Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

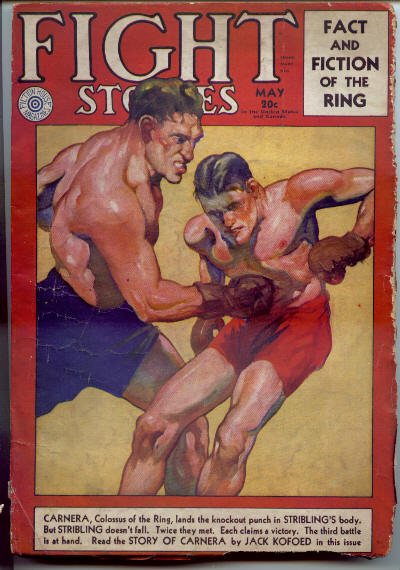

Published in Fight Stories, Vol. 3, No. 12 (May 1931).

The Sea Girl hadn’t been docked in Tampico more’n a few hours when I got into a argument with a big squarehead off a tramp steamer. I forget what the row was about—sailing vessels versus steam, I think. Anyway, the discussion got so heated he took a swing at me. He musta weighed nearly three hundred pounds, but he was meat for me. I socked him just once and he went to sleep under the ruins of a table.

As I turned back to my beer mug in high disgust, I noticed that a gang of fellers which had just come in was gawping at me in wonder. They was cow-punchers, in from the ranges, all white men, tall, hard and rangy, with broad-brimmed hats, leather chaps, big Mexican spurs, guns an’ everything; about ten of them, altogether.

“By the gizzard uh Sam Bass,” said the tallest one, “I plumb believe we’ve found our man, hombres. Hey, pardner, have a drink! Come on—set down at this here table. I wanta talk to you.”

So we all set down and, while we was drinking some beer, the tall cow-puncher glanced admiringly at the squarehead which was just coming to from the bar-keep pouring water on him, and the cow-puncher said:

“Lemme introduce us: we’re the hands of the Diamond J—old Bill Dornley’s ranch, way back up in the hills. I’m Slim, and these is Red, Tex, Joe, Yuma, Buck, Jim, Shorty, Pete and the Kid. We’re in town for a purpose, pardner, which is soon stated.

“Back up in the hills, not far from the Diamond J, is a minin’ company, and them miners has got the fightin’est buckaroo in these parts. They’re backin’ him agin all comers, and I hates to say what he’s did to such Diamond J boys as has locked horns with him. Them miners has got a ring rigged up in the hills where this gent takes on such as is wishful to mingle with him, but he ain’t particular. He knocked out Joe, here, in that ring, but he plumb mopped up a mesquite flat with Red, which challenged him to a rough-and-tumble brawl with bare fists. He’s a bear-cat, and the way them miners is puttin’ on airs around us boys is somethin’ fierce.

“We’ve found we ain’t got no man on the ranch which can stand up to that grizzly, and so we come into town to find some feller which could use his fists. Us boys is more used to slingin’ guns than knuckles. Well, the minute I seen you layin’ down that big Swede, I says to myself, I says, ‘Slim, there’s your man!’

“How about it, amigo? Will you mosey back up in the hills with us and flatten this big false alarm? We aim to bet heavy, and we’ll make it worth yore while.”

“And how far is this here ranch?” I asked.

“ ’Bout a day’s ride, hossback—maybe a little better’n that.”

“That’s out,” I decided. “I can’t navigate them four-legged craft. I ain’t never been on a horse more’n three or four times, and I ain’t figgerin’ on repeatin’ the experiment.”

“Well,” said Slim, “we’ll get hold of a auteymobeel and take you out in style.”

“No,” I said, “I don’t believe I’ll take you up; I wanta rest whilst I’m in port. I’ve had a hard voyage; we run into nasty weather and had one squall after another. Then the Old Man picked up a substitute second mate in place of our regular mate which is in jail in Melbourne, and this new mate and me has fought clean across the Pacific, from Melbourne to Panama, where he give it up and quit the ship.”

The cow-punchers all started arguing at the same time, but Slim said:

“Aw, that’s all right boys; I reckon the gent knows what he wants to do. We can find somebody else, I reckon. No hard feelin’s. Have another drink.”

I kinda imagined he had a mysterious gleam in his eye, and it looked like to me that when he motioned to the bartender, he made some sort of a signal; but I didn’t think nothing about it. The bar-keep brought a bottle of hard licker, and Slim poured it, saying: “What did you say yore name was, amigo?”

“Steve Costigan, a. b. on the sailing vessel Sea Girl,” I answered. “I want you fellers to hang around and meet Bill O’Brien and Mushy Hanson, my shipmates, they’ll be around purty soon with my bulldog Mike. I’m waitin’ for ’em. Say, this stuff tastes funny.”

