Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

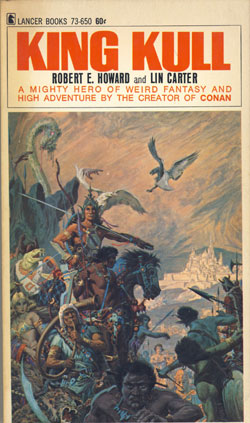

Published in King Kull, 1967.

| I. “My Songs Are Nails for a King’s Coffin!” II. “Then I Was The Liberator—Now—” |

III. “I Thought You a Human Tiger!” IV. “Who Dies First?“ |

“At midnight the king must die!”

The speaker was tall, lean and dark, and a crooked scar close to his mouth lent him an unusually sinister cast of countenance. His hearers nodded, their eyes glinting. There were four of these—one was a short fat man, with a timid face, weak mouth and eyes which bulged in an air of perpetual curiosity—another a great somber giant, hairy and primitive—the third a tall, wiry man in the garb of a jester whose flaming blue eyes flared with a light not wholly sane—and last a stocky dwarf of a man, inhumanly short and abnormally broad of shoulders and long of arms.

The first speaker smiled in a wintry sort of manner. “Let us take the vow, the oath that may not be broken—the Oath of the Dagger and the Flame. I trust you—oh, yes, of course. Still, it is better that there be assurance for all of us. I note tremors among some of you.”

“That is all very well for you to say, Ascalante,” broke in the short fat man. “You are an ostracized outlaw, anyway, with a price on your head—you have all to gain and nothing to lose, whereas we—”

“Have much to lose and more to gain,” answered the outlaw imperturbably. “You called me down out of my mountain fastnesses to aid you in overthrowing a king—I have made the plans, set the snare, baited the trap and stand ready to destroy the prey—but I must be sure of your support. Will you swear?”

“Enough of this foolishness!” cried the man with the blazing eyes. “Aye, we will swear this dawn and tonight we will dance down a king! ‘Oh, the chant of the chariots and the whir of the wings of the vultures—’ ”

“Save your songs for another time, Ridondo,” laughed Ascalante. “This is a time for daggers, not rhymes.”

“My songs are nails for a king’s coffin!” cried the minstrel, whipping out a long lean dagger. “Varlets, bring hither a candle! I shall be first to swear the oath!”

A silent and sombre slave brought a long taper and Ridondo pricked his wrist, bringing blood. One by one the other four followed his example, holding their wounded wrists carefully so that the blood should not drip yet. Then gripping hands in a sort of circle, with the lighted candle in the center, they turned their wrists so that the blood drops fell upon it. While it hissed and sizzled, they repeated:

“I, Ascalante, a landless man, swear the deed spoken and the silence covenanted, by the oath unbreakable!”

“And I, Ridondo, first minstrel of Valusia’s courts!” cried the minstrel.

“And I, Volmana, count of Karaban,” spoke the dwarf.

“And I, Gromel, commander of the Black Legion,” rumbled the giant.

“And I, Kaanuub, baron of Blaal,” quavered the short fat man, in a rather tremulous falsetto.

The candle sputtered and went out, quenched by the ruby drops which fell upon it.

“So fade the life of our enemy,” said Ascalante, releasing his comrades’ hands. He looked on them with carefully veiled contempt. The outlaw knew that oaths may be broken, even “unbreakable” ones, but he knew also that Kaanuub, of whom he was most distrustful, was superstitious. There was no use overlooking any safe guard, no matter how slight.

“Tomorrow,” said Ascalante abruptly, “I mean today, for it is dawn now, Brule the Spear-slayer, the king’s right hand man, departs from Grondar along with Ka-nu the Pictish ambassador, the Pictish escort and a goodly number of the Red Slayers, the king’s bodyguard.”

“Yes,” said Volmana with some satisfaction. “That was your plan, Ascalante, but I accomplished it. I have kin high in the counsel of Grondar and it was a simple matter to indirectly persuade the king of Grondar to request the presence of Ka-nu. And of course, as Kull honors Ka-nu above all others, he must have a sufficient escort.”

The outlaw nodded.

