Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

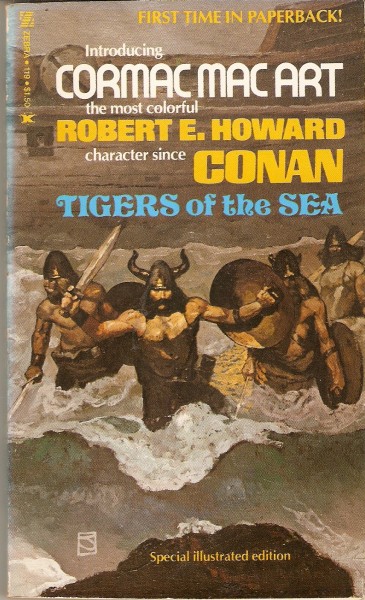

Published in Tigers of the Sea, 1974.

| I. II. |

III. IV. |

V. VI. |

“Tigers of the sea! Men with the hearts of wolves and thews of fire and steel! Feeders of ravens whose only joy lies in slaying and dying! Giants to whom the death-song of the sword is sweeter than the love-song of a girl!”

The tired eyes of King Gerinth were shadowed.

“This is no new tale to me; for a score of years such men have assailed my people like hunger-maddened wolves.”

“Take a page from Caesar’s book,” answered Donal the minstrel as he lifted a wine goblet and drank deep. “Have we not read in the Roman books how he pitted wolf against wolf? Aye—that way he conquered our ancestors, who in their day were wolves also.”

“And now they are more like sheep,” murmured the king, a quiet bitterness in his voice. “In the years of the peace of Rome, our people forgot the arts of war. Now Rome has fallen and we fight for our lives—and cannot even protect our women.”

Donal set down the goblet and leaned across the finely carved oak table.

“Wolf against wolf!” he cried. “You have told me—as well I knew!—that no warriors could be spared from the borders to search for your sister, the princess Helen—even if you knew where she is to be found. Therefore, you must enlist the aid of other men—and these men I have just described to you are as superior in ferocity and barbarity to the savage Angles that assail us as the Angles themselves are superior to our softened peasantry.”

“But would they serve under a Briton against their own blood?” demurred the king. “And would they keep faith with me?”

“They hate each other as much as we hate them both,” answered the minstrel. “Moreover, you can promise them the reward—only when they return with the princess Helen.”

“Tell me more of them,” requested King Gerinth.

“Wulfhere the Skull-splitter, the chieftain, is a red-bearded giant like all his race. He is crafty in his way, but leads his Vikings mainly because of his fury in battle. He handles his heavy, long shafted axe as lightly as if it were a toy, and with it he shatters the swords, shields, helmets and skulls of all who oppose him. When Wulfhere crashes through the ranks, stained with blood, his crimson beard bristling and his terrible eyes blazing and his great axe clotted with blood and brains, few there are who dare face him.

“But it is on his righthand man that Wulfhere depends for advice and council. That one is crafty as a serpent and is known to us Britons of old—for he is no Viking at all by birth, but a Gael of Erin, by name Cormac Mac Art, called an Cliuin, or the Wolf. Of old he led a band of Irish reivers and harried the coasts of the British Isles and Gaul and Spain—aye, and he preyed also on the Vikings themselves, But civil war broke up his band and he joined the forces of Wulfhere—they are Danes and dwell in a land south of the people who are called Norsemen.

“Cormac Mac Art has all the guile and reckless valor of his race. He is tall and rangy, a tiger where Wulfhere is a wild bull. His weapon is the sword, and his skill is incredible. The Vikings rely little on the art of fencing; their manner of fighting is to deliver mighty blows with the full sweep of their arms. Well, the Gael can deal a full arm blow with the best of them, but he favors the point. In a world where the old-time skill of the Roman swordsman is almost forgotten, Cormac Mac Art is well-nigh invincible. He is cool and deadly as the wolf for which he is named, yet at times, in the fury of battle, a madness comes upon him that transcends the frenzy of the Berserk. At such times he is more terrible than Wulfhere, and men who would face the Dane flee before the blood-lust of the Gael.”

King Gerinth nodded. “And could you find these men for me?”

“Lord King, even now they are within reach. In a lonely bay on the western coast, in a little-frequented region, they have beached their dragon-ship and are making sure that it is fully sea-worthy before moving against the Angles. Wulfhere is no sea-king; he has but one ship—but so swiftly he moves and so fierce is his crew that the Angles, Jutes and Saxons fear him more than any of their other foes. He revels in battle. He will do as you wish him, if the reward is great enough.”

“Promise him anything you will, answered Gerinth. “It is more than a princess of the realm that has been stolen—it is my little sister.”

His fine, deeply-lined face was strangely tender as he spoke.

“Let me attend to it,” said Donal, refilling his goblet. “I know where these Vikings are to be found. I can pass among them—but I tell you before I start that it will take your Majesty’s word, from your own lips, to convince Cormac Mac Art of—anything! Those Western Celts are more wary than the Vikings themselves.”

Again King Gerinth nodded. He knew that the minstrel had walked strange paths and that though he was loquacious on most subjects, he was tight-lipped on others. Donal was blest or cursed with a strange and roving mind and his skill with the harp, opened many doors to him that axes could not open. Where a warrior had died, Donal of the Harp walked unscathed. He knew well many fierce sea-kings who were but grim legends and myths to most of the people of Britain, but Gerinth had never had cause to doubt the minstrel’s loyalty.

Wulfhere of the Danes fingered his crimson beard and scowled abstractedly. He was a giant; his breast muscles bulged like twin shields under his scale mail corselet. The horned helmet on his head added to his great height, and with his huge hand knotted about the long shaft of a great axe he made a picture of rampant barbarism not easily forgotten. But for all his evident savagery, the chief of the Danes seemed slightly bewildered and undecided. He turned and growled a question to a man who sat near.

This man was tall and rangy. He was big and powerful, and though he lacked the massive bulk of the Dane, he more than made up for it by the tigerish litheness that was apparent in his every move. He was dark, with a smooth-shaven face and square-cut black hair. He wore none of the golden armlets or ornaments of which the Vikings were so fond. His mail was of chain mesh and his helmet, which lay beside him, was crested with flowing horse-hair.

“Well, Cormac,” growled the pirate chief, “what think you?”

Cormac Mac Art did not reply directly to his friend. His cold, narrow, grey eyes gazed full into the blue eyes of Donal the minstrel. Donal was a thin man of more than medium height. His wayward unruly hair was yellow. Now he bore neither harp nor sword and his dress was whimsically reminiscent of a court jester. His thin, patrician face was as inscrutable at the moment as the sinister, scarred features of the Gael.

“I trust you as much as I trust any man,” said Cormac, “but I must have more than your mere word on the matter. How do I know that this is not some trick to send us on a wild goose chase, or mayhap into a nest of our enemies? We have business on the east coast of Britain—”

“The matter of which I speak will pay you better than the looting of some pirate’s den,” answered the minstrel. “If you will come with me, I will bring you to the man who may be able to convince you. But you must come alone, you and Wulfhere.”

“A trap,” grumbled the Dane. “Donal, I am disappointed in you—”

Cormac, looking deep into the minstrel’s strange eyes, shook his head slowly.

“No, Wulfhere; if it be a trap, Donal too is duped and that I cannot believe.”

“If you believe that,” said Donal, “why can you not believe my mere word in regard to the other matter?”

“That is different,” answered the reiver. “Here only my life and Wulfhere’s is involved. The other concerns every member of our crew. It is my duty to them to require every proof. I do not think you lie; but you may have been lied to.”

“Come, then, and I will bring you to one whom you will believe in spite of yourself.”

Cormac rose from the great rock whereon he had been sitting and donned his helmet. Wulfhere, still grumbling and shaking his head, shouted an order to the Vikings who sat grouped about a small fire a short distance away, cooking a haunch of venison. Others were tossing dice in the sand, and others still working on the dragonship which was drawn up on the beach. Thick forest grew close about this cove, and that fact, coupled with the wild nature of the region, made it an ideal place for a pirate’s rendezvous.

“All sea-worthy and ship-shape,” grumbled Wulfhere, referring to the galley. “On the morrow we could have sailed forth on the Viking path again—”

“Be at ease, Wulfhere,” advised the Gael. “If Donal’s man does not make matters sufficiently clear for our satisfaction, we have but to return and take the path.”

“Aye—if we return.”

“Why, Donal knew of our presence. Had he wished to betray us, he could have led a troop of Gerinth’s horsemen upon us, or surrounded us with British bowmen. Donal, at least, I think, means to deal squarely with us, as he has done in the past. It is the man behind Donal I mistrust.”