“That’s just high-grade tequila,” said Slim. “Costigan, I shore wish you’d change yore mind about goin’ out to the ranch and fightin’ for us.”

“No chance,” said I. “I crave peace and quiet. . . . Say, what the heck. . . ?”

I hadn’t took but one nip of that funny-tasting stuff, but the bar-room had begun to shimmy and dance. I shook my head to clear it and saw the cowboys, kinda misty and dim, they had their heads together, whispering, and one of ’em said, kinda low-like: “He’s fixin’ to pass out. Grab him!”

At that, I give a roar of rage and heaved up, upsetting the table and a couple of cow-hands.

“You low-down land-sharks,” I roared. “You doped my grog!”

“Grab him, boys!” yelled Slim, and three or four nabbed me. But I throwed ’em off like chaff and caught Slim on the chin with a clout that sprawled him on the back of his neck. I socked Red on the nose and it spattered like a busted tomater, and at this instant Pete belted me over the head with a gun-barrel.

With a maddened howl, I turned on him, and he gasped, turned pale and dropped the gun for some reason or other. I sunk my left mauler to the wrist in his midriff, and about that time six or seven of them cow-punchers jumped on my neck and throwed me by sheer weight of man-power.

I got Yuma’s thumb in my mouth and nearly chawed it off, but they managed to sling some ropes around me, and the drug, from which I was already weak and groggy, took full effect about this time and I passed clean out.

I musta been out a long time. I kinda dimly remember a sensation of bumping and jouncing along, like I was in a car going over a rough road, and I remember being laid on a bunk and the ropes took off, but that’s all.

I was woke up by voices. I set up and cussed. I had a headache and a nasty taste in my mouth, and, feeling the back of my head, I found a bandage, which I tore off with irritation. Keel haul me! As if a scalp cut like that gun-barrel had give me needed dressing!

I was sitting on a rough bunk in a kinda small shack which was built of heavy planks. Outside I heered Slim talking:

“No, Miss Joan, I don’t dast let you in to look at him. He ain’t come to, I don’t reckon ’cause they ain’t no walls kicked outa the shack, yet; but he might come to hisself whilst you was in there, and they’s no tellin’ what he might do, even to you. The critter ain’t human, I’m tellin’ you, Miss Joan.”

“Well,” said a feminine voice, “I think it was just horrid of you boys to kidnap a poor ignorant sailor and bring him away off up here just to whip that miner.”

“Golly, Miss Joan,” said Slim, kinda like he was hurt, “if you got any sympathy to spend, don’t go wastin’ it on that gorilla. Us boys needs yore sympathy. I winked at the bar-keep for the dope when I ordered the drinks, and, when I poured the sailor’s, I put enough of it in his licker to knock out three or four men. It hit him quick, but he was wise to it and started sluggin’. With all them knockout drops in him, he near wrecked the joint! Lookit this welt on my chin—when he socked me I looked right down my own spine for a second. He busted Red’s nose flat, and you oughta see it this mornin’. Pete lammed him over the bean so hard he bent the barrel of his forty-five, but all it done was make Costigan mad. Pete’s still sick at his stummick from the sock the sailor give him. I tell you, Miss Joan, us boys oughta have medals pinned on us; we took our lives in our hands, though we didn’t know it at the start, and, if it hadn’t been for the dope, Costigan would have destroyed us all. If yore dad ever fires me, I’m goin’ to git a job with a circus, capturin’ tigers and things. After that ruckus, it oughta be a cinch.”

At this point, I decided to let folks know I was awake and fighting mad about the way I’d been treated, so I give a roar, tore the bunk loose from the wall and throwed it through the door. I heard the girl give a kind of scream, and then Slim pulled open what was left of the door and come through. Over his shoulder I seen a slim nice-looking girl legging it for the ranch-house.

“What you mean scarin’ Miss Joan?” snarled Slim, tenderly fingering a big blue welt on his jaw.

“I didn’t go to scare no lady,” I growled. “But in about a minute I’m goin’ to scatter your remnants all over the landscape. You think you can shanghai me and get away with it? I want a big breakfast and a way back to port.”

“You’ll git all the grub you want if you’ll agree to do like we says,” said Slim; “but you ain’t goin’ to git a bite till you does.”

“You’d keep a man from mess, as well as shanghai him, hey?” I roared. “Well, lemme tell you, you long-sparred, leather-rigged son of a sea-cock, I’m goin’ to—”

“You ain’t goin’ to do nothin’,” snarled Slim, whipping out a long-barreled gun and poking it in my face.

“You’re goin’ to do just what I says or get the daylight let through you—”

Having a gun shoved in my face always did enrage me. I knocked it out of his hand with one mitt, and him flat on his back with the other, and, jumping on his prostrate frame with a blood-thirsty yell of joy, I hammered him into a pulp.

