Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

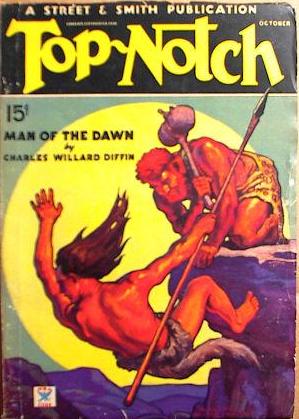

Published in Top-Notch, Vol. 95, No. 4 (October 1934).

| Chapter I Chapter II |

Chapter III Chapter IV |

Kirby O’Donnell opened his chamber door and gazed out, his long keen-bladed kindhjal in his hand. Somewhere a cresset glowed fitfully, dimly lighting the broad hallway, flanked by thick columns. The spaces between these columns were black arched wells of darkness, where anything might be lurking.

Nothing moved within his range of vision. The great hall seemed deserted. But he knew that he had not merely dreamed that he heard the stealthy pad of bare feet outside his door, the stealthy sound of unseen hands trying the portal.

O’Donnell felt the peril that crawled unseen about him, the first white man ever to set foot in forgotten Shahrazar, the forbidden, age-old city brooding high among the Afghan mountains. He believed his disguise was perfect; as Ali el Ghazi, a wandering Kurd, he had entered Shahrazar, and as such he was a guest in the palace of its prince. But the furtive footfalls that had awakened him were a sinister portent.

He stepped out into the hall cautiously, closing the door behind him. A single step he took—it was the swish of a garment that warned him. He whirled, quick as a cat, and saw, all in a split second, a great black body, hurtling at him from the shadows, the gleam of a plunging knife. And simultaneously he himself moved in a blinding blur of speed. A shift of his whole body avoided the stroke, and as the blade licked past, splitting only thin air, his kindhjal, driven with desperate energy, sank its full length in the black torso.

An agonized groan was choked by a rush of blood in the dusky throat. The Negro’s knife rang on the marble floor, and the great black figure, checked in its headlong rush, swayed drunkenly and pitched forward. O’Donnell watched with his eyes as hard as flint as the would-be murderer shuddered convulsively and then lay still in a widening crimson pool.

He recognized the man, and as he stood staring down at his victim, a train of associations passed swiftly through his mind, recollections of past events crowding on a realization of his present situation.

Lure of treasure had brought O’Donnell in his disguise to forbidden Shahrazar. Since the days of Genghis Khan, Shahrazar had sheltered the treasure of the long-dead shahs of Khuwarezm. Many an adventurer had sought that fabled hoard, and many had died. But O’Donnell had found it—only to lose it.

Hardly had he arrived in Shahrazar when a band of marauding Turkomans, under their chief, Orkhan Bahadur, had stormed the city and captured it, slaying its prince, the Uzbek Shaibar Khan. And while the battle raged in the streets, O’Donnell had found the hidden treasure in a secret chamber, and his brain had reeled at its splendor. But he had been unable to bear it away, and he dared not leave it for Orkhan. The emissary of an intriguing European power was in Shahrazar, plotting to use that treasure to conquer India. O’Donnell had done away with it forever. The victorious Turkomans had searched for it in vain.

O’Donnell, as Ali el Ghazi, had once saved Orkhan Bahadur’s life, and the prince made the supposed Kurd welcome in the palace. None dreamed of his connection with the disappearance of the hoard, unless—O’Donnell stared somberly down at the figure on the marble floor.

That man was Baber, a Soudani servant of Suleiman Pasha, the emissary.

O’Donnell lifted his head and swept his gaze over the black arches, the shadowy columns. Had he only imagined that he heard movement back in the darkness? Bending over quickly, he grasped the limp body and heaved it on his shoulder—an act impossible for a man with less steely thews—and started down the hall. A corpse found before his door meant questions, and the fewer questions O’Donnell had to answer the better.

He went down the broad, silent hall and descended a wide marble stair into swallowing gloom, like an oriental demon carrying a corpse to hell; groped through a tapestried door and down a short, black corridor to a blank marble wall.

When he thrust against this with his foot, a section swung inward, working on a pivot, and he entered a circular, domed chamber with a marble floor and walls hung with heavy gilt-worked tapestries, between which showed broad golden-frieze work. A bronze lamp cast a soft light, making the dome seem lofty and full of shadows, while the tapestries were clinging squares of velvet darkness.

This had been the treasure vault of Shaibar Khan, and why it was empty now, only Kirby O’Donnell could tell.

Lowering the black body with a gasp of relief, for the burden had taxed even his wiry thews to the utmost, he desposited it exactly on the great disk that formed the center of the marble floor. Then he crossed the chamber, seized a gold bar that seemed merely part of the ornamentation, and jerked it strongly. Instantly the great central disk revolved silently, revealing a glimpse of a black opening, into which the corpse tumbled. The sound of rushing water welled up from the darkness, and then the slab, swinging on its pivot, completed its revolution and the floor showed again a smooth unbroken surface.

But O’Donnell wheeled suddenly. The lamp burned low, filling the chamber with a lurid unreal light. In that light he saw the door open silently and a slim dark figure glide in.

It was a slender man with long nervous hands and an ivory oval of a face, pointed with a short black beard. His eyes were long and oblique, his garments dark, even his turban. In his hand a blue, snub-nosed revolver glinted dully.

“Suleiman Pasha!” muttered O’Donnell tensely.

He had never been able to decide whether this man was the Oriental he seemed, or a European in masquerade. Had the man penetrated his own disguise? The emissary’s first words assured him that such was not the case.

“Ali el Ghazi,” said Suleiman, “you have lost me a valuable servant, but you have told me a secret. None other knows the secret of that revolving slab. I did not, until I followed you, after you killed Baber, and watched you through the door, though I have suspected that this chamber was the treasure vault.

“I have suspected you—now I am certain. I know why the treasure has never been found. You disposed of it as you have disposed of Baber. You are cup-companion to Prince Orkhan Bahadur. But if I told him you cast away the treasure forever, do you suppose his friendship would prevail over his wrath?

“Keep back!” he warned. “I did not say that I would tell Orkhan. Why you threw away the treasure I cannot guess, unless it was because of fanatical loyalty to Shaibar Kahn.”

He looked him over closely. “Face like a hawk, body of coiled steel springs,” he murmured. “I can use you, my Kurdish swaggerer.”

“How use me?” demanded O’Donnell.

“You can help me in the game I play with Orkhan Bahadur. The treasure is gone, but I can still use him, I and the Feringis who employ me. I will make him amir of Afghanistan and, after that, sultan of India.”

“And the puppet of the Feringis,” grunted O’Donnell.

“What is that to thee?” Suleiman laughed. “Time is not to think. I will do the thinking; see thou to the enacting of my commands.”

“I have not said that I would serve you,” growled O’Donnell doggedly.

“You have no other choice,” answered Suleiman calmly. “If you refuse, I will reveal to Orkhan that which I learned tonight, and he will have you flayed alive.”

O’Donnell bent his head moodily. He was caught in a vise of circumstances. It had not been loyalty to Shaibar Kahn, as Suleiman thought, which had caused him to dump an emperor’s ransom in gold and jewels into the subterranean river. He knew Suleiman plotted the overthrow of British rule in India and the massacre of the helpless millions. He knew that Orkhan Bahadur, a ruthless adventurer despite his friendship for the false Kurd, was a pliant tool in the emissary’s hands. The treasure had been too potent a weapon to leave within their reach.

Suleiman was either a Russian or the Oriental tool of the Russians. Perhaps he, too, had secret ambitions. The Khuwarezm treasure had been a pawn in his game; but, even without it, a tool of the emissary’s sitting on the throne of Shahrazar, was a living menace to the peace of India. So O’Donnell had remained in the city, seeking in every way to thwart Suleiman’s efforts to dominate Orkhan Bahadur. And now he himself was trapped.

He lifted his head and stared murderously at the slim Oriental. “What do you wish me to do?” he muttered.

“I have a task for you,” answered Suleiman. “An hour ago word came to me, by one of my secret agents, that the tribesmen of Khuruk had found an Englishman dying in the hills, with valuable papers upon him. I must have those papers. I sent the man on to Orkhan, while I dealt with you.

“But I have changed my plans in regard to you; you are more valuable to me alive than dead, since there is no danger of your opposing me in the future. Orkhan will desire those papers that the Englishman carried, for the man was undoubtedly a secret-service agent, and I will persuade the prince to send you with a troop of horsemen to secure them. And remember you are taking your real orders from me, not from Orkhan.”

He stepped aside and motioned O’Donnell to precede him.

