Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

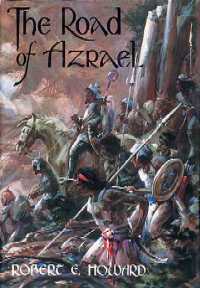

Published in The Road of Azrael, 1979. This version is taken from Howard’s original typescript (a few typos have been corrected),

as found in The Lord of Samarcand and Other Adventure Tales of the Old Orient (University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

As the moon glided from behind a mass of fleecy clouds, etching the shadows of the woods in a silvery glow, the man sprang into a dark clump of bushes, like a hunted thing that fears the disclosing light. As a clink of shod hoofs came plainly to him, he drew further back into his covert, scarcely daring to breathe. In the silence a nightbird called sleepily, and he heard, in the distance, the lazy lap of waters against the shore. The moon slid again behind a drifting cloud, just as the horseman emerged from the trees on the other side of the small glade. The man, hugging his covert, cursed silently. He could make out only a vague moving mass; could hear only the clink of stirrups and the creak of leather. Then the moon came out again, and with a deep gasp of relief, the hider sprang from among the bushes.

The horse reared and snorted, the rider yelped a startled oath, and a short spear gleamed in his lifted hand. The apparition which had so suddenly sprung to his horse’s head was not one calculated to reassure a lonely wayfarer. It was a tall, rangily powerful man, naked but for a loin cloth, his steely muscles rippling in the moonlight.

“Back, or I run you through!” snarled the horseman, in Turki. “Who are you, in Satan’s name?”

“Roger de Cogan,” answered the other in Norman-French. “Speak softly. We are scarce a mile from a Moslem rendezvous, and they may have scouts out. I marvel that you have not been taken. Up the shore, in a small bay screened with tall trees, there are three galleys hidden, and I saw the glitter of arms ashore. This night I escaped from the galley of the famed pirate, the Arab Yusef ibn Zalim, where I have toiled for months at the oars. He made the rendezvous, for what reason I know not, but fearing treachery of some sort from the Turks, anchored outside the bay. And now he lies at the bottom of the gulf, for I broke my chain, came quietly upon him as he drowsed in the bows, strangled him, and swam ashore.”

The horseman grunted, sitting his horse like a statue, etched in the moonlight. He was tall, clad in grey chain-mail which did not hide the hard lines of his rangy limbs, an iron cap pushed back carelessly on his steel-hooded head. Even in the uncertain light, the fugitive was impressed by the man’s hawk-like, predatory features.

“I think you lie,” he said, speaking Norman-French with a peculiar accent. “You a galley slave, with your hair new cropped and your face freshly shaven? And what Moslem galleys would dare hide on the European shore, so close to the city?”

“Why, by God,” answered the other in evident surprize, “you can not deny that I am a Christian. As to my hair and beard, I think it a poor thing that a cavalier should allow himself to become sloven, even in captivity. One of the captives on board the galley was a Greek barber, and only this morning I prevailed upon him to shear and shave me. As for the other, all men know that the Moslems steal up and down the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmora almost at will. But we risk our lives standing here babbling. Give me a stirrup and let us be gone.”

“I think not,” muttered the horseman. “You have seen too much.”

And with a powerful heave of his whole frame, he drove the spear straight toward the other’s broad breast. So unexpected was the action, that it was only the instinctive movement of the victim which saved him. Caught flat-footed, his steel-trap coordination yet electrified him a flashing fraction of an instant quicker than the driving steel, which cut the skin on his shoulder as it hissed past him. But it was not blind instinct which caused him to grasp the spearshaft and jerk back savagely. Rage at the unprovoked woke the killing lust in his brain. The avoiding of the blow and the jerk at the spear-shaft were the work of an instant. Over-reached and off balance from the missed stroke, the horseman tumbled headlong from the saddle, full on his antagonist’s breast, and they crashed to the ground together, the horseman’s carelessly worn helmet falling from his head. The horse snorted and bolted to the edge of the trees.

The stranger had released the spear as he fell, and now, close locked, the fighters rolled across the open space and crashed among the bushes. The mailed hand clutched at the sheathed dagger, but de Cogan was quicker. With a volcanic heave, he reared himself above his antagonist, clutching a heavy stone on which his fingers had blindly closed. The dagger was out, gleaming in the moonlight, but before it could drive home the stone crashed with stunning force on the mail-clad head. The flexible coif was not enough protection against such a blow. The pliant links did not part, but they gave, and beneath them the striker felt the skull crunch under the blow. And with fully roused ferocity, the ex-slave struck again and again, until his foeman lay motionless beneath him, blood seeping sluggishly from beneath the iron hood.

