Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

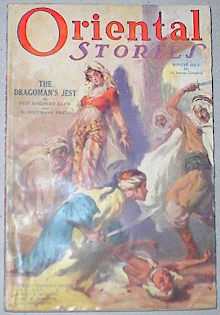

Published in Oriental Stories, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Winter 1932).

| Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 |

Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 |

Iron winds and ruin and flame.

And a Horseman shaking with giant mirth;

Over the corpse-strewn, blackened earth

Death, stalking naked, came

Like a storm-cloud shattering the ships;

Yet the Rider seated high.

Paled at the smile on a dead king’s lips.

As the tall white horse went by.

“The Ballad of Baibars.”

The idlers in the tavern glanced up at the figure framed in the doorway. It was a tall broad man who stood there, with the torch-lit shadows and the clamor of the bazaars at his back. His garments were simple tunic, and short breeches of leather; a camel’s-hair mantle hung from his broad shoulders and sandals were on his feet. But belying the garb of the peaceful traveler, a short straight stabbing sword hung at his girdle. One massive arm, ridged with muscles, was outstretched, the brawny hand gripping a pilgrim’s staff, as the man stood, powerful legs wide braced, in the doorway. His bare legs were hairy, knotted like tree trunks. His coarse red locks were confined by a single band of blue cloth, and from his square dark face, his strange blue eyes blazed with a kind of reckless and wayward mirth, reflected by the half-smile that curved his thin lips.

His glance passed over the hawk-faced seafarers and ragged loungers who brewed tea and squabbled endlessly, to rest on a man who sat apart at a rough-hewn table, with a wine pitcher. Such a man the watcher in the door had never seen—tall, deep chested, broad shouldered, built with the dangerous suppleness of a panther. His eyes were as cold as blue ice, set off by a mane of golden hair tinted with red; so to the man in the doorway that hair seemed like burning gold. The man at the table wore a light shirt of silvered mail, a long lean sword hung at his hip, and on the bench beside him lay a kite-shaped shield and a light helmet.

The man in the guise of a traveler strode purposefully forward and halted, hands resting on the table across which he smiled mockingly at the other, and spoke in a tongue strange to the seated man, newly come to the East.

The one turned to an idler and asked in Norman French: “What does the infidel say?”

“I said,” replied the traveler in the same tongue, “that a man can not even enter an Egyptian inn these days without finding some dog of a Christian under his feet.”

As the traveler had spoken the other had risen, and now the speaker dropped his hand to his sword. Scintillant lights flickered in the other’s eyes and he moved like a flash of summer lightning. His left hand darted out to lock in the breast of the traveler’s tunic, and in his right hand the long sword flashed out. The traveler was caught flat-footed, his sword half clear of its sheath. But the faint smile did not leave his lips and he stared almost childishly at the blade that flickered before his eyes, as if fascinated by its dazzling.

“Heathen dog,” snarled the swordsman, and his voice was like the slash of a blade through fabric, “I’ll send you to Hell unshriven!”

“What panther whelped you that you move as a cat strikes?” responded the other curiously, as calmly as if his life were not weighing in the balance. “But you took me by surprize. I did not know that a Frank dare draw sword in Damietta.”

The Frank glared at him moodily; the wine he had drunk showed in the dangerous gleams that played in his eyes where lights and shadows continuously danced and shifted.

“Who are you?” he demanded.

“Haroun the Traveler,” the other grinned. “Put up your steel. I crave pardon for my gibing words. It seems there are Franks of the old breed yet.”

With a change of mood the Frank thrust his sword back into its sheath with an impatient clash. Turning back to his bench he indicated table and wine pitcher with a sweeping gesture.

“Sit and refresh yourself; if you are a traveler, you have a tale to tell.”

Haroun did not at once comply. His gaze swept the inn and he beckoned the innkeeper, who came grudgingly forward. As he approached the Traveler, the innkeeper suddenly shrank back with a low half-stifled cry. Haroun’s eyes went suddenly merciless and he said, “What then, host, do you see in me a man you have known aforetime, perchance?”

His voice was like the purr of a hunting tiger and the wretched innkeeper shivered as with an ague, his dilated eyes fixed on the broad, corded hand that stroked the hilt of the stabbing-sword.

“No, no, master,” he mouthed. “By Allah, I know you not—I never saw you before—and Allah grant I never see you again,” he added mentally.

“Then tell me what does this Frank here, in mail and wearing a sword,” ordered Haroun bruskly, in Turki. “The dog-Venetians are allowed to trade in Damietta as in Alexandria, but they pay for the privilege in humility and insult, and none dares gird on a blade here—much less lift it against a Believer.”

“He is no Venetian, good Haroun,” answered the innkeeper. “Yesterday he came ashore from a Venetian trading-galley, but he consorts not with the traders or the crew of the infidels. He strides boldly through the streets, wearing steel openly and ruffling against all who would cross him. He says he is going to Jerusalem and could not find a ship bound for any port in Palestine, so came here, intending to travel the rest of the way by land. The Believers have said he is mad, and none molests him.”

“Truly, the mad are touched by Allah and given His protection,” mused Haroun. “Yet this man is not altogether mad, I think. Bring wine, dog!”

The innkeeper ducked in a deep salaam and hastened off to do the Traveler’s bidding. The Prophet’s command against strong drink was among other orthodox precepts disobeyed in Damietta where many nations foregathered and Turk rubbed shoulders with Copt, Arab with Sudani.

Haroun seated himself opposite the Frank and took the wine goblet proffered by a servant.

“You sit in the midst of your enemies like a shah of the East, my lord,” he grinned. “By Allah, you have the bearing of a king.”

“I am a king, infidel,” growled the other; the wine he had drunk had touched him with a reckless and mocking madness.

“And where lies your kingdom, malik?” The question was not asked in mockery. Haroun had seen many broken kings drifting among the debris that floated Eastward.

“On the dark side of the moon,” answered the Frank with a wild and bitter laugh. “Among the ruins of all the unborn or forgotten empires which etch the twilight of the lost ages. Cahal Ruadh O’Donnel, king of Ireland—the name means naught to you, Haroun of the East, and naught to the land which was my birthright. They who were my foes sit in the high seats of power, they who were my vassals lie cold and still, the bats haunt my shattered castles, and already the name of Red Cahal is dim in the memories of men. So—fill up my goblet, slave!”

“You have the soul of a warrior, malik. Was it treachery overcame you?”

“Aye, treachery,” swore Cahal, “and the wiles of a woman who coiled about my soul until I was as one blind—to be cast out at the end like a broken pawn. Aye, the Lady Elinor de Courcey, with her black hair like midnight shadows on Lough Derg, and the gray eyes of her, like—” he started suddenly, like a man waking from a trance, and his wayward eyes blazed.

“Saints and devils!” he roared. “Who are you that I should spill out my soul to? The wine has betrayed me and loosened my tongue, but I—” He reached for his sword but Haroun laughed.

“I’ve done you no harm, malik. Turn this murderous spirit of yours into another channel. By Erlik, I’ll give you a test to cool your blood!”

Rising, he caught up a javelin lying beside a drunken soldier, and striding around the table, his eyes recklessly alight, he extended his massive arm, gripping the shaft close to the middle, point upward.

“Grip the shaft, malik,” he laughed. “In all my days I have met no one who was man enough to twist a stave out of my hand.”

Cahal rose and gripped the shaft so that his clenched fingers almost touched those of Haroun. Then, legs braced wide, arms bent at the elbow, each man exerted his full strength against the other. They were well matched; Cahal was a trifle taller, Haroun thicker of body. It was bear opposed to tiger. Like two statues they stood straining, neither yielding an inch, the javelin almost motionless under the equal forces. Then, with a sudden rending snap, the tough wood gave way and each man staggered, holding half the shaft, which had parted under the terrific strain.

“Hai!” shouted Haroun, his eyes sparkling; then they dulled with sudden doubt.

“By Allah, malik,” said he, “this is an ill thing! Of two men, one should be master of the other, lest both come to a bad end. Yet this signifies that neither of us will ever yield to the other, and in the end, each will work the other ill.”

“Sit down and drink,” answered the Gael, tossing aside the broken shaft and reaching for the wine goblet, his dreams of lost grandeur and his anger both apparently forgotten. “I have not been long in the East, but I knew not there were such as you among the paynim. Surely you are not one with the Egyptians, Arabs and Turks I have seen.”

