Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

The synopsis and the unfinished draft are from Howard’s typescript (a few typos have been corrected),

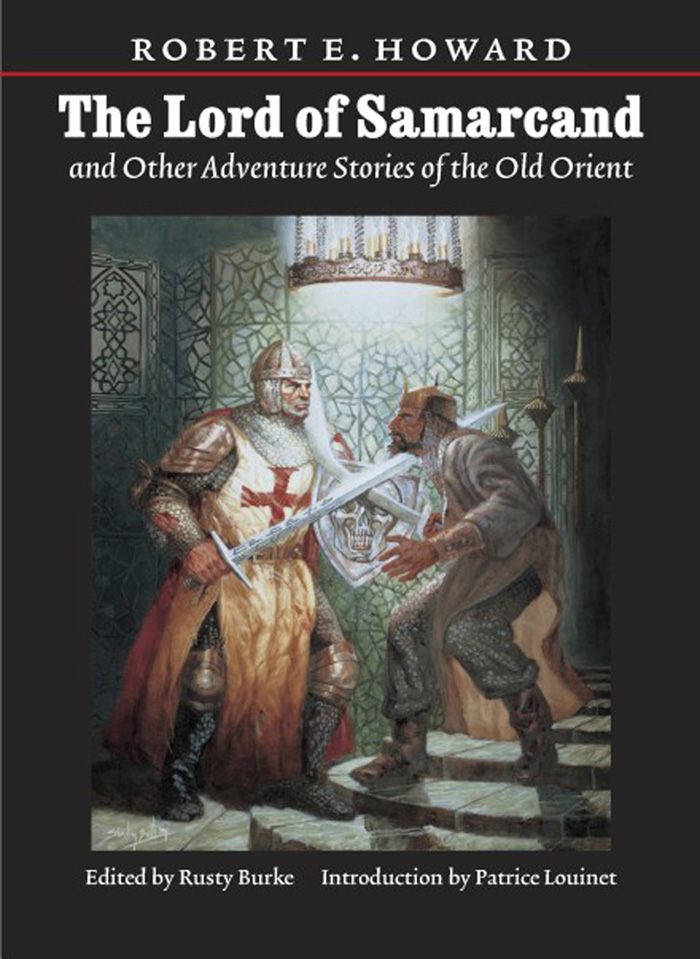

taken from The Lord of Samarcand and Other Adventure Tales of the Old Orient (University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

(The cover says “Stories” while inside it has “Tales.”)

The story, as completed by Richard Tierney, was first published in Hawks of Outremer (Donald M. Grant, 1979).

| Synopsis | Unfinished draft |

Cormac FitzGeoffrey rides into a city that the Turkomans are looting. He arrives too late to share in the loot, but he captures an Arab slave girl, Zuleika, whose owner has just been murdered by a Turkoman. He kills the Turkoman and carries her off with him, riding to the castle of Sieur Amory. There he divulges his plan. He has noticed a striking resemblance between Zuleika and the daughter of Abdullah bin Kheram, the princess Zalda, who had been carried off three years before by Kurdish raiders, on the verge of her wedding to Khelru Shah, chief of the Seljuk Turks, who rules the hill-town of Kizil-hissar, the Red Castle. Amory keeps the girl with him, and Cormac rides to Kizil-hissar. He tells Khelru Shah that he has found the vanished princess, and that he will deliver her up to him for ten thousand pieces of gold. Khelru Shah threatens to keep him as hostage, but Cormac laughs at him, telling him that if he, Cormac, has not returned in a certain time, the princess’s throat will be cut. Khelru Shah refuses to believe that the princess still lives, and decides to ride to Amory’s castle with Cormac and see for himself. They set out with three hundred riders, and even before they set forth, one Ali, an Arab trader, who has spied upon their council, races southward on a swift camel. Meanwhile Amory has become somewhat interested in his fair captive, to the extent of attempting to ravish her, but refraining for some reason he himself cannot understand. Zuleika has fallen in love with her captor, but Amory, wild, and hardened by years of intrigue and battle, cannot believe himself in love with her. Cormac and Khelru Shah ride up to the castle wall and Amory displays Zuleika on the tower. Khelru Shah is puzzled; he finally decides that it is the princess Zalda, and demands a night to think the matter over. He retires with all his force a mile away and goes into camp, while Cormac enters the castle. Just at dark, a crippled beggar howls for admission at the castle gate and is allowed to enter and sleep in the castle hall. The Arab girl is locked into her chamber with a soldier on guard and Cormac and Amory drink and converse in another chamber. The walls are closely guarded in event of a surprize attack. When all the castle is silent, the crippled beggar rises stealthily, disclosing the countenance of an Egyptian right-hand man of Khelru Shah. He steals to the girl’s chamber, strangles her guard, enters, binds and gags her, and steals out of the castle. He conceals her in the stable, then slays the soldier guarding the postern gate and opens it, then sets fire to the castle. Khelru Shah’s men, who have stolen up on foot in the darkness, rush through the postern gate. Meanwhile Cormac and Amory have quarrelled. Amory declares he will not let the girl go, and while the two are fighting hand to hand, a soldier rushes in shouting that the courtyard swarms with Turks. The handful of men in the castle cut their way out of the blazing hold, but are surrounded in the court-yard and about to be cut to pieces, when Abdullah bin Kheram rides up with a thousand men. The trader Ali has told him his daughter is captive there. Fighting ceases as all learn in wonder that Zuleika is indeed the princess Zalda. Khelru Shah is slain by Cormac who hacks his way through the Arabs and escapes, and Zalda makes known her love for Amory. The Sheikh gives his consent that they should marry and a powerful alliance is formed between the Arabs and Amory, for life.

| Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 |

Outside the clamor mounted deafeningly. The rasp of steel on steel mingled with yells of blood-lust and yells of wild triumph. The young slave girl hesitated and looked about the chamber in which she stood. There was resigned helplessness in her gaze. The city had fallen; the blood-drunk Turkomans were riding though the streets, burning, looting, slaughtering. Any moment might see the victorious savages running red handed through the house of her owner.