They traversed the short corridor, an electric torch in Suleiman’s left hand playing its beam on his sullen, watchful companion, climbed the stair and went through the wide hall, thence along a winding corridor and into a chamber where Orkhan Bahadur stood near a gold-barred window which opened onto an arcaded court, which was just being whitened by dawn. The prince of Shahrazar was resplendent in satin and pearl-sewn velvet which did not mask the hard lines of his lean body.

His thin dark features lighted at the sight of his cup-companion, but O’Donnell reflected on the wolf that lurked ever below the surface of this barbaric chieftain, and how suddenly it could be unmasked, snarling and flame-eyed.

“Welcome, friends!” said the Turkoman, pacing the chamber restlessly. “I have heard a tale! Three days’ ride to the southwest are the villages of Ahmed Shah, in the valley of Khuruk. Four days ago his men came upon a man dying in the mountains. He wore the garments of an Afghan, but in his delirium he revealed himself as an Englishman. When he was dead they searched him for loot and found certain papers which none of the dogs could read.

“But in his ravings he spoke of having been to Bowhara. It is in my mind that this Feringi was an English spy, returning to India with papers valuable to the sirkar. Perhaps the British would pay well for these papers, if they knew of them. It is my wish to possess them. Yet I dare not ride forth myself, nor send many men. Suppose the treasure was found in my absence? My own men would bar the gates against me.”

“This is a matter for diplomacy rather than force,” put in Suleiman Pasha smoothly. “Ali el Ghazi is crafty as well as bold. Send him with fifty men.”

“Can thou do it, brother?” demanded Orkhan eagerly. Suleiman’s gaze burned into O’Donnell’s soul. There was but one answer, if he wished to escape flaying steel and searing fire.

“Only in Allah is power,” he muttered. “Yet I can attempt the thing.”

“Mashallah!” exclaimed Orkhan. “Be ready to start within the hour. There is a Khurukzai in the suk, one Dost Shah, who is of Ahmed’s clan, and will guide you. There is friendship between me and the men of Khuruk. Approach Ahmed Shah in peace and offer him gold for the papers, but not too much, lest his cupidity be roused. But I leave it to your own judgement. With fifty men there is no fear of the smaller clans between Shahrazar and Khuruk. I go now to choose the men to ride with you.”

As soon as Orkhan left the chamber, Suleiman bent close to O’Donnell and whispered: “Secure the papers, but do not bring them to Orkhan! Pretend that you have lost them in the hills—anything—but bring them to me.”

“Orkhan will be angry and suspicious,” objected O’Donnell.

“Not half as angry as he would be if he knew what became of the Khuwarezm treasure,” retorted Suleiman. “Your only chance is to obey me. If your men return without you, saying you have fled away, be sure a hundred men will quickly be upon your trail—nor can you hope to win alone through these hostile, devil-haunted hills, anyway. Do not dare to return without the papers, if you do not wish to be denounced to Orkhan. Your life depends on your playing my game, Kurd!”

Playing Suleiman’s “game” seemed to be the only thing to do, even three days later as O’Donnell, in his guise of the Kurdish swashbuckler, Ali el Ghazi, was riding along a trail that followed a ledgelike fold of rock ribbing a mile-wide cliff.

Just ahead of him on a bony crowbait rode the Khurukzai guide, a hairy savage with a dirty white turban, and behind him strung out in single file fifty of Orkhan Bahadur’s picked warriors. O’Donnell felt the pride of a good leader of fighting men as he glanced back at them. These were no stunted peasants, but tall, sinewy men with the pride and temper of hawks; nomads and sons of nomads, born to the saddle. They rode horses that were distinctive in that land of horsemen, and their rifles were modern repeaters.

“Listen!” It was the Khurukzai who halted, suddenly, lifting a hand in warning.

O’Donnell leaned forward, rising in the wide silver stirrups, turning his head slightly sidewise. A gust of wind whipped along the ledge, bearing with it the echoes of a series of sputtering reports.

The men behind O’Donnell heard it, too, and there was a creaking of saddles as they instinctively unslung rifles and hitched yataghan hilts forward.

“Rifles!” exclaimed Dost Shah. “Men are fighting in the hills.”

“How far are we from Khuruk?” asked O’Donnell.

“An hour’s ride,” answered the Khurukzai, glancing at the mid-afternoon sun. “Beyond the corner of the cliff we can see the Pass of Akbar, which is the boundary of Ahmed Shah’s territory. Khuruk is some miles beyond.”

“Push on, then,” said O’Donnell.

They moved on around the crag which jutted out like the prow of a ship, shutting off all view to the south. The path narrowed and sloped there, so the men dismounted and edged their way, leading the animals which grew half frantic with fear.

Ahead of them the trail broadened and sloped up to a fan-shaped plateau, flanked by rugged ridges. This plateau narrowed to a pass in a solid wall of rock hundreds of feet high; the pass was a triangular gash, and a stone tower in its mouth commanded the approach. There were men in the tower, and they were firing at other men who lay out on the plateau in a wide ragged crescent, concealed behind boulders and rocky ledges. But these were not all firing at the tower, as it presently became apparent.

Off to the left of the pass, skirting the foot of the cliffs, a ravine meandered. Men were hiding in this ravine, and O’Donnell quickly saw that they were trapped there. The men out on the plateau had cast a cordon around it and were working their way closer, shooting as they came. The men in the ravine fired back, and a few corpses were strewn among the rocks. But from the sound of the firing, there were only a few men in the gully, and the men in the tower could not come to their aid. It would have been suicide to try to cross that bullet-swept open space between the ravine and the pass mouth.

O’Donnell had halted his men at an angle of the cliff where the trail wound up toward the plateau, and had advanced with the Khurukzai guide part way up the incline.

“What does this mean?” he asked.

Dost Shah shook his head like one puzzled. “That is the Pass of Akbar,” he said. “That tower is Ahmed Shah’s. Sometimes the tribes come to fight us, and we shoot them from the tower. It can only be Ahmed’s riflemen in the tower and in the ravine. But—-”

He shook his head again, and having tied his horse to a straggling tamarisk, he went up the slope, craning his neck and hugging his rifle, while he muttered in his beard as if in uncertainty.

O’Donnell followed him to the crest where the trail bent over the rim of the plateau, but with more caution than the Khurukzai was showing. They were now within rifle range of the combatants, and bullets were whistling like hornets across the plateau.

O’Donnell could plainly make out the forms of the besiegers lying among the rocks that littered the narrow plain. Evidently they had not noticed him and the guide, and he did not believe they saw his men where he had stationed them in the shade of an overhanging crag. All their attention was fixed on the ravine, and they yelled with fierce exultation as a turban thrust above its rim fell back splashed with crimson. The men in the tower yelled with helpless fury.

“Keep your head down, you fool!” O’Donnell swore at Dost Shah, who was carelessly craning his long neck above a cluster of rocks.

“The men in the tower must be Ahmed’s men,” muttered Dost Shah uneasily. “Yes; it could not be otherwise, yet—Allah!” The last was an explosive yelp, and he sprang up like a madman, as if forgetting all caution in some other overwhelming emotion.

O’Donnell cursed and grabbed at him to pull him down, but he stood brandishing his rifle, his tattered garments whipping in the wind like a demon of the hills.

“What devil’s work is this?” he yelled. “That is not—those are not—-”

His voice changed to a gasp as a bullet drilled him through the temple. He tumbled back to the ground and lay without motion.

“Now what was he going to say?” muttered O’Donnell, peering, out over the rocks. “Was that a stray slug, or did somebody see him?”

He could not tell whether the shot came from the boulders or the tower. It was typical of hill warfare, the yells and shooting keeping up an incessant devil’s din. One thing was certain: the cordon was gradually closing about the men trapped in the ravine. They were well hidden from the bullets, but the attackers were working so close that presently they could finish the job with a short swift rush and knife work at close quarters.

O’Donnell fell back down the incline, and coming to the eager Turkomans, spoke hurriedly: “Dost Shah is dead, but he has brought us to the borders of Ahmed Shah’s territory. Those in the tower are Khurukzai, and these men attacking them have cut off some chief—probably Ahmed Shah himself—in that ravine. I judge that from the noise both sides are making. Then, they’d scarcely be taking such chances to slaughter a few common warriors. If we rescue him we shall have a claim on his friendship, and our task will be made easy, as Allah makes all things for brave men.

“The men attacking seem to me not to number more than a hundred men—twice our number, true, but there are circumstances in our favor, surprise, and the fact that the men in the pass will undoubtedly sally out if we create a diversion in the enemy’s rear. At present the Khurukzai are bottled in the pass. They cannot emerge, any more than the raiders can enter in the teeth of their bullets.”