“Good. I have at last managed, through Gromel, to corrupt an officer of the Red Guard. This man will march his men away from the royal bedroom tonight just before midnight, on a pretext of investigating some suspicious noise or the like. The various sentries will have been disposed of. We will be waiting, we five, and sixteen desperate rogues of mine who I have summoned from the hills and who now hide in various parts of the city. Twenty-one against one—”

He laughed. Gromel nodded, Volmana grinned, Kaanuub turned pale; Ridondo smote his hands together and cried out ringingly:

“By Valka, they will remember this night, who strike the golden strings! The fall of the tyrant, the death of the despot—what songs I shall make!”

His eyes burned with a wild fanatical light and the others regarded him dubiously, all save Ascalante who bent his head to hide a grin. Then the outlaw rose suddenly.

“Enough! Get back to your places and not by word, deed or look do you betray what is in your minds.” He hesitated, eyeing Kaanuub. “Baron, your white face will betray you. If Kull comes to you and looks into your eyes with those icy grey eyes of his, you will collapse. Get you out to your country estate and wait until we send for you. Four are enough.”

Kaanuub almost collapsed then, from a reaction of joy; he left babbling incoherencies. The rest nodded to the outlaw and departed.

Ascalante stretched himself like a great cat and grinned. He called for a slave and one came, a somber evil looking fellow whose shoulders bore the scars of the brand that marks thieves.

“Tomorrow,” quoth Ascalante, taking the cup offered him, “I come into the open and let the people of Valusia feast their eyes upon me. For months now, ever since the Rebel Four summoned me from my mountains, I have been cooped in like a rat—living in the very heart of my enemies, hiding away from the light in the daytime, skulking masked through dark alleys and darker corridors at night. Yet I have accomplished what those rebellious lords could not. Working through them and through other agents, many of whom have never seen my face, I have honeycombed the empire with discontent and corruption. I have bribed and subverted officials, spread sedition among the people—in short, I, working in the shadows, have paved the downfall of the king who at the moment sits throned in the sun. Ah, my friend, I had almost forgotten that I was a statesman before I was an outlaw, until Kaanuub and Volmana sent for me.”

“You work with strange comrades,” said the slave.

“Weak men, but strong in their ways,” lazily answered the outlaw. “Volmana—a shrewd man, bold, audacious, with kin in high places—but poverty stricken, and his barren estates loaded with debts. Gromel—a ferocious beast, strong and brave as a lion, with considerable influence among the soldiers, but otherwise useless—lacking the necessary brains. Kaanuub, cunning in his low way and full of petty intrigue, but otherwise a fool and a coward—avaricious but possessed of immense wealth, which has been essential in my schemes. Ridondo, a mad poet, full of hare-brained schemes—brave but flighty. A prime favorite with the people because of his songs which tear out their heart-strings. He is our best bid for popularity, once we have achieved our design. I am the power that has welded these men, useless without me.”

“Who mounts the throne, then?”

“Kaanuub, of course—or so he thinks! He has a trace of royal blood in him—the old dynasty, the blood of that king whom Kull killed with his bare hands. A bad mistake of the present king. He knows there are men who still boast descent from the old dynasty but he lets them live. So Kaanuub plots for the throne. Volmana wishes to be reinstated in favor, as he was under the old regime, so that he may lift his estate and title to their former grandeur. Gromel hates Kelka, commander of the Red Slayers, and thinks he should have that position. He wishes to be commander of all Valusia’s armies. As to Ridondo—bah! I despise the man and admire him at the same time. He is your true idealist. He sees in Kull, an outlander and a barbarian, merely a rough footed, red handed savage who has come out of the sea to invade a peaceful and pleasant land. He already idolizes the king Kull slew, forgetting the rogue’s vile nature. He forgets the inhumanities under which the land groaned during his reign, and he is making the people forget. Already they sing ‘The Lament for the King’ in which Ridondo lauds the saintly villain and vilifies Kull as ‘that black hearted savage’—Kull laughs at these songs and indulges Ridondo, but at the same time wonders why the people are turning against him.”

“But why does Ridondo hate Kull?”

“Because he is a poet, and poets always hate those in power, and turn to dead ages for relief in dreams. Ridondo is a flaming torch of idealism and he sees himself as a hero, a stainless knight, which he is, rising to overthrow the tyrant.”

“And you?”

Ascalante laughed and drained the goblet. “I have ideas of my own. Poets are dangerous things, because they believe what they sing—at the time. Well, I believe what I think. And I think Kaanuub will not hold the throne seat overlong. A few months ago I had lost all ambitions save to waste the villages and the caravans as long as I lived. Now, well—now we shall see.”