From another part of the house a fat merchant came running. His eyes were distended with terror, his breath came in gasps. He bore gems and worthless gew-gaws in his hands—belongings snatched blindly and at random.

“Zuleika!” his voice was the screech of a trapped weasel. “Open the door quickly, then bar it from this side—I will escape through the rear. Allah il Allah! The Turkish fiends are slaying all in the streets—the gutters run red—”

“What of me, master?” the girl asked humbly.

“What of you, hussy?” screamed the man, striking her heavily. “Open the door, open the door, I tell you—ahhhhhh!”

His voice snapped brittle as glass. Through an outer door came a wild and fearsome figure—a shaggy, ragged Turkoman whose eyes were the eyes of a mad dog. Zuleika in frozen terror saw the wide glaring eyes, the lanky hair, the short boar-spear gripped in a hand that dripped crimson.

The merchant’s voice rose in a frenzied squeaking. He made a desperate dash across the chamber but the tribesman leaped like a cat on a mouse and one lean hand gripped the merchant’s garments. Zuleika watched in dumb horror. She had reason to hate the man—reasons of outrage, punishment and indignity—but from the depths of her heart she pitied the howling wretch as he writhed and shrank from his fate. The boar-spear ripped upward; the screams broke in a fearful gurgle. The Turkoman stepped over the ghastly red thing on the floor and stalked toward the terrified girl. She shrank back, unspeaking. Lone she had learned the cruelty of men and the uselessness of appeal. She did not beg for her life. The Turkoman gripped her by the breast of the single scanty garment she wore and she felt his wild beast eyes burn into hers. He was too far gone in the slaughter-lust for her to rouse another desire in his wild soul. In that red moment she was only a living thing, pulsing and quivering with life, for him to still forever in blood and agony.

She sought to close her eyes but she could not. In a clear white light of semi-detachment she welcomed death, to end a road that had been hard and cruel. But her flesh shrank from the doom her spirit accepted and only her attacker’s grasp held her erect. Grinning like a wolf he brought the keen point of the spear against her breast and a thin trickle of blood started from the tender skin. The tribesman sucked in his breath in fierce ecstasy; he would drive the blade home slowly, gradually, twisting it excruciatingly, glutting his cruelty with the agonized writhings and screamings of his fair victim.

A heavy step sounded behind them and a rough voice swore in an unfamiliar tongue. The Turkoman wheeled, beard bristling in a ferocious snarl. The half fainting girl stumbled back against a divan, her hand to her breast. It was a mailed Frank who had entered the chamber and to the girl’s dizzy gaze he loomed like an iron clad giant. Over six feet in height he stood, and his shoulders and steel clad limbs were mighty. From his heels to his heavy vizorless helmet he was heavily armored and his sun-darkened, scarred features added to the sinister import of his appearance. There was no stain of blood on his mail and his sword hung sheathed at his girdle. The girl knew that he could be but one man—Cormac FitzGeoffrey, the Frankish outlaw who hunted at times with the Turkoman pack.

Now he strode ponderously toward them, growling a warning at the warrior, whose eyes burned with a feral light. The Turkoman spat a curse and leaped like a lean wolf, thrusting fiercely. A mail clad arm brushed the spear aside and almost with the same motion, Cormac caught the Turkoman’s throat with his left hand in a vise-like grip, and with his clenched right struck his victim a mallet-like blow on the temple. Beneath the mailed fist, the tribesman’s skull caved in like a gourd and Cormac let the twitching corpse fall carelessly at his feet. Zuleika stood silent, head bowed in submission, as resigned to this new master as to the other, but the Frank showed no signs of claiming his prey. He turned away, with a single casual glance at the girl, then stopped short as his brief gaze rested on her pale face. His eyes narrowed and he approached her. She stood before him, like a child before his overshadowing bulk.

He laid his mailed hand on her frail shoulder and her knees bent beneath the unconscious weight of it. She raised her head to look into his face. His blazing blue eyes seemed to her like those of a jungle beast.

“Girl, how are you named?” he rumbled in Arabic.

“Zuleika, master,” she answered in the same language.

He was silent, as if he pondered. His scarred face was inscrutable but she caught the new glint in his volcanic eyes. Without a word he picked her up in his left arm as a man might take up a baby. His captive voiced no protest as he carried her out into the street. Kismet. No woman knew what Fate held in store for her and Zuleika had learned submission in a bitter school.

Smoke was blown through the streets in fitful gusts; the Turkomans were burning the city. Still rose the wails of terror and agony and the yells of gloating rage. Cormac stepped over the body of a Jew that lay in a crimson pool. Zuleika noted with a shudder that the fingers had been cut away—even in death the Jew clung to his pitiful treasures. A wave of nausea surged over her and she pressed her face against her captor’s mailed shoulder, shutting out the sights of horror. A sudden fierce shout caused her to look up again.

Cormac was striding toward a huge black stallion of savage mien that stood with reins hanging in the street, and a tall warrior in heron plumed helmet and gold-chased mail was running toward him, holding a dripping scimitar. Zuleika realized that the warrior desired her, and even in that moment felt that he was made to dispute possession of a slave with the grim Frank, when so many women could be had for the taking. Cormac shifted her so his body shielded her, and drew his heavy sword. As the warrior leaped in the Frank struck as a lion strikes and the Turkoman’s head rolled in the bloody dust. Kicking aside the slumping body, Cormac reached his steed which reared and snorted with flaring nostrils at the scent of blood. But neither his steed’s restiveness nor his captive hampered the Frank who swung easily into the saddle and galloped toward the shattered gates.

