Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

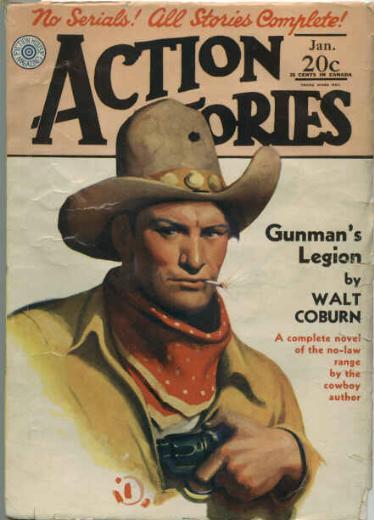

Published in Action Stories, Vol. 10, No. 5 (January 1931).

The first thing that happened in Cape Town, my white bulldog Mike bit a policeman and I had to come across with a fine of ten dollars, to pay for the cop’s britches. That left me busted, not more’n an hour after the Sea Girl docked.

The next thing who should I come on to but Shifty Kerren, manager of Kid Delrano, and the crookedest leather-pilot which ever swiped the gate receipts. I favored this worthy with a hearty scowl, but he had the everlasting nerve to smile welcomingly and hold out the glad hand.

“Well, well! If it ain’t Steve Costigan! Howdy, Steve!” said the infamous hypocrite. “Glad to see you. Boy, you’re lookin’ fine! Got good old Mike with you, I see. Nice dawg.”

He leaned over to pat him.

“Grrrrrr!” said good old Mike, fixing for to chaw his hand. I pushed Mike away with my foot and said to Shifty, I said: “A big nerve you got, tryin’ to fraternize with me, after the way you squawked and whooped the last time I seen you, and called me a dub and all.”

“Now, now, Steve!” said Shifty. “Don’t be foolish and go holdin’ no grudge. It’s all in the way of business, you know. I allus did like you, Steve.”

“Gaaahh!” I responded ungraciously. I didn’t have no wish to hobnob none with him, though I figgered I was safe enough, being as I was broke anyway.

I’ve fought that palooka of his twice. The first time he outpointed me in a ten-round bout in Seattle, but didn’t hurt me none, him being a classy boxer but kinda shy on the punch.

Next time we met in a Frisco ring, scheduled for fifteen frames. Kid Delrano give me a proper shellacking for ten rounds, then punched hisself out in a vain attempt to stop me, and blowed up. I had him on the canvas in the eleventh and again in the twelfth and with the fourteenth a minute to go, I rammed a right to the wrist in his solar plexus that put him down again. He had sense enough left to grab his groin and writhe around.

And Shifty jumped up and down and yelled: “Foul!” so loud the referee got scared and rattled and disqualified me. I swear it wasn’t no foul. I landed solid above the belt line. But I officially lost the decision and it kinda rankled.

So now I glowered at Shifty and said: “What you want of me?”

“Steve,” said Shifty, putting his hand on my shoulder in the old comradely way his kind has when they figger on putting the skids under you, “I know you got a heart of gold! You wouldn’t leave no feller countryman in the toils, would you? Naw! Of course you wouldn’t! Not good old Steve. Well, listen, me and the Kid is in a jam. We’re broke—and the Kid’s in jail.

“We got a raw deal when we come here. These Britishers went and disqualified the Kid for merely bitin’ one of their ham-and-eggers. The Kid didn’t mean nothin’ by it. He’s just kinda excitable thataway.”

“Yeah, I know,” I growled. “I got a scar on my neck now from the rat’s fangs. He got excitable with me, too.”

“Well,” said Shifty hurriedly, “they won’t let us fight here now, and we figgered on movin’ upcountry into Johannesburg. Young Hilan is tourin’ South Africa and we can get a fight with him there. His manager—er, I mean a promoter there—sent us tickets, but the Kid’s in jail. They won’t let him out unless we pay a fine of six pounds. That’s thirty dollars, you know. And we’re broke.

“Steve,” went on Shifty, waxing eloquent, “I appeals to your national pride! Here’s the Kid, a American like yourself, pent up in durance vile, and for no more reason than for just takin’ up for his own country—”

“Huh!” I perked up my ears. “How’s that?”

