Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

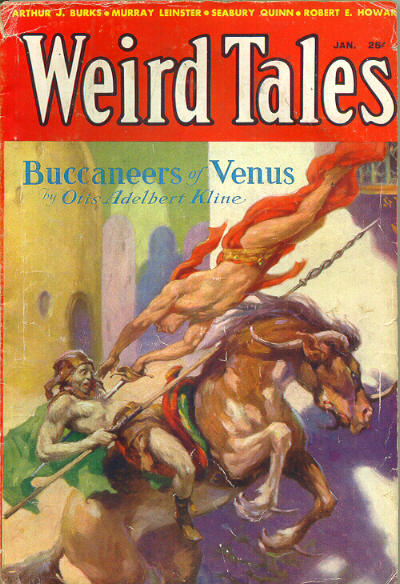

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 21, No. 1 (January 1933).

| I | II | III | IV | V |

They trapped the Lion on Shamu’s plain;

They weighted his limbs with an iron chain;

They cried aloud in the trumpet-blast,

They cried, “The Lion is caged at last!”

Woe to the cities of river and plain

If ever the Lion stalks again!

—Old Ballad.

The roar of battle had died away; the shout of victory mingled with the cries of the dying. Like gay-hued leaves after an autumn storm, the fallen littered the plain; the sinking sun shimmered on burnished helmets, gilt-worked mail, silver breastplates, broken swords and the heavy regal folds of silken standards, overthrown in pools of curdling crimson. In silent heaps lay war-horses and their steel-clad riders, flowing manes and blowing plumes stained alike in the red tide. About them and among them, like the drift of a storm, were strewn slashed and trampled bodies in steel caps and leather jerkins—archers and pikemen.

The oliphants sounded a fanfare of triumph all over the plain, and the hoofs of the victors crunched in the breasts of the vanquished as all the straggling, shining lines converged inward like the spokes of a glittering wheel, to the spot where the last survivor still waged unequal strife.

That day Conan, king of Aquilonia, had seen the pick of his chivalry cut to pieces, smashed and hammered to bits, and swept into eternity. With five thousand knights he had crossed the south-eastern border of Aquilonia and ridden into the grassy meadowlands of Ophir, to find his former ally, King Amalrus of Ophir, drawn up against him with the hosts of Strabonus, king of Koth. Too late he had seen the trap. All that a man might do he had done with his five thousand cavalrymen against the thirty thousand knights, archers and spearmen of the conspirators.

Without bowmen or infantry, he had hurled his armored horsemen against the oncoming host, had seen the knights of his foes in their shining mail go down before his lances, had torn the opposing center to bits, driving the riven ranks headlong before him, only to find himself caught in a vise as the untouched wings closed in. Strabonus’ Shemitish bowmen had wrought havoc among his knights, feathering them with shafts that found every crevice in their armor, shooting down the horses, the Kothian pikemen rushing in to spear the fallen riders. The mailed lancers of the routed center had re-formed, reinforced by the riders from the wings, and had charged again and again, sweeping the field by sheer weight of numbers.

The Aquilonians had not fled; they had died on the field, and of the five thousand knights who had followed Conan southward, not one left the field alive. And now the king himself stood at bay among the slashed bodies of his house-troops, his back against a heap of dead horses and men. Ophirean knights in gilded mail leaped their horses over mounds of corpses to slash at the solitary figure; squat Shemites with blue-black beards, and dark-faced Kothian knights ringed him on foot. The clangor of steel rose deafeningly; the black-mailed figure of the western king loomed among his swarming foes, dealing blows like a butcher wielding a great cleaver. Riderless horses raced down the field; about his iron-clad feet grew a ring of mangled corpses. His attackers drew back from his desperate savagery, panting and livid.

Now through the yelling, cursing lines rode the lords of the conquerors—Strabonus, with his broad dark face and crafty eyes; Amalrus, slender, fastidious, treacherous, dangerous as a cobra; and the lean vulture Tsotha-lanti, clad only in silken robes, his great black eyes glittering from a face that was like that of a bird of prey. Of this Kothian wizard dark tales were told; tousle-headed women in northern and western villages frightened children with his name, and rebellious slaves were brought to abased submission quicker than by the lash, with threat of being sold to him. Men said that he had a whole library of dark works bound in skin flayed from living human victims, and that in nameless pits below the hill whereon his palace sat, he trafficked with the powers of darkness, trading screaming girl slaves for unholy secrets. He was the real ruler of Koth.

Now he grinned bleakly as the kings reined back a safe distance from the grim iron-clad figure looming among the dead. Before the savage blue eyes blazing murderously from beneath the crested, dented helmet, the boldest shrank. Conan’s dark scarred face was darker yet with passion; his black armor was hacked to tatters and splashed with blood; his great sword red to the cross-piece. In this stress all the veneer of civilization had faded; it was a barbarian who faced his conquerors. Conan was a Cimmerian by birth, one of those fierce moody hillmen who dwelt in their gloomy, cloudy land in the north. His saga, which had led him to the throne of Aquilonia, was the basis of a whole cycle of hero-tales.

