Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

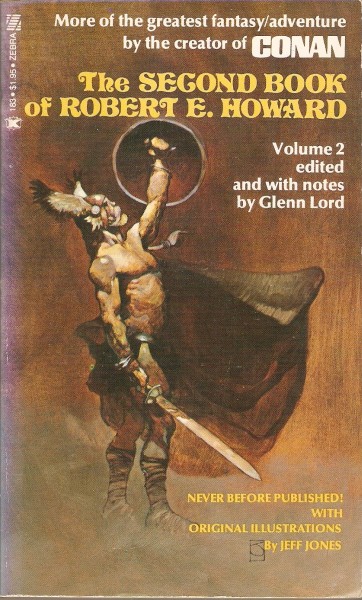

Published in The Second Book of Robert E. Howard, 1976.

(Edited version by Lin Carter first published in King Kull, 1967.)

Somewhere in the hot red darkness there began a throbbing. A pulsating cadence, soundless but vibrant with reality sent out long rippling tendrils that flowed through the breathless air. The man stirred, groped about with blind hands, and sat up. At first it seemed to him that he was floating on the even and regular waves of a black ocean, rising and falling with monotonous regularity which hurt him physically somehow.

He was aware of the pulsing and throbbing of the air and he reached out his hands as though to catch the elusive waves. But was the throbbing in the air about him, or in the brain inside his skull? He could not understand and a fantastic thought came to him—a feeling that he was locked inside his own skull.

The pulsing dwindled, centralized, and he held his aching head in his hands and tried to remember. Remember what?

“This is a strange thing,” he murmured. “Who or what am I? What place is this? What has happened and why am I here? Have I always been here?”

He rose to his feet and sought to look about him. Utter darkness met his glance. He strained his eyes, but no single gleam of light met them. He began to walk forward, haltingly, hands out before him, seeking light as instinctively as a growing plant seeks it.

“This is surely not everything,” he mused. “There must be something else—what is different from this? Light! I know—I remember Light, though I do not remember what Light is. Surely I have known a different world than this.”

Far away a faint gray light began to glow. He hastened toward it. The gleam widened, until it was as if he were striding down a long and ever widening corridor. Then he came out suddenly into dim star-light and felt the wind cold in his face.

“This is light,” he murmured, “but this is not all yet.”

He felt and recognized a sensation of terrific height. High above him, even with his eyes, and below him, flashed and blazed great stars in a majestic glittering cosmic ocean. He frowned abstractedly as he gazed at these stars.

Then he was aware that he was not alone. A tall vague shape loomed before him in the starlight. His hand shot instinctively to his left hip, then fell away limply. He was naked and no weapon hung at his side.

The shape moved nearer and he saw that it was a man, apparently a very ancient man, though the features were indistinct and illusive in the faint light.

“You are new come here?” said this figure in a clear deep voice which was much like the chiming of a jade gong. At the sound a sudden trickle of memory began in the brain of the man who heard the voice.

He rubbed his chin in a bewildered manner.

“Now I remember,” said he. “I am Kull, king of Valusia—but what am I doing here, without garments or weapons?”

“No man can bring anything through the Door with him,” said the other cryptically. “Think, Kull of Valusia, know you not how you came?”

“I was standing in the doorway of the council chamber,” said Kull dazedly, “and I remember that the watchman on the outer tower was striking the gong to denote the hour—then suddenly the crash of the gong merged into a wild and sudden flood of shattering sound. All went dark and red sparks flashed for an instant before my eyes. Then I awoke in a cavern or a corridor of some sort, remembering nothing.”

“You passed through the Door; it always seems dark.”

“Then I am dead? By Valka, some enemy must have been lurking among the columns of the palace and struck me down as I was speaking with Brule, the Pictish warrior.”

“I have not said you were dead,” answered the dim figure. “Mayhap the Door is not utterly closed. Such things have been.”

“But what place is this? Is it Paradise or Hell? This is not the world I have known since birth. And those stars—I have never seen them before. Those constellations are mightier and more fiery than I ever knew in life.”