The three had left the small bay behind them and now walked along in the shadow of the forest. The land tilted upward rapidly and soon the forest thinned out to straggling clumps and single gnarled oaks that grew between and among huge boulders—boulders broken as if in a Titan’s play. The landscape was rugged and wild in the extreme. Then at last they rounded a cliff and saw a tall man, wrapped in a purple cloak, standing beneath a mountain oak. He was alone and Donal walked quickly toward him, beckoning his companions to follow. Cormac showed no sign of what he thought, but Wulfhere growled in his beard as he gripped the shaft of his axe and glanced suspiciously on all sides, as if expecting a horde of swordsmen to burst out of ambush. The three stopped before the silent man and Donal doffed his feathered cap. The man dropped his cloak and Cormac gave a low exclamation.

“By the blood of the gods! King Gerinth himself!”

He made no movement to kneel or to uncover his head, nor did Wulfhere. These wild rovers of the sea acknowledged the rule of no king. Their attitude was the respect accorded a fellow warrior; that was all. There was neither insolence nor deference in their manner, though Wulfhere’s eyes did widen slightly as he gazed at the man whose keen brain and matchless valor had for years, and against terrific odds, stemmed the triumphant march of the Saxons to the Western sea.

The Dane saw a tall, slender man with a weary aristocratic face and kindly grey eyes. Only in his black hair was the Latin strain in his veins evident. Behind him lay the ages of a civilization now crumbled to the dust before the onstriding barbarians. He represented the last far-flung remnant of Rome’s once mighty empire, struggling on the waves of barbarism which had engulfed the rest of that empire in one red inundation.

Cormac, while possessing the true Gaelic antipathy for his Cymric kin in general, sensed the pathos and valor of this brave, vain struggle, and even Wulfhere, looking into the far-seeing eyes of the British king, felt a trifle awed. Here was a people, with their back to the wall, fighting grimly for their lives and at the same time vainly endeavoring to uphold the culture and ideals of an age already gone forever. ‘The gods of Rome had faded under the ruthless heel of Goth and Vandal. Flaxen-haired savages reigned in the purple halls of the vanished Caesars. Only in this far-flung isle a little band of Romanized Celts clung to the traditions of yesterday.

“These are the warriors, your Majesty,” said Donal, and Gerinth nodded and thanked him with the quiet courtesy of a born nobleman.

“They wish to hear again from your lips what I have told them,” said the bard.

“My friends,” said the king quietly, “I come to ask your aid. My sister, the princess Helen, a girl of twenty years of age, has been stolen—how, or by whom, I do not know. She rode into the forest one morning attended only by her maid and a page, and she did not return. It was on one of those rare occasions when our coasts were peaceful; but when search parties were sent out, they found the page dead and horribly mangled in a small glade deep in the forest. The horses were found later, wandering loose, but of the princess Helen and her maid there was no trace. Nor was there ever a trace found of her, though we combed the kingdom from border to sea. Spies sent among the Angles and Saxons found no sign of her, and we at last decided that she had been taken captive and borne away by some wandering band of sea-farers who, roaming inland, had seized her and then taken to sea again.

“We are helpless to carry on such a search as must be necessary if she is to be found. We have no ships—the last remnant of the British fleet was destroyed in the sea-fight off Cornwall by the Saxons. And if we had ships, we could not spare the men to man them, not even for the princess Helen. The Angles press hard on our eastern borders and Cerdic’s brood raven upon us from the south. In my extremity I appeal to you. I cannot tell you where to look for my sister. I cannot tell you how to recover her if found. I can only say: in the name of God, search the ends of the world for her, and if you find her, return with her and name your price.”

Wulfhere glanced at Cormac as he always did in matters that required thought.

“Better that we set a price before we go,” grunted the Gael.

“Then you agree?” cried the king, his fine face lighting.

“Not so fast,” returned the wary Gael. “Let us first bargain. It is no easy task you set us: to comb the seas for a girl of whom nothing is known save that she was stolen. How if we search the oceans and return empty-handed?”

“Still I will reward you,” answered the king. “I have gold in plenty. Would I could trade it for warriors—but I have Vortigern’s example before me.”

“If we go and bring back the princess, alive or dead,” said Cormac, “you shall give us a hundred pounds of virgin gold, and ten pounds of gold for each man we lose on the voyage. If we do our best and cannot find the princess, you shall still give us ten pounds for every man slain in the search, but we will waive further reward. We are not Saxons, to haggle over money. Moreover, in either event you will allow us to overhaul our long ship in one of your bays, and furnish us with material enough to replace such equipment as may be damaged during the voyage. Is it agreed?”

“You have my word and my hand on it,” answered the king, stretching out his arm, and as their hands met Cormac felt the nervous strength in the Briton’s fingers.

“You sail at once?”

“As soon as we can return to the cove.”

“I will accompany you,” said Donal suddenly, “and there is another who would come also.”

He whistled abruptly—and came nearer to sudden decapitation than he guessed; the sound was too much like a signal of attack to leave the wolf-like nerves of the sea-farers untouched. Cormac and Wulfhere, however, relaxed as a single man strode from the forest.

“This is Marcus, of a noble British house,” said Donal, “the betrothed of the princess Helen. He too will accompany us if he may.”

The young man was above medium height and well built. He was in full chain mail armor and wore the crested helmet of a legionary; a straight thrusting-sword was girt upon him. His eyes were grey, but his black hair and the faint olive-brown tint of his complexion showed that the warm blood of the South ran far more strongly in his veins than in those of his king. He was undeniably handsome, though now his face was shadowed with worry.

“I pray you will allow me to accompany you.” He addressed himself to Wulfhere. “The game of war is not unknown to me—and waiting here in ignorance of the fate of my promised bride would be worse to me than death.”

“Come if you will,” growled Wulfhere. “It’s like we’ll need all the swords we can muster before the cruise is over. King Gerinth, have you no hint whatever of who took the princess?”

“None. We found only a single trace of anything out of the ordinary in the forests. Here it is.”

The king drew from his garments a tiny object and passed it to the chieftain. Wulfhere stared, unenlightened, at the small, polished flint arrowhead which lay in his huge palm. Cormac took it and looked closely at it. His face was inscrutable but his cold eyes flickered momentarily. Then the Gael said a strange thing:

“I will not shave today, after all.”

The fresh wind filled the sails of the dragonship and the rhythmic clack of many oars answered the deep-chested chant of the rowers. Cormac Mac Art, in full armor, the horse-hair of his helmet floating in the breeze, leaned on the rail of the poop-deck. Wulfhere banged his axe on the deal planking and roared an unnecessary order at the steersman.

“Cormac,” said the huge Viking, “who is king of Britain?”

“Who is king of Hades when Pluto is away?” asked the Gael.

“Read me no runes from your knowledge of Roman myths,” growled Wulfhere.

“Rome ruled Britain as Pluto rules Hades,” answered Cormac. “Now Rome has fallen and the lesser demons are battling among themselves for mastery. Some eighty years ago the legions were withdrawn from Britain when Alaric and his Goths sacked the imperial city. Vortigern, was king of Britain—or rather, made himself so when the Britons had to look to themselves for aid. He let the wolves in, himself, when he hired Hengist and Horsa and their Jutes to fight off the Picts, as you know. The Saxons and Angles poured in after them like a red wave and Vortigern fell. Britain is split into three Celtic kingdoms now, with the pirates holding all the eastern coast and slowly but surely forcing their way westward. The southern kingdom, Damnonia and the country extending to Caer Odun, is ruled over by Uther Pendragon. The middle kingdom, from Uther’s lines to the foot of the Cumbrian Mountains, is held by Gerinth. North of his kingdom is the realm known by the Britons as Strath-Clyde—King Garth’s domain. His people are the wildest of all the Britons, for many of them are tribes which were never fully conquered by Rome. Also, in the most westwardly tip of Damnonia and among the western mountains of Gerinth’s land are barbaric tribes who never acknowledged Rome and do not now acknowledge any one of the three kings. The whole land is prey to robbers and bandits, and the three kings are not always at peace among themselves, owing to Uther’s waywardness, which is tinged with madness, and to Garth’s innate savagery. Were it not that Gerinth acts as a buffer between them, they would have been at each other’s throats long ago.

“As it is they seldom act in concert for long. The Jutes, Angles and Saxons who assail them are forever at war among themselves also, as you know, but a never-ending supply streams across the Narrow Seas in their long, low galleys.”

“That too I well know,” growled the Dane, “having sent some score of those galleys to Midgaard. Some day my own people will come and take Britain from them.”

“It is a land worth fighting for,” responded the Gael. “What think you of the men we have shipped aboard?”

“Donal we know of old. He can tear the heart from my breast with his harp when he is so minded, or make me a boy again. And in a pinch we know he can wield a sword. As for the Roman—” so Wulfhere termed Marcus, “he has the look of a seasoned warrior.”

