Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

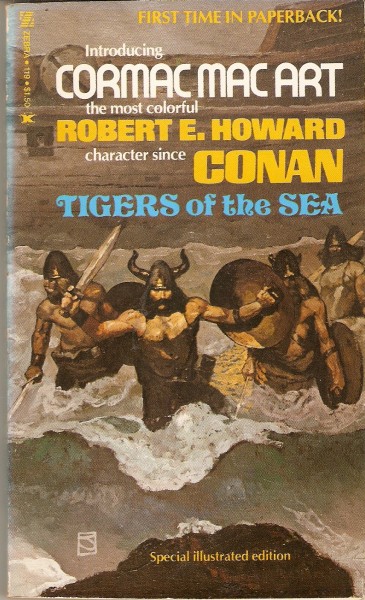

Published in Tigers of the Sea, 1974.

“Skoal!” The smoke-stained rafters shook as the deep-throated roar went up. Drinking horns clashed and sword hilts beat upon the oaken board. Dirks hacked at the great joints of meat, and under the feet of the revelers gaunt, shaggy wolf-hounds fought over the remnants.

At the head of the board sat Rognor the Red, scourge of the Narrow Seas. The huge Viking meditatively stroked his crimson beard, while his great, arrogant eyes roved about the hall, taking in the familiar scene. A hundred warriors feasted here, waited on by bold-eyed, yellow-haired women and by trembling slaves. Spoils of the Southland were flung about in careless profusion. Rare tapestries and brocades, bales of silk and spice, tables and benches of fine mahogany, curiously chased weapons and delicate masterpieces of art vied with the spoils of the hunt—horns and heads of forest beasts. Thus the Viking proclaimed his mastery over man and beast.

The Northern nations were drunken with victory and conquest. Rome had fallen; Frank, Goth, Vandal and Saxon had looted the fairest possessions of the world. And now these races found themselves hard put to hold their prizes from the wilder, fiercer peoples who swept down on them from the blue mists of the North. The Franks, already settled in Gaul and beginning to show signs of Latinization, found the long, lean galleys of the Norsemen bringing the sword up their rivers; the Goth further south felt the weight of their kinsmen’s fury and the Saxons, forcing the Britons westward, found themselves assailed by a more furious foe from the rear. East, west and south to the ends of the world ranged the dragon-beaked long ships of the Vikings. The Norse had already begun to settle in the Hebrides and the Orkneys, though as yet it was more a rendezvous of pirates than the later colonization. And the lair of Rognor the Red was this isle, called by the Scots Ladbhan, the Picts Golmara and the Norse Valgaard. His word was law, the only law this wild horde recognized; his hand was heavy, his soul ruthless, his range the open world.

The sea-king’s eyes ranged about the board, while he nodded slightly in satisfaction. No pirate that sailed the seas could boast a fiercer assortment of fighting men than he; a mixed horde they were, Norsemen and Jutes—big, yellow-bearded men with wild, light eyes. Even now as they feasted they were fully armed and girt in mail, though they had laid aside their horned helmets. A ferocious, wayward race they were, with a latent madness burning in their brains, ready to leap into terrible flame at an instant.

Rognor’s gaze turned from them, with their great bare arms heavy with golden armlets, to rest on one who seemed strangely different from the rest. This was a tall, rangily built man, deep-chested and strong, whose square-cut black hair and dark, smooth face contrasted with the yellow manes and beards about him. This man’s eyes were narrow slits and of a cold-steel grey, and they, with a number of scars that marred his face, lent him a peculiarly sinister aspect. He wore no gold ornaments of any kind and his mail was of chain mesh instead of the scale type worn by the men about him.

Rognor frowned abstractedly as he eyed this man, but just as he was about to speak, another man entered the huge hall and approached the head of the board. This newcomer was a tall, splendidly made young Viking, beardless but wearing a yellow mustache. Rognor greeted him.

“Hail, Hakon! I have not seen you since yesterday.”

“I was hunting wolves in the hills,” answered the young Viking, glancing curiously at the dark stranger. Rognor followed his gaze.

“That is one Cormac Mac Art, chief of a band of reivers. His galley was wrecked in the gale last night and he alone won through the breakers to shore. He came to the skalli doors early in the dawn, dripping wet, and argued the carles into bringing him in to me instead of slaying him as they had intended. He offered to prove his right to follow me on the Viking path, and fought my best swordsmen, one after the other, weary as he was. Rane, Tostig, and Halfgar he played with as they were children and disarmed each without giving scathe or taking a wound himself.”

Hakon turned to the stranger and spoke a courtly greeting, and the Gael answered in kind, with a stately inclination of his head.

“You speak our language well,” said the young Viking.

“I have many friends among your people,” answered Cormac. Hakon’s eyes rested on him strangely for a moment, but the inscrutable eyes of the Gael gave back the gaze, with no hint of what was going on in his mind.

Hakon turned back to the sea-king. Irish pirates were common enough in the Narrow Seas, and their forays carried them sometimes as far as Spain and Egypt, though their ships were far less seaworthy than the long ships of the Vikings. But there was little friendship between the races. When a reiver met a Viking, generally a ferocious battle ensued. They were rivals of the Western seas.

“You have come at a good time, Cormac,” Rognor was rumbling. “You will see me take a wife tomorrow. By the hammer of Thor! I have taken many women in my time—from the people of Rome and Spain and Egypt, from the Franks, from the Saxons, and from the Danes, the curse of Loki on them!. But never have I married one before. Always I tired of them and gave them to my men for sport. But it is time I thought of sons and so I have found a woman, worthy even of the favors of Rognor the Red. Ho—Osric, Eadwig, bring in the British wench! You shall judge for yourself, Cormac.”

Cormac’s eyes roved to where Hakon sat. To the casual watcher the young Viking seemed disinterested, almost bored. But the Gael’s stare centered on the angle of his firm jaw as he caught the sudden, slight ripple of muscle that betrays controlled tenseness. The Gael’s cold eyes flickered momentarily.

Three women entered the feasting-hall, closely followed by the two carles Rognor had sent for them. Two of the women led the third before Rognor, then fell back, leaving her facing him alone.

“See, Cormac,” rumbled the Viking: “is she not fit to bear the sons of a king?”