A room strangely barren in contrast to the rich tapestries on the walls and the deep carpets on the floor. A small writing table, behind which sat a man. This man would have stood out in a crowd of a million. It was not so much because of his unusual size, his height and great shoulders, though these features lent to the general effect. But his face, dark and immobile, held the gaze and his narrow grey eyes beat down the wills of the onlookers by their icy magnetism. Each movement he made, no matter how slight, betokened steel spring muscles and brain knit to those muscles with perfect coordination. There was nothing deliberate or measured about his motions—either he was perfectly at rest—still as a bronze statue, or else he was in motion, with that cat-like quickness which blurred the sight that tried to follow his movements. Now this man rested his chin on his fists, his elbows on the writing table, and gloomily eyed the man who stood before him. This man was occupied in his own affairs at the moment, for he was tightening the laces of his breast-plate. Moreover he was abstractedly whistling—a strange and unconventional performance, considering that he was in the presence of a king.

“Brule,” said the king, “this matter of statecraft wearies me as all the fighting I have done never did.”

“A part of the game, Kull,” answered Brule. “You are king—you must play the part.”

“I wish that I might ride with you to Grondar,” said Kull enviously. “It seems ages since I had a horse between my knees—but Tu says that affairs at home require my presence. Curse him!

“Months and months ago,” he continued with increasing gloom, getting no answer and speaking with freedom, “I overthrew the old dynasty and seized the throne of Valusia—of which I had dreamed ever since I was a boy in the land of my tribesmen. That was easy. Looking back now, over the long hard path I followed, all those days of toil, slaughter and tribulation seem like so many dreams. From a wild tribesman in Atlantis, I rose, passing through the galleys of Lemuria—a slave for two years at the oars—then an outlaw in the hills of Valusia—then a captive in her dungeons—a gladiator in her arenas—a soldier in her armies—a commander—a king!

“The trouble with me, Brule, I did not dream far enough. I always visualized merely the seizing of the throne—I did not look beyond. When king Borna lay dead beneath my feet, and I tore the crown from his gory head, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. From there, it has been a maze of illusions and mistakes. I prepared myself to seize the throne—not to hold it.

“When I overthrew Borna, then people hailed me wildly—then I was The Liberator—now they mutter and stare blackly behind my back—they spit at my shadow when they think I am not looking. They have put a statue of Borna, that dead swine, in the Temple of the Serpent and people go and wail before him, hailing him as a saintly monarch who was done to death by a red handed barbarian. When I led her armies to victory as a soldier, Valusia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner—now she cannot forgive me.

“And now, in the Temple of the Serpent, there come to burn incense to Borna’s memory, men whom his executioners blinded and maimed, fathers whose sons died in his dungeons, husbands whose wives were dragged into his seraglio— Bah! Men are all fools.”

“Ridondo is largely responsible,” answered the Pict, drawing his sword belt up another notch. “He sings songs that make men mad. Hang him in his jester’s garb to the highest tower in the city. Let him make rhymes for the vultures.”

Kull shook his lion head. “No, Brule, he is beyond my reach. A great poet is greater than any king. He hates me, yet I would have his friendship. His songs are mightier than my sceptre, for time and again he has near torn the heart from my breast when he chose to sing for me. I will die and be forgotten, his songs will live forever.”

The Pict shrugged his shoulders. “As you like; you are still king, and the people cannot dislodge you. The Red Slayers are yours to a man, and you have all Pictland behind you. We are barbarians, together, even if we have spent most of our lives in this land. I go, now. You have naught to fear save an attempt at assassination, which is no fear at all, considering the fact that you are guarded night and day by a squad of the Red Slayers.”

Kull lifted his hand in a gesture of farewell and the Pict clanked out the room.

Now another man wished his attention, reminding Kull that a king’s time was never his own.

This man was a young noble of the city, one Seno val Dor. This famous young swordsman and reprobate presented himself before the king with the plain evidence of much mental perturbation. His velvet cap was rumpled and as he dropped it to the floor when he kneeled, the plume drooped miserably. His gaudy clothing showed stains as if in his mental agony he had neglected his personal appearance for some time.