“There are worlds beyond worlds, universes within and without universes,” said the ancient. “You are upon a different planet than that upon which you were born; you are in a different universe, doubtless in a different dimension.”

“Then I am certainly dead.”

“What is death but a traversing of eternities and a crossing of cosmic oceans? But I have not said that you are dead.”

“Then where in Valka’s name am I?” roared Kull, his short stock of patience exhausted.

“Your barbarian brain clutches at material actualities,” answered the other tranquilly. “What does it matter where you are, or whether you are dead, as you call it? You are a part of that great ocean which is Life, which washes upon all shores, and you are as much a part of it in one place as in another, and as sure to eventually flow back to the Source of it, which gave birth to all Life. As for that, you are bound to Life for all Eternity as surely as a tree, a rock, a bird or a world is bound. You call leaving your tiny planet, quitting your crude physical form—death!”

“But I still have my body.”

“I have not said that you are dead, as you name it. As for that, you may be still upon your little planet, as far as you know. Worlds within worlds, universes within universes. Things exist too small and too large for human comprehension. Each pebble on the beaches of Valusia contains countless universes within itself, and itself as a whole is as much a part of the great plan of all universes, as is the sun you know. Your universe, Kull of Valusia, may be a pebble on the shore of a mighty kingdom.

“You have broken the bounds of material limitations. You may be in a universe which goes to make up a gem on the robe you wore on Valusia’s throne or that universe you knew may be in the spiderweb which lies there on the grass near your feet. I tell you, size and space and time are relative and do not really exist.”

“Surely you are a god?” said Kull curiously.

“The mere accumulation of knowledge and the acquiring of wisdom does not make a god,” answered the other rather impatiently. “Look!” A shadowy hand pointed toward the great blazing gems which were the stars.

Kull looked and saw that they were changing swiftly. A constant weaving, an incessant changing of design and pattern was taking place.

“The ‘everlasting’ stars change in their own time, as swiftly as the races of men rise and fade. Even as we watch, upon those which are planets, beings are rising from the slime of the primeval, are climbing up the long slow roads to culture and wisdom, and are being destroyed with their dying worlds. All life and a part of life. To them it seems billions of years; to us, but a moment. All life.”

Kull watched, fascinated, as huge stars and mighty constellations blazed and waned and faded, while others equally as radiant took their places, to be in turn supplanted.

Then suddenly the hot red darkness flowed over him again, blotting out all the stars. As through a thick fog, he heard a faint familiar clashing.

Then he was on his feet, reeling. Sunlight met his eyes, the tall marble pillars and walls of a palace, the wide curtained windows through which the sunlight flowed like molten gold. He ran a swift, dazed hand over his body, feeling his garments and the sword at his side. He was bloody; a red stream trickled down his temple from a shallow cut. But most of the blood on his limbs and clothing was not his. At his feet in a horrid crimson wallow lay what had been a man. The clashing he had heard ceased, re-echoing.

“Brule! What is this? What happened? Where have I been?”

“You had nearly been on a journey to old King Death’s realms,” answered the Pict with a mirthless grin as he cleansed his sword. “That spy was lying in wait behind a column and was on you like a leopard as you turned to speak to me in the doorway. Whoever plotted your death must have had great power to so send a man to his certain doom. Had not the sword turned in his hand and struck glancingly instead of straight, you had gone before him with a cleft skull, instead of standing here now mulling over a mere flesh wound.”

“But surely,” said Kull, “that was hours agone.”

Brule laughed.

“You are still mazed, lord king. From the time he leaped and you fell, to the time I slashed the heart out of him, a man could not have counted the fingers of one hand. And during the time you were lying in his blood and yours on the floor, no more than twice that time elapsed. See, Tu has not yet arrived with bandages and he scurried for them the moment you went down.”

“Aye, you are right,” answered Kull. “I cannot understand—but just before I was struck down I heard the gong sounding the hour, and it was still sounding when I came to myself.

“Brule, there is no such thing as time nor space; for I have travelled the longest journey of my life, and have lived countless millions of years during the striking of the gong.”