Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

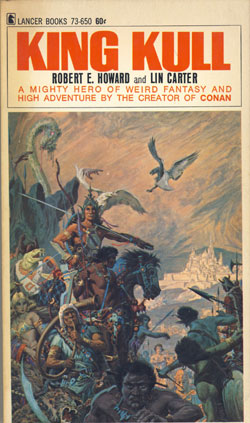

Published in King Kull, 1967.

Men still name it The Day of the King’s Fear. For Kull, king of Valusia, was only a man after all. There was never a bolder man, but all things have their limits, even courage. Of course Kull had known apprehension and cold whispers of dread, sudden starts of horror, and even the shadow of unknown terror. But these had been but starts and leapings in the shadow of the mind, caused mainly by surprise or some loathsome mystery or unnatural thing—more repugnance than real fear. So real fear in him was so rare a thing that men mark the day.

Yet there was a time that Kull knew Fear, stark, terrible, and unreasoning, and his marrow weakened and his blood ran cold. So men speak of the time of Kull’s Fear, and they do not speak in scorn, nor does Kull feel any shame. No, for as it came about, the thing rebounded to his undying glory.

Thus it came to be. Kull sat at ease on the Throne of Society, listening idly to the conversation of Tu, chief councilor; Ka-nu, ambassador from Pictdom; Brule, Ka-nu’s right-hand man; and Kuthulos the slave, who was yet the greatest scholar in the Seven Empires.

“All is illusion,” Kuthulos was saying. “All outward manifestations of the underlying Reality, which is beyond human comprehension, since there are no relative things by which the finite mind may measure the infinite. The one may underlie all, or each natural illusion may possess a basic entity. All these things were known to Raama, the greatest mind of all the ages, who eons ago freed humanity from the grasp of unknown demons and raised the race to its heights.”

“He was a mighty necromancer,” said Ka-nu.

“He was no wizard,” said Kuthulos. “No chanting, mumbling conjurer, divining from snake’s livers. There was naught of mummery about Raama. He had grasped the First Principles; he knew the Elements and he understood that natural forces, acted upon by natural causes, produced natural results. He accomplished his apparent miracles by the exercise of his powers in natural ways, which were as simple in their manner to him as lighting a fire is to us, and as much beyond our ken as our fire would have been to our ape-ancestors.”

“Then why did he not give all his secrets to the race?” asked Tu.

“He knew it is not good for man to know too much. Some villain would subjugate the whole race, nay, the whole universe, if he knew as much as Raama knew. Man must learn by himself and expand in soul as he learns.”

“Yet, you say all is illusion,” persisted Ka-nu, shrewd in statecraft, but ignorant in philosophy and science, and respecting Kuthulos or his knowledge. “How is that? Do we not hear and see and feel?”

“What is sight and sound?” countered the slave. “Is not sound the absence of silence, and silence absence of sound? The absence of a thing is not material substance. It is—nothing. And how can nothing exist?”

“Then why are things?” asked Ka-nu like a puzzled child.

“They are appearances of reality. Like silence; somewhere exists the essence of silence, the soul of silence. Nothing that is something; an absence so absolute that it takes material form. How many of you ever heard complete silence? None of us! Always there are some noises—the whisper of the wind, the flutter of an insect, even the growing of the grass, or on the desert, the murmur of the sands. But at the centre of silence, there is no sound.”

“Raama,” said Ka-nu, “long ago shut a spectre of silence into a great castle and sealed it there for all time.”

“Aye,” said Brule. “I have seen the castle: a great black thing on a lone hill, in a wild region of Valusia. Since time immemorial it has been known as the Skull of Silence.”

“Ha!” Kull was interested now. “My friends, I would like to look upon this thing!”

“Lord king,” said Kuthulos, “it is not good to tamper with what Raama made fast. For he was wiser than any man. I have heard the legend that by his arts he imprisoned a demon; not by his arts, say I, but by his knowledge of the natural forces, and not a demon but some element which threatened the existence of the race.

“The might of that element is evinced by the fact that not even Raama was able to destroy it; he only imprisoned it.”

“Enough,” Kull gestured impatiently. “Raama has been dead so many thousand years that it wearies me to think on it. I ride to find the Skull of Silence; who rides with me?”

All of those who listened to him, and a hundred of the Red Slayers, Valusia’s mightiest war force, rode with Kull when he swept out of the royal city in the early dawn. They rode up among the mountains of Zalgara, and after many days’ search they came upon a lone hill rising sombrely from the surrounding plateaus, and on its summit a great stark castle, black as doom.

