Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

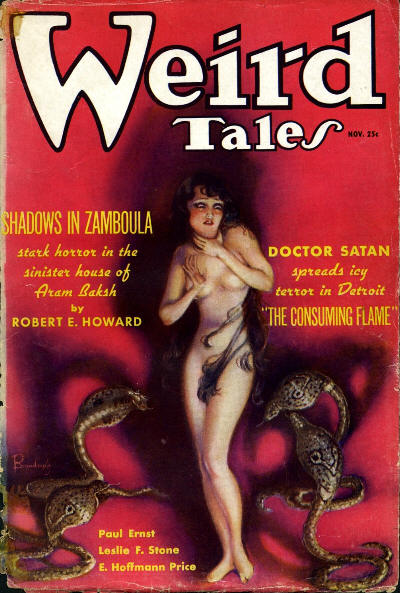

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 26, No. 5 (November 1935).

“Man-Eaters . . .” was Howard’s own title for this story, but it was published under the “Shadows . . .” title.

| I. A Drum Begins II. The Night Skulkers III. Black Hands Gripping |

IV. A Sword-Thrust Through the Curtain Synopsis |

“Peril hides in the house of Aram Baksh!”

The speaker’s voice quivered with earnestness and his lean, black-nailed fingers clawed at Conan’s mightily-muscled arm as he croaked his warning. He was a wiry, sun-burnt man with a straggling black beard, and his ragged garments proclaimed him a nomad. He looked smaller and meaner than ever in contrast to the giant Cimmerian with his black brows, broad breast, and powerful limbs. They stood in a corner of the Sword-Makers’ Bazaar, and on either side of them flowed past the many-tongued, many-colored stream of the Zamboula streets, which is exotic, hybrid, flamboyant and clamorous.

Conan pulled his eyes back from following a bold-eyed, red-lipped Ghanara, whose short slit skirt bared her brown thigh at each insolent step, and frowned down at his importunate companion.

“What do you mean by peril?” he demanded.

The desert man glanced furtively over his shoulder before replying, and lowered his voice.

“Who can say? But desert men and travellers have slept in the house of Aram Baksh, and never been seen or heard of again! What became of them? He swore they rose and went their way—and it is true that no citizen of the city has ever disappeared from his house. But no one saw the travellers again, and men say that goods and equipment recognized as theirs have been seen in the bazaars. If Aram did not sell them, after doing away with their owners, how came them there?”

“I have no goods,” growled the Cimmerian, touching the shagreen-bound hilt of the broadsword that hung at his hip. “I have even sold my horse.”

“But it is not always rich strangers who vanish by night from the house of Aram Baksh!” chattered the Zuagir. “Nay, poor desert men have slept there—because his score is less than that of the other taverns—and have been seen no more! Once a chief of the Zuagirs whose son had thus vanished complained to the satrap, Jungir Khan, who ordered the house searched by soldiers.”

“And they found a cellar full of corpses?” asked Conan in good-humored derision.

“Nay! They found naught! And drove the chief from the city with threats and curses! But—” he drew closer to Conan and shivered, “something else was found! At the edge of the desert, beyond the houses, there is a clump of palm-trees, and within that grove there is a pit. And within that pit have been found human bones, charred and blackened! Not once but many times!”

“Which proves what?” grunted the Cimmerian.

“Aram Baksh is a demon! Nay, in this accursed city which Stygians built and which Hyrkanians rule—where white, brown and black folk mingle together to produce hybrids of all unholy hues and breeds—who can tell who is a man, and who a demon in disguise? Aram Baksh is a demon in the form of a man! At night he assumes his true guise and carries his guests off into the desert where his fellow demons from the waste meet in conclave!”

“Why does he always carry off strangers?” asked Conan skeptically.

“The people of the city would not suffer him to slay their people! But they care naught for the strangers who fall into his hands. Conan, you are of the West, and know not the secrets of this ancient land. But, since the beginning of happenings, the demons of the desert have worshipped Yog, the Lord of the Empty Abodes, with fire—fire that devours human victims!

“Be warned! Thou hast dwelt for many moons in the tents of the Zuagirs, and thou art our brother! Go not to the house of Aram Baksh!”

“Get out of sight!” Conan said suddenly. “Yonder comes a squad of the city-watch. If they see you they may remember a horse that was stolen from the satrap’s stable—”

The Zuagir gasped, and moved convulsively. He ducked between a booth and a stone horse trough, pausing only long enough to chatter: “Be warned, my brother! There are demons in the house of Aram Baksh!” Then he darted down a narrow alley and was gone.

Conan shifted his broad sword-belt to his liking, and calmly returned the searching stares directed at him by the squad of watchmen as they swung past. They eyed him curiously and suspiciously, for he was a man who stood out even in such a motley throng as crowded the winding streets of Zamboula. His blue eyes and alien features distinguished him from the Eastern swarms, and the straight sword at his hip added point to the racial difference.

The watchmen did not accost him, but swung on down the street, while the crowd opened a lane for them. They were Pelishtim, squat, hook-nosed, with blue-black beards sweeping their mailed breasts—mercenaries hired for work the ruling Turanians considered beneath themselves, and no less hated by the mongrel population for that reason.

Conan glanced at the sun, just beginning to dip behind the flat-topped houses on the western side of the bazaar, and hitching once more at his belt, moved off in the direction of Aram Baksh’s tavern.

With a hillman’s stride he moved through the ever-shifting colors of the streets, where the ragged tunics of whining beggars brushed against the ermine-trimmed khalats of lordly merchants, and the pearl-sewn satin of rich courtesans. Giant black slaves slouched along, jostling blue-bearded wanderers from the Shemitish cities, ragged nomads from the surrounding deserts, traders and adventurers from all the lands of the East.

The native population was no less heterogeneous. Here, centuries ago, the armies of Stygia had come, carving an empire out of the eastern desert. Zamboula was but a small trading town then, lying amidst a ring of oases, and inhabited by descendants of nomads. The Stygians built it into a city and settled it with their own people, and with Shemite and Kushite slaves. The ceaseless caravans, threading the desert from east to west and back again, brought riches and more mingling of races. Then came the conquering Turanians, riding out of the East to thrust back the boundaries of Stygia, and now for a generation Zamboula had been Turan’s western-most out-post, ruled by a Turanian satrap.

The babel of a myriad tongues smote on the Cimmerian’s ears as the restless pattern of the Zamboula streets weaved about him—cleft now and then by a squad of clattering horsemen, the tall, supple warriors of Turan, with dark hawk-faces, clinking metal and curved swords. The throng scampered from under their horses’ hoofs, for they were the lords of Zamboula. But tall, somber Stygians, standing back in the shadows, glowered darkly, remembering their ancient glories. The hybrid population cared little whether the king who controlled their destinies dwelt in dark Khemi or gleaming Aghrapur. Jungir Khan ruled Zamboula, and men whispered that Nafertari, the satrap’s mistress, ruled Jungir Khan; but the people went their way, flaunting their myriad colors in the streets, bargaining, disputing, gambling, swilling, loving, as the people of Zamboula have done for all the centuries its towers and minarets have lifted over the sands of the Kharamun.

Bronze lanterns, carven with leering dragons, had been lighted in the streets before Conan reached the house of Aram Baksh. The tavern was the last occupied house on the street, which ran west. A wide garden, enclosed by a wall, where date palms grew thick, separated it from the houses farther east. To the west of the inn stood another grove of palms, through which the street, now become a road, wound out into the desert. Across the road from the tavern stood a row of deserted huts, shaded by straggling palm trees, and occupied only by bats and jackals. As Conan came down the road he wondered why the beggars, so plentiful in Zamboula, had not appropriated these empty houses for sleeping quarters. The lights ceased some distance behind him. Here were no lanterns, except the one hanging before the tavern gate: only the stars, the soft dust of the road underfoot, and the rustle of the palm-leaves in the desert breeze.