Cormac’s eyes traveled impersonally up and down the girl who stood panting with anger before him. A fine, robust figure of young womanhood she was, quite evidently not yet twenty years old. Her proud bosom heaved with angry defiance, and her bearing was that of a young queen rather than a captive. She was clad in the rather scanty finery of a Norse woman, but she was quite apparently not of their race. With her blond hair and blazing blue eyes, coupled with her snowy skin, she was evidently a Celt; but Cormac knew that she was not one of the softened and Latinized people of southern Britain. Her carriage and manner were as free and barbaric as that of her captors.

“She is the daughter of a chief of the western Britons,” said Rognor; “one of a tribe that never bowed the neck to Rome and now, hemmed between the Saxons on one side and the Picts of the other, holds both at bay. A fighting race! I took her from a Saxon galley, whose chief had in turn taken her captive during an inland raid. The moment I laid eyes on her, I knew she was the girl who should bear my sons. I have held her now for some months, having her taught our ways and language. She was a wildcat when we first caught her! I gave her in charge of old Eadna, a very she-bear of a woman—and by the hammer of Thor, the old valkyrie nearly met her match! It took a dozen birchings across old Eadna’s knee to tame the spit-fire—”

“Are you done with me, pirate?” flamed the girl suddenly, defiantly, yet with a tearful catch, barely discernible, in her voice. “If so, let me go back to my chamber—for the hag-face of Eadna, ugly as it is, is more pleasant to my sight than your red-bearded swine-face!”

A roar of mirth went up, and Cormac grinned thinly.

“It seems that her spirit is not utterly broken,” he commented dryly.

“I would not count her worth a broken twig if it were,” answered the sea-king, unabashed. “A woman without mettle is like a scabbard without a sword. You may return to your chamber, my pretty one, and prepare for your nuptials on the morrow. Mayhap you will look on me with more favor after you have borne me three or four stout sons!”

The girl’s eyes snapped blue fire, but without a word she turned her back squarely on her master and prepared to leave the hall—when a voice suddenly cut through the din:

“Hold!”

Cormac’s eyes narrowed as a grotesque and abhorrent figure came shambling and lurching across the hall. It was a creature with the face of a mature man, but it was no taller than a young boy, and its body was strangely deformed with twisted legs, huge malformed feet and one shoulder much higher than the other. Yet the fellow’s breadth and girth were surprising; a stunted, malformed giant he seemed. From a dark, evil face gleamed two great, yellow eyes.

“What is this?” asked the Gael. “I knew you Vikings sailed far, but I never heard that you sailed to the gates of Hell. Yet surely this thing had its birth nowhere else.”

Rognor grinned. “Aye, in Hell I caught him, for in many ways Byzantium is Hell, where the Greeks break and twist the bodies of babes that they may grow into such blasphemies as this, to furnish sport for the emperor and his nobles. What now, Anzace?”

“Great lord,” wheezed the creature in a shrill, loathly voice, “tomorrow you take this girl, Tarala, to wife—is it not? Aye—oh, aye! But, mighty lord, what if she loves another?”

Tarala had turned back and now bent on the dwarf a wide-eyed stare in which aversion and anger vied with fear.

“Love another?” Rognor drank deep and wiped his beard. “What of it? Few girls love the men they have to marry. What care I for her love?”

“Ah,” sneered the dwarf, “but would you care if I told you that one of your own men talked to her last night—aye, and for many nights before that—through the bars of her window?”

Down crashed the drinking-jack. Silence fell over the hall and all eyes turned toward the group at the head of the table. Hakon rose, flushing angrily.

“Rognor—” his hand trembled on his sword—“if you will allow this vile creature to insult your wife-to-be, I at least—”

“He lies!” cried the girl, reddening with shame and rage. “I—”

“Be silent!” roared Rognor. “You, too, Hakon. As for you—” his huge hand shot out and closed like a vise on the front of Anzace’s tunic—“speak, and speak quickly. If you lie—you die!”

The dwarf’s dusky hue paled slightly, but he shot a spiteful glance of reptilian malice toward Hakon. “My lord,” said he, “I have watched for many a night since I first saw the glances this girl exchanged with he who has betrayed you. Last night, lying close among the trees without her window, I heard them plan to flee tonight. You are to be robbed of your fine bride, master.”

Rognor shook the Greek as a mastiff shakes a rat. “Dog!” he roared. “Prove this or howl under the blood-eagle!”

“I can prove it,” purred the dwarf. “Last night I had another with me—one whom you know is a speaker of truth. Tostig!”

A tall, cruel-visaged warrior came forward, his manner one of sullen defiance. He was one of those on whom Cormac had proved his swordsmanship.

“Tostig,”, grinned the dwarf, “tell our master whether I speak truth—tell him if you lay in the bushes with me last night and heard his most trusted man—who was supposed to be up in the hills hunting—plot with this yellow-haired wench to betray their master and flee tonight.”

“He speaks truth,” said the Norseman sullenly.

“Odin, Thor and Loki!” snarled Rognor, flinging the dwarf from him and crashing his fist down on the board. “And who was the traitor?—tell me, that I may break his vile neck with my two hands!”

“Hakon!” screamed the dwarf, a quivering finger stabbing at the young Viking, his face writhing in a horrid contortion of venomous triumph. “Hakon, your right hand man!”

“Aye, Hakon it was,” growled Tostig.

Rognor’s jaw dropped, and for an instant a tense silence gripped the hall. Then Hakon’s sword was out like a flash of summer lightning and he sprang like a wounded panther at his betrayors. Anzace screeched and turned to run, and Tostig drew back and parried Hakon’s whistling stroke. But the fury of that headlong attack was not to be denied. Hakon’s single terrific blow shivered Tostig’s sword and flung the warrior at Rognor’s feet, brains oozing from his cleft skull. At the same time Tarala, with the desperate fury of a tigress, snatched up a bench and dealt Anzace such a blow as to stretch him stunned and bleeding on the floor.

