Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

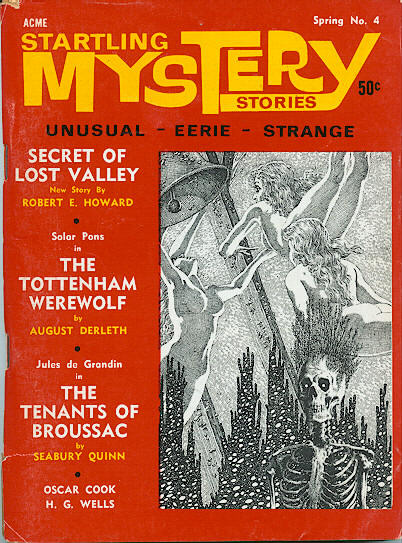

Published in Startling Mystery Stories, Vol. 1, No. 4 (#4; Spring 1967).

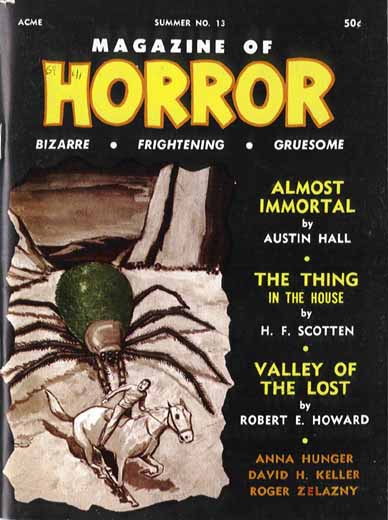

Note: this is not the same story as “Valley of the Lost” (aka “King of the Forgotten People”), first published in Magazine of Horror, #13 (Summer 1966); I don’t have that story yet, but might as well I’m dump that cover in here before I forget where I left it.

As a wolf spies upon its hunters, John Reynolds watched his pursuers. He lay close in a thicket on the slope, an inferno of hate seething in his heart. He had ridden hard; up the slope behind him, where the dim path wound up out of Lost Valley, his crank-eyed mustang stood, head drooping, trembling, after the long run. Below him, not more than eighty yards away, stood his enemies, fresh come from the slaughter of his kinsmen.

In the clearing fronting Ghost Cave they had dismounted and were arguing among themselves. John Reynolds knew them all with an old, bitter hate. The black shadow of feud lay between them and himself.

The feuds of early Texas have been neglected by chroniclers who have sung the feuds of the Kentucky mountains, though the men who first settled the Southwest were of the same breed as those mountaineers. But there was a difference; in the mountain country feuds dragged on for generations; on the Texas frontier they were short, fierce, and appallingly bloody.

The Reynolds-McCrill feud was long, as Texas feuds went: fifteen years had passed since old Esau Reynolds stabbed young Braxton McCrill to death with his bowie knife in the saloon at Antelope Wells, in a quarrel over range rights. For fifteen years the Reynoldses and their kin—the Brills, Allisons, and Donnellys—had been at open war with the McCrills and their kin—the Killihers, the Fletchers, and the Ords. There had been ambushes in the hills, murders on the open range, and gun-fights on the streets of the little cowtowns. Each clan had rustled the other’s cattle wholesale. Gunmen and outlaws called in by both sides to participate for pay, had spread a reign of terror and lawlessness throughout the vicinity. Settlers shunned the war-torn range; the feud became a red obstacle in the way of progress and development, a savage retrogression which was demoralizing the whole countryside.

Little John Reynolds cared. He had grown up in the atmosphere of the feud, and it had become a burning obsession with him. The war had taken fearful toll on both clans, but the Reynolds clan had suffered most. John was the last of the fighting Reynoldses, for Esau, the grim old patriarch who ruled the clan, would never again walk or sit in a saddle, with his legs paralyzed by McCrill bullets. John had seen his brothers shot down from ambush or killed in pitched battles.

Now the last stroke had nearly wiped out the waning clan. John Reynolds cursed as he thought of the trap into which they had walked in the saloon at Antelope Wells; the hidden foes had opened their murderous fire without warning. There had fallen his cousin, Bill Donnelly; his sister’s son, young Jonathon Brill; his brother-in-law, Job Allison; and Steve Kerney, the hired gunman. How he himself had shot his way through and gained the hitching rack, untouched by the blasting hail of lead, John Reynolds hardly knew. They had pressed him so closely he had not time to mount his long-limbed rangy bay, but had been forced to take the first horse he came to—the crank-eyed, speedy, but short-winded mustang of the dead Jonathon Brill.

He had distanced his pursuers for a while, had gained the uninhabited hills, and swung back into mysterious Lost Valley, with its silent thickets and crumbling stone columns, where he intended to double back over the hills and gain the country of the Reynolds. But the mustang had failed him. He had tied it up the slope, out of sight of the valley floor, and crept back—to see his enemies ride into the valley. There were five of them: old Jonas McCrill, with the perpetual snarl twisting his wolfish lips; Saul Fletcher, with his black beard and the limping, dragging gait that a fall in his youth from a wild mustang had left him; Bill Ord and Peter Ord, brothers; and the outlaw Jack Solomon.

JonasMcCrill’s voice came up to the silent watcher. “And I tell yuh he’s a-hidin’ somewhere in this valley. He was a-ridin’ that mustang and it didn’t never have no guts. I’m bettin’ it give plumb out on him time he got this far.”