“His ancestors were commanders of British legions for three centuries, and before that they trod the battlefields of Gaul and Italy with Caesar. It is but the remnant of Roman strategy lingering in the British knights that has enabled them to beat back the Saxons thus far. But, Wulfhere, what think you of my beard?” The Gael rubbed the bristly stubble that covered his face.

“I never saw you so unkempt before,” grunted the Dane, “save when we had fled or fought for days so you could not be hacking at your face with a razor.”

“It will hide my scars in a few days,” grinned Cormac. “When I told you to head for Ara in Dalriadia, did naught occur to you?”

“Why, I assumed you would ask for news of the princess among the wild Scots there.”

“And why did you suppose I would expect them to know?”

Wulfhere shrugged his shoulders. “I am done seeking to reason out your actions.”

Cormac drew from his pouch the flint arrowhead. “In all the British Isles there is but one race who makes such points for their arrows. They are the Picts of Caledonia, who ruled these isles before the Celts came, in the age of stone. Even now they tip their arrows often with flint, as I learned when I fought under King Gol of Dalriadia. There was a time, soon after the legions left Britain, when the Picts ranged, like wolves clear to the southern coast. But the Jutes and Angles and Saxons drove them back into the heather country, and for so long has King Garth served as a buffer between them and Gerinth that he and his people have forgotten their ways.”

“Then you think Picts stole the princess? But how did they—?”

“That is for me to learn; that’s why we are heading for Ara. The Dalriadians and the Picts have been alternately fighting with each other and against each other for over a hundred years. Just now there is peace between them and the Scots are likely to know much of what goes on in the Dark Empire, as the Pictish kingdom is called—and dark it is, and strange. For these Picts come of an old, old race and their ways are beyond our ken.”

“And we will capture a Scot and question him?”

Cormac shook his head. “I will go ashore and mingle with them; they are of my race and language.”

“And when they recognize you,” grunted Wulfhere, “they will hang you to the highest tree. They have no cause to love you. True, you fought under King Gol in your early youth, but since then you have raided Dalriadia’s coasts more than once—not only with your Irish reivers, but with me, likewise.”

“And that is why I am growing a beard, old sea-dragon,” laughed the Gael.

Night had fallen over the rugged western coast of Caledon. Eastward loomed against the stars the distant mountains; westward, the dark seas stretched away to uncharted gulfs and unknown shores. The Raven rode at anchor on the northern side of a wild and rugged promontory that ran out into the sea, hugging close those beetling cliffs. Under cover of darkness Cormac had steered her inshore, threading the treacherous reefs of that grim shore with a knowledge born of long experience. Cormac Mac Art was Erin-born, but all the isles of the Western Sea had been his stamping ground since the day he had been able to lift his first sword.

“And now,” said Cormac, “I go ashore—alone.”

“Let me go with you!” cried Marcus, eagerly, but the Gael shook his head.

“Your appearance and accent would betray us both. Nor can you either, Donal, for though I know the kings of the Scots have listened to your harp, you are the only one besides myself who knows this coast, and if I fail to return you must take her out.”

The Gael’s appearance was vastly altered. A thick, short beard masked his features, concealing his scars. He had laid aside his horse-hair crested helmet and his finely worked mail shirt, and had donned the round helmet and crude scale mail corselet of the Dalriadians. The arms of many nations were part of the Raven’s cargo.

“Well, old sea-wolf,” said he with a wicked grin, as he prepared to lower himself over the rail, “you have said nothing, but I see a gleam in your eyes; do you also wish to accompany me? Surely the Dalriadians could have nothing but welcome for so kind a friend who has burnt their villages and sunk their hide-bottomed boats.”

Wulfhere cursed him heartedly. “We seafarers are so well loved by the Scots that my red beard alone would be enough to hang me. But even so, were I not captain of this ship, and bound by duty to it, I’d chance it rather than see you go into danger alone, and you such an empty-headed fool!”

Cormac laughed deeply. “Wait for me until dawn,” he instructed, “and no longer.”

Then, dropping from the after rail, he struck out for the shore, swimming strongly in spite of his mail and weapons. He swam along the base of the cliffs and presently found a shelving ledge from which a steep incline led upward. It might have taxed the agility of a mountain goat to have made the ascent there, but Cormac was not inclined to make the long circuit about the promontory. He climbed straight upward and, after a considerable strain of energy and skill, he gained the top of the cliffs and made his way along them to the point where they joined a steep ridge on the mainland. Down the southern slope of this he made his way toward the distant twinkle of fires that marked the Dalriadian town of Ara.

He had not taken half a dozen steps when a sound behind him brought him about, blade at the ready. A huge figure bulked dimly in the starlight.

“Hrut! What in the name of seven devils—”

“Wulfhere sent me after you,” rumbled the big carle. “He feared harm might come to you.”

Cormac was a man of irascible temper. He cursed Hrut and Wulfhere impartially. Hrut listened stolidly and Cormac knew the futility of arguing with him. The big Dane was a silent, moody creature whose mind had been slightly affected by a sword-cut on the head. But he was brave and loyal and his skill at woodcraft was second only to Cormac’s.

“Come along,” said Cormac, concluding his tirade, “but you cannot come into the village with me. You understand that you must hide outside the walls?”

The carle nodded, and motioning him to follow, Cormac took up his way at a steady trot. Hrut followed swiftly and silently as a ghost for all his bulk. Cormac went swiftly, for he would be crowded indeed to accomplish what he had set out to do and return to the dragon-ship by mid-day—but he went warily, for he expected momentarily to meet a party of warriors leaving or returning to the town. Yet luck was with him, and soon he crouched among the trees within arrow shot of the village.

“Hide here,” he whispered to Hrut, “and on no account come any nearer the town. If you hear a brawl, wait until an hour before dawn; then, if you have heard naught from me, go back to Wulfhere. Do you understand?”

The usual nod was the answer and as Hrut faded back among the trees, Cormac went boldly toward the village.

Ara was build close to the shore of a small, land-locked bay and Cormac saw the crude hide coracles of the Dalriadians drawn up on the beach. In these they swept south in fierce raids on the Britons’ and Saxons, or crossed to Ulster for supplies and reinforcements. Ara was more of an army camp than a town, the real seat of Dalriadia lying some distance inland.

The village was not a particularly imposing place. Its few hundred wattle and mud huts were surrounded by a low wall of rough stones, but Cormac knew the temper of its inhabitants. What the Caledonian Gaels lacked in wealth and armament they made up in unquenchable ferocity. A hundred years of ceaseless conflict with Pict, Roman, Briton and Saxon had left them little opportunity to cultivate the natural seeds of civilization that was an heritage of their native land. The Gaels of Caledonia had gone backward a step; they were behind their Irish cousins in culture and artisanship, but they had not lost an iota of the Gaelic fighting fury.

Their ancestors had come from Ulahd into Caledonia, driven by a stronger tribe of the southern Irish. Cormac, born in what was later known as Connacht, was a son of these conquerors, and felt himself not only distinct from these transplanted Gaels, but from their cousins in northern Erin. Still, he had spent enough time among these people to deceive them, he felt.

He strode up to the crude gate and shouted for entrance before he was perceived by the guard, who were prone to be lax in their vigilance in the face of apparent quietude—a universal Celtic trait. A harsh voice ordered him to stand still, while a torch thrust above the gate shone its flickering light full on him. In its illumination Cormac could see, framed above the gate, fierce faces with unkempt beards and cold grey or blue eyes.

“Who are you?” one of the guards demanded.

“Partha Mac Othna, of Ulahd. I have come to take service under your chief, Eochaidh Mac Aible.”

“Your garments are dripping wet.”

“And they were not it would be a marvel,” answered Cormac. “There was a boat load of us set sail from Ulahd this morning. On the way a Saxon sea-rover ran us down and all but I perished in the waves and the arrows the pirates rained upon us. I caught a piece of the broken mast and essayed to float.”

“And what of the Saxon?”

“I saw the sails disappear southward. Mayhap they raid the Britons.”

“How is it that the guard along the beach did not see you when you finally came ashore?”

“I made shore more than a mile to the south, and glimpsing the lights through the trees, came here. I have been here aforetime and knew it to be Ara, whither I was bound.”

“Let him in,” growled one of the Dalriadians. “His tale rings true.”

The clumsy gate swung open and Cormac entered the fortified camp of his hereditary foes. Fires blazed between the huts, and gathered close about the gate was the curious throng who had heard the guard challenge Cormac. Men, women and children partook of the wildness and savagery of their hard country. The women, splendidly built amazons with loose flowing hair, stared at him curiously, and dirty-faced, half-naked children peered at him from under shocks of tangled hair—and Cormac noted that each held’ a weapon of sorts. Brats scarcely able to toddle held a stone or a piece of wood. This symbolized the fierce life they led, when even the very babes had learned to snatch up a weapon at the first hint of alarm—aye, and to fight like wounded wildcats if need be. Cormac noted the fierceness of the people, their lean, hard savagery. No wonder Rome had never broken these people!