“King, lord king,” he said in tones of deep sincerity. “If the glorious record of my family means anything to your majesty, if my own fealty means anything, for Valka’s sake, grant my request.”

“Name it.”

“Lord king, I love a maiden—without her I cannot live. Without me, she must die. I cannot eat, I cannot sleep for thinking of her. Her beauty haunts me day and night—the radiant vision of her divine loveliness—”

Kull moved restlessly. He had never been a lover.

“Then in Valka’s name, marry her!”

“Ah,” cried the youth, “there’s the rub. She is a slave, Ala by name, belonging to one Volmana, count of Karaban. It is on the black books of Valusian law that a noble cannot marry a slave. It has always been so. I have moved high heaven and get only the same reply. ‘Noble and slave can never wed.’ It is fearful. They tell me that never in the history of the empire before has a nobleman wanted to marry a slave! What is that to me? I appeal to you as a last resort!”

“Will not this Volmana sell her?”

“He would, but that would hardly alter the case. She would still be a slave and a man cannot marry his own slave. Only as a wife I want her. Any other way would be hollow mockery. I want to show her to all the world, rigged out in the ermine and jewels of val Dor’s wife! But it cannot be, unless you can help me. She was born a slave, of a hundred generations of slaves, and slave she will be as long as she lives and her children after her. And as such she cannot marry a freeman.”

“Then go into slavery with her,” suggested Kull, eyeing the youth narrowly.

“This I desired,” answered Seno, so frankly that Kull instantly believed him. “I went to Volmana and said: ‘You have a slave whom I love; I wish to wed her. Take me, then, as your slave so that I may be ever near her.’ He refused with horror; he would sell me the girl, or give her to me but he would not consent to enslave me. And my father has sworn on the unbreakable oath to kill me if I should so degrade the name of val Dor as to go into slavery. No, lord king, only you can help us.”

Kull summoned Tu and laid the case before him. Tu, chief councillor, shook his head. “It is written in the great iron bound books, even as Seno has said. It has ever been the law, and it will always be the law. A noble may not mate with a slave.”

“Why may I not change that law?” queried Kull.

Tu laid before him a tablet of stone whereon the law was engraved.

“For thousands of years this law has been—see, Kull, on the stone it was carved by the primal law makers, so many centuries ago a man might count all night and still not number them all. Neither you, nor any other king, may alter it.”

Kull felt suddenly the sickening, weakening feeling of utter helplessness which had begun to assail him of late. Kingship was another form of slavery, it seemed to him—he had always won his way by carving a path through his enemies with his great sword—how could he prevail against solicitous and respectful friends who bowed and flattered and were adamant against anything new, or any change—who barricaded themselves and their customs with traditions and antiquity and quietly defied him to change—anything?

“Go,” he said with a weary wave of his hand. “I am sorry. But I cannot help you.”

Seno val Dor wandered out of the room, a broken man, if hanging head and bent shoulders, dull eyes and dragging steps mean anything.

A cool wind whispered through the green woodlands. A silver thread of a brook wound among great tree boles, whence hung large vines and gayly festooned creepers. A bird sang and the soft late summer sunlight was sifted through the interlocking branches to fall in gold and blackvelvet patterns of shade and light on the grass covered earth. In the midst of this pastoral quietude, a little slave girl lay with her face between her soft white arms, and wept as if her little heart would break. The bird sang but she was deaf; the brook called her but she was dumb; the sun shone but she was blind—all the universe was a black void in which only pain and tears were real.

So she did not hear the light footfall nor see the tall broad shouldered man who came out of the bushes and stood above her. She was not aware of his presence until he knelt and lifted her, wiping her eyes with hands as gentle as a woman’s.

The little slave girl looked into a dark immobile face, with cold narrow grey eyes which just now were strangely soft. She knew this man was not a Valusian from his appearance, and in these troublous times it was not a good thing for little slave girls to be caught in the lonely woods by strangers, especially foreigners, but she was too miserable to be afraid and besides the man looked kind.

“What’s the matter, child?” he asked and because a woman in extreme grief is likely to pour her sorrows out to anyone who shows interest and sympathy she whimpered: “Oh, sir, I am a miserable girl! I love a young nobleman—”

“Seno val Dor?”

“Yes, sir.” She glanced at him in surprize. “How did you know? He wishes to marry me and today having striven in vain elsewhere for permission, he went to the king himself. But the king refused to aid him.”