The whole hall was in an uproar. Warriors roared their bewilderment and indecision as they shouldered each other and snarled out of the corners of their mouths, gripping their weapons and quivering with eagerness for action, but undecided which course to follow. Their two leaders were at variance, and their loyalty wavered. But close about Rognor were a group of hardened veterans who were assailed by no doubts. Their duty was to protect their chief at all times and this they now did, moving in a solid hedge against the enraged Hakon who was making a most sincere effort to detach the head of his former ally from its shoulders. Left alone, the matter might have been in doubt, but Rognor’s vassals had no intention of leaving their chief to fight his own battles. They closed in on Hakon, beat down his guard by the very weight of their numbers and stretched him on the floor, bleeding from a dozen minor cuts, where he was soon bound hand and foot. All up and down the hall the rest of the horde was pressing forward, exclaiming and swearing at each other, and there was some muttering and some black glances cast at Rognor; but the sea-king, sheathing the great sword with which he had been parrying Hakon’s vicious cuts, pounded on the board and shouted ferociously. The insurgents sank back, muttering, quelled by the blast of his terrific personality.

Anzace rose, glassy-eyed and holding his head. A great, bleak woman had wrested the bench away from Tarala and now held the blond girl tucked under her arm like an infant, while Tarala kicked and struggled and cursed. In the whole hall there was but one person who seemed not to share the general frenzy—the Gaelic pirate, who had not risen from his seat where he sipped his ale, with a cynical smile.

“You would betray me, eh?” bellowed Rognor, kicking his former lieutenant viciously. “You whom I trusted, whom I raised to high honor—” Words failed the outraged sea-king and he brought his feet into play again, while Tarala shrieked wrathful protests:

“Beast! Thief! Coward! If he were free you would not dare!”

“Be silent!” roared Rognor.

“I will not be silent!” she raged, kicking vainly in the old woman’s grasp. “I love him! Why should I not love him in preference to you? Where you are harsh and cruel, he is kind. He is brave and courteous, and the only man among you that has treated me with consideration in my captivity. I will marry him or no other—”

With a roar Rognor drew back his iron fist, but before he could crash it into that defiant, beautiful face, Cormac rose and caught his wrist. Rognor grunted involuntarily; the Gael’s fingers were like steel. For a moment the Norseman’s flaming eyes glared into the cold eyes of Cormac and neither wavered.

“You cannot marry a dead woman, Rognor,” said Cognac coolly. He released the other’s wrist and resumed his seat.

The sea-king growled something in his beard and shouted to his grim vassals: “Take this young dog and chain him in the cell; tomorrow he shall watch me marry the wench, and then she shall watch while with my own hands I cut the blood-eagle in his back.”

Two huge carles stolidly lifted the bound and raging Hakon, and as they started to bear him from the hall, he fell suddenly silent and his gaze rested full on the sardonic face of Cormac Mac Art. The Gael returned the glance, and suddenly Hakon spat a single word: “Wolf!”

Cormac did not start; not by the flicker of an eyelash did he betray any surprise. His inscrutable gaze did not alter as Hakon was borne from the hall.

“What of the wench, master?” asked the woman who held Tarala captive. “Shall I not strip her and birch her?”

“Prepare her for the marrying,” growled Rognor with an impatient gesture. “Take her out of my sight before I lose my temper and break her white neck!”

A torch in a niche of the wall flickered, casting an indistinct light about the small cell, whose floor was of dirt and whose walls and roof were of square-cut logs. Hakon the Viking, chained in the corner furthest from the door, just beneath the small, heavily-barred window, shifted his position and cursed fervently. It was neither his chains nor his wounds which caused his discomfiture. The wounds were slight and had already begun to heal—and, besides, the Norsemen were inured to unbelievable physical discomforts. Nor was the thought of death what made him writhe and curse. It was the reflection that Rognor was going to take Tarala for his unwilling bride and that he, Hakon, was unable to prevent it. . . .

He froze as a light, wary step sounded outside. Then he heard a voice say, with an alien accent: “Rognor desires me to talk with the prisoner.”

“How do I know you speak truth?” grumbled the guard.

“Go and ask Rognor; I will stand guard while you go. If he flays your back for disturbing him, don’t blame me.”

“Go in, in the name of Loki,” snarled the guard. “But do not tarry too long.”

There was a fumbling of bolts and bars; the door swung open, framing a tall, lithe form; then it closed again.

Cormac Mac Art looked down at the prostrate Hakon. Cormac was fully armed, and on his head he wore a helmet with a crest ornamented with flowing horse hair. This seemed to make him inhumanly tall and, in the flickering, illusive light which heightened the darkness and sinisterness of his appearance, the Gaelic pirate seemed not unlike some sombre demon come to taunt a captive in a shadowy corner of Hell.

“I thought you would come,” said Hakon, rising to a sitting position. “Speak softly, however, lest the guard outside hear us.”

“I came because I wished to know where you learned my language,” said the Gael.

“You lie,” replied Hakon cheerfully. “You came lest I betray you to Rognor. When I spoke the name men have given you, in your own tongue, you knew that I knew who you really were. For that name means ‘Wolf’ in your language, and you are not only Cormac Mac Art of Erin, but you are Cormac the Wolf, a reiver and a killer, and the right-hand man of Wulfhere the Dane, Rognor’s greatest enemy. What you are doing here I know not, but I do know that the presence of Wulfhere’s closest comrade means no good for Rognor. I have but to say a word to the guard and your fate is as certain as mine.”

Cormac looked down at the youth and was silent for a moment.

“I might cut your throat before you could speak,” he said.

“You might,” agreed Hakon, “but you won’t. It is not in you to slay a defenseless man thus.”

Cormac grinned bleakly. “True. What would you have of me?”

“My life for yours. Get me free and I keep your secret till Ragnarok.”

Cormac seated himself on a small stool and meditated.

“What are your plans?”

“Free me—and let me get my hands on a sword. I’ll steal Tarala and we will seek to gain the hills. If not, I’ll take Rognor with me to Valhalla.”

“And if you gain the hills?”

“I have men waiting there—fifteen of my closest friends, Jutes, mainly, who have no love for Rognor. On the other side of the island we have hidden a longboat. In it we can win to another island where we can hide from Rognor until we have a band of our own. Masterless men and runaway carles will come to us and it may not be long until I can burn Rognor’s skalli over his head and pay him back for his kicks.”

Cormac nodded. In that day of pirates and raiders, outlaws and reivers, such a thing as Hakon suggested was common enough.

“But first you must escape from this cell.”

“That is your part,” rejoined the youth.