“Well,” came the voice of Saul Fletcher, “what’re we a-standin’ ’round pow-wowin’ for? Why don’t we start huntin’ him?”

“Not so fast,” growled old Jonas. “Remember it’s John Reynolds we’re a-chasin’. We got plenty time.”

John Reynolds’ fingers hardened on the stock of his single-action .45. There were two cartridges unfired in the cylinder. He pushed the muzzle through the stems of the thicket in front of him, his thumb drawing back the wicked fanged hammer. His grey eyes narrowed and became opaque as ice as he sighted down the long blue barrel. An instant he weighed his hatred, and chose Saul Fletcher. All the hate in his soul centered for an instant on that brutal, black-bearded face, and the limping tread he had heard that night he lay wounded in a besieged corral, with his brother’s riddled corpse beside him, and fought off Saul and his brothers.

John Reynolds’ finger crooked and the crash of the shot broke the echoes of the sleeping hills. Saul Fletcher swayed, fliinging his black beard drunkenly upward, and crashed face-down and headlong. The others, with the quickness of men accustomed to frontier warfare, dropped behind rocks, and their answering shots roared back as they combed the slope blindly. The bullets tore through the thickets, whistling over the unseen killer’s head. High up on the slope the mustang, out of sight of the men in the valley but frightened by the noise, screamed shrilly, and, rearing, snapped the reins that held him and fled away up the hill path. The drum of his hoofs on the stones dwindled in the distance.

Silence reigned for an instant, then came Jonas McCrill’s wrathful voice: “I told yuh he was a-ridin’ here! Come outa there; he’s got clean away.”

The old fighter’s rangy frame rose up from behind the rock where he had taken refuge. Reynolds, grinning fiercely, took steady aim; then some instinct of self-preservation held his hand. The others came out into the open.

“What are we a-waitin’ on?” yelled young Bill Ord, tears of rage in his eyes. “Here that coyote’s done shot Saul and’s ridin’ hell-for-leather away from here, and we’re a-standin’ ’round jawin’. I’m a-goin’ to . . .” he started for his horse.

“Yuh’re a-goin’ to listen to me!” roared old Jonas. “I warned yuh to go slow, but yuh would come lickety-split along like a bunch of blind buzzards, and now Saul’s layin’ there dead. If we ain’t careful, John Reynolds’ll kill all of us. Didn’t I tell yuh-all he was here? Likely stopped to rest his horse. He can’t go far. This here’s a long hunt, like I told yuh at first. Let him get a good start. Long as he’s ahead of us, we got to watch for ambushes. He’ll try to get back onto the Reynolds range. Well, we’re a-goin’ after him slow and easy and keep him hazed back all the time. We’ll be a-ridin’ the inside of a big half-circle and he can’t get by us—not on that shortwinded mustang. We’ll just foller him and gather him in when his horse can’t do no more. And I purty well know where he’ll come to bay at—Blind Horse Canyon.”

“We’ll have to starve him out, then,” growled Jack Solomon.

“No, we won’t,” grinned old Jonas. “Bill, you hightail it back to Antelope and git five or six sticks of dynamite. Then you git a fresh horse and follow our trail. If we catch him before he gits to the canyon, all right. If he beats us there and holds up, we’ll wait for yuh, and then blast him out.”

“What about Saul?” growled Peter Ord.

“He’s dead,” grunted Jonas. “Nothin’ we can do for him now. No time to take him back.” He glanced up at the sky, where already black dots wheeled against the blue. His gaze drifted to the walled-up mouth of the cavern in the steep cliff which rose at right angles to the slope up which the path wandered.

“We’ll break open the cave and put him in it,” he said. “We’ll pile up the rocks again and the wolves and buzzards can’t git to him. Maybe several days before we git back.”

“That cave’s ha’nted,” muttered Bill Ord, uneasily. “The Injuns said if yuh put a dead man in there, he’d come walkin’ out at midnight.”

“Shet up and help pick up pore Saul,” snapped Jonas. “Here’s your own kin a-layin’ dead, and his murderer a-ridin’ further away every second, and you talk about ha’nts.”

As they lifted the corpse, Jonas drew the long-barreled six-shooter from the holster and shoved the weapon into his own waistband.

“Pore Saul,” he grunted. “He’s shore dead. Shot plumb through the heart. Dead before he hit the ground, I reckon. Well, we’ll make that damned Reynolds pay for it.”

They carried the dead man to the cave, and, laying him down, attacked the rocks which blocked the entrance. These were soon torn aside, and Reynolds saw the men carry the body inside. They emerged almost immediately, minus their burden, and mounted their horses. Young Bill Ord swung away down the valley and vanished among the trees; the rest cantered along the winding trail that led up into the hills. They passed within a hundred feet of his refuge and John Reynolds hugged the earth, fearing discovery. But they did not glance in his direction. He heard the dwindling of their hoofs over the rocky path; then silence settled again over the ancient valley.

John Reynolds rose cautiously, looked about him as a hunted wolf looks, then made his way quickly down the slope. He had a very definite purpose in mind. A single unfired cartridge was all his ammunition; but about the dead body of Saul Fletcher was a belt well filled with .45 caliber cartridges.