“I was born far to the east, among the tents of the Golden Horde, on the steppes of High Asia,” said Haroun, his mood changing back to joviality as he flung himself down on his bench. “Ha! I was almost a man grown before I heard of Muhammad—on whom peace! Hai, bogatyr, I have been many things! Once I was a princeling of the Tatars—son of the lord Subotai who was right hand to Genghis Khan. Once I was a slave—when the Turkomans drove a raid east and carried off youths and girls from the Horde. In the slave markets of El Kahira I was sold for three pieces of silver, by Allah, and my master gave me to the Bahairiz—the slave-soldiers—because he feared I’d strangle him. Ha! Now I am Haroun the Traveler, making pilgrimage to the holy place. But once, only a few days agone, I was man to Baibars—whom the devil fly away with!”

“Men say in the streets that this Baibars is the real ruler of Cairo,” said Cahal curiously; new to the East though he was, he had heard that name oft-repeated.

“Men lie,” responded Haroun. “The sultan rules Egypt and Shadjar ad Darr rules the sultan. Baibars is only the general of the Bahairiz—the great oaf!

“I was his man!” he shouted suddenly, with a great laugh, “to come and go at his bidding—to put him to bed—to rise with him—to sit down at meat with him—aye, and to put food and drink into his fool’s-mouth. But I have escaped him! Allah, by Allah and by Allah, I have naught to do with this great fool Baibars tonight! I am a free man and the devil may fly away with him and with the sultan, and Shadjar ad Darr and all Saladin’s empire! But I am my own man tonight!”

He pulsed with an energy that would not let him be still or silent; he seemed vibrant and joyously mad with the sheer exuberance of life and the huge mirth of living. With gargantuan laughter he smote the table thunderously with his open hand and roared: “By Allah, malik, you shall help me celebrate my escape from the great oaf Baibars—whom the devil fly away with! Away with this slop, dogs! Bring kumiss! The Nazarene lord and I intend to hold such a drinking bout as Damietta’s inns have not seen in a hundred years!”

“But my master has already emptied a full wine pitcher and is more than half drunk!” clamored the nondescript servant Cahal had picked up on the wharves—not that he cared, but whomever he served, he wished to have the best of any contest, and besides it was his Oriental instinct to intrude his say.

“So!” roared Haroun, catching up a full wine pitcher. “I will not take advantage of any man! See—I quaff this thimbleful that we may start on even terms!” And drinking deeply, he flung down the pitcher empty.

The servants of the inn brought kumiss—fermented mare’s milk, in leathern skins, bound and sealed—illegal drink, brought down by the caravans from the lands of the Turkomans, to tempt the sated palates of nobles, and to satisfy the craving of the steppesmen among the mercenaries and the Bahairiz.

Then, goblet for goblet with Haroun, Cahal quaffed the unfamiliar, whitish, acid stuff, and never had the exiled Irish prince seen such a cup-companion as this wanderer. For between enormous drafts, Haroun shook the smoke-stained rafters with giant laughter, and shouted over spicy tales that breathed the very scents of Cairo’s merry obscenity and high comedy. He sang Arab love songs that sighed with the whisper of palm leaves and the swish of silken veils, and he roared riding songs in a tongue none in the tavern understood, but which vibrated with the drum of Mongol hoofs and the clashing of swords.

The moon had set and even the clamor of Damietta had ebbed in the darkness before dawn, when Haroun staggered up and clutched reeling at the table for support. A single weary slave stood by, to pour wine. Keeper, servants and guests snored on the floor or had slipped away long before. Haroun shouted a thick-tongued war cry and yelled aloud with the sheer riotousness of his mirth. Sweat stood in beads on his face and the veins of his temples swelled and throbbed from his excesses. His wild wayward eyes danced with joyous deviltry.

“Would you were not a king, malik!” he roared, catching up a stout bludgeon. “I would show you cudgel-play! Aye, my blood is racing like a Turkoman stallion and in good sport I would fain deal strong blows on somebody’s pate, by Allah!”

“Then grip your stick, man,” answered Cahal reeling up. “Men call me fool, but no man has ever said I was backward where blows were going, be they of steel or wood!”

Upsetting the table, he gripped a leg and wrenched powerfully. There was a splintering of wood, and the rough leg came away in his iron hand.

“Here is my cudgel, wanderer!” roared the Gael. “Let the breaking of heads begin and if the Prophet loves you, he’d best fling his mantle over your skull!”

“Salaam to you, malik!” yelled Haroun. “No other king since Malik Ric would take up cudgels with a masterless wanderer!” And with giant laughter, he lunged.

The fight was necessarily short and fierce. The wine they had drunk had made eye and hand uncertain, and their feet unsteady, but it had not robbed them of their tigerish strength. Haroun struck first, as a bear strikes, and it was by luck rather than skill that Cahal partly parried the whistling blow. Even so it fell glancingly above his ear, filling his vision with a myriad sparks of light, and knocking him back against the upset table. Cahal gripped the table edge with his left hand for support and struck back so savagely and swiftly that Haroun could neither duck nor parry. Blood spattered, the cudgel splintered in Cahal’s hand and the Traveler dropped like a log, to lie motionless.

Cahal flung aside his cudgel with a motion of disgust and shook his head violently to clear it.

“Neither of us would yield to the other—well, in this I have prevailed—”

He stopped. Haroun lay sprawled serenely and a sound of placid snoring rose on the air. Cahal’s blow had laid open his scalp and felled him, but it was the incredible amount of liquor the Tatar had drunk that had caused him to lie where he had fallen. And now Cahal knew that if he did not get out into the cool night air at once, he too would fall senseless beside Haroun.

Cursing himself disgustedly, he kicked his servant awake and gathering up shield, helmet and cloak, staggered out of the inn. Great white clusters of stars hung over the flat roofs of Damietta, reflected in the black lapping waves of the river. Dogs and beggars slept in the dust of the street, and in the black shadows of the crooked alleys not even a thief stole. Cahal swung into the saddle of the horse the sleepy servant brought, and reined his way through the winding silent streets. A cold wind, forerunner of dawn, cleared away the fumes of the wine as he rode out of the tangle of alleys and bazaars. Dawn was not yet whitening the east, but the tang of dawn was in the air.

Past the flat-topped mud huts along the irrigation ditches he rode, past the wells with their long wooden sweeps and deep clumps of palms. Behind him the ancient city slumbered, shadowy, mysterious, alluring. Before him stretched the sands of the Jifar.

The Bedouins did not cut Red Cahal’s throat on the road from Damietta to Ascalon. He was preserved for a different destiny and so he rode, careless, and alone except for his ragamuffin servant, across the wastelands, and no barbed arrow or curved blade touched him, though a band of hawk-like riders in floating white khalats harried him the last part of the way and followed him like a wolf pack to the very gates of the Christian outposts.

It was a restless and unquiet land through which Red Cahal rode on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the warm spring days of that year 1243. The red-haired prince learned much that was new to him, of the land which had been but a vague haze of disconnected names and events in his mind when he started on his exiled pilgrimage. He had known that the Emperor Frederick ii had regained Jerusalem from the infidels without fighting a battle. Now he learned that the Holy City was shared with the Moslems—to whom it likewise was holy; Al Kuds, the Holy, they called it, for from thence, they said, Muhammad ascended to paradise, and there on the last day would he sit in judgment on the souls of men.

And Cahal learned that the kingdom of Outremer was but a shadow of an heroic past. In the north Bohemund vi held Antioch and Tripoli. In the south Christendom held the coast as far as Ascalon, with some inland towns such as Hebron, Bethlehem, and Ramlah. The grim castles of the Templars and of the Knights of St. John loomed like watchdogs above the land and the fierce soldier-monks wore arms day and night, ready to ride to any part of the kingdom threatened by pagan invasion. But how long could that thin line of ramparts and men along the coast stand against the growing pressure of the heathen hinterlands?

In the talk of castle and tavern, as he rode toward Jerusalem, Cahal heard again the name of Baibars. Men said the sultan of Egypt, kin of the great Saladin, was in his dotage, ruled by the girl-slave, Shadjar ad Darr, and that sharing her rule were the war-chiefs, Ae Beg the Kurd, and Baibars the Panther. This Baibars was a devil in human form, men said—a guzzler of wine and a lover of women; yet his wits were as keen as a monk’s and his prowess in battle was the subject of many songs among the Arab minstrels. A strong man, and ambitious.

He was generalissimo of the mercenaries, men said, who were the real strength of the Egyptian army—Bahairiz, some called them, others the White Slaves of the River, the memluks. This host was, in the main, composed of Turkish slaves, raised up in its ranks and trained only in the arts of war. Baibars himself had served as a common soldier in the ranks, rising to power by the sheer might of his arm. He could eat a roasted sheep at one meal, the Arab wanderers said, and though wine was forbidden the Faithful, it was well known that he had drunk all his officers under the table. He had been known to break a man’s spine in his bare hands in a moment of rage, and when he rode into battle swinging his heavy scimitar, none could stand before him.

