Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

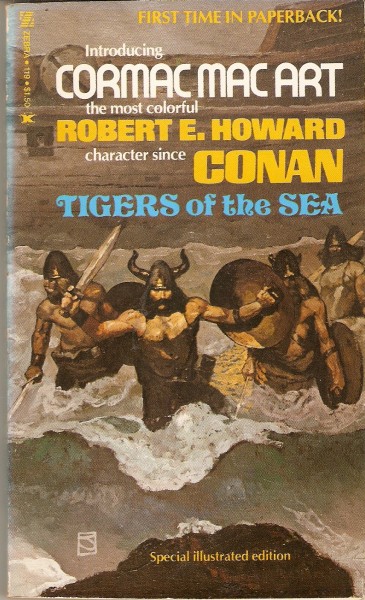

Published in Tigers of the Sea, 1974.

“Easy all,” grunted Wulfhere Hausakliufr. “I see the glimmer of a stone building through the trees. . . . Thor’s blood, Cormac! are you leading us into a trap?”

The tall Gael shook his head, a frown darkening his sinister, scarred face.

“I never heard of a castle in these parts; the British tribes hereabouts don’t build in stone. It may be an old Roman ruin—”

Wulfhere hesitated, glancing back at the compact lines of bearded, horn-helmeted warriors. “Maybe we’d best send out a scout.”

Cormac Mac Art laughed jeeringly. “Alaric led his Goths through the Forum over eighty years ago, yet you barbarians still start at the name of Rome. Fear not; there are no legions in Britain. I think this is a Druidic temple. We have nothing to fear from them—more especially as we are moving against their hereditary enemies.”

“And Cerdic’s brood will howl like wolves when we strike them from the west instead of the south or east,” said the Skull-splitter with a grin. “It was a crafty idea of yours, Cormac, to hide our dragon-ship on the west coast and march straight through British country to fall on the Saxons. But it’s mad, too.”

“There’s method in my madness,” responded the Gael. “I know that there are few warriors hereabouts; most of the chiefs are gathering about Arthur Pendragon for a great concerted drive. Pendragon—ha! He’s no more Uther Pendragon’s son than you are. Uther was a black-bearded madman—more Roman than Briton and more Gaul than Roman. Arthur is as fair as Eric there. And he’s pure Celt—a waif from one of the wild western tribes that never bowed to Rome. It was Lancelot who put it into his head to make himself king—else he had still been no more than a wild chief raiding the borders.”

“Has he become smooth and polished like the Romans were?”

“Arthur? Ha! One of your Danes might seem a gentlewoman beside him. He’s a shock-headed savage with a love for battle.” Cormac grinned ferociously and touched his scars. “By the blood of the gods, he has a hungry sword! It’s little gain we reivers from Erin have gotten on his coasts!”

“Would I could cross steel with him,” grunted Wulfhere, thumbing the flaring edge of his great axe. “What of Lancelot?”

“A renegade Gallo-Roman who has made an art of throat-cutting. He varies reading Petronius with plotting and intriguing. Gawaine is a pure-blooded Briton like Arthur, but he has Romanish leanings. You’d laugh to see him aping Lancelot—but he fights like a blood-hungry devil. Without these two, Arthur would have been no more than a bandit chief. He can neither read nor write.”

“What of that?” rumbled the Dane. “Neither can I. . . . Look—there’s the temple.

They had entered the tall grove in whose shadows crouched the broad, squat building that seemed to leer out at them from behind a screening row of columns.

“This can be no temple of the Britons,” growled Wulfhere. “I thought they were mostly of a sickly new sect called Christians.”

“The Roman-British mongrels are,” said Cormac. “The pure Celts hold to the old gods, as do we of Erin. By the blood of the gods, we Gaels will never turn Christian while one Druid lives!”

“What do these Christians?” asked Wulfhere curiously.

“They eat babies during their ceremonies, it is said.”

“But ’tis also said the Druids burn men in cages of green wood.”

“A lie spread by Caesar and believed by fools!” rasped Cormac impatiently. “I laud not the Druids especially, but wisdom of the elements and ages is not denied to them. These Christians teach meekness and the bowing of the neck to the blow.”

“What say you?” The great Viking was sincerely amazed. “Is it truly their creed to take blows like slaves?”

“Aye—to return good for evil and to forgive their oppressors.”

The giant meditated on this statement for a moment. “That is not a creed, but cowardice,” he decided finally. “These Christians be all madmen. Cormac, if you recognize one of that breed, point him out and I will try his faith.” He lifted his axe meaningfully. “For look you,” he said, “that is an insidious and dangerous teaching which may spread like rust on the wheat and undermine the manhood of men if it be not stamped out like a young serpent under heel.”