As he attacked the rocks heaped in the cave’s mouth, there hovered in his mind the curious dim speculations which the cave and the valley itself roused in him. Why had the Indians named it the Valley of the Lost—which white men shortened to Lost Valley? Why had the red men shunned it? Once in the memory of white men, a band of Kiowas, fleeing the vengeance of Bigfoot Wallace and his rangers, had taken up their abode there and fallen on evil times. The survivors of the tribe had fled, telling wild tales in which murder, fratricide, insanity, vampirism, slaughter, and cannibalism had played grim parts. Then six white men, brothers—Stark by name—had settled in Lost Valley. They had re-opened the cave which the Kiowas had blocked up. Horror had fallen on them and in one night five died by one another’s hands. The survivor had walled up the cave mouth again and departed, where none knew. Word had drifted through the settlements of a man named Stark who had come among the remnants of those Kiowas who had once lived in Lost Valley, and, after a long talk with them, had cut his own throat with his bowie knife.

What was the mystery of Lost Valley, if not a web of lies and legends? What the meaning of those crumbling stones, which, scattered all over the valley, half hidden in the climbing growth, bore a curious symmetry, especially in the moonlight, so that some people believed when the Indians swore they were the half destroyed columns of a prehistoric city which once stood in Lost Valley? Before it crumbled into a heap of grey dust, Reynolds himself had seen a skull unearthed at the base of a cliff by a wandering prospector. It seemed neither Caucasian nor Indian—a curious, peaked skull, which but for the formation of the jaw bones might have been that of some unknown antediluvian animal.

Such thoughts flitted vaguely and momentarily through John Reynolds’ mind as he dislodged the boulders, which the McCrills had put back loosely—just firmly enough to keep a wolf or buzzard from squeezing through. In the main his thoughts were engrossed with the cartridges in dead Saul Fletcher’s belt. A fighting chance! A lease on life! He would fight his way out of the hills yet; would bring in more gunmen and cut-throats for striking back. He would flood the whole range with blood, and bring the countryside to ruin, if by those means he might be avenged. For years he had been the moving factor in the feud. When even old Esau had weakened and wished for peace, John Reynolds had kept the flame of hate blazing. The feud had become his own driving motive, his one interest in life and reason for existence. The last boulders fell aside.

John Reynolds stepped into the semi-gloom of the cavern. It was not large, but the shadows seemed to cluster there in almost tangible substance. Slowly his eyes accustomed themselves, and an involuntary exclamation broke from his lips—the cave was empty! He swore in bewilderment. He had seen men carry Saul Fletcher’s corpse into the cave and come out again, empty handed. Yet no corpse lay on the dusty cavern floor. He went to the back of the cave, glanced at the straight, even wall, bent and examined the smooth rock floor. His keen eyes, straining in the gloom, made out a dull smear of blood on the stone. It ended abruptly at the back wall, and there was no stain on the wall.

Reynolds leaned closer, supporting himself by a hand propped against the stone wall. And suddenly, shockingly, the sensation of solidity and stability vanished. The wall gave way beneath his propping hand; a section swung inward, precipitating him headlong through a black gaping opening. His cat-like quickness could not save him. It was as if the yawning shadows reached tenuous and invisible hands to jerk him headlong into the darkness.

He did not fall far. His out-flung hands struck what seemed to be steps carved in the stone, and on them he scrambled and floundered for an instant. Then he righted himself and turned back to the opening through which he had fallen. But the secret door had closed, and only a smooth stone wall met his groping fingers. He fought down a rising panic. How the McCrills had come to know of this secret chamber he could not say, but quite evidently they had placed Saul Fletcher’s body in it. And there, trapped like a rat, they would find John Reynolds when they returned. Then a grim smile curled Reynolds’ thin lips. When they opened the secret door, he would be hidden in the darkness, while they would be etched against the dim light of the outer cave. Where could he find a more perfect ambush? But first he must find the body and secure the cartridges.

He turned to grope his way down the steps and his first stride brought him to a level floor. It was a sort of narrow tunnel, he decided, for though he could not touch the roof, a stride to the right or the left and his outstretched hand encountered a wall, seemingly too even and symmetrical to have been the work of nature. He went slowly, groping in the darkness, keeping in touch with the walls and momentarily expecting to stumble on Saul Fletcher’s body. And as he did not, a dim horror began to grow in his soul. The McCrills had not been in the cavern long enough to carry the body so far back into the darkness. A feeling was rising in John Reynolds that the McCrills had not entered the tunnel at all—that they were not aware of its existence. Then where in the name of sanity was Saul Fletcher’s corpse?

He stopped short, jerking out his six-shooter. Something was coming up the dark tunnel—something that walked upright and lumberingly. John Reynolds knew it was a man, wearing high-heeled riding boots; no other footwear makes the same stilted sound. He caught the jingle of the spurs. And a dark tide of nameless horror moved sluggishly in John Reynolds’ mind as he heard that halting tread approach, and remembered the night when he had lain at bay in the old corral, with the younger brother dying beside him, and heard a limping, dragging footstep, out in the night where Saul Fletcher led his wolves and sought for a way to come upon his back.