And if this incarnate devil came up out of the South with his cutthroats, how could the lords of Outremer stand against him, without the aid that war-torn and intrigue-racked Europe had ceased to send? Spies slipped among the Franks, learning their weaknesses, and it was said that Baibars himself had gained entrance into Bohemund’s palace in the guise of a wandering teller-of-tales. He must be in league with the Evil One himself, this Egyptian chief. He loved to go among his people in disguise, it was said, and he ruthlessly slew any man who recognized him. A strange soul, full of wayward whims, yet ferocious as a tiger.

Yet it was not so much Baibars of whom the people talked, nor yet of Sultan Ismail, the Moslem lord of Damascus. There was a threat in the blue mysterious East which overshadowed both these nearer foes.

Cahal heard of a strange new terrible people, like a scourge out of the East—Mongols, or Tartars as the priests called them, swearing they were the veritable demons of Tatary, spoken of by the prophets of old. More than a score of years before they had burst like a sandstorm out of the East, trampling all in their path; Islam had crumpled before them and kings had been dashed into the dust. And as their chief, men named one Subotai, whom Haroun the traveler, Cahal remembered, had claimed as sire.

Then the horde had turned its course and the Holy Land had been spared. The Mongols had drifted back into the limbo of the unknown East with their oxtail standards, their lacquered armor, their kettledrums and terrible bows, and men had almost forgotten them. But now of late years the vultures had circled again in the East, and from time to time news had trickled down through the hills of the Kurds, of the Turkoman clans flying in shattered rout before the yak-tail banners. Suppose the unconquerable Horde should turn southward? Subotai had spared Palestine—but who knew the mind of Mangu Khan, whom the Arab wanderers named the present lord of the nomads?

So the people talked in the dreamy spring weather as Cahal rode to Jerusalem, seeking to forget the past, losing himself in the present; absorbing the spirit and traditions of the country and the people, picking up new languages with the characteristic facility of the Gael.

He journeyed to Hebron, and in the great cathedral of the Virgin at Bethlehem, knelt beside the crypt where candles burned to mark the birthplace of our fair Seigneur Christ. And he rode up to Jerusalem, with its ruined walls and its mullahs calling the muezzin within earshot of the priests chanting beside the Sepulcher. Those walls had been destroyed by the Sultan of Damascus, years before.

Beyond the Via Dolorosa he saw the slender columns of the Al Aksa portals and was told Christian hands first shaped them. He was shown mosques that had once been Christian chapels, and was told that the gilded dome above the mosque of Omar covered a gray rock which was the Muhammadan holy of holies—the rock whence the Prophet ascended to paradise. Aye, and thereon, in the days of Israel, had Abraham stood, and the Ark of the Covenant had rested, and the Temple whence Christ drove the merchants; for the Rock was the pinnacle of Mount Moriah, one of the two mountains on which Jerusalem was built. But now the Moslem Dome of the Rock hid it from Christian view, and dervishes with naked swords stood night and day to bar the way of Unbelievers; though nominally the city was in Christian hands. And Cahal realized how weak the Franks of Outremer had grown.

He rode in the hills about the Holy City and stood on the Mount of Olives where Tancred had stood, nearly a hundred and fifty years before, for his first sight of Jerusalem. And he dreamed deep dim dreams of those old days when men first rode from the West strong with faith and eager with zeal, to found a kingdom of God.

Now men cut their neighbors’ throats in the West and cried out beneath the heels of ambitious kings and greedy popes, and in their wars and crying out, forgot that thin frontier where the remnants of a fading glory clung to their slender boundaries.

Through budding spring, hot summer and dreamy autumn, Red Cahal rode—following a blind pilgrimage that led even beyond Jerusalem and whose goal he could not see or guess. Ascalon he tarried in, Tyre, Jaffa and Acre. He was visitor at the castles of the Military Orders. Walter de Brienne offered him a part in the rule of the fading kingdom, but Cahal shook his head and rode on. The throne he had never pressed had been snatched beyond his reach and no other earthly glory would suffice.

And so in the budding dream of a new spring he came to the castle of Renault d’Ibelin beyond the frontier.

The Sieur Renault was a cousin of the powerful crusading family of d’Ibelin which held its grim gray castles on the coast, but little of the fruits of conquest had fallen to him. A wanderer and adventurer, living by his wits and the edge of his sword, he had gotten more hard blows than gold. He was a tall lean man with hawk-eyes and a predatory nose. His mail was worn, his velvet cloak shabby and torn, the gems long gone from hilt of sword and dagger.

And the knight’s hold was a haunt of poverty. The dry moat which encircled the castle was filled up in many places; the outer walls were mere heaps of crumbled stone. Weeds grew rank in the courtyard and over the filled-up well.

The chambers of the castle were dusty and bare, and the great desert spiders spun their webs on the cold stones. Lizards scampered across the broken flags and the tramp of mailed feet resounded eerily in the echoing emptiness. No merry villagers bearing grain and wine thronged the barren courts, and no gayly clad pages sang among the dusty corridors. For over half a century the keep had stood deserted, until d’lbelin had ridden across the Jordan to make it a reaver’s hold. For the Sieur Renault, in the stress of poverty, had become no more than a bandit chief, raiding the caravans of the Moslems.

And now in the dim dusty tower of the crumbling hold, the knight in his shabby finery sat at wine with his guest.

“The tale of your betrayal is not entirely unknown to me, good sir,” said Renault—unbidden, for since that night of drunkenness in Damietta, Cahal had not spoken of his past. “Some word of affairs in Ireland has drifted into this isolated land. As one ruined adventurer to another, I bid you welcome. But I would like to hear the tale from your own lips.”

Cahal laughed mirthlessly and drank deeply.

“A tale soon told and best forgotten. I was a wanderer, living by my sword, robbed of my heritage before my birth. The English lords pretended to sympathize with my claim to the Irish throne. If I would aid them against the O’Neills, they would throw off their allegiance to Henry of England—would serve me as my barons. So swore William Fitzgerald and his peers. I am not an utter fool. They had not persuaded me so easily but for the Lady Elinor de Courcey, with her black hair and proud Norman eyes—who feigned love for me. Hell!

“Why draw out the tale? I fought for them—won wars for them. They tricked me and cast me aside. I went into battle for the throne with less than a thousand men. Their bones rot in the hills of Donegal and better had I died there—but my kerns bore me senseless from the field. And then my own clan cast me forth.

“I took the cross—after I cut the throat of William Fitzgerald among his own henchmen. Speak of it no more; my kingdom was clouds and moonmist. I seek forgetfulness—of lost ambition and the ghost of a dead love.”

“Stay here and raid the caravans with me,” suggested Renault.

Cahal shrugged his shoulders.

“It would not last, I fear. With but forty-five men-at-arms, you can not hold this pile of ruins long. I have seen that the old well is long choked and broken in, and the reservoirs shattered. In case of a siege you would have only the tanks you have built, filled with water you carry from the muddy spring outside the walls. They would last only a few days at most.”

“Poverty drives men to desperate deeds,” frankly admitted Renault. “Godfrey, first lord of Jerusalem, built this castle for an outpost in the days when his rule extended beyond Jordan. Saladin stormed and partly dismantled it, and since then it has housed only the bat and the jackal. I made it my lair, from whence I raid the caravans which go down to Mecca, but the plunder has been scanty enough.

“My neighbor the Shaykh Suleyman ibn Omad will inevitably wipe me out if I bide here long, though I have skirmished successfully with his riders and beat off a flying raid. He has sworn to hang my head on his tower, driven to madness by my raids on the Mecca pilgrims whom it is his obligation to protect.

“Well, I have another thing in mind. Look, I scratch a map on the table with my dagger-point. Here is this castle; here to the north is El Omad, the stronghold of the Shaykh Suleyman. Now look—far to the east I trace a wandering line—so. That is the great river Euphrates, which begins in the hills of Asia Minor and traverses the whole plain, joining at last with the Tigris and flowing into Bahr el Fars—the Persian Gulf—below Bassorah. Thus—I trace the Tigris.

“Now where I make this mark beside the river Tigris stands Mosul of the Persians. Beyond Mosul lies an unknown land of deserts and mountains, but among those mountains there is a city called Shahazar, the treasure-trove of the sultans. There the lords of the East send their gold and jewels for safekeeping, and the city is ruled by a cult of warriors sworn to safeguard the treasures. The gates are kept bolted night and day, and no caravans pass out of the city. It is a secret place of wealth and pleasure and the Moslems seek to keep word of it from Christian ears. Now it is my mind to desert this ruin and ride east in quest of that city!”

Cahal smiled in admiration of the splendid madness, but shook his head.

“If it is as well guarded as you, say, how could a handful of men hope to take it, even if they win through the hostile country which lies between?”