The smoke, the blood and the clamor faded behind them and the upland desert closed in about them. Zuleika glanced up at the grim, inscrutable face of her new master and a strange whimsy crossed her mind. What girl has not dreamed of being borne away on the saddle bow of her prince of romance? So Zuleika had dreamed in other days. Long suffering had cleansed her of bitterness, but she wondered helplessly at the whim of chance. “On the saddle-bow she was borne away” but her garments were not the robes of a princess but the shift of a slave, not to the lilt of harps she rode, but the slavering howls of horror and slaughter, and her captor was not the prince of her childish dreams but a grim outlaw, stark and savage as the mountain land that bred him.

The castle of the Sieur Amory sat in the midst of a wild land. Built originally by Crusaders, it had fallen to the Seljuks, from whom it had again been captured by the craft and desperate courage of its present owner. It was one of the few waste-land holds that remained to the Franks, an outpost that rose boldly in hostile land. Leagues lay between Amory’s keep and the nearest Christian castle. South lay the desert. To the east, across the sands loomed the wild mountains wherein lurked savage foes.

Night had fallen and Amory sat in an inner chamber listening attentively to his guest. Amory was tall, rangy and handsome with keen grey eyes and golden locks. His garments had once been rich and costly but now they were worn and faded. The gems that had once adorned his sword hilt were gone. Poverty was reflected in his apparel as well as in the castle itself, which was barren beyond the wont of even the feudal castles of that rude day. Amory lived by plunder, as a wolf lives, and like a desert wolf, his life was lean and hard.

He sat on the rude bench, chin on fist and gazed at his guests. His was one of the few castles open to Cormac FitzGeoffrey. There was a price on the outlaw’s head and the slim holdings of the Franks in Outremer were barred to him, but here beyond the border none knew what went on in the isolated hold.

Cormac had quenched his thirst and satisfied his hunger with gigantic draughts of wine and huge bits of meat torn by his strong teeth from a roasted joint, and Zuleika had likewise eaten and drunk. Now the girl sat patiently, knowing that the warriors discussed her, but not understanding their Frankish speech.

“And so,” Cormac was saying, “when I heard the Turkomans had laid siege to the city, I rode hard to come up to it, knowing that it would not long withstand them, what with that fat fool of a Yurzed Beg commanding the walls. Well, it fell before I could arrive and when I came into it, the desert men had stripped it bare—the lucky ones had all the loot in sight and the others were scorching the toes of the citizens to make them give up their hidden wealth—but I did find this girl.”

“What of her, then?” asked Amory curiously. “She is pretty—dressed in costly apparel she might even be beautiful. But after all, she is only a half naked slave. No one will pay you much for her.”

Cormac grinned bleakly and Amory’s interest quickened. He had had much dealings with the Irish warrior and he knew when Cormac smiled, things were afoot.

“Did you ever hear of Zalda, the daughter of the Sheikh Abdullah bin Kheram, of the Roualli?”

Amory nodded and the girl, catching the Arabic words, looked up with sudden interest.

“She was about to be married, three years ago,” said Cormac, “to Khalru Shah, chief of Kizil-hissar, but a roving band of Kurds kidnapped her, and since then no word has been heard of her. Doubtless the Kurds sold her far to the East—or cut her throat. You never saw her? I did—these Bedouin women go unveiled. And this Arab girl, Zuleika, is enough like the princess Zalda to be her sister, by Crom!”

“I begin to see what you mean,” said Amory.

“Khelru Shah,” said Cormac, “will pay a mighty ransom for his bride. Zalda was of royal blood—marrying her meant alliance with the Roualli—the Sheikh is more powerful than many princes—when he summons his war-men, the hoofs of three thousand steeds shake the desert. Though he dwells in the felt tents of the Bedouin, his power is great, his wealth is great. No dowry was to go with the princess Zalda, but Khelru Shah was to pay for the privilege of wedding her—of such pride are these wild Rouallas.

“Keep the Arab girl here with you. I will ride to Kizil-hissar and lay my terms before the Turk. Keep her well concealed and let no Arab see her—she might be mistaken for Zalda, indeed, and if Abdullah bin Kheram gets wind of it, he might bring up against us such a force as to take the castle by storm.

“By continuous riding I can reach Kizil-hissar in three days; I will waste no more than a day in disputing with Khelru Shah. If I know the man, he will ride back with me, with several hundred men. We should reach this castle not later than four days after we depart from the hill-town. Keep the gates close barred while I am away, and ride not far afield. Khelru Shah is as subtle and treacherous as—”

“Yourself,” finished Amory with a grim smile.

Cormac grunted. “When we come, we will ride up to the walls. Then bring you the Arab slave upon the walls of the tower—somewhere you must contrive to find clothing more suited to a captive princess. And impress upon her that she must bear herself, at least while on the wall, with less humility. The princess Zalda was proud and haughty as an empress and bore herself as if all lesser beings were dust beneath her white feet. And now I ride.”

“In the midst of the night?” asked Amory. “Will you not sleep in my castle and ride forth at dawn?”

“My horse is rested,” answered Cormac, “I never weary. Besides I am a hawk that flies best by night.”