Had the man only been wounded? These steps sounded stiff and blundering, such as a wounded man might make. No—John Reynolds had seen too many men die; he knew that his bullet had gone straight through Saul Fletcher’s heart, possibly tearing the heart out, certainly killing him instantly. Besides, he had heard old Jonas McCrill declare the man was dead. No—Saul Fletcher lay lifeless somewhere in this black cavern. It was some other lame man who was coming up that silent tunnel.

Now the tread ceased. The man was fronting him, separated only by a few feet of utter blackness. What was there in that to quicken the iron pulse of John Reynolds, who had unflinchingly faced death times without number?—what to make his flesh crawl and his tongue freeze to his palate?—to awake sleeping instincts of fear as a man senses the presence of an unseen serpent, and make him feel that somehow the other was aware of his presence with eyes that pierced the darkness?

In the silence John Reynolds heard the staccato pounding of his own heart. And with shocking suddenness the man lunged. Reynolds’ straining ears caught the first movement of that lunge and he fired pointblank. And he screamed—a terrible animal-like scream. Heavy arms locked upon him and unseen teeth worried at his flesh; but in the frothing frenzy of his fear, his own strength was superhuman. For in the flash of the shot he had seen a bearded face with a slack hanging mouth and staring dead eyes. Saul Fletcher! The dead, come back from hell.

As in a nightmare, Reynolds entered a fiendish battle in the dark where the dead sought to drag down the living. He was flung with bone-shattering force against the stone walls. Dashed to the floor, the silent horror squatted ghoul-like upon him, its horrid fingers sinking deep into his throat.

In that nightmare, John Reynolds had no time to doubt his own sanity. He knew that he was battling a dead man. The flesh of his foe was cold with a charnel house clamminess. Under the torn shirt he had felt the round bullet-hole, caked with clotted blood. No single sound came from the loose lips.

Choking and gasping, John Reynolds tore the strangling hands aside and flung the thing off. For an instant the darkness again separated them; then the horror came hurtling toward him again. As the thing lunged, Reynolds caught blindly and gained the wrestling hold he wished; and hurling all his power behind the attack, he dashed the horror headlong, falling upon it with his full weight. Saul Fletcher’s spine snapped like a rotten branch and the tearing hands went limp, the straining limbs relaxed. Something flowed from the lax body and whispered away through the darkness like a ghostly wind, and John Reynolds instinctively knew that at last Saul Fletcher was truly dead.

Panting and shaken, Reynolds rose. The tunnel remained in utter darkness. But down it, in the direction from which the walking corpse had come stalking, there whispered a faint throbbing that was hardly sound at all, yet had in its pulsing a dark weird music. Reynolds shuddered and the sweat froze on his body. The dead man lay at his feet in the thick darkness, and faintly to his ears came that unbearably sweet, unbearably evil echo, like devil-drums beating faint and far in the dim caverns of hell.

Reason urged him to turn back—to fight against that blind door until he burst its stone, if human power could burst it; but he realized that reason and sanity had been left behind him. A single step had plunged him from a normal world of material realities into a realm of nightmare and lunacy. He decided that he was mad, or else dead and in hell. Those dim tom-toms drew him; they tugged at his heart-strings eerily. They repelled him and filled his soul with shadowy and monstrous conjectures, yet their call was irresistible. He fought the mad impulse to shriek and fling his arms wildly aloft, and run down the black tunnel as a rabbit runs down the prairie dog’s burrow into the jaws of the waiting rattler.

Fumbling in the dark, he found his revolver, and still fumbling he loaded it with cartridges from Saul Fletcher’s belt. He felt no more aversion now, at touching the body, than he would have felt at handling any dead flesh. Whatever unholy power had animated the corpse, it had left it when the snapping of the spine had unraveled the nerve centers and disrupted the roots of the muscular system.

Then, revolver in hand, John Reynolds went down the tunnel, drawn by a power he could not fathom, toward a doom he could not guess.

The throb of the tom-toms grew only slightly in volume as he advanced. How far below the hills he was, he could not know, but the tunnel slanted downward and he had gone a long way. Often his groping hands encountered doorways—corridors leading off the main tunnel, he believed. At last he was aware that he had left the tunnel and had come out into a vast open space. He could see nothing, but he somehow felt the vastness of the place. And in the darkness a faint light began. It throbbed as the drums throbbed, waning and waxing in time to their pulsing, but it grew slowly, casting a weird glow that was more like green than any color Reynolds had ever seen—but was not really green, nor any other sane or earthly color.

Reynolds approached it. It widened. It cast a shimmering radiance over the smooth stone floor, illuminating fantastic mosaics. It cast its sheen high in the hovering shadows, but he could see no roof. Now he stood bathed in its weird glow, so that his flesh looked like a dead man’s. Now he saw the roof, high and vaulted, brooding far above him like a dusky midnight sky, and towering walls, gleaming and dark, sweeping up to tremendous heights, their bases fringed with squat shadows from which glittered other lights, small and scintillant.

He saw the source of the illumination, a strange carven stone altar on which burned what appeared to be a giant jewel of an unearthly hue, like the light it emitted. Greenish flame jetted from it; it burned as a bit of coal might burn, but it was not consumed. Just behind it a feathered serpent reared from its coils, a fantasy carven of some clear crystalline substance, the tints of which in the weird light were never the same, but which pulsed and shimmered and changed as the drums—now on all sides of him—pulsed and throbbed.