“Well, he blows into a pub where three British sailors makes slanderous remarks about American ships and seamen. Well, you know the Kid—just a big, free-hearted, impulsive boy, and terrible proud of his country, like a man should be. He ain’t no sailor, of course, but them remarks was a insult to his countrymen and he wades in. He gives them limeys a proper drubbin’ but here comes a host of cops which hauls him before the local magistrate which hands him a fine we can’t pay.

“Think, Steve!” orated Shifty. “There’s the Kid, with thousands of admirin’ fans back in the States waitin’ and watchin’ for his triumphal return to the land of the free and the home of the brave. And here’s him, wastin’ his young manhood in a stone dungeon, bein’ fed on bread and water and maybe beat up by the jailers, merely for standin’ up for his own flag and nation. For defendin’ the honor of American sailors, mind you, of which you is one. I’m askin’ you, Steve, be you goin’ to stand by and let a feller countryman languish in the ’thrallin’ chains of British tyranny?”

“Not by a long ways!” said I, all my patriotism roused and roaring. “Let bygones be bygones!” I said.

It’s a kind of unwritten law among sailors ashore that they should stand by their own kind. A kind of waterfront law, I might say.

“I ain’t fought limeys all over the world to let an American be given the works by ’em now,” I said. “I ain’t got a cent, Shifty, but I’m goin’ to get some dough.

“Meet me at the American Seamen’s Bar in three hours. I’ll have the dough for the Kid’s fine or I’ll know the reason why.

“You understand, I ain’t doin’ this altogether for the Kid. I still intends to punch his block off some day. But he’s an American and so am I, and I reckon I ain’t so small that I’ll let personal grudges stand in the way of helpin’ a countryman in a foreign land.”

“Spoken like a man, Steve!” applauded Shifty, and me and Mike hustled away.

A short, fast walk brung us to a building on the waterfront which had a sign saying: “The South African Sports Arena.” This was all lit up and yells was coming forth by which I knowed fights was going on inside.

The ticket shark told me the main bout had just begun. I told him to send me the promoter, “Bulawayo” Hurley, which I’d fought for of yore, and he told me that Bulawayo was in his office, which was a small room next to the ticket booth. So I went in and seen Bulawayo talking to a tall, lean gent the sight of which made my neck hair bristle.

“Hey, Bulawayo,” said I, ignoring the other mutt and coming direct to the point, “I want a fight. I want to fight tonight—right now. Have you got anybody you’ll throw in with me, or if not willya let me get up in your ring and challenge the house for a purse to be made up by the crowd?”

“By a strange coincidence,” said Bulawayo, pulling his big mustache, “here’s Bucko Brent askin’ me the same blightin’ thing.”

Me and Bucko gazed at each other with hearty disapproval. I’d had dealings with this thug before. In fact, I built a good part of my reputation as a bucko-breaker on his lanky frame. A bucko, as you likely know, is a hard-case mate, who punches his crew around. Brent was all that and more. Ashore he was a prize-fighter, same as me.

Quite a few years ago I was fool enough to ship as a.b. on the Elinor, which he was mate of then. He’s an Australian and the Elinor was an Australian ship. Australian ships is usually good crafts to sign up with, but this here Elinor was a exception. Her cap’n was a relic of the old hellship days, and her mates was natural-born bullies. Brent especially, as his nickname of “Bucko” shows. But I was broke and wanted to get to Makassar to meet the Sea Girl there, so I shipped aboard the Elinor at Bristol.

Brent started ragging me before we weighed anchor.

Well, I stood his hazing for a few days and then I got plenty and we went together. We fought the biggest part of one watch, all over the ship from the mizzen cross trees to the bowsprit. Yet it wasn’t what I wouldst call a square test of manhood because marlin spikes and belaying pins was used free and generous on both sides and the entire tactics smacked of rough house.

In fact, I finally won the fight by throwing him bodily offa the poop. He hit on his head on the after deck and wasn’t much good the rest of the cruise, what with a broken arm, three cracked ribs and a busted nose. And the cap’n wouldn’t even order me to scrape the anchor chain less’n he had a gun in each hand, though I wasn’t figgering on socking the old rum-soaked antique.

