Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

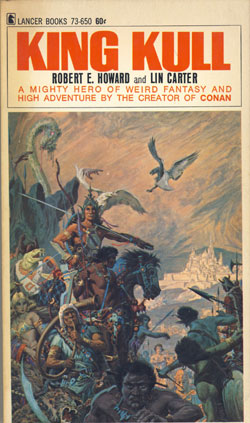

Published in King Kull, 1967.

| 1. “Valusia Plots Behind Closed Doors” 2. Mystery 3. The Sign of the Seal |

4. “Here I Stand at Bay!” 5. The Battle of the Stair |

A sinister quiet lay like a shroud over the ancient city of Valusia. The heat waves danced from roof to shining roof and shimmered against the smooth marble walls. The purple towers and golden spires were softened in the faint haze. No ringing hoofs on the wide paved streets broke the drowsy silence, and the few pedestrians who appeared did what they had to do hastily and vanished indoors again. The city seemed like a realm of ghosts.

Kull, king of Valusia, drew aside the filmy curtains and gazed over the golden window sill, out over the court with sparkling fountains and trim hedges and pruned trees, over the high wall and at the blank windows of houses which met his glance.

“All Valusia plots behind closed doors, Brule,” he grunted.

His companion, a dark-faced, powerful warrior of medium height, grinned hardly. “You are too suspicious, Kull. The heat drives most of them indoors.”

“But they plot,” reiterated Kull. He was a tall, broad-shouldered barbarian, with the true fighting build: wide shoulders, mighty chest, and lean flanks. Under heavy black brows his cold gray eyes brooded. His features betrayed his birthplace, for Kull the usurper was an Atlantean.

“True, they plot. When did the people ever fail to plot, no matter who held the throne? And they might be excused now, Kull.”

“Aye,” the giant’s brow clouded, “I am an alien. The first barbarian to press the Valusian throne since the beginning of time. When I was a commander of her forces they overlooked the accident of my birth. But now they hurl it into my teeth—by looks and thoughts, at least.”

“What do you care? I am an alien also. Aliens rule Valusia now, since the people have grown too weak and degenerate to rule themselves. An Atlantean sits on her throne, backed by all the Picts, the empire’s most ancient and powerful allies; her court is filled with foreigners; her armies with barbarian mercenaries; and the Red Slayers—well, they are at least Valusians, but they are men of the mountains who look upon themselves as a different race.”

Kull shrugged his shoulders restlessly.

“I know what the people think, and with what aversion and anger the powerful old Valusian families must look on the state of affairs. But what would you have? The empire was worse under Borna, a native Valusian and a direct heir of the old dynasty, than it has been under me. This is the price a nation must pay for decaying: the strong young people come in and take possession, one way or another. I have at least rebuilt the armies, organized the mercenaries and restored Valusia to a measure of her former international greatness. Surely it is better to have one barbarian on the throne holding the crumbling bands together, than to have a hundred thousand riding red-handed through the city streets. Which is what would have happened by now, had it been left to King Borna. The kingdom was splitting under his feet, invasion threatened on all sides, the heathen Grondarians were ready to launch a raid of appalling magnitude—

“Well, I killed Borna with my bare hands that wild night when I rode at the head of the rebels. That bit of ruthlessness won me some enemies, but within six months I had put down anarchy and all counter-rebellions, had welded the nation back into one piece, had broken the back of the Triple Federation, and crushed the power of the Grondarians. Now Valusia dozes in peace and quiet, and between naps plots my overthrow. There has been no famine since my reign, the storehouses are bulging with grain, the trading ships ride heavy with cargo, the merchants’ purses are full, the people are fat-bellied—but still they murmur and curse and spit on my shadow. What do they want?”

The Pict grinned savagely and with bitter mirth.

“Another Borna! A red-handed tyrant! Forget their ingratitude. You did not seize the kingdom for their sakes, nor do you hold it for their benefit. Well, you have accomplished a lifelong ambition, and you are firmly seated on the throne. Let them murmur and plot. You are king.”

Kull nodded grimly. “I am king of this purple kingdom! And until my breath stops and my ghost goes down the long shadow road, I will be king. What now?”

A slave bowed deeply, “Nalissa, daughter of the great house of bora Ballin, desires audience, most high majesty.”

A shadow crossed the king’s brow. “More supplication in regard to her damnable love affair,” he sighed to Brule. “Mayhap you’d better go.” To the slave, “Let her enter the presence.”

Kull sat in a chair padded with velvet and gazed at Nalissa. She was only some nineteen years of age; and clad in the costly but scanty fashion of Valusian noble ladies, she presented a ravishing picture, the beauty of which even the barbarian king could appreciate. Her skin was a marvelous white, due partly to many baths in milk and wine, but mainly to a heritage of loveliness. Her cheeks were tinted naturally with a delicate pink, and her lips were full and red. Under delicate black brows brooded a pair of deep soft eyes, dark as mystery, and the whole picture was set off by a mass of curly black hair which was partly confined by slim golden band.

Nalissa knelt at the feet of the king, and clasping his sword-hardened fingers in her soft slim hands, she looked up into his eyes; her own eyes luminous and pensive with appeal. Of all the people in the kingdom, Kull preferred not to look into the eyes of Nalissa. He saw there at times a depth of allure and mystery. She knew something of her powers, the spoiled and pampered child of aristocracy, but her full powers she little guessed because of her youth. But Kull, who was wise in the ways of men and women, realized with some uneasiness that with maturity Nalissa was bound to become a terrific power in the court and in the land, either for good or bad.

“But your majesty,” she was wailing now, like a child begging for a toy, “please let me marry Dalgar of Farsun. He has become a Valusian citizen, he is high in favor at court, as you yourself say. Why—”

“I have told you,” said the king with patience, “it is nothing to me whether you marry Dalgar, Brule, or the devil! But your father does not wish you to marry this Farsunian adventurer and—”

“But you can make him let me!” she cried.