“Because a handful of Franks has taken it,” retorted d’Ibelin. “Nearly half a century ago the adventurer Cormac FitzGeoffrey raided Shahazar among the mountains and bore away untold plunder. What he did, another can do. Of course, it is madness; the chances are all that the Kurds will cut our throats before we ever see the banks of the Euphrates. But we will ride swiftly—and then, the Moslems may be so engaged with the Mongols, a small, hard-riding band might slip through. We will ride ahead of the news of our coming, and smite Shahazar as a whirlwind smites. Lord Cahal, shall we sit supine until Baibars comes up out of Egypt and cuts all our throats, or shall we cast the dice of chance to loot the eagle’s eyrie under the nose of Moslem and Mongol alike?”

Cahal’s cold eyes gleamed and he laughed aloud as the lurking madness in his soul responded to the madness of the proposal. His hard hand smote against the brown palm of Renault d’Ibelin.

“Doom hovers over all Outremer, and Death is no grimmer met on a mad quest than in the locked spears of battle! East we ride to the Devil knows what doom!”

The sun had scarce set when Cahal’s ragged servant, who had followed him faithfully through all his previous wanderings, stole away from the ruined walls and rode toward Jordan, flogging his shaggy pony hard. The madness of his master was no affair of his and life was sweet, even to a Cairo gutter-waif.

The first stars were blinking when Renault d’Ibelin and Red Cahal rode down the slope at the head of the men-at-arms. A hard-bitten lot these were, lean taciturn fighters, born in Outremer for the most part—a few veterans of Normandy and the Rhineland who had followed wandering lords into the Holy Land and had remained. They were well armed—clad in chain-mail shirts and steel caps, bearing kite-shaped shields. They rode fleet Arab horses and tall Turkoman steeds, and led horses followed. It was the capture of a number of fine steeds which had crystallized the idea of the raid in Renault’s mind.

D’Ibelin had long learned the lesson of the East—swift marches that went ahead of the news of the raid, and depended on the quality of the mounts. Yet he knew the whole plan was madness. Cahal and Renault rode into the unknown land and far in the east the vultures circled endlessly.

The bearded watcher on the tower above the gates of El Omad shaded his hawk-eyes. In the east a dust cloud grew and out of the cloud a black dot came flying. And the lean Arab knew it was a lone horseman, riding hard. He shouted a warning, and in an instant other lean, hawk-eyed figures were at his side, brown fingers toying with bowstring and cane-shafted spear. They watched the approaching figure with the intentness of men born to feud and raid.

“A Frank,” grunted one, “and on a dying horse.”

They watched tensely as the lone rider dipped out of sight in a dry wadi, came into view again on the near side, clattered reelingly across the dusty level and drew rein beneath the gate. A lean hand drew shaft to ear, but a word from the first watcher halted the archer. The Frank below had half-climbed, half-fallen from his reeling horse, and now he staggered to the gate and smote against it resoundingly with his mailed fist.

“By Allah and by Allah!” swore the bearded watcher in wonder. “The Nazarene is mad!” He leaned over the battlement and shouted: “Oh, dead man, what wouldst thou at the gate of El Omad?”

The Frank looked up with eyes glazed from thirst and the burning winds of the desert. His mail was white with the drifting dust, with which likewise his lips were parched and caked. He spoke with difficulty.

“Open the gates, dog, lest ill befall you!”

“It is Kizil Malik—the Red King—whom men call The Mad,” whispered an archer. “He rode with the lord Renault, the shepherds say. Hold him in play while I fetch the Shaykh.”

“Art thou weary of life, Nazarene,” called the first speaker, “that thou comest to the gate of thine enemy?”

“Fetch the lord of the castle, dog,” roared the Gael. “I parley not with menials—and my horse is dying.”

The tall lean form of Shaykh Suleyman ibn Omad loomed among the guardsmen and the old chief swore in his beard.

“By Allah, this is a trap of some sort. Nazarene, what do ye here?”

Cahal licked his blackened lips with a dry tongue.

“When the wild dogs run, panther and buffalo flee together,” he said. “Doom rushes from the east on Moslem and Christian alike. I bring you warning—call in your vassals and make fast your gates, lest another rising sun find you sleeping among the charred embers of your hold. I claim the courtesy due a perishing traveler—and my horse is dying.”

“It is no trap,” growled the Shaykh in his beard. “The Frank has a tale—there has been a harrying in the east and perchance the Mongols are upon us—open the gates, dogs, and let him in.”

Through the opened gates Cahal unsteadily led his drooping steed, and his first words gained him esteem among the Arabs.

“See to my horse,” he mumbled, and willing hands complied.

Cahal stumbled to a horse block and sank down, his head in his hands. A slave gave him a flagon of water and he drank avidly. As he set down the flagon he was aware that the Shaykh had come from the tower and stood before him. Suleyman’s keen eyes ran over the Gael from head to foot, noting the lines of weariness on his face, the dust that caked his mail, the fresh dints on helmet and shield—black dried blood was caked thick about the mouth of his scabbard, showing he had sheathed his sword without pausing to cleanse it.

“You have fought hard and fled swiftly,” concluded Suleyman aloud.

“Aye, by the Saints!" laughed the prince. “I have fled for a night and a day and a night without rest. This horse is the third which has fallen under me—”

“Whom do you flee?”

“A horde that must have ridden up from the dim limbo of Hell! Wild riders with tall fur caps and the heads of wolves on their standards.”

“Allah il Allah!” swore Suleyman. “Kharesmians!—flying before the Mongols!”

“They were apparently fleeing some greater horde,” answered Cahal. “Let me tell the tale swiftly—the Sieur Renault and I rode east with all his men, seeking the fabled city of Shahazar—”

“So that was the quest!” interrupted Suleyman. “Well, I was preparing to sweep down and stamp out that robbers’ nest when divers herdsmen brought me word that the bandits had ridden away swiftly in the night like the thieves they were. I could have ridden after, but knew that Christians riding eastward but rode to their doom—and none can alter the will of Allah.”

“Aye,” grinned Cahal wolfishly, “east to our doom we rode, like men riding blind into the teeth of a storm. We slashed our way through the lands of the Kurds and crossed the Euphrates. Beyond, far to the east, we saw smoke and flame and the wheeling of many vultures, and Renault said the Turkomans fought the Horde. But we met no fugitives and I wondered then—I wonder not now. The slayers rode over them like a wave out of the night and none was left to flee.

“Like men riding to death in a dream, we rode into the onrushing storm and the suddenness of its coming was like a thunderbolt. A sudden drum of hoofs over a ridge and they were upon us—hundreds of them, a swarm of outriders scouting ahead of the horde. There was no chance to flee—our men died where they stood.”

“And the Sieur Renault?” asked the Shaykh.

“Dead!” said Cahal. “I saw a curved blade cleave his helmet and his skull.”

“Allah be merciful and save his soul from the hellfire of unbelievers!” piously exclaimed Suleyman, who had sworn to kill the luckless adventurer on sight.

“He took toll before he fell,” grimly answered the Gael. “By God, the heathen lay like ripe grain beneath our horses’ hoofs before the last man fell. I alone hacked my way through.”

The Shaykh, grown old in warfare, visualized the scene that lay behind that simple sentence—the swarming, howling, fur-clad horsemen with their barbaric war cries, and Red Cahal riding like a wind of Death through that maelstrom of flashing blades, his sword singing in his hand as horse and rider went down before him.

“I outstripped the pursuers,” said Cahal, “and as I rode over a hill I looked back and saw the great black mass of the horde swarming like locusts over the land, filling the sky with the clamor of their kettledrums. The Turkomans had risen behind us as we had raced through their lands, and now the desert was alive with horsemen—but the whole east was aflame and the tribesmen had no time to hunt down a single rider. They were faced with a stronger foe. So I won through.

“My horse fell under me, but I stole a steed from a herd watched by a Turkoman boy. When it could do no more, I took a mount from a wandering Kurd who rode up, thinking to loot a dying traveler. And now I say to you, whom men dub the Watcher of the Trail—beware, lest these demons from the east ride over your ruins as they have ridden over the corpses of the Turkomans. I do not think they’ll lay siege—they are like wolves ranging the steppes; they strike and pass on. But they ride like the wind. They have crossed the Euphrates. Behind me last night the sky was red as blood. Hard as I have ridden, they must be close on my heels.”

“Let them come,” grimly answered the Arab. “El Omad has held out against Nazarene, Kurd and Turk—for a hundred years no foe has set foot within these walls. Malik, this is a time when Christian and Moslem should join hands. I thank you for your warning, and beg you to aid me in holding the walls.”

But Cahal shook his head.

“You will not need my help, and I have other work to do. It was not to save my worthless life that I have ridden three noble steeds to death—otherwise I had left my body beside Renault d’Ibelin. I must ride on; Jerusalem is in the path of these devils, with its ruined walls and scanty guard.”