Well, in Bulawayo’s office me and Bucko now set and glared at each other, and what we was thinking probably wasn’t printable.

“Tell you what, boys,” said Bulawayo, “I’ll let you fight ten rounds as soon as the main event’s over with. I’ll put up five pounds and the winner gets it all.”

“Good enough for me,” growled Bucko.

“Make it six pounds and it’s a go,” said I.

“Done!” said Bulawayo, who realized what a break he was getting, having me fight for him for thirty dollars.

Bucko give me a nasty grin.

“At last, you blasted Yank,” said he, “I got you where I want you. They’ll be no poop deck for me to slip and fall off this time. And you can’t hit me with no hand spike.”

“A fine bird you are, talkin’ about hand spikes,” I snarled, “after tryin’ to tear off a section of the main-rail to sock me with.”

“Belay!” hastily interrupted Bulawayo. “Preserve your ire for the ring.”

“Is they any Sea Girl men out front?” I asked. “I want a handler to see that none of this thug’s henchmen don’t dope my water bottle.”

“Strangely enough, Steve,” said Bulawayo, “I ain’t seen a Sea Girl bloke tonight. But I’ll get a handler for you.”

Well, the main event went the limit. It seemed like it never would get over with and I cussed to myself at the idea of a couple of dubs like them was delaying the performance of a man like me. At last, however, the referee called it a draw and kicked the both of them outa the ring.

Bulawayo hopped through the ropes and stopped the folks who’d started to go, by telling them he was offering a free and added attraction—Sailor Costigan and Bucko Brent in a impromptu grudge bout. This was good business for Bulawayo. It tickled the crowd who’d seen both of us fight, though not ag’in each other, of course. They cheered Bulawayo to the echo and settled back with whoops of delight.

Bulawayo was right—not a Sea Girl man in the house. All drunk or in jail or something, I suppose. They was quite a number of thugs there from the Nagpur—Brent’s present ship—and they all rose as one and gimme the razz. Sailors is funny. I know that Brent hazed the liver outa them, yet they was rooting for him like he was their brother or something.

I made no reply to their jeers, maintaining a dignified and aloof silence only except to tell them that I was going to tear their pet mate apart and strew the fragments to the four winds, and also to warn them not to try no monkey-shines behind my back, otherwise I wouldst let Mike chaw their legs off. They greeted my brief observations with loud, raucous bellerings, but looked at Mike with considerable awe.

The referee was an Englishman whose name I forget, but he hadn’t been outa the old country very long, and had evidently got his experience in the polite athletic clubs of London. He says: “Now understand this, you blighters, w’en H’I says break, H’I wants no bally nonsense. Remember as long as H’I’m in ’ere, this is a blinkin’ gentleman’s gyme.”

But he got in the ring with us, American style.

Bucko is one of these long, rangy, lean fellers, kinda pale and rawboned. He’s got a thin hatchet face and mean light eyes. He’s a bad actor and that ain’t no lie. I’m six feet and weigh one ninety. He’s a inch and three-quarters taller’n me, and he weighed then, maybe, a pound less’n me.

Bucko come out stabbing with his left, but I was watching his right. I knowed he packed his t.n.t. there and he was pretty classy with it.

In about ten seconds he nailed me with that right and I seen stars. I went back on my heels and he was on top of me in a second, hammering hard with both hands, wild for a knockout. He battered me back across the ring. I wasn’t really hurt, though he thought I was. Friends of his which had seen me perform before was yelling for him to be careful, but he paid no heed.

With my back against the ropes I failed to block his right to the body and he rocked my head back with a hard left hook.

“You’re not so tough, you lousy mick—” he sneered, shooting for my jaw. Wham! I ripped a slungshot right uppercut up inside his left and tagged him flush on the button. It lifted him clean offa his feet and dropped him on the seat of his trunks, where he set looking up at the referee with a goofy and glassy-eyed stare, whilst his friends jumped up and down and cussed and howled: “We told you to be careful with that gorilla, you conceited jassack!”