“We await orders,” the men answered.

Turkomans have no love for Kurds, but the horsemen knew that Ali el Ghazi was cup-companion to their prince.

“Ten men to hold the horses!” he snapped. “The rest follow me.”

A few minutes later they were crawling after him up the short slope. He lined them along the crest, seeing that each man was sheltered among the boulders.

This took but a few minutes, but in that interim the men crawling toward the ravine sprang to their feet and tore madly across the intervening space, yelling like blood-crazed wolves, their curved blades glittering in the sun. Rifles spat from the gully and three of the attackers dropped, and the men in the tower sent up an awful howl and turned their guns desperately on the charging mob. But the range at that angle was too great.

Then O’Donnell snapped an order, and a withering line of flame ran along the crest of the ridge. His men were picked marksmen and understood the value of volleys. Some thirty men were in the open, charging the ravine. A full half of them went down struck from behind, as if by some giant invisible fist. The others halted, realizing that something was wrong; they cringed dazedly, turning here and there, grasping their long knives, while the bullets of the Turkomans took further toll.

Then, suddenly, realizing that they were being attacked from the rear, they dived screaming for cover. The men in the tower, sensing reinforcements, sent up a wild shout and redoubled their fire.

The Turkomans, veterans of a hundred wild battles, hugged their boulders and kept aiming and firing without the slightest confusion. The men on the plateau were kicking up the devil’s own din. They were caught in the jaws of the vise, with bullets coming from both ways, and no way of knowing the exact numbers of their new assailants.

The break came with hurricane suddenness, as is nearly always the case in hill fighting. The men on the plain broke and fled westward, a disorderly mob, scrambling over boulders and leaping gullies, their tattered garments flapping in the wind.

The Turkomans sent a last volley into their backs, toppling over distant figures like tenpins, and the men in the tower gave tongue and began scrambling down into the pass.

O’Donnell cast a practised eye at the fleeing marauders, knew that the rout was final, and called for the ten men below him to bring up the horses swiftly. He had an eye for dramatics, and he knew the effect they would make filing over the ridge and out across the boulder-strewn plain on their Turkish steeds.

A few minutes later he enjoyed that effect and the surprised yells of the men they had aided as they saw the Astrakhan Kalpaks of the riders top the ridge. The pass was crowded with men in ragged garments, grasping rifles, and in evident doubt as to the status of the newcomers.

O’Donnell headed straight for the ravine, which was nearer the ridge than it was to the pass, believing the Khurukzai chief was among those trapped there.

His rifle was slung on his back, and his open right hand raised as a sign of peace; seeing which the men in the pass dubiously lowered their rifles and came streaming across the plateau toward him, instead of pursuing the vanquished, who were already disappearing among the distant crags and gulches.

A dozen steps from the edge of the ravine O’Donnell drew rein, glimpsing turbans among the rocks, and called out a greeting in Pashtu. A deep bellowing voice answered him, and a vast figure heaved up into full view, followed by half a dozen lesser shapes.

“Allah be with thee!” roared the first man.

He was tall, broad, and powerful; his beard was stained with henna, and his eyes blazed like fires burning under gray ice. One massive fist gripped a rifle, the thumb of the other was hooked into the broad silken girdle which banded his capacious belly, as he tilted back on his heels and thrust his beard out truculently. That girdle likewise supported a broad tulwar and three or four knives.

“Mashallah!” roared this individual. “I had thought it was my own men who had taken the dogs in the rear, until I saw those fur caps. Ye are Turks from Shahrazar, no doubt?”

“Aye; I am Ali el Ghazi, a Kurd, brother-in-arms to Orkhan Bahadur. You are Ahmed Shah, lord of Khuruk?”

There was a hyena-like cackle of laughter from the lean, evil-eyed men who had followed the big man out of the gully.

“Ahmed Shah has been in hell these four days,” rumbled the giant. “I am Afzal Khan, whom men name the Butcher.”

O’Donnell sensed rather than heard a slight stir among the men behind him. Most of them understood Pashtu, and the deeds of Afzal Khan had found echo in the serais of Turkestan. The man was an outlaw, even in that lawless land, a savage plunderer whose wild road was lurid with the smoke and blood of slaughter.

“But that pass is the gateway to Khuruk,” said O’Donnell, slightly bewildered.

“Aye!” agreed Afzal Khan affably. “Four days ago I came down into the valley from the east and drove out the Khurukzai dogs. Ahmed Shah I slew with my own hands—so!”

A flicker of red akin to madness flamed up momentarily in his eyes as he smashed the butt of his rifle down on a dead tamarisk branch, shattering it from the trunk. It was as if the mere mention of murder roused the sleeping devil in him. Then his beard bristled in a fierce grin.

“The villages of Khuruk I burned,” he said calmly. “My men need no roofs between them and the sky. The village dogs—such as still lived—fled into the hills. This day I was hunting some from among the rocks, not deeming them wise enough to plant an ambush, when they cut me off from the pass, and the rest you know. I took refuge in the ravine. When I heard your firing I thought it was my own men.”

O’Donnell did not at once answer, but sat his horse, gazing inscrutably at the fierce, scarred countenance of the Afghan. A sidelong glance showed him the men from the tower straggling up—some seventy of them, a wild, dissolute band, ragged and hairy, with wolfish countenances and rifles in their hands. These rifles were, in most cases, inferior to those carried by his own men.

In a battle begun then and there, the advantage was still with the mounted Turkomans. Then another glance showed him more men swarming out of the pass—a hundred at least.

“The dogs come at last!” grunted Afzal Khan. “They have been gorging back in the valley. I would have been vulture bait if I had been forced to await their coming. Brother!” He strode forward to lay his hand on O’Donnell’s stirrup strap, while envy of the admiration for the magnificent Turkish stallion burned in his fierce eyes. “Brother, come with me to Khuruk! You have saved my life this day, and I would reward you fittingly.”

O’Donnell did not look at his Turkomans. He knew they were waiting for his orders and would obey him. He could draw his pistol and shoot Afzal Kahn dead, and they could cut their way back across the plateau in the teeth of the volleys that were sure to rake their line of flight. Many would escape. But why escape? Afzal Khan had every reason to show them the face of a friend, and, besides, if he had killed Ahmed Shah, it was logical to suppose that he had the papers without which O’Donnell dared not return to Shahrazar.

“We will ride with you to Khuruk, Afzal Khan,” decided O’Donnell.

The Afghan combed his crimson beard with his fingers and boomed his gratification.

The ragged ruffians closed in about them as they rode toward the pass, a swarm of sheepskin coats and soiled turbans that hemmed in the clean-cut riders in their fur caps and girdled kaftans.

O’Donnell did not miss the envy in the glances cast at the rifles and cartridge belts and horses of the Turkomans. Orkhan Bahadur was generous with his men to the point of extravagance; he had sent them out with enough ammunition to fight a small war.

Afzal Khan strode by O’Donnell’s stirrup, booming his comments and apparently oblivious to everything except the sound of his own voice.

O’Donnell glanced from him to his followers. Afzal Khan was a Yusufzai, a pure-bred Afghan, but his men were a motley mob—Pathans, mostly, Orakzai, Ummer Khels, Sudozai, Afridis, Ghilzai—outcasts and nameless men from many tribes.

They went through the pass—a knifecut gash between sheer rock walls, forty feet wide and three hundred yards long—and beyond the tower were a score of gaunt horses which Afzal Khan and some of his favored henchmen mounted. Then the chief gave pungent orders to his men; fifty of them climbed into the tower and resumed the ceaseless vigilance that is the price of life in the hills, and the rest followed him and his guests out of the pass and along the knife-edge trail that wound amid savage crags and jutting spurs.

Afzal Khan fell silent, and indeed there was scant opportunity for conversation, each man being occupied in keeping his horse or his own feet on the wavering path. The surrounding crags were so rugged and lofty that the strategic importance of the Pass of Akbar impressed itself still more strongly on O’Donnell.

Only through that pass could any body of men make their way safely. He felt uncomfortably like a man who sees a door shut behind him, blocking his escape, and he glanced furtively at Afzal Khan, riding with stirrups so short that he squatted like a huge toad in his saddle. The chief seemed preoccupied; he gnawed a wisp of his red beard and there was a blank stare in his eyes.

The sun was swinging low when they came to a second pass. This was not exactly a pass at all, in the usual sense. It was an opening in a cluster of rocky spurs that rose like fangs along the lip of a rim beyond which the land fell away in a long gradual sweep. Threading among these stony teeth, O’Donnell looked down into the valley of Khuruk.