A shadow crossed the stranger’s dark face. “Did Seno say the king refused?”

“No—the king summoned the chief councillor and argued with him awhile, but gave in. Oh,” she sobbed, “I knew it would be useless! The laws of Valusia are unalterable! No matter how cruel or unjust! They are greater than the king.”

The girl felt the muscles of the arms supporting her swell and harden into great iron cables. Across the stranger’s face passed a bleak and hopeless expression.

“Aye,” he muttered, half to himself, “the laws of Valusia are greater than the king.”

Telling her troubles had helped her a little and she dried her eyes. Little slave girls are used to troubles and to suffering, though this one had been unusually kindly used all her life.

“Does Seno hate the king?” asked the stranger.

She shook her head. “He realizes the king is helpless.”

“And you?”

“And I what?”

“Do you hate the king?”

Her eyes flared—shocked. “I! Oh sir, who am I, to hate the king? Why, why, I never thought of such a thing.”

“I am glad,” said the man heavily. “After all, little one, the king is only a slave like yourself, locked with heavier chains.”

“Poor man,” she said, pityingly though not exactly understanding, then she flamed into wrath. “But I do hate the cruel laws which the people follow! Why should laws not change? Time never stands still! Why should people today be shackled by laws which were made for our barbarian ancestors thousands of years ago—” she stopped suddenly and looked fearfully about.

“Don’t tell,” she whispered, laying her head in an appealing manner on her companion’s iron shoulder. “It is not fit that a woman, and a slave girl at that, should so unashamedly express herself on such public matters. I will be spanked if my mistress or my master hears of it!”

The big man smiled. “Be at ease, child. The king himself would not be offended at your sentiments; indeed I believe that he agrees with you.”

“Have you seen the king?” she asked, her childish curiosity overcoming her misery for the moment.

“Often.”

“And is he eight feet tall,” she asked eagerly, “and has he horns under his crown, as the common people say?”

“Scarcely,” he laughed. “He lacks nearly two feet of answering your description as regards height; as for size he might be my twin brother. There is not an inch difference in us.”

“Is he as kind as you?”

“At times; when he is not goaded to frenzy by a statecraft which he cannot understand and by the vagaries of a people which can never understand him.”

“Is he in truth a barbarian?”

“In very truth; he was born and spent his early boyhood among the heathen barbarians who inhabit the land of Atlantis. He dreamed a dream and fulfilled it. Because he was a great fighter and a savage swordsman, because he was crafty in actual battle, because the barbarian mercenaries in Valusian armies loved him, he became king. Because he is a warrior and not a politician, because his swordsmanship helps him now not at all, his throne is rocking beneath him.”

“And he is very unhappy.”

“Not all the time,” smiled the big man. “Sometimes when he slips away alone and takes a few hours holiday by himself among the woods, he is almost happy. Especially when he meets a pretty girl like—”

The girl cried out in sudden terror, slipping to her knees before him: “Oh, sire, sire, have mercy! I did not know—you are the king!”

“Don’t be afraid.” Kull knelt beside her again and put an arm about her, feeling her trembling from head to foot. “You said I was kind—”

“And so you are, sire,” she whispered weakly. “I—I thought you were a human tiger, from what men said, but you are kind and tender—b-but—you are k-king and I—”

Suddenly in a very agony of confusion and embarrassment, she sprang up and fled, vanishing instantly. The overcoming realization that the king, whom she had only dreamed of seeing at a distance some day, was actually the man to whom she had told her pitiful woes, overcame her and filled her with an abasement and embarrassment which was an almost physical terror.

Kull sighed and rose. The affairs of the palace were calling him back and he must return and wrestle with problems concerning the nature of which he had only the vaguest idea and concerning the solving of which he had no idea at all.

Through the utter silence which shrouded the corridors and halls of the palace, fourteen figures stole. Their stealthy feet, cased in soft leather shoes, made no sound either on thick carpet or bare marble tile. The torches which stood in niches along the halls gleamed redly on bared dagger, broad sword blade and keen edged axe.

“Easy, easy all!” hissed Ascalante, halting for a moment to glance back at his followers. “Stop that cursed loud breathing, whoever it is! The officer of the night guard has removed all the guards from these halls, either by direct order or by making them drunk, but we must be careful. Lucky it is for us that those cursed Picts—the lean wolves—are either revelling at the consulate or riding to Grondar. Hist! back—here come the guard!”

