some fumbling, found the keys that unlocked the shackles, and Ormraxes, or Khumri, stood up free, stretching his limbs. His glance questioned the Gaul, who, motioning for silence, led the way up the corridor. At the head of the stair, Eithriall recovered his sword with much tugging and silent swearing, and Ormraxes took up a spear belonging to the slaughtered guards. They warily left the prison and went to the alley where the Gaul’s guide awaited them. He motioned them to follow and they went along through a shadowed labyrinth and emerged on an open space. Eithriall heard the lap of waters at hidden piles, and saw the starlight on the waves. They were standing on a small wharf.

A boat was drawn up there, the rowers at the oars. Eithriall and Ormraxes entered the boat, the guide following them, and the rowers pushed off. Behind them the lights of Tyre blended into a sea of myriad dancing sparks. A breeze whispered across the bay. The tang of dawn was in the air. On the mainland ahead of them another light sprang up, and toward it the boatmen rowed.

As they approached this light was seen to be a torch held in the hand of one of a small group of men standing on the beach, near the water’s edge. They had left the city far to the left. The stretch of beach was deserted and bare even of fishing huts.

As the boat was grounded, and Eithriall followed Ormraxes ashore, he saw that one of the men was Akuros. Behind him his servants held horses.

“My lord,” said Akuros to Ormraxes, “my plan has worked out more perfectly than I had hoped.”

“Yes, thanks to this Gaul,” laughed the Mede.

“I could not venture to aid you more openly,” said the Phoenician. “Even now my life is forfeit if I am not ten times more wary than a fox. But you—you will remember?”

“I will remember,” answered Ormraxes. “The princes of Syria will not move against Tyre after we have scattered the chariots of the Assyrian. And from you, Akuros, will I buy all cedar and lapis-lazuli and precious stones, even as I promised.”

“I know that the lord Khumri keeps his word,” said Akuros, with a deference Eithriall did not understand. “Here are horses, my lord. I dare not send an escort, lest I be suspected—”

“We need no escort, good Akuros,” broke in Ormraxes. “And now we bid you farewell; the dawn is nigh and we have far to ride.”

They swung into the saddle and headed eastward. Eithriall, looking back from his saddle, saw afar across the bay, the glittering ocean of lights that was Tyre; and on the shore, limned in the torch-light, the crimson-robed figure of Akuros, hand lifted in salute.