“Let me but see one of these madmen,” said Cormac grimly, “and I will begin the stamping. But let us see to this temple. Wait here—I’m of the same belief as these Britons, if I am of a different race. These Druids will bless our raid against the Saxons. Much is mummery, but their friendship at least is desirable.”

The Gael strode between the columns and vanished. The Hausakliufr leaned on his axe; it seemed to him that from within came a faint rattle—like the hoofs of a goat on a marble floor.

“This is an evil place,” muttered Osric Jarl’s-bane. “I thought I saw a strange face peering about the top of the column a moment agone.”

“It was a fungus vine grown and twisted about,” Black Hrothgar contradicted him. “See how the fungus springs up all about the temple—how it twists and writhes like souls in torment—how human-like is its appearance—”

“You are both mad,” broke in Hakon Snorri’s son. “It was a goat you saw—I saw the horns that grew upon its head—”

“Thor’s blood,” snarled Wulfhere, “be silent—listen!”

Within the temple had sounded the echo of a sharp, incredulous cry; a sudden, demonic rapping as of fantastic hoofs on marble flags; the rasp of a sword from its scabbard, and a heavy blow. Wulfhere gripped his axe and took the first step of a headlong charge for the portals. Then from between the columns, in silent haste, came Cormac Mac Art. Wulfhere’s eyes widened and a slow horror crept over him, for never till this moment had he seen the steel nerves of the lean, Gael shaken—yet now the color was gone from Cormac’s face and his eyes stared like those of a man who has looked into dark, nameless gulfs. His blade dripped red.

“What in the name of Thor—?” growled Wulfhere, peering fearfully into the shadow-haunted shrine.

Cormac wiped away beads of cold sweat and moistened his lips.

“By the blood of the gods,” he said, “we have stumbled upon an abomination—or else I am mad! From the inner gloom it came bounding and capering—suddenly—and it almost had me in its grasp before I had sense enough to draw and strike. It leaped and capered like a goat, but ran upright—and in the dim light it was not unlike a man.”

“You are mad,” said Wulfhere uneasily; his mythology did not include satyrs.

“Well,” snapped Cormac, “the thing lies upon the flags within; follow me, and I will prove to you whether I am mad.”

He turned and strode through the columns, and Wulfhere followed, axe ready, his Vikings trailing behind him in close formation and going warily. They passed between the columns, which were plain and without ornamentation of any kind, and entered the temple. Here they found themselves within a broad hall flanked with squat pillars of black stone—and these indeed were carved. A squat figure squatted on the top of each, as upon a pedestal, but in the dim light it was impossible to make out what sort of beings these figures represented, though there was an abhorrent hint of abnormality about each shape.

“Well,” said Wulfhere impatiently, “where is your monster?”

“There he fell,” said Cormac, pointing with his sword, “and—by the black gods!” The flags lay bare.

“Moon-mist and madness,” said Wulfhere, shaking his head. “Celtic superstition. You see ghosts, Cormac!”

“Yes?” snapped the badgered Gael. “Who saw a troll on the beacon of Helgoland and roused the whole camp with shouts and bellowings? Who kept the band under arms all night and kept men feeding the fires till they nearly dropped, to scare away the things of darkness?”

Wulfhere growled uncomfortably and glared at his warriors as if to challenge anyone to laugh.

“Look,” said Cormac, bending closer. On the tiling was a wide smear of blood, freshly spilt. Wulfhere took a single glance and then straightened quickly, glaring into the shadows. His men bunched closer, facing outward, beards a-bristle. A tense silence reigned.

“Follow me,” said Cormac in a low tone, and they pressed close at his heels as he walked warily down the broad corridor. Apparently no entrance opened between the brooding, evil pillars. Ahead of them the shadows paled and they came forth into a broad circular chamber with a domed ceiling. Around this chamber were more pillars, regularly spaced, and in the light that flowed somehow through the dome the warriors saw the nature of those pillars and the shapes that crowned them. Cormac swore between his teeth and Wulfhere spat. The figures were human, and not even the most perverse and degenerate geniuses of decadent Greece and later Rome could have conceived such obscenities or breathed into the tortured stone such foul life.

Cormac scowled. Here and there in the sculpturing the unknown artists had struck a cord of unrealness—a hint of abnormality beyond any human deformity. These touches roused in him a vague uneasiness, a crawling, shuddersome half-fear that lurked white-maned and grisly at the back of his mind. . . .

The thought that he had briefly entertained, that he had seen and slain an hallucination, vanished.