It was not a deep valley, but it was flanked by cliffs that looked unscalable. It ran east and west, roughly, and they were entering it at the eastern end. At the western end it seemed to be blocked by a mass of crags.

There were no cultivated patches, or houses to be seen in the valley—only stretches of charred ground. Evidently the destruction of the Khurukzai villages had been thorough. In the midst of the valley stood a square stone inclosure, with a tower at one corner, such as are common in the hills, and serve as forts in times of strife.

Divining his thought, Afzal Khan pointed to this and said: “I struck like a thunderbolt. They had not time to take refuge in the sangar. Their watchmen on the heights were careless. We stole upon them and knifed them; then in the dawn we swept down on the villages. Nay, some escaped. We could not slay them all. They will keep coming back to harass me—as they have done this day—until I hunt them down and wipe them all out.”

O’Donnell had not mentioned the papers; to have done so would have been foolish; he could think of no way to question Afzal Khan without waking the Afghan’s suspicions; he must await his opportunity.

That opportunity came unexpectedly.

“Can you read Urdu?” asked Afzal Khan abruptly.

“Aye!” O’Donnell made no further comment but waited with concealed tenseness.

“I cannot; nor Pashtu, either, for that matter,” rumbled the Afghan. “There were papers on Ahmed Shah’s body, which I believe are written in Urdu.”

“I might be able to read them for you.”

O’Donnell tried to speak casually, but perhaps he was not able to keep his eagerness altogether out of his voice. Afzal Khan tugged his beard, glanced at him sidewise, and changed the subject. He spoke no more of the papers and made no move to show them to his guest. O’Donnell silently cursed his own impatience; but at least he had learned that the documents he sought were in the bandit’s possession, and that Afzal Khan was ignorant of their nature—if he was not lying.

At a growled order all but sixty of the chief’s men halted among the spurs overlooking the valley. The rest trailed after him.

“They watch for the Khurukzai dogs,” he explained. “There are trails by which a few men might get through the hills, avoiding the Pass of Akbar, and reach the head of the valley.”

“Is this the only entrance to Khuruk?”

“The only one that horses can travel. There are footpaths leading through the crags from the north and the south, but I have men posted there as well. One rifleman can hold any one of them forever. My forces are scattered about the valley. I am not to be taken by surprise as I took Ahmed Shah.”

The sun was sinking behind the western hills as they rode down the valley, tailed by the men on foot. All were strangely silent, as if oppressed by the silence of the plundered valley. Their destination evidently was the inclosure, which stood perhaps a mile from the head of the valley. The valley floor was unusually free of boulders and stones, except a broken ledge like a reef that ran across the valley several hundred yards east of the fortalice. Halfway between these rocks and the inclosure, Afzal Khan halted.

“Camp here!” he said abruptly, with a tone more of command than invitation. “My men and I occupy the sangar, and it is well to keep our wolves somewhat apart. There is a place where your horses can be stabled, where there is plenty of fodder stored.” He pointed out a stone-walled pen of considerable dimensions a few hundred yards away, near the southern cliffs. “Hungry wolves come down from the gorges and attack the horses.”

“We will camp beside the pen,” said O’Donnell, preferring to be closer to their mounts.

Afzal Khan showed a flash of irritation. “Do you wish to be shot in the dark for an enemy?” he growled. “Pitch your tents where I bid you. I have told my men at the pass where you will camp, and if any of them come down the valley in the dark, and hear men where no men are supposed to be, they will shoot first and investigate later. Beside, the Khurukzai dogs, if they creep upon the crags and see men sleeping beneath them, will roll down boulders and crush you like insects.”

This seemed reasonable enough, and O’Donnell had no wish to antagonize Afzal Khan. The Afghan’s attitude seemed a mixture of his natural domineering arrogance and an effort at geniality. This was what might be expected, considering both the man’s nature and his present obligation. O’Donnell believed that Afzal Khan begrudged the obligation, but recognized it.

“We have no tents,” answered the American. “We need none. We sleep in our cloaks.” And he ordered his men to dismount at the spot designated by the chief. They at once unsaddled and led their horses to the pen, where, as the Afghan had declared, there was an abundance of fodder.

O’Donnell told off five men to guard them. Not, he hastened to explain to the frowning chief, that they feared human thieves, but there were the wolves to be considered. Afzal Khan grunted and turned his own sorry steeds into the pen, growling in his beard at the contrast they made alongside the Turkish horses.

His men showed no disposition to fraternize with the Turkomans; they entered the inclosure and presently the smoke of cooking fires arose. O’Donnell’s own men set about preparing their scanty meal, and Afzal Khan came and stood over them, combing his crimson beard that the firelight turned to blood. The jeweled hilts of his knives gleamed in the glow, and his eyes burned red like the eyes of a hawk.

“Our fare is poor,” he said abruptly. “Those Khurukzai dogs burned their own huts and food stores when they fled before us. We are half starved. I can offer you no food, though you are my guests. But there is a well in the sangar, and I have sent some of my men to fetch some steers we have in a pen outside the valley. Tomorrow we shall all feast full, inshallah!”

O’Donnell murmured a polite response, but he was conscious of a vague uneasiness. Afzal Khan was acting in a most curious manner, even for a bandit who trampled all laws and customs of conventional conduct. He gave them orders one instant and almost apologized for them in the next.

The matter of designating the camp site sounded almost as if they were prisoners, yet he had made no attempt to disarm them. His men were sullen and silent, even for bandits. But he had no reason to be hostile toward his guests, and, even if he had, why had he brought them to Khuruk, when he could have wiped them out up in the hills just as easily?

“Ali el Ghazi,” Afzal Khan suddenly repeated the name. “Wherefore Ghazi? What infidel didst thou slay to earn the name?”

“The Russian, Colonel Ivan Kurovitch.” O’Donnell spoke no lie there. As Ali el Ghazi, a Kurd, he was known as the slayer of Kurovitch; the duel had occurred in one of the myriad nameless skirmishes along the border.

Afzal Khan meditated this matter for a few minutes. The firelight cast part of his features in shadow, making his expression seem even more sinister than usual. He loomed in the firelit shadows like a somber monster weighing the doom of men. Then with a grunt he turned and strode away toward the sangar.

Night had fallen. Wind moaned among the crags. Cloud masses moved across the dark vault of the night, obscuring the stars which blinked here and there, were blotted out and then reappearing, like chill points of frosty silver. The Turkomans squatted silently about their tiny fires, casting furtive glances over their shoulders.

Men of the deserts, the brooding grimness of the dark mountains daunted them; the night pressing down in the bowl of the valley dwarfed them in its immensity. They shivered at the wailing of the wind, and peered fearfully, into the darkness, where, according to their superstitions, the ghosts of murdered men roamed ghoulishly. They stared bleakly at O’Donnell, in the grip of fear and paralyzing fatalism.

The grimness and desolation of the night had its effect on the American. A foreboding of disaster oppressed him. There was something about Afzal Khan he could not fathom—something unpredictable.

The man had lived too long outside the bounds of ordinary humanity to be judged by the standards of common men. In his present state of mind the bandit chief assumed monstrous proportions, like an ogre out of a fable.

O’Donnell shook himself angrily. Afzal Khan was only a man, who would die if bitten by lead or steel, like any other man. As for treachery, what would be the motive? Yet the foreboding remained.

“Tomorrow we will feast,” he told his men. “Afzal Khan has said it.”

They stared at him somberly, with the instincts of the black forests and the haunted steppes in their eyes which gleamed wolfishly in the firelight.

“The dead feast not,” muttered one of them.

“What talk is this?” rebuked O’Donnell. “We are living men, not dead.”

“We have not eaten salt with Afzal Khan,” replied the Turkoman. “We camp here in the open, hemmed in by his slayers on either hand. Aie, we are already dead men. We are sheep led to the butcher.”

O’Donnell stared hard at his men, startled at their voicing the vague fears that troubled him. There was no accusation of his leadership in their voices. They merely spoke their beliefs in a detached way that belied the fear in their eyes. They believed they were to die, and he was beginning to believe they were right. The fires were dying down, and there was no more fuel to build them up. Some of the men wrapped themselves in their cloaks and lay down on the hard ground. Others remained sitting cross-legged on their saddle cloths, their heads bent on their breasts.

O’Donnell rose and walked toward the first outcropping of the rocks, where he turned and stared back at the inclosure. The fires had died down there to a glow. No sound came from the sullen walls. A mental picture formed itself in his mind, resultant from his visit to the redoubt for water.