His wild yells for help brought the rest of the crew on the jump, and they all piled on me for to haul me off. Well, I was the center of a whirlwind of fists, boots, and blood-curdling howls of pain and rage for some minutes, but they was just too many of them and they was too handy with them lassoes. When they finally had me hawg-tied again, the side wall was knocked clean out of the shack, the roof was sagging down and Joe, Shorty, Jim and Buck was out cold.

Slim, looking a lee-sore wreck, limped over and glared down at me with his one good eye whilst the other boys felt theirselves for broken bones and throwed water over the fallen gladiators.

“You snortin’ buffalo,” Slim snarled. “How I hones to kick yore ribs in! What do you say? Do you fight or stay tied up?”

The cook-shack was near and I could smell the bacon and eggs sizzling. I hadn’t eat nothing since dinner the day before and I was hungry enough to eat a raw sea lion.

“Lemme loose,” I growled. “I gotta have food. I’ll lick this miner for you, and when I’ve did that, I’m going to kick down your bunkhouse and knock the block offa every man, cook and steer on this fool ranch.”

“Boy,” said Slim with a grin, spitting out a loose tooth, “does you lick that miner, us boys will each give you a free swing at us. Come on—you’re loose now—let’s go get it.”

“Let’s send somebody over to the Bueno Oro Mine and tell them mavericks ’bout us gittin’ a slugger,” suggested Pete, trying to work back a thumb he’d knocked outa place on my jaw.

“Good idee,” said Slim. “Hey, Kid, ride over and tell ’em we got a man as can make hash outa their longhorn. Guess we can stage the scrap in about five days, hey, Sailor?”

“Five days my eye,” I grunted. “The Sea Girl sails day after tomorrow and I gotta be on her. Tell ’em to get set for the go this evenin’.”

“But, gee whiz!” expostulated Slim. “Don’t you want a few days to train?”

“If I was outa trainin’, five days wouldn’t help me none,” I said. “But I’m allus in shape. Lead on the mess table. I crave nutriment.”

Well, them boys didn’t hold no grudge at all account of me knocking ’em around. The Kid got on a broom-tailed bronc and cruised off across the hills, and the rest of us went for the cook-shack. Joe yelled after the Kid: “Look out for López the Terrible!” And they all laughed.

Well, we set down at the table and the cook brung aigs and bacon and fried steak and sour-dough bread and coffee and canned corn and milk till you never seen such a spread. I lay to and ate till they looked at me kinda bewildered.

“Hey!” said Slim, “ain’t you eatin’ too much for a tough scrap this evenin’?”

“What you cow-pilots know about trainin’?” I said. “I gotta keep up my strength. Gimme some more of them beans, and tell the cook to scramble me five or six more aigs and bring me in another stack of buckwheats. And say,” I added as another thought struck me, “who’s this here López you-all was jokin’ about?”

“By golly,” said Tex, “I thought you cussed a lot like a Texan. ‘You-all,’ huh? Where was you born?”

“Galveston,” I said.

“Zowie!” yelled Tex. “Put ’er there, pard; I aims for to triple my bets on you! López? Oh, he’s just a Mex bandit—handsome cuss, I’ll admit, and purty mean. He ranges around in them hills up there and he’s stole some of our stock and made a raid or so on the Bueno Oro. He’s allus braggin’ ’bout how he aims for to raid the Diamond J some day and ride off with Joan—that’s old Bill Dornley’s gal. But heck, he ain’t got the guts for that.”

“Not much he ain’t,” said Jim. “Say, I wish old Bill was at the ranch now, ’steada him and Miz Dornley visitin’ their son at Zacatlán. They’d shore enjoy the scrap this evenin’. But Miss Joan’ll be there, you bet.”

“Is she the dame I scared when I called you?” I asked Slim.

“Called me? Was you callin’ me?” said he. “Golly, I’d of thought a bull was in the old shack, only a bull couldn’t beller like that. Yeah, that was her.”

“Well,” said I, “tell her I didn’t go for to scare her. I just naturally got a deep voice from makin’ myself heard in gales at sea.”

Well, we finished breakfast and Slim says: “Now what you goin’ to do, Costigan? Us boys wants to help you train all we can.”

“Good,” I said. “Fix me up a bunk; nothing like a good long nap when trainin’ for a tough scrap.”

“All right,” said they. “We reckons you knows what you wants; while you git yore rest, we’ll ride over and lay some bets with the Bueno Oro mavericks.”

So they showed me where I couldst take a nap in their bunkhouse and I was soon snoozing. Maybe I should of kinda described the ranch. They was a nice big house, Spanish style, but made of stone, not ’dobe, and down to one side was the corrals, the cook-shack, the long bunkhouse where the cowboys stayed, and a few Mexican huts. But they wasn’t many Mexes working on the Diamond J. They’s quite a few ranches in Old Mexico owned and run altogether by white men. All around was big rolling country, rough ranges of sagebrush, mesquite, cactus and chaparral, sloping in the west to hills which further on became right good-sized mountains.