Some fifteen years had passed since Cormac had fought in the ranks of the ferocious warriors. He had no fear of being recognized by any of his former comrades. Nor, with his thick beard as a disguise, did he expect recognition as Wulfhere’s comrade.

Cormac followed the warrior who led him toward the largest hut in the village. This, the pirate was sure, housed the chieftain and his folk. There was no elegance in Caledonia. King Gol’s palace was a wattled hut. Cormac smiled to himself as he compared this village with the cities he had seen in his wanderings. Yet it was not walls and towers that made a city, he reflected, but the people within.

He was escorted into the great hut where a score of warriors were drinking from leather jacks about a crudely carved table. At the head sat the chief, known to Cormac of old, and at his elbow the inevitable minstrel—a characteristic of Celtic court life, however crude the court. Cormac involuntarily compared this skin-clad, shock-headed kern to the cultured and chivalrous Donal.

“Son of Ailbe,” said Cormac’s escort, “here is a weapon-man from Erin who wishes to take service under you.”

“Who is your chief?” hiccupped Eochaidh, and Cormac saw that the Dalriadian was drunk.

“I am a free wanderer,” answered the Wolf. “Aforetime I followed the bows of Donn Ruadh Mac Fin, flaith na Ulahd.”

“Sit ye down and drink,” ordered Eochaidh with an uncertain wave of his hairy hand. “Later I will talk with you.”

No more attention was paid to Cormac, except the Scots made a place for him and a shockheaded gilly filled his cup with the fiery potheen so relished by the Gaels. The Wolf’s ranging eye took in all the details of the scene, passed casually over the Dalriadian fighting-men and rested long on two men who sat almost opposite him. One of these Cormac knew—he was a renegade Norseman, Sigrel by name, who had found sanctuary among the foes of his race. Cormac’s pulse quickened as he caught the evil eyes of the man fixed narrowly on him, but the sight of the man beside the Norseman made him forget Sigrel for the moment.

This man was short and strongly made. He was dark, much darker than Cormac himself, and from a face as immobile as an idol’s, two black eyes glittered reptile-like. His square-cut black hair was caught back and confined by a narrow silver band about his temples, and he wore only a loin cloth and a broad leather girdle from which hung a short, barbed sword. A Pict! Cormac’s heart leaped. He had intended drawing Eochaidh into conversation at once and, by the means of a tale he had already fabricated, to draw from him any information he might have of the whereabouts of the princess Helen. But the Dalriadian chief was too drunk for that now. He roared barbaric songs, pounded the board with his sword hilt in accompaniment to the wild strains of his minstrel’s harp, and between times guzzled potheen at an astounding rate. All were drunk—all save Cormac and Sigrel, who furtively eyed the Gael over the rim of his goblet.

While Cormac racked his brain for a convincing way of drawing the Pict into conversation, the minstrel concluded one of his wild chants with a burst of sound and a rhyme that named Eochaidh Mac Ailbe “Wolf of Alba, greatest of raven-saters!”

The Pict reeled drunkenly to his feet, dashing his drinking-jack down on the board. The Picts habitually drank a smooth ale made from the heather blossoms. The fiery barley malt brewed by the Gaels maddened them. This particular Pict’s brain was on fire. His face, no longer immobile, writhed demoniacally and his eyes glowed like coals of black fire.

“True, Eochaidh Mac Ailbe is a great warrior,” he cried in his barbarous Gaelic, “but even he is not the greatest warrior in Caledonia. Who is greater than King Brogar, the Dark One, who rules the ancient throne of Pictdom? And next to him is Grulk! I am Grulk the Skull-cleaver! In my house in Grothga there is a mat woven of the scalps of Britons, Angles, Saxons—aye, and Scots!”

Cormac shrugged his shoulders in impatience. The drunken boastings of this savage would be likely to bring him a sword-thrust from the drink-fired Scots, that would cut off all chance of learning anything from him. But the Pict’s next words electrified the Gael.

“Who of all Caledonia has taken a more beautiful woman from the southern Britons than Grulk?” he shouted, reeling and glaring. “There were five of us in the hide-bottomed boat the gale blew southward. We went ashore in Gerinth’s realm for fresh water, and there we came upon three Britons deep in the forest—one lad and two beautiful maidens. The boy showed fight, but I, Grulk, leaping upon his shoulders, bore him to earth and disembowelled him with my sword. The women we took into our boat and fled with them northward, and gained the coast of Caledonia, and took the women to Grothga!”

“Words—and empty words,” sneered Cormac, leaning across the table. “There are no such women in Grothga now!”—taking a long chance.

The Pict howled like a wolf and fumbled drunkenly for his sword.

“When old Gonar, the high priest, looked on the face of the most finely dressed one—she who called herself Atalanta—he cried out that she was sacred to the moon god—that the symbol was upon her breast, though none but he could see. So he sent her, with the other, Marcia, to the Isle of Altars, in the Shetlands, in a long boat the Scots lent him, with fifteen warriors. The girl Atalanta is the daughter of a British nobleman and she will be acceptable in the eyes of Golka of the moon.”

“How long since they departed for the Shetlands?” asked Cormac, as the Pict showed signs of making a quarrel of it.

“Three weeks; the night of the Nuptials of the Moon is not yet. But you said I lied—”

“Drink and forget it,” growled a warrior, thrusting a brimming goblet at him. The Pict seized it with both hands and thrust his face into the liquor, guzzling ravenously, while the liquid slopped down on his bare chest.

Cormac rose from his bench. He had learned all he wished to know, and he believed the Scots were too drunk to notice his casual departure from the hut. Outside it might be a different matter to get past the wall. But no sooner had he risen than another was on his feet. Sigrel, the renegade Viking, came around the table toward him.

“What, Partha,” he said maliciously, “is your thirst so soon satisfied?”

Suddenly he thrust out a hand and pushed back the Gael’s helmet from his brows. Cormac angrily struck his hand away, and Sigrel leaped back with a yell of ferocious triumph.

“Eochaidh! Men of Caledonia! A thief and a liar is among you!”

The drunken warriors gaped stupidly.

“This is Cormac an Cliuin,” shouted Sigrel, reaching for his sword, “Cormac Mac Art, comrade of Wulfhere the Viking!

Cormac moved with the volcanic quickness of a wounded tiger. Steel flashed in the flickering torchlight and Sigrel’s head rolled grinning beneath the feet of the astonished revelers. A single bound carried the reiver to the door and he vanished while the Scots were struggling to their feet, roaring bewilderedly and tugging at their swords.

In an instant the whole village was in an uproar. Men had seen Cormac leap from the chief’s hut with his red-stained sword in his hand and they gave chase without asking the reason for his flight. The partially sobered feasters came tumbling out of the hut yelling and cursing, and when they shouted the real identity of their erstwhile guest a thunderous roar of rage went up and the whole village joined vengefully in the chase.

Cormac, weaving in and out among the huts like a flying shadow, came on an unguarded point of the wall and, without slackening his headlong gait, cleared the low barrier with a bound and raced toward the forest. A quick glance over his shoulder showed him that his escape had been seen. Warriors were swarming over the wall, weapons in their hands.

It was some distance to the first thick tangle of trees. Cormac took it full speed, running low and momentarily expecting an arrow between his shoulders. But the Dalriadians had no skill at archery and he reached the fringe of forest unscathed.

He had outfooted the fleet Caledonians, all save one who had outdistanced his fellows by a hundred yards and was now close upon the reiver’s heels. Cormac wheeled to dispose of this single foe, and even as he turned a stone rolled under his foot and flung him to his knee. He flung up his blade to block the sword that hovered over him like the shadow of Doom—but before it could fall, a giant shape catapulted from the trees, a heavy sword crashed down, and the Scot fell limply across Cormac, his skull shattered.

The Gael flung off the corpse and leaped to his feet. The yelling pursuers were close now, and Hrut, snarling like a wild beast, faced them—but Cormac seized his wrist and dragged him back among the trees. The next instant they were fleeing in the direction from which they had first come to Ara, ducking and dodging among the trees.

Behind them, and presently on either side, they heard the crashing of men through the underbrush, and savage yells. Hundreds of warriors had joined in the hunt of their arch-enemy. Cormac and Hrut slackened their speed and went warily, keeping in the deep shadows, flitting from tree to tree, now lying prone in the bushes to let a band of searchers go by. They had progressed some little distance when Cormac was galvanized by the deep baying of hounds far behind them.