Abruptly something alive moved beside the altar and John Reynolds, though he was expecting anything, recoiled. At first he thought it was a huge reptile which slithered about the altar, then he saw that it stood upright as a man stands. As he met the menacing glitter of its eyes, he fired pointblank and the thing went down like a slaughtered ox, its skull shattered. Reynolds wheeled as a sinister rustling rose on his ears—at least these beings could be killed—then checked the lifted muzzle. The fringing shadows had moved out from the darkness at the base of the walls, and drawn about him a wide ring. And though at first glance they possessed the semblance of men, he knew they were not human.

The weird light flickered and danced over them, and back in the deeper darkness the soft, evil drums whispered their accompanying undertone everlastingly. John Reynolds stood aghast at what he saw.

It was not their dwarfish figures which caused his shudder, nor even the unnaturally made hands and feet—it was their heads. He knew now, of what race was the skull found by the prospector. Like it, these heads were peaked and malformed, curiously flattened at the sides. There was no sign of ears, as if their organs of hearing, like a serpent’s, were beneath the skin. The noses were like a python’s snout, the mouth and jaws much less human in appearance than his recollection of the skull would have led him to suppose. The eyes were small, glittering, and reptilian. The squamous lips writhed back, showing pointed fangs, and John Reynolds felt that their bite would be as deadly as a rattlesnake’s. Garments they wore none, nor did they bear any weapons.

He tensed himself for the death struggle, but no rush came. The snake-people sat down cross-legged about him in a great circle, and beyond the circle he saw them massed thick. And now he felt a stirring in his consciousness, an almost tangible beating of wills upon his senses. He was distinctly aware of a concentrated invasion of his innermost mind, and realized that these fantastic beings were seeking to convey their commands or wishes to him by medium of thought. On what common plane could he meet these inhuman creatures? Yet in some dim, strange, telepathic way they made him understand some of their meaning; and he realized with a grisly shock that, whatever these things were now, they had once been at least partly human, else they had never been able to so bridge the gulf between the completely human and the completely bestial.

He understood that he was the first living man to come into their innermost realm, the first to look on the shining serpent, the Terrible Nameless One who was older than the world; that before he died, he was to know all which had been denied to the sons of men concerning the mysterious valley, that he might take this knowledge into Eternity with him, and discuss these matters with those who had gone before him.

The drums rustled, the strange light leaped and shimmered, and before the altar came one who seemed in authority—an ancient monstrosity whose skin was like the whitish hide of an old serpent, and who wore on his peaked skull a golden circlet, set with weird gems. He bent and made suppliance to the feathered snake. Then with a sharp implement of some sort which left a phosphorescent mark, he drew a cryptic triangular figure on the floor before the altar, and in the figure he strewed some sort of glimmering dust. From it reared up a thin spiral which grew to a gigantic shadowy serpent, feathered and horrific, and then changed and faded and became a cloud of greenish smoke. This smoke billowed out before John Reynolds’ eyes and hid the serpent-eyed ring, and the altar, and the cavern itself. All the universe dissolved into the green smoke, in which titanic scenes and alien landscapes rose and shifted and faded, and monstrous shapes lumbered and leered.

Abruptly the chaos crystallized. He was looking into a valley which he did not recognize. Somehow he knew it was Lost Valley, but in it towered a gigantic city of dully gleaming stone. John Reynolds was a man of the outlands and the waste places. He had never seen the great cities of the world; but he knew that nowhere in the world today such a city reared up to the sky.

Its towers and battlements were those of an alien age. Its outline baffled his gaze with its unnatural aspects; it was a city of lunacy to the normal human eye, with its hints of alien dimensions and abnormal principles of architecture. Through it moved strange figures—human, yet of a humanity definitely different from his own. They were clad in robes; their hands and feet were less abnormal, their ears and mouths more like those of normal humans; yet there was an undoubted kinship between them and the monsters of the cave. It showed in the curious peaked skull, though this was less pronounced and bestial in the people of the city.

He saw them in the twisting streets, and in their colossal buildings, and he shuddered at the inhumanness of their lives. Much they did was beyond his ken; he could understand their actions and motives no more than a Zulu savage might understand the events of modern London. But he did understand that these people were very ancient and very evil. He saw them enact rituals that froze his blood with horror, obscenities and blasphemies beyond his understanding. He grew sick with a sensation of contamination. Somehow he knew that this city was the remnant of an outworn age—that this people represented the survival of an epoch lost and forgotten.

Then a new people came upon the scene. Over the hills came wild men clad in hides and feathers, armed with bows and flint-tipped weapons. They were, Reynolds knew, Indians—and yet not Indians as he knew them. They were slant-eyed, and their skins were yellowish rather than copper-colored. Somehow he knew that these were the nomadic ancestors of the Toltecs, wandering and conquering on their long trek before they settled in upland valleys far to the south and evolved their own special type and civilization. These were still close to the primal Mongolian rootstock, and he gasped at the gigantic vistas of time this realization evoked.

Reynolds saw the warriors move like a giant wave on the towering walls. He saw the defenders man the towers and deal death in strange and grisly forms to them. He saw the invaders reel back again and again, then come on once more with the blind ferocity of the primitive. This strange evil city, filled with mysterious people of a different order, was in their path, and they could not pass until they had stamped it out.