He rose, pulling his mail coif in place and donning his helmet. He took up his shield which bore the symbol of a grinning skull. Amory looked at him curiously, and though he knew the man of old, he could not but wonder at the wild spirit and self sufficiency that enabled him to ride by night across a savage and hostile land, into the very strong hold of his natural foes. Amory knew that Cormac FitzGeoffrey was outlawed by the Franks for slaying a certain nobleman, that he was fiercely hated by the Saracens as a hold, and that he had half a dozen private feuds on his hands, both with Christian and Moslem. He had few friends, no followers, no position of power. He was an outcast who must depend on his own wit and prowess to survive. But these things sat lightly on the soul of Cormac FitzGeoffrey; to him they were but natural circumstances. His whole life had been one of incredible savagery and violence.

Amory knew that conditions in Cormac’s native land were wild and bloody, for the name of Ireland was a term of violence all over Western Europe. But just how war-shaken and turbulent those conditions were, Amory could not know. Son of a ruthless Norman adventurer on one hand, and a fierce Irish clan on the other, Cormac FitzGeoffrey had inherited the passions, hates and ancient feuds of both races. He had followed Richard of England to Palestine and won a red name for himself in the blind melee of that vain Crusade. Returning again to Outremer to pay a debt of gratitude, he had been caught in the blind whirlwind of plot and intrigue and had plunged into the dangerous game with a fierce zest. He rode alone, mostly, and time and again his many enemies thought him trapped, but each time he had won free, by craft and guile, or by the sheer power of his sword arm. For he was like a desert lion, this giant Norman-Gael who plotted like a Turk, rode like a Centaur, fought like a blood-mad tiger and preyed on the strongest and fiercest of the outland lords.

Full armed he rode into the night on his great black stallion, and Amory turned his casual attention to the slave girl. Her hands were soiled and roughened with menial toil, but they were slender and shapely. Somewhere in her veins, decided the young Frenchman, ran aristocratic blood, that showed in the delicate rose leaf texture of her skin, in the silkiness of her wavy black hair, in the deep softness of her dark eyes. All the warm heritage of the Southern desert was evident in her every motion.

“You were not born a slave?”

“What does it matter, master?” she asked. “Enough that I am a slave now. Better be born to the whips and chains than broken to them. Once I was free; now I am thrall. Is it not enough?”

“A slave,” muttered Amory. “What are a slave’s thoughts? Strange—it never before occurred to me to wonder what passes in the mind of a slave—or a beast, either, for that matter.”

“Better a man’s steed, than a man’s slave, master,” said the girl.

“Aye,” he answered, “for there is nobility in a good horse.”

She bowed her head and folded her slender hands, unspeaking.

Dusk shadowed the hills when Cormac FitzGeoffrey rode up to the great gate of Kizil-hissar, the Red Castle, which gave its name to the town it guarded and dominated. The guardsmen, lean, bearded Turks with the eyes of hawks, cursed in amazement.

“By Allah, and by Allah! The wolf has come to put his head in the trap! Run, Yaser, and tell our lord, Suleyman Bey, that the infidel dog, Cormac, stands before the gates.”

“Ho there, you upon the walls!” shouted the Frank. “Tell your chief that Cormac FitzGeoffrey would have speech with him. And make haste, for I am not one to waste time in dallying.”

“Hold him in parley but a moment,” muttered a Moslem, crouching behind a bastion, and winding his cross-bow—a ponderous affair captured from the Franks, “I’ll send him to dress his shield in Hell.”

“Hold!” this from a bearded, lean old hawk whose eyes were fierce and wary. “When this chief rides boldly into the hands of his enemies, be sure he has secret powers. Wait until Suleyman comes.” To Cormac he called courteously, “Be patient, mighty lord; the prince Suleyman Bey has been sent for and will soon be upon the walls.”

“Then let him come in haste,” growled Cormac, who was in no more awe of a prince than he was of a peasant. “I will not await him long.”

Suleyman Bey came upon the great walls and looked down curiously and suspiciously upon his enemy.

“What want ye, Cormac FitzGeoffrey?” he asked. “Are you mad, to ride alone to the gates of Kizil-hissar? Have you forgotten there is feud between us? That I have sworn to sever your neck with my sword?”

“Aye, so you have sworn,” grinned Cormac, “and so has sworn Abdullah bin Kheram, and Ali Bahadur, and Abdallah Mirza the Kurd. And so, in past years and in another land, swore Sir John Courcey, and the clan of the O’Donnells and Sir William Le Botelier, yet I still wear my head firmly on my shoulders.

“Harken till I tell you what I have to say. Then if you still wish my head, come out of your stone walls and see if ye be man enough to take it. This concerns the princess Zalda, daughter of Sheikh Abdullah bin Kheram—on whose name, damnation!”

Suleyman Bey stiffened with sudden interest; he was a tall, slender man, young, and handsome in a hawk-like way. His short black beard set off his aristocratic features and his eyes were fine and expressive, with shadows of cruelty lurking in their depths. His turban was scaled with silver coins and adorned with heron plumes, and his light mail was crusted with golden scales. The hilt of his slender, silver chased scimitar was set with gleaming gems. Young but powerful was Suleyman Bey, in the hill-town upon which he had swooped with his hawks a few years before and made himself ruler. Six hundred men of war he could bring to battle, and he lusted for more power. For that reason he had wished to ally himself with the powerful Roualla tribe of Abdullah bin Kheram.

“What of the princess Zalda?” he asked.

“She is my captive,” answered Cormac.

Suleyman Bey started violently, his hand gripped his hilt, then he laughed mockingly.

“You lie; the princess Zalda is dead.”

“So I thought,” answered Cormac frankly. “But in the raid on the city, I found her captive to a merchant who knew not her real identity, she having concealed it, fearing lest worse evil come to her.”

Suleyman Bey stood in thought a moment, then raised his hand.

“Open the gates for him. Enter, Cormac FitzGeoffrey, no harm shall come to you. Lay down your sword and ride in.”