Then, panting, he rose, flinging aside the crude weapon, and glared down at the vanquished. Still shaken with fury and surprize, he shook his head bewilderedly. Then a sudden thought came to him, and he wondered that it had not occurred to him before. The horseman had come from the direction of the Moslem camp. Surely it had been impossible for him to have ridden past it unchallenged. He must have been in the camp itself. Then that meant that the fellow was somehow in league with the paynim, and again Roger shook his head. He had learned much of the ways of the East since he had ridden down the Danube in the vanguard of Peter the Hermit. Byzantine and Moslem were not always at each other’s throats. Sometimes they dealt together secretly, to the confounding of the westerners. But Roger had never heard of a Crusader turning renegade—and this man, in the armor of a Cross Wearer, was no Greek.

Yielding to urgent necessity, Roger began to strip the dead. The dead man was clean shaven, with square-cut yellow hair. As far as appearances went, he might have been a Norman, but de Cogan remembered his alien accent. The ex-galley slave hurriedly donned the harness, settled the sword belt more firmly about his lean loins, and looked about for the iron cap which he placed on his tawny locks. All fitted him as if made for him. Inch for inch, the unknown attacker and he had been a perfect match. He stroked the hilt of the long broad sword, and felt like a man again, for the first time in months. The clink of the scabbard against his mail-sheathed thigh reminded him that he was again Sir Roger de Cogan, knight of the Cross, and one of England’s surest swords.

No sound save the distant twittering of night birds disturbed the magic silence as he caught the charger which was calmly grazing at the edge of the woods. As he swung into the saddle, the long months of degradation and grinding toil fell away from him like a cast-off mantle, leaving only a grim determination to pay the debt he owed the worshippers of Muhammad. He smiled bleakly as he remembered the dying gurgles of Yusef ibn Zalim, but his face darkened as another visage rose before him, mocking in the moonlight—a lean hawk-face, crowned by a peaked helmet with a heron’s feather. Prince Othman, son of Kilidg Arslan, the Red Lion of the Seljuks. The phantom mocked, but there would be another day, and scant in all other things, Norman patience, when laid toward vengeance, was deep and abiding as the North Sea which bred it.

Roger left the spear where it lay, but he unslung the kite-shaped shield which hung at the saddle-bow, and wary as a wolf, plunged into the shadows of the trees, in the direction in which he had been going before the adventure. There was no insignia on the shield, but on the breast of the hauberk a strange emblem was worked in gold—something that looked like a falcon, and was unmistakably Grecian in its artistry.

The woods through which he rode were now as deserted as if he were the last man on earth. He followed the shore line as near as he dared, guiding his course by the distant lap of the waves, and the terrain was rolling and uneven. After some three hours, the lights of Constantinople blazed through the trees, as he mounted rises, then vanished as he dipped into hollows. It was, he calculated, somewhat past midnight when he rode into the outskirts of the city, which, separate from the greater metropolis and yet a part of it, sprawled along the northern bank of the Golden Horn. This was the quarters of the Venetian traders and other foreign merchants—straggling streets of carved wooden buildings and more substantial houses of stone. But before he reached the heart of the city, a wall halted him, and the watch at the gate hailed him. A torch in a mailed hand was reached down, to be brandished almost in his face, but before he could name himself, he saw a figure in black velvet lean from the wall and scrutinize him closely. There followed a few low words in Greek, and the gates swung open, to clang behind him as he reined his steed through. He prepared to ride away down the street, when the velveted figure darted out and caught his rein.

“Light! light!” exclaimed this person impatiently. “What is in your mind? Have you forgotten our master’s instructions? Here, Manuel, take this steed to the pier. Come with me, my lord Thorvald. Wait! Some one may recognize you! I had not known you, in those western trappings, and without your beard, but for the golden falcon on your hauberk. But some one might—take this silken scarf and mask your features with it.”

Sir Roger took it and wrapped in loosely about his coif, so that only his steely eyes were visible. It was apparent that he had been mistaken for the man he had slain. It was almost certain that he was going into danger, but it was as certain that if he declared his identity, he would just as quickly find himself in danger. The name of Thorvald stirred some faint recollection at the back of the Norman’s mind, and he instinctively touched the hilt of the sword at his girdle.

The guide led the way through narrow, deserted streets, until Roger knew that they were not far from piers that gave on to the strait, and halted at the door of a squat stone tower, evidently a relic of an earlier, ruder age. Some one looked out through a slit in the door.