But Bucko was tough. He kind of assembled hisself and was up at the count of “Nine,” groggy but full of fight and plenty mad. I come in wide open to finish him, and run square into that deadly right. I thought for a instant the top of my head was tore off, but rallied and shook Bucko from stem to stern with a left hook under the heart. He tin-canned in a hurry, covering his retreat with his sharp-shooting left. The gong found me vainly follering him around the ring.

The next round started with the fans which was betting on Bucko urging him to keep away from me and box me. Them that had put money on me was yelling for him to take a chance and mix it with me.

But he was plenty cagey. He kept his right bent across his midriff, his chin tucked behind his shoulder and his left out to fend me off. He landed repeatedly with that left and brung a trickle of blood from my lips, but I paid no attention. The left ain’t made that can keep me off forever. Toward the end of the round he suddenly let go with that right again and I took it square in the face to get in a right to his ribs.

Blood spattered when his right landed. The crowd leaped up, yelling, not noticing the short-armed smash I ripped in under his heart. But he noticed it, you bet, and broke ground in a hurry, gasping, much to the astonishment of the crowd, which yelled for him to go in and finish the blawsted Yankee.

Crowds don’t see much of what’s going on in the ring before their eyes, after all. They see the wild swings and haymakers but they miss most of the real punishing blows—the short, quick smashes landed in close.

Well, I went right after Brent, concentrating on his body. He was too kind of long and rangy to take much there. I hunched my shoulders, sunk my head on my hairy chest and bulled in, letting him pound my ears and the top of my head, while I slugged away with both hands for his heart and belly.

A left hook square under the liver made him gasp and sway like a mast in a high wind, but he desperately ripped in a right uppercut that caught me on the chin and kinda dizzied me for a instant. The gong found us fighting out of a clinch along the ropes.

My handler was highly enthusiastic, having bet a pound on me to win by a knockout. He nearly flattened a innocent ringsider showing me how to put over what he called “The Fitzsimmons Smoker.” I never heered of the punch.

Well, Bucko was good and mad and musta decided he couldn’t keep me away anyhow, so he come out of his corner like a bounding kangaroo, and swarmed all over me before I realized he’d changed his tactics. In a wild mix-up a fast, clever boxer can make a slugger look bad at his own game for a few seconds, being as the cleverer man can land quicker and oftener, but the catch is, he can’t keep up the pace. And the smashes the slugger lands are the ones which really counts.

The crowd went clean crazy when Bucko tore into me, ripping both hands to head and body as fast as he couldst heave one after the other. It looked like I was clean swamped, but them that knowed me tripled their bets. Brent wasn’t hurting me none—cutting me up a little, but he was hitting too fast to be putting much weight behind his smacks.

Purty soon I drove a glove through the flurry of his punches. His grunt was plainly heered all over the house. He shot both hands to my head and I come back with a looping left to the body which sunk in nearly up to the wrist.

It was kinda like a bull fighting a tiger, I reckon. He swarmed all over me, hitting fast as a cat claws, whilst I kept my head down and gored him in the belly occasionally. Them body punches was rapidly taking the steam outa him, together with the pace he was setting for hisself. His punches was getting more like slaps and when I seen his knees suddenly tremble, I shifted and crashed my right to his jaw with everything I had behind it. It was a bit high or he’d been out till yet.

Anyway, he done a nose dive and hadn’t scarcely quivered at “Nine,” when the gong sounded. Most of the crowd was howling lunatics. It looked to them like a chance blow, swung by a desperate, losing man, hadst dropped Bucko just when he was winning in a walk.

But the old-timers knowed better. I couldst see ’em lean back and wink at each other and nod like they was saying: “See, what did I tell you, huh?”

Bucko’s merry men worked over him and brung him up in time for the fourth round. In fact, they done a lot of work over him. They clustered around him till you couldn’t see what they was doing.

Well, he come out fairly fresh. He had good recuperating powers. He come out cautious, with his left hand stuck out. I noticed that they’d evidently spilt a lot of water on his glove; it was wet.