“This is the place,” said Brule. “No people live within a hundred miles of this castle, nor have they in the memory of man. It is shunned like a region accursed.”

Kull reined his great stallion to a halt and gazed.

No one spoke, and Kull was aware of the strange, almost intolerable stillness. When he spoke again, everyone started. To the king, it seemed that waves of deadening quiet emanated from that brooding castle on the hill. No birds sang in the surrounding land, and no wind moved the branches of the stunted trees. As Kull’s horsemen rode up the slope, their footfalls on the rocks seemed to tinkle drearily and far away, dying without echo.

They halted before the castle that crouched there like a dark monster, and Kuthulos again essayed to argue with the king.

“Kull, consider! If you burst that seal, you may loose upon the world a monster whose might and frenzy no man can stay!”

Kull, impatient of restraint, waved him aside. He was in the grip of a wayward perverseness, a common fault of kings, and though usually reasonable, he had now made up his mind and was not to be swerved from his course.

“There are ancient writings on the seal, Kuthulos,” he said. “Read them to me.”

Kuthulos unwillingly dismounted, and the rest followed suit, all save the common soldiers who sat their horses like bronze images in the pale sunlight. The castle leered at them like a sightless skull, for there were no windows whatever and only one great door, that of iron and bolted and sealed. Apparently the building was all in one chamber.

Kull gave a few orders as to the disposition of the troops and was irritated when he found he was forced to raise his voice unseemingly in order for the commanders to understand him. Their answers came dimly and indistinctly.

He approached the door, followed by his four comrades. There on a frame beside the door hung a curious-appearing gong, apparently of jade, a sort of green in color. But Kull could not be sure of the color, for before his amazed stare it changed and shifted, and sometimes his gaze seemed to be drawn into depths and sometimes to glance at extreme shallowness. Beside the gong hung a mallet of the same strange material. He struck it lightly and then gasped, nearly stunned by the crash of sound which followed—it was like all earthly noise concentrated.

“Read the writings, Kuthulos,” he commanded again, and the slave bent forward in considerable awe, for no doubt these words had been carved by the great Raama himself.

“That which was, may be again,” he intoned. “Then beware, all sons of men!”

He straightened, a look of fright on his face. “A warning! A warning straight from Raama! Mark ye, Kull, mark ye!”

Kull snorted, and drawing his sword, rent the seal from its hold and cut through the great metal bolt. He struck again and again, dimly aware of the comparative silence with which the blows fell. The bars fell, the door swung open.

Kuthulos screamed. Kull reeled, stared—the chamber was empty? No! He saw nothing, there was nothing to see, yet he felt the air throb about him as something came billowing from that foul chamber in great unseen waves. Kuthulos leaned to his shoulder and shrieked, and his words came faintly as from over cosmic distance.

“The Silence! This is the soul of all Silence!”

Sound ceased. Horses plunged and their riders fell face first into the dust and lay clutching at their heads with their hands, screaming without sound. Kull alone stood erect, his futile sword thrust in front of him. Silence! Utter and absolute! Throbbing, billowing waves of still horror. Men opened their mouths and shrieked, but there was no sound!

The Silence entered Kull’s soul; it clawed at his heart; it sent tentacles of steel into his brain. He clutched at his forehead in torment; his skull was bursting, shattering. In the wave of horror which engulfed him, Kull saw red and colossal visions: the Silence spreading out over the Earth, over the Universe! Men died in gibbering stillness; the roar of rivers, the crash of seas, the noise of winds faltered and ceased to be. All Sound was drowned by the Silence. Silence, soul-destroying, brain-shattering; blotting out all life on Earth and reaching monstrously up into the skies, crushing the very singing of the stars!

And then Kull knew fear, horror, terror—overwhelming, grisly, soul-killing. Faced by the ghastliness of his vision, he swayed and staggered drunkenly, gone wild with fear. Oh gods, for a sound, the very slightest, faintest noise! Kull opened his mouth like the groveling maniacs behind him, and his heart nearly burst from his breast in his effort to shriek.

The throbbing stillness mocked him. He smote against the metal sill with his sword. And still the billowing waves flowed from the chamber, clawing at him, tearing at him, taunting him like a being sensate with terrible Life.

Ka-nu and Kuthulos lay motionless. Tu writhed on his belly, his head in his hands, and squalled soundlessly like a dying jackal. Brule wallowed in the dust like a wounded wolf, clawing blindly at his scabbard.