Suleyman paled and plucked his beard.

“Al Kuds! These pagan dogs will slay Christian and Muhammadan alike, and desecrate the holy places!”

“And so,” Cahal rose stiffly, “I must on to warn them. So swiftly have these Kharesmians come that no word of their coming can have gone into Palestine. On me alone the burden of warning lies. Give me a fleet horse and let me go.”

“You can do no more,” objected Suleyman. “You are foredone—an hour more and you would drop senseless from the saddle. I will send one of my men instead—”

Cahal shook his head. “The duty is mine. Yet I will sleep an hour—one small hour can make no great difference. Then I will fare on.”

“Come to my couch,” urged Suleyman, but the hardy Gael shook his head.

“This has been my couch before,” said he, and flinging himself down on the scanty grass of the courtyard, he drew his cloak about him and fell into the deep sleep of utter exhaustion. Yet he slept but an hour when he awoke of his own accord. Food and wine were placed before him and he drank and ate ravenously. His features were still drawn and haggard, but in his short rest he had drawn upon hidden springs of endurance. An iron man in an age of iron, he added to his physical ruggedness a dynamic nerve-energy that carried him beyond himself and upheld him after more stolid men had dropped by the wayside.

As he reined out of the gates on a swift Arab steed, the watchmen shouted and pointed to the east where a pillar of smoke billowed up against the hot blue sky. The Shaykh flung up his arm in salute as Cahal rode toward Jerusalem at a swinging gallop that ate up the miles.

Bedouins in their black felt tents gaped at him; herdsmen leaning on their staves stiffened at his shout. A rising drum of hoofs, the wave of a mailed arm, a shouted warning, then the dwindling hoofbeats—behind him the frenzied people snatched up their belongings and fled shrieking to places of shelter or hiding.

The moon was setting as Cahal splashed through the calm waters of the Jordan, flecked with the mirrored stars. The sun was rising when his horse fell at the gate of Jerusalem that opens on the Damascus road. Cahal staggered up, half-dead himself, and gazing at the crumbling ruins of the shattered walls, he groaned aloud. On foot he hurried forward and a group of placid Syrians watched him curiously. A bearded Flemish man-at-arms came forward, trailing his pike. Cahal snatched a wine-flask that hung at the soldier’s girdle and emptied it at one draft.

“Lead me to the patriarch,” he gasped throatily. “Doom rides on swift hoofs to Jerusalem—ha!”

From the people a thin cry of wonder and fear had gone up—Cahal wheeled and felt fear constrict his throat. Again in the east he saw flying flame and drifting smoke—the gigantic tracks of the destroying horde.

“They have crossed the Jordan!” he cried. “Saints of God, when did men born of women ride so madly? They spurn the very wind—curst be the weakness that made me waste a single hour—”

The words died in his throat as he looked at the ruined walls. Truly, an hour more or less could have no significance in that doomed city.

Cahal hurried through the streets with the soldier, and he saw that already the word had spread like wildfire. Jews in their blue shubas ran about howling; in the streets and on the housetops women wrung their white hands and wailed. Tall Syrians bound their belongings on donkeys and formed the nucleus of a disorderly horde that streamed out of the western gates staggering under bundles of household goods. The city crouched trembling and dazed with terror under the threat rising in the east. What horde was sweeping upon them they did not know, nor care; death is death, whoever the dealer.

Some cried out that the Tartars were upon them and both Moslem and Nazarene shook. Cahal found the patriarch bewildered and helpless. With a handful of soldiers, how could he defend the wallless city? He was ready to give up his life in the vain attempt; he could do no more. The mullahs rallied their people, and for the first time in all history Moslem and Christian joined forces to defend the city that was holy to both. The great mass of the people fled into the mosques or the cathedrals, or crouched resignedly in the streets, dumbly awaiting the stroke. Men cried on Jehovah and on Allah, and some prophesied a miracle that should deliver the Holy City. But in the merciless blue sky no flaming sword appeared, only the smoke of the pillaging, the flame of the slaughter, and at last the dust clouds of the riders.

The patriarch had bunched his pitiful force of men-at-arms, knights, armed pilgrims and Moslems, at the Damascus Gate. Useless to man the ruined walls. There they would face the horde and give up their lives, without hope and without fear.

Cahal, his weariness half-forgotten in the drunkenness of anticipated battle, reined beside the patriarch on the great red stallion that had been given him, and cried out suddenly at the sight of a tall, broad man on a rangy Turkish bay.

“Haroun, by all the Saints!”

The other turned toward him and Cahal wavered. Was this Haroun? The fellow was clad in the mail shirt and peaked helmet of a Turkish soldier. On his brawny right arm he bore a round spiked buckler and at his belt hung a long broad scimitar, heavier by pounds than the average Moslem blade. Moreover, Haroun had been clean-shaven and this man wore the fierce curving mustachios of the Turk. Yet the build of him—that square dark face—those blazing blue eyes—

“By the Saints, Haroun,” said Cahal heartily, “what do you here?”

“Allah blast me if I be any Haroun,” answered the soldier in a deep growling voice. “I am Akbar the Soldier, come to Al Kuds on pilgrimage. You have mistaken me for another.”

Cahal frowned. The voice was not even that of Haroun, yet surely in all the world there was not such another pair of eyes. He shrugged his shoulders.

“Well, it is of no moment—where are you going?”

For the man had reined about.

“To the hills!” answered the soldier. “We can do no good by dying here—best come with me. From the dust, it is a whole horde that is riding upon us.”

“Flee without striking a blow? Not I!” snapped Cahal. “Go, if you fear.”

Akbar swore loudly. “By Allah and by Allah! A man had better place his head beneath an elephant’s tread than call me coward! I’ll stand my ground as long as any Nazarene!”

Cahal turned away shortly, irritated by the fellow’s manner and by his boasting. Yet for all the soldier’s wrath, it seemed to the Gael that a vagrant twinkle lighted his fierce eyes as though he shook with inward mirth. Then Cahal forgot him. A wail went up from the housetops where the helpless people watched their oncoming doom. The horde had swept into sight, up from the hazes of the Jordan’s gorge.

The skies shook with the clamor of the kettledrums; the earth trembled with the thunder of the hoofs. The headlong speed of the yelling fiends numbed the minds of their victims. From the steppes of high Asia these barbarians had fled before the Mongols like thistledown flying before the wind. Drunken with the blood of slaughtered tribes, ten thousand strong they surged on Jerusalem, where thousands of helpless folk knelt shuddering.

Cahal saw anew the hideous figures which had haunted his half-delirious dreams as he swayed in the saddle on that long flight: tall rangy steeds on which crouched the broad forms of the riders in wolfskins and mail—square dark faces, eyes glaring like mad dogs’ from beneath high fur caps or peaked helmets; standards with the heads of wolves, panthers and bears.

Headlong they swept down the Damascus road—leaping their horses over the broken walls, crowding through the ruined gates at breakneck speed—and headlong they smote the clump of defenders which spurred to meet them—smote them, broke them, shattered them, trampled them down and under, and over their mangled bodies, struck the heart of the doomed city.

Red hell reigned rampant in the streets of Jerusalem, where helpless men, women and children ran screaming before the slayers who rode them down, howling like wolves, spitting babes on their lances and holding them on high like gory standards. Under the frenzied hoofs pitiful forms fell writhing and blood flooded the gutters. Dark blood-stained hands tore the garments from shrieking girls and lance-butts shattered doors and windows behind which cowered terrified prey. All objects of worth were ripped from their places and screams of agony rose to the smoke-fouled heavens as the victims were tortured with steel and fire to make them give up their pitiful treasures. Death stalked howling through the streets of Jerusalem and men blasphemed their gods as they died.

In the first irresistible flood of that charge, such defenders as were not instantly ridden down had been torn apart and swept back in utter confusion. The weight of the impact had swept Red Cahal’s steed away as on the crest of a flood, and he found himself reining about in a narrow alley, where he had been tossed as a bit of driftwood is flung into a back-eddy by a rushing tide. He had lost sight of the patriarch and had no doubt that he lay among the trampled dead before the Damascus Gate.

His sword was red to the hilt, his soul ablaze with the battle-lust, his brain sick with fury and horror as the cries of the butchered city smote on his ears.

“I’ll leave my corpse before the Sepulcher,” he growled, and wheeling, spurred up the alley. He raced down a narrow winding street and emerged upon the Via Dolorosa just as the first Kharesmian came flying along it, scimitar dripping crimson. The red stallion’s shoulder brushed the barbarian’s stirrup and Cahal’s sword flashed like a sunburst. The Kharesmian’s head leaped from his shoulders on an arch of crimson and the Gael yelped with murderous exultation.