“Wait,” said the Gael. “You say you have fifteen friends in the forest—”

“Aye—on pretext of a wolf hunt we went up into the hills yesterday and I left them at a certain spot, while I slipped back and made the rest of my plans with Tarala. I was to spend the day at the skalli, and then, pretending to go for my friends tonight, I was to ride forth, returning stealthily and stealing Tarala. I reckoned not on Anzace, that Byzantium he-witch, whose foul heart, I swear, I will give to the kites—”

“Enough,” snapped Cormac impatiently. “Have you any friends among the carles now in the steading? Methought I noted some displeasure among them at your rough handling.”

“I have a number of friends and half-friends,” answered Hakon, “but they waver—a carle is a stupid animal and apt to follow whoever seems strongest. Let Rognor fall, with his band of chosen henchmen, and the rest would likely as not join my forces.”

“Good enough.” Cormac’s eyes glittered as his keen brain began racing with an idea. “Now, listen—I told Rognor truth when I said my galley was dashed on the rocks last night—but I lied when I said only I escaped. Well hidden beyond the southern point of this island, where the sand spits run out into the surf, is Wulfhere with fifty-odd swordsmen. When we fought through the madness of the breakers last night and found ourselves ashore with no ship and only a part of our band left alive—and on Rognor’s island—we took council and decided that I, whom Rognor was less likely to know, should go boldly up to his skalli and, getting into his favor, look for a chance to outwit him and seize one of his galleys. For it is a ship we want. Now I will bargain with you. If I help you to escape, will you join your forces with mine and Wulfhere’s and aid us to overthrow Rognor? And, having overthrown him, will you give us one of his long ships? That is all we ask. The loot of the skalli and all Rognor’s carles and the rest of his ships shall be all yours. With a good long ship under our feet, Wulfhere and I will soon gain plunder enough—aye, and Vikings for a full crew.”

“It is a bargain,” promised the youth. “Aid me and I aid you; make me lord of this island with your help and you shall have the pick of the long ships.”

“Good enough; now attend me. Is your guard likely to be changed tonight?”

“Scarcely, I think.”

“Think you he could be bribed, Hakon?”

“Not he. He is one of Rognor’s picked band.”

“Well, then we must try some other way. If we can dispose of him, your escape will hardly be discovered before morning. Wait!”

The Gael stepped to the door of the cell and spoke to the guard.

“What sort of a watchman are you, to leave a way of escape for your prisoner?”

“What mean you?” The Viking’s beard bristled.

“Why, all the bars have been torn from the window.”

“You are mad!” growled the warrior, entering the cell. He raised his head to stare at the window, and even as his chin rose at an angle following his eyes, Cormac’s iron fist, backed by every ounce of his mighty body, crashed against the Viking’s jaw. The fellow dropped like a slaughtered ox, senseless.

The key to Hakon’s chains were at the guard’s girdle. In an instant the young Viking rose, free of his bonds, and Cormac, having gagged the unconscious warrior and chained him in turn, handed it to Hakon who grasped it eagerly. No word was said as the two stole from the cell and into the shadows of the surrounding trees. There Cormac halted. He eyed the steading keenly. There was no moon but the starlight was sufficient for the Gael’s purposes.

The skalli, a long rambling structure of logs, faced the bay where Rognor’s galleys rode at anchor. Grouped about the main building in a rough half circle were the store houses, the huts of the carles and the stables. A hundred or so yards separated the nearest of these from the skalli, and the hut wherein Hakon had been pent was the furthest away from the hall. The forest pressed closely on three sides, the tall trees overshadowing many of the store houses. There was no wall or moat about Rognor’s steading. He was sole lord of the island and expected no raid from the land side. At any rate, his steading was not intended as a fortress but as a sort of camp from which he swooped down on his victims.

While Cormac was taking in all salient points, his quick ears caught a stealthy footstep. Straining his eyes, he glimpsed the hint of a movement under the thick trees. Beckoning Hakon, he crept silently forward, dirk in hand. The brooding shadows masked all, but Cormac’s wild beast instinct, that comes to men who live by their wits, told him that someone or something was gliding through the darkness close at hand. A twig snapped faintly some little distance away, and then, a moment later, he saw a vague shape detach itself from the blackness of the trees and drift swiftly toward the skalli. Even in the dimness of the starlight the creature seemed abnormal and uncanny.

“Anzace!” hissed Hakon, electrified. “He was hiding in the trees, watching the cell! Stop him, quickly!”

Cormac’s grip on his arm stayed him from springing out recklessly in pursuit.

“Silence!” hissed the Gael. “He knows you are free, but he may not know we know it. We have yet time before he reaches Rognor.”

“But Tarala!” exclaimed Hakon fiercely. “I’ll not leave her alone here now. Go if you will—I’ll steal her away now, or die here!”

Cormac glanced quickly toward the skalli. Anzace had vanished around the corner. Apparently he was making for the front entrance.

“Lead to the girl’s chamber,” growled Cormac. “It’s a desperate chance but Rognor might cut her throat when he learns we’ve fled, before we could return and rescue her.”

Hakon and his companion, emerging from the shadows, ran swiftly across the open starlit space which parted the forest from the skalli. The young Norseman led the way to a heavily barred window near the rear end of the long, rambling hall. Crouching there in the shadows of the building, he rapped cautiously on the bars, three times. Almost instantly Tarala’s white face was framed dimly in the aperture.

“Hakon!” came the passionate whisper. “Oh, be careful! Old Eadna is in the room with me. She is asleep, but—”

“Stand back,” whispered Hakon, raising his sword. “I’m going to hew these bars apart—”

“The clash of metal will wake every carle on the island,” grunted Cormac. “We have a few minutes leeway while Anzace is telling his tale to Rognor. Let you not throw it away.”

“But how else—?”

“Stand away,” growled the Gael, gripping a bar in each hand and bracing his feet and knees against the wall.

Hakon’s eyes widened as he saw Cormac arch his back and throw every ounce of his incredible frame into the effort. The young Viking saw the great muscles writhe and ripple along the Gael’s arms, shoulders and legs; the veins stood out on Cormac’s temples, and then, before the astounded eyes of the watchers the bars bent and gave way, literally torn from their sockets. A dull, rending crash resulted, and in the room someone stirred with a startled exclamation.

“Quick, through the window!” snapped Cormac fiercely, galvanized back into dynamic action in spite of the terrific strain of his feat.