Reynolds marveled at the fury of the invaders, who wasted their lives like water, matching the cruel and terrible science of an unknown civilization with sheer courage and the might of manpower. Their bodies littered the plateau, but not all the forces of hell could keep them back. They rolled like a wave to the foot of the towers. They scaled the walls in the teeth of sword and arrow and death in ghastly forms; they gained the parapets; they met their enemies hand-to-hand. Bludgeons and axes beat down the lunging spears, the thrusting swords. The tall figures of the barbarians towered over the smaller forms of the defenders.

Red hell raged in the city. The siege became a street battle, the battle a rout, the rout a slaughter. Smoke rose and hung in clouds over the doomed city.

The scene changed. Reynolds looked on charred and ruined walls from which smoke still rose. The conquerors had passed on; the survivors gathered in the red-stained temple before their curious god, a crystalline serpent on a fantastic stone altar. Their age had ended; their world crumbled suddenly. They were the remnants of an otherwise extinct race. They could not rebuild their marvelous city and they feared to remain within its broken walls, a prey to every passing tribe. Reynolds saw them take up their altar and its god and follow an ancient man clad in a mantle of feathers and wearing on his head a gem-set circlet of gold. He led them across the valley to a hidden cave. They entered and squeezing through a narrow rift in the back wall, came into a vast network of caverns honeycombing the hills. Reynolds saw them at work, exploring these labyrinths, excavating and enlarging, hewing the walls and floors smooth, enlarging the rift that let into the outer cavern and setting therein a cunningly hung door, so that it seemed part of the solid wall.

Then an ever-shifting panorama denoted the passing of many centuries. The people lived in the caverns, and as time passed they adapted themselves more and more to their surroundings, each generation going less frequently into the outer sunlight. They learned to obtain their food in shuddersome ways from the earth. Their ears grew smaller, their bodies more dwarfish, their eyes more catlike. John Reynolds stood aghast as he watched the race changing through the ages.

Outside in the valley the deserted city crumbled and fell into ruins, becoming prey to lichen and weed and tree. Men came and briefly meditated among these ruins—tall Mongolian warriors, and dark inscrutable little people men call the Mound Builders. And as the centuries passed, the visitors conformed more and more to the type of Indian as he knew it, until at last the only men who came were painted red men with stealthy feet and feathered scalp-locks. None ever tarried long in that haunted place with its cryptic ruins.

Meanwhile, in the caverns, the Old People abode and grew strange and terrible. They fell lower and lower in the scale of humanity, forgetting first their written language, and gradually their human speech. But in other ways they extended the boundaries of life. In their nighted kingdom they discovered other, older caverns, which led them into the very bowels of the earth. They learned lost secrets, long-forgotten or never known by men, sleeping in the blackness far below the hills. Darkness is conducive to silence, so they gradually lost the power of speech, a sort of telepathy taking its place. And with each grisly gain they lost more of their human attributes: Their ears vanished; their noses grew snoutlike; their eyes became unable to bear the light of the sun, and even the stars. They had long abandoned the use of fire, and the only light they used was the weird gleams evoked from their gigantic jewel on the altar, and even this they did not need. They changed in other ways. John Reynolds, watching, felt the cold sweat bead his body. For the slow transmutation of the Old People was horrible to behold, and many and hideous were the shapes which moved among them before their ultimate mold and nature were evolved.

Yet they remembered the sorcery of their ancestors and added to this their own black wizardry developed far below the hills. And at last they attained the peak of that necromancy. John Reynolds had had horrific inklings of it in fragmentary glimpses of the olden times, when the wizards of the Old People had sent forth their spirits from their sleeping bodies to whisper evil things in the ears of their enemies.

A tribe of tall painted warriors came into the valley, bearing the body of a great chief, slain in tribal warfare.

Long eons had passed. Of the ancient city only scattered columns stood among the trees. A landslide had laid bare the entrance of the outer cavern. This the Indians found and therein they placed the body of their chief with his weapons broken beside him. Then they blocked up the cave mouth with stones, and took up their journey, but night caught them in the valley.

Through all the ages, the Old People had found no other entrance or exit to or from the pits, save the small outer cave; it was the one doorway between their grim realm and the world they had so long abandoned. Now they came through the secret door into the outer cavern, whose dim light they could endure, and John Reynolds’ hair stood up at what he saw. For they took the corpse and laid it before the altar of the feathered serpent, and an ancient wizard lay upon it, his mouth against the mouth of the dead. Above them tom-toms pulsed and strange fires flickered, and the voiceless votaries with soundless chants invoked gods forgotten before the birth of Egypt, until unhuman voices bellowed in the outer darkness and the sweep of monstrous wings filled the shadows. And slowly life ebbed from the sorcerer and stirred the limbs of the dead chief. The body of the wizard rolled limply aside and the corpse of the chief stood up stiffly; and with puppetlike steps and glassy staring eyes it went up the dark tunnel and through the secret door into the outer cave. Its dead hands tore aside the stones, and into the starlight stalked the Horror.

Reynolds saw it walk stiffly under the shuddering trees while the night things fled gibbering. He saw it come into the camp of the warriors. The rest was horror and madness, as the dead thing pursued its former companions and tore them limb from limb. The valley became a shambles before one of the braves, conquering his terror, turned on his pursuer and hewed through its spine with a stone ax.