It was a bare wall inclosing a square space. At the northwest corner rose a tower. At the southwest corner there was a well. Once a tower had protected the well, but now it was fallen into ruins, so that only a hint of it remained. There was nothing else in the inclosure except a small stone hut with a thatched roof. What was in the hut he had no way of knowing. Afzal Khan had remarked that he slept alone in the tower. The chief did not trust his own men too far.

What was Afzal Khan’s game? He was not dealing straight with O’Donnell; that was obvious. Some of his evasions and pretenses were transparent; the man was not as clever as one might suppose; he was more like a bull that wins by ferocious charges.

But why should he practice deception? What had he to gain? O’Donnell had smelled meat cooking in the fortalice. There was food in the valley, then, but for some reason the Afghan had denied it. The Turkomans knew that; to them it logically suggested but one thing—he would not share the salt with men he intended to murder. But again, why?

“Ohai, Ali el Ghazi!”

At that hiss out of the darkness, O’Donnell wheeled, his big pistol jumping into his hand, his skin prickling. He strained his eyes, but saw nothing; heard only the muttering of the night wind.

“Who is it?” he demanded guardedly. “Who calls?”

“A friend! Hold your fire!”

O’Donnell saw a more solid shadow detach itself from the rocks and move toward him. With his thumb pressing back the fanged hammer of his pistol, he shoved the muzzle against the man’s belly and leaned forward to glare into the hairy face in the dim, uncertain starlight. Even so the darkness was so thick the fellow’s features were only a blur.

“Do you not know me?” whispered the man, and by his accent O’Donnell knew him for a Waziri. “I am Yar Muhammad!”

“Yar Muhammad!” Instantly the gun went out of sight and O’Donnell’s hand fell on the other’s bull-like shoulder. “What do you in this den of thieves?”

The man’s teeth glimmered in the tangle of his beard as he grinned. “Mashallah! Am I not a thief, El Shirkuh?” he asked, giving O’Donnell the name by which the American, in his rightful person, was known to the Moslems. “Hast thou forgotten the old days? Even now the British would hang me, if they could catch me. But no matter. I was one of those who watch the paths in the hills.

“An hour ago I was relieved, and when I returned to the sangar I heard men talking of the Turkomans who camped in the valley outside, and it was said their chief was the Kurd who slew the infidel Kurovitch. So I knew it was El Shirkuh playing with doom again. Art thou mad, sahib? Death spreads his wings above thee and all thy men. Afzal Khan plots that thou seest no other sunrise.”

“I was suspicious of him,” muttered the American. “In the matter of food—-”

“The hut in the inclosure is full of food. Why waste beef and bread on dead men? Food is scarce enough in these hills—and at dawn you die.”

“But why? We saved Afzal Khan’s life, and there is no feud—-”

“The Jhelum will flow backward when Afzal Khan spares a man because of gratitude,” muttered Yar Muhammad.

“But for what reason?”

“By Allah, sahib, are you blind? Reason? Are not fifty Turkish steeds reason enough? Are not fifty rifles with cartridges reason enough? In these hills firearms and cartridges are worth their weight in silver, and a man will murder his brother for a matchlock. Afzal Khan is a robber, and he covets what you possess.

“These weapons and these horses would lend him great strength. He is ambitious. He would draw to him many more men, make himself strong enough at last to dispute the rule of these hills with Orkhan Bahadur. Nay, he plots some day to take Shahrazar from the Turkoman as he in his turn took it from the Uzbeks. What is the goal of every bandit in these hills, rich or poor? Mashallah! The treasure of Khuwarezm!”

O’Donnell was silent, visualizing that accursed hoard as a monstrous loadstone drawing all the evil passions of men from near lands and far. Now it was but an empty shadow men coveted, but they could not know it, and its evil power was as great as ever. He felt an insane desire to laugh.

The wind moaned in the dark, and Yar Muhammad’s muttering voice merged eerily with it, unintelligible a yard away.

“Afzal Khan feels no obligation toward you, because you thought it was Ahmed Shah you were aiding. He did not attack you at the Pass because he knew you would slay many of his men, and he feared lest the horses take harm in the battle. Now he has you in a trap as he planned. Sixty men inside the sangar; a hundred more at the head of the valley. A short time before moonrise, the men among the spurs will creep down the valley and take position among these rocks. Then when the moon is well risen, so that a man may aim, they will rake you with rifle fire.”

“Most of the Turkomans will die in their sleep, and such as live and seek to flee in the other direction will be shot by the men in the inclosure. These sleep now, but sentries keep watch. I slipped out over the western side and have been lying here wondering how to approach your camp without being shot for a prowler.

“Afzal Khan has plotted well. He has you in the perfect trap, with the horses well out of the range of the bullets that will slay their riders.”

“So,” murmured O’Donnell. “And what is your plan?”

“Plan? Allah, when did I ever have a plan? Nay, that is for you! I know these hills, and I can shoot straight and strike a good blow.” His yard-long Khyber knife thrummed as he swung it through the air. “But I only follow where wiser men lead. I heard the men talk, and I came to warn you, because once you turned an Afridi blade from my breast, and again you broke the lock on the Peshawar jail where I lay moaning for the hills!”

O’Donnell did not express his gratitude; that was not necessary. But he was conscious of a warm glow toward the hairy ruffian. Man’s treachery is balanced by man’s loyalty, at least in the barbaric hills where civilized sophistry has not crept in with its cult of time-serving.

“Can you guide us through the mountains?” asked O’Donnell.

“Nay, sahib; the horses cannot follow these paths; and these booted Turks would die on foot.”

“It is nearly two hours yet until moonrise,” O’Donnell muttered. “To saddle horses now would be to betray us. Some of us might get away in the darkness, but—-”

He was thinking of the papers that were the price of his life; but it was not altogether that. Flight in the darkness would mean scattered forces, even though they cut their way out of the valley. Without his guidance the Turkomans would be hopelessly lost; such as were separated from the main command would perish miserably.

“Come with me,” he said at last, and hurried back to the men who lay about the charring embers.

At his whisper they rose like ghouls out of the blackness and clustered about him, muttering like suspicious dogs at the Waziri. O’Donnell could scarcely make out the hawklike faces that pressed close about him. All the stars were hidden by dank clouds. The fortalice was but a shapeless bulk in the darkness, and the flanking mountains were masses of solid blackness. The whining wind drowned voices a few yards away.

“Hearken and speak not,” O’Donnell ordered. “This is Yar Muhammad, a friend and a true man. We are betrayed. Afzal Khan is a dog, who will slay us for our horses. Nay, listen! In the sangar there is a thatched hut. I am going into the inclosure and fire that thatch. When you see the blaze, and hear my pistol speak, rush the wall. Some of you will die, but the surprise will be on our side. We must take the sangar and hold it against the men who will come down the valley at moonrise. It is a desperate plan, but the best that offers itself.”

“Bismillah!” they murmured softly, and he heard the rasp of blades clearing their scabbards.

“This is work indeed for cold steel,” he said. “You must rush the wall and swarm it while the Pathans are dazed with surprise. Send one man for the warriors at the horse pen. Be of good heart; the rest is on Allah’s lap.”

As he crept away in the darkness, with Yar Muhammad following him like a bent shadow, O’Donnell was aware that the attitude of the Turkomans had changed; they had wakened out of their fatalistic lethargy into fierce tension.

“If I fall,” O’Donnell murmured, “will you guide these men back to Shahrazar? Orkhan Bahadur will reward you.”

“Shaitan eat Orkhan Bahadur,” answered Yar Muhammad. “What care I for these Turki dogs? It is you, not they, for whom I risk my skin.”

O’Donnell had given the Waziri his rifle. They swung around the south side of the inclosure, almost crawling on their bellies. No sound came from the breastwork, no light showed. O’Donnell knew that they were invisible to whatever eyes were straining into the darkness along the wall. Circling wide, they approached the unguarded western wall.

“Afzal Khan sleeps in the tower,” muttered Yar Muhammad, his lips close to O’Donnell’s ear. “Sleeps or pretends to sleep. The men slumber beneath the eastern wall. All the sentries lurk on that side, trying to watch the Turkomans. They have allowed the fires to die, to lull suspicion.”

“Over the wall, then,” whispered O’Donnell, rising and gripping the coping. He glided over with no more noise than the wind in the dry tamarisk, and Yar Muhammad followed him as silently. He stood in the thicker shadow of the wall, placing everything in his mind before he moved.

The hut was before him, a blob of blackness. It looked eastward and was closer to the west wall than to the other. Near it a cluster of dying coals glowed redly. There was no light in the tower, in the northwest angle of the wall.