“The house of bora Ballin I number among my staunchest supporters,” answered the Atlantean. “And Murom bora Ballin, your father, among my closest friends. When I was a friendless gladiator, he befriended me. He lent me money when I was a common soldier, and he espoused my cause when I struck for the throne. Not to save this right hand of mine would I force him into an action to which he is so violently opposed, or interfere in his family affairs.”

Nalissa had not yet learned that some men cannot be moved by feminine wiles. She pleaded, coaxed, and pouted. She kissed Kull’s hands, wept on his breast, perched on his knee and argued, all much to his embarrassment, but to no avail. Kull was sincerely sympathetic, but adamant. To all her appeals and blandishments he had one answer: that it was none of his business, that her father knew better what she needed, and that he, Kull, was not going to interfere.

At last Nalissa gave up and left the presence with bowed head and dragging steps. As she emerged from the royal chamber, she met her father coming in. Murom bora Ballin, guessing his daughter’s purpose in visiting the king, said nothing to her, but the look he gave her spoke eloquently of punishment to come.

The girl climbed miserably into her sedan chair, feeling as if her sorrow was too heavy a load for any one girl to bear. Then her inner nature asserted itself. Her dark eyes smoldered with rebellion, and she spoke a few quick words to the slaves who carried her chair.

Count Murom stood before his king meanwhile, and his features were frozen into a mask of formal deference. Kull noted that expression, and it hurt him. Formality existed between himself and all his subjects and allies except the Pict, Brule; and the ambassador, Ka-nu; but this studied formality was a new thing in Count Murom, and Kull guessed at the reason.

“Your daughter was here, Count,” he said abruptly.

“Yes, your majesty,” the tone was impassive and respectful.

“You probably know why. She wants to marry Dalgar of Farsun.”

The count made a stately inclination of his head.

“If your majesty so wishes, he has but to say the word.” His features froze into harder lines.

Kull, stung, rose and strode across the chamber to the window, where once again he gazed out at the drowsing city. Without turning, he said, “Not for half my kingdom would I interfere with your family affairs, nor force you into a course unpleasant to you.”

The count was at his side in an instant, his formality vanished, his fine eyes eloquent. “Your majesty, I have wronged you in my thoughts—I should have known—” He made as if to kneel, but Kull restrained him.

The king grinned. “Be at ease, Count. Your private affairs are your own. I cannot help you, but you can help me. There is conspiracy in the air; I smell danger as in my early youth I sensed the nearness of a tiger in the jungle or a serpent in the high grass.”

“My spies have been combing the city, your majesty,” said the count, his eyes kindling at the prospect of action. “The people murmur as they will murmur under any ruler—but I have recently come from Ka-nu at the consulate, and he told me to warn you that outside influence and foreign money were at work. He said he knew nothing definite, but his Picts wormed some information from a drunken servant of the Verulian ambassador—vague hints at some coup that government is planning.”

Kull grunted. “Verulian trickery is a byword. But Gen Dala, the Verulian ambassador, is the soul of honor.”

“So much better a figurehead. If he knows nothing of what his nation plans, so much the better will he serve as a mask for their doings.”

“But what would Verulia gain?” asked Kull.

“Gomlah, a distant cousin of King Gorna, took refuge there when you overthrew the old dynasty. With you slain, Valusia would fall to pieces. Her armies would become disorganized, all her allies except the Picts would desert her, the mercenaries whom only you can control would turn against her, and she would be an easy prey for the first powerful nation who might move against her. Then, with Gomlah as an excuse for invasion, as a puppet on Valusia’s throne—”

“I see,” grunted Kull. “I am better at battle than in council, but I see. So—the first step must be my removal, eh?”

“Yes, your majesty.”

Kull smiled and flexed his mighty arms. “After all, this ruling grows dull at times.” His fingers caressed the hilt of the great sword which he wore at all times.

“Tu, chief councilor to the king, and Dondal, his nephew,” sang out a slave, and two men entered the presence.

Tu, chief councilor, was a portly man of medium height and late middle life, who looked more like a merchant than a councilor. His hair was thin, his face lined, and on his brow rested a look of perpetual suspicion. Tu’s years and honors rested heavily on him. Originally of plebian birth, he had won his way by sheer power of craft and intrigue. He had seen three kings come and go before Kull, and the strain told on him.

His nephew Dondal was a slim, foppish youth with keen dark eyes and a pleasant smile. His chief virtue lay in the fact that he kept a discreet tongue in his head and never repeated what he heard at court. For this reason he was admitted into places not even warranted by his close kinship to Tu.

“Just a small matter of state, your majesty,” said Tu. “This permit for a new harbor on the western coast. Will your majesty sign?”

Kull signed his name; Tu drew from inside his bosom a signet ring attached to a small chain which he wore around his neck, and affixed the seal. This ring was the royal signature, in effect. No other ring in the world was exactly like it, and Tu wore it about his neck, waking or sleeping. Outside those in the royal chamber at the moment, not four men in the world knew where the ring was kept.

The quiet of the day had merged almost imperceptibly into the quiet of night. The moon had not yet risen, and the small silver stars gave little light, as if their radiance was strangled by the heat which still rose from the earth.

Along a deserted street a single horse’s hoofs clanged hollowly. If eyes watched from the blank windows, they gave no sign that betrayed that anyone knew Dalgar of Farsun was riding through the night and the silence.

The young Farsunian was fully armed, his lithe athletic body was completely encased in light armor, and a morion was on his head. He looked capable of handling the long, slim jewel-hilted sword at his side, and the scarf which crossed his steel-clad breast, with its red rose, detracted nothing from the picture of manhood he presented.

Now as he rode he glanced at a crumpled note in his hand, which, half unfolded, disclosed the following message in the characters of Valusia; “At midnight, my beloved, in the Accursed Gardens beyond the walls. We will fly together.”