Well, I was woke up by the scent of victuals; the cook was fixing dinner. I sat up on the bunk and—lo, and behold—there was the frail they called Miss Joan in the door of the bunkhouse, staring at me wide-eyed like I was a sea horse or something.

I started to tell her I was sorry I scared her that morning, but when she seen I was awake she give a gasp and steered for the ranch-house under full sail.

I was bewildered and slightly irritated. I could see that she got a erroneous idee about me from listening to Slim’s hokum, and, having probably never seen a sailor at close range before, she thought I was some kind of a varmint.

Well, I realized I was purty hungry, having ate nothing since breakfast, so I started for the cook-shack and about that time the cow-punchers rode up, plumb happy and hilarious.

“Hot dawg!” yelled Slim. “Oh, baby, did them miners bite! They grabbed everything in sight and we has done sunk every cent we had, as well bettin’ our hosses, saddles, bridles and shirts.”

“And believe me,” snarled Red, tenderly fingering what I’d made outa his nose, and kinda hitching his gun prominently, “you better win!”

“Don’t go makin’ no grandstand plays at me,” I snorted. “If I can’t lick a man on my own inisheyative, no gun-business can make me do it. But don’t worry; I can flatten anything in these hills, includin’ you and all your relatives. Let’s get into that mess gallery before I clean starve.”

While we ate, Slim said all was arranged; the miners had knocked off work to get ready and the scrap would take place about the middle of the evening. Then the punchers started talking and telling me things they hadst did and seen, and of all the triple-decked, full-rigged liars I ever listened to, them was the beatenest. The Kid said onst he come onto a mountain lion and didn’t have no rope nor gun, so he caught rattlesnakes with his bare hands and tied ’em together and made a lariat and roped the lion and branded it, and he said how they was a whole breed of mountain lions in the hills with the Diamond J brand on ’em and the next time I seen one, if I would catch it and look on its flank, I would see it was so.

So I told them that once when I was cruising in the Persian Gulf, the wind blowed so hard it picked the ship right outa the water and carried it clean across Arabia and dropped it in the Mediterranean Sea; all the riggings was blown off, I said, and the masts outa her, so we caught sharks and hitched them to the bows and made ’em tow us into port.

Well, they looked kinda weak and dizzy then, and Slim said: “Don’t you want to work out a little to kinda loosen up your muscles?”

Well, I was still sore at them cow-wranglers for shanghaing me the way they done, so I grinned wickedly and said: “Yeah, I reckon I better; my muscles is purty stiff, so you boys will just naturally have to spar some with me.”

Well they looked kinda sick, but they was game. They brung out a battered old pair of gloves and first Joe sparred with me. Whilst they was pouring water on Joe they argued some about who was to spar with me next and they drawed straws and Slim was it.

“By golly,” said Slim looking at his watch, “I’d shore admire to box with you, Costigan, but it’s gettin’ about time for us to start dustin’ the trail for the Bueno Oro.”

“Heck, we got plenty uh time,” said Buck.

Slim glowered at him. “I reckon the foreman—which is me—knows what time uh day it is,” said Slim. “I says we starts for the mine. Miss Joan has done said she’d drive Costigan over in her car, and me and Shorty will ride with ’em. I kinda like to be close around Miss Joan when she’s out in the hills. You can’t tell; López might git it into his haid to make a bad play. You boys will foller on your broncs.”

Well, that’s the way it was. Joan was a mighty nice looking girl and she was very nice to me when Slim interjuced me to her, but I couldst see she was nervous being that close to me, and it offended me very much, though I didn’t show it none.

Slim set on the front seat with her, and me and Shorty on the back seat, and we drove over the roughest country I ever seen. Mostly they wasn’t no road at all, but Joan knowed the channel and didn’t need no chart to navigate it, and eventually we come to the mine.

The mine and some houses was up in the hills, and about half a mile from it, on a kind of a broad flat, the ring was pitched. Right near where the ring stood, was a narrow canyon, leading up through the hills. We had to leave the car close to the mine and walk the rest of the way, the edge of the flat being too rough to drive on.

They was quite a crowd at the ring, which was set up in the open. I notice that the Bueno Oro was run by white men same as the ranch. The miners was all big, tough-looking men in heavy boots, bearded and wearing guns, and they was a considerable crew of ’em. They was still more cow-punchers from all the ranches in the vicinity, a lean, hard-bit gang, with even more guns on them than the miners had. By golly, I never seen so many guns in one place in my life!

They was quite a few Mexicans watching, men and women, but Joan was the only white woman I seen. All the men took their hats off to her, and I seen she was quite a favorite among them rough fellers, some of which looked more like pirates than miners or cowboys.