And now came another riding like the wind, and Cahal saw it was Akbar. The soldier reined in and shouted, “Well, good sir, are you still determined to sacrifice both our lives?”

“Your life is your own—my life is mine!” roared Cahal, eyes blazing.

He saw that a group of horsemen had ridden up to the Sepulcher from another street and were dismounting, shouting in their barbaric tongue, spattering the holy stones with blood-drops from their blades. In a red mist of fury Cahal smote them as an avalanche smites the pines. His whistling sword cleft buckler and helmet, severing necks and splitting skulls; under the hammering hoofs of his screaming charger, men rolled with smashed heads. And even in his madness Cahal was aware that he was not alone. Akbar had charged after him; his great voice roared above the clamor and the heavy scimitar in his left hand crashed through mail and flesh and bone.

The men before the Sepulcher lay in a silent gory heap when Cahal reined back and shook the bloody mist from his eyes. Akbar roared in a strange tongue and smote him thunderously on the shoulders.

“Bodga, bogatyr!” he roared, his eyes dancing, and no longer Cahal doubted that he was Haroun. “You fight like a hero, by Erlik! But come, malik—you have offered a noble sacrifice to your God and He’ll hardly blame you for saving yourself now. Thunder of Allah, man, we can not fight ten thousand!”

“Ride on,” answered Cahal, shaking the red drops from his blade. “Here I die.”

“Well,” laughed Akbar, “if you wish to throw away your life here where it will do no good—that’s your affair! The heathen may thank you, but your brothers scarcely will, when the raiders smite them suddenly! The horsemen are all dead or hemmed in the alleys. Only you and I escaped that charge. Who will carry the news of the raid to the Frankish barons?”

“You speak truth,” said Cahal shortly. “Let us go.”

The pair wheeled away and galloped down the street just as a howling horde came flying up the other end. Beyond the shattered walls Cahal looked back to see a mounting flame. He hid his face in his hands.

“Wounds of God!” he groaned. “They are burning the Sepulcher!”

“And defiling the Al Aksa mosque too, I doubt not,” said Akbar tranquilly. “Well, that which is written will come to pass, and no man may escape his fate. All things pass away, yes, even the Holy of Holies.”

Cahal shook his head, soul-sick. They rode through toiling bands of fugitives who screamed and caught at their stirrups, but Cahal steeled his heart. If he was to bear warning to the barons, he could not be burdened by helpless ones.

The roar of pillage and slaughter faded into the distance; only the smoke stood up among the hills, mute witness of the horror. Akbar laughed gustily.

“By Allah!” he swore, smiting his saddlebow, “these Kharesmians are woundy fighters! They ride like Tatars and slay like Turks! Right well would I lead them into battle! I had rather fight beside them than against them.”

Cahal made no reply. His strange companion seemed to him like a faun, a soulless fantastic being full of titanic laughter at all human things—a creature outside the boundaries of men’s dreams and reverences.

Akbar spoke abruptly. “Here our roads part for a space, malik; your road lies to Ascalon—mine to El Kahira.”

“Why to Cairo, Akbar, or Haroun, or whatever your name is?” asked Cahal.

“Because I have business with that great oaf, Baibars, whom the devil fly away with!” yelled Akbar, and his shout of laughter floated back above the hoof-beats.

It was hours later when Cahal, pushing his horse as hard as he dared, met the travelers—a slender knight in full mail and vizored helmet, with a single attendant, a big carle with a rough red beard, who wore a horned helmet and a shirt of scale-mail and bore a heavy ax. Something slumbering stirred in Cahal as he looked on that fierce bluff face, and he reined in.

“Man, where have I seen you before?”

The fierce frosty eyes met him levelly.

“By Odin, that I can’t say. I’m Wulfgar the Dane and this is my master.”

Cahal glanced at the silent knight with his plain shield. Through the bars of the vizor, shadowed eyes looked at him—great God! A shock went through Cahal, leaving him bewildered and shaken with a thousand racing chaotic thoughts. He leaned forward, striving to peer through the lowered vizor, and the knight drew back with an almost womanish gesture of rebuke. Cahal reddened.

“I crave your pardon, sir,” he said. “I did not intend this seeming rudeness.”

“My master has taken a vow not to speak or reveal his features until he has accomplished his penance,” broke in the rough Dane. “He is known as the Masked Knight. We journey to Jerusalem.”

Sorrowfully Cahal shook his head.

“No Christian may ride thither. The paynim from the outer steppes have swept over the walls and the Holy of Holies lies in smoking ruins.”

The Dane’s bearded mouth gaped.

“Jerusalem—taken?” he mouthed stupidly. “Why, good sir, that can not be! How would God allow his Holy City to fall into the hands of the infidels?”

“I know not,” said Cahal bitterly. “The ways of God and His infinite mercy are past my knowledge—but the streets of Jerusalem run with the blood of His people and the Sepulcher is black with the flames of the heathen.”

Perplexed, the Dane tugged at his red beard and glanced at his master, sitting image-like in the saddle.

“By Odin,” he growled, “what are we to do now?”

“There is but one thing to be done,” answered Cahal. “Ride back to Ascalon and give warning. I was going thither, but if you will do this thing, I will seek Walter de Brienne. Tell the Seneschal of Ascalon that Jerusalem has fallen to heathen Turks of the outer steppes, known as Kharesmians, who number some ten thousand men. Bid him arm for war—and let no grass grow under your horses’ hoofs in going.”

And Cahal reined aside and took the road for Jaffa.

Cahal found Walter de Brienne in Ramlah, brooding in the White Mosque over the sepulcher of Saint George. Fainting with weariness the Gael told his tale in a few stark bare words, and even they seemed to drag leaden and lifeless from his blackened lips. He was but dimly aware that men led him into a house and laid him on a couch. And there he slept the sun around.

He woke to a deserted city. Horror-stricken, the people of Ramlah had gathered up their belongings and fled along the road to Jaffa, crying that the end of the world was come. But Walter de Brienne had ridden north, leaving a single man-at-arms to bid Cahal follow him to Acre. The Gael rode through the hollow-echoing streets, feeling like a ghost in a dead city. The western gates swung idly open and a spear lay on the worn flags, as if the watch had dropped their weapons and fled in a sudden panic.

Cahal rode through the fields of date-palms and groves of figtrees hugging the shadow of the wall, and out on the plain he overtook staggering crowds of frantic folk burdened with their goods and crying with weariness and thirst. When the fugitives saw Cahal they screamed with fear to know if the slayers were upon them. He shook his head, pushing through. It seemed logical to him that the Kharesmians would sweep on to the sea, and their path might well take them by Ramlah. But as he rode he scanned the horizon behind him and saw neither smoke-rack nor dust cloud.

He left the Jaffa road with its hurrying throngs, and swung north. Already the tale had passed like wildfire from mouth to mouth. The villages were deserted as the folk thronged to the coast towns or retired into towers on the heights. Christian Outremer stood with its back to the sea, facing the onrushing menace out of the East.

Cahal rode into Acre, where the waning powers of Outremer were already gathering—hawk-eyed knights in worn mail—the barons with their wolfish men-at-arms. Sultan Ismail of Damascus had sent swift emissaries urging an alliance—which had been quickly accepted. Knights of St. John from their great grim Krak des Chevaliers, Templars with their red skull-caps and untrimmed beards rode in from all parts of the kingdom—the grim silent watchdogs of Outremer.

Survivors had drifted into Ascalon and Jaffa—lame, weary folk, a bare handful who had escaped the torch and sword and survived the hardships of the flight. They told tales of horror. Seven thousand Christians, mostly women and children, had perished in the sack of Jerusalem. The Holy Sepulcher had been blackened by flame, the altars of the city shattered, the shrines burned with fire. Moslem had suffered with Christian. The patriarch was among the fugitives—saved from death by the valor and faithfulness of a nameless Rhinelander man-at-arms, who hid a cruel wound until he said, “Yonder be the towers of Ascalon, master, and since you have no more need o’ me, I’ll lie me down and sleep, for I be sore weary.” And he died in the dust of the road.

And word came of the Kharesmian horde; they had not tarried long in the broken city, but swept on, down through the deserts of the south, to Gaza, where they lay encamped at last after their long drift. And pregnant, mysterious hints floated up from the blue web of the South, and de Brienne sent for Cahal O’Donnel.

“Good sir,” said the baron, “my spies tell me that a host of memluks is advancing from Egypt. Their object is obvious—to take possession of the city the Kharesmians left desolate. But what else? There are hints of an alliance between the memluks and the nomads. If this be the case, we may as well be shriven before we go into battle, for we can not stand against both hosts.