A dramatic note; Dalgar’s handsome lips curved slightly as he read. Well, a little melodrama was pardonable in a young girl, and the youth enjoyed a touch himself. A thrill of ecstasy shook him at the thought of that rendezvous. By dawn he would be far across the Verulian border with his bride-to-be; then let Count Murom bora Ballin rave; let the whole Valusian army follow their tracks. With that much start, he and Nalissa would be in safety. He felt high and romantic; his heart swelled with the foolish heroics of youth. It was hours until midnight, but—he nudged his horse with an armored heel and turned aside to take a shortcut through some dark narrow streets.

“Oh, silver moon and a silver breast—” he hummed under his breath the flaming love songs of the mad, dead poet Ridondo; then his horse snorted and shied. In the shadow of a squalid doorway, a dark bulk moved and groaned.

Drawing his sword, Dalgar slipped from the saddle and bent over he who groaned.

Bending very close, he made out the form of a man. He dragged the body into a comparatively lighter area, noting that he was still breathing. Something warm and sticky adhered to his hand.

The man was portly and apparently old, since his hair was sparse and his beard shot with white. He was clad in the rags of a beggar, but even in the darkness Dalgar could tell that his hands were soft and white under their grime. A nasty gash on the side of his head seeped blood, and his eyes were closed. He groaned from time to time.

Dalgar tore a piece from his sash to staunch the wound, and in so doing, a ring on his finger became entangled in the unkempt beard. He jerked impatiently—the beard came away entirely, disclosing the smooth-shaven, deeply lined face of a man in late middle life. Dalgar cried out and recoiled. He bounded to his feet, bewildered and shocked. A moment he stood, staring down at the groaning man; then the quick rattle of hoofs on a parallel street recalled him to life.

He ran down a side alley and accosted the rider. This man pulled up with a quick motion, reaching for his sword as he did so. The steel-shod hoofs of his steed struck fire from the flagstones as the horse set back on his haunches.

“What now? Oh, it’s you, Dalgar.”

“Brule!” cried the young Farsunian. “Quick! Tu, the chief councilor, lies in yonder side street, senseless—mayhap murdered!”

The Pict was off his horse in an instant, sword flashing into his hand. He flung the reins over his mounts head and left the steed standing there like a statue while he followed Dalgar on a run.

Together they bent over the stricken councilor while Brule ran an experienced hand over him.

“No fracture, apparently,” grunted the Pict. “Can’t tell for sure, of course. Was his beard off when you found him?”

“No, I pulled it off accidentally—”

“Then likely this is the work of some thug who knew him not. I’d rather think that. If the man who struck him down knew he was Tu, there’s black treachery brewing in Valusia. I told him he’d come to grief prowling around the city disguised this way—but you cannot tell a councilor anything. He insisted that in this manner he learned all that was going on; kept his finger on the empire’s pulse, as he said.”

“But if it were a cutthroat,” said Dalgar, “why did they not rob him? Here is his purse with a few copper coins in it—and who would seek to rob a beggar?”

The Spear-slayer swore. “Right. But who in Valka’s name could know he was Tu? He never wore the same disguise twice, and only Dondal and a slave helped him with it. And what did they want, whoever struck him down? Oh well, Valka—he’ll die while we stand here jabbering. Help me get him on my horse.”

With the chief councilor lolling drunkenly in the saddle, upheld by Brule’s steel-sinewed arms, they clattered through the streets to the palace. They were admitted by a wondering guard, and the senseless man was carried to an inner chamber and laid on a couch, where he was showing signs of recovering consciousness, under the ministrations of the slaves and court women.

At last he sat up and gripped his head, groaning. Ka-nu, Pictish ambassador and the craftiest man in the Kingdom, bent over him.

“Tu! Who smote you?”

“I don’t know,” the councilor was still dazed. “I remember nothing.”

“Had you any documents of importance about you?”

“No.”

“Did they take anything from you?”

Tu began fumbling at his garments uncertainly; his clouded eyes began to clear, then flared in sudden apprehension. “The ring! The royal signet ring! It is gone!”

Ka-nu smote his fist into his palm and cursed soulfully.

“This comes of carrying the thing with you! I warned you! Quick, Brule, Kelkor—Dalgar; foul treason is afoot! Haste to the king’s chamber.”

In front of the royal bedchamber, ten of the Red Slayers, men of the king’s favorite regiment, stood at guard. To Ka-nu’s staccato questions, they answered that the king had retired an hour or so ago, that no one had sought entrance, and that they had heard no sound.

Ka-nu knocked on the door. There was no response. In a panic he pushed against the door. It was locked from within.

“Break that door down!” he screamed, his face white, his voice unnatural with unaccustomed strain.

Two of the Red Slayers, giants in size, hurled their full weight against the door, but it, being of heavy oak braced with bronze bands, held. Brule pushed them away and attacked the massive portal with his sword. Under the heavy blows of the keen edge, wood and metal gave way, and in a few moments Brule shouldered through the shreds and rushed into the room. He halted short with a stifled cry, and, glaring over his shoulder, Ka-nu clutched wildly at his beard. The royal bed was mussed as if it had been slept in, but of the king there was no sign. The room was empty, and only the open window gave hint of any clue.

“Sweep the streets!” roared Ka-nu. “Comb the city! Guard all the gates! Kelkor, rouse out the full force of the Red Slayers. Brule, gather your horsemen and ride them to death if necessary. Haste! Dalgar—”

But the Farsunian was gone. He had suddenly remembered that the hour of midnight approached, and of far more importance to him than the whereabouts of any king was the fact that Nalissa bora Ballin was awaiting him in the Accursed Gardens two miles beyond the city wall.