Aram’s gate did not open upon the road, but upon the alley which ran between the tavern and the garden of the date-palms. Conan jerked lustily at the rope which depended from the bell beside the lantern, augmenting its clamor by hammering on the iron-bound teak-wood gate with the hilt of his sword. A wicket opened in the gate and a black face peered through.

“Open, blast you,” requested Conan. “I’m a guest. I’ve paid Aram for a room, and a room I’ll have, by Crom!”

The black craned his neck to stare into the starlit road behind Conan; but he opened the gate without comment, and closed it again behind the Cimmerian, locking it and bolting it. The wall was unusually high; but there were many thieves in Zamboula, and a house on the edge of the desert might have to be defended against a nocturnal nomad raid. Conan strode through a garden where great pale blossoms nodded in the starlight, and entered the tap-room, where a Stygian with the shaven head of a student sat at a table brooding over nameless mysteries, and some nondescripts wrangled over a game of dice in a corner.

Aram Baksh came forward, walking softly, a portly man, with a black beard that swept his breast, a jutting hook nose, and small black eyes which were never still.

“You wish food?” he asked. “Drink?”

“I ate a joint of beef and a loaf of bread in the suk,” grunted Conan. “Bring me a tankard of Ghazan wine—I’ve got just enough left to pay for it.” He tossed a copper coin on the wine-splashed board.

“You did not win at the gaming tables?”

“How could I, with only a handful of silver to begin with? I paid you for the room this morning, because I knew I’d probably lose. I wanted to be sure I had a roof over my head tonight. I notice nobody sleeps in the streets in Zamboula. The very beggars hunt a niche they can barricade before dark. The city must be full of a particularly blood-thirsty brand of thieves.”

He gulped the cheap wine with relish, and then followed Aram out of the tap-room. Behind him the players halted their game to stare after him with a cryptic speculation in their eyes. They said nothing, but the Stygian laughed, a ghastly laugh of inhuman cynicism and mockery. The others lowered their eyes uneasily, avoiding each others’ glance. The arts studied by a Stygian scholar are not calculated to make him share the feelings of a normal human being.

Conan followed Aram down a corridor lighted by copper lamps, and it did not please him to note his host’s noiseless tread. Aram’s feet were clad in soft slippers and the hall-way was carpeted with thick Turanian rugs; but there was an unpleasant suggestion of innate stealthiness about the Zamboulan. At the end of the winding corridor Aram halted at a door, across which a heavy iron bar rested in powerful metal brackets. This Aram lifted and showed the Cimmerian into a well appointed chamber, the windows of which, Conan instantly noted, were small and strongly set with twisted bars of iron, tastefully gilded. There were rugs on the floor, a couch, after the Eastern fashion, and ornately carven stools. It was a much more elaborate chamber than Conan could have procured for the price nearer the center of the city—a fact that had first attracted him, when, that morning, he discovered how slim a purse his roisterings for the past few days had left him. He had ridden into Zamboula from the desert a week before.

Aram had lighted a bronze lamp, and he now called Conan’s attention to the two doors. Both were provided with heavy bolts.

“You may sleep safely tonight, Cimmerian,” said Aram, blinking over his bushy beard from the inner doorway. Conan grunted and tossed his naked broadsword on the couch.

“Your bolts and bars are strong; but I always sleep with steel by my side.”

Aram made no reply; he stood fingering his thick beard for a moment as he stared at the grim weapon. Then silently he withdrew, closing the door behind him. Conan shot the bolt into place, crossed the room, opened the opposite door and looked out. The room was on the side of the house that faced the road running west from the city. The door opened into a small court that was enclosed by a wall of its own. The end-walls, which shut it off from the rest of the tavern compound, were high and without entrances; but the wall that flanked the road was low, and there was no lock on the gate.

Conan stood for a moment in the door, the glow of the bronze lamp behind him, looking down the road to where it vanished among the dense palms. Their leaves rustled together in the faint breeze; beyond them lay the naked desert. Far up the street, in the other direction, lights gleamed and the noises of the city came faintly to him. Here was only starlight, the whispering of the palm-leaves, and beyond that low wall, the dust of the road and the deserted huts thrusting their flat roofs against the low stars. Somewhere beyond the palm groves a drum began.

The garbled warnings of the Zuagir returned to him, seeming somehow less fantastic than they had seemed on the crowded, sunlit streets. He wondered again at the riddle of those empty huts. Why did the beggars shun them? He turned back into the chamber, shut the door and bolted it.

The light began to flicker and he investigated, swearing when he found the palm-oil in the lamp was almost exhausted. He started to shout for Aram, then shrugged his shoulders and blew out the light. In the soft darkness he stretched himself fully clad on the couch, his sinewy hand by instinct searching for and closing on the hilt of his broadsword. Glancing idly at the stars framed in the barred windows, with the murmur of the breeze through the palms in his ears, he sank into slumber with a vague consciousness of the muttering drum, out on the desert—the low rumble and mutter of a leather-covered drum, beaten with soft, rhythmic strokes of an open black hand. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

It was the stealthy opening of a door which awakened the Cimmerian. He did not awake as civilized men do, drowsy and drugged and stupid. He awoke instantly, with a clear mind, recognizing the sound that had interrupted his sleep. Lying there tensely in the dark he saw the outer door slowly open. In a widening crack of starlit sky he saw framed a great black bulk—broad stooping shoulders and a misshapen head blocked out against the stars.

Conan felt the skin crawl between his shoulders. He had bolted that door securely. How could it be opening now, save by supernatural agency? And how could a human being possess a head like that outlined against the stars? All the tales he had heard in the Zuagir tents of devils and goblins came back to bead his flesh with clammy sweat. Now the monster slid noiselessly into the room, with a crouching posture and a shambling gait, and a familiar scent assailed the Cimmerian’s nostrils, but did not reassure him, since Zuagir legendry represented demons as smelling like that.

Noiselessly Conan coiled his long legs under him; his naked sword was in his right hand, and when he struck it was as suddenly and murderously as a tiger lunging out of the dark. Not even a demon could have avoided that catapulting charge. His sword met and clove through flesh and bone, and something went heavily to the floor with a strangling cry. Conan crouched in the dark above it, sword dripping in his hand. Devil or beast or man, the thing was dead there on the floor. He sensed death as any wild thing senses it. He glared through the half-open door into the starlit court beyond. The gate stood open, but the court was empty.

Conan shut the door but did not bolt it. Groping in the darkness he found the lamp and lighted it. There was enough oil in it to burn for a minute or so. An instant later he was bending over the figure that sprawled on the floor in a pool of blood.

It was a gigantic black man, naked but for a loin cloth. One hand still grasped a knotty-headed bludgeon. The fellow’s kinky wool was built up into horn-like spindles with twigs and dried mud. This barbaric coiffure had given the head its misshapen appearance in the starlight. Provided with a clue to the riddle, Conan pushed back the thick red lips, and grunted, as he stared down at teeth filed to points.

He understood now the mystery of the strangers who had disappeared from the house of Aram Baksh; the riddle of the black drum thrumming out there beyond the palm groves, and of that pit of charred bones—that pit where strange meat might be roasted under the stars, while black beasts squatted about to glut a hideous hunger. The man on the floor was a cannibal slave from Darfar.

There were many of his kind in the city. Cannibalism was not tolerated openly in Zamboula. But Conan knew now why people locked themselves in so securely at night, and why even beggars shunned the open alleys and doorless ruins. He grunted in disgust as he visualized brutish black shadows skulking up and down the nighted streets, seeking human prey—and such men as Aram Baksh to open the doors to them. The inn-keeper was not a demon, he was worse. The slaves from Darfar were notorious thieves; there was no doubt that some of their pilfered loot found its way into the hands of Aram Baksh. And in return he sold them human flesh.