They crowded back behind a huge pillar which might have hidden a whole regiment of men, and waited. Almost immediately ten men swung by; tall brawny men, in red armor, who looked like iron statues. They were heavily armed and the faces of some showed a slight uncertainty. The officer who led them was rather pale. His face was set in hard lines and he lifted a hand to wipe sweat from his brow as the guard passed the pillar where the assassins hid. He was young and this betraying of a king came not easy to him.

They clanked by and passed on up the corridor.

“Good!” chuckled Ascalante. “He did as I bid; Kull sleeps unguarded! Haste, we have work to do! If they catch us killing him, we are undone, but a dead king is easy to make a mere memory. Haste!”

“Aye haste!” cried Ridondo.

They hurried down the corridor with reckless speed and stopped before a door.

“Here!” snapped Ascalante. “Gromel—break me open this door!”

The giant launched his mighty weight against the panel. Again—this time there was a rending of bolts, a crash of wood and the door staggered and burst inward.

“In!” shouted Ascalante, on fire with the spirit of murder.

“In!” roared Ridondo. “Death to the tyrant—”

They halted short—Kull faced them—not a naked Kull, roused out of deep sleep, mazed and unarmed to be butchered like a sheep, but a Kull wakeful and ferocious, partly clad in the armor of a Red Slayer, with a long sword in his hand.

Kull had risen quietly a few minutes before, unable to sleep. He had intended to ask the officer of the guard into his room to converse with him awhile, but on looking through the spy-hole of the door, had seen him leading his men off. To the suspicious brain of the barbarian king had leaped the assumption that he was being betrayed. He never thought of calling the men back, because they were supposedly in the plot too. There was no good reason for this desertion. So Kull had quietly and quickly donned the armor he kept at hand, nor had he completed this act when Gromel first hurtled against the door.

For a moment the tableau held—the four rebel noblemen at the door and the ten wild desperate outlaws crowding close behind them—held at bay by the terrible-eyed silent giant who stood in the middle of the royal bedroom, sword at the ready.

Then Ascalante shouted: “In! And slay him! He is one to fourteen and he has no helmet!”

True; there had been lack of time to put on the helmet, nor was there now time to snatch the great shield from where it hung on the wall. Be that as it may, Kull was better protected than any of the assassins except Gromel and Volmana who were in full armor, with their vizors closed.

With a yell that rang to the roof, the killers flooded into the room. First of all was Gromel. He came in like a charging bull, head down, sword low for the disembowelling thrust. And Kull sprang to meet him like a tiger charging a bull, and all the king’s weight and mighty strength went into the arm that swung the sword. In a whistling arc the great blade flashed through the air to crash down on the commander’s helmet. Blade and helmet clashed and flew to pieces together and Gromel rolled lifeless on the floor, while Kull bounded back, gripping the bladeless hilt.

“Gromel!” he snarled as the shattered helmet disclosed the shattered head, then the rest of the pack were upon him. He felt a dagger point rake along his ribs and flung the wielder aside with a swing of his great left arm. He smashed his broken hilt square between another’s eyes and dropped him senseless and bleeding to the floor.

“Watch the door, four of you!” screamed Ascalante, dancing about the edge of that whirlpool of singing steel, for he feared Kull, with his great weight and speed, might smash through their midst and escape. Four rogues drew back and ranged themselves before the single door. And in that instant Kull leaped to the wall and tore therefrom an ancient battle axe which had hung there for possibly a hundred years.

Back to the wall he faced them for a moment, then leaped among them. No defensive fighter was Kull! He always carried the fight to the enemy. A sweep of the axe dropped an outlaw to the floor with a severed shoulder—the terrible back-hand stroke crushed the skull of another. A sword shattered against his breast-plate—else he had died. His concern was to protect his uncovered head and the spaces between breast plate and back plate—for Valusian armor was intricate and he had had no time to fully arm himself. Already he was bleeding from wounds on the cheek and the arms and legs, but so swift and deadly he was, and so much the fighter that even with the odds so greatly on their side, the assassins hesitated to leave an opening. Moreover their own numbers hampered them.