“We are ahead of our pursuers now, I think,” muttered the Gael. “We might make a dash of it and gain the ridge and from thence the promontory and the ship. But they have loosed the wolfhounds on our trail and if we take that way, we will lead them and the warriors straight to Wulfhere’s ship. There are enough of them to swim out and board her and take her by storm. We must swim for it.”

Cormac turned westward, almost at right-angles to the course they had been following, and they quickened their pace recklessly—and emerging into a small glade ran full into three Dalriadians who assailed them with yells. Evidently they had not been ahead of their hunters as far as Cormac had thought, and the Gael, hurling himself fiercely into the fray, knew that the fight must be short or else the sound would bring scores of warriors hastening to the spot.

One of the Scots engaged Cormac while the other two fell upon the giant Hrut. A buckler turned Cormac’s first vicious thrust and the Dalriadian’s sword beat down on his helmet, biting through the metal and into the scalp beneath. But before the warrior could strike again, Cormac’s sword cut his left leg from under him, through the knee, and as he crumpled another stroke shore through his neck cords.

In the meantime Hrut had killed one of his opponents with a bear-like stroke that rended the upflung shield as though it had been paper and crushed the skull it sought to guard, and as Cormac turned to aid him, the remaining foe leaped in with the desperate recklessness of a dying wolf, and it seemed to the Gael that his stabbing sword sank half way to the hilt in the Dane’s mighty bosom. But Hrut gripped the Scot’s throat in his huge left hand, thrust him away and struck a blow that shore through corselet and ribs and left the broken blade wedged in the dead man’s spinal column.

“Are you hurt badly, Hrut?” Cormac was at his side, striving to undo the Dane’s rent corselet so that he might staunch the flow of blood. But the carle pushed him away.

“A scratch,” he said thickly. “I’ve broken my sword—let us haste.”

Cormac cast a doubtful look at his companion, then turned and hurried on in the direction they had been following. Seeing that Hrut followed with apparent ease, and hearing the baying of the hounds grow nearer, Cormac increased his gait until the two were running fleetly through the midnight forest. At length they heard the lapping of the sea, and even as Hrut’s breathing grew heavy and labored they emerged upon a steep rocky shore, where the trees overhung the water. To the north, jutting out into the sea could be seen the vague bulk of the promontory behind which lay the Raven. Three miles of rugged coast lay between the promontory and the bay of Ara. Cormac and Hrut were at a point a little over halfway between, and slightly nearer the promontory than the bay.

“We swim from here,” growled Cormac, “and it’s a long swim to Wulfhere’s ship, around the end of the promontory for the cliffs are too steep to climb on this side—but we can make it and the hounds can’t follow our tracks in the water—what in the name of gods—!”

Hrut had reeled and pitched headlong down the steep bank, his hands trailing in the water. Cormac reached him instantly and turned him on his back; but the Dane’s fierce face was set in death. Cormac tore open his corselet and felt beneath it for an instant, then withdrew his hand and swore in amazement at the vitality that had enabled the carle to run for nearly half a mile with that terrible wound beneath his heart. The Gael hesitated; then to his ears came the deep baying of the hounds. With a bitter curse he tore off his helmet and corselet and threw them aside, kicking off his sandals. Drawing his sword belt up another notch, he waded out into the water and then struck out strongly.

In the darkness before dawn Wulfhere, pacing the deck of his dragon-ship, heard a faint sound that was not the lapping of the waves against the hull or the cliffs. With a quick word to his comrades, the Dane stepped to the rail and peered over. Marcus and Donal pressed close behind him, and presently saw a ghostly figure clamber out of the water and up the side. Cormac Mac Art, blood-stained and half naked, clambered over the rail and snarled:

“Out oars, wolves, and pull for the open sea, before we have half a thousand Dalriadians on our backs! And head her prow for the Shetlands—the Picts have taken Gerinth’s sister there.”

“Where’s Hrut?” rumbled Wulfhere, as Cormac started toward the sweep-head.

“Drive a brass nail into the main-mast,” snarled the Gael. “Gerinth owes us ten pounds already.” The bitterness in his eyes belied the harsh callousness of his words.

Marcus paced the deck of the dragon-ship. The wind filled the sails and the long ash oars of the rowers sent the long, lean craft hurtling through the water, but to the impatient Briton it seemed that they moved at a snail’s pace.

“But why did the Pict call her Atalanta?” he cried, turning to Cormac. “True, her maid was named Marcia—but we have no real proof that the woman with her is the princess Helen.”

“We have all the proof in the world,” answered the Gael. “Do you think the princess would admit her true identity to her abductors? If they knew they held Gerinth’s sister, they would have half his kingdom as ransom.”

“But what did the Pict mean by the Nuptials of the Moon?”

Wulfhere looked at Cormac and Cormac started to speak, shot a quick glance at Marcus and hesitated.

“Tell him,” nodded Donal. “He must know eventually.”

“The Picts worship strange and abhorrent gods,” said the Gael, “as is well known to we who roam the sea, eh Wulfhere?”

“Right,” growled the giant. “Many a Viking has died on their altar stones.”

“One of their gods is Golka of the Moon. Every so often they present a captured virgin of high rank to him. On a strange, lonely isle in the Shetlands stands a grim black altar, surrounded by columns of stone, such as you have seen at Stonehenge. On that altar, when the moon is full, the girl is sacrificed to Golka.”

Marcus shuddered; his nails bit into his palms.

“Gods of Rome, can such things be?”

“Rome has fallen,” grunted the Skull-splitter. “Her gods are dead. They will not aid us. But fear not—” he lifted his gleaming, keen-edged axe, “here is that which will aid us. Let me lead my wolves into the stone circle and we will give Golka such a blood-sacrifice as he has never dreamed of!”

“Sail on the port bow!” came the sudden shout of the look-out in the cross-trees. Wulfhere wheeled suddenly, beard bristling. A few moments later all on board could make out the long, low lines of the strange craft.

“A dragon-ship,” swore Cormac, “and making full speed with oar and sail—she means to cut across our bows, Wulfhere.”

The chieftain swore, his cold blue eyes beginning to blaze. His whole body quivered with eagerness and a new roaring note came into the voice that bellowed commands to his crew.

“By the bones of Thor, he must be a fool! But we’ll give him his fill!”

Marcus caught the Dane’s mighty arm and swung him about.

“Our mission is not to fight every sea-thief we meet,” the young Briton cried angrily. “You were engaged to search for the princess Helen; we must not jeopardize this expedition. Now we have at last a clue; will you throw away our chances merely to glut your foolish lust for battle?”

Wulfhere’s eyes flamed.

“This to me on my own deck?” he roared. “I’ll not show my stern to any rover for Gerinth and all his gold! If it’s fight he wants, it’s fight he’ll get.”

“The lad’s right, Wulfhere,” said Cormac quietly, “but by the blood of the gods we’ll have to run for it, for yon ship is aimed straight for us and I see a running about on the deck that can mean naught but preparation for a sea-fight.”

“And run we cannot,” said Wulfhere in deep satisfaction, “for I know her—that ship is Rudd Thorwald’s Fire-Woman, and he is my life-long enemy. She is as fleet as the Raven and if we flee we will have her hanging on our stern all the way to the Shetlands. We must fight.”

“Then let us make it short and desperate,” snapped Cormac, scowling. “There’s scant use in trying to ram her; run alongside and we’ll take her by storm.”

“I was born in a sea-fight, and I sank dragon-ships before I ever saw you,” roared Wulfhere. “Take the sweep-head.” He turned to Marcus. “Hast ever been in a sea-brawl, youngster?”

“No, but if I fail to go further than you can lead, hang me to your dragon-beak!” snapped the angered Briton. Wulfhere’s cold eyes glinted in amused appreciation as he turned away.

There was little maneuvering of ships in that primitive age. The Vikings attained the sea-craft they had in a later day. The long, low serpents of the sea drove straight for each other, while warriors lined the sides of each, yelling and clashing sword on shield.

Marcus, leaning on the rail, glanced at the wolfish warriors beside and below him, and glanced across the intervening waves at the fierce, light-eyed, yellow-bearded Vikings who lined the sides of the opposing galley—Jutes they were, and hereditary enemies of the red-maned Danes. The young Briton shuddered involuntarily, not from fear but because of the innate, ruthless savagery of the scene, as a man might shudder at a pack of ravening wolves, without fearing them.

And now there came a giant twanging of bowstrings and a rain of death leaped through the air. Here the Danes had the advantage; they were the bowmen of the North Sea. The Jutes, like their Saxon cousins, knew little of archery. Arrows came whistling back, but their flight lacked the deadly accuracy of the Danish shafts. Marcus saw men go down in windrows aboard the Juttish craft, while the rest crouched behind the shields that lined the sides. The three men at the sweep-head fell and the long sweep swung in a wide, erratic arc; the galley lost way and Marcus saw a blond giant he instinctively knew to be Rudd Thorwald himself leap to the sweep-head. Arrows rattled off his mail like hailstones, and then the two craft ran alongside with a rending and crashing of oars and a grinding of timbers.