Conan blew out the light, stepped to the door and opened it, and ran his hand over the ornaments on the outer side. One of them was movable and worked the bolt inside. The room was a trap to catch human prey like rabbits. But this time instead of a rabbit it had caught a saber-toothed tiger.

Conan returned to the other door, lifted the bolt and pressed against it. It was immovable and he remembered the bolt on the other side. Aram was taking no chances either with his victims or the men with whom he dealt. Buckling on his sword-belt, the Cimmerian strode out into the court, closing the door behind him. He had no intention of delaying the settlement of his reckoning with Aram Baksh. He wondered how many poor devils had been bludgeoned in their sleep and dragged out of that room and down the road that ran through the shadowed palm groves to the roasting pit.

He halted in the court. The drum was still muttering, and he caught the reflection of a leaping red glare through the groves. Cannibalism was more than a perverted appetite with the black men of Darfar; it was an integral element of their ghastly cult. The black vultures were already in conclave. But whatever flesh filled their bellies that night, it would not be his.

To reach Aram Baksh he must climb one of the walls which separated the small enclosure from the main compound. They were high, meant to keep out the man-eaters; but Conan was no swamp-bred black man; his thews had been steeled in boyhood on the sheer cliffs of his native hills. He was standing at the foot of the nearer wall when a cry re-echoed under the trees.

In an instant Conan was crouching at the gate, glaring down the road. The sound had come from the shadows of the huts across the road. He heard a frantic choking and gurgling such as might result from a desperate attempt to shriek, with a black hand fastened over the victim’s mouth. A close-knit clump of figures emerged from the shadows beyond the huts, and started down the road—three huge black men carrying a slender, struggling figure between them. Conan caught the glimmer of pale limbs writhing in the starlight, even as, with a convulsive wrench, the captive slipped from the grasp of the brutal fingers and came flying up the road, a supple young woman, naked as the day she was born. Conan saw her plainly before she ran out of the road and into the shadows between the huts. The blacks were at her heels, and back in the shadows the figures merged and an intolerable scream of anguish and horror rang out.

Stirred to red rage by the ghoulishness of the episode, Conan raced across the road.

Neither victim nor abductors were aware of his presence until the soft swish of the dust about his feet brought them about, and then he was almost upon them, coming with the gusty fury of a hill wind. Two of the blacks turned to meet him, lifting their bludgeons. But they failed to properly estimate the speed at which he was coming. One of them was down, disembowelled, before he could strike, and wheeling catlike, Conan evaded the stroke of the other’s cudgel, and lashed in a whistling counter-cut. The black’s head flew into the air; the headless body took three staggering steps, spurting blood and clawing horribly at the air with groping hands, and then slumped to the dust.

The remaining cannibal gave back with a strangled yell, hurling his captive from him. She tripped and rolled in the dust, and the black fled in blind panic, toward the direction of the city. Conan was at his heels. Fear winged the black feet, but before they reached the eastern-most hut, he sensed death at his back, and bellowed like an oxen in the slaughter-yards.

“Black dog of hell!” Conan drove his sword between the dusky shoulders with such vengeful fury that the broad blade stood out half its length from the black breast. With a choking cry the black stumbled headlong, and Conan braced his feet and dragged out his sword as his victim fell.

Only the breeze disturbed the leaves. Conan shook his head as a lion shakes its mane and growled his unsatiated blood-lust. But no more shapes slunk from the shadows, and before the huts the starlit road stretched empty. He whirled at the quick patter of feet behind him, but it was only the girl, rushing to throw herself on him and clasp his neck in a desperate grasp, frantic from terror of the abominable fate she had just escaped.

“Easy, girl,” he grunted. “You’re all right. How did they catch you?”

She sobbed something unintelligible. He forgot all about Aram Baksh as he scrutinized her by the light of the stars. She was white, though a very definite brunet, obviously one of Zamboula’s many mixed breeds. She was tall, with a slender, supple form as he was in a good position to observe. Admiration burned in his fierce eyes as he looked down on her splendid bosom and her lithe limbs which still quivered from fright and exertion. He passed an arm about her flexible waist and said, reassuringly: “Stop shaking, wench; you’re safe enough.”

His touch seemed to restore her shaken sanity. She tossed back her thick, glossy locks and cast a fearful glance over her shoulder, while she pressed closer to the Cimmerian as if seeking security in the contact.

“They caught me in the streets,” she muttered, shuddering. “Lying in wait, beneath a dark arch—black men, like great, hulking apes! Set have mercy on me! I shall dream of it!”

“What were you doing out on the streets this time of night?” he inquired, fascinated by the satiny feel of her sleek skin under his questing fingers.

She raked back her hair and stared blankly up into his face. She did not seem aware of his caresses.

“My lover,” she said. “My lover drove me into the streets. He went mad and tried to kill me. As I fled from him I was seized by those beasts.”

“Beauty like yours might drive a man mad,” quoth Conan, running his fingers experimentally through her glossy tresses.

She shook her head, like one emerging from a daze. She no longer trembled, and her voice was steady.

“It was the spite of a priest—of Totrasmek, the high priest of Hanuman, who desires me for himself—the dog!”

“No need to curse him for that,” grinned Conan. “The old hyena has better taste than I thought.”

She ignored the bluff compliment. She was regaining her poise swiftly.

“My lover is a—a young Turanian soldier. To spite me, Totrasmek gave him a drug that drove him mad. Tonight he snatched up a sword and came at me to slay me in his madness, but I fled from him into the streets. The negroes seized me and brought me to this—what was that?”

Conan had already moved. Soundlessly as a shadow he drew her behind the nearest hut, beneath the straggling palms. They stood in tense stillness, while the low mutterings both had heard grew louder until voices were distinguishable. A group of negroes, some nine or ten, were coming along the road from the direction of the city. The girl clutched Conan’s arm and he felt the terrified quivering of her supple body against his.

Now they could understand the gutturals of the black men.

“Our brothers are already assembled at the pit,” said one. “We have had no luck. I hope they have enough for us.”

“Aram promised us a man,” muttered another, and Conan mentally promised Aram something.

“Aram keeps his word,” grunted yet another. “Many a man we have taken from his tavern. But we pay him well. I myself have given him ten bales of silk I stole from my master. It was good silk, by Set!”

The blacks shuffled past, bare splay feet scuffing up the dust, and their voices dwindled down the road.

“Well for us those corpses are lying behind these huts,” muttered Conan. “If they look in Aram’s death-room they’ll find another. Let’s begone.”

“Yes, let us hasten!” begged the girl, almost hysterical again. “My lover is wandering somewhere in the streets alone. The negroes may take him.”

“A devil of a custom, this is,” growled Conan, as he led the way toward the city, paralleling the road, but keeping behind the huts and straggling trees. “Why don’t the citizens clean out these black dogs?”

“They are valuable slaves,” murmured the girl. “There are so many of them they might revolt if they were denied the flesh for which they lust. The people of Zamboula know they skulk the streets at night, and all are careful to remain within locked doors, except when something unforeseen happens, as it did to me. The blacks prey on anything they catch, but they seldom catch anybody but strangers. The people of Zamboula are not concerned with the strangers that pass through the city.

“Such men as Aram Baksh sell these strangers to the blacks. He would not dare attempt such a thing with a citizen.”

Conan spat in disgust, and a moment later led his companion out into the road which was becoming a street, with still, unlighted houses on each side. Slinking in the shadows was not congenial to his nature.

“Where do you want to go?” he asked. The girl did not seem to object to his arm about her waist.

“To my house, to rouse my servants,” she answered. “To bid them search for my lover. I do not wish the city—the priests—anyone—to know of his madness. He—he is a young officer with a promising future. Perhaps we can drive this madness from him if we can find him.”