Bidding Yar Muhammad remain near the wall, O’Donnell stole toward the embers. When he reached them he could make out the forms of the men sleeping between the hut and the east wall. It was like these hardened killers to sleep at such a time. Why not? At the word of their master they would rise and slay. Until the time came it was good to sleep. O’Donnell himself had slept, and eaten, too, among the corpses of a battlefield.

Dim figures along the wall were sentinels. They did not turn; motionless as statues they leaned on the wall staring into the darkness out of which, in the hills, anything might come.

There was a half-burned faggot dying in the embers, one end a charring stump which glowed redly. O’Donnell reached out and secured it. Yar Muhammad, watching from the wall, shivered, though he knew what it was. It was as if a detached hand had appeared for an instant in the dim glow and then disappeared, and then a red point moved toward him.

“Allah!” swore the Waziri. “This blackness is that of Jehannum!”

“Softly!” O’Donnell whispered at him from the pit darkness. “Be ready; now is the beginning of happenings.”

The ember glowed and smoked as he blew cautiously upon it. A tiny tongue of flame grew, licking at the wood. “Commend thyself to Allah!” said O’Donnell, and whirling the brand in a flaming wheel about his head, he cast it into the thatch of the hut.

There was a tense instant in which a tongue of flame flickered and crackled, and then in one hungry combustion the dry stuff leaped ablaze, and the figures of men started out of blank blackness with startling clarity. The guards wheeled, their stupid astonishment etched in the glare, and men sat up in their cloaks on the ground, gaping bewilderedly.

And O’Donnell yelled like a hungry wolf and began jerking the trigger of his pistol.

A sentinel spun on his heel and crumpled, discharging his rifle wildly in the air. Others were howling and staggering like drunken men, reeling and falling in the lurid glare. Yar Muhammad was blazing away with O’Donnell’s rifle, shooting down his former companions as cheerfully as if they were ancient enemies.

A matter of seconds elapsed between the time the blaze sprang up and the time when the men were scurrying about wildly, etched in the merciless light and unable to see the two men who crouched in the shadow of the far wall, raining them with lead. But in that scant instant there came another sound—a swift thudding of feet, the daunting sound of men rushing through the darkness in desperate haste and desperate silence.

Some of the Pathans heard it and turned to glare into the night. The fire behind them rendered the outer darkness more impenetrable. They could not see the death that was racing, fleetly toward them, until the charge reached the wall.

Then a yell of terror went up as the men along the wall caught a glimpse of glittering eyes and flickering steel rushing out of the blackness. They fired one wild, ragged volley, and then the Turkomans surged up over the wall in an irresistible wave and were slashing and hacking like madmen among the defenders.

Scarcely wakened, demoralized by the surprise, and by the bullets that cut them down from behind, the Pathans were beaten almost before the fight began. Some of them fled over the wall without any attempt at defense, but some fought, snarling and stabbing like wolves. The blazing thatch etched the scene in a lurid glare. Kalpaks mingled with turbans, and steel flickered over the seething mob. Yataghans grated against tulwars, and blood spurted.

His pistol empty, O’Donnell ran toward the tower. He had momentarily expected Afzal Khan to appear. But in such moments it is impossible to retain a proper estimate of time. A minute may seem like an hour, an hour like a minute. In reality, the Afghan chief came storming out of the tower just as the Turkomans came surging over the wall. Perhaps he had really been asleep, or perhaps caution kept him from rushing out sooner. Gunfire might mean rebellion against his authority.

At any rate he came roaring like a wounded bull, a rifle in his hands. O’Donnell rushed toward him, but the Afghan glared beyond him to where his swordsmen were falling like wheat under the blades of the maddened Turkomans. He saw the fight was already lost, as far as the men in the inclosure were concerned, and he sprang for the nearest wall.

O’Donnell raced to pull him down, but Afzal Khan, wheeling, fired from the hip. The American felt a heavy blow in his belly, and then he was down on the ground, with all the breath gone from him. Afzal Khan yelled in triumph, brandished his rifle, and was gone over the wall, heedless of the vengeful bullet Yar Muhammad sped after him.

The Waziri had followed O’Donnell across the inclosure and now he knelt beside him, yammering as he fumbled to find the American’s wound.

“Aie!” he bawled. “He is slain! My friend and brother! Where will his like be found again? Slain by the bullet of a hillman! Aie! Aie! Aie!”

“Cease thy bellowing, thou great ox,” gasped O’Donnell, sitting up and shaking off the frantic hands. “I am unhurt.”

Yar Muhammad yelled with surprise and relief. “But the bullet, brother? He fired at point-blank range!”

“It hit my belt buckle,” grunted O’Donnell, feeling the heavy gold buckle, which was bent and dented. “By Allah, the slug drove it into my belly. It was like being hit with a sledge hammer. Where is Afzal Khan?”

“Fled away in the darkness.”

O’Donnell rose and turned his attention to the fighting. It was practically over. The remnants of the Pathans were fleeing over the wall, harried by the triumphant Turkomans, who in victory were no more merciful than the average Oriental. The sangar looked like a shambles.

The hut still blazed brightly, and O’Donnell knew that the contents had been ignited. What had been an advantage was now a danger, for the men at the head of the valley would be coming at full run, and in the light of the fire they could pick off the Turkomans from the darkness. He ran forward shouting orders, and setting an example of action.

Men began filling vessels—cooking pots, gourds, even kalpaks from the well and casting the water on the fire. O’Donnell burst in the door and began to drag out the contents of the huts, foods mostly, some of it brightly ablaze, to be doused.

Working as only men in danger of death can work, they extinguished the flame and darkness fell again over the fortress. But over the eastern crags a faint glow announced the rising of the moon through the breaking clouds.

Then followed a tense period of waiting, in which the Turkomans hugged their rifles and crouched along the wall, staring into the darkness as the Pathans had done only a short time before. Seven of them had been killed in the fighting and lay with the wounded beside the well. The bodies of the slain Pathans had been unceremoniously heaved over the wall.

The men at the valley head could not have been on their way down the valley when the fighting broke out, and they must have hesitated before starting, uncertain as to what the racket meant. But they were on their way at last, and Afzal Khan was trying to establish a contact with them.

The wind brought snatches of shouts down the valley, and a rattle of shots that hinted at hysteria. These were followed by a furious bellowing which indicated that Afzal Khan’s demoralized warriors had nearly shot their chief in the dark. The moon broke through the clouds and disclosed a straggling, mob of men gesticulating wildly this side of the rocks to the east.

O’Donnell even made out Afzal Khan’s bulk and, snatching a rifle from a warrior’s hand, tried a long shot. He missed in the uncertain light, but his warriors poured a blast of lead into the thick of their enemies which accounted for a man or so and sent the others leaping for cover. From the reeflike rocks they began firing at the wall, knocking off chips of stone but otherwise doing no damage.

With his enemies definitely located, O’Donnell felt more at ease. Taking a torch he went to the tower, with Yar Muhammad hanging at his heels like a faithful ghoul. In the tower were heaped odds and ends of plunder—saddles, bridles, garments, blankets, food, weapons—but O’Donnell did not find what he sought, though he tore the place to pieces. Yar Muhammad squatted in the doorway, with his rifle across his knees, and watched him, it never occurring to the Waziri to inquire what his friend was searching for.

At length O’Donnell paused, sweating from the vigor of his efforts—for he had concentrated much exertion in a few minutes—and swore.

“Where does the dog keep those papers?”

“The papers he took from Ahmed Shah?” inquired Yar Muhammad. “Those he always carries in his girdle. He cannot read them, but he believes they are valuable. Men say Ahmed Shah had them from a Feringi who died.”

Dawn was lifting over the valley of Khuruk. The sun that was not yet visible above the rim of the hills turned the white peaks to pulsing fire. But down in the valley there was none who found time to wonder at the changeless miracle of the mountain dawn. The cliffs rang with the flat echoes of rifle shots, and wisps of smoke drifted bluely into the air. Lead spanged on stone and whined venomously off into space, or thudded sickeningly into quivering flesh. Men howled blasphemously and fouled the morning with their frantic curses.

O’Donnell crouched at a loophole, staring at the rocks whence came puffs of white smoke and singing harbingers of death. His rifle barrel was hot to his hand, and a dozen yards from the wall lay a huddle of white-clad figures.

Since the first hint of light the wolves of Afzal Khan had poured lead into the fortalice from the reeflike ledge that broke the valley floor. Three times they had broken cover and charged, only to fall back beneath the merciless fire that raked them. Hopelessly outnumbered, the advantage of weapons and position counted heavily for the Turkomans.