“The men of Damascus cry out against the Kharesmians for befouling holy places—Moslem as well as Christian—but these memluks are of Turkish blood, and who knows the mind of Baibars, their master?

“Sir Cahal, will you ride to Baibars and parley with him? You saw with your own eyes the sack of Jerusalem and can tell him the truth of how the pagans befouled Al Aksa as well as the Sepulcher. After all, he is a Moslem. At least learn if he means to join hands with these devils.

“Tomorrow, when the cohorts of Damascus come up, we advance southward to go against the foe ere he can come against us. Ride you ahead of the host as emissary under a flag of truce, with as many men as you wish.”

“Give me the flag,” said Cahal. “I’ll ride alone.”

He rode out of the camp before sunset on a palfrey, bearing the flag of peace and without his sword. Only a battle-ax hung at his saddlebow as a precaution against bandits who respected no flag, as he rode south through a half-deserted land. He guided his course by the words of the wandering Arab herdsmen who knew all things that went on in the land. And beyond Ascalon he learned that the host had crossed the Jifar and was encamped to the southeast of Gaza. The close proximity to the Kharesmians made him wary and he swung far to the east to avoid any scouts of the pagans who might be combing the countryside. He had no trust in the peace-token as a safeguard against the barbarians.

He rode, in a dreamy twilight, into the Egyptian camp which lay about a cluster of wells a bare league from Gaza. Misgivings smote him as he noted their arms, their numbers, their evident discipline. He dismounted, displaying the peace-gonfalcon and his empty sword-belt. The wild memluks in their silvered mail and heron feathers swarmed about him in sinister silence, as if minded to try their curved blades on his flesh, but they escorted him to a spacious silk pavilion in the midst of the camp.

Black slaves with wide-tipped scimitars stood ranged about the entrance and from within a great voice—strangely familiar—boomed a song.

“This is the pavilion of the amir, even Baibars the Panther, Caphar,” growled a bearded Turk, and Cahal said as haughtily as if he sat on his lost throne amid his gallaglachs, “Lead me to your lord, dog, and announce me with due respect.”

The eyes of the gaudily clad ruffian fell sullenly, and with a reluctant salaam he obeyed. Cahal strode into the silken tent and heard the memluk boom: “The lord Kizil Malik, emissary from the barons of Palestine!”

In the great pavilion a single huge candle on a lacquered table shed a golden light; the chiefs of Egypt sprawled about on silken cushions, quaffing the forbidden wine. And dominating the scene, a tall broad figure in voluminous silken trousers, satin vest, a broad cloth-of-gold girdle—without a doubt Baibars, the ogre of the South. And Cahal caught his breath—that coarse red hair—that square dark face—those blazing blue eyes—

“I bid you welcome, lord Caphar,” boomed Baibars. “What news do you bring?”

“You were Haroun the Traveler,” said Cahal slowly, “and at Jerusalem you were Akbar the Soldier.”

Baibars rocked with laughter.

“By Allah!” he roared, “I bear a scar on my head to this day as a relic of that night’s bout in Damietta! By Allah, you gave me a woundy clout!”

“You play your parts like a mummer,” said Cahal. “But what reason for these deceptions?”

“Well,” said Baibars, “I trust no spy but myself, for one thing. For another it makes life worth living. I did not lie when I told you that night in Damietta that I was celebrating my escape from Baibars. By Allah, the affairs of the world weigh heavily on Baibars’ shoulders, but Haroun the Traveler, he is a mad and merry rogue with a free mind and a roving foot. I play the mummer and escape from myself, and try to be true to each part—so long as I play it. Sit ye and drink!”

Cahal shook his head. All his carefully thought out plans of diplomacy fell away, futile as dust. He struck straight and spoke bluntly and to the point.

“A word and my task is done, Baibars,” he said. “I come to find whether you mean to join hands with the pagans who desecrated the Sepulcher—and Al Aksa.”

Baibars drank and considered, though Cahal knew well that the Tatar had already made up his mind, long before.

“Al Kuds is mine for the taking,” he said lazily. “I will cleanse the mosques—aye, by Allah, the Kharesmians shall do the work, most piously. They’ll make good Moslems. And winged war-men. With them I sow the thunder—who reaps the tempest?”

“Yet you fought against them at Jerusalem,” Cahal reminded bitterly.

“Aye,” frankly admitted the amir, “but there they would have cut my throat as quick as any Frank’s. I could not say to them: ‘Hold, dogs, I am Baibars!’ ”

Cahal bowed his lion-like head, knowing the futility of arguing.

“Then my work is done; I demand safe-conduct from your camp.”

Baibars shook his head, grinning. “Nay, malik, you are thirsty and weary. Bide here as my guest.”

Cahal’s hand moved involuntarily toward his empty girdle. Baibars was smiling but his eyes glittered between narrowed lids and the slaves about him half-drew their scimitars.

“You’d keep me prisoner despite the fact that I am an ambassador?”

“You came without invitation,” grinned Baibars. “I ask no parley. Di Zaro!”

A tall lank Venetian in black velvet stepped forward.

“Di Zaro,” said Baibars in a jesting voice, “the malik Cahal is our guest. Mount ye and ride like the devil to the host of the Franks. There say that Cahal sent you secretly. Say that the lord Cahal is twisting that great fool Baibars about his finger, and pledges to keep him aloof from the battle.”

The Venetian grinned bleakly and left the tent, avoiding Cahal’s smoldering eyes. The Gael knew that the trade-lusting Italians were often in secret league with the Moslems, but few stooped so low as this renegade.

“Well, Baibars,” said Cahal with a shrug of his shoulders, “since you must play the dog, there is naught I can do. I have no sword.”

“I’m glad of that,” responded Baibars candidly. “Come, fret not. It is but your misfortune to oppose Baibars and his destiny. Men are my tools—at the Damascus Gate I knew that those red-handed riders were steel to forge into a Moslem sword. By Allah, malik, if you could have seen me riding like the wind into Egypt—marching back across the Jifar without pausing to rest! Riding into the camp of the pagans with mullahs shouting the advantages of Islam! Convincing their wild Kuran Shah that his only safety lay in conversion and alliance!

“I do not fully trust the wolves, and have pitched my camp apart from them—but when the Franks come up, they will find our hordes joined for battle—and should be horribly surprized, if that dog di Zaro does his work well!”

“Your treachery makes me a dog in the eyes of my people,” said Cahal bitterly.

“None will call you traitor,” said Baibars serenely, “because soon all will cease to be. Relics of an outworn age, I will rid the land of them. Be at ease!”

He extended a brimming goblet and Cahal took it, sipped at it absently, and began to pace up and down the pavilion, as a man paces in worry and despair. The memluks watched him, grinning surreptitiously.

“Well,” said Baibars, “I was a Tatar prince, I was a slave, and I will be a prince again. Kuran Shah’s shaman read the stars for me—and he says that if I win the battle against the Franks, I will be sultan of Egypt!”

The amir was sure of his chiefs, thought Cahal, to thus flaunt his ambition openly. The Gael said, “The Franks care not who is sultan of Egypt.”

“Aye, but battles and the corpses of men are stairs whereby I climb to fame. Each war I win clinches my hold on power. Now the Franks stand in my path; I will brush them aside. But the shaman prophesied a strange thing—that a dead man’s sword will deal me a grievous hurt when the Franks come up against us—”

From the corner of his eye Cahal saw that his apparently aimless strides had taken him close to the table on which stood the great candle. He lifted the goblet toward his lips, then with a lightning flick of his wrist, dashed the wine onto the flame. It sputtered and went out, plunging the tent into total darkness. And simultaneously Cahal ripped a hidden dirk from under his arm and like a steel spring released, bounded toward the place where he knew Baibars sat. He catapulted into somebody in the dark and his dirk hummed and sank home. A death scream ripped the clamor and the Gael wrenched the blade free and sprang away. No time for another stroke. Men yelled and fell over each other and steel clanged wildly. Cahal’s crimsoned blade ripped a long slit in the silk of the tent-wall and he sprang into the outer starlight where men were shouting and running toward the pavilion.

Behind him a bull-like bellowing told the Gael that his blindly stabbing dirk had found some other flesh than Baibars’. He ran swiftly toward the horse-lines, leaping over taut tent-ropes, a shadow among a thousand racing figures. A mounted sentry came galloping through the confusion, firelight gleaming on his drawn scimitar. As a panther leaps Cahal sprang, landing behind the saddle. The memluk’s startled yell broke in a gurgle as the keen dirk crossed his throat.

Flinging the corpse to the earth, the Gael quieted the snorting, plunging steed and reined it away. Like the wind he rode through the swarming camp and the free air of the desert struck his face. He gave the Arab horse the rein and heard the clamor of pursuit die away behind him. Somewhere to the north lay the slowly advancing host of the Christians, and Cahal rode north. He hoped to overtake the Venetian on the road, but the other had too long a start. Men who rode for Baibars rode with a flowing rein.