For one moment they crowded him savagely, raining blows, then they gave back and ringed him, thrusting and parrying—a couple of corpses on the floor gave mute evidence of the unwisdom of their first plan.

“Knaves!” screamed Ridondo in a rage, flinging off his slouch cap, his wild eyes glaring. “Do ye shrink from the combat? Shall the despot live? Out on it!”

He rushed in, thrusting viciously; but Kull, recognizing him, shattered his sword with a tremendous short chop and, with a push, sent him reeling back to sprawl on the floor. The king took in his left arm the sword of Ascalante and the outlaw only saved his life by ducking Kull’s axe and bounding backward. One of the hairy bandits dived at Kull’s legs hoping to bring him down in that manner, but after wrestling for a brief instant at what seemed a solid iron tower, he glanced up just in time to see the axe falling, but not in time to avoid it. In the interim one of his comrades had lifted a sword with both hands and hewed downward with such downright sincerity that he cut through Kull’s shoulder plate on the left side, and wounded the shoulder beneath. In an instant the king’s breast plate was full of blood.

Volmana, flinging the attackers to right and left in his savage impatience, came ploughing through and hacked savagely at Kull’s unprotected head. Kull ducked and the sword whistled above, shaving off a lock of hair—ducking the blows of a dwarf like Volmana is difficult for a man of Kull’s height.

Kull pivoted on his heel and struck from the side, as a wolf might leap, in a wide level arc—Volmana dropped with his whole left side caved in and the lungs gushing forth.

“Volmana!” Kull spoke the word rather breathlessly. “I’d know that dwarf in Hell—”

He straightened to defend himself from the maddened rush of Ridondo who charged in wild and wide open, armed only with a dagger. Kull leaped back, axe high.

“Ridondo!” his voice rang sharply. “Back! I would not harm you—”

“Die, tyrant!” screamed the mad minstrel, hurling himself headlong on the king. Kull delayed the blow he was loath to deliver until it was too late. Only when he felt the bite of steel in his unprotected side did he strike, in a frenzy of blind desperation.

Ridondo dropped with a shattered skull and Kull reeled back against the wall, blood spurting through the fingers which gripped his wounded side.

“In, now, and get him!” yelled Ascalante, preparing to lead the attack.

Kull placed his back to the wall and lifted his axe. He made a terrible and primordial picture. Legs braced far apart, head thrust forward, one red hand clutching at the wall for support, the other gripping the axe on high, while the ferocious features were frozen in a death snarl of hate, and the icy eyes blazed through the mist of blood which veiled them. The men hesitated; the tiger might be dying but he was still capable of dealing death.

“Who dies first?” snarled Kull through smashed and bloody lips.

Ascalante leaped as a wolf leaps—halted almost in mid-air with the unbelievable speed which characterized him, and fell prostrate to avoid the death that was hissing toward him in the form of a red axe. He frantically whirled his feet out of the way and rolled clear just as Kull recovered from his missed blow and struck again—this time the axe sank four inches into the polished wood floor close to Ascalante’s revolving legs.

Another desperado rushed at this instant, followed half heartedly by his fellows. The first villain had figured on reaching Kull and killing him before he could get his axe out of the floor, but he miscalculated the king’s speed, or else he started his rush a second too late. At any rate the axe lurched up and crashed down and the rush halted abruptly as a reddened caricature of a man was catapulted back against their legs.

At that moment a hurried clanking of feet sounded down the hall and the rogues in the door raised a shout: “Soldiers coming!”

Ascalante cursed and his men deserted him like rats leaving a sinking ship. They rushed out into the hall—or limped, splattering blood—and down the corridor a hue and cry was raised, and pursuit started.

Save for the dead and dying men on the floor, Kull and Ascalante stood alone in the royal bed room. Kull’s knees were buckling and he leaned heavily against the wall, watching the outlaw with the eyes of a dying wolf.

“All seems to be lost, particularly honor,” he murmured. “However the king is dying on his feet—and—” whatever other cogitation might have passed through his mind is not known for at that moment he ran lightly at Kull just as the king was employing his axe arm to wipe the blood from his half blind eyes. A man with a sword at the ready can thrust quicker than a wounded man out of position can strike with an axe that weighs his weary arm like lead.

