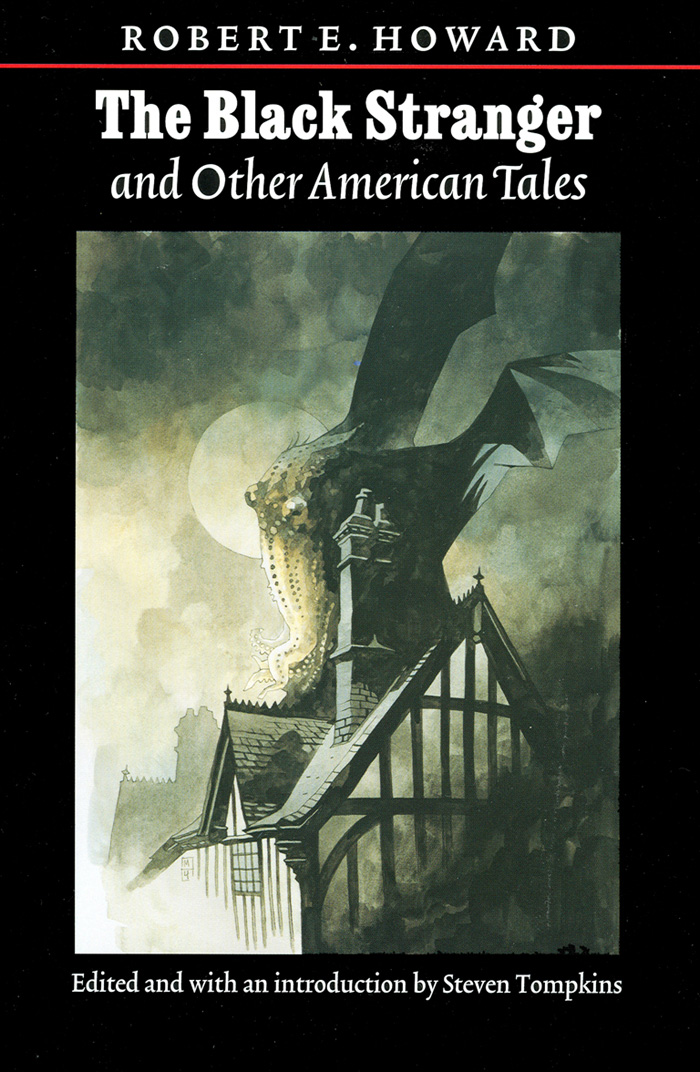

Cover from the collection The Black Stranger and Other American Tales (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The West, September 1967,

though here taken from the 2005 collection The Black Stranger and Other American Tales.

Even amid the stark realities of frontier life, the fantastic and unexplainable had its place. There was no event stranger than the case of the man whose scalped and bloody head came thrice to a woman in a dream.

One early morning in autumn, 1833, five men were cooking their breakfast of venison over a campfire on the banks of a stream some miles south of what is now the city of Austin, Texas. They were Josiah Wilbarger, Thomas Christian, Maynie, William Strother, and Standifer. They had been out on a land prospecting trip and were returning to the settlements. Wilbarger’s cabin was on the Colorado River, near the present site of Bastrop, and only one family—the Hornsbys—lived above him.

As the party busied themselves over their meal, there came a sudden interruption—common enough in those perilous days.

From the surrounding thickets and trees crashed a volley of shots, a whistling flight of arrows. Unseen, the red-skinned painted warriors had stolen up and trapped their prey. Three of the men dropped, riddled. The other two, miraculously untouched by the missiles whistling about them, sprang to their horses, broke through the ambush and out-ran their attackers. Looking back as they rode, they saw the bodies of their three companions lying motionless in pools of blood. One of these was Wilbarger, and they plainly saw the feathered end of an arrow standing up from his body.

They drove in the spurs and raced madly through the thickets, striving to shut out from their horrified ears the triumphant and fiendish yells of their barbaric attackers.

These had not long pursued the fleeing survivors; they returned to the bodies which lay by the small fire which still burned cheerfully, lighting that scene of horror. They gathered about, those lean, naked men, hideously painted, with shaven heads, and bearing tomahawks in their beaded girdles. They stripped the bodies and then, as a hunter might strip the pelt from a trapped animal, they took the symbols of their victory—the scalps of their victims.