Besides the doorway through which they had entered the chamber, four other portals showed—narrow, arched doorways, apparently without doors. There was no altar visible. Cormac strode to the center of the dome and looked up; its shadowy hollow arched above him, sullen and brooding. His gaze sought the floor on which he stood and he noted the pattern—of tiling rather than flags, and laid in a design the lines of which converged to the center of the floor. The focus of that design was a single, broad, octagonal slab on which he was standing. . . .

Then, even as he realized that he was standing on that slab, it fell away silently from under his feet and he felt himself plunging into an abyss beneath.

Only the Gael’s superhuman quickness saved him. Thorfinn Jarl’s-bane was standing nearest him and, as the Gael dropped, he shot out a long arm and clutched at the Dane’s sword-belt. The desperate fingers missed, but closed on the scabbard—and, as Thorfinn instinctively braced his legs, Cormac’s fall was checked and he swung suspended, life hanging on the grip of his single hand and the strength of the scabbard loops. In an instant Thorfinn had seized his wrist, and Wulfhere, leaping forward with a roar of alarm, added the grasp of his huge hand. Between them they heaved the Gael up out of the gaping blackness, Cormac aiding them with a twist and a lift of his rangy form that swung his legs up over the brink.

“Thor’s blood!” ejaculated Wulfhere, more shaken by the experience than was Cormac. “It was touch and go then. . . . By Thor, you still hold your sword!”

“When I drop it, life will no longer be in me,” said Cormac. “I mean to carry it into hell with me. But let me look into this gulf that opened beneath me so suddenly.”

“More traps may fall,” said Wulfhere uneasily.

“I see the sides of the well,” said Cormac, leaning and peering, “but my gaze is swiftly swallowed in darkness. . . . What a foul stench drifts up from below!”

“Come away,” said Wulfhere hurriedly. “That stench was never born on earth. This well must lead into some Roman Hades—or mayhap the cavern where the serpent drips venom on Loki.”

Cormac paid no heed. “I see the trap now,” said he. “That slab was balanced on a sort of pivot, and here is the catch that supported it. How it was worked I can’t say, but this catch was released and the slab fell, held on one side by the pivot. . . .”

His voice trailed away. Then he said, suddenly: “Blood—blood on the edge of the pit!”

“The thing you slashed,” grunted Wulfhere. “It has crawled into the gulf.”

“Not unless dead things crawl,” growled Cormac. “I killed it, I tell you. It was carried here and thrown in. Listen!”

The warriors bent close; from somewhere far down—an incredible distance, it seemed—there came a sound: a nasty, squashy, wallowing sound, mingled with noises indescribable and unrecognizable.

With one accord the warriors drew away from the well and, exchanging silent glances, gripped their weapons.

“This stone won’t burn,” growled Wulfhere, voicing a common thought. “There’s no loot here and nothing human. Let’s be gone.”

“Wait!” The keen-eared Gael threw up his head like a hunting hound. He frowned, and drew nearer to one of the arched openings.

“A human groan,” he whispered. “Did you not hear it?”

Wulfhere bent his head, cupping palm to ear. “Aye—down that corridor.”

“Follow me,” snapped the Gael. “Stay close together. Wulfhere, grip my belt; Hrothgar, hold Wulfhere’s, and Hakon, Hrothgar’s. There may be more pits. The rest of you dress your shields, and each man keep close touch with the next.”

So in a compact mass they squeezed through the narrow portal and found the corridor much wider than they had thought for. There it was darker, but further down the corridor they saw what appeared to be a patch of light.

They hastened to it and halted. Here indeed it was lighter, so that the unspeakable carven obscenities thronging the wall were cast into plain sight. This light came in from above, where the ceiling had been pierced with several openings—and, chained to the wall among the foul carvings, hung a naked form. It was a man who sagged on the chains that held him half erect. At first Cormac thought him dead—and, staring at the grisly mutilations that had been wrought upon him, decided it was better so. Then the head lifted slightly, and a low, moan sighed through the pulped lips.

“By Thor,” swore Wulfhere in amazement, “he lives!”

“Water, in God’s name,” whispered the man on the wall.

Cormac, taking a well-filled flask from Hakon Snorri’s son, held it to the creature’s lips. The man drank in great, gasping gulps, then lifted his head with a mighty effort. The Gael looked into deep eyes that were strangely calm.

“God’s benison on you, my lords,” came the voice, faint and rattling, yet somehow suggesting that it had once been strong and resonant. “Has the long torment ended and am I in Paradise at last?”

Wulfhere and Cormac glanced at each other curiously. Paradise! Strange indeed, thought Cormac, would such red-handed reivers as we look in the temple of the humble ones!