“If we find him?” rumbled Conan. “What makes you think I want to spend the night scouring the streets for a lunatic?”

She cast a quick glance into his face, and properly interpreted the gleam in his blue eyes. Any woman could have known that he would follow her wherever she led—for awhile, at least. But being a woman she concealed her knowledge of that fact.

“Please—” she began with a hint of tears in her voice. “I have no one else to ask for help—you have been kind—”

“All right,” he grunted. “All right! What’s the young reprobate’s name?”

“Why—Alafdhal. I am Zabibi, a dancing girl. I have danced often before the satrap, Jungir Khan, and his mistress Nafertari, and before all the lords and royal ladies of Zamboula. Totrasmek desired me, and because I repulsed him, he made me the innocent tool of his vengeance against Alafdhal. I asked a love potion of Totrasmek, not suspecting the depth of his guile and hate. He gave me a drug to mix with my lover’s wine, and he swore that when Alafdhal drank it, he would love me even more madly than ever, and grant my every wish. I mixed the drug secretly with my lover’s wine. But having drunk, my lover went raving mad and things came about as I have told you. Curse Totrasmek, the hybrid snake—ahhh!”

She caught his arm convulsively and both stopped short. They had come into a district of shops and stalls, all deserted and unlighted, for the hour was late. They were passing an alley, and in its mouth a man was standing, motionless and silent. His head was lowered, but Conan caught the weird gleam of eery eyes regarding them unblinkingly. His skin crawled, not with fear of the sword in the man’s hand, but because of the uncanny suggestion of his posture and silence. They suggested madness. Conan pushed the girl aside and drew his sword.

“Don’t kill him!” she begged. “In the name of Set, do not slay him! You are strong—overpower him!”

“We’ll see,” he muttered, grasping his sword in his right hand and clenching his left into a mallet-like fist.

He took a wary step toward the alley—and with a horrible moaning laugh the Turanian charged. As he came he swung his sword, rising on his toes as he put all the power of his body behind the blows. Sparks flashed blue as Conan parried the blade, and the next instant the madman was stretched senseless in the dust from a thundering buffet of Conan’s left fist.

The girl ran forward.

“Oh, he is not—he is not—”

Conan bent swiftly, turned the man on his side and ran quick fingers over him.

“He’s not hurt much,” he grunted. “Bleeding at the nose, but anybody’s likely to do that, after a clout on the jaw. He’ll come to after a bit, and maybe his mind will be right. In the meantime I’ll tie his wrists with his sword-belt—so. Now where do you want me to take him?”

“Wait!” She knelt beside the senseless figure, seized the bound hands and scanned them avidly. Then, shaking her head as if in baffled disappointment, she rose. She came close to the giant Cimmerian, and laid her slender hands on his arching breast. Her dark eyes, like wet black jewels in the starlight, gazed up into his.

“You are a man! Help me! Totrasmek must die! Slay him for me!”

“And put my neck into a Turanian noose?” he grunted.

“Nay!” The slender arms, strong as pliant steel, were around his corded neck. Her supple body throbbed against his. “The Hyrkanians have no love for Totrasmek. The priests of Set fear him. He is a mongrel, who rules men by fear and superstition. I worship Set, and the Turanians bow to Erlik, but Totrasmek sacrifices to Hanuman the accursed! The Turanian lords fear his black arts and his power over the hybrid population, and they hate him. Even Jungir Khan and his mistress Nafertari fear and hate him. If he were slain in his temple at night, they would not seek his slayer very closely.”

“And what of his magic?” rumbled the Cimmerian.

“You are a fighting man,” she answered. “To risk your life is part of your profession.”

“For a price,” he admitted.

“There will be a price!” she breathed, rising on tip-toes, to gaze into his eyes. The nearness of her vibrant body drove a flame through his veins. The perfume of her breath mounted to his brain. But as his arms closed about her supple figure she avoided them with a lithe movement, saying: “Wait! First serve me in this matter.”

“Name your price.” He spoke with some difficulty.

“Pick up my lover,” she directed, and the Cimmerian stooped and swung the tall form easily to his broad shoulder. At the moment he felt as if he could have toppled over Jungir Khan’s palace with equal ease. The girl murmured an endearment to the unconscious man, and there was no hypocrisy in her attitude. She obviously loved Alafdhal sincerely. Whatever business arrangement she made with Conan would have no bearing on her relationship with Alafdhal. Women are more practical about these things than men. What Alafdhal never knew would not hurt him.

“Follow me!” She hurried along the street, while the Cimmerian strode easily after her, in no way discomforted by his limp burden. He kept a wary eye out for black shadows skulking under arches, but saw nothing suspicious. Doubtless the men of Darfar were all gathered at the roasting pit. The girl turned down a narrow side street, and presently knocked cautiously at an arched door.

Almost instantly a wicket opened in the upper panel, and a black face glanced out. She bent close to the opening, whispering swiftly. Bolts creaked in their sockets, and the door opened. A giant black man stood framed against the soft glow of a copper lamp. A quick glance showed Conan the man was not from Darfar. His teeth were unfiled and his kinky hair was cropped close to his skull. He was from the Wadai.

At a word from Zabibi Conan gave the limp body into the black’s arms, and saw the young officer laid on a velvet divan. He showed no signs of returning consciousness. The blow that had rendered him senseless might have felled an ox. Zabibi bent over him for an instant, her fingers nervously twining and twisting. Then she straightened and beckoned the Cimmerian.

The door closed softly, the locks clicked behind them, and the closing wicket shut off the glow of the lamps. In the starlight of the street Zabibi took Conan’s hand. Her own hand trembled a little.

“You will not fail me?”

He shook his maned head, massive against the stars.

“Then follow me to Hanuman’s shrine, and the gods have mercy on our souls!”

Along the silent streets they moved like phantoms of antiquity. They went in silence. Perhaps the girl was thinking of her lover lying senseless on the divan under the copper lamps; or was shrinking with fear of what lay ahead of them in the demon-haunted shrine of Hanuman. The barbarian was thinking only of the woman moving so supply beside him. The perfume of her scented hair was in his nostrils, the sensuous aura of her presence filled his brain and left room for no other thoughts.

Once they heard the clank of brazen-shod feet, and drew into the shadows of a gloomy arch while a squad of Pelishtim watchmen swung past. There were fifteen of them; they marched in close formation, pikes at the ready, and the rearmost men had their broad brass shields slung on their backs, to protect them from a knife-stroke from behind. The skulking menace of the black man-eaters was a threat even to armed men.

As soon as the clang of their sandals had receded up the street, Conan and the girl emerged from their hiding place and hurried on. A few moments later they saw the squat, flat-topped edifice they sought looming ahead of them.

The temple of Hanuman stood alone in the midst of a broad square, which lay silent and deserted beneath the stars. A marble wall surrounded the shrine, with a broad opening directly before the portico. This opening had no gate or any sort of barrier.

“Why don’t the blacks seek their prey here?” muttered Conan. “There’s nothing to keep them out of the temple.”

He could feel the trembling of Zabibi’s body as she pressed close to him.

“They fear Totrasmek, as all in Zamboula fear him, even Jungir Khan and Nafertari. Come! Come quickly, before my courage flows from me like water!”

The girl’s fear was evident, but she did not falter. Conan drew his sword and strode ahead of her as they advanced through the open gateway. He knew the hideous habits of the priests of the East, and was aware that an invader of Hanuman’s shrine might expect to encounter almost any sort of nightmare horror. He knew there was a good chance that neither he nor the girl would ever leave the shrine alive, but he had risked his life too many times before to devote much thought to that consideration.