O’Donnell had stationed five of the best marksmen in the tower and the rest held the walls. To reach the inclosure meant charging across several hundred yards of open space, devoid of cover. All the outlaws were still among the rocks east of the sangar, where, indeed, the broken ledge offered the only cover within rifle range of the redoubt.

The Pathans had suffered savagely in the charges, and they had had the worst of the long-range exchanges, both their marksmanship and their weapons being inferior to the Turkomans’. But some of their bullets did find their way through the loopholes. A few yards from O’Donnell a kaftaned rider lay in a grotesque huddle, his feet turned so the growing light glinted on his silver boot heels, his head a smear of blood and brains.

Another lay sprawled near the charred hut, his ghastly face frozen in a grin of agony as he chewed spasmodically on a bullet. He had been shot in the belly and was taking a long time in dying, but not a whimper escaped his livid lips.

A fellow with a bullet hole in his forearm was making more racket; his curses, as a comrade probed for the slug with a dagger point, would have curdled the blood of a devil.

O’Donnell glanced up at the tower, whence wisps of smoke drifting told him that his five snipers were alert. Their range was greater than that of the men at the wall, and they did more damage proportionately and were better protected. Again and again they had broken up attempts to get at the horses in the stone pen. This pen was nearer the inclosure than it was to the rocks, and crumpled shapes on the ground showed of vain attempts to reach it.

But O’Donnell shook his head. They had salvaged a large quantity of food from the burning hut; there was a well of good water; they had better weapons and more ammunition than the men outside. But a long siege meant annihilation.

One of the men wounded in the night fighting had died. There remained alive forty-one men of the fifty with which he had left Shahrazar. One of these was dying, and half a dozen were wounded—one probably fatally. There were at least a hundred and fifty men outside.

Afzal Khan could not storm the walls yet. But under the constant toll of the bullets, the small force of the defenders would melt away. If any of them lived and escaped, O’Donnell knew it could be only by a swift, bold stroke. But he had no plan at all.

The firing from the valley ceased suddenly, and a white turban cloth was waved above the rock of a rifle muzzle.

“Ohai, Ali el Ghazi!” came a hail in a bull’s roar that could only have issued from Afzal Khan.

Yar Muhammad, squatting beside O’Donnell sneered. “A trick! Keep thy head below the parapet, sahib. Trust Afzal Khan when wolves knock out their own teeth.”

“Hold your fire, Ali el Ghazi!” boomed the distant voice. “I would parley with you!”

“Show yourself!” O’Donnell yelled back.

And without hesitation a huge bulk loomed up among the rocks. Whatever his own perfidy, Afzal Khan trusted the honor of the man he thought a Kurd. He lifted his hands to show they were empty.

“Advance, alone!” yelled O’Donnell, straining to make himself heard.

Someone thrust the butt of a rifle into a crevice of the rocks so it stood muzzle upward, with the white cloth blowing out in the morning breeze, and Afzal Khan came striding over the stones with the arrogance of a sultan. Behind him turbans were poked up above the boulders.

O’Donnell halted him within good earshot, and instantly he was covered by a score of rifles. Afzal Khan did not seem to be disturbed by that, or by the blood lust in the dark hawklike faces glaring along the barrels. Then O’Donnell rose into view, and the two leaders faced one another in the full dawn.

O’Donnell expected accusations of treachery—for, after all, he had struck the first blow—but Afzal Khan was too brutally candid for such hypocrisy.

“I have you in a vise, Ali el Ghazi,” he announced without preamble. “But for that Waziri dog who crouches behind you, I would have cut your throat at moonrise last night. You are all dead men, but siege work grows tiresome, and I am willing to forgo half my advantage. I am generous. As reward of victory I demand either your guns or your horses. Your horses I have already, but you shall have them back, if you wish. Throw down your weapons and you may ride out of Khuruk. Or, if you wish, I will keep the horses, and you may march out on foot with your rifles. What is your answer?”

O’Donnell spat toward him, with a typically Kurdish gesture. “Are we fools, to be hoodwinked by a dog with scarlet whiskers?” he snarled. “When Afzal Khan keeps his sworn word, the Indus will flow backward. Shall we ride out, unarmed, for you to cut us down in the passes, or shall we march forth on foot, for you to shoot us from ambush in the hills?

“You lie when you say you have our horses. Ten of your men have died trying to take them for you. You lie when you say you have us in the vise. It is you who are in the vise! You have neither food nor water; there is no other well in the valley but this. You have few cartridges, because most of your ammunition is stored in the tower, and we hold that.”

The fury in Afzal Khan’s countenance told O’Donnell that he had scored with that shot.

“If you had us helpless you would not be offering terms,” O’Donnell sneered. “You would be cutting our throats, instead of trying to gull us into the open.”

“Sons of sixty dogs!” swore Afzal Khan, plucking at his beard. “I will flay you all alive! I will keep you hemmed here until you die!”

“If we cannot leave the fortress, you cannot enter it,” O’Donnell retorted. “Moreover you have drawn all your men but a handful from the passes, and the Khurukzai will steal upon you and cut off your heads. They are waiting, up in the hills.”

Afzal Khan’s involuntarily wry face told O’Donnell that the Afghan’s plight was more desperate than he had hoped.

“It is a deadlock, Afzal Khan,” said O’Donnell suddenly.

“There is but one way to break it.” He lifted his voice, seeing that the Pathans under the protection of the truce were leaving their coverts and drawing within earshot. “Meet me there in the open space, man to man, and decide the feud between us two, with cold steel. If I win, we ride out of Khuruk unmolested. If you win, my warriors are at your mercy.”

“The mercy of a wolf!” muttered Yar Muhammad.

O’Donnell did not reply. It was a desperate chance, but the only one. Afzal Khan hesitated and cast a searching glance at his men; that scowling hairy horde was muttering among itself. The warriors seemed ill-content, and they stared meaningly at their leader.

The inference was plain; they were weary of the fighting at which they were at a disadvantage, and they wished Afzal Khan to accept O’Donnell’s challenge. They feared a return of the Khurukzai might catch them in the open with empty cartridge pouches. After all, if their chief lost to the Kurd, they would only lose the loot they had expected to win. Afzal Khan understood this attitude, and his beard bristled to the upsurging of his ready passion.

“Agreed!” he roared, tearing out his tulwar and throwing away the scabbard. He made the bright broad steel thrum about his head. “Come over the wall and die, thou slayer of infidels!”

“Hold your men where they are!” O’Donnell ordered and vaulted the parapet.

At a bellowed order the Pathans had halted, and the wall was lined with kalpaks as the Turkomans watched tensely, muzzles turned upward but fingers still crooked on the triggers: Yar Muhammad followed O’Donnell over the wall, but did not advance from it; he crouched against it like a bearded ghoul, fingering his knife.

O’Donnell wasted no time. Scimitar in one hand and kindhjal in the other, he ran lightly toward the burly figure advancing to meet him. O’Donnell was slightly above medium height, but Afzal Khan towered half a head above him. The Afghan’s bull-like shoulders and muscular bulk contrasted with the rangy figure of the false Kurd; but O’Donnell’s sinews were like steel wires. His Arab scimitar, though neither so broad nor so heavy as the tulwar, was fully as long, and the blade was of unbreakable Damascus steel.

The men seemed scarcely within arm’s reach when the fight opened with a dazzling crackle and flash of steel. Blow followed blow so swiftly that the men watching, trained to arms since birth, could scarcely follow the strokes. Afzal Khan roared, his eyes blazing, his beard bristling, and wielding the heavy tulwar as one might wield a camel wand, he flailed away in a frenzy .

But always the scimitar flickered before him, turning the furious blows, or the slim figure of the false Kurd avoided death by the slightest margins, with supple twists and swayings. The scimitar bent beneath the weight of the tulwar, but it did not break; like a serpent’s tongue it always snapped straight again, and like a serpent’s tongue it flickered at Afzal Khan’s breast, his throat, his groin, a constant threat of death that reddened the Afghan’s eyes with a tinge akin to madness.

Afzal Khan was a famed swordsman, and his sheer brute strength was more than a man’s. But O’Donnell’s balance and economy of motion was a marvel to witness. He never set a foot wrong or made a false motion; he was always poised, always a threat, even in retreat, beaten backward by the bull-like rushes of the Afghan. Blood trickled down his face where a furious stroke, beating down his blade, had bitten through his silk turban and into the scalp, but the flame in his blue eyes never altered.