“Open, fool!” hissed the man in velvet. “It is Angelus and the lord Thorvald the Smiter.”

Hinges creaked as the door swung inward. Sir Roger followed, in a maze of fantastic speculations. Thorvald the Smiter—so that was the man he had battered to death with a stone in the glade. He had heard of the Norseman who was the grimmest swordsman in the Varangian Guards, that band of mercenaries, Northern slayers maintained by the Greeks. He had seen them about the palace of the Emperor—tall bearded men, in crested helmets and scarlet-edged cloaks and gilded mail. But what was a Varangian captain doing riding from a Turkish rendezvous in the night, clad in the mail of a Crusader?

Roger began to feel that he had stepped into a pit full of hidden snakes in the dark, but he drew the scarf closer about his features, and followed his guide through a short dark corridor into a small, dim-lit chamber. Some one was sitting in a great ornate chair, and to this figure the guide bowed almost to the floor, and withdrew, closing the door behind him. The Norman stood straining his eyes, and as they became accustomed to the dim candle-light, the form in the chair slowly took form. It was a short, stocky man who sat there, wrapped in a plain dark satin cloak which hid all other details of his costume. A featherless slouch hat and a mask lay on a table close at hand, arguing that the man had come in secrecy, fearing recognition. The knight’s eyes were drawn to the other’s face; the blue-black beard was carefully curled, the dark locks bound back from the broad forehead with a cloth-of-gold band; beneath it wide brown eyes gleamed with an innate vitality. Sir Roger started violently. In God’s name, into what dark undercurrent of plot and intrigue had he fallen? The man in the chair was Alexis Comnene, emperor of the Byzantine empire.

“You have come quickly enough, Thorvald,” said the emperor—and Sir Roger did not reply, being too busy wondering what mysterious matter had brought the emperor of the East from his marble-pillared palace in the dead of night to an obscure tower in the outer city.

“You ride with a loose rein. The messenger I sent did not tell you why I wished your presence?”

Sir Roger shook his head, at a venture. Alexis nodded.

“I told him to only bid you hasten here. But tell me—in your cruisings among the Black Sea corsairs, have they ever suspected your true identity?”

Again Sir Roger shook his head.

Alexis smiled.

“Sparing of speech as ever, old wolf! It is well. But just now I have work for you even more important than keeping an eye on the Moslem pirates. So I sent for you—

“Thorvald, since you went spying among the Turks, the hosts of the Franks have come and gone. They did not come as came Peter the Hermit and Gautier-sans-Avoir—rabbles of paupers and knaves. They came with war-horses, and wagon trains, cavaliers, and women, archers, pikemen and men-at-arms—all afire with zeal for recovering the Holy Sepulcher.

“First came Hugh of Vermandois, brother of the French king, in a ship with a few attendants. I feasted him royally, made him rich gifts, and persuaded him to take oath of allegiance to me. Then came others—St. Gilles of Provence, Godfrey of Bouillon and his brothers, and that devil Bohemund. All took oath of fealty except the stubborn Count of Provence—but I fear him not. He is zealous, and all for Jerusalem. Bohemund is another matter; he would cut the throat of Saint Paul, to gratify his ambition.

“They took Nicea for me, but I tricked them out of it, sending Manuel Butumites to make a secret treaty with the Turks, and now the city is garrisoned with my soldiers. Now the host marches southward, toward Palestine, and in the hills of Asia Minor, Kilidg Arslan will doubtless cut all their throats. Yet it may be that they will prevail against him. At least, they will deal him such great blows that he will be no more a menace for Byzantium for years to come. Nay, I fear him less than I fear that devil Bohemund, whom naught but luck helped me to defeat some twelve years ago when he came up out of Italy with Robert Guiscard.

“Thorvald, I sent for you because there is no man east of the Danube able to stand against you in sword-play. I have laid my plans well, yet Bohemund has slipped through my fingers before. With the corsairs you have been my eyes and my brain; now you must be my sword. Your task is to see that Bohemund does not leave the field alive, when Kilidg Arslan comes up against the Franks. Hew not to the right nor to the left, but aim your strokes at him! This is my command—come what will, be the fortune of war what it may, who ever conquers or loses, lives or dies—kill Bohemund!”

The emperor’s voice rang vibrantly in the chamber, his dark eyes flashed magnetically. Roger felt the force of the man’s dynamic personality like a physical impact.