Kull could almost see the form of the Silence now, the frightful Silence that was coming out of its Skull at last, to burst the skulls of men. It twisted, it writhed in the unholy wisps and shadows, it laughed at him! It lived! Kull staggered and toppled, and as he did, his outflung arm struck the gong. Kull heard no sound, but he felt a distinct throb and jerk of the waves about him, a slight withdrawal, involuntary, just as a man’s hand jerks back from the flame.

Ah, old Raama left a safeguard for the race, even in death! Kull’s dizzy brain suddenly read the riddle. The sea! The gong was like the sea, changing green shades, never still, now deep and now shallow, never silent.

The sea! Vibrating, pulsing, booming day and night; the greatest enemy of the Silence. Reeling, dizzy, nauseated, he caught up the jade mallet. His knees gave way, but he clung with one hand to the frame, clutching the mallet with the other in a desperate death grip. The Silence surged wrathfully about him.

Mortal, who are you to oppose me, who am older than the gods? Before Life was, I was, and shall be when Life dies. Before the invader Sound was born, the Universe was silent and shall be again. For I shall spread out through all the cosmos and kill Sound—kill Sound—kill Sound—kill Sound!

The roar of Silence reverberated through the caverns of Kull’s crumbling brain in abysmal chanting monotones as he struck on the gong—again—and again—and again!

And at each blow the Silence gave back—inch by inch—inch by inch. Back, back, back. Kull renewed the force of his mallet blows. Now he could faintly hear the faraway tinkle of the gong, over unthinkable voids of stillness, as if someone on the other side of the Universe were striking a silver coin with a horse-shoe nail. At each tiny vibration of noise, the wavering Silence started and shuddered. The tentacles shortened, the waves contracted. The Silence shrank. Back and back and back—and back. Now the wisps hovered in the doorway, and behind Kull, men whimpered and wallowed to their knees, chins sagging and eyes vacant. Kull tore the gong from its frame and reeled toward the door. He was a finish fighter; no compromise for him. There would be no bolting the great door upon the horror again. The whole Universe should have halted to watch a man justifying the existence of mankind, scaling sublime heights of glory in his supreme atonement.

He stood in the doorway and leaned against the waves that hung there, hammering ceaselessly. All Hell flowed out to meet him from the frightful thing whose very last stronghold he was invading. All of the Silence was now in the chamber again, forced back by the unconquerable crashings of Sound; Sound concentrated from all the sounds and noises of Earth and imprisoned by the master hand that long ago conquered both Sound and Silence.

And here Silence gathered all its forces for one last attack. Hells of soundless cold and noiseless flame whirled about Kull. Here was a thing, elemental and real. Silence was the absence of sound, Kuthulos had said: Kuthulos who now groveled and yammered empty nothingnesses.

Here was more than an absence, an absence whose utter absence became a presence, an abstract illusion that was a material reality. Kull reeled, blind, stunned, dumb, almost insensible from the onslaught of cosmic forces upon him; soul, body, and mind.

Cloaked by the whirling tentacles, the noise of the gong died out again. But Kull never ceased. His tortured brain rocked, but he thrust his feet against the sill and shoved powerfully forward. He encountered material resistance, like a wave of solid fire, hotter than flame and colder than ice. Still he plunged forward and felt it give—give.

Step by step, foot by foot, he fought his way into the chamber of death, driving the Silence before him. Every step was screaming, demoniac torture; every foot was ravaging Hell. Shoulders hunched, head down, arms rising and falling in jerky rhythm, Kull forced his way, and great drops of blood gathered on his brow and dripped unceasingly.

Behind him, men were beginning to stagger up, weak and dizzy from the Silence that had invaded their brains. They gaped at the door, where the king fought his deathly battle for the Universe. Brule crawled blindly forward, trailing his sword, still dazed, and only following his stunned instinct which bade him follow the king, though the trail led to Hell.

Kull forced the Silence back, step by step, feeling it grow weaker and weaker, feeling it dwindle. Now the sound of the gong pealed out and grew and grew. It filled the room, the Earth, the sky. The Silence cringed before it, and as the Silence dwindled and was forced into itself, it took hideous form that Kull saw, yet did not see. His arm seemed dead, but with a mighty effort he increased his blows. Now the Silence writhed in a dark corner and shrank and shrank.

Again, a last blow! All the sound in the Universe rushed together in one roaring, yelling, shattering, engulfing burst of sound! The gong flew into a million vibrating fragments. And Silence screamed!