Afzal Khan was bleeding, too, O’Donnell’s point, barely missing his jugular, had plowed through his beard and along his jaw. Blood dripping from his beard made his aspect more fearsome than ever. He roared and flailed, until it seemed that the fury of his onslaught would overbalance O’Donnell’s perfect mastery of himself and his blade.

Few noticed, however, that O’Donnell had been working his way in closer and closer under the sweep of the tulwar. Now he caught a furious swipe near the hilt and the kindhjal in his left hand licked in and out. Afzal Khan’s bellow caught in a gasp. There was but that fleeting instant of contact, so brief it was like blur of movement, and then O’Donnell, at arm’s length again, was slashing and parrying, but now there was a thread of crimson on the narrow kindhjal blade, and blood was seeping in a steady stream through Afzal Khan’s broad girdle.

There was the pain and desperation of the damned in the Afghan’s eyes, in his roaring voice. He began to weave drunkenly, but he attacked more madly than ever, like a man fighting against time.

His strokes ribboned the air with bright steel and thrummed past O’Donnell’s ears like a wind of death, until the tulwar rang full against the scimitar’s guard with hurricane force and O’Donnell went to his knee under the impact. “Kurdish dog!” It was a gasp of frenzied triumph. Up flashed the tulwar and the watching hordes gave tongue. But again the kindhjal licked out like a serpent’s tongue—outward and upward.

The stroke was meant for the Afghan’s groin, but a shift of his legs at the instant caused the keen blade to plow through his thigh instead, slicing veins and tendons. He lurched sidewise, throwing out his arm to balance himself. And even before men knew whether he would fall or not, O’Donnell was on his feet and slashed with the scimitar at his head.

Afzal Khan fell as a tree falls, blood gushing from his head. Even so, the terrible vitality of the man clung to life and hate. The tulwar fell from his hand, but, catching himself on his knees, he plucked a knife from his girdle; his hand went back for the throw—then the knife slipped from his nerveless fingers and he crumpled to the earth and lay still.

There was silence, broken by a strident yell from the Turkomans. O’Donnell sheathed his scimitar, sprang swiftly to the fallen giant and thrust a hand into his blood-soaked girdle. His fingers closed on what he had hoped to find, and he drew forth an oilskin-bound packet of papers. A low cry of satisfaction escaped his lips.

In the tense excitement of the fight, neither he nor the Turkomans had noticed that the Pathans had drawn nearer and nearer, until they stood in a ragged semicircle only a few yards away. Now, as O’Donnell stood staring at the packet, a hairy ruffian ran at his back, knife lifted.

A frantic yell from Yar Muhammad warned O’Donnell. There was no time to turn; sensing rather than seeing his assailant, the American ducked deeply and the knife flashed past his ear, the muscular forearm falling on his shoulder with such force that again he was knocked to his knees.

Before the man could strike again Yar Muhammad’s yard-long knife was driven into his breast with such fury that the point sprang out between his shoulder blades. Wrenching his blade free as the wretch fell, the Waziri grabbed a handful of O’Donnell’s garments and began to drag him toward the wall, yelling like a madman.

It had all happened in a dizzying instant, the charge of the Pathan, Yar Muhammad’s leap and retreat. The other Pathans rushed in, howling like wolves, and the Waziri’s blade made a fan of steel about him and O’Donnell. Blades were flashing on all sides; O’Donnell was cursing like a madman as he strove to halt Yar Muhammad’s headlong progress long enough to get to his feet, which was impossible at the rate he was being yanked along.

All he could see was hairy legs, and all he could hear was a devil’s din of yells and clanging knives. He hewed sidewise at the legs and men howled, and then there was a deafening reverberation, and a blast of lead at close range smote the attackers and mowed them down like wheat. The Turkomans had woken up and gone into action.

Yar Muhammad was berserk. With his knife dripping red and his eyes blazing madly he swarmed over the wall and down on the other side, all asprawl, lugging O’Donnell like a sack of grain, and still unaware that his friend was not fatally wounded.

The Pathans were at his heels, not to be halted so easily this time. The Turkomans fired point-blank into their faces, but they came on, snarling, snatching at the rifle barrels poked over the wall, stabbing upward.

Yar Muhammad, heedless of the battle raging along the wall, was crouching over O’Donnell, mouthing, so crazy with blood lust and fighting frenzy that he was hardly aware of what he was doing, tearing at O’Donnell’s clothing in his efforts to discover the wound he was convinced his friend had received.

He could hardly be convinced otherwise by O’Donnell’s lurid blasphemy, and then he nearly strangled the American in a frantic embrace of relief and joy. O’Donnell threw him off and leaped to the wall, where the situation was getting desperate for the Turkomans. The Pathans, fighting without leadership, were massed in the middle of the east wall, and the men in the tower were pouring a devastating fire into them, but the havoc was being wreaked in the rear of the horde. The men in the tower feared to shoot at the attackers along the wall for fear of hitting their own comrades.

As O’Donnell reached the wall, the Turkoman nearest him thrust his muzzle into a snarling, bearded face and pulled the trigger, blasting the hillman’s head into a red ruin. Then before he could fire again a knife licked over the wall and disemboweled him. O’Donnell caught the rifle as it fell, smashed the butt down on the head of a hillman climbing over the parapet, and left him hanging dead across the wall.

It was all confusion and smoke and spurting blood and insanity. No time to look right or left to see if the Turkomans still held the wall on either hand. He had his hands full with the snarling bestial faces which rose like a wave before him. Crouching on the firing step, he drove the blood-clotted butt into these wolfish faces until a rabid-eyed giant grappled him and bore him back and over.

They struck the ground on the inside, and O’Donnell’s head hit a fallen gun stock with a stunning crack. In the moment that his brain swam dizzily the Pathan heaved him underneath, yelled stridently and lifted a knife—then the straining body went suddenly limp, and O’Donnell’s face was spattered with blood and brains, as Yar Muhammad split the man’s head to the teeth with his Khyber knife.

The Waziri pulled the corpse off and O’Donnell staggered up, slightly sick, and presenting a ghastly spectacle with his red-dabbled face, hands, and garments. The firing, which had lulled while the fighting locked along the wall, now began again. The disorganized Pathans were falling back, were slinking away, breaking and fleeing toward the rocks.

The Turkomans had held the wall, but O’Donnell swore sickly as he saw the gaps in their ranks. One lay dead in a huddle of dead Pathans outside the wall, and five more hung motionless across the wall, or were sprawled on the ground. With these latter were the corpses of four Pathans, to show how desperate the brief fight had been. The number of the dead outside was appalling.

O’Donnell shook his dizzy head, shuddering slightly at the thought of how close to destruction his band had been; if the hillmen had had a leader, had kept their wits about them enough to have divided forces and attacked in several places at once—but it takes a keen mind to think in the madness of such a battle. It had been blind, bloody, and furious, and the random-cast dice of fate had decided for the smaller horde.

The Pathans had taken to the rocks again and were firing in a half-hearted manner. Sounds of loud argument drifted down the wind. He set about dressing the wounded as best he could, and while he was so employed, the Pathans tried to get at the horses again. But the effort was without enthusiasm, and a fusillade from the tower drove them back.

As quickly as he could, O’Donnell retired to a corner of the wall and investigated the oilskin-wrapped packet he had taken from Afzal Khan. It was a letter, several sheets of high-grade paper covered with a fine scrawl. The writing was Russian, notUrdu, and there were English margin notes in a different hand. These notes made clear points suggested in the letter, and O’Donnell’s face grew grim as he read.

How the unknown English secret-service man who had added those notes had got possession of the letter there was no way of knowing; but it had been intended for the man called Suleiman Pasha, and it revealed what O’Donnell had suspected—a plot within a plot; a red and sinister conspiracy concealing itself in a guise of international policy.

Suleiman Pasha was not only a foreign spy; he was a traitor to the men he served. And the tentacles of the plot which revolved about him stretched incredibly southward into high places. O’Donnell swore softly as he read there the names of men trusted by the government they pretended to serve. And slowly a realization crystallized—this letter must never reach Suleiman Pasha. Somehow, in some way, he, Kirby O’Donnell, must carry on the work of that unknown Englishman who had died with his task uncompleted. That letter must go southward, to lay bare black treachery spawning under the heedless feet of government. He hastily concealed the packet as the Waziri approached.

Yar Muhammad grinned. He had lost a tooth, and his black beard was streaked and clotted with blood which did not make him look any less savage.

“The dogs wrangle with one another,” he said, “It is always thus; only the hand of Afzal Khan kept them together. Now men who followed him will refuse to follow one of their own number. They fear the Khurukzai. We also have reason to beware of them. They will be waiting in the hills beyond the Pass of Akbar.”