The wolf-yell of the Vikings split the skies and in an instant all was a red chaos. The grappling hooks bit in, gripping keel to keel. Shields locked, the double line writhed and rocked as each crew sought to beat the other back from its bulwarks and gain the opposing deck. Marcus, thrusting and parrying with a wild-eyed giant across the rails, saw in a quick glance over his foe’s shoulder Rudd Thorwald rushing from the sweep-head to the rail. Then his straight sword was through the Jute’s throat and he flung one leg over the rail. But before he could leap into the other ship, another howling devil was hacking and hewing at him, and only a shield suddenly flung above his head saved his life. It was Donal the minstrel who had come to his aid.

Toward the waist of the ship, Wulfhere surged on through the fray and one mighty sweep of his axe cleared a space for him for an instant. In that instant he was over the rail on the deck of the Fire-Woman and Cormac, Thorfinn, Edric and Snorri were close behind him. Snorri died the moment his feet touched the Fire-Woman’s deck and a second later a Juttish axe split Edric’s skull, but already the Danes were pouring through the breach made in the lines of the defenders and in a moment the Jutes were fighting with their backs to the wall.

On the blood-slippery deck the two Viking chieftains met. Wulfhere’s axe hewed the shaft of Rudd Thorwald’s spear in twain, but before the Dane could strike again, the Jute snatched a sword from a dying hand and the edge bit through Wulfhere’s corselet over his ribs. In an instant the Skull-splitter’s mail was dyed red, but with a mad roar he swung his axe in a two-handed stroke that rent Rudd Thorwald’s armor like paper and cleft through shoulder bone and spine. The Juttish chief fell dead in a red welter of blood and the Juttish warriors, disheartened, fell back, fighting desperately.

The Danes yelled with fierce delight. But the battle was not over. The Jutes, knowing there was no mercy for the losers of a sea-fight, battled stubbornly. Marcus was in the thick of it, with Donal close at his side. A strange madness had gripped the young Briton. To his mind, distorted momentarily by the fury of the fray, it seemed that these Jutes were holding him back from Helen. They stood in his way and while he and his comrades wasted time with them, Helen might be in desperate need of rescue. A red haze burned before Marcus’ eyes and his sword wove a web of death in front of him. A huge Jute dented his shield with a sweeping axe-head and Marcus flung his shield away, ripping the warrior open with the other hand.

“By the blood of the gods,” Cormac rasped, “I never heard before that Romans went berserk, but—”

Marcus had forced his way over the corpse-littered benches to the poop. A sword battered down on his helm as he leaped upward, but he paid no heed; even as he thrust mechanically, his eyes fell on a strangely incongruous ornament suspended by a slender, golden chain from the Jute’s bull neck. On the end of that chain, glittering against his broad, mailed chest, hung a tiny jewel—a single ruby carved in the symbol of the acanthus. Marcus cried out like a man with a death wound under his heart and like a madman plunged in blindly, scarcely knowing what he did. He felt his blade sink deep and the force of his charge hurled him to the poop deck on top of his victim.

Struggling to his knees, oblivious to the hell of battle about him, Marcus tore the jewel from the pirate’s neck and pressed it to his lips. Then he gripped the Jute’s shoulders fiercely.

“Quick!” he cried in the tongue of the Angles, which the Jutes understood. “Tell me, before I rend the heart from your breast, whence you got this gem!”

The Jute’s eyes were already glazing. He was past acting on his own initiative. He heard an insistent voice questioning him, and answered dully, scarcely knowing that he did so: “From one of the girls we took . . . from the . . . Pictish boat.”

Marcus shook him, frantic with a sudden agony. “What of them? Where are they?”

Cormac, seeing something was forward, had broken from the fight and now bent, with Donal, over the dying pirate.

“We . . . sold . . . them,” muttered the Jute in a fading-whisper, “to . . . Thorleif Hordi’s son . . . at. . . .”

His head fell back; the voice ceased.

Marcus looked up at Donal with pain-haunted eyes.

“Look, Donal,” he cried, holding up the chain with the ruby pendant. “See? It is Helen’s! I myself gave it to her—she and Marcia were on this very ship—but now—who is this Thorleif Hordi’s son?”

“Easy to say,” broke in Cormac. “He is a Norse reiver who has established himself in the Hebrides. Be of good cheer, young sir; Helen is better off in the hands of the Vikings than in those of the Pictish savages of the Hjaltlands.”

“But surely we must waste no time now!” cried Marcus. “The gods have cast this knowledge into our hands; if we tarry we may again be put upon a false scent!”

Wulfhere and his Danes had cleared the poop and waist, but on the after deck the survivors still stubbornly contended with their conquerors. There was scant mercy shown in a sea-fight of that age. Had the Jutes been victorious they would have spared none; nor did they expect or ask for mercy.

Cormac made his way through the waist of the ship where dead and dying lay heaped, and struggled his way through the yelling Danes to where Wulfhere stood plying his dripping axe. By main force he tore the Skull-splitter from his prey and jerked him about.

“Have done, old wolf,” he growled. “The fight is won; Rudd Thorwald is dead. Would you waste steel on these miserable carles?”

“I leave this ship when no Jute remains alive!” thundered the battle-maddened Dane. Cormac laughed grimly.

“Have done! Bigger game is afoot! These Jutes will drink blood before you slaughter them all and we will need every man before the faring is over. From the lips of a dying Jute we have heard it—the princess is in the steading of Thorleif Hordi’s son, in the Hebrides.”

Wulfhere’s beard bristled with ferocious joy. So many were his foes that it was hard to name a Viking farer with whom he had no feud.

“Is it so? Then, ho, wolves—leave the rest of these sea-rats to drown or swim as they will! We go to burn Thorleif Hordi’s son’s skalli over his head!”

Slowly, by words and blows, he beat his raging Danes off and, marshalling them together, drove them over the gunwales into their own ship. The bleeding, battle-weary Jutes watched them go, leaning on their reddened weapons in sullen silence. The toll taken had been terrific, but by far the greater loss aboard the Fire-Woman. From stem to stern dead men wallowed among the broken benches in a welter of crimson.

“Ho, rats!” Wulfhere shouted, as his Vikings cast off and the oars of the Raven began to ply, “I leave you your blood-gutted craft and the carrion that was Rudd Thorwald. Make the best you can of them and thank the gods that I spared your lives!”

The losers harkened in sullen silence, answering only with black scowls, all save one—a lean, wolfish figure of a warrior, who brandished a notched and bloody axe and shouted: “Mayhap you will curse the gods some day, Skull-splitter, because you spared Halfgar Wolf’s-tooth!”

It was a name, in sooth, that Wulfhere had cause to remember well in later days. But now the chief merely roared in laughter, though Cormac Mac Art frowned.

“It is a foolish thing to taunt beaten men, Wulfhere,” said he. “But you have a nasty cut across your ribs. Let me see to it.”

Marcus turned away with the gem that Helen had worn. The flood of savagery during the last few hours left him dazed and weary. But he had discovered strange, dark deeps in his own soul. A few minutes of fierce sword-play on the gunwales of a sea-rover had sufficed to bridge the gap of three centuries. Coolness in action, a characteristic drilled into his forebears by countless Roman officers, and inherited by him, had been swept away in an instant before the wild, old Celtic fury before which Caesar had staggered on the Ceanntish beaches. For a few mad moments he had been one with the wild men about him. The shadows of Rome were fading; was he, too, like all the world, reverting to the nature of his British ancestors, bloodbrothers in savagery to Wulfhere Skull-splitter?

“It is not far from here to Kaldjorn where Thorleif Hordi’s son has built his steading,” said Cormac, glancing abstractedly at the mast where now sixteen brass nails gleamed dully.

The Norse were already establishing themselves in the Hebrides, the Orkneys and the Shetlands. Later these movements would become permanent colonizations; at this time, however, their steadings were merely pirate camps.

“The Sudeyar lie to the east, just out of sight over the sea-rim,” Cormac continued. “We must resort to craft again. Thorleif Hordi’s son has four long ships and three hundred carles. We have one ship and less than eighty men. We can not do as Wulfhere wishes: go ashore and burn Thorleif’s skalli—and he will not be likely to give up such a prize as the princess Helen without a battle.

“This is what I suggest: Thorleif’s steading is on the east side of the isle of Kaldjorn, which luckily is a small one. We will draw in under cover of night, on the west side. There are high cliffs there and the ship should be safe from detection for a time, since none of Thorleif’s folk have any reason to wander about on the western part of the island. Then I will go ashore and seek to steal the princess.”