“Nay, it is not Paradise,” muttered the man deliriously, “for I am still galled by these heavy chains.”

Wulfhere bent and examined the chains that held him. Then with a grunt he raised his axe and, shortening his hold upon the haft, smote a short, powerful blow. The links parted beneath the keen edge and the man slumped forward into Cormac’s arms, free of the wall but with the heavy bands still upon wrists and ankles; these, Cormac saw, sank deeply into the flesh which the rough and rusty metal envenomed.

“I think you have not long to live, good sir,” said Cormac. “Tell us how you are named and where your village is, so it may be we might tell your people of your passing.”

“My name is Fabricus, my lord,” said the victim, speaking with difficulty. “My town is any which still holds the Saxon at bay.”

“You are a Christian, by your words,” said Cormac, and Wulfhere gazed curiously.

“I am but a humble priest of God, noble sir,” whispered the other. “But you must not linger. Leave me here and go quickly lest evil befall you.”

“By the blood of Odin,” snorted Wulfhere, “I quit not this place until I learn who it is that treats living beings so foully!”

“Evil blacker than the dark side of the moon,” muttered Fabricus. “Before it, the differences of man fade so that you seem to me like a brother of the blood and of the milk, Saxon.”

“I am no Saxon, friend,” rumbled the Dane.

“No matter—all men in the rightful form of man are brothers. Such is the word of the Lord—which I had not fully comprehended until I came to this place of abominations!”

“Thor!” muttered Wulfhere. “Is this no Druidic temple?”

“Nay,” answered the dying man, “not a temple where men, even in heathenness, deify the cleaner forms of Nature. Ah, God—they hem me close! Avaunt, foul demons of the Outer Dark—creeping, creeping—crawling shapes of red chaos and howling madness—slithering, lurking blasphemies that hid like reptiles in the ships of Rome—ghastly beings spawned in the ooze of the Orient, transplanted to cleaner lands, rooting themselves deep in good British soil—oaks older than the Druids, that feed on monstrous things beneath the bloating moon—”

The mutter of delirium faltered and faded, and Cormac shook the priest lightly. The dying man roused as a man waking slowly from deep sleep.

“Go, I beg of you,” he whispered. “They have done their worst to me. But you—they will lap with evil spells—they will break your body as they have shattered mine—they will seek to break your souls as they had broken mine but for my everlasting faith in our good Lord God. He will come, the monster, the high priest of infamy, with his legions of the damned—listen!” The dying head lifted. “Even now he comes! Now may God protect us all!”

Cormac snarled like a wolf and the great Viking wheeled about, rumbling defiance like a lion at bay. Aye, something was coming down one of the smaller corridors which opened into that wider one. There was a myriad rattling of hoofs on the tiling—“Close the ranks!” snarled Wulfhere. “Make the shield-wall, wolves, and die with your axes red!”

The Vikings quickly formed into a half-moon of steel, surrounding the dying priest and facing outward, just as a hideous horde burst from the dark opening into the comparative light. In a flood of black madness and red horror their assailants swept upon them. Most of them were goat-like creatures, that ran upright and had human hands and faces frightfully partaking of both goat and human. But among their ranks were shapes even more fearful. And behind them all, luminous with an evil light in the darkness of the winding corridor from which the horde emerged, Cormac saw an unholy countenance, human, yet more and less than human. Then on that solid iron wall the noisome horde broke.

The creatures were unarmed, but they were horned, fanged and taloned. They fought as beasts fight, but with less of the beast’s cunning and skill. And the Vikings, eyes blazing and beards a-bristle with the battle-lust, swung their axes in mighty strokes of death: Girding horn, slashing talon and gnashing fang found flesh and drew blood in streams, but protected by their helmets, mail and over-lapping shields, the Danes suffered comparatively little while their whistling axes and stabbing spears took ghastly toll among their unprotected assailants.

“Thor and the blood of Thor,” cursed Wulfhere, cleaving a goat-thing clear through the body with a single stroke of his red axe, “mayhap ye find it a harder thing to slay armed men than to torture a naked priest, spawn of Helheim!”

Before that rain of hacking steel the hell-horde broke, but behind them the half-seen man among the shadows drove them back to the onslaught with strange chanting words, unintelligible to the humans who strove against his vassals. So his creatures turned again to the fray with desperate fury, until the dead things lay piled high about the feet of their slayers, and the few survivors broke and fled down the corridor. The Vikings would have scattered in pursuit but Wulfhere’s bellow halted them. But as the horde broke, Cormac bounded across the sprawling corpses and raced down the winding corridor in pursuit of one who fled before him. His quarry turned up another corridor and finally raced out into the domed main chamber, and there he turned at bay—a tall man with inhuman eyes and a strange, dark face, naked but for fantastic ornaments.