They entered a court paved with marble which gleamed whitely in the starlight. A short flight of broad marble steps led up to the pillared portico. The great bronze doors stood wide open as they had stood for centuries. But no worshippers burnt incense within. In the day men and women might come timidly into the shrine and place offerings to the ape-god on the black altar. At night the people shunned the temple of Hanuman as hares shun the lair of the serpent. Burning censers bathed the interior in a soft weird glow that created an illusion of unreality. Near the rear wall, behind the black stone altar, sat the god with his gaze fixed for ever on the open door, through which for centuries his victims had come, dragged by chains of roses. A faint groove ran from the sill to the altar, and when Conan’s foot felt it, he stepped away as quickly as if he had trodden upon a snake. That groove had been worn by the faltering feet of the multitude of those who had died screaming on that grim altar.

Bestial in the uncertain light Hanuman leered with his carven mask. He sat, not as an ape would crouch, but cross-legged as a man would sit, but his aspect was no less simian for that reason. He was carved from black marble, but his eyes were rubies, which glowed red and lustful as the coals of hell’s deepest pits. His great hands lay upon his lap, palms upward, taloned fingers spread and grasping. In the gross emphasis of his attributes, in the leer of his satyr-countenance, was reflected the abominable cynicism of the degenerate cult which deified him.

The girl moved around the image, making toward the back wall, and when her sleek flank brushed against a carven knee, she shrank aside and shuddered as if a reptile had touched her. There was a space of several feet between the broad back of the idol and the marble wall with its frieze of gold leaves. On either hand, flanking the idol, an ivory door under a gold arch was set in the wall.

“Those doors open into each end of a hair-pin shaped corridor,” she said hurriedly. “Once I was in the interior of the shrine—once!” She shivered and twitched her slim shoulders at a memory both terrifying and obscene. “The corridor is bent like a horseshoe, with each horn opening into this room. Totrasmek’s chambers are enclosed within the curve of the corridor and open into it. But there is a secret door in this wall which opens directly into an inner chamber—”

She began to run her hands over the smooth surface, where no crack or crevice showed. Conan stood beside her, sword in hand, glancing warily about him. The silence, the emptiness of the shrine, with imagination picturing what might lie behind that wall, made him feel like a wild beast nosing a trap.

“Ah!” The girl had found a hidden spring at last; a square opening gaped blackly in the wall. Then: “Set!” she screamed, and even as Conan leaped toward her, he saw that a great misshapen hand had fastened itself in her hair. She was snatched off her feet and jerked headfirst through the opening. Conan, grabbing ineffectually at her, felt his fingers slip from a naked limb, and in an instant she had vanished and the wall showed blank as before. Only from beyond it came briefly the muffled sounds of a struggle, a scream, faintly heard, and a low laugh that made Conan’s blood congeal in his veins.

With an oath the Cimmerian smote the wall a terrific blow with the pommel of his sword, and the marble cracked and chipped. But the hidden door did not give way, and reason told him that doubtless it had been bolted on the other side of the wall. Turning, he sprang across the chamber to one of the ivory doors.

He lifted his sword to shatter the panels, but on a venture tried the door first with his left hand. It swung open easily, and he glared into a long corridor that curved into dimness under the weird light of censers similar to those in the shrine. A heavy gold bolt showed on the jamb of the door, and he touched it lightly with his finger tips. The faint warmness of the metal could have been detected only by a man whose faculties were akin to those of a wolf. That bolt had been touched—and therefore drawn—within the last few seconds. The affair was taking on more and more of the aspect of a baited trap. He might have known Totrasmek would know when anyone entered the temple.

To enter the corridor would undoubtedly be to walk into whatever trap the priest had set for him. But Conan did not hesitate. Somewhere in that dim-lit interior Zabibi was a captive, and, from what he knew of the characteristics of Hanuman’s priests, he was sure that she needed help badly. Conan stalked into the corridor with a pantherish tread, poised to strike right or left.

On his left ivory, arched doors opened into the corridor, and he tried each in turn. All were locked. He had gone perhaps seventy-five feet when the corridor bent sharply to the left, describing the curve the girl had mentioned. A door opened into this curve, and it gave under his hand.

He was looking into a broad square chamber, somewhat more clearly lighted than the corridor. Its walls were of white marble, the floor of ivory, the ceiling of fretted silver. He saw divans of rich satin, gold-worked footstools of ivory, a disk-shaped table of some massive, metal-like substance. On one of the divans a man was reclining, looking toward the door. He laughed as he met the Cimmerian’s startled glare.

This man was naked except for a loin cloth and high-strapped sandals. He was brown-skinned, with close-cropped black hair and restless black eyes that set off a broad arrogant face. In girth and breadth he was enormous, with huge limbs on which the great muscles swelled and rippled at each slightest movement. His hands were the largest Conan had ever seen. The assurance of gigantic physical strength colored his every action and inflection.

“Why not enter, barbarian?” he called mockingly, with an exaggerated gesture of invitation. Conan’s eyes began to smolder ominously, but he trod warily into the chamber, his sword ready.

“Who the devil are you?” he growled.

“I am Baal-pteor,” the man answered. “Once, long ago and in another land, I had another name. But this is a good name, and why Totrasmek gave it to me, any temple-wench can tell you.”

“So you’re his dog,” grunted Conan. “Well, curse your brown hide, Baal-pteor, where’s the wench you jerked through the wall?”

“My master entertains her!” laughed Baal-pteor. “Listen!”

From beyond a door opposite the one by which Conan had entered there sounded a woman’s scream, faint and muffled in the distance.

“Blast your soul!” Conan took a stride toward the door, then wheeled with his skin tingling. Baal-pteor was laughing at him, and that laugh was edged with menace that made the hackles rise on Conan’s neck and sent an answering red wave of murder-lust driving across his vision.

He started toward Baal-pteor, the knuckles on his sword-hand showing white. With a swift motion the brown man threw something at him—a shining crystal sphere that glistened in the weird light.

Conan dodged instinctively, but, miraculously, the globe stopped short in mid-air, a few feet from his face. It did not fall to the floor. It hung suspended, as if by invisible filaments, some five feet above the floor. And as he glared in amazement, it began to rotate with growing speed. And as it revolved it grew, it expanded, it became nebulous. It filled the chamber. It enveloped him. It blotted out furniture, walls, the smiling countenance of Baal-pteor. He was lost in the midst of a blinding bluish blur of whirling speed. Terrific winds screamed past Conan, tugging, tearing at him, striving to wrench him from his feet, to drag him into the vortex that spun madly before him.

With a choking cry Conan lurched backward, reeled, felt the solid wall against his back. At the contact the illusion ceased to be. The whirling, titanic sphere vanished like a bursting bubble. Conan reeled upright in the silver-ceilinged room, with a grey mist coiling about his feet, and saw Baal-pteor lolling on the divan, shaking with silent laughter.

“Son of a slut!” Conan lunged at him. But the mist swirled up from the floor, blotting out that giant brown form. Groping in a rolling cloud that blinded him, Conan felt a rending sensation of dislocation—and then room and mist and brown man were gone together. He was standing alone among the high reeds of a marshy fen, and a buffalo was lunging at him, head down. He leaped aside from the ripping scimitar-curved horns, and drove his sword in behind the foreleg, through ribs and heart. And then it was not a buffalo dying there in the mud, but the brown-skinned Baal-pteor. With a curse Conan struck off his head, and the head soared from the ground and snapped beast-like tusks into his throat. For all his mighty strength he could not tear it loose—he was choking—strangling—then there was a rush and roar through space, the dislocating shock of an immeasurable impact, and he was back in the chamber with Baal-pteor, his head once more set firmly on his shoulders, laughing silently at him from the divan.

“Mesmerism!” muttered Conan, crouching and digging his toes hard against the marble. His eyes blazed. This brown dog was playing with him, making sport of him! But this mummery, this child’s play of mists and shadows of thought, it could not harm him. He had but to leap and strike and the brown acolyte would be a mangled corpse under his heel. This time he would not be fooled by shadows of illusion—but he was.