The Franks were breaking camp at dawn when a Venetian rode headlong into their lines, gasping a tale of escape and flight, and demanding to see de Brienne.

Within the baron’s half-dismantled tent, di Zaro gasped: “The lord Cahal sent me, seigneur—he holds Baibars in parley. He gives his word that the memluks will not join the Kharesmians, and urges you to press forward—”

Outside a clatter of hoofs split the din—a lone rider whose flying hair was like a veil of blood against the crimson of dawn. At de Brienne’s tent the hard-checked steed slid to its haunches. Cahal leaped to the earth and rushed in like an avenging blast. Di Zaro cried out and paled, frozen by his doom—till Cahal’s dirk split his heart and the Venetian rolled, an earthen-faced corpse, to Walter de Brienne’s feet. The baron sprang up, bewildered.

“Cahal! What news, in God’s name?”

“Baibars joins arms with the pagans,” answered Cahal.

De Brienne bowed his head.

“Well—no man can ask to live forever.”

Through the drear gray dusty desert the host of Outremer crawled southward. The black and white standard of the Templars floated beside the cross of the patriarch, and the black banners of Damascus billowed in the faintly stirring air. No king led them. The Emperor Frederick claimed the kingship of Jerusalem and he skulked in Sicily, plotting against the pope. De Brienne had been chosen to lead the barons and he shared his command with Al Mansur el Haman, warlord of Damascus.

They went into camp within sight of the Moslem outposts, and all night the wind that blew up from the south throbbed with the beat of drums and the clash of cymbals. Scouts reported the movements of the Kharesmian horde, and that the memluks had joined them.

In the gray light of dawn Red Cahal came from his tent fully armed. On all sides the host was moving, striking tents and buckling armor. In the illusive light Cahal saw them moving like phantoms—the tall patriarch, shriving and blessing; the giant form of the Master of the Temple among his grim war-dogs; the heron-feathered gold helmet of Al Mansur. And he stiffened as he saw a slim mailed shape moving through the swarm, followed close by a rough figure with ax on shoulder. Bewildered, he shook his head—why did his heart pound so strangely at sight of that mysterious Masked Knight? Of whom did the slim youth remind him, and of what dim bitter memories? He felt as one plunged into a web of illusion.

And now a familiar figure fell upon Cahal and embraced him.

“By Allah!” swore Shaykh Suleyman ibn Omad, “but for thee I had slept in the ruins of my keep! They came like the wind, those dogs, but they found the gates closed, the archers on the walls—and after one assault, they passed on to easier prey! Ride with me this day, my son!”

Cahal assented, liking the lean hearty old desert hawk. And so it was in the glittering, plume-helmeted ranks of Damascus the Gael rode to battle.

In the dawn they moved forward, no more than twelve thousand men to meet the memluks and nomads—fifteen thousand warriors, not counting light-armed irregulars. In the center of the right wing the Templars held their accustomed place, in advance of the rest; five hundred grim iron men, flanked on one side by the Knights of St. John and the Teutonic Knights, some three hundred in all; and on the other by the handful of barons with the patriarch and his iron mace. The combined forces of their men-at-arms did not exceed seven thousand. The rest of the host consisted of the cavalry of Damascus, in the center of the army, and the warriors of the amir of Kerak who held the left wing—lean hawk-faced Arabs better at raiding than at fighting pitched battles.

Now the desert blackened ahead of them with the swarms of their foes, and the drums throbbed and bellowed. The warriors of Damascus sang and chanted, but the men of the Cross were silent, like men riding to a known doom. Cahal, riding beside Al Mansur and Shaykh Suleyman, let his gaze sweep down those grim gray-mailed ranks, and found that which he sought. Again his heart leaped curiously at the sight of the slim Masked Knight, riding close to the patriarch. Close at the knight’s side bobbed the horned helmet of the Dane. Cahal cursed, bewilderedly.

And now both hosts advanced, the dark swarms of the desert riders moving ahead of the ordered ranks of the memluks. The Kharesmians trotted forward in some formation, and Cahal saw the Crusaders close their ranks to meet the charge, without slackening their even pace. The wild riders struck in the rowels and the dark swarm rolled swiftly across the sands; then suddenly they shifted as a crafty swordsman shifts. Wheeling in perfect order they swept past the front of the knights and bursting into a headlong run, thundered down on the banners of Damascus.

The trick, born in the brain of Baibars, took the whole allied host by surprize. The Arabs yelled and prepared to meet the onset, but they were bewildered by the mad fury and numbing speed of that charge.

Riding like madmen the Kharesmians bent their heavy bows and shot from the saddle, and clouds of feathered shafts hummed before them. The leather bucklers and light mail of the Arabs were useless against those whistling missiles, and along the Damascus front warriors fell like ripe grain. Al Mansur was screaming commands for a countercharge, but in the teeth of that deadly blast the dazed Arabs milled helplessly, and in the midst of the confusion, the charge crashed into their lines. Cahal saw again the broad squat figures, the wild dark faces, the madly hacking scimitars—broader and heavier than the light Damascus blades. He felt again the irresistible concussion of the Kharesmian charge.

His great red stallion staggered to the impact and a whistling blade shivered on his shield. He stood up in his stirrups, slashing right and left, and felt mail-mesh part under his edge, saw headless corpses drop from their saddles. Up and down the line the blades were flashing like spray in the sun and the Damascus ranks were breaking and melting away. Man to man, the Arabs might have held fast; but dazed and outnumbered, that demoralizing rain of arrows had begun the rout that the curved swords completed.

Cahal, hurled back with the rest, vainly striving to hold his ground as he slashed and thrust, heard old Suleyman ibn Omad cursing like a fiend beside him as his scimitar wove a shining wheel of death about his head.

“Dogs and sons of dogs!” yelled the old hawk. “Had ye stood but a moment, the day had been yours! By Allah, pagan, will ye press me close?—So! Ha! Now carry your head to Hell in your hand! Ho, children, rally to me and the lord Cahal! My son, keep at my side. The fight is already lost and we must hack clear.”

Suleyman’s hawks reined in about him and Cahal, and the compact little knot of desperate men slashed through, riding down the snarling wolfish shapes that barred their path, and so rode out of the red frenzy of the melee into the open desert. The Damascus clans were in full flight, their black banners streaming ingloriously behind them. Yet there was no shame to be attached to them. That unexpected charge had simply swept them away, like a shattered dam before a torrent.

On the left wing the amir of Kerak was giving back, his ranks crumbling before the singing arrows and flying blades of tribesmen. So far the memluks had taken no part in the battle, but now they rode forward and Cahal saw the huge form of Baibars galloping into the fray, beating the howling nomads from their flying prey and reforming their straggling lines. The wolfskin-clad riders swung about and trotted across the sands, reinforced by the memluks in their silvered mail and heron-feathered helmets. So suddenly had the storm burst that before the Franks could wheel their ponderous lines to support the center, their Arab allies were broken and flying. But the men of the Cross came doggedly onward.

“Now the real death-grip,” grunted Suleyman, “with but one possible end. By Allah, my head was not made to dangle at a pagan’s saddlebow. The road to the desert is open to us—ha, my son, are you mad?”

For Cahal wheeled away, jerking his rein from the clutching hand of the protesting Shaykh. Across the corpse-littered plain he galloped toward the gray-steel ranks that swept inexorably onward. Riding hard, he swept into line just as the oliphants trumpeted for the onset. With a deep-throated roar the knights of the Cross charged to meet the onrushing hordes through a barbed and feathered cloud. Heads down, grimly facing the singing shafts that could not check them, the knights swept on in their last charge. With an earthquake shock the two hosts crashed together, and this time it was the Kharesmian horde which staggered.

The long lances of the Templars ripped their foremost line to shreds and the great chargers of the Crusaders overthrew horse and rider. Close on the heels of the warrior-monks thundered the rest of the Christian host, swords flashing. Dazed in their turn, the wild riders in their wolfskins reeled backward, howling and plying their deadly blades. But the long swords of the Europeans hacked through iron mesh and steel plate, to split skulls and bosoms. Squat corpses choked the ground under their horses’ hoofs, as deep into the heart of the disorganized horde the knights slashed, and the yells of the tribesmen changed to howls of dismay as the whole battle-mass surged backward.

And now Baibars, seeing the battle tremble in the balance, deployed swiftly, skirted the ragged edge of the melee and hurled his memluks like a thunderbolt at the back of the Crusaders. The fresh, unwearied Bahairiz struck home, and the Franks found themselves hemmed in on all sides, as the wavering Kharesmians stiffened and with a fresh resurge of confidence renewed the fight.