Tarala flung one limb over the shattered sill—then there sounded a low, fierce exclamation behind her and a quick rush. A pair of thick, clutching hands closed on the girl’s shoulders—and then, twisting about, Tarala struck a heavy blow. The hands went limp and there was the sound of a falling body. In another instant the British girl was out of the window and in the arms of her lover.

“There!” she gasped breathlessly, half sobbing, throwing aside the heavy wine goblet with which she had knocked her guard senseless. “That pays old Eadna back for some of the spankings she gave me!”

“Haste!” rapped Cormac, urging the pair toward the forest. “The whole steading will be roused in a moment—”

Already lights were flaring and Rognor’s bull voice was heard bellowing. In the shadows of the trees Cormac halted an instant.

“How long will it take you to reach your men in the hills and return here?”

“Return here?”

“Yes.”

“Why—an hour and a half at the utmost.”

“Good!” snapped the Gael. “Conceal your men on yonder side of the clearing and wait until you hear this signal—” And he cautiously made the sound of a night bird thrice repeated.

“Come to me—alone—when you hear that sound—and take care to avoid Rognor and his men as you come—”

“Why—he’ll most certainly wait until morning before he begins searching the island.”

Cormac laughed shortly. “Not if I know him. He’ll be out with all his men combing the woods tonight. But we’ve wasted too much time—see, the steading is a-swarm with armed warriors. Get your Jutes back here as soon as you may. I’m for Wulfhere.”

Cormac waited until the girl and her lover had vanished in the shadows, then he turned and ran fleetly and silently as the beast for which he was named. Where the average man would have floundered and blundered through the shadows, caroming into trees and tripping over bushes, Cormac sped lightly and easily, guided partly by his eyes, mainly by his unerring instinct. A lifetime in the forests and on the seas of the wild northern and eastern countries had given him the thews, wits and endurance of the fierce beasts that roamed there.

Behind him he heard shouts, clashing of arms and a bloodthirsty voice roaring threats and blasphemies. Evidently Rognor had discovered that both his birds had flown. These sounds grew fainter as he rapidly increased the distance between, and presently the Gael heard the low lapping of waves against the sand bars. As he approached the hiding-place of his allies, he slackened his pace and went more cautiously. His Danish friends lacked somewhat of his ability to see in the dark, and the Gael had no wish to stop an arrow intended for an enemy.

He halted and sounded the low pitched call of the wolf. Almost instantly came an answer, and he went forward with more assurance. Soon a vague huge figure rose in the shadows in front of him and a rough voice accosted him.

“Cormac—by Thor, we had about decided you failed to trick them—”

“They are slow witted fools,” answered the Gael. “But I know not if my plan shall succeed. We are only some seventy to over three hundred.”

“Seventy—why—?”

“We have some allies now—you know Hakon, Rognor’s mate?”

“Aye.”

“He has turned against his chief and now moves against him with fifteen Jutes—or will shortly. Come, Wulfhere, order out the warriors. We go to throw the dice of chance again. If we lose, we gain an honorable death; if we win, we gain a goodly long ship, and you—vengeance!”

“Vengeance!” murmured Wulfhere softly. His fierce eyes gleamed in the starlight and his huge hand locked like iron about the handle of his battle-axe. A red-bearded giant was the Dane, as tall as Cormac and more heavily built. He lacked something of the Gael’s tigerish litheness but he made up for that in oak-and-iron massiveness. His horned helmet increased the barbaric wildness of his appearance.

“Out of your dens, wolves!” he called into the darkness behind him. “Out! No more skulking for Wulfhere’s killers—we go to feed the ravens. Osric—Halfgar—Edric—Athelgard—Aslaf—out, wolves, the feast is ready!”

As if born from the night and the shadows of the brooding trees, the warriors silently took shape. There were few words spoken and the only sounds were the occasional rattle of a belt chain or the rasp of a swinging scabbard. Single file they trailed out behind their leaders, and Cormac, glancing back, saw only a sinuous line of great, vague forms, darker shadows amid the shadows, with a swaying of horns above. To his imaginative Celtic mind it seemed that he led a band of horned demons through the midnight forest.

At the crest of a small rise, Cormac halted so suddenly that Wulfhere, close behind, bumped into him. The Gael’s steel fingers closed on the Viking’s arm, halting his grumbled question. Ahead of them came a sudden murmer and a rattle of weapons, and now lights shone through the trees.

“Lie down!” hissed Cormac, and Wulfhere obeyed, growling the order back to the men behind. As one man, they prostrated themselves and lay silently. The noise grew louder swiftly, the tramp of many men. Presently into view came a motley horde of men, waving torches as they scanned all sides of the sullen forest, whose menacing darkness the torches but accentuated. They were following a dim trail which cut across Cormac’s line of march. In front of them strode Rognor, his face black with passion, his eyes terrible. He gnawed his beard as he strode, and his great sword trembled in his hand. Close behind him came his picked swordsmen in a compact, immobile-faced clump, and behind them the rest of the carles strung out in a straggling horde. At the sight of his enemy Wulfhere shivered as with a chill. Under Cormac’s restraining hand the great thews of his arm swelled and knotted into ridges of iron.

“A flight of arrows, Cormac,” he urged in a passionate whisper, his voice heavy with hate. “Let’s loose a rain of shafts into them and then lash in with the blades—”

“No, not now!” hissed the Gael. “There are nearly three hundred men with Rognor. He is playing into our hands and we must not lose the chance the gods have given us! Lie still and let them pass!”

Not a sound betrayed the presence of the fifty-odd Danes as they lay like the shadow of Doom above the slope. The Norsemen passed at right angles and vanished in the forest beyond without having seen or heard anything of the men whose fierce eyes watched them. Cormac nodded grimly. He had been right when he assumed that Rognor would not wait for the dawn before combing the island for his captive and her abductor. Here in this forest, where fifty-odd men could escape the eyes of the searchers, Rognor could scarcely have hoped to find the fugitives.

But the fury that burned in the Norseman’s brain would not allow him to keep still while those who defied him were still at liberty. It was not in a Viking to sit still when fired with rage, even though action were useless. Cormac knew these strange, fierce people better than they knew themselves.