Wulfhere laughed. “You will find it a more difficult matter to hoax the Norse than you did the Scots. Your locks will brand you as a Gael and they will cut the blood-eagle in your back.”

“I will creep among them like a serpent and they will know naught of my coming,” answered the Gael. “Your Norseman is a very dullard when it comes to stealth, and easy to deceive.”

“I will go with you,” broke in Marcus. “This time I will not be denied.”

“While I must gnaw my thumb on the west side of the isle,” grumbled Wulfhere enviously.

“Wait,” said Donal. “I have a better plan, Cormac.”

“Say on,” the Gael prompted him.

“We shall buy the princess from Thorleif Hordi’s son. Wulfhere—how much loot have you aboard this ship?”

“Enough gold to ransom a noble lady, mayhap,” grunted the Dane, “but not enough to buy back Gerinth’s sister—that would cost half a kingdom. Moreover, Thorleif is my blood-enemy, and would rather see my head on a spear at his skalli-door than all Gerinth’s gold in his coffers.”

“Thorleif need not know this is your ship,” said Donal. “Nor can he know that the lady he holds captive is the princess Helen; to him she will be the lady Atalanta, no more. Now, here is my plan: you, Wulfhere, shall disguise yourself and take your place with your warriors, while Thorfinn, your second-in-command, acts as chief. Marcus here shall play the part of Atalanta’s brother, while I shall be her childhood mentor; we shall say we have come to ransom her, cost what it may—hiring this Viking-crew to aid us, since the Britons have no more ships and no men to spare from their borders.”

“It will cost a-plenty,” grumbled Wulfhere. “Thorleif is as shrewd as he is rapacious; he will drive a hard bargain.”

“Let him. Gerinth will pay you back, though it cost you all the loot in your hold. The king has sent me with you to be his judge in these matters—and let my head be forfeit for any promise I should make in his name, for he shall keep it!”

“I trust your sincerity and Gerinth’s,” said Wulfhere, “yet this plan is not to my liking. Rather would I fall on Thorleif’s skalli like a thunderbolt, with arrow-storm and sharp-edged steel.”

“As would I,” said Cormac; “yet Donal’s plan is best if rescue of the princess Helen is our goal. Thorleif’s carles outnumber us at least three to one, and even were we to best them in a surprise attack the princess might well be slain in the fray. Donal’s plan is good; Thorleif would contest us with steel were he to know whom he holds as captive, but if he thinks he holds hostage only a noble lady of the Britons, Atalanta, then doubtless he’ll accept a hold full of loot for her rather than risk his ships and men in a fight. And if Donal’s plan fails, then we’ll still have mine to try.”

“Well,” said Wulfhere, “there’s wisdom in Donal’s way, I’ll not gainsay it. But I’ll stay on the strand with the crew while Thorfinn and Marcus and Donal bargain for Gerinth’s sister, lest I should betray our venture; for I have sworn that when next I see Thorleif Hordi’s son’s treacherous face I shall cleave it to the chin!”

“I’ll be in on the bargaining,” said Cormac. “Thorleif shall not recognize me through this beard.”

“Likely not,” grunted the Dane, “for he saw you but briefly, and that during a sea-fight. Yet I’ll be ready to lead the crew in a charge should aught go wrong at the dickering. Steersman!” he bellowed, “make for the Scottish mainland—we’ll need a day’s rest to lick our wounds and gather provisions before we sail for the Hebrides.”

As the ship headed for the wild coastland, not one man of its sharp-eyed crew noticed the ship of the defeated Jutes, with barely enough men left to man the oars, bearing off across the horizon of the gray sea toward the northeast, its square sail belled to the wind, its rowers working frantically—

Nor, far in its wake, too far to be seen save by the most keen-eyed of lookouts, the small, dark longboat full of small, dark men—men with bows, flint-tipped arrows and dark eyes full of intent watchfulness and grim purpose.

A cold, thin drizzle chilled the air and made the rocks on the beach before Thorleif Hordi’s son’s steading glimmer as if with dark slime. Beyond drifting wraiths of mist the forest of spruce and pine rose like minarets in a sea of murk. Four long ships lay drawn up on the shore. Farther down the beach lay a fifth with the forepart of its keel upon the sand; near it stood a large band of red-bearded men in scale mail corselets and horned helmets, bearing spears, bows and shields. A high wall of pointed logs paralleled the upper edge of the beach, and from behind this wall rose smoke from the skalli of Thorleif and the lesser dwellings of his carles; while before it and about its broad gate stood ranked over a hundred blond Vikings, armored and armed much like those clustered about the lone long ship. Between the two large bands of warriors, some distance from either, stood a small knot of men divided into two parts and facing one another.

“Bring forth your loot,” rumbled Thorleif Hordi’s son. “You’ll not purchase the Lady Atalanta without a lot of it. By Odin, she’s a comely wench, and I’d minded to have her for one of my own brides.”

Cormac eyed the huge Viking chieftain closely. Thorleif was a giant of a man, greater even than Wulfhere, with a face pitted with scars and creased with lines of hard cruelty. There was a gap in the jawline where pale flesh showed through the thick blond beard, and Cormac hoped the man would not remember who had given him that scar in battle; but the Gael’s dark beard had grown thickly, and Thorleif had given no sign of recognition since the opening of negotiations.

“What is a wench to you,” said Cormac, “even a noble one, to a hold full of riches? Bring the lady forth, and we’ll lay the gold at your feet.”

“The gold first,” grunted Thorleif. “If it’s not enough, I’ll keep her.”

“Who will pay you more,” said Donal, “than her own brother? Your raids will bring you wenches aplenty, even noble ones; but the price offered you by the noble Marcus, Atalanta’s brother, is far greater than another would pay, as you must well know.”

“Aye,” said Marcus, “and if you’ll not accept this lavish sum, I’ll spend a greater to return with a fleet that’ll sweep this island clean of pirates! By Christ, when Rome was in power. . . .”

Thorleif laughed; Cormac laid a hand on Marcus’ shoulder.

“Rome is dead!” roared the Viking. “And not even at the height of her power did her rule touch these islands. But you are a headstrong youth. If you could bring an army here, why do you come now with this single shipload of Danish pirates? Bah! bring forth your gold, and I’ll decide whether it’s worthy to ransom the Lady Atalanta and her maid.”

Cormac signalled the group of Danes clustered about the long ship, and a dozen of them lifted burdens and trudged up the beach toward the debating parties.

“ ’Ware a trap,” growled one of Thorleif’s aides—a lean, hard sea-wolf. “We be but twenty here, and with this approaching twelve they will outnumber us.”

“Well, then—” Thorleif raised his hand, and twenty men detached themselves from those ranks by the fortress-wall, striding down the beach to join the score or so that already formed his band. Cormac felt a twinge of suspicion. Then Thorleif turned to the Viking Thorfinn and said: “I recognize your ship, the Raven—it belonged to my enemy Wulfhere Hausakluifr. How came you into possession of it?”

“Wulfhere was my captain,” said Thorfinn, “but he wronged me and I split his skull in combat.”

The dozen men from the Danish ship joined the group and let fall their burdens on the beach. Knives ripped open the cloth bags and a glittering profusion of gold-wrought works of art and sparkling jewelry spilled out on the sand.

“This is a ransom worthy of a princess,” said Donal, “not merely a noble lady. Give us Atalanta and we shall go in peace.”

The eyes of Thorleif Hordi’s son lit up at the sight of so much gold and jewelry. “Let it be so,” he said, and Cormac relaxed slightly. The twenty-odd men who had detached themselves from the ranked warriors near the wall had now joined Thorleif’s group; the Gael now saw that in their midst was a woman of surpassing beauty, and he knew that she could be none other than the princess Helen. Yet as she drew closer he saw that her white garments were torn—her dark hair was in disarray—her beautiful features were strained as if in agony, and her wide dark eyes seemed to burn with a hopeless yearning, a mute appeal mingled with a near-hopeless resignation.

“Helen!”

The girl looked up at the sound of Marcus’ involuntary cry; her face suddenly lost its look of hopeless apathy and took on an expression of animation and joy. Then, before her guards could stop her, she leaped away and dashed across the narrow space between the two opposing groups and threw herself into her lover’s arms.

“Marcus—oh Marcus, help me!” she cried. “They tortured Marcia—O God! They made her tell all, and then they killed her—and they mean to kill you. Flee, Marcus—flee! It’s a trap!”

Suddenly Cormac saw, too late, that the men who had joined Thorleif’s delegation were not Vikings but—Jutes. In the fore-front of them stood Halfgar Wolf’s-tooth—and Cormac suddenly realized that the twenty-odd men who had joined Thorleif’s party were the survivors of the Juttish ship Fire-Woman.