A blood-curdling snarl behind him, and he wheeled and struck in a flash at the panther crouching to spring on him from the metal-colored table. Even as he struck the apparition vanished and his blade clashed deafeningly on the adamantine surface. Instantly he sensed something abnormal. The blade stuck to the table! He wrenched at it savagely. It did not give. This was no mesmeristic trick. The table was a giant magnet. He gripped the hilt with both hands, when a voice at his shoulder brought him about, to face the brown man who had at last risen from the divan.

Slightly taller than Conan, and much heavier, Baal-pteor loomed before him, a daunting image of muscular development. His mighty arms were unnaturally long, and his great hands opened and closed, twitching convulsively. Conan released the hilt of his imprisoned sword and fell silent, watching his enemy through slitted lids.

“Your head, Cimmerian!” taunted Baal-pteor. “I shall take, with my bare hands, twisting it from your shoulders as the head of a fowl is twisted! Thus the sons of Kosala offer sacrifice to Yajur! Barbarian, you looked upon a Strangler of Yota-pong! I was chosen by the priests of Yajur in my infancy, and throughout childhood, boyhood and youth, I was trained in the art of slaying with the naked hands—for only thus are the sacrifices enacted. Yajur loves blood, and we waste not a drop from the victim’s veins! When I was a child they gave me infants to throttle; when I was a boy I strangled young girls; as a youth, women, old men and young boys. Not until I reached my full manhood was I given a strong man to slay on the altar of Yota-pong.

“For years I offered the sacrifices to Yajur. Hundreds of necks have snapped between these fingers—” he worked them before the Cimmerian’s angry eyes. “Why I fled from Yota-pong to become Totrasmek’s servant is no concern of yours. In a moment you will be beyond curiosity. The priests of Kosala, the Stranglers of Yajur, are strong beyond the belief of men. And I was stronger than any. With my hands, barbarian, I shall break your neck!”

And like the stroke of twin cobras, the great hands closed on Conan’s throat. The Cimmerian made no attempt to dodge or fend them away, but his own hands darted to the Kosalan’s bull-neck. Baal-pteor’s black eyes widened as he felt the thick cords of muscles that protected the barbarian’s throat. With a snarl he exerted his inhuman strength, and knots and lumps and ropes of thews rose along his massive arms. And then a choking gasp burst from him as Conan’s fingers locked on his throat. For an instant they stood there like statues, their faces masks of effort, veins beginning to stand out purply on their temples. Conan’s thin lips drew back from his teeth in a grinning snarl. Baal’s eyes were distended; in them grew an awful surprize and the glimmer of fear. They stood motionless as images, except for the expanding of their muscles on rigid arms and braced legs, but strength beyond common conception was warring there—strength that might have uprooted trees and crushed the skulls of bullocks.

The wind whistled suddenly from between Baal-pteor’s parted teeth. His face was growing purple. Fear flooded his eyes. His thews seemed ready to burst from his arms and shoulders, yet the muscles of the Cimmerian’s thick neck did not give, they felt like masses of woven iron cords under his desperate fingers. But his own flesh was giving way under the iron fingers of the Cimmerian which ground deeper and deeper into the yielding throat-muscles, crushing them in upon jugular and wind-pipe.

The statuesque immobility of the group gave way to sudden, frenzied motion, as the Kosalan began to wrench and heave, seeking to throw himself backward. He let go of Conan’s throat and grasped his wrists, trying to tear away those inexorable fingers.

With a sudden lunge Conan bore him backward until the small of his back crashed against the table. And still farther over its edge Conan bent him, back and back, until his spine was ready to snap.

Conan’s low laugh was merciless as the ring of steel.

“You fool!” he all but whispered. “I think you never saw a man from the West before. Did you deem yourself strong, because you were able to twist the heads off civilized folk, poor weaklings with muscles like rotten string? Hell! Break the neck of a wild Cimmerian bull before you call yourself strong. I did that, before I was a full-grown man—like this!”

And with a savage wrench he twisted Baal-pteor’s head around until the ghastly face leered over the left shoulder, and the vertebrae snapped like a rotten branch.

Conan hurled the flopping corpse to the floor, turned to the sword again and gripped the hilt with both hands, bracing his feet against the floor. Blood trickled down his broad breast from the wounds Baal-pteor’s finger nails had torn in the skin of his neck. His black hair was damp, sweat ran down his face, and his chest heaved. For all his vocal scorn of Baal-pteor’s strength, he had almost met his match in the inhuman Kosalan. But without pausing to catch his breath, he exerted all his strength in a mighty wrench that tore the sword from the magnet where it clung. Another instant and he had pushed open the door from behind which the scream had sounded, and was looking down a long straight corridor, lined with ivory doors. The other end was masked by a rich velvet curtain, and from beyond that curtain came the devilish strains of such music as Conan had never heard, not even in nightmares. It made the short hairs bristle on the back of his neck. Mingled with it was the panting, hysterical sobbing of a woman. Grasping his sword firmly, he glided down the corridor.

When Zabibi was jerked headfirst through the aperture which opened in the wall behind the idol, her first, dizzy, disconnected thought was that her time had come. She instinctively shut her eyes and waited for the blow to fall. But instead she felt herself dumped unceremoniously onto the smooth marble floor which bruised her knees and hip. Opening her eyes she stared fearfully around her, just as a muffled impact sounded from beyond the wall. She saw a brown-skinned giant in a loin-cloth standing over her, and, across the chamber into which she had come, a man sat on a divan, with his back to a rich black velvet curtain, a broad, fleshy man, with fat white hands and snaky eyes. And her flesh crawled, for this man was Totrasmek, the priest of Hanuman, who for years had spun his slimy webs of power throughout the city of Zamboula.

“The barbarian seeks to batter his way through the wall,” said Totrasmek sardonically, “but the bolt will hold.”

The girl saw that a heavy golden bolt had been shot across the hidden door, which was plainly discernible from this side of the wall. The bolt and its sockets would have resisted the charge of an elephant.

“Go open one of the doors for him, Baal-pteor,” ordered Totrasmek. “Slay him in the square chamber at the other end of the corridor.”

The Kosalan salaamed and departed by the way of a door in the side wall of the chamber. Zabibi rose, staring fearfully at the priest, whose eyes ran avidly over her splendid figure. To this she was indifferent. A dancer of Zamboula was accustomed to nakedness. But the cruelty in his eyes started her limbs to quivering.

“Again you come to me in my retreat, beautiful one,” he purred with cynical hypocrisy. “It is an unexpected honor. You seemed to enjoy your former visit so little, that I dared not hope for you to repeat it. Yet I did all in my power to provide you with an interesting experience.”

For a Zamboula dancer to blush would be an impossibility, but a smolder of anger mingled with the fear in Zabibi’s dilated eyes.

“Fat pig! You know I did not come here for love of you.”

“No,” laughed Totrasmek, “you came like a fool, creeping through the night with a stupid barbarian to cut my throat! Why should you seek my life?”

“You know why!” she cried, knowing the futility of trying to dissemble.

“You are thinking of your lover,” he laughed. “The fact that you are here seeking my life shows that he quaffed the drug I gave you. Well, did you not ask for it? And did I not send what you asked for, out of the love I bear you?”

“I asked you for a drug that would make him slumber harmlessly for a few hours,” she said bitterly. “And you—you sent your servant with a drug that drove him mad! I was a fool ever to trust you. I might have known your protestations of friendship were lies, to disguise your hate and spite.”

“Why did you wish your lover to sleep?” he retorted. “So you could steal from him the only thing he would never give you—the ring with the jewel men call the Star of Khorala—the star stolen from the queen of Ophir, who would pay a roomful of gold for its return. He would not give it to you willingly, because he knew that it holds a magic which, when properly controlled, will enslave the hearts of any of the opposite sex. You wished to steal it from him fearing that his magicians would discover the key to that magic, and he would forget you in his conquests of the queens of the world. You would sell it back to the queen of Ophir, who understands its power and would use it to enslave men, as she did before it was stolen.”