That night Kull had retired early. As was his custom, he halted outside the door of the royal bedchamber for a few minutes to chat with the guard, his old regimental mates, and exchange a reminiscence or so of the days when he had ridden in the ranks of the Red Slayers. Then, dismissing his attendants, he entered the chamber, flung back the covers of his bed, and prepared to retire. Strange proceedings for a king, no doubt, but Kull had been long used to the rough life of a soldier, and before that he had been a savage tribesman. He had never gotten used to having things done for him, and in the privacy of his bedchamber he would at least attend to himself.

But just as he turned to extinguish the candle which illumined his room, he heard a slight tapping at the window sill. Hand on sword, he crossed the room with the easy, silent tread of a great panther and looked out. The window opened on the inner grounds of the palace; the hedges and trees loomed vaguely in the semi-darkness of the starlight. Fountains glimmered vaguely, and he could not make out the forms of any of the sentries who paced those confines.

But here at his elbow was mystery. Clinging to the vines which covered the wall was a small wizened fellow who looked much like the professional beggars which swarmed the more sordid of the city’s streets. He seemed harmless with his thin limbs and monkey face, but Kull regarded him with a scowl.

“I see I shall have to plant sentries at the very foot of my window, or tear these vines down,” said the king. “How did you get through the guards?”

The wizened one put his skinny finger across puckered lips for silence; then with a simian-like dexterity, slid a hand through the bars. He silently handed Kull a piece of parchment. The king unrolled it and read: “King Kull: If you value your life, or the welfare of the kingdom, follow this guide to the place where he shall lead you. Tell no one. Let yourself be not seen by the guards. The regiments are honey-combed with treason, and if you are to live and hold the throne, you must do exactly as I say. Trust the bearer of this note implicitly.” It was signed “Tu, Chief Councilor of Valusia” and was sealed with the royal signet ring.

Kull knit his brows. The thing had an unsavory look—but this was Tu’s handwriting—he noted the peculiar, almost imperceptible, quirk in the last letter of Tu’s name, which was the councilor’s trademark, so to speak. And then the sign of the seal, the seal which could not be duplicated. Kull sighed.

“Very well, he said. "Wait until I arm myself.”

Dressed and clad in light chain-mail armor, Kull turned again to the window. He gripped the bars, one in each hand, and cautiously exerting his tremendous strength, felt them give until even his broad shoulders could slip between them. Clambering out, he caught the vines and swung down them with as much ease as was displayed by the small beggar who preceded him. At the foot of the wall, Kull caught his companion’s arm.

“How did you elude the guard?” he whispered.

“To such as accosted me, I showed the sign of the royal seal.”

“That will scarcely suffice now,” grunted the king. “Follow me; I know their routine.”

Some twenty minutes followed of lying in wait behind a hedge or tree until a sentry passed, of dodging quickly into the shadows and making short, stealthy dashes. At last they came to the outer wall. Kull took his guide by the ankles and lifted him until his fingers clutched the top of the wall. Once astride it, the beggar reached down a hand to aid the king; but Kull, with a contemptuous gesture, backed off a few paces, took a short run, and bounding high in the air, caught the parapet with one upflung hand, swinging his great form up across the top of the wall with an almost incredible display of strength and agility.

The next instant the two strangely incongruous figures had dropped down on the opposite side and faded into the gloom.

Nalissa, daughter of the house of bora Ballin, was nervous and frightened. Upheld by her high hopes and her sincere love, she did not regret her rash actions of the last few hours, but she earnestly wished for the coming of midnight and her lover.

Up to the present, her escapade had been easy. It was not easy for anyone to leave the city after nightfall, but she had ridden away from her father’s house just before sundown, telling her mother that she was going to spend the night with a girl friend. It was well for her that women were allowed unusual freedom in the city of Valusia, and were not kept hemmed in seraglios and veritable prison houses as they were in the Eastern empires; a custom which survived the Flood.

Nalissa had ridden boldly through the eastern gate, and then made directly for the Accursed Gardens, two miles east of the city. These Gardens had once been the pleasure resort and country estate of a nobleman, but tales of grim debauches and ghastly rites of devil worship began to get abroad; and finally the people, maddened by the regular disappearance of their children, had descended on the Gardens in a frenzied mob and had hanged the prince to his own portals. Combing the Gardens, the people had found foul things, and in a flood of repulsion and horror had partially destroyed the mansion and the summer houses, the arbors, the grottoes, and the walls. But built of imperishable marble, many of the buildings had resisted both the sledges of the mob and the corrosion of time. Now, deserted for a hundred years, a miniature jungle had sprung up within the crumbling walls and rank vegetation overran the ruins.

Nalissa concealed her steed in a ruined summer house, and seated herself on the cracked marble floor, settling down to wait. At first it was not bad. The gentle summer sunset flooded the land, softening all scenes with its mellow gold. The green sea about her, shot with white gleams which were marble walls and crumbling roofs, intrigued her. But as night fell and the shadows merged, Nalissa grew nervous. The night wind whispered grisly things through the branches and the broad palm leaves and the tall grass, and the stars seemed cold and far away. Legends and tales came back to her, and she fancied that above the throb of her pounding heart she could hear the rustle of unseen black wings and the mutter of fiendish voices.

She prayed for midnight and Dalgar. Had Kull seen her then he would not have thought of her strange deep nature, nor the signs of her great future; he would have seen only a frightened little girl who passionately desired to be taken up and cuddled. But the thought of leaving never entered her mind.

Time seemed as if it would never pass, but pass it did somehow. At last a faint glow betrayed the rising of the moon, and she knew the hour was closing to midnight.

Then suddenly there came a sound which brought her to her feet, her heart flying into her throat. Somewhere in the supposedly deserted Gardens there crashed into the silence a shout and a clang of steel. A short, hideous scream chilled the blood in her veins; then silence fell in a suffocating shroud.