Well the crowd set up a wild roar when they seen me, and Slim yelled: “Well, you mine-rasslin’ mavericks, here he is! I shudders to think what he’s goin’ to do to yore man.”

All the cow-punchers yipped jubilantly and all the miners yelled mockingly, and up come the skipper of the mine—the guy that done the managing of it—a fellow named Menly.

“Our man is in his tent getting on his togs, Slim,” said he. “Get your fighter ready—and we’d best be on the lookout. I’ve had a tip that López is in the hills close by. The mine’s unguarded. Everybody’s here. And while there’s no ore or money for him to swipe—we sent out the ore yesterday and the payroll hasn’t arrived yet—he could do a good deal of damage to the buildings and machinery if he wanted to.”

“We’ll watch out, you bet,” assured Slim, and steered me for what was to serve as my dressing room. They was two tents pitched one on each side of the ring, and they was our dressing rooms. Slim had bought a pair of trunks and ring shoes in Tampico, he said, and so I was rigged out shipshape.

As it happened, I was the first man in the ring. A most thunderous yell went up, mainly from the cow-punchers, and, at the sight of my manly physique, many began to pullout their watches and guns and bet them. The way them miners snapped up the wagers showed they had perfect faith in their man. And when he clumb in the ring a minute later they just about shook the hills with their bellerings. I glared and gasped.

“Snoots Leary or I’m a Dutchman!” I exclaimed.

“Biff Leary they call him,” said Slim which, with Tex and Shorty and the Kid, was my handler. “Does you know him?”

“Know him?” said I. “Say, for the first fourteen years of my life I spent most of my time tradin’ punches with him. They ain’t a back-alley in Galveston that we ain’t bloodied each other’s noses in. I ain’t seen him since we was just kids—I went to sea, and he went the other way. I heard he was mixin’ minin’ with fightin’. By golly, hadst I knowed this you wouldn’t of had to shanghai me.”

Well, Menly called us to the center of the ring for instructions and Leary gawped at me: “Steve Costigan, or I’m a liar! What you doin’ fightin’ for cow-wranglers? I thought you was a sailor.”

“I am, Snoots,” I said, “and I’m mighty glad for to see you here. You know, we ain’t never settled the question as to which of us is the best man. You’ll recollect in all the fights we had, neither of us ever really won; we’d generally fight till we was so give out we couldn’t lift our mitts, or else till somebody fetched a cop. Now we’ll have it out, once and for all!”

“Good!” said he, grinning like a ogre. “You’re purty much of a man, Steve, but I figger I’m more. I ain’t been swingin’ a sledge all this time for nothin’. And I reckon the nickname of ‘Biff’ is plenty descriptive.”

“You always was conceited, Biff,” I scowled. “Different from me. Do I go around tellin’ people how good I am? Not me; I don’t have to. They can tell by lookin’ at me that I’m about the best two-fisted man that ever walked a forecastle. Shake now and let’s come out fightin’.”

Well, the referee had been trying to give us instructions, but we hadn’t paid no attention to him, so now he muttered a few mutters under his breath and told us to get ready for the gong. Meanwhile the crowd was developing hydrophobia wanting us to get going. They’d got a camp chair for Miss Joan, but the men all stood up, banked solid around the ring so close their noses was nearly through the ropes, and all yelling like wolves.

“For cat’s sake, Steve,” said Slim as he crawled out of the ring, “don’t fail us. Leary looks even meaner than he done when he licked Red and Joe.”

I’ll admit Biff was a hard looking mug. He was five feet ten to my six feet, and he weighed 195 to my 190. He had shoulders as wide as a door, a deep barrel chest, huge fists and arms like a gorilla’s. He was hairy and his muscles swelled like iron all over him, miner’s style, and his naturally hard face hadst not been beautified by a broken nose and a cauliflower ear. Altogether, Biff looked like what he was—a rough and ready fighting man.

At the tap of the gong he come out of his corner like a typhoon, and I met him in the center of the ring. By sheer luck he got in the first punch—a smashing left hook to the head that nearly snapped my neck. The crowd went howling crazy, but I come back with a sledge-hammer right hook that banged on his cauliflower ear like a gunshot. Then we went at it hammer and tongs, neither willing to take a back step, just like we fought when we was kids.

He had a trick of snapping a left uppercut inside the crook of my arm and beating my right hook. He’d had that trick when we fought in the Galveston alleys, and he hadn’t forgot it. I never couldst get away from that peculiar smack. Again and again he snapped my head back with it—and I got a neck like iron, too; ain’t everybody can rock my head back on it.

He wasn’t neglecting his right either. In fact he was mighty fond of banging me on the ear with that hand. Meanwhile, I was ripping both hands to his liver, belly and heart, every now and then bringing up a left or right to his head. We slugged that round out without much advantage on either side, but just before the gong, one of them left uppercuts caught me square in the mouth and the claret started in streams.