“And why did you want it?” she demanded sulkily.

“I understand its powers. It would increase the power of my arts.”

“Well,” she snapped, “you have it now!”

“I have the Star of Khorala? Nay, you err.”

“Why bother to lie?” she retorted bitterly. “He had it on his finger when he drove me into the streets. He did not have it when I found him again. Your servant must have been watching the house, and have taken it from him, after I escaped him. To the devil with it! I want my lover back sane and whole. You have the ring; you have punished us both. Why do you not restore his mind to him? Can you?”

“I could,” he assured her, in evident enjoyment of her distress. He drew a phial from among his robes. “This contains the juice of the golden lotus. If your lover drank it he would be sane again. Yes, I will be merciful. You have both thwarted and flouted me, not once but many times; he has constantly opposed my wishes. But I will be merciful. Come and take the phial from my hand.”

She stared at Totrasmek, trembling with eagerness to seize it, but fearing it was but some cruel jest. She advanced timidly, with a hand extended, and he laughed heartlessly and drew back out of her reach. Even as her lips parted to curse him, some instinct snatched her eyes upward. From the gilded ceiling four jade-hued vessels were falling. She dodged, but they did not strike her. They crashed to the floor about her, forming the four corners of a square. And she screamed, and screamed again. For out of each ruin reared the hooded head of a cobra, and one struck at her bare leg. Her convulsive movement to evade it brought her within reach of the one on the other side and again she had to shift like lightning to avoid the flash of its hideous head.

She was caught in a frightful trap. All four serpents were swaying and striking at foot, ankle, calf, knee, thigh, hip, whatever portion of her voluptuous body chanced to be nearest to them, and she could not spring over them or pass between them to safety. She could only whirl and spring aside and twist her body to avoid the strokes, and each time she moved to dodge one snake, the motion brought her within range of another, so that she had to keep shifting with the speed of light. She could move only a short space in any direction, and the fearful hooded crests were menacing her every second. Only a dancer of Zamboula could have lived in that grisly square.

She became, herself, a blur of bewildering motion. The heads missed her by hair’s breadths, but they missed, as she pitted her twinkling feet, flickering limbs, and perfect eye against the blinding speed of the scaly monsters her enemy had conjured out of thin air.

Somewhere a thin whining music struck up, mingling with the hissing of the serpents, like an evil nightwind blowing through the empty sockets of a skull. Even in the flying speed of her urgent haste she realized that the darting of the serpents was no longer at random. They obeyed the grisly piping of the eery music. They struck with a horrible rhythm, and perforce her swaying, writhing, spinning body attuned itself to their rhythm. Her frantic motions melted into the measures of a dance compared to which the most obscene tarantella of Zamora would have seemed sane and restrained. Sick with shame and terror Zabibi heard the hateful mirth of her merciless tormentor.

“The Dance of the Cobras, my lovely one!” laughed Totrasmek. “So maidens danced in the sacrifice to Hanuman centuries ago—but never with such beauty and suppleness. Dance, girl, dance! How long can you avoid the fangs of the Poison People? Minutes? Hours? You will weary at last. Your swift, sure feet will stumble, your legs falter, your hips slow in their rotations. Then the fangs will begin to sink deep into your ivory flesh—”

Behind him the curtain shook as if struck by a gust of wind, and Totrasmek screamed. His eyes dilated and his hands caught convulsively at the length of bright steel which jutted suddenly from his breast.

The music broke off short. The girl swayed dizzily in her dance, crying out in dreadful anticipation of the flickering fangs—and then only four wisps of harmless blue smoke curled up from the floor about her, as Totrasmek sprawled headlong from the divan.

Conan came from behind the curtain, wiping his broad blade. Looking through the hangings he had seen the girl dancing desperately between four swaying spirals of smoke, but he had guessed that their appearance was very different to her. He knew he had killed Totrasmek.

Zabibi sank down on the floor, panting, but even as Conan started toward her, she staggered up again, though her legs trembled with exhaustion.

“The phial!” she gasped. “The phial!”

Totrasmek still grasped it in his stiffening hand. Ruthlessly she tore it from his locked fingers, and then began frantically to ransack his garments.

“What the devil are you looking for?” Conan demanded.

“A ring—he stole it from Alafdhal. He must have, while my lover walked in madness through the streets. Set’s devils!”

She had convinced herself that it was not on the person of Totrasmek. She began to cast about the chamber, tearing up divan covers and hangings, and upsetting vessels.

She paused and raked a damp lock of hair out of her eyes.

“I forgot Baal-pteor!”

“He’s in hell with his neck broken,” Conan assured her.

She expressed vindictive gratification at the news, but an instant later swore expressively.

“We can’t stay here. It’s not many hours until dawn. Lesser priests are likely to visit the temple at any hour of the night, and if we’re discovered here with his corpse, the people will tear us to pieces. The Turanians could not save us.”

She lifted the bolt on the secret door, and a few moments later they were in the streets and hurrying away from the silent square where brooded the age-old shrine of Hanuman.

In a winding street a short distance away Conan halted and checked his companion with a heavy hand on her naked shoulder.

“Don’t forget there was a price—”

“I have not forgotten!” She twisted free. “But we must go to—to Alafdhal first!”

A few minutes later the black slave let them through the wicket door. The young Turanian lay upon the divan, his arms and legs bound with heavy velvet ropes. His eyes were open, but they were like those of a mad dog, and foam was thick on his lips. Zabibi shuddered.

“Force his jaws open!” she commanded, and Conan’s iron fingers accomplished the task. Zabibi emptied the phial down the maniac’s gullet. The effect was like magic. Instantly he became quiet. The glare faded from his eyes; he stared up at the girl in a puzzled way, but with recognition and intelligence. Then he fell into a normal slumber.

“When he awakes he will be quite sane,” she whispered, motioning to the silent slave. With a deep bow he gave into her hands a small leathern bag, and drew about her shoulders a silken cloak. Her manner had subtly changed when she beckoned Conan to follow her out of the chamber.

In an arch that opened on the street, she turned to him, drawing herself up with a new regality.

“I must now tell you the truth,” she said. “I am not Zabibi. I am Nafertari. And he is not Alafdhal, a poor captain of the guardsmen. He is Jungir Khan, satrap of Zamboula.”

Conan made no comment; his scarred dark countenance was immobile.

“I lied to you because I dared not divulge the truth to anyone,” she said. “We were alone when Jungir Khan went mad. None knew of it but myself. Had it been known that the satrap of Zamboula was a madman, there would have been instant revolt and rioting, even as Totrasmek planned, who plotted our destruction.

“You see now how impossible is the reward for which you hoped. The satrap’s mistress is not—can not be for you. But you shall not go unrewarded. Here is a sack of gold.” She gave him the bag she had received from the slave.

“Go, now, and when the sun is up come to the palace. I will have Jungir Khan make you captain of his guard. But you will take your orders from me, secretly. Your first duty will be to march a squad to the shrine of Hanuman, ostensibly to search for clues of the priest’s slayer; in reality to search for the Star of Khorala. It must be hidden there somewhere. When you find it, bring it to me. You have my leave to go now.”

He nodded, still silent, and strode away. The girl, watching the swing of his broad shoulders, was piqued to note that there was nothing in his bearing to show that he was in any way chagrined or abashed.

When he had rounded a corner, he glanced back, and then changed his direction and quickened his pace. A few moments later he was in the quarter of the city containing the Horse Market. There he smote on a door until from the window above a bearded head was thrust to demand the reason for the disturbance.

“A horse,” demanded Conan. “The swiftest steed you have.”