“I wore my sword in the tent of Richard the Lion-hearted,” roared the Norman. “When I unbuckle it in the walls of my foes, it will be when I am dead. Unbar those gates, fools, my steed is weary.”

Within an inner chamber of silk and crimson hangings, crystal and gold and teak-wood, Suleyman Bey sat listening to his guest. The young chief ’s face was inscrutable but his dark eyes were absorbed. Behind him stood, like a dark image, Belek the Egyptian, Suleyman’s right-hand man, a big, dark powerful man with a satanic face and evil eyes. Whence he came, who he was, why he followed the young Turk none knew but Suleyman, but all feared and hated him, for the craft and cruelty of a black serpent was in the abysmal brain of the Egyptian.

Cormac FitzGeoffrey had laid aside his helmet and thrown back his mail coif, disclosing his thick, corded throat, and his black, square cut mane. His volcanic blue eyes blazed even more fiercely as he talked.

“Once the princess Zalda is in your hands you can bring the Sheikh to terms. Instead of paying him a great price for her, you can force him to pay you a dowry. He had rather see her your wife, even at the cost of much gold, than your slave. Once married to her, then, he will join forces with you. You will have all that you planned for three years ago, in addition to a rich dowry from the Sheikh.”

“Why did you not ride to him instead of to me?” abruptly asked Suleyman.

“Because you have such things as we desire, my friend and I. Abdullah is more powerful than you, but his treasure is less. Most of his belongings consist of cattle—horses—arms—tents—fields—the belongings of a Nomad chief. Here in this castle you have chests of golden coins looted from caravans and taken as ransom for captive knights. You have gems—silver—silks—rare spices—jewelry. You have what we desire.”

“And what proof have I that you are not lying?”

“Ride with me tomorrow,” grunted Cormac, “to the castle of my friend.”

Suleyman laughed like a wolf snarling.

“You would lead us into a trap,” said the Egyptian.

“Bring three hundred men with you, bring as many as you like, the whole band of thieves,” said Cormac. “Where do you think I would get enough warriors to trap your whole host?”

“Where is she being held?” asked the Seljuk.

“In the castle of the Sieur Amory, three, four days ride to the west,” said Cormac. “You could never take it by assault.”

“I am not sure,” muttered Suleyman. “The lord Amory has only some forty men-at-arms.”

“But the castle is impregnable.”

“So I have heard.”

The Egyptian’s eyes narrowed.

“We might seize you and hold you for ransom,” he suggested, “and force the Sieur Amory to return the girl.”

Cormac laughed savagely and mockingly.

“Amory would laugh at you and tell you to cut my throat and be damned, or he would cut the throat of the girl as it struck him. Besides, though I am in your castle, surrounded by your warriors, I am not entirely helpless. Seek to take me and I will flood these walls with blood before I die.”

It was no idle boast as the Moslems well knew.

“Enough,” Suleyman made an impatient gesture. “You are promised safety—what’s that?”

A commotion had arisen without; a scuffling, shouts, threats and maledictions in the Arab tongue. The outer door was thrust open and a bearded Turk who had been guarding the door entered, dragging a struggling victim whose beard bristled with wrath. He clung to a pack from which spilled various trinkets and ornaments.

“I found this dog sneaking about in an adjoining chamber, master,” rumbled the guardsmen. “Methinks he was eavesdropping. Shall I not strike off his head?”

“I am Ali bin Nasru, an honest merchant!” shouted the Arab angrily and fearfully. “I am well known in Kizil-hissar! I sell wares to shahs and sheikhs and I was not eavesdropping. Am I a dog to spy upon my patron? I was seeking the great chief Suleyman Bey to spread my goods before him!”

“Best cut out his tongue,” growled Belek. “He may have heard too much.”

“I heard nothing!” clamored Ali. “I have but just come into the castle!”

“Beat him forth,” snapped Suleyman Bey in irritation. “Shall I be pestered by a yapping cur? Lash him out and if he comes again with his trash, strip him and hang him up by his feet in the market-place for the children to pelt with stones. Cormac, we ride at dawn, and if you have tricked me, make your peace with Allah!”

“And if you seek to trick me,” snarled Cormac, “make your peace with the Devil for you will swiftly meet him.”

It was past midnight when a form climbed warily down a rope let down from the outer wall of the town. Hurriedly making his way down the slopes, the man came soon upon a thicket where was securely hidden a swift camel and a bulky pack—for the man was not one to trust all his belongings in a town ruled by Turks. Recklessly casting aside the pack, the man mounted the camel and fled southward.

Amory rested his chin on his fist and gazed broodingly at the Arab girl, Zuleika. In the past days he had found his eyes straying often to his slender captive. He wondered at her silence and submission, for he knew that at some time in her life, she had known a higher position than that of a slave. Her manners were not those of a born serf; she was neither impudent nor servile. He guessed faintly at the fierce and cruel school in which she had been broken—no, not broken, for there was a strange deep strength in her that had not been touched, or if touched, only made more pliable.

She was beautiful—not with the passionate, fierce beauty of the Turkish women who had lent him their wild love, but with a deep, tranquil beauty, of one who’s soul has been forged in fierce fires.

“Tell me how you came to be a slave.” The voice was one of command and Zuleika folded her hands in acquiescence.

“I was born among the black felt tents of the south, master, and my childhood was spent upon the desert. There all things are free—in my early girlhood I was proud, for men told me I was beautiful, and many suitors came to woo me. But there came others, too—men who wooed with naked steel and me they carried off.

“They sold me to a Turk, who soon wearied of me and sold me again to a Persian slave-dealer. Thus I came into the house of the merchant of the city, and there I toiled, a slave among the lowest slaves. My master once offered me my freedom if I would return his love but I could not. My body was his; my love he could not shackle. So he made of me his drudge.”