Not until the clash of steel had died out in the forest beyond, and the torchlights had become mere fire-flies glimpsed occasionally through the trees, did Cormac give the order to advance. Then at double quick time they hastened on, until they saw more lights ahead of them, and presently, crouching beneath the tall trees at the edge of the clearing, looked out on the steading of Rognor the Red. The main skalli and many of the smaller buildings were alight but only a few warriors were seen. Evidently Rognor had taken most of his carles with him on his useless chase.

“What now, Cormac?” said Wulfhere.

“Hakon should be here,” answered Cormac.

Even as he opened his mouth to give the signal agreed upon, a carle rounded the corner of a stable close by, carrying a torch. The watchers saw him alter his leisurely pace suddenly and glance fixedly in their direction. Some motion in the deep shadows had attracted his attention.

“What cursed luck!” hissed Wulfhere. “He’s coming straight for us. Edric—lose me an arrow—”

“No,” muttered Cormac, “never kill, Wulfhere, save when it is necessary. Wait!”

The Gael faded back into the darkness like a phantom. The carle came straight for the forest edge, waving his torch slightly, curious, but evidently not suspicious. Now he was under the trees and his out-thrust fagot shone full on Wulfhere, where the huge Dane stood in grim silence, motionless as a statue.

“Rognor!” The flickering light was illusive; the carle saw only a red-bearded giant. “Back so soon? Have you caught—?”

The sentence broke off abruptly as he saw the red beards and fierce, unfamiliar faces of the silent men ranged behind Wulfhere; his gaze switched back to the chief and his eyes flared with sudden horror. His lips parted, but at that instant an iron arm hooked about his throat, strangling the threatened yell. Wulfhere knocked the torch from his hand and stamped it out, and in the darkness the carle was disarmed and bound securely with his own harness.

“Speak low and answer my questions,” sounded a sinister whisper at his ear. “How many weapon-men are there left at the steading?”

The carle was brave enough in open battle, but the suddenness of the surprise had unnerved him, and here in the darkness, surrounded by his ruthless hereditary foes, with the demonic Gael muttering at his shoulder, the Norseman’s blood turned to ice.

“Thirty men remain,” he answered.

“Where are they?”

“Half of them are in the skalli. The rest are in the huts.”

“Good enough,” grunted the Gael. “Gag him and bring him along with us. Now wait here until I find Hakon.” He gave the cry of a sleepy bird, thrice repeated, and waited a moment. The answer came drifting back from the woods on the other side of the clearing.

“Stay here,” ordered the Gael, and melted from the sight of Wulfhere and his Danes like a shadow.

Cautiously he made his way around the fringe of the forest, keeping well hidden in the trees, and presently a slight rustling noise ahead of him made him aware that a body of men lurked before him. He sounded the signal again, and presently heard Hakon whisper a sibilant warning. Behind the young Viking the Gael made out the vague forms of his warriors.

“By the gods,” muttered Cormac impatiently, “you make enough noise to wake Caesar. Surely the carles had investigated but that they thought you a herd of buffalo—who is this?”

By Hakon’s side was a slim figure, clad in mail and armed with a sword, but strangely out of place among the giant warriors.

“Tarala,” answered Hakon. “She would not stay hidden in the hills—so I found a corselet that she could wear and—”

Cormac cursed fervently. “Well—well. Now attend me closely. See you yon hut—the one wherein you were confined? Well, we are going to set fire to it.”

“But, man,” exclaimed Hakon, “the flame will bring Rognor on the run!”

“Exactly; that is what I wish. Now when the fire brings the carles running, you and your Jutes sally from the forest and fall upon them. Cut down as many as you can, but the moment they rally and make head against you, fall back into the stables, which you can easily do. If you work it right, you should do this without losing a man. Then, once inside the stable, bar and bolt the doors and hold it against them. They will not set fire to it, because many fine horses are there, and you with your men can hold it easily against thirty.”

“But what of you and your Danes?” protested Hakon. “Are we to bear all the brunt and danger, while—”

Cormac’s hand shot out and his steely fingers sank fiercely in Hakon’s shoulder.

“Do you trust me or do you not?” he snarled. “By the blood of the gods, are we to waste the night in argument? Do you not see that so long as Rognor’s men think they have only you to deal with, the surprise will be triply effective when Wulfhere strikes? Worry not—when the time comes my Danes will drink blood aplenty.”

“Well enough,” agreed Hakon, convinced by the dynamic impact of the Gael’s will, “but you must have Tarala with you, out of harm’s way for the time—”

“Never!” cried the girl, stamping her small foot. “I shall be at your side, Hakon, as long as we both live. I am the daughter of a British prince and I can wield a sword as well as any of your men!”

“Well,” Cormac grinned thinly, “easy to see who’ll be the real ruler in your family—but come, we have no time to waste. Leave her here with your men for now.”

As they glided through the shadows, Cormac repeated his plans in a low voice, and soon they stood at the point where the forest most nearly approached the hut that served as Rognor’s prison. Warily they stole from the trees and swiftly ran to the hut. A large tree stood just without the door and as they passed under it, something bumped heavily against Cormac’s face. His quick hand grasped a human foot and, looking up in surprise, he made out a vague figure swaying limply to and fro above him.

“Your jailor!” he grunted. “That was ever Rognor’s way, Hakon—when in anger, hang the first man handy. A poor custom—never kill except when necessary.”

The logs of the hut were dry, with much bark still on them. A few seconds’ work with flint and steel and a thin wisp of flame caught the shredded fibre and curled up the wall.

“Back to your men, now,” muttered Cormac, “and wait until the carles are swarming about the huts. Then hack straight through them and gain the stables.”

Hakon nodded and darted away. A few minutes more found Cormac back with his own men, who were muttering restlessly as they watched the flames eat their way up the wall of the hut. Suddenly a shout sounded from the skalli. Men came pouring out of the main hall and the huts, some fully armed and wide awake, some gaping and half clad as though just awakened from a sound sleep. Behind them peered the women and slaves. The men snatched buckets of water and ran for the hut and in a moment the scene was one of the usual confusion attendant to a fire. The carles jostled each other, shouted useless advice and made a vain attempt to stem the flame which now leaped roaring up through the roof and curled high in a blaze that was sure to be seen by Rognor wherever he was.

And in the midst of the turmoil there sounded a fierce medley of yells and a small, compact body of men crashed from the forest and smote the astonished carles like a thunderbolt. Hacking and hewing right and left, Hakon and his Jutes cleft their way through the bewildered Norsemen, leaving a wake of dead and dying behind them.