“The Crusaders have already been a few days on the road,” said Alexis, “but they travel slowly, for their cavalry must keep pace with their wagons. It will be easy for you to pass beyond them and reach the Sultan before he joins battle, with the arrangements I have made. Your steed is already on a boat—a fresh steed, that is. The boat lies at the root of the Green Pier—but Angelus will guide you thither. On the Asiatic side Ortuk Khan, he whom men call the Rider of the Wind, will meet you and lead you to the Sultan. Theodore Butumites is with Godfrey—” he broke off suddenly, staring at Roger’s coif. “By Saint Paul,” said he, “there is fresh blood on your mail, Thorvald. Are you wounded?”

His mind full of whirling conjectures, Roger absently answered, “No.”

Instantly he was realized his mistake. Alexis started, and his keen eyes flared with suspicion. Every faculty of the man was as sharp as a whetted sword.

“That’s not Thorvald’s voice!” he snarled, and with a motion quick as a striking hawk, he ripped the scarf from the knight’s head. Both men leaped to their feet, the emperor recoiling with a scream.

“Spy! This is not Thorvald! Ho, the guard!”

Sir Roger’s sword flashed in the candle-light. Alexis leaped back, catlike, and the blade sheared a lock of hair from his head as it hummed past. Instantly it seemed, the room swarmed with armed men, pouring in from each door. But the sight of the emperor fleeing desperately from the murderous attack of one they supposed to be a loyal servitor momentarily froze their wits. Roger alone knew exactly what he had to do. No time for another stroke at the emperor who had sprung behind the great chair, and was shouting for his soldiers to cut down the impostor. The Norman wheeled toward the nearest door, where three men barred his way. The first went down, casque and skull cloven by the knight’s shearing stroke, and as the other two sprang in hacking, Sir Roger ducked and drove in headlong behind his shield. They reeled apart before the impact, and the Norman’s bull-like drive carried him through the door and into the corridor. Recovering his balance in full flight, he raced down the short hallway. The outer door had been left unguarded. A quick fumbling at the chains and bolts and he was through, slammed the door in the faces of his yelling pursuers, and fled down the narrow street, cursing the clang of his mail-shod feet on the flags. He could not hope to evade his attackers, but ahead of him were the broad rows of green marble steps leading down to the water’s edge, known as the Green Pier. He knew it of old. At the foot of the steps lay a broad boat, the steersman holding the craft to the lower step by a boat-hook thrust into a ring set in the marble. A rangy Arab horse was held quiet by grooms and the brawny oarsmen gaped at his haste, as the knight ran down the steps and sprang into the boat.

“Give way!” he growled. The boatmen hesitated. Up the street came the clamor of pursuit. Steel clanked and torches tossed.

“Push off!” the boatmen saw the glimmer of naked steel in the knight’s mailed hand. They were unarmed laborers, not fighters. The steersman disengaged the boathook, and thrusting it against the steps, shoved powerfully. The heavy craft swung out into the current, and the rowers bent to their labor. They moved out into the shadowy star-mirroring reaches, and looking back, Sir Roger saw mailed figures racing up and down the piers, seeking a boat. But luck was with him; the wharfs had vanished in the distance before he heard faintly the clack of oar-locks, and knew that the pursuit had taken to water.

The rowers, eyeing his dripping sword, bent to their oars as strongly as if he had been Alexis himself. The noise of the pursing boats drew steadily nearer; they dogged his trail throughout that three-mile row, and the last few hundred yards he saw starlight glinting on helmets. But he was still a few score paces ahead when the low prow nudged the Asian shore. Springing to the saddle, he spurred the steed over the side, and plunged into the darkness.

There he had the advantage. His pursuers were not mounted, although it was quite possible that there might be steeds for them in the vicinity. He headed eastward at a long swinging gallop. In the darkness he was aware only of a vague shadowy landscape of low hills and flat stretches, with occasional blurs he took to be herders’ huts. Clouds had again obscured the stars, and the moon had long set. He drew rein, moving along almost at a walk, in the thick darkness, when suddenly he realized that there was a movement about him. He heard the restive stamp of hoofs, and the jingle of trappings. A voice swore in a tongue alien yet hatefully familiar. Turks! He had ridden blindly into them in the darkness. They were all about him, hemming him in. Stealthily he reached for his sword, then a sibilant voice inquired, “Is it you, lord Thorvald?”

“Who else?” growled the knight, striving to assume the harsh accents of the Norseman.

“Strike a light,” muttered another voice. “Best be certain.”