“You have learned deep humility,” commented Amory.

“By scourge and shackle and torture and toil I have learned, master,” she said.

“Do you know what we mean to do with you?” he asked bluntly. She shook her head.

“Cormac thinks you resemble the princess Zalda,” said Amory, “and it is our intention to cheat Suleyman Bey with you. We will show you to him on the wall, and I think he will pay a high price for you. When we have delivered you to him, you will have your chance. Play your cards well and perchance you may bewitch him, so when he learns of the trickery, he will not put you aside.”

Again Amory’s eyes swept over her slim form. A pulse began to thrum in his temple. For the time being, she was his; why should he not take her, before he gave her into the arms of Suleyman Bey? He had learned that what a man wants he must take. With a single long stride he reached her and swept her into his arms. She made no resistance, but she averted her face, drawing her head back from his fierce lips. Her dark eyes looked into his with a deep hurt and suddenly he felt ashamed. He released her and turned away.

“There are some garments I bought from a wandering band of gypsies,” he said abruptly. “Put them on; I hear a trumpet.”

Across the desert a distant trumpet was faintly sounding. Amory had his men in full armor lining the walls, weapons in hand, when the horsemen rode up to the castle gate, which was flanked by a tower.

Amory hailed them. He saw Suleyman Bey in heron plumed helmet and gold scaled mail, sitting his black mare. Close behind him sat Belek the Egyptian on a bay horse, and beside the chief, Cormac FitzGeoffrey on his great stallion. And Amory grinned. Was it not strange to see the man riding in the company of those who had sworn to cut his throat? Some three hundred riders were ranked behind the chief.

“Ha, Amory,” said Cormac, “fetch forth the princess—let her be shown upon the wall of the tower that Suleyman Bey be convinced; he thinks us liars, by the hoofs of the Devil!”

Amory hesitated, as a sudden revulsion shook him, then with a shrug of his shoulders he made a gesture to his men-at-arms. Zuleika was escorted out upon the wall above the gate and Amory gasped. Rich clothes had wrought a transformation in the slave girl; indeed she wore them as if she had never worn the flimsy rags of a serf. She did not carry herself with the haughty pride of a princess, thought Amory, but there was a certain quiet dignity about her, a certain proud humility that many of royal blood might well copy.

Suleyman Bey gasped also; he gazed at her in bewilderment and reined closer.

“By Allah!” he said in amazement. “Zalda! Is it she? No—yes—by Asrael, I cannot say! She does not carry her chin as she did, if it be she, and yet—yet—by the gods, it must be she!”

“Of a surety it is the princess Zalda!” rumbled Cormac. “By Satan, do you think there is no faith in Franks? Well, chief, what say you? Is she worth ten thousand pieces of gold to you?”

“Wait,” answered the Turk, “I must have time to consider. This girl is alike the princess Zalda as can be—yet her whole bearing is different—I must be convinced. Let her speak to me.”

Amory nodded to Zuleika who gave him a pitiful look, then raising her voice, said: “My lord, I am Zalda, daughter of Abdullah bin Kheram.”

Again the Turk shook his hawk-like head.

“The voice is soft and musical like Zalda’s, but the tone is different—the princess was used to command and her tone was imperious.”

“She has been a captive,” grunted Cormac. “Three years of captivity can change even a princess.”

“True—well, I will ride to the spring of Mechmet which lies something more than a mile away, and there camp. Tomorrow I will come to you again and we will talk on the matter. Ten thousand pieces of gold—a high price to pay, even for the princess Zalda.”

“Good enough,” grunted Cormac, “I’ll remain at the castle—and mark you, Suleyman—no tricks. At the first hint of a night onset we cut Zalda’s throat and throw her head to you. Mark!”

Suleyman nodded absent mindedly and rode away at the head of his riders, in deep converse with the dark faced Belek. Cormac rode in through the gate which was instantly barred and bolted behind him, and Zuleika turned to go into her chamber. Her head was bent, her hands folded; again she had assumed the manner of the slave. Yet she paused a moment before Amory and in her dark eyes was a deep hurt as she said: “You will sell me to Suleyman, my lord?”

Amory flushed darkly—not in years had the blood thus suffused his face. He sought to reply and groped for words. Unconsciously his mailed hand sought her slim shoulder, half caressingly. Then he shook himself and spoke harshly because of the strange conflicting emotions within him: “Go to your chamber, wench; what affair of yours is it what I do?”

And as she went, head sunk on her breast, he stood looking after her, clenching his mailed fists until the fingers cracked, and cursing himself bewilderedly.

Cormac FitzGeoffrey and Amory sat in an inner chamber, though the hour was late. Cormac was in full armor, except for his helmet, as was Amory. The mail coifs of both men were drawn back upon their shoulders, disclosing Amory’s yellow locks and Cormac’s raven mane. Amory was silent, moody; he drank little, talked less. Cormac, on the other hand, was in a mood of deep satisfaction. He drank deep and his gratification led him into a reminiscent mood.

“Wars and massed battles I have seen in plenty,” said he, lifting his great goblet. “Aye—I fought in the battle of Dublin when I was but eight years old, by the hoofs of the Devil! Miles de Cogan and his brother Richard held the city for Strongbow—men of iron in an iron age. Hasculf Mac Turkill, King of Dublin, who had been driven into the Orkneys, came sailing up the strand with sixty-five ships—galleys of the heathen Norsemen, whose chief was the berserk Jon the Mad—and mad he was, by the hoofs of Satan! So Hasculf came back to win his city again, with his Danes and Dano-Irish, and his allies from Norway and the Isles.