Wulfhere trembled with eagerness and behind him his Danes snarled and tensed like hunting dogs straining at the leash.

“How now, Cormac,” cried the Viking chief, “shall we not strike a blow? My axe is hungry!”

“Be patient, old sea-wolf,” grinned Cormac savagely. “Your axe shall drink deep; see, Hakon and his Jutes have gained the stable and shut the doors.”

It was true. The Norsemen had recovered from their surprise and prepared to turn on their attackers with all the fury that characterized their race, but before they could make any headway, Hakon and his men had disappeared inside the stable whence came the neighing and stamping of frightened horses.

This stable, built to withstand the inroads of hunger-maddened wolves and the ravages of a Baltic winter, was a natural fortress, and against its heavy panels the axes of the carles thundered in vain. The only way into the building was through the windows. The heavy wooden bars that guarded these were soon hacked away, but climbing through them in the teeth of the defenders’ swords was another. After a few disastrous attempts, the survivors drew off and consulted with each other. As Cormac had reasoned, burning the stable was out of the question because of the blooded horses within. Nor was a flight of arrows through the windows logical. All was dark inside the stable and a chance flown shaft was more likely to hit a horse than a man. Outside, however, the whole steading was lit like day by the burning hut; the Jutes were not famed as archers, but there were a few bows among Hakon’s men and these did good execution among the men outside.

At last a carle shouted: “Rognor will have seen the fire and be returning—Olaf, run you and meet him; and tell him Hakon and his Jutes are pent in the stable. We will surround the place and keep them there until Rognor gets here. Then we shall see!”

A carle set off at full speed and Cormac laughed softly to himself.

“Just what I was hoping for! The gods have been good to us this night, Wulfhere! But back—further into the shadows, lest the flames discover us.”

Then followed a tense time of waiting for all concerned—for the Jutes imprisoned in the stable, for the Norsemen lying about it, and for the unseen Danes lurking just within the forest edge. The fire burnt itself out and the flames died in smoking embers. Away in the east shone the first touch of dawn. A wind blew up from the sea and stirred the forest leaves. And through the woods echoed the tramp of many men, the clash of steel and deep angry shouts. Cormac’s nerves hummed like taut lute strings. Now was the crucial moment. If Rognor’s men passed from the forest into the clearing without seeing their hidden foes, all was well. Cormac made the Danes lie prone and, with heart in his mouth, waited.

Again came the glimmer of torches through the trees, and with a sigh of relief Cormac saw that Rognor was approaching the steading from another direction than that he had taken in leaving it. The motley horde broke cover almost opposite the point where Cormac and his men lay.

Rognor was roaring like a wild bull and swinging his two-handed sword in great arcs.

“Break down the doors!” he shouted. “Follow me—shatter the walls!”

The whole horde streamed out across the clearing, Rognor and his veterans in the lead.

Wulfhere had leaped to his feet and his Danes rose as a man behind him. The chief’s eyes were blazing with battle-lust.

“Wait!” Cormac thrust him hack. “Wait until they are pounding at the doors!”

Rognor’s Vikings crashed headlong against the stable. They bunched at the windows, stabbing and hacking at the blades that thrust from within. The clash of steel rose deafeningly, frightened horses screamed and kicked thunderously at their stalls, while the heavy doors shook to the impact of a hundred axes.

“Now!” Cormac leaped to his feet, and across the clearing swept a sudden storm of arrows. Men went down in windrows, and the rest turned bewilderedly to face this sudden and unguessed foe. The Danes were bowmen as well as swordsmen; they excelled all other nations of the North in this art. Now as they leaped from their hiding place, they loosed their shafts as they ran with unerring aim. But the Norsemen were not ready to break yet. Seeing their red-maned foes charging them, they supposed, dazedly, that a great host was upon them, but with the reckless valor of their breed they leaped to meet them.

Driving their last flight of shafts point-blank, the Danes dropped their bows and leaped into close quarters, yelling like fiends, to slash and hack with swords and axes.

They were far outnumbered, but the surprise told heavily and the unexpected arrows had taken terrific toll. Still Cormac, slashing and thrusting with reddened sword, knew that their only chance lay in a quick victory. Let the battle be drawn out and the superior numbers of the Norse must win. Hakon and his Jutes had sallied from the stable and were assailing their former mates from that side. There in the first white light of dawn was enacted a scene of fury.

Rognor, thought Cormac as he mechanically dodged an axe and ran the wielder through, must die quickly if the coup he wished for was to be brought about.

And now he saw Rognor and Wulfhere surging toward each other through the waves of battle. A Dane, thrusting savagely at the Norseman, went down with a shattered skull, and then with a thunderous yell of fury the two red-bearded giants crashed together. All the pent up ferocity of years of hatred burst into flame, and the opposing hordes halted their own fight mutually to watch their chieftains battle.

There was little to choose between them in size and strength. Rognor was armed with a great sword that he swung in both hands, while Wulfhere bore a long-shafted axe and a heavy shield. That shield was rent in twain beneath Rognor’s first incredible stroke, and tossing the fragments away, Wulfhere struck back and hewed one of the horns from the Norseman’s helmet. Rognor roared and cut terrifically at Wulfhere’s legs, but the huge Dane, with a quickness astounding in a man of his bulk, bounded high in the air, cleared the whistling blade and in mid-air chopped down at Rognor’s head. The heavy axe struck glancingly on the iron helmet, but even so Rognor went to his knees with a grunt. Then even as the Dane heaved up his axe for another stroke, Rognor was up and his mighty arms brought down his great sword in an arc that crashed full on Wulfhere’s helmet. The huge blade shivered with a tremendous crash and Wulfhere staggered, his eyes filling with blood. Like a wounded tiger he struck back with all the might of his gigantic frame, and his blind, terrible stroke cleft Rognor’s helmet and shattered the skull beneath. Both hosts cried out at the marvel of that blow as Rognor’s corpse tumbled at Wulfhere’s feet—and the next instant the blinded giant went down before a perfect storm of swords as Rognor’s picked swordsmen rushed to avenge their chief.