And even as the twice-slain corpse crumpled, Reynolds saw, on the floor of the cavern before the carven serpent, the form of the wizard quicken and live as his spirit returned to him from the corpse he had caused it to animate.

The soundless glee of incarnate demons shook the crawling blackness of the pits, and Reynolds shrank before the verminous fiends gloating over their newfound power to deal horror and death to the sons of men, their ancient enemies.

But the word spread from clan to clan, and men came not to the Valley of the Lost. For many a century it lay dreaming and deserted beneath the sky. Then came mounted braves with trailing war-bonnets, painted with the colors of the Kiowas, warriors of the north who knew nothing of the mysterious valley. They pitched their camps in the very shadows of those sinister monoliths which were now no more than shapeless stones.

They placed their dead in the cavern. And Reynolds saw the horrors that took place when the dead came ravening by night among the living to slay and devour—and to drag screaming victims into the nighted caverns and the demoniac doom that awaited them. The legions of hell were loosed in the Valley of the Lost, where chaos reigned and nightmare and madness stalked. Those who were left alive and sane walled up the cavern and rode out of the hills like men riding from hell.

Once more Lost Valley lay gaunt and naked to the stars. Then again the coming of men broke the primal solitude, and smoke rose among the trees. And John Reynolds caught his breath with a start of horror as he saw these were white men, clad in the buckskins of an earlier day—six of them, so much alike that he knew they were brothers.

He saw them fell trees and build a cabin in the clearing. He saw them hunt game in the mountains and begin clearing a field for corn. And all the time he saw the vermin of the hills waiting with ghoulish lust in the darkness. They could not look from their caverns with their nighted eyes, but by their godless sorcery they were aware of all that took place in the valley. They could not come forth in their own bodies in the light, but they waited with the patience of night and the still places.

Reynolds saw one of the brothers find the cavern and open it. He entered and the secret door hung open. The man went into the tunnel. He could not see, in the darkness, the shapes of horror that stole slavering about him, but in sudden panic he lifted his muzzleloading rifle and fired blindly, screaming as the flash showed him the hellish forms that ringed him in. In the utter blackness following the vain shot they rushed, overthrowing him by the power of their numbers, sinking their snaky fangs into his flesh. As he died, he slashed half a dozen of them to pieces with his bowie knife, but the poison did its work quickly.

Reynolds saw them drag the corpse before the altar; he saw again the horrible transmutation of the dead, which rose grinning vacantly and stalked forth. The sun had set in a welter of dull crimson. Night had fallen. To the cabin where his brothers slept, wrapped in their blankets, stalked the dead. Silently the groping hands swung open the door. The Horror crouched in the gloom, its bared teeth shining, its dead eyes gleaming glassily in the starlight. One of the brothers stirred and mumbled, then sat up and stared at the motionless shape in the doorway. He called the dead man’s name—then he shrieked hideously—the Horror sprang. . . .

From John Reynolds’ throat burst a cry of intolerable horror. Abruptly he pictures vanished, with the smoke. He stood in the weird glow before the altar, the tom-toms throbbing softly and evilly, the fiendish faces hemming him in. And now from among them crept, on his belly like the serpent he was, the one which wore the gemmed circlet, venom dripping from his bared fangs. Loathsomely he slithered toward John Reynolds, who fought the temptation to leap upon the foul thing and stamp out its life. There was no escape; he could send his bullets crashing through the swarm and mow down all in front of the muzzle, but those would be as nothing beside the hundreds which hemmed him in. He would die there in the waning light, and they would send his corpse blundering forth, lent a travesty of life by the spirit of the wizard, just as they had sent Saul Fletcher. John Reynolds grew tense as steel as his wolf-like instinct to live rose above the maze of horror into which he had fallen.

And suddenly his human mind rose above the vermin who threatened him, as he was electrified by a swift thought that was like an inspiration. With a fierce inarticulate cry of triumph, he bounded sideways just as the crawling monstrosity lunged. It missed him, sprawling headlong, and Reynolds snatched from the altar the carven serpent, and holding it on high, thrust against it the muzzle of his cocked pistol. He did not need to speak. In the dying light his eyes blazed madly. The Old People wavered back. Before them lay he whose peaked skull Reynolds’ pistol had shattered. They knew a crook of his trigger finger would splinter their fantastic god into shining bits.

For a tense space the tableau held. Then Reynolds felt their silent surrender. Freedom in exchange for their god. It was again borne on him that these beings were not truly bestial, since true beasts know no gods. And this knowledge was the more terrible, for it meant that these creatures had evolved into a type neither bestial nor human, a type outside of nature and sanity.

The snakish figures gave back on each side, and the waning light sprang up again. As he went up the tunnel they were close at his heels, and in the dancing uncertain glow he could not be sure whether they walked as a man walks or crawled as a snake crawls. He had a vague impression that their gait was hideously compounded of both. He swerved far aside to avoid the sprawling bulk that had been Saul Fletcher, and so, with his gun muzzle pressed hard against the shining brittle image borne in his left hand, he came to the short flight of steps which led up to the secret door. There they came to a standstill. He turned to face them. They ringed him in a close half-circle, and he understood that they feared to open the secret door lest he dash, with their image, through the cavern into the sunlight, where they could not follow. Nor would he set down the god until the door was opened.