“First blood, Steve,” grinned Biff as he turned to his corner.

Slim wiped off the red stuff and looked kinda worried.

“He’s hit you some mighty hard smacks, Steve,” said he.

I snorted. “Think I been pattin’ him? He’ll begin to feel them body smashes in a round or so. Don’t worry; I been waitin’ for this chance for years.”

At the tap of the gong for the second round we started right in where we left off. Biff come in like he aimed for to take me apart, but I caught him coming in with a blazing left hook to the chin. His eyes rolled, but he gritted his teeth and come driving in so hard he battered me back in spite of all I couldst do. His head was down, both arms flying, legs driving like a charging bull. He caught me in the belly with a right hook that shook me some, but I braced myself and stopped him in his tracks with a right uppercut to the head.

He grunted and heaved over a right swing that started at his knees, and I didn’t duck quick enough. It caught me solid but high, knocking me back into the ropes.

The miners roared with joy and the cow-punchers screamed in dismay, but I wasn’t hurt. With a supercilious sneer, I met Leary’s rush with a straight left which snapped his head right back between his shoulders and somehow missed a slungshot right uppercut which had all my beef behind it.

Biff hooked both hands hard to my head and shot his right under my heart, and I paid him back with a left to the midriff which brung a grunt outa him. I crashed an overhand right for his jaw but he blocked it and was short with a hard right swing. I went inside his left to blast away at his body with both hands in close, and he throwed both arms around me and smothered my punches.

We broke of ourselves before Menly couldst separate us, and I hooked both hands to Leary’s head, taking a hard drive between the eyes which made me see stars. We then stood head to head in the center of the ring and traded smashes till we was both dizzy. We didn’t hear the gong and Menly had to jump in and haul us apart and shove us toward our corners.

The crowd was plumb cuckoo by this time; the cowboys was all yelling that I won that round and the miners was swearing that it was Biff’s by a mile. I snickered at this argument, and I noticed Biff snort in disgust. I never go into no scrap figgering to win it on points. If I can’t knock the other sap stiff, he’s welcome to the decision. And I knowed Biff felt the same way.

Leary was in my corner for the next round before I was offa my stool, and he missed me with a most murderous right. I was likewise wild with a right, and Biff recovered his balance and tagged me on the chin with a left uppercut. Feeling kinda hemmed in, I went for him with a roar and drove him out into the center of the ring with a series of short, vicious rushes he couldn’t altogether stop.

I shook him to his heels with a left hook to the body and started a right hook for his head. Up flashed his left for that trick uppercut, and I checked my punch and dropped my right elbow to block. He checked his punch too and crashed a most tremendous right to my unguarded chin. Blood splattered and I went back on my heels, floundering and groggy, and Biff, wild for the kill and flustered by the yells, lost his head and plunged in wide open, flailing with both arms.

I caught him with a smashing left hook to the jaw and he rolled like a clipper in rough weather. I ripped a right under his heart and cracked a hard left to his ear, and he grabbed me like a grizzly and hung on, shaking his head to get rid of the dizziness. He was tough—plenty tough. By the time the referee had broke us, his head had plumb cleared and he proved it by giving a roar of rage and smacking me square on the nose with a punch that made the blood fly.

Again the gong found us slugging head-to-head. Slim and the boys was so weak and wilted from excitement they couldn’t hardly see straight enough to mop off the blood and give me a piece of lemon to suck.

Well, this scrap was to be to a finish and it looked like to me it wouldst probably last fifteen or twenty more rounds. I wasn’t tired or weakened any, and I knowed Biff was like a granite boulder—nearly as tough as me. I figgered on wearing him down with body punishment, but even I couldn’t wear down Biff Leary in a few shakes. Just like me, he won most of his fights by simply outlasting the other fellow.

Still, with a punch like both of us carried in each hand, anything might happen—and did, as it come about.

We opened the fourth like we had the others, and slugged our way through it, on even terms. Same way with the fifth, only in this I opened a gash on Biff’s temple and he split my ear. As we come up for the sixth, we both showed some wear and tear. One of my eyes was partly closed, I was bleeding at the mouth and nose, and from my cut ear; Biff had lost a tooth, had a deep cut on his temple, and his ribs on the left side was raw from my body punches.

But neither of us was weakening. We come together fast and Biff ripped my lip open with a savage left hook. His right glanced offa my head and again he tagged me with his left uppercut. I sunk my right deep in his ribs and we both shot our lefts. His started a fraction of a second before mine, and he beat me to the punch; his mitt biffed square in my already closing eye, and for a second the punch blinded me.

His right was coming behind his left, swinging from the floor with every ounce of his beef behind it. Wham! Square on the chin that swinging mauler tagged me, and it was like the slam of a sledge-hammer. I felt my feet fly out from under me, and the back of my head hit the canvas with a jolt that kinda knocked the cobwebs outa my brain.