There was the clink of flint on steel, and a tiny flame sprang up, illuminating a ring of bearded hawk-like faces—glinting on polished shoulderplates, burnished helmets and ring-mail. The tall warrior who held the light leaned forward and eyed Sir Roger intently.

“There is the gold falcon, see?” said the Moslem. “Besides, look at the sword. The face of the Smiter is not so familiar to me that I would know it without the beard, but by Allah, I would recognize that blade anywhere!”

The light went out. Behind them, toward the shore, came a distant murmur as of many men. Torches tossed erratically. Roger felt the warriors about him stiffen suspiciously, and he heard the stir of scimitars in their sheaths.

“Who moves yonder?” asked the tall Moslem.

“Men the emperor sent to see that I got safely across,” answered Sir Roger. “He feared lest the Franks had left spies behind them. Why do we linger here? It is not long until dawn.”

“True,” muttered the Turk. “And we were better safe in the hills before daylight. You came ahead of time. We were riding to the shore to meet you, when you rode in among us.We were lucky that we did not miss each other in this accursed dark. Ride in the midst of us, my lord.”

They moved off in a canter that grew into an easy swinging gallop that ate up the miles. As dawn rose, the band, like a flying band of desert ghosts, crossed the shoulder of a blue mountain and vanished in the hills beyond.

Daylight showed the knight his companions—a score of hawk-like riders in the steel and gold and leather of the Seljuks. They rode like the wind, like men who do not have to spare their mounts, and he guessed that relays awaited them in the hills—for already they were beyond the eastern-most bounds of Alexis’ domain. They had not suspected him, and in that grim masquerade he had made no plans. He had but followed the trend of the tide, caught in the eddy, moving without volition of his own. He knew what he would do if the opportunity rose, but for the moment he was helpless, with only half-facts at his command.

Indeed, the whole course of his life had lain along those lines, he thought morosely, to the tune of the drumming hoofs. Born in castle built up out of the ruins of a Saxon keep, almost exactly a year after the Battle of Hastings, Sir Roger’s impulses and instincts had led him into such a tangle of affairs that he himself despaired of unravelling it. So, he departed from the land of his birth, not much in advance of soldiers sent by the exasperated king. Resentment toward his liege led him into the service of Duke Robert of Normandy, who was continually at logger-heads with his fox-like brother, but Roger’s impatient spirit could not endure the procrastinating and wine-guzzling habits of the Duke, however generous and good-natured, and presently he found himself in the kingdom Norman swords had carved in southern Italy. He had ridden beside Tancred and shared the yellow fighting-cock’s adventures, but Bohemund’s everlasting ambition had palled on the English knight. The scene shifted to the Rhineland, where he was a participant in the gory climax of Duke Godfrey’s feud with Rudolph of Swabia. Then came the dawn of the Crusades, Urban’s trumpet-like invocation, and men selling their lands to buy horses to carry them eastward to salvation and the slaughter of the heathen.

The barons were gathering, but to the more penniless, they moved too slowly. Besides, there was an unexpressed doubt that there would be enough plunder to go around, once the great lords took the field. A horde of ploughmen, beggars and vagabonds rallied around Peter the Hermit, kissing the ground on which he walked, and getting their brains kicked out by his pessimistic jackass when they tried to pluck out the animal’s grey hairs for holy relics. Peter emulated Urban and great was his magnetic power. To the gaunt fanatic likewise came a sprinkling of poverty-ridden knights and nobles, and the motley horde moved eastward down the Danube, singing hosannas and stealing pigs.

Among these poverty-ridden knights were Roger de Cogan and his brother-at-arms, Gautier sans Avoir—the Penniless. They tried to herd the horde, but they might as well have tried to herd the vultures of the Carpathians. The ravenous pilgrims, some eighty thousand strong, passed like a famine through the land of the Hungarians, fought with Alexis’ outpost, fell on their knees to greet the spires of Constantinople, and settled themselves down, apparently, to devour all the food in the empire.

When they began to hack sheets of lead from the cathedral roofs to sell in the market place, Alexis, in despair, had them ferried across the Bosphorus, and there herds of them straggled away into the hills and managed to get themselves butchered by a raiding band of Turks. Gautier and his comrades, with more valor than discretion, sallied forth to rescue the miserable wretches, and ran into a veritable army of chanting heron-feathered riders. There died Gautier, on a heap of Turkish corpses, with his mad and gallant gentlemen, and Sir Roger, recovering his senses after a battle-axe, shattering on his casque, had dashed him into darkness, found himself bound with chains along with the remnant of his band, and being marched to Nicea, where he was sold to a tall lean vulture in steel and gold—the Arab Yusef ibn Zalim. His lean ship cruised the shores of the Black Sea, and up and down the Bosphorus from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and Roger saw sights both in the belly of the galley, and on the blood-stained deck, which haunted his dreams for the rest of his life. Yet these red visions were not able to dim one scene of horror and madness—his comrade Gautier, dying among the dead, and a lean scornful horseman in gilded mail and heron-feathered helmet, rearing his horse to bring down the hoofs crashing in the blood-stained dying face.