With a yell Cormac bounded into the press and his sword wove a web of death above the chief who, having grappled with some of his attackers, now kicked and wrestled with them on the bloody earth. The Danes surged in to aid their leaders, and about the fallen chieftains eddied a whirlpool of steel. Cormac found himself opposed to Rane, one of Rognor’s prize swordsmen, while Hakon battled with his mate, Halfgar. Cormac laughed; he had crossed swords with Rane, a lean shaggy wolf of a man, that morning and he knew all he wished to know about him. A quick parry of an overhand stroke, a dazzling feint to draw a wide lunge, and the Gael’s sword was through the Viking’s heart.

Then he turned to Hakon. The young Viking was hard pressed; Halfgar, a giant, taller than Wulfhere, towered over him, raining terrific blows upon his shield so swiftly Hakon could make no attempt to launch an offensive of his own. An unusually vicious stroke beat his helmet down over his eyes and for an instant he lost touch of his opponent’s blade. In that instant he would have died, but a slim, girlish figure leaped in front of him and took the blow on her own blade, the force of it dashing her to her knees. Up went the giant’s sword again—but at that second Cormac’s point pierced his bull throat just above the mail.

Then the Gael wheeled back, just as a powerful carle raised an axe high above the still prostrate Wulfhere. The point was Cormac’s favorite, but that he could use the edge as well he proved by splitting the carle’s skull to the chin. Then, grabbing Wulfhere’s shoulders, he hauled him off the men he was seeking to throttle and dragged him, cursing and bellowing like a bull, out of the press.

A quick glance showed him that Rognor’s veterans had fallen before the axes of the Danes, and that the rest of the Norsemen, seeing their chief fall, had renewed the fight only halfheartedly. Then what he had hoped for occurred. One of the Norsemen shouted: “The woods are full of Danes!” And the strange, inexplicable panic that sometimes seizes men gripped the carles. Shouting, they gave back and fled for the skalli in a straggling body. Wulfhere, shaking the blood out of his eyes and bellowing for his axe; would have hurled his men after them, but Cormac stopped him. His shouted commands kept the Danes from following the fugitives, who were fortified in the skalli and ready to sell their lives as dearly as only cornered men can.

Hakon, prompted by Cormac, shouted to them: “Ho, warriors, will ye listen to me?”

“We listen, Hakon,” came back a shout from the barred windows, “but keep back; mayhap we be doomed men, but many shall die with us if you seek to take the skalli.”

“I have no quarrel with you,” answered Hakon. “I look upon you as friends, though you allowed Rognor to bind and imprison me. But that is past; let it be forgotten. Rognor is dead; his picked veterans are dead and ye have no leader. The forest about the steading swarms with Danes who but await my signal. But that signal I am loath to give. They will burn the skalli and cut the throats of every man, woman and child among you. Now attend me—if you will accept me as your chieftain, and swear fealty to me, no harm will come to you.”

“What of the Danes?” came the shouted question. “Who are they that we should trust them?”

“You trust me, do you not? Have I ever broken my word?”

“No,” they admitted, “you have always kept faith.”

“Good enough. I swear to you that the Danes will not harm you. I have promised them a ship; that promise I must keep if they are to go in peace. But if you follow me on the Viking path, we can soon get another ship or build one. And one thing more—here stands beside me the girl who is to be my wife—the daughter of a British prince. She has promised me the aid of her people in all our endeavors. With friends on the British mainland we can have a source of supplies from whence we can raid the Angles and Saxons to our hearts’ content—with the aid of Tarala’s Britons we may carve us out a kingdom in Britain as Cerdic, Hengist and Horsa did. Now, speak—will you take me as your chief?”

A short silence followed in which the Vikings were evidently holding council with each other; then presently their spokesman shouted: “We agree to your wishes, O Hakon!”

Hakon laid down his notched and bloody sword and approached the skalli door emptyhanded. “And will you swear fealty to me on the bull, the fire and the sword?”

The great portals swung open, framing fierce, bearded faces. “We will swear, Hakon; our swords are yours to command.”

“And when they’ve found we’ve tricked them, they’ll turn and cut his throat and ours,” grunted Wulfhere, mopping the blood from his face.

Cormac smiled and shook his head. “They’ve sworn, they will keep faith. Are you badly wounded?”

“A trifle,” growled the giant. “A gash in the thigh and a few more on the arms and shoulders. It was the cursed blood that got in my eyes when Rognor’s sword bit through my helmet and into my scalp, as it broke. . . .”

“Your head’s harder than your helmet, Wulfhere,” laughed Cormac. “But here, we must be attending to our wounded. Some ten of our men are dead and nearly all of them slashed more or less. Also, some of the Jutes are down. But, by the gods, what a killing we have made this night!”

He indicated the stark and silent rows of arrow-feathered or sword-gashed Norsemen.

The sun, not yet in the zenith of the clear blue sky, glimmered on the white sails of a long ship as they spread and swelled to catch the wind. On the deck stood a small group of figures.

Cormac extended his hand to Hakon. “We have hunted together well this night, young sir. A few hours since you were a captive doomed to die and Wulfhere and I were hunted outlaws. Now you are lord of Ladbhan and a band of hardy Vikings, and Wulfhere and I have a staunch ship under our feet—though forsooth, the crew is rather scant. Still, that can be overcome as soon as the Danes hear that Wulfhere and Cormac Mac Art need men.

“And you—” he turned to the girl who stood beside Hakon, still clad in the mail that hung loosely on her lithe form—“you are in truth a valkyrie—a shield woman. Your sons will be kings.”

“Aye, that they will,” rumbled Wulfhere, enveloping Tarala’s slim hand with his own huge paw. “Were I a marrying man, I might cut Hakon’s throat and carry you off for myself. But now the wind is rising and my very heart quivers to feel the deck rocking under my feet again. Good fortune attend you all.”

Hakon, his bride and the Norsemen attending them swung down into the boat that waited to carry them ashore. At Wulfhere’s shout, his Danes cast off; the oars began to ply and the sails filled. The watchers in the boat and on shore saw the long ship stand off.

“What now, old wolf?” roared Wulfhere, dealing Cormac a buffet between the shoulders that would have felled a horse. “Where away?—it is for you to say.”

“To the Isle of Swords, first, for a full crew,” the Gael answered, his eyes alight. “Then—” he drank in deeply the crisp strong tang of the sea-wind—“then, skoal for the Viking path again and the ends of the world!”