I shook my head and looked around to locate Biff. He hadn’t gone to no corner but was standing grinning down at me, just back of the referee a ways. The referee was counting, the crowd was clean crazy, and Biff was grinning and waving his gloves at ’em, as much as to say what had he told ’em.

The miners was dancing and capering and mighty near kissing each other in their joy, and the cowboys was white-faced, screaming at me to get up, and reaching for their guns. I believe if I hadn’t of got up, they’d of started slaughtering the miners. But I got up. For the first time I was good and mad at Biff, not because he knocked me down, but because he had such a smug look on his ugly map. I knowed I was the best man, and I was seeing red.

I come up with a roar, and Biff wiped the smirk offa his map quick and met me with a straight left. But I wasn’t to be stopped. I bored into close quarters where I had the advantage, and started ripping away with both hands.

Quickly seeing he couldn’t match me at infighting, Biff grabbed my shoulders and shoved me away by main strength, instantly swinging hard for my head. I ducked and slashed a left hook to his head. He ripped a left to my body and smashed a right to my ear. I staggered him with a left hook to the temple, took a left on the head, and beat him to the punch with a mallet-like right hander to the jaw. I caught him wide open and landed a fraction of a second before he did. That smash had all my beef behind it and Biff dropped like a log.

But he was a glutton for punishment. Snorting and grunting, he got to his all-fours, glassy-eyed but shaking his head, and, as Menly said “nine,” Leary was up. But he was groggy; such a punch as I dropped him with is one you don’t often land. He rushed at me and connected with a swinging left to the ribs that shook me some, but I dropped him again with a blasting left hook to the chin.

This time I seen he’d never beat the count, so I retired to the furtherest corner and grinned at Slim and the other cowboys, who was doing a Indian scalp-dance while the miners was shrieking for Biff to get up.

Menly was counting over him, and, just as he said “seven,” a sudden rattle of shots sounded. Menly stopped short and glared at the mine, half a mile away. All of us looked. A gang of men was riding around the buildings and shooting in them. Menly give a yell and hopped out of the ring.

“Gang up!” he yelled. “It’s López and his men! They’ve come to do all the damage they can while the mine’s unguarded! They’ll burn the office and ruin the machinery if we don’t stop ’em! Come a-runnin’!”

He grabbed a horse and started smoking across the flat, and the crowd followed him, the cowboys on horses, the rest on foot, all with their guns in their hands. Slim jumped down and said to Miss Joan: “You stay here, Miss Joan. You’ll be safe here and we’ll be back and finish this prize fight soon’s we chase them Greasers over the hill.”

Well, I was plumb disgusted to see them mutts all streak off across the flat, leaving me and Biff in the ring, and me with the fight practically won. Biff shook hisself and snorted and come up slugging, but I stepped back and irritably told him to can the comedy.

“What’s up?” said he, glaring around. “Why, where’s Menly? Where’s the crowd? What’s them shots?”

“The crowd’s gone to chase López and his merry men,” I snapped. “Just as I had you out, the fool referee quits countin’.”

“Well, I’d of got up anyhow,” said Biff. “I see now. It is López’s gang, sure enough—”

The cow-punchers and miners had nearly reached the mine by this time, and guns was cracking plenty on both sides. The Mexicans was drawing off, slowly, shooting as they went, but it looked like they was about ready to break and run for it. It seemed like a fool play to me, all the way around.

“Hey, Steve,” said Biff, “whatsa use waitin’ till them mutts gits back? Let’s me and you get our scrap over.”

“Please don’t start fighting till the boys come back,” said Joan, nervously. “There’s something funny about this. I don’t feel just right. Oh—”

She give a kind of scream and turned pale. Outa the ravine behind the ring rode a Mexican. He was young and good-looking but he had a cruel, mocking face; he rode a fine horse and his clothes musta cost six months’ wages. He had on tight pants which the legs flared at the bottoms and was ornamented with silver dollars, fine boots which he wore inside his pants legs, gold-chased spurs, a silk shirt and a jacket with gold lace all over it, and the costliest sombrero I ever seen. Moreover, they was a carbine in a saddle sheath, and he wore a Luger pistol at his hip.

“Murder!” said Biff. “It’s López the Terrible!”

“Greetings, señorita!” said he, with a flash of white teeth under his black mustache, swinging off his sombrero and making a low bow in his saddle. “López keeps his word—have I not said I would come for you? Oho, I am clever. I sent my men to make a disturbance and draw the Americanos away. Now you will come with me to my lair in the hills where no gringo will ever find you!”

Joan was trembling and white-faced, but she was game. “You don’t dare touch an American woman, you murderer!” she said. “My cowboys would hang you on a cactus.”