“Word of the war came into the west, where I was a boy running half naked on the moors, in the land of the O’Briens. We had a weapon-man whose name was Wulfgar and he was a Norseman. ‘I will strike one more blow for the sea-people,’ he said, and he went across the bogs and the fens as a wolf goes, and I went with him with my boy’s bow, for the urge of wandering and blood-letting was already upon me. So we came upon Dublin strand just as the battle was joined. By Satan, the Norsemen drove the Normans back into the city and were shattering the gates when Richard de Cogan made a sortie from the postern gate and fell upon them from the rear. Whereupon Sir Miles sallied from the main gates with his knights and the ravens fed deep! By Satan, there the axes drank and the swords failed not of glutting!

“So Wulfgar and I came into the battle and the first wounded man I saw was an English man-at-arms who had once crushed my ear lobe to a pulp so that the blood flowed over his mailed fingers, to see if he could make me cry out—I did not cry out but spat in his face, so he struck me senseless. Now this man knew me and called me by name, gasping for water. ‘Water is it?’ said I. ‘It’s in the icy rivers of hell you’ll quench your thirst!’ And I jerked back his head to cut his throat, but before I could lay dirk to gullet, he died. His legs were crushed by a great stone and a spear had broken in his ribs.

“Wulfgar was gone from me now and I advanced into the thick of the battle, loosing my arrows with all the might of my childish muscles, blindly and at random, so I do not know if I did scathe or not, or to whom, for the noise and shouting confused me and the smell of blood was in my nostrils, and the blindness and fury of my first massed battle upon me.

“So I came to the place where Jon the Mad was leagued with a few of his Vikings by the Norman knights—by Saint John, I never saw a man strike such blows as this berserk struck! He fought half naked and without mail or shield, and neither buckler nor armor could stand before his axe. And I saw Wulfgar—on a heap of dead he lay, still gripping a hilt from which the blade had snapped in a Norman knight’s heart. He was passing swiftly, his life ebbing from him in thick crimson surges but he spoke to me faintly and said, ‘Bend your bow, Cormac, against the big man in chain mail armor.’ And so he died and I knew he meant Miles de Cogan.

“But at that moment Jon, bleeding from a hundred wounds, struck a blow that hewed off a knight’s leg at the hip, though cased in heavy mail, and the axe haft splintered in the Viking’s hand, and Miles de Cogan gave him his death stroke. Now all the Norsemen were dead or fled, and the men-at-arms dragged King Hasculf Mac Turkill before Miles de Cogan, who had his head severed on the spot. Now that sight maddened me, for though I loved not the Dane, I hated the Normans more, and running forward across the torn corpses, I bent my bow against Miles de Cogan. It was my last arrow and it splintered on his breast plate. A man-at-arms caught me up and held me high for Miles to view, while I cursed him in Gaelic and broke my milk teeth on his mail-clad wrist.”

“ ‘By Saint George,’ said Miles, ‘it’s Geoffrey the Bastard’s Irish wolf-cub.’

“ ‘Crush him,’ said Richard de Cogan. ‘He’s half Gael—he’ll make a wolf for the O’Briens.’

“ ‘He’s half Geoffrey,’ said Miles. ‘He’ll make a good soldier for the king.’

“Well, both were right, but Miles came to curse the day he spared me. When I met him again in battle, years later, I gave him a wound that marked him for life.

“Barren fighting, in a barren land. By Satan, it seems though that now we are to be rewarded for our zeal. Did you station all the men-at-arms on the walls? It’s a dark, star-less night and we must beware of Suleyman Bey. Ha, we’ve cozened him! We are as good as richer by ten thousand gold pieces! Then you can rebuild this castle—hire more men-at-arms—buy armor and weapons. As for me, I’ll gather together a band of cut-throat ruffians and fare east in quest of some fat city to loot.”

“Cormac,” Amory’s eyes were dull and troubled, “what think you that Suleyman Bey will do with the girl Zuleika when he finds we’ve tricked him? Will he not slay her in his anger?”

“Not he,” Cormac drank deep. “He’ll use her to trick old Abdullah bin Kheram as we’ve tricked him. If the girl plays her cards right, she may be a queen yet.”

“Cormac,” said Amory abruptly, “I cannot do it.”

The Norman glared at him in bewilderment.

“What are you talking about?”

Amory spread his hands helplessly. “I am sorry. I realized it while she was on the wall—I cannot let this girl go—I love her—”

“What!” exclaimed Cormac, completely dumbfounded. “You mean you will keep her—not give her up to Suleyman Bey—why—!”

“I love her,” said Amory doggedly. “That is the only excuse I can give.”

Blue sparks of Hell’s fire began to flicker in Cormac’s eyes. His mailed fingers closed on the goblet and crunched it into ruin.

“You’d trick me, eh?” he roared. “You’d cheat me! It’s wolf bite wolf, is it, with your damned lust? You French dog, I’ll send you to pare the Devil’s nails!”

Amory reached swiftly for his sword as Cormac lunged from his seat, but the giant Irishman plunged full at his throat, splintering the heavy table to match-wood. Before the young Frenchman could clear his blade, the impact of Cormac’s hurtling mail-clad body knocked him staggering and he was fighting desperately to keep the Norman’s iron fingers from his throat. One of Cormac’s hands had locked like a vise in a fold of Amory’s mail at his neck, barely missing the throat and the other hand snapped for a death-hold. Amory’s face was pale for he had seen Cormac tear out a giant Turk’s throat with his naked fingers and he knew that once those iron hands closed on his gullet, no power on earth could loosen them before they tore out the life that pulsed beneath.