Dalgar—Dalgar! The thought beat like a hammer in her dazed brain. Her lover had come and had fallen foul of someone—or something.

She stole from her hiding place, one hand over her heart which seemed about to burst through her ribs. She stole along a broken pave, and the whispering palm leaves brushed against her like ghostly fingers. About her lay a pulsating gulf of shadows, vibrant and alive with nameless evil. There was no sound.

Ahead of her loomed the ruined mansion; then without a sound, two men stepped into her path. She screamed once; then her tongue froze with terror. She tried to flee, but her legs would not work, and before she could move, one of the men had caught her up and tucked her under his arm as if she were a tiny child.

“A woman,” he growled in a language which Nalissa barely understood, and which she recognized as Verulian. “Lend me your dagger and I’ll—”

“We haven’t time now,” interposed the other, speaking in the Valusian tongue. “Toss her in there with him, and we’ll finish them both together. We must get Phondar here before we kill him; he wants to question him a little.”

“Small use,” rumbled the Verulian giant, striding after his companion. “He won’t talk—I can tell you that—he’s opened his mouth only to curse us, since we captured him.”

Nalissa, tucked ignominiously under her captor’s arm, was frozen with fear, but her mind was working. Who was this “him” they were going to question and then kill? The thought that it must be Dalgar drove her own fear from her mind, and flooded her soul with a wild and desperate rage. She began to kick and struggle violently and was punished with a resounding smack that brought tears to her eyes and a cry of pain to her lips. She lapsed into a humiliated submission and was presently tossed unceremoniously through a shadowed doorway, to sprawl in a disheveled heap on the floor.

“Hadn’t we better tie her?” queried the giant.

“What use? She can’t escape. And she can’t untie him. Hurry up; we’ve got work to do.”

Nalissa sat up and looked timidly about. She was in a small chamber, the corners of which were screened with spider webs. Dust was deep on the floor, and fragments of marble from the crumbling walls littered it. Part of the roof was gone, and the slowly rising moon poured light through the aperture. By its light she saw a form on the floor, close to the wall. She shrank back, her teeth sinking into her lip with horrified anticipation; then she saw with a delirious sensation of relief that the man was too large to be Dalgar. She crawled over to him and looked into his face. He was bound hand and foot and gagged; above the gag, two cold gray eyes looked up into hers.

“King Kull!” Nalissa pressed both hands against her temples while the room reeled to her shocked and astounded gaze. The next instant her slim, strong fingers were at work on the gag. A few minutes of agonized effort, and it came free. Kull stretched his jaws and swore in his own language, considerate, even in that moment, of the girl’s tender ears.

“Oh, my lord, how came you here?” The girl was wringing her hands.

“Either my most trusted councilor is a traitor or I am a madman!” growled the giant. “One came to me with a letter in Tu’s handwriting, bearing even the royal seal. I followed him, as instructed, through the city and to a gate, the existence of which I had never known. This gate was unguarded and apparently unknown to any but they who plotted against me. Outside the gate, one awaited us with horses, and we came full speed to these damnable gardens. At the outer edge we left the horses, and I was led, like a blind, dumb fool for sacrifice, into this ruined mansion.

“As I came through the door, a great man-net fell on me, entangling my sword arm and binding my limbs, and a dozen rogues sprang on me. Well, mayhap my taking was not so easy as they had thought Two of them were swinging on my already encumbered right arm so I could not use my sword, but I kicked one in the side and felt his ribs give way, and bursting some of the net’s strands with my left hand, I gored another with my dagger. He had his death thereby and screamed like a lost soul as he gave up the ghost.

“But by Valka, there were too many of them. At last they had me stripped of my armor,”—Nalissa saw the king wore only a sort of loincloth—“and bound as you see me. The devil himself could not break these strands; no, scant use to try to untie the knots. One of the men was a seaman, and I know of old the sort of knots they tie. I was a galley slave once, you know.”

“But what can I do?” wailed the girl, wringing her hands.

“Take a heavy piece of marble and flake off a sharp sliver,” said Kull swiftly. “You must cut these ropes—”

She did as he bid and was rewarded with a long thin piece of stone, the concave edge of which was as keen as a razor with a jagged edge.

“I fear I will cut your skin, sire,” she apologized as she began work.

“Cut skin, flesh, and bone, but get me free!” snarled Kull, his eyes blazing. “Trapped like a blind fool! Oh, imbecile that I am! Valka, Honan, and Hotath! But let me get my hands on the rogues—how came you here?”

“Let us talk of that later,” said Nalissa rather breathlessly. “Just now there is time for haste.”

Silence fell as the girl sawed at the stubborn strands, giving no heed to her own tender hands, which were soon lacerated and bleeding. Slowly, strand by strand, the cords gave way; but there were still enough to hold the ordinary man helpless when a heavy step sounded outside the door.

Nalissa froze. A voice spoke, “He is within, Phondar, bound and gagged. With him is some Valusian wench that we caught wandering about the Gardens.”

“Then be on watch for some gallant,” spoke another voice, whose harsh, grating tones were those of a man accustomed to being obeyed. “Likely she was to meet some fop here. You—”

“No names, no names, good Phondar,” broke in a silky Valusian voice. “Remember our agreement; until Gomlah mounts the throne, I am simply—the Masked One.”

“Very good,” grunted the Verulian. “You have done a good night’s work, Masked One. None but you could have done it, for only you knew how to obtain the royal signet. Only you could so closely counterfeit Tu’s writing—by the way, did you kill the old fellow?”

“What matter? Tonight, or the day Gomlah mounts the throne, he dies. The matter of most importance is that the king lies helpless in our power.”

Kull was racking his brain trying to place the hauntingly familiar voice of the traitor. And Phondar—his face grew grim. A deep conspiracy indeed, if Verulia must send the commander of her royal armies to do her foul work. The king knew Phondar well, and had aforetime entertained him in the palace.