This horrible practice, which the English settlers first introduced to the red man, and which did not originate with him, varied with different tribes. Some only took a small part of the scalp. Some ripped off the entire scalp. The braves who had surprised the land prospectors took the whole scalp. Josiah Wilbarger, struck once by an arrow and twice by bullets, was not dead, though he lay like a lifeless corpse. He was only semi-conscious, dimly aware of what was going on about him. He felt rude hands ripping the clothing from his body, and he saw, as in a dream, the gory scalps ripped from the heads of his dead companions. Then he felt a lean muscled hand locked in his own hair, pulling back his head at an agonizing angle. It is fantastic that he could have so feigned death as to fool the keen hunters in whose hands he lay.

He realized the horror of his position, but he lay like a man struck dumb and paralyzed. He felt the keen edge of the scalping knife slice through his skin, and perhaps he would have cried out, but he could not. He felt the knife circle his head above the ears, though he experienced only a vague stinging. Then his head was almost wrenched from his body as his tormentor ripped the scalp away with ferocious force. Still he felt no unusual agony, numbed as he was by his desperate wounds, but the noise of the scalp leaving his head sounded in his ears like a clap of thunder. And his remaining shred of consciousness was blanked out.

Had he been capable of any distinct thought, as he sank into senselessness, it must have been that this, at last, was death. Yet again he opened his eyes upon the bloody scene and the naked, scalped corpses about the dead ashes of the fire—how much later he had no interest in even speculating about. Now all was silent and deserted; the red slayers had gone as silently and swiftly as they had come.

And in this wounded and mutilated man awoke dimly the instinct to live, so powerful in the men of the raw frontier. He began to crawl, slowly, painfully, toward the direction of the settlements. To seek to depict the agonies of that ghastly journey would be but to display the frailty of the mere written word. Flies hung in clouds over his bloody head and he left red smears on the ground and the rocks. A quarter of a mile he dragged himself, then even his steely frame rebelled, and he reposed unconscious beneath a giant post-oak tree.

Now the occult element enters into the tale. The survivors of the massacre had ridden through the wide-flung settlements, bearing the tale of the crime. They had passed the cabin of the Hornsbys, which was the only cabin on the river above that of Josiah Wilbarger.

The following night, Mrs. Hornsby lay sleeping and she dreamed. The tale of the massacre was in her mind, and it is not strange that she dreamed of her neighbor, Josiah Wilbarger. Not strange, even, that in her dream she saw him naked and scalped, since the survivors had told her he had been killed, and she was familiar with Indian customs. But what was strange is that, in her dream, she saw him, not at the camping place, but beneath a great post-oak tree, some distance from where he was struck down—and alive.

Awakened by the terror of the nightmare, she told her husband, who soothed her and told her to go back to sleep.

Again she slept, again she dreamed and again she saw Wilbarger, naked, wounded and scalped—but living—under the oak tree. Once again she awoke, and again her husband soothed her distress, and again she slept. But when she dreamed the same dream for the third time she refused any longer to doubt. She began assembling things that might be needed to bandage the wounds of a wounded man, and her vehemence convinced her husband, who gathered a party and set out. First they went to the place where the attack had occurred: they saw the two dead men there and the track Wilbarger had made in dragging his wounded body away. And beneath the great post-oak tree, they found Wilbarger, alive—but just barely!

Josiah Wilbarger lived twelve years thereafter, but his wounds never fully healed, and at last he met his death—by a dream. In a nightmare he again experienced the horror of his scalping, and leaping up, struck his head with terrific force against the bedpost. This blow, coupled with his other wounds, finally caused his death.

Marking the spot where Josiah Pugh Wilbarger of Austin’s Colony was stabbed and scalped by the Indians, is a marker placed there by the State of Texas, in 1936, which explains that while Wilbarger was attacked and scalped in 1833, he died on April 11, 1845.

A footnote to the story has it that Wilbarger told his rescuers that he had seen, in a vision, his sister Margaret, at the time when he was sure he would bleed to death without help. She urged him not to give up, that help was on the way, and that he would be found—friends would find him. Three months later, it was learned that about the time Wilbarger had this visitation, and as nearly as they could figure out at the same hour—Margaret died in her home in Missouri.

The chronicles of the Middle Ages can offer no stranger tale, yet its truth is well substantiated, and it is, perhaps the most unexplainable event in Texas history.