I glided in fast and he pawed at my face with that left. I didn’t pay no attention to it. Then when it was a inch from my eyes I smelt a peculiar, pungent kind of smell! I ducked wildly, but not quick enough. The next instant my eyes felt like somebody’d throwed fire into ’em. Turpentine! His left glove was soaked with it!

I’d caught at his wrist when I ducked. And now with a roar of rage, whilst I could still see a little, I grabbed his elbow with the other hand and, ignoring the smash he gimme on the ear with his right, I bent his arm back and rubbed his own glove in his own face.

He give a most ear-splitting shriek. The crowd bellered with bewilderment and astonishment and the referee rushed in to find out what was happening.

“I say!” he squawked, grabbing hold of us, as we was all tangled up by then. “Wot’s going on ’ere? I say, it’s disgryceful—Ow!”

By some mischance or other, Bucko, thinking it was me, or swinging blind, hit the referee right smack between the eyes with that turpentine-soaked glove.

Losing touch with my enemy, I got scared that he’d creep up on me and sock me from behind. I was clean blind by now and I didn’t know whether he was or not. So I put my head down and started swinging wild and reckless with both hands, on a chance I’d connect.

Meanwhile, as I heered afterward, Bucko, being as blind as I was, was doing the same identical thing. And the referee was going around the ring like a race horse, yelling for the cops, the army, the navy or what have you!

The crowd was clean off its nut, having no idee as to what it all meant.

“That blawsted blighter Brent!” howled the cavorting referee in response to the inquiring screams of the maniacal crowd. “ ’E threw vitriol in me blawsted h’eyes!”

“Cheer up, cull!” bawled some thug. “Both of ’em’s blind too!”

“ ’Ow can H’I h’officiate in this condition?” howled the referee, jumping up and down. “Wot’s tyking plyce in the bally ring?”

“Bucko’s just flattened one of his handlers which was climbin’ into the ring, with a blind swing!” the crowd whooped hilariously. “The Sailor’s gone into a clinch with a ring post!”

Hearing this, I released what I had thought was Brent, with some annoyance. Some object bumping into me at this instant, I took it to be Bucko and knocked it head over heels. The delirious howls of the multitude informed me of my mistake. Maddened, I plunged forward, swinging, and felt my left hook around a human neck. As the referee was on the canvas this must be Bucko, I thought, dragging him toward me, and he proved it by sinking a glove to the wrist in my belly.

I ignored this discourteous gesture, and, maintaining my grip on his neck, I hooked over a right with all I had. Having hold of his neck, I knowed about where his jaw oughta be, and I figgered right. I knocked Bucko clean outa my grasp and from the noise he made hitting the canvas I knowed that in the ordinary course of events, he was through for the night.

I groped into a corner and clawed some of the turpentine outa my eyes. The referee had staggered up and was yelling: “ ’Ow in the blinkin’ ’Ades can a man referee in such a mad-’ouse? Wot’s ’ere, wot’s ’ere?”

“Bucko’s down!” the crowd screamed. “Count him out!”

“W’ere is ’e?” bawled the referee, blundering around the ring.

“Three p’ints off yer port bow!” they yelled and he tacked and fell over the vaguely writhing figger of Bucko. He scrambled up with a howl of triumph and begun to count with the most vindictive voice I ever heered. With each count he’d kick Bucko in the ribs.

“—H’eight! Nine! Ten! H’and you’re h’out, you blawsted, blinkin’ blightin’, bally h’assassinatin’ pirate!” whooped the referee, with one last tremendjous kick.

I climb over the ropes and my handler showed me which way was my dressing-room. Ever have turpentine rubbed in your eyes? Jerusha! I don’t know of nothing more painful. You can easy go blind for good.

But after my handler hadst washed my eyes out good, I was all right. Collecting my earnings from Bulawayo, I set sail for the American Seamen’s Bar, where I was to meet Shifty Kerren and give him the money to pay Delrano’s fine with.

It was quite a bit past the time I’d set to meet Shifty, and he wasn’t nowhere to be seen. I asked the barkeep if he’d been there and the barkeep, who knowed Shifty, said he’d waited about half an hour and then hoisted anchor. I ast the barkeep if he knowed where he lived and he said he did and told me. So I ast him would he keep Mike till I got back and he said he would. Mike despises Delrano so utterly I was afraid I couldn’t keep him away from the Kid’s throat, if we saw him, and I figgered on going down to the jail with Shifty.