At last they withdrew several yards, and he cautiously set the image on the floor at his feet where he could snatch it up in an instant. How they opened the door he never knew, but it swung wide, and he backed slowly up the steps, his gun trained on the glittering god. He had almost reached the door—one backthrown hand gripped the edge—when the light went out suddenly and the rush came. A volcanic burst of effort shot him backward through the door, which was already rushing shut. As he leaped he emptied his gun full into the fiendish faces that suddenly filled the dark opening. They dissolved in red ruin, and as he raced madly from the outer cavern he heard the soft closing of the secret door, shutting that realm of horror from the human world.

In the glow of the westering sun, John Reynolds staggered drunkenly, clutching at stones and trees as a madman clutches at realities. The keen tenseness that had held him when he fought for his life fell from him and left him a quivering shell of disrupted nerves. An insane titter broke through his lips, and he rocked to and fro in ghastly laughter he could not check.

Then the clink of hoofs on stone sent him leaping behind a cluster of boulders. It was some hidden instinct which led him to take refuge; his conscious mind was too dazed and chaotic for thought or action.

Into the clearing rode Jonas McCrill and his followers—and a sob tore through Reynolds’ throat. At first he did not recognize them—did not realize that he had ever seen them before. The feud, with all other sane and normal things, lay lost and forgotten far back in dim vistas beyond the black tunnels of madness.

Two figures rode from the other side of the clearing—Bill Ord and one of the outlaw followers of the McCrills. Strapped to Ord’s saddle were several sticks of dynamite, done into a compact package.

“Well, gee whiz,” hailed young Ord, “I shore didn’t expect to meet yuh-all here. Did yuh git him?”

“Naw,” snapped old Jonas,” he’s done fooled us again. We came up with his horse, but he wasn’t on it. The rein was snapped like he’d had it tied and it’d broke away. I dunno where he is, but we’ll git him. I’m a-goin’ on to Antelope to git some more of the boys. Yuh-all git Saul’s body outa that cave and foller me as fast as yuh can.”

He reined away and vanished through the trees, and Reynolds, his heart in his mouth, saw the other four approach the cavern.

“Well, by God!” exclaimed Jack Solomon fiercely, “somebody’s done been here! Look! Them rocks are torn down!”

John Reynolds watched as one paralyzed. If he sprang up and called to them they would shoot him down before he could voice his warning. Yet it was not that which held him as in a vise; it was sheer horror which robbed him of thought and action, and froze his tongue to the roof of his mouth. His lips parted but no sound came forth. As in a nightmare he saw his enemies disappear into the cavern. Their voices, muffled, came back to him.

“By golly, Saul’s gone!”

“Look here, boys, here’s a door in the back wall!”

“By thunder, it’s open!”

“Let’s take a look!”

Suddenly from within the bowels of the hills crashed a fusillade of shots—a burst of hideous screams. Then silence closed like a clammy fog over the Valley of the Lost.

John Reynolds, finding voice at last, cried out as a wounded beast cries, and beat his temples with his clenched fists. He brandished them to the heavens, shrieking wordless blasphemies.

Then he ran staggeringly to Bill Ord’s horse which grazed tranquilly with the others beneath the trees. With clammy hands he tore away the package of dynamite, and without separating the sticks he punched a hole in the end of the middle stick with a twig. Then he cut a short—a very short—piece of fuse, and slipped a cap over one end which he inserted into the hole in the dynamite. In a pocket of the rolled up slicker bound behind the saddle he found a match, and lighting the fuse he hurled the bundle into the cavern. Hardly had it struck the back wall when with an earthquake roar it exploded.

The concussion nearly hurled him off his feet. The whole mountain rocked, and with a thunderous crash the cave roof fell. Tons and tons of shattered rock crashed down to obliterate all marks of Ghost Cave, and to shut the door to the pits forever.

John Reynolds walked slowly away; and suddenly the whole horror swept upon him. The earth seemed hideously alive under his feet, the sun foul and blasphemous over his head. The light was sickly, yellowish and evil, and all things were polluted by the unholy knowledge locked in his skull, like hidden drums beating ceaselessly in the blackness beneath the hills.

He had closed one Door forever, but what other nightmare shapes might lurk in hidden places and the dark pits of the earth, gloating over the souls of men? His knowledge was a reeking blasphemy which would never let him rest; forever in his soul would whisper the drums that throbbed in those dark pits where lurked demons that had once been men. He had looked on ultimate foulness, and his knowledge was a taint which would never let him stand clean before men again, or touch the flesh of any living thing without a shudder. If man, molded of divinity, could sink to such verminous obscenities, who could contemplate his eventual destiny unshaken?

And if such beings as the Old People existed, what other horrors might not lurk beneath the visible surface of the universe? He was suddenly aware that he had glimpsed the grinning skull beneath the mask of life, and that that glimpse made life intolerable. All certainty and stability had been swept away, leaving a mad welter of lunacy, nightmare, and stalking horror.

John Reynolds drew his gun and his horny thumb drew back the heavy hammer. Thrusting the muzzle against his temple, he pulled the trigger. The shot crashed echoing through the hills, and the last of the fighting Reynoldses pitched headlong.

Old Jonas McCrill, galloping back at the sound of the blast, found him where he lay, and wondered that his face should be that of an old, old man, his hair white as hoar-frost.