“I open no gates at this time of night,” grumbled the horse trader.

Conan rattled his coins.

“Dog’s son knave! Don’t you see I’m white, and alone? Come down, before I smash your door!”

Presently, on a bay stallion, Conan was riding toward the house of Aram Baksh.

He turned off the road into the alley that lay between the tavern compound and the date-palm garden, but he did not pause at the gate. He rode on to the northeast corner of the wall, then turned and rode along the north wall to halt within a few paces of the northwest angle. No trees grew near the wall, but there were some low bushes. To one of these he tied his horse, and was about to climb into the saddle again, when he heard a low muttering of voices beyond the corner of the wall.

Drawing his foot from the stirrup he stole to the angle and peered around it. Three men were moving down the road toward the palm-groves, and from their slouching gait he knew they were negroes. They halted at his low call, bunching themselves together as he strode toward them, his sword in his hand. Their eyes gleamed whitely in the starlight. Their brutish lust shone in their ebony faces, but they knew their three cudgels could not prevail against his sword, just as he knew it.

“Where are you going?” he challenged.

“To bid our brothers put out the fire in the pit beyond the groves,” was the sullen, guttural reply. “Aram Baksh promised us a man, but he lied. We found one of our brothers dead in the trap-chamber. We go hungry this night.”

“I think not,” smiled Conan. “Aram Baksh will give you a man. Do you see that door?”

He pointed to a small, iron-bound portal set in the midst of the western wall.

“Wait there. Aram Baksh will give you a man.”

Backing warily away until he was out of reach of a sudden bludgeon blow, he turned and melted around the northwest angle of the wall. Reaching his horse he paused to ascertain that the blacks were not sneaking after him, and then he climbed into the saddle and stood upright on it, quieting the uneasy steed with a low word. He reached up, grasped the coping of the wall and drew himself up and over. There he studied the grounds for an instant. The tavern was built in the southwest corner of the enclosure, the remaining space of which was occupied by groves and gardens. He saw no one in the grounds. The tavern was dark and silent, and he knew all the doors and windows were barred and bolted.

Conan knew that Aram Baksh slept in a chamber that opened into a cypress-bordered path that led to the door in the western wall. Like a shadow he glided among the trees and a few moments later he rapped lightly on the chamber door.

“What is it?” asked a rumbling voice within.

“Aram Baksh!” hissed Conan. “The blacks are stealing over the wall!”

Almost instantly the door opened, framing the tavern-keeper, naked but for his shirt, with a dagger in his hand.

He craned his neck to stare into the Cimmerian’s face.

“What tale is this—you!”

Conan’s vengeful fingers strangled the yell in his throat. They went to the floor together and Conan wrenched the dagger from his enemy’s hand. The blade glinted in the starlight, and blood spurted. Aram Baksh made hideous noises, gasping and gagging on a mouthful of blood. Conan dragged him to his feet and again the dagger slashed, and most of the curly beard fell to the floor.

Still gripping his captive’s throat—for a man can scream incoherently even with his tongue slit—Conan dragged him out of the dark chamber and down the cypress-shadowed path, to the iron-bound door in the outer wall. With one hand he lifted the bolt and threw the door open, disclosing the three shadowy figures which waited like black vultures outside. Into their eager arms Conan thrust the inn-keeper.

A horrible, blood-choked scream rose from the Zamboulan’s throat, but there was no response from the silent tavern. The people there were used to screams outside the wall. Aram Baksh fought like a wild man, his distended eyes turned frantically on the Cimmerian’s face. He found no mercy there. Conan was thinking of the scores of wretches who owed their bloody doom to this man’s vile greed.

In glee the negroes dragged him down the road, mocking his frenzied gibberings. How could they recognize Aram Baksh in this half-naked, blood-stained figure, with the grotesquely shorn beard and unintelligible babblings? The sounds of the struggle came back to Conan, standing beside the gate, even after the clump of figures had vanished among the palms.

Closing the door behind him, Conan returned to his horse, mounted and turned westward, toward the open desert, swinging wide to skirt the sinister belt of palm-groves. As he rode he drew from his belt a ring in which gleamed a jewel that snared the starlight in a shimmering iridescence. He held it up to admire it, turning it this way and that. The compact bag of gold pieces clinked gently at his saddle bow, like a promise of the greater riches to come.

“I wonder what she’d say if she knew I recognized her as Nafertari and him as Jungir Khan the instant I saw them,” he mused. “I knew the Star of Khorala, too. There’ll be a fine scene if she ever guesses that I slipped it off his finger while I was tying him with his sword-belt. But they’ll never catch me with the start I’m getting.”

He glanced back at the shadowy palm groves, among which a red glare was mounting. A chanting rose to the night, vibrating with savage exultation. And another sound mingled with it, a mad, incoherent screaming, a frenzied gibbering in which no words could be distinguished. The noise followed Conan as he rode westward beneath the paling stars.

Conan, who had been living with a wandering tribe of Zuagirs, Shemitish nomads, wandered into Zamboula, a strange, hybrid city in the desert on the disputed border of Stygia and the Hyrkanian domains. Zamboula was inhabited by Stygians, Shemites, and many mixed breeds, and ruled over by the Hyrkanians. A satrap ruled there, one Jungir Khan, with Hyrkanian soldiers. The city contained and was adjacent too many oases with palm groves. Conan, intending to spend the night at the tavern of one Aram Baksh, was warned by a Shemite tribesman that other desert men and travellers had spent the night at Aram’s house, and never been seen again. He said that no bodies had ever been found on the place, but beyond the city’s outskirts—the city was not wall—there was a hollow with a pit in it where charred human bones had been found. The Shemite believed Aram was was a devil in disguise who had traffic with demons of the desert. Conan gave no heed to the warning, and went to Aram’s house, which was on the outskirts of the city. Aram gave him a room opening onto a street which ran directly into the desert between groves of palms. During the night Conan was awakened by the stealthy opening of the one door, and sprang up to cut down a huge black slave who had stolen into his room. He was a cannibal slave from Darfar, far to the south, and Conan realized that Aram was selling his guests to these beasts. Go into the street, intending to enter the tavern by another door and cut Aram down, he saw three blacks skulking along the street with a captive girl. He attacked them and cut them down, and hid with the girl while a large band of them stole past, headed for the cooking-pit beyond the outskirts. The girl told him she was a dancing girl in the temple of Hanuman, that she loved a young Hyrkanian soldier, and was desired by the priest of Hanuman, a Stygian, Totrasmek. She said the priest by his magic had driven the young soldier, and he had tried to slay her. Fleeing from him she had been seized by the black who skulked about the streets at night, seizing and devouring all they could. As she ceased to talk the mad soldier came upon them and Conan knocked him senseless and bound him. Then lifting him, he followed her to a place in the city where a negro slave—not a cannibal—took charge of the senseless soldier, whom she had first searched for a ring and a great jewel—the only thing he would not give her. She had given him the drug given her by the priest to make him sleep, to steal this jewel. But it had driven him mad. She persuaded Conan to help her kill the priest. They went to the temple of Hanuman and entering, she tried to open the secret door behind the idol, but a hand seized her hair and dragged her through. A monstrous dwarf dragged her before Totrasmek who made her dance naked between four cobras conjured out of smoke. Conan, trying to reach the hidden chamber by another route, killed a giant executioner, and leaning through curtains, slew Totrasmek. She search him after Conan had killed the dwarf, but did not find the jewel. Then she told Conan that she was a famous courtesan of the city, and the young soldier was in reality Jungir Khan, the satrap. They returned and found him dazed but sane, and she told Conan to return to the palace the next morning for his reward. He returned to the house of Aram and gave the tavern-keeper in the hands of the negroes, first slitting his tongue so he could not talk. Then he took to the desert, for he had known the girl and the soldier all along, and had himself stolen the jewel she sought.