About the room they fought and wrestled, those two great, mailed fighting men, in a strange, silent battle. Cormac made no attempt to draw steel and Amory had no time to do so. With all his skill, swiftness and power, he was fighting a losing fight to keep clear of those terrible, clutching hands. Amory struck with all his power, driving his clenched, iron guarded fist full into Cormac’s face and blood spattered, but the terrific blow did not check the Norman in the slightest—Amory did not even think Cormac blinked. They crashed headlong into the ruins of the table and as they fell, close-clinched, Cormac roared short and thunderous, as his fingers locked at last in the hold he had sought. Instantly Amory’s head began to swim and the candle-light went bloody to his distended gaze. Cormac’s fingers were sunk in the loose folds of his coif which, thrown back from his head, lay loosely about his neck, and only this saved him from instant death, but even so he felt his senses going. He tore and ripped futilely at Cormac’s wrists; his head was bent back at an excruciating angle—his neck was about to snap—there came a swift rush of feet in the corridor without—a wild eyed man-at-arms burst into the chamber.

“My lords—masters—the paynim—they are within the wall and the castle burns!”

The sounds of the castle faded as the guardsmen took up their posts and the rest composed themselves for sleep. In the great hall the beggar stirred; from his rags eyes strangely unsuited to a beggar glinted; eyes like a basilisk’s. With a swift motion he rose, throwing off his filthy, tattered garments, revealing the Mephistophelean countenance and pantherish form of Belek the Egyptian. Clad only in a striped loin cloth and with a long dagger in his hand, he stole through the great hall and up the winding stair like a ghost.

Over all the castle silence reigned; before Zuleika’s door the sleepy man-at-arms yawned and leaned on his pike drowsily. What use for a guard before an inner chamber? What pagan could win through the walls without rousing the whole force of the defenders? The guard did not hear the naked feet that stole noiselessly along the flags. He did not see the dusky figure that glided behind him. But he felt suddenly an iron arm encircle his throat strangling the startled yell that sought to rise to his lips, he felt the momentary agony of a hard driven blade that pierced his heart, and then he felt no more.

Belek eased the limp body to the floor and swiftly detached the keys from the belt. He selected one and opened the door, working with speed but silence. He slipped inside, closing the door.

Zuleika wakened with the realization that some one was in her chamber, but in the utter darkness she could see no one. But Belek could see like a cat in the dark. Zuleika felt a sudden hand clapped over her mouth and as she instinctively lifted her hands to ward off that attack, her slim wrists were pinioned together.

“Keep still, princess,” hissed a voice in the gloom. “If you scream, you die.”

The hand was withdrawn from her lips and Zuleika felt her hands being bound; next a gag was placed in her mouth. Belek the Egyptian had his own ideas about handling women. He had been sent to rescue Zuleika, yes; but he knew that women quite often prefer not to be rescued from their captors and he was taking no chances that the girl might prefer to remain with her present masters than to ride away with Suleyman Bey. Belek did not intend that a woman’s scream should bring him to his doom.

He lifted his slender captive and carrying her carefully over one shoulder, stole down the corridor cautiously, dagger ready. He descended the stair and stole through the great kitchen. He heard the cook snoring in the pantry. Ordinarily it would have been impossible for a man to steal through the castle of the Sieur Amory without detection, but tonight all the men were on the walls, or else sleeping soundly awaiting their call to guard-duty.

Belek warily unbolted a small door and slipped outside, keeping close to the walls. It was dark as pitch, low hanging clouds obscuring the stars, and there was no moon. Belek hesitated, for the moment uncertain; then he crossed the courtyard swiftly and entered the stables. He knew that Cormac’s great black stallion was quartered here, and he trembled lest he rouse the full passion of the savage brute, which might make enough noise to wake the whole castle. But Belek’s stealthy entrance caused no commotion; the great beast had his stall in another part of the stables. The Egyptian laid the girl in an empty stall, first tying her ankles, then stole swiftly back to the castle. Entering the kitchen he crossed to the small room where firewood was kept piled, and busied himself a few moments. Then he shut the door and hurriedly left the castle once more. A faint, grim smile played over his thin lips.

And now he was ready for the most dangerous part of his daring night’s work. Crouching like a panther he stole across the courtyard to the postern gate. A single man-at-arms stood there, leaning on his spear and half asleep; it was the hour of darkness before dawn when vitality is at a low ebb. Belek crouched and leaped, silent and deadly as a panther. His mighty hand locked about his victim’s throat and the man died without a cry.

Belek worked cautiously at the gate, felt it move beneath his hands and swing inward. He crouched silently, almost holding his breath, straining his eyes into the night. He could make out the dim somber reaches of the desert knifed with ravines and gulches; were men moving out there? Not even the keen eyed Egyptian could tell for the clouds hung low and deep darkness rested over all. He thought of returning for the girl and slipping out with her, then abandoned the plan. The men on the wall above him were not asleep. Their low voiced snatches of conversation reached him from time to time. He had stolen to the postern gate and killed his man almost beneath their feet, but it was behind their back. Their gaze was turned outward; they would see anything that moved just without the wall and if he stole forth, arrows would fall like rain about him. Alone he would have taken the risk; but he dared not take the chance with the girl.

Out among the ravines a jackal yapped three times and ceased. Belek grinned fiercely; Suleyman Bey had not failed to carry out his part of the plan. Behind him he heard a cracking and snapping that grew and grew; a lurid light became apparent through the aperture of the castle and the men on the wall began to talk loudly and hastily as a sudden wild yell went up from inside the keep. As if in answer a clamor of ferocious shouts sounded from the desert outside and suddenly the darkness was alive with charging shadows.

Belek shouted once himself, in fierce triumph, and ran swiftly to the stable where he had left the girl.