Well, I went to the place the bartender told me and went upstairs to the room the landlady said Shifty had, and started to knock when I heard men talking inside. Sounded like the Kid’s voice, but I couldn’t tell what he was saying so I knocked and somebody said: “Come in.”

I opened the door. Three men was sitting there playing pinochle. They was Shifty, Bill Slane, the Kid’s sparring partner, and the Kid hisself.

“Howdy, Steve,” said Shifty with a smirk, kinda furtive eyed, “whatcha doin’ away up here?”

“Why,” said I, kinda took aback, “I brung the dough for the Kid’s fine, but I see he don’t need it, bein’ as he’s out.”

Delrano hadst been craning his neck to see if Mike was with me, and now he says, with a nasty sneer: “What’s the matter with your face, Costigan? Some street kid poke you on the nose?”

“If you wanta know,” I growled, “I got these marks on your account. Shifty told me you was in stir, and I was broke, so I fought down at The South African to get fine-money.”

At that the Kid and Slane bust out into loud and jeering laughter—not the kind you like to hear. Shifty joined in, kinda nervous-like.

“Whatcha laughin’ at?” I snarled. “Think I’m lyin’?”

“Naw, you ain’t lyin’,” mocked the Kid. “You ain’t got sense enough to. You’re just the kind of a dub that would do somethin’ like that.”

“You see, Steve,” said Shifty, “the Kid—”

“Aw shut up, Shifty!” snapped Delrano. “Let the big sap know he’s been took for a ride. I’m goin’ to tell him what a sucker he’s been. He ain’t got his blasted bulldog with him. He can’t do nothin’ to the three of us.”

Delrano got up and stuck his sneering, pasty white face up close to mine.

“Of all the dumb, soft, boneheaded boobs I ever knew,” said he, and his tone cut like a whip lash, “you’re the limit. Get this, Costigan, I ain’t broke and I ain’t been in jail! You want to know why Shifty spilt you that line? Because I bet him ten dollars that much as you hate me and him, we could hand you a hard luck tale and gyp you outa your last cent.

“Well, it worked! And to think that you been fightin’ for the dough to give me! Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha! You big chump! You’re a natural born sucker! You fall for anything anybody tells you. You’ll never get nowheres. Look at me—I wouldn’t give a blind man a penny if he was starvin’ and my brother besides. But you—oh, what a sap!

“If Shifty hadn’t been so anxious to win that ten bucks that he wouldn’t wait down at the bar, we’d had your dough, too. But this is good enough. I’m plenty satisfied just to know how hard you fell for our graft, and to see how you got beat up gettin’ money to pay my fine! Ha-ha-ha!”

By this time I was seeing them through a red mist. My huge fists was clenched till the knuckles was white, and when I spoke it didn’t hardly sound like my voice at all, it was so strangled with rage.

“They’s rats in every country,” I ground out. “If you’d of picked my pockets or slugged me for my dough, I coulda understood it. If you’d worked a cold deck or crooked dice on me, I wouldn’ta kicked. But you appealed to my better nature, ’stead of my worst.

“You brung up a plea of patriotism and national fellership which no decent man woulda refused. You appealed to my natural pride of blood and nationality. It wasn’t for you I done it—it wasn’t for you I spilt my blood and risked my eyesight. It was for the principles and ideals you’ve mocked and tromped into the muck—the honor of our country and the fellership of Americans the world over.

“You dirty swine! You ain’t fitten to be called Americans. Thank gosh, for everyone like you, they’s ten thousand decent men like me. And if it’s bein’ a sucker to help out a countryman when he’s in a jam in a foreign land, then I thanks the Lord I am a sucker. But I ain’t all softness and mush—feel this here for a change!”

And I closed the Kid’s eye with a smashing left hander. He give a howl of surprise and rage and come back with a left to the jaw. But he didn’t have a chance. He’d licked me in the ring, but he couldn’t lick me bare-handed, in a small room where he couldn’t keep away from my hooks, not even with two men to help him. I was blind mad and I just kind of gored and tossed him like a charging bull.