“Go in and bring him out,” said Phondar. “We will take him to the old torture chamber. I have questions to ask of him.”

The door opened, admitting one man: the giant who had captured Nalissa. The door closed behind him and he crossed the room, giving scarcely a glance to the girl who cowered in a corner. He bent over the bound king, took him by leg and shoulder to lift him bodily; there came a sudden loud snap as Kull, throwing all his iron strength into one convulsive wrench, broke the remaining strands which bound him.

He had not been tied long enough for all circulation to be cut off and his strength affected thereby. As a python strikes, his hands shot to the giant’s throat; shot, and gripped like a steel vise.

The giant went to his knees. One hand flew to the fingers at his throat, the other to his dagger. His fingers sank like steel into Kull’s wrist, the dagger flashed from its sheath; then his eyes bulged, his tongue sagged out. The fingers fell away from the king’s wrist, and the dagger slipped from a nerveless grip. The Verulian went limp, his throat literally crushed in that terrible grip. Kull, with one terrific wrench, broke his neck and, releasing him, tore the sword from its sheath. Nalissa had picked up the dagger.

The combat had taken only a few flashing seconds and had caused no more noise than might have resulted from a man lifting and shouldering a great weight.

“Hasten!” called Phondar’s voice impatiently from beyond the door, and Kull, crouching tigerlike just inside, thought quickly. He knew that there were at least a score of conspirators in the Gardens. He knew also, from the sound of voices, that there were only two or three outside the door at the moment. This room was not a good place to defend. In a moment they would be coming in to see what occasioned the delay. He reached a decision and acted promptly.

He beckoned the girl. “As soon as I have gone through the door, run out likewise and go up the stairs which lead away to the left.” She nodded, trembling, and he patted her slim shoulder reassuringly. Then he whirled and flung open the door.

To the men outside, expecting the Verulian giant with the helpless king on his shoulders, appeared an apparition which was dumbfounding in its unexpectedness. Kull stood in the door; Kull, half-naked, crouching like a great human tiger, his teeth bared in a snarl of battle fury, his eyes blazing. His sword blade whirled like a wheel of silver in the moonlight.

Kull saw Phondar, two Verulian soldiers, a slim figure in a black mask—a flashing instant, and then he was among them and the dance of death was on. The Verulian commander went down in the king’s first lunge, his head cleft to the teeth in spite of his helmet.

The Masked One drew and thrust, his point raking Kull’s cheek; one of the soldiers drove at the king with a spear, was parried, and the next instant lay dead across his master. The remaining soldier broke and ran, yelling lustily for his comrades. The Masked One retreated swiftly before the headlong attack of the king, parrying and guarding with an almost uncanny skill. He had no time to launch an attack of his own; before the whirlwind ferocity of Kull’s charge he had only time for defense. Kull beat against his blade like a blacksmith on an anvil, and again and again it seemed as though the long Verulian steel must inevitably cleave that masked and hooded head, but always the long slim Valusian sword was in the way, turning the blow by an inch or stopping it within a hair’s-breadth of the skin, but always just enough.

Then Kull saw the Verulian soldiers running through the foliage and heard the clang of their weapons and their fierce shouts. Caught here in the open, they would get behind him and slit him like a rat. He slashed once more, viciously, at the retreating Valusian, and then, backing away, turned and ran fleetly up the stairs, at the top of which Nalissa already stood.

There he turned at bay. He and the girl stood on a sort of artificial promontory. A stair led up, and a stair had once led down the other way, but now the back stair had long since crumbled away. Kull saw that they were in a cul-de-sac. The walls were cut deep with ornate carvings but— Well, thought Kull, here we die. But here many others die, too.

The Verulians were gathering at the foot of the stair, under the leadership of the mysterious masked Valusian. Kull took a fresh grip on his sword hilt and flung back his head, an unconscious reversion to days when he had worn a lion-like mane of hair.

Kull had never feared death; he did not fear it now, and, except for one consideration, he would have welcomed the clamor and madness of battle as an old friend, without regrets. This consideration was the girl who stood beside him. As he looked at her trembling form and white face, he reached a sudden decision.

He raised his hand and shouted, “Ho, men of Verulia! Here I stand at bay. Many shall fall before I die. But promise me to release the girl, unharmed, and I will not lift a hand. You may then kill me like a sheep.”

Nalissa cried in protest, and the Masked One laughed. “We make no bargains with one already doomed. The girl also must die, and I make no promises to be broken. Up, warriors, and take him!”

They flooded the stair like a black wave of death, swords sparkling like frosty silver in the moonlight. One was far in advance of his fellows, a huge warrior who bore on high a great battle-axe. Moving quicker than Kull had anticipated, this man was on the landing in an instant. Kull rushed in, and the axe descended. He caught the heavy shaft with his left hand and checked the downward rush of the weapon in mid-air—a feat few men could have done—and at the same time struck in from the side with his right, a sweeping hammerlike blow which sent the long sword crunching through armor, muscle, and bone, and left the broken blade wedged in the spinal column.

At the same instant, he released the useless hilt and tore the axe from the nerveless grasp of the dying warrior, who pitched back down the stairs. And Kull laughed shortly and grimly.

The Verulians hesitated on the stair, and, below, the Masked One savagely urged them on. They were inclined to be rebellious.

“Phondar is dead,” shouted one. “Shall we take orders from this Valusian? This is a devil and not a man who faces us! Let us save ourselves!”

“Fools!” the Masked One’s voice rose in a ferine shriek. “Don’t you see that your own safety lies in slaying the king? If you fail tonight, your own government will repudiate you and will aid the Valusians in hunting you down! Up, fools! You will die, some of you, but better for a few to die under the king’s axe than for all to die on the gibbet! Let one man retreat down these stairs—that man will I kill!” And the long, slender sword menaced them.