“I will take the risk,” he purred. “Now, señorita, come—”

“Get up here in the ring, Miss Joan,” I said, leaning down to give her a hand. “That’s it—right up with me and Biff. We won’t let no harm come to you. Now, Mr. López, if that’s your name, I’m givin’ you your sailin’ orders—weigh anchor and steer for some other port before I bend one on your jaw.”

“I echoes them sentiments,” said Biff, spitting on his gloves and hitching at his trunks.

López’s white teeth flashed in a snarl like a wolf’s. His Luger snaked into his hand.

“So,” he purred, “these men of beef, these bruisers dare defy López!” He reined up alongside the ring and, placing one hand on a post, vaulted over the ropes, his pistol still menacing me and Biff. Joan, at my motion, hadst retreated back to the other side of the ring. López began to walk towards us, like a cat stalking a mouse.

“The girl I take,” he said, soft and deadly. “Let neither of you move if you wish to live.”

“Well, Biff,” I said, tensing myself, “we’ll rush him from both sides. He’ll get one of us but the other’n’ll git him.”

“Oh, don’t!” cried Joan. “He’ll kill you. I’d rather—”

“Let’s go!” roared Biff, and we plunged at López simultaneous.

But that Mex was quicker than a cat; he whipped from one to the other of us and his gun cracked twice. I heard Biff swear and saw him stumble, and something that burned hit me in the left shoulder.

Before López couldst fire again, I was on him, and I ripped the gun outa his hand and belted him over the head with it just as Biff smashed him on the jaw. López the Terrible stretched out limp as a sail-rope, and he didn’t even twitch.

“Oh, you’re shot, both of you!” wailed Joan, running across the ring toward us. “Oh, I feel like a murderer! I shouldn’t have let you do it. Let me see your wounds.”

Biff’s left arm was hanging limp and blood was oozing from a neat round hole above the elbow. My own left was getting so stiff I couldn’t lift it, and blood was trickling down my chest.

“Heck, Miss Joan,” I said, “don’t worry ’bout us. Lucky for us López was usin’ them steel-jacket bullets that make a clean wound and don’t tear. But I hate about me and Biff not gettin’ to finish our scrap—”

“Hey, Steve,” said Biff hurriedly, “the boys has chased off the bandits and heered the shots, and here they come across the flat on the run! Let’s us finish our go before they git here. They won’t let us go on if we don’t do it now. And we may never git another chance. You’ll go off to your ship tomorrer and we may never see each other again. Come on. I’m shot through the left arm and you got a bullet through your left shoulder, but our rights is okay. Let’s toss this mutt outa the ring and give each other one more good slam!”

“Fair enough, Biff,” said I. “Come on, before we gets weak from losin’ blood.”

Joan started crying and wringing her hands.

“Oh, please, please, boys, don’t fight each other any more! You’ll bleed to death. Let me bandage your wounds—”

“Shucks, Miss Joan,” said I, patting her slim shoulder soothingly, “me and Biff ain’t hurt, but we gotta settle our argument. Don’t you fret your purty head none.”

We unceremoniously tossed the limp and senseless bandit outa the ring and we squared off, with our rights cocked and our lefts hanging at our sides, just as the foremost of the cow-punchers came riding up.

We heard the astounded yells of Menly, Slim and the rest, and Miss Joan begging ’em to stop us, and then we braced our legs, took a deep breath and let go.

We both crashed our rights at exactly the same instant, and we both landed—square on the button. And we both went down. I was up almost in a instant, groggy and dizzy and only partly aware of what was going on, but Biff didn’t twitch.

The next minute Menly and Steve and Tex and all the rest was swarming over the ropes, yelling and hollering and demanding to know what it was all about, and Miss Joan was crying and trying to tell ’em and tend to Biff’s wound.

“Hey!” yelled Yuma, outside the ring. “That was López I seen ride up to the ring a while ago—here he is with a three-inch gash in his scalp and a fractured jawbone!”

“Ain’t that what Miss Joan’s been tellin’ you?” I snapped. “Help her with Biff before he bleeds to death—naw, tend to him first—I’m all right.”

Biff come to about that time and nearly knocked Menly’s head off before he knowed where he was, and later, while they was bandaging us, Biff said: “I wanta tell you, Steve, I still don’t consider you has licked me, and I’m figgerin’ on lookin’ you up soon’s as my arm’s healed up.”

“Okay with me, Snoots,” I grinned. “I gets more enjoyment outa fightin’ you than anybody. Reckon there’s fightin’ Texas feud betwixt me and you.”

“Well, Steve,” said Slim, “we said we’d make it worth your while—what’ll it be?”

“I wouldn’t accept no pay for fightin’ a old friend like Biff,” said I. “All I wantcha to do is get me back in port in time to sail with the Sea Girl. And, Miss Joan, I hope you don’t feel scared of me no more.”

Her answer made both me and Biff blush like school-kids. She kissed us.