“Thus Othman, son of Kilidg Arslan, deals with infidels!” The scornful words ran in Roger de Cogan’s ears above the wash of waves, the splintering of the oars, and the red clamor of battle.

Now the English knight found himself galloping in company with Turkish reavers, in a grim masquerade, bound for a destination of which he knew nothing, save that it would doubtless bring him face to face with Prince Othman and his grim sire. He kept looking back for signs of pursuit; but if Alexis’ soldiers had followed, they had missed the trail.

At noon the riders came upon a squat tower in the hills, where food and drink and fresh horses awaited them. They were in the outlying domain of Kilidg Arslan, the Red Lion of Islam, but as yet they had seen no villages, and only ruins, relics of ancient Roman rule. They spent scant time at their meal, but swung to the saddle and spurred up their mounts again.

And all through the hot dry summer afternoon they swung through the rugged hills at a gallop, pushing their horses unmercifully. Roger had kept his eyes open for out-riders of the Crusaders, or signs of their march, but he realized that they must be riding to the north of the Cross Wearers’ line of march. He asked no questions, nor did Ortuk Khan vouch-safe any information; he rode along humming a song about a warrior whose skill at racing had gained for him the name of the Rider of the Wind. Roger sensed that this matter was the Seljuk’s one weakness and vanity.

At moonrise, and again when the moon had set, they came again upon a relay of fresh horses in the hills, with a dusty courier, with whom Ortuk Khan talked long. Then he seated himself cross-legged on the ground, and signed for the men to prepare the meal.

“We are within striking distance of our objective,” said he to Roger. “We have covered in hours what took the Cross Wearers days to traverse. We are now but three hours’ riding from the camp of the infidels. At dawn we will go forward, and join in the battle.”

Roger had been puzzling in his mind as to how Alexis meant to wipe out Bohemund without destroying the rest of the Crusaders, and he ventured a question. “Repeat to me the trap the Red Lion has set for the Cross Wearers.”

“Thus it is,” answered Ortuk Khan readily. “Maimoun—Bohemund—and his people march ahead of the main body of the infidels. This night they lie in camp where the hills slope down into the plain of Doryleum, awaiting the coming up of Senjhil—St. Gilles—and the rest.

“But Alexis has given these others a guide to lead them astray. You see yonder peak which stands up in the moonlight above the other hills? Were you to ride due south on a straight line from that peak for five hours, you would come upon their camp.

“At dawn, the Red Lion will ride in from the east, and crush Maimoun and his iron men between his hands. Then he will move on Senjhil and the others and sweep them from the earth.”

So Alexis was hand-and-glove with the Seljuk, as far as destroying Bohemund went; it had been obvious from the beginning. The traitorous guide mentioned by Ortuk Khan must be Theodore Butumites. Alexis had said the Greek was with St. Gilles. Roger looked long at the peak pointed out to him by the Turk, and fixed the land marks of the country firmly in his mind. Doryleum was three hours ride to the east; the camp of the others five hours’ ride to the south. On the eastern hills was crawling the first faint whitening of dawn. The Turks were bestirring themselves, saddling their horses and buckling their armor.

“Ortuk Khan,” said Sir Roger casually, rising and laying his hand on the mane of the lean Turkoman steed which had been given him, “dawn is lifting and we must quickly be on our way to join the Red Lion. But to breathe our steeds, I will race you to yonder knoll.”

The Turk smiled. “It is still three hours’ hard riding to Doryleum, my lord, and out steeds will have much work to do after we reach the field.”

“It is only a few hundred paces to the knoll,” answered Sir Roger. “I have heard much of your skill at racing, and wished to have the honor of striving against you. Of course, there are many stones and boulders, and the footing is perilous. If you fear the attempt—”

Ortuk Khan’s face darkened.

“That was ill said, oh man men call the Smiter. The folly of one makes fools of wise men. Yet mount, and I will do this childish thing.”

They swung to their saddles, reined back their mounts even with each other, then at a word were off like bolts from a crossbow. The steel-clad warriors watched the race with interest.