If he hit at all after that first punch I don’t remember it. I know I crashed him clean across the room with a regular whirlwind of smashes, and left him sprawled out in the ruins of three or four chairs with both eyes punched shut and his arm broke. I then turned on his cohorts and hit Bill Slane on the jaw, knocking him stiff as a wedge. Shifty broke for the door, but I pounced on him and spilled him on his neck in a corner with a open-handed slap.

I then stalked forth in silent majesty and gained the street. As I went I was filled with bitterness. Of all the dirty, contemptible tricks I ever heered of, that took the cake. And I got to thinking maybe they was right when they said I was a sucker. Looking back, it seemed to me like I’d fell for every slick trick under the sun. I got mad. I got mighty mad.

I shook my fist at the world in general, much to the astonishment and apprehension of the innocent by-passers.

“From now on,” I raged, “I’m harder’n the plate on a battleship! I ain’t goin’ to fall for nothin’! Nobody’s goin’ to get a blasted cent outa me, not for no reason what-the-some-ever—”

At that moment I heered a commotion going on nearby. I looked. Spite of the fact that it was late, a pretty good-sized crowd hadst gathered in front of a kinda third-class boarding-house. A mighty purty blonde-headed girl was standing there, tears running down her cheeks as she pleaded with a tough-looking old sister who stood with her hands on her hips, grim and stern.

“Oh, please don’t turn me out!” wailed the girl. “I have no place to go! No job—oh, please. Please!”

I can’t stand to hear a hurt animal cry out or a woman beg. I shouldered through the crowd and said: “What’s goin’ on here?”

“This hussy owes me ten pounds,” snarled the woman. “I got to have the money or her room. I’m turnin’ her out.”

“Where’s her baggage?” I asked.

“I’m keepin’ it for the rent she owes,” she snapped. “Any of your business?”

The girl kind of slumped down in the street. I thought if she’s turned out on the street tonight they’ll be hauling another carcass outa the bay tomorrer. I said to the landlady, “Take six pounds and call it even.”

“Ain’t you got no more?” said she.

“Naw, I ain’t,” I said truthfully.

“All right, it’s a go,” she snarled, and grabbed the dough like a sea-gull grabs a fish.

“All right,” she said very harshly to the girl, “you can stay another week. Maybe you’ll find a job by that time—or some other sap of a Yank sailor will come along and pay your board.”

She went into the house and the crowd give a kind of cheer which inflated my chest about half a foot. Then the girl come up close to me and said shyly, “Thank you. I—I—I can’t begin to tell you how much I appreciate what you’ve done for me.”

Then all to a sudden she throwed her arms around my neck and kissed me and then run up the steps into the boarding-house. The crowd cheered some more like British crowds does and I felt plenty uplifted as I swaggered down the street. Things like that, I reflected, is worthy causes. A worthy cause can have my dough any time, but I reckon I’m too blame smart to get fooled by no shysters.

I come into the American Seamen’s Bar where Mike was getting anxious about me. He wagged his stump of a tail and grinned all over his big wide face and I found two American nickels in my pocket which I didn’t know I had. I give one of ’em to the barkeep to buy a pan of beer for Mike. And whilst he was lapping it, the barkeep, he said: “I see Boardin’-house Kate is in town.”

“Whatcha mean?” I ast him.

“Well,” said he, combing his mustache, “Kate’s worked her racket all over Australia and the West Coast of America, but this is the first time I ever seen her in South Africa. She lets some landlady of a cheap boardin’-house in on the scheme and this dame pretends to throw her out. Kate puts up a wail and somebody—usually some free-hearted sailor about like you—happens along and pays the landlady the money Kate’s supposed to owe for rent so she won’t kick the girl out onto the street. Then they split the dough.”

“Uh huh!” said I, grinding my teeth slightly. “Does this here Boardin’-house Kate happen to be a blonde?”

“Sure thing,” said the barkeep. “And purty as hell. What did you say?”

“Nothin’,” I said. “Here. Give me a schooner of beer and take this nickel, quick, before somebody comes along and gets it away from me.”