Desperate, afraid of their leader, and recognizing the truth of his words, the score or more of warriors turned their breasts to Kull’s steel. As they massed for what must necessarily be the last charge, Nalissa’s attention was attracted by a movement at the base of the wall. A shadow detached itself from the rest of the shadows and moved up the sheer face of the wall, climbing like an ape and using the deep carvings for foot and hand holds. This side of the wall was in shadow, and she could not make out the features of the man; moreover, he wore a heavy morion which shaded his face.

Saying nothing to Kull, who stood at the landing, his axe poised, she stole over to the edge of the wall, half concealing herself behind a ruin of what had once been a parapet. Now she could see that the man was in full armor, but still she could not make out his features. Her breath came fast, and she raised the dagger, fighting fiercely to overcome a tendency of nausea.

Now a steel-clad arm hooked up over the edge—she sprang as quickly and silently as a tigress and struck full at the unprotected face suddenly upturned in the moonlight. And even as the dagger fell, and she was unable to cheek the blow, she screamed, wildly and agonizedly. For in that fleeting second, she recognized the face of her lover, Dalgar of Farsun.

Dalgar, after unceremoniously leaving the distracted presence of Ka-nu, ran to his horse and rode hard for the eastern gate. He had heard Ka-nu give orders to close the gates and let no one out, and he rode like a madman to beat that order. It was a hard matter to get out at night anyway, and Dalgar, having learned that the gates were not guarded tonight by the incorruptible Red Slayers, had planned to bribe his way out. Now he depended upon the audacity of his scheme.

All in a lather of sweat, he halted at the eastern gate and shouted, “Unbolt the gate! I must ride to the Verulian border tonight! Quickly! The king has vanished! Let me through and then guard the gate! In the name of the king!”

Then, as the soldier hesitated, “Haste, fools! The king may be in mortal danger! Hark!”

Far out across the city, chilling hearts with sudden nameless dread, sounded the deep tones of the great bronze Bell of the King, which booms only when the king is in peril. The guards were electrified. They knew Dalgar was high in favor as a visiting noble. They believed what he said, so, under the impetuous blast of his will, they swung the great iron gates wide, and he shot through like a thunderbolt, to vanish instantly in the outer darkness.

As Dalgar rode, he hoped no great harm had come to Kull, for he liked the bluff barbarian far more than he had ever liked any of the sophisticated and bloodless kings of the Seven Empires. Had it been possible, he would have aided in the search. But Nalissa was waiting for him, and already he was late.

As the young nobleman entered the Gardens, he had a peculiar feeling that here in the heart of desolation and loneliness there were many men. An instant later he heard a clash of steel, the sound of many running footsteps, and a fierce shouting in a foreign tongue. Slipping off his horse and drawing his sword, he crept through the underbrush until he came in sight of the ruined mansion. There a strange sight burst upon his vision. At the top of the crumbling staircase stood a half-naked, blood-stained giant whom he recognized as the king of Valusia. By his side stood a girl—a half-stifled cry burst from Dalgar’s lips. Nalissa! His nails bit into the palms of his clenched hand. Who were those men in dark clothing who swarmed up the stairs? No matter. They meant death to the girl and to Kull. He heard the king challenge them and offer his life for Nalissa’s, and a flood of gratitude engulfed him. Then he noted the deep carvings on the wall nearest him. The next instant he was climbing, to die by the side of the king, protecting the girl he loved.

He had lost sight of Nalissa, and now as he climbed he dared not take the time to look up for her. This was a slippery and treacherous task. He did not see her until he caught hold of the edge to pull himself up; then he heard her scream and saw her hand falling toward his face, gripping a gleam of silver. He ducked and took the blow on his morion; the dagger snapped at the hilt, and Nalissa collapsed in his arms the next moment.

Kull had whirled, axe high, at her scream; now he paused. He recognized the Farsunian, and even in that instant he read between the lines. He knew why the couple were here and grinned with real enjoyment.

A second the charge had halted, as the Verulians had noted the second man on the landing; now they came on again, bounding up the steps in the moon-light, blades gleaming, eyes wild with desperation. Kull met the first with an overhand smash that crushed helmet and skull; then Dalgar was at his side, and his blade licked out and into a Verulian throat.

Then began the battle of the stair, since immortalized by singers and poets.

Kull was there to die and to slay before he died. He gave scant thought to defense. His axe played a wheel of death about him, and with each blow there came a crunch of steel and bone, a spurt of blood, a gurgling cry of agony. Bodies choked the wide stair, but still the survivors came, clambering over the gory forms of their comrades.

Dalgar had little opportunity to thrust or cut. He had seen in an instant that his best task lay in protecting Kull, who was a born killer, but who, in his armor-less condition, was likely to fall at any instant. So Dalgar wove a web of steel about the king, bringing into play all the sword skill that was his. Again and again his flashing blade turned a point from Kull’s heart; again and again his mail-clad forearm intercepted a blow that else had killed. Twice he took on his own helmet slashes meant for the king’s bare head.

It is not easy to guard another man and yourself at the same time. Kull was bleeding from cuts on the face and breast, from a gash above the temple, a stab in the thigh, and a deep wound in the left shoulder; a thrusting pike had rent Dalgar’s cuirass and wounded him in the side, and he felt his strength ebbing. A last mad effort of their foes and the Farsunian was over-thrown. He fell at Kull’s feet, and a dozen points prodded for his life. With a lion-like roar, Kull cleared a space with one mighty sweep of his red axe and stood astride the fallen youth. They closed in—

There burst on Kull’s ears a crash of horses’ hoofs and the Accursed Gardens were flooded with wild riders, yelling like wolves in the moonlight. A storm of arrows swept the stairs, and men howled, pitching headlong to lie still, or to tear at the cruel, deeply embedded shafts. The few whom Kull’s axe and the arrows had left fled down the stairs to be met at the bottom by the whistling curved swords of Brule’s Picts. And there they died, fighting to the last, those bold Verulian warriors—cat’s-paws for their false king, sent out on a dangerous and foul mission, disowned by the man who sent them out, and branded forever with infamy. But they died like men.