“The footing is not so unstable as the Frank said,” quoth one. “Look, their flight is as that of falcons. Ortuk Khan draws ahead.”

“But the Smiter is close on his heels!” exclaimed another. “Look, they near the knoll—what is this? The Frank has drawn his sword! It flashes in the dawn-light—Allah!”

A yell of astounded fury rose from the lean warriors. Riding hard, the Norman had disappeared around the knoll; behind him a riderless horse raced away from the still form which lay in a crimson pool among the rocks. The Rider of the Wind had ridden his last race.

Shaking the red drops from his blade, Sir Roger gave the Turkoman horse the rein. He did not look back, though he strained his ears for the drum of pursuing hoofs. Guiding his course by the peak, he passed through the hills like a flying ghost. A short time after sunrise he crossed a broad track, with marks of broad wagon-wheels and the print of myriad feet and hoofs. The road of Bohemund. Among these prints were fresher hoof-prints, unshod, smaller. The prints of Turkish steeds. So the scouts of the Seljuks dogged the Norman column closely.

It was past the middle of the morning when Roger rode into the vast wide-flung camp of the Crusaders. His none too tender heart warmed at the familiar sights—knights with falcons on their wrists and giant hounds trailing them; yellow-haired women laughing under canopied pavilions; young esquires burnishing the armor of their lords. It was like a bit of Europe transferred to the bleak hills of Asia Minor. Two hundred thousand people camped here, their fires and tents spreading out over the valley. Some of the pavilions had been taken down, some of the oxen harnessed to the wagons, but there was an air of waiting. Men-at-arms leaned on their pikes, pages wandered through the low bushes, whistling to their hounds. It was as if all the west had streamed eastward. Roger saw flaxen-haired Rhinelanders, black-bearded Spaniards and Provençals—French, Germans, Austrians. The clatter of a score of different tongues reached him.

The English knight reined through the throngs which stared at his dusty mail and sweaty horse, and halted before the pavilions whose richer colors betokened the leaders of the expedition. He saw them coming forth from their tents in full armor—Godfrey of Bouillon, and his brothers, Eustace and Baldwin of Boulogne—a stocky grey-bearded figure which must be Raymond of St. Gilles, Count of Toulouse. With them was a figure in ornate armor, the burnished plates contrasting with the grey mesh-mail coats of the westerners—Roger knew the man must be Theodore Butumites, brother of the new-made duke of Nicea and officer of the Greek cataphracts.

The Turkoman charger snorted and tossed its head up and down, froth flying from the bit, as Roger slid to earth. Norman-like, the knight wasted no words.

“My lords,” he said bluntly, without preliminary salutation, “I have come to tell you that a battle is forward, and if you would take part, you had best hasten.”

“A battle?” It was Eustace of Boulogne, keen as a hunting hound on the scent. “Who fights?”

“Bohemund confronts the Red Lion, even as we stand here.”

The barons looked at each other uncertainly and Butumites laughed.

“The man is mad. How could Kilidg Arslan fall upon Bohemund without passing us? And we have seen no Turks.”

“Where is Bohemund?” asked Raymond.

“In the plain of Doryleum, some six hours hard riding to the north.”

“What!” It was an exclamation of unbelief. “How could that be? The lord Theodore has led us in a direct route, through valleys Bohemund missed. The Normans are somewhere behind us, and Theodore has sent his Byzantine scouts to find them and bring them hither, since it is evident that they have become lost in the hills. We are awaiting them before we take up the march.”

“It is you who are lost,” snapped Sir Roger. “Theodore Butumites is a spy and a traitor, sent by Alexis to lead you astray, while Kilidg Arslan crushes Bohemund—”

“Dog, your life for that!” shouted the fiery Greek, striding forward, his hand on his sword. Roger fronted him grimly, gripping his own hilt, but the barons intervened.

“These are serious accusations you bring, friend,” said Godfrey. “What proofs have you of these words?”

“Why, in God’s name,” exclaimed Roger, “have you not seen that the Greek has swung further and further south? The Normans took the straighter course—it is you who have wandered from the route. Bohemund marched southeast by south—you have traveled due south. If you follow this course long enough, you may fetch the Mediterranean, but you will scarce come to the Holy Land!”

“Who is this rogue?” exclaimed Butumites angrily.

“Duke Godfrey knows me,” retorted the Norman. “I am Roger de Cogan.”