With his strange short, curved sword he sought to parry the Gael’s headlong attack—but Cormac in his red fury drove his foe before him like a straw before the wind. Whatever else this high priest might be, he was mortal, for he winced and cursed in a weird tongue as Cormac’s long lean blade broke through his guard again and again and brought blood from head, chest and arm. Back Cormac drove him, inexorably, until he wavered on the very brink of the open pit—and there, as the Gael’s point girded into his breast, he reeled and fell backward with a wild cry. . . .

For a long moment that cry rang up ever more faintly from untold depths—then ceased abruptly. And far below rose sounds as of a grisly feast. Cormac smiled fiercely. For the moment, not even the inhuman sounds from the gulf could shake him in his grim fury; he was the Avenger, and he had just sent a tormentor of one of his own kind to the maw of a devouring god of judgement. . . .

He turned and strode back down the hall to join Wulfhere and his men. A few goat-things passed before him in the dim corridors, but fled bleating before his grim advance. Cormac paid them no heed, and presently rejoined Wulfhere and the dying priest.

“You have slain the Dark Druid,” whispered Fabricus. “Aye, his blood stains your blade—I see it glowing even through your sheath, though others cannot, and so I know I am free at last to speak. Before the Romans, before the true Celtic Druids, before the Gaels and the Picts, even, was the Dark Druid—the Teacher of Man. So he styled himself, for he was the last of the Serpent-Men, the last of that race that preceded humanity in dominion over the world. His was the hand that gave to Eve the apple, and set Adam’s foot upon the accursed path of awakening. King Kull of Atlantis slew the last of His brethren with the edge of the sword in desperate conflict, but He alone survived to ape the form of man and hand down the Satanic lore of olden times. I see many things now—things that life hid but which the opening doors of death reveal! Before Man were the Serpent-men, and before them were the Old Ones of the Star-shaped heads, who created mankind and, later, the abominable goat-spawn when they realized Man would not serve their purpose. This temple is the last Outpost of their accursed civilization to remain above ground—and beneath it ravages the last Shoggoth to remain near the surface of this world. The goat-spawn roam the hills only at night, fearful now of man, and the Old Ones and the Shoggoths hide deep beneath the earth till that day when God mayhap shall call them forth to be his scourge, at Armageddon. . . .”

The old man coughed and gasped, and Cormac’s skin prickled strangely. Too many of the things Fabricus said seemed to stir strange memories in his Gaelic racial soul.

“Rest easy, old man,” he said. “This temple—this Outpost, as you call it, shall not remain standing.”

“Aye,” grunted Wulfhere, strangely moved. “Every stone in this place shall be cast into the pit that lies beneath!”

Cormac, too, felt an unaccustomed sadness—why he knew not, for often had he seen death before. “Christian or no, your’s is a brave soul, old man. You shall be avenged. . . .”

“Nay!” Fabricus held up a trembling, bloodless hand; his face seemed to shine with a mystic intensity. “I die, and vengeance means naught to my departing soul. I came to this evil place bearing the cross and speaking the cleansing words of our Lord, willing to die if only this world might be purged of that Dark One who has so foully slain so many and who plotted the Second Downfall of us all. And God has answered my prayers, for He has sent you here and you have slain the Serpent; now the Serpent’s goat-minions can but flee to the wooded hills, and the Shoggoth return to the dark bowels of Hell whence it came.” Fabricus gripped Cormac’s right hand with his left, Wulfhere’s with his right; then he said: “Gael—Norse—fellow humans you be, though of different races, different beliefs. . . . Look now!” His countenance seemed to shine with a strange light as he feebly raised himself on one elbow. “It is as our Lord told me—all difference between us pale before the menace of the Dark Powers—aye, we be all brothers. . . .”

Then the mystic, far-seeing eyes of Fabricus rolled upward and closed—in death. Cormac stood in grim silence, gripping his naked sword, then drew breath deeply and relaxed.

“What meant the man?” he grunted at last.

Wulfhere shook his shaggy mane. “I know not. He was mad, and his madness led him to his doom. Yet he had courage, for did he not go forth fearless, even as goes the berserker into battle, careless of death? He was a brave man—but this temple is an evil place that were better quitted. . . .”

“Aye—and the sooner the better!”

Cormac sheathed his sword with a clang; again he breathed deeply.

“On to Wessex,” he growled. “We’ll clean our steel in good Saxon blood.”