But one did not die there at the foot of the stairs. The Masked One had fled at the first sound of hoofs, and now he shot across the Gardens riding a superb horse. He had almost reached the outer wall when Brule, the Spear-slayer, dashed across his path. There on the promontory, leaning on his bloody axe, Kull saw them fight beneath the moon.

The Masked One had abandoned his defensive tactics. He charged the Pict with reckless courage, and the Spear-slayer met him, horse to horse, man to man, blade to blade. Both were magnificent horsemen. Their steeds, obeying the touch of the bridle, the nudge of the knee, whined, reared, and spun. But through all their motions, the whistling blades never lost touch of each other. Brule, unlike his tribesmen, used the slim straight sword of Valusia. In reach and speed there was little difference between them, and Kull, watching, again and again caught his breath and bit his lip as it seemed Brule would fall before an unusually vicious thrust.

No crude hacking and slashing for these seasoned warriors. They thrust and countered, parried and thrust again. Then suddenly Brule seemed to lose touch with his opponent’s blade—he parried wildly, leaving himself wide open—the Masked One struck heels into his horse’s side as he lunged, so that the sword and horse shot forward as one. Brule leaned aside, let the blade glance from the side of his cuirass; his own blade shot straight out, elbow, wrist, hilt, and point making a straight line from his shoulder. The horses crashed together and together they rolled headlong on the sward. But from that tangle of lashing hoofs Brule rose unharmed, while there in the grass lay the Masked One. Brule’s sword still transfixing him.

Kull awoke as from a trance; the Picts were howling about like wolves, but he raised his hand for silence. “Enough! You are all heroes! But attend to Dalgar; he is sorely wounded. And when you have finished, you might see to my own wounds. Brule, how came you to find me?”

Brule beckoned Kull to where he stood above the dead Masked One.

“A beggar crone saw you climb the palace wall, and out of curiosity watched where you went. She followed and saw you go through the forgotten gate. I was riding the plain between the wall and these Gardens when I heard the clash of steel. But who can this be?”

“Raise the mask,” said Kull, “Whoever it is, it is he who copied Tu’s handwriting, who took the signet ring from Tu, and—”

Brule tore the mask away.

“Dondal!” Kull ejaculated. “Tu’s nephew! Brule, Tu must never know this. Let him think that Dondal rode with you and died fighting for his king.”

Brule seemed stunned. “Dondal! A traitor! Why, many a time I’ve drunk wine with him and slept it off in one of his beds.”

Kull nodded. “I liked Dondal.”

Brule cleansed his blade and drove it home in the scabbard with a vicious clank. “Want will make a rogue of any man,” he said moodily. “He was deep in debt—Tu was penurious with him. Always maintained that giving young men money was bad for them. Dondal was forced to keep up appearances for his pride’s sake, and so fell into the hands of the usurers. Thus Tu is the greater traitor, for he drove the boy into treachery by his parsimony—and I could wish Tu’s heart had stopped my point instead of his.”

So saying, the Pict turned on his heel and strode sombrely away.

Kull turned back to Dalgar, who lay half-senseless while the Pictish warriors dressed his wounds with experienced fingers. Others attended to the king, and while they staunched, cleansed, and bandaged, Nalissa came up to Kull.

“Sire,” she held out her small hands, now scratched and stained with dried blood, “will you now have mercy on us—grant my plea if—” her voice caught on a sob—“if Dalgar lives?”

Kull caught her slim shoulders and shook her in his anguish.

“Girl, girl, girl! Ask me anything except something I cannot grant. Ask half my kingdom or my right hand, and it is yours. I will ask Murom to let you marry Dalgar—I will beg him—but I cannot force him.”

Tall horsemen were gathering through the Gardens, whose resplendent armor shone among the half-naked, wolfish Picts. A tall man hurried up, throwing back the vizor of his helmet.

“Father!”

Murom bora Ballin crushed his daughter to his breast with a sob of thanksgiving, and then turned to his king.

“Sire, you are sorely wounded!”

Kull shook his head. “Not sorely; at least, not for me, though other men might feel stiff and sore. But yonder lies he who took took the death thrusts meant for me; who was my shield and my helmet, and but for whom Valusia had howled for a new king.”

Murom whirled toward the prostrate youth.

“Dalgar! Is he dead?”

“Nigh unto it,” growled a wiry Pict who was still working above him. “But he is steel and whalebone; with any care he should live.”

“He came here to meet your daughter and elope with her,” said Kull, while Nalissa hung her head. “He crept through the brush and saw me fighting for my life and hers, atop yonder stair. He might have escaped. Nothing barred him. But he climbed the sheer wall to certain death, as it seemed then, and fought by my side as gayly as he ever rode to a feast—and he not even a subject of mine by birth.”

Murom’s hands clenched and unclenched. His eyes kindled and softened as they bent on his daughter.

“Nalissa,” he said softly, drawing the girl into the shelter of his steel-clad arm, “do you still wish to marry this reckless youth?”

Her eyes spoke eloquently enough.

Kull was speaking, “Take him up carefully and bear him to the palace; he shall have the best—”

Murom interposed, “Sire, if I may ask; let him be taken to my castle. There the finest physicians shall attend him and on his recovery—well, if it be your royal pleasure, might we not celebrate the event with a wedding?”

Nalissa screamed with joy, clapped her hands, kissed her father and Kull, and was off to Dalgar’s side like a whirlwind.

Murom smiled softly, his aristocratic face alight.

“Out of a night of blood and terror, joy and happiness are born.”

The barbarian king grinned and shouldered his stained and notched axe.

“Life is that way, Count; one man’s bane is another’s bliss.”