“By the saints!” exclaimed Godfrey, a smile lighting his worn face. “I had thought to recognize you, Roger! But you have changed—you have changed. My lords,” he turned to the others, “this gentleman is known to me aforetime—nay, he rode with me into the Lateran, when I—”

He checked himself with the strange aversion he always felt toward speaking of what he considered his sacrilege in killing Duke Rudolph in the holy confines.

“But we know him not,” answered St. Gilles, with the caution that always ate at him like a worm in a beam. “And he comes with a strange tale—he would lead us on a wild chase, with naught but his own word—”

“God’s thunder!” cried Roger, his short Norman patience exhausted. “Shall we gabble here while the Turks cut Bohemund’s throat? It is my word against the Greek’s, and I demand trial—the gauge of combat to decide between us!”

“Well spoken!” exclaimed Adhemar, the pope’s legate, a tall man who wore the chain mail of a knight, and was a warrior at heart. Such scenes warmed his heart, which was that of a warrior. “As mouth-piece of our Holy Father, I declare the righteousness of such course.”

“Well, and let us be at it!” exclaimed Roger, burning with impatience. “Choose your weapons, Greek!”

Butumites glanced over his dusty mail, and the light-limbed, sweat-covered steed, and smiled secretly.

“Dare you run a course with sharpened spears?”

This was a matter at which the Franks were more experienced than the Greeks, but Butumites was of larger boned frame than most of his race, well able to compete with the westerners in physical strength, and he had had experience, jousting with the western knights while they lay at Alexis’ court. He glanced at his giant black war-horse, accoutered with heavy trappings of silk, steel and lacquered leather, and smiled again. But Godfrey interposed.

“Nay, masters, this is but a sorry thing, seeing that Sir Roger has come hither on a weary steed, and that more fit for racing than fighting. Nay, Roger, you shall take my steed and lance, and my casque, too.”

Butumites shrugged his shoulders. In an instant his crushing advantage had been swept away, but he was still confident. At any rate, he preferred lances to sword-strokes, having no desire to encounter the stroke of the great sword that hung at Roger’s hip. He had fought Normans before.

Roger took the long heavy spear, and mounted the steed, held by Godfrey’s esquires, but refused the heavy helmet—a massive pot-like affair, without a movable vizor, but with a slit for the eyes. The joust had not then attained its later conventions and formalities; at that early date a lance-running was either a duel with sharpened weapons, or simply a form of training for more serious war-fare. A rude course had been formed by the crowd, pressing in on both sides, leaving a broad lane open. In this clear space the foes trotted apart for a short distance, wheeled, couched their lances, and awaited the signal.

The trumpet blared and the great horses thundered toward each other. The shining black armor and plumed casque of the Byzantine contrasted strongly with the dusty grey armor and plain iron bassinet of the Norman. Roger knew that Butumites would aim his lance directly at his unprotected face, and he bent low, glaring at his foe above the upper rim of his heavy shield. The hosts gave tongue as the knights shocked together with a rending crash. Both lances shivered to the hand-grips, and the horses were hurled back on their haunches. But Roger kept his seat, though half-stunned by the terrible impact, while Butumites was dashed from his saddle as though by a thunder-bolt. He lay where he had fallen, his burnished steel-clad limbs crumpled in the dust, blood oozing from his cracked helmet.

Roger reined in his rearing steed and slid to earth dazedly, his head still ringing. The breaking lance of the Byzantine, glancing from the rim of his shield, had torn his bassinet from his head, and all but ripped loose the tendons of his neck. He advanced rather stiffly to the group which had formed about the prostrate Greek. The casque with its nodding plumes had been lifted off, and Butumites looked up at the faces above him with glazed eyes. It was evident that the man was dying. His breast-plate was shattered, and his whole breastbone caved inward. Adhemar leaned above him, rosary in hand, muttering rapidly.

“My son, have you any confession?”

The dying lips worked, but only a dry rattle came from them. With a terrible effort the Greek muttered, “Doryleum—Kilidg Arslan—Bohemund—” blood gushed from his lips, and he stiffened, a still figure of burnished metal, steel-sheathed limbs falling awry.

Godfrey went into instant action.

“To horse!” he shouted. “A steed for Sir Roger! Bohemund needs aid and by the favor of God, he shall not call in vain!”

The throng yelped and the scene became a medley of confusion, knights mounting, men-at-arms buckling on their armor.

“Wait!” exclaimed St. Gilles. “We can not go racing over these hills, wagons and footmen—some one must guard the supplies—”

“Do you this thing, my lord Raymond,” said Godfrey, a-fire with impatience. “Get the wagons under way, and follow with them and the footmen. My horsemen and I will push forward. Roger, lead the way!”