But even as Ascalante began his thrust, Seno val Dor appeared at the door and flung something through the air which glittered, sang and ended its flight in Ascalante’s throat. The outlaw staggered, dropped his sword and sank to the floor at Kull’s feet, flooding them with the flow of a severed jugular—mute witness that Seno’s war-skill included knife throwing as well. Kull looked down bewilderedly at the dead outlaw and Ascalante’s dead eyes stared back in seeming mockery, as if the owner still maintained the futility of kings and outlaws, of plots and counter-plots.

Then Seno was supporting the king, the room was flooded with men-at-arms in the uniform of the great val Dor family and Kull realized that a little slave girl was holding his other arm.

“Kull, Kull, are you dead?” val Dor’s face was very white.

“Not yet,” the king spoke huskily. “Staunch this wound in my left side—if I die ’twill be from it; ’tis deep but the rest are not mortal—Ridondo wrote me a deathly song there! Cram stuff into it for the present—I have work to do.”

They obeyed wonderingly and as the flow of blood ceased, Kull though literally bled white already, felt some slight access of strength. The palace was fully aroused now. Court ladies, lords, men-at-arms, councillors, all swarmed about the place babbling. The Red Slayers were gathering, wild with rage, ready for anything, jealous of the fact that others had aided their king. Of the young officer who had commanded the door guard, he had slipped away in the darkness and neither then nor later was he in evidence, though earnestly sought after.

Kull, still keeping stubbornly to his feet, grasping his bloody axe with one hand and Seno’s shoulder with another singled out Tu, who stood wringing his hands and ordered: “Bring me the tablet whereon is engraved the law concerning slaves.”

“But lord king—”

“Do as I say!” howled Kull, lifting the axe and Tu scurried to obey.

As he waited and the court women flocked about him, dressing his wounds and trying gently but vainly to pry his iron fingers from about the bloody axe handle, Kull heard Seno’s breathless tale.

“—Ala heard Kaanuub and Volmana plotting—she had stolen into a little nook to cry over her—our troubles, and Kaanuub came, on his way to his country estate. He was shaking with terror for fear plans might go awry and he made Volmana go over the plot with him again before he left, so he might know there was no flaw in it.

“He did not leave until it was late, and then Ala stole away and came to me. But it is a long way from Volmana’s city house to the house of val Dor, a long way for a little girl to walk, and though I gathered my men and came instantly, we almost arrived too late.”

Kull gripped his shoulder.

“I will not forget.”

Tu entered with the law tablet, laying it reverently on the table.

Kull shouldered aside all who stood near him and stood up alone.

“Hear, people of Valusia,” he exclaimed, upheld by the wild beast vitality which was his, fired from within by a strength which was more than physical. “I stand here—the king. I am wounded almost unto death, but I have survived mass wounds.

“Hear you! I am weary of this business! I am no king but a slave! I am hemmed in by laws, laws, laws! I cannot punish malefactors nor reward my friends because of law—custom—tradition! By Valka, I will be king in fact as well as in name!

“Here stand the two who have saved my life! Henceforward they are free to marry, to do as they like!”

Seno and Ala rushed into each other’s arms with a glad cry.

“But the law!” screamed Tu.

“I am the law!” roared Kull, swinging up his axe; it flashed downward and the stone tablet flew into a hundred pieces. The people clenched their hands in horror, waiting dumbly for the sky to fall.

Kull reeled back, eyes blazing. The room whirled to his dizzy gaze.

“I am king, state and law!” he roared, and seizing the wand-like sceptre which lay near, he broke it in two and flung it from him. “This shall be my sceptre!” The red axe was brandished aloft, splashing the pallid nobles with drops of blood. Kull gripped the slender crown with his left hand and placed his back against the wall. Only that support kept him from falling but in his arms was still the strength of lions.

“I am either king or corpse!” he roared, his corded muscles bulging, his terrible eyes blazing. “If you like not my kingship—come and take this crown!”

The corded left arm held out the crown, the right gripping the menacing axe above it.

“By this axe I rule! This is my sceptre! I have struggled and sweated to be the puppet king you wished me to be—to king it your way. Now I use mine own way! If you will not fight, you shall obey! Laws that are just shall stand; laws that have outlived their times I shall shatter as I shattered that one! I am king!”

Slowly the pale faced noblemen and frightened women knelt, bowing in fear and reverence to the blood stained giant who towered above them with his eyes ablaze.

“I am king!”