“Fools!” roared Thorleif. “I knew who you were from the start of your thievish bargainings. These Juttish wolves sailed night and day to beat you here, for a wounded member of their crew overheard what Marcus learned from the dying carle. Aye, the princess Helen, sister of Gerinth, is she you seek to regain—deny it not, for Halfgar and I learned it from the lips of the maid Marcia ere she died under the torture. And now you shall die also, Cormac Mac Art, and your fool chieftain who doubtless hides amid his red-bearded carles by the long ship. I shall have your treasure, your long ship, the princess Helen—and the head of Wulfhere!”

Marcus, only half-comprehending what was said, looked up from Helen’s tear-stained face and realized that Thorleif and Halfgar were the ones who had tortured the girl beyond endurance. With a frantic roar he unsheathed his sword and drove straight at Thorleif. The Viking chief laughed as he drew his own blade and parried the youth’s frantic stroke.

“Devil!” shrieked Marcus. “I’ll have your heart. . . .”

Thorleif laughed again as his blade parried Marcus’ once more and shattered the youth’s sword like glass. Marcus sprang for the Viking with a fury equal to the Norseman’s berserker-rage, and only Cormac’s sword, intercepting Thorleif’s whistling blade, saved the youth from a split skull; as it was, the Gael’s blade was shattered to flinders as well. Then Marcus leaped and his fingers locked about Thorleif’s throat; the bearlike Viking gasped at the steely grip of the youth’s fingers, at the desperate strength and ferocity of the Briton who was scarcely half his weight, and tried to cry out in terror, but felt his windpipe choked off. Dropping his sword, useless at these close quarters, he battered with his massive fists at the youth’s rib-cage till Marcus fell back, half conscious yet still clutching at the Viking’s bull neck. . . .

The Norsemen rushed in and Cormac, striving to save Marcus from the bull-like Thorleif, was driven back. A fierce blond warrior swung at him with an axe; Cormac’s shield fended off the blow but his broken sword left him helpless to retaliate; then, as the Viking hove up his axe for another stroke, Donal’s blade darted in to pierce the links of his scale armor and the warrior crashed to the earth like a fallen tree. Cormac saw a Juttish warrior leaping toward Donal like a maddened wolf; with all his strength he sprang and interposed his battered shield between Donal and the Jute’s axe. The arching blade crashed through the lifted shield and Cormac cried out involuntarily as pain lanced his left arm; then Donal’s sword slashed in a silvery arc and the Juttish carle fell with his head half-severed, blood spurting from his heart-veins while his last dying war-cry turned abruptly to bloody gurglings from his sundered windpipe.

Battle-cries rang out and the clash of steel filled the air. Cormac rose shakily as the battle surged about him; his right hand clutched the hilt of a broken sword, his shield hung shattered on his bleeding left arm. He saw, amid the press of fighting-men around him, Thorleif Hordi’s son contending against Wulfhere’s captain Thorfinn, who held his ground with valor while Marcus attempted to crawl away with the fainting Helen. Then, even as Cormac watched, a dying Jute slashed across Thorfinn’s ankles with a dagger and the Dane fell—and as he fell Thorleif’s blade lashed out and split his skull. Donal was engaged with the lean Viking who was Thorleif’s lieutenant, and Cormac saw with horror that Thorleif Hordi’s son was about to cleave the defenseless Marcus in half as he strove to hurry Helen to safety. Without thinking Cormac roared and launched himself toward the Viking; Thorleif wheeled and, seeing the Gael charging him with shattered blade and broken shield, laughed aloud and hove his sword aloft for the death-stroke. . . .

Cormac wheeled and dodged the whistling blade just in time. Then his foot slipped in a patch of beach-slime and he fell sprawling. Thorleif hove up his sword for a final blow—but as he swung it down the blade crashed on an upraised shield and suddenly he was gazing into the blazing eyes of Wulfhere the Skull-splitter.

“Smite again!” roared the Danish chieftain. “Aye, try your steel against another than wounded warriors and helpless women, spawn of Helheim!”

Cormac lurched to his feet and raced to the aid of Marcus; a Norse warrior surged to stop him, but Cormac was beneath the sweep of the man’s axe like a cat and his broken sword ripped into his bull-throat.

Thorleif Hordi’s son roared with rage and struck with all his might, and his great thick-bladed sword crashed ringingly against the rim of Wulfhere’s horned helmet and sent sparks flying. The Danish chief reeled back, half-dazed, and Thorleif rushed in for the kill; but Wulfhere, rallying, roared and swung his axe with all his strength. The axe-blade dipped beneath Thorleif’s shield and crunched in through steel mail and into flesh. Thorleif, maddened, lashed back with a blow that clove Wulfhere’s shield asunder—but the Dane, bellowing like a wounded bear, gave back a blow of his axe that shore through the Norseman’s helmet and split his skull to the jawbone, and Thorleif crashed to the earth like a felled tree.

The battle raged like a maelstrom of steel as the Danes from the long ship rushed to battle with the Norse warriors, who in turn had charged from their position by the stockade-wall. Cormac raced to the side of Marcus, who with the help of Donal was protecting the princess Helen.

“Back to the ship!” yelled Cormac. “Leave the treasure and forget your blood-feuds! Protect the princess!”

The Danes paused in their retreat to draw bow to ear, and at least a score of the charging Norsemen went down before a storm of arrows, somewhat evening the odds—but the rest came on. Halfgar and his Jutes had retreated slightly, but now with their Norse allies at their backs returned to the offense with wild war-cries. The rushing factions crashed together in a storm of ringing steel; flashing blades ripped through mail and flesh, bones snapped under the impact of mighty blows, and in a moment the beach-stones were slippery with blood while Dane strove against Jute and Norseman in a desperate fury that neither gave nor asked for quarter. Halfgar slew a Dane with a mighty stroke of his axe, then leaped for Donal who was warding the frightened princess. Donal was a competent swordsman but he could not stand before the berserker fury of the Jute’s charge; the force of Halfgar’s blow against the buckler he threw up barely in time drove him to his knees. Then the Juttish chief hove up his axe for a killing blow.

Cormac, his sword and shield useless, tensed to charge Halfgar bare-handed—yet knew with a pang of despair that he was too far away to avert the blow that would slay Donal. Then with a roar of rage a hurtling form crashed into the Jute and the two went down together, threshing and snarling. It was Marcus, unarmed, yet in the grip of a berserker-rage as terrible as any Viking’s.

Cormac ducked a singing sword-blade, leaped under his attacker’s guard and drove his dagger against the warrior’s scale-mail with all his strength. The blade snapped—but not before it had ripped through the mail and buried itself deep in the Viking’s heart.

Snatching up the fallen warrior’s sword and shield, Cormac leaped to where Marcus and Halfgar were battling. The young Briton was having the worst of it; his wounds had weakened him, and his strength was not equal to his fury. Even as Cormac sprang forward Halfgar broke the furious grip of his opponent and smashed the front of his shield into the youth’s face; then, even as he shifted his axe to slay the stunned Marcus, the Jute saw a glitter of bright crimson at his feet. It was the gem that had adorned the princess Helen, its slender chain now broken, torn from Marcus during the fight. Halfgar stooped quickly and snatched it up, hastily looping the chain round his axe-belt. That instant of avarice was all Cormac needed to close the gap and save Marcus from the stroke of a butcher’s axe; when the Jute looked up the Gael was already upon him like a whirlwind of fury. He hove up his axe in an instinctive attempt to ward off Cormac’s furious stroke, but the sword-blade bit through the handle, sending the axe-head flying, and crashed to fragments on his iron helm. The good metal saved Halfgar’s skull but the force of Cormac’s blow sent the Jute crashing senseless to the beach.

“Fall back to the ship,” yelled Cormac. “Aid here for the prince Marcus!”

Donal rushed to Cormac’s aid, and the princess Helen with him, her face white and tearful but strong with a concern that overrode her fear. Ignoring Cormac’s bewildered cursings, she helped the minstrel lift the stunned Marcus and bear him away.

The Jutes and Norsemen, having seen both their chieftains fall, had momentarily slackened in their battle-fury; but now, seeing the Danes withdrawing rapidly toward their ship with the hostage British noblewoman in their midst, they surged back to the fight with renewed frenzy. And then, as if in answer to a prearranged signal, the war-cries of a mighty host came roaring from the far end of the beach, beyond which the Raven lay with her prow on the sand—and from the forest burst a horde of charging Norsemen that outnumbered both the contesting groups put together.

“The trap’s sprung!” yelled Cormac, raging. “To the ship!”

“Wotan!” Wulfhere scattered a Norseman’s brains with a mighty stroke of his axe. “Let your blades drink blood, sons of Dane-mark!”