So now the kings kept their distance, and Strabonus called on his Shemitish archers to loose their arrows at his foe from a distance; his captains had fallen like ripe grain before the Cimmerian’s broadsword, and Strabonus, penurious of his knights as of his coins, was frothing with fury. But Tsotha shook his head.

“Take him alive.”

“Easy to say!” snarled Strabonus, uneasy lest in some way the black-mailed giant might hew a path to them through the spears. “Who can take a man-eating tiger alive? By Ishtar, his heel is on the necks of my finest swordsmen! It took seven years and stacks of gold to train each, and there they lie, so much kite’s meat. Arrows, I say!”

“Again, nay!” snapped Tsotha, swinging down from his horse. He laughed coldly. “Have you not learned by this time that my brain is mightier than any sword?”

He passed through the lines of the pikemen, and the giants in their steel caps and mail brigandines shrank back fearfully, lest they so much as touch the skirts of his robe. Nor were the plumed knights slower in making room for him. He stepped over the corpses and came face to face with the grim king. The hosts watched in tense silence, holding their breath. The black-armored figure loomed in terrible menace over the lean, silk-robed shape, the notched, dripping sword hovering on high.

“I offer you life, Conan,” said Tsotha, a cruel mirth bubbling at the back of his voice.

“I give you death, wizard,” snarled the king, and backed by iron muscles and ferocious hate the great sword swung in a stroke meant to shear Tsotha’s lean torso in half. But even as the hosts cried out, the wizard stepped in, too quick for the eye to follow, and apparently merely laid an open hand on Conan’s left forearm, from the ridged muscles of which the mail had been hacked away. The whistling blade veered from its arc and the mailed giant crashed heavily to earth, to lie motionless. Tsotha laughed silently.

“Take him up and fear not; the lion’s fangs are drawn.”

The kings reined in and gazed in awe at the fallen lion. Conan lay stiffly, like a dead man, but his eyes glared up at them, wide open, and blazing with helpless fury.

“What have you done to him?” asked Amalrus uneasily.

Tsotha displayed a broad ring of curious design on his finger. He pressed his fingers together and on the inner side of the ring a tiny steel fang darted out like a snake’s tongue.

“It is steeped in the juice of the purple lotus which grows in the ghost-haunted swamps of southern Stygia,” said the magician. “Its touch produces temporary paralysis. Put him in chains and lay him in a chariot. The sun sets and it is time we were on the road for Khorshemish.”

Strabonus turned to his general Arbanus.

“We return to Khorshemish with the wounded. Only a troop of the royal cavalry will accompany us. Your orders are to march at dawn to the Aquilonian border, and invest the city of Shamar. The Ophireans will supply you with food along the march. We will rejoin you as soon as possible, with reinforcements.”

So the host, with its steel-sheathed knights, its pikemen and archers and camp-servants, went into camp in the meadowlands near the battlefield. And through the starry night the two kings and the sorcerer who was greater than any king rode to the capital of Strabonus, in the midst of the glittering palace troop, and accompanied by a long line of chariots, loaded with the wounded. In one of these chariots lay Conan, king of Aquilonia, weighted with chains, the tang of defeat in his mouth, the blind fury of a trapped tiger in his soul.

The poison which had frozen his mighty limbs to helplessness had not paralyzed his brain. As the chariot in which he lay rumbled over the meadowlands, his mind revolved maddeningly about his defeat. Amalrus had sent an emissary imploring aid against Strabonus, who, he said, was ravaging his western domain, which lay like a tapering wedge between the border of Aquilonia and the vast southern kingdom of Koth. He asked only a thousand horsemen and the presence of Conan, to hearten his demoralized subjects. Conan now mentally blasphemed. In his generosity he had come with five times the number the treacherous monarch had asked. In good faith he had ridden into Ophir, and had been confronted by the supposed rivals allied against him. It spoke significantly of his prowess that they had brought up a whole host to trap him and his five thousand.

A red cloud veiled his vision; his veins swelled with fury and in his temples a pulse throbbed maddeningly. In all his life he had never known greater and more helpless wrath. In swift-moving scenes the pageant of his life passed fleetingly before his mental eye—a panorama wherein moved shadowy figures which were himself, in many guises and conditions—a skin-clad barbarian; a mercenary swordsman in horned helmet and scale-mail corselet; a corsair in a dragon-prowed galley that trailed a crimson wake of blood and pillage along southern coasts; a captain of hosts in burnished steel, on a rearing black charger; a king on a golden throne with the lion banner flowing above, and throngs of gay-hued courtiers and ladies on their knees. But always the jouncing and rumbling of the chariot brought his thoughts back to revolve with maddening monotony about the treachery of Amalrus and the sorcery of Tsotha. The veins nearly burst in his temples and cries of the wounded in the chariots filled him with ferocious satisfaction.

Before midnight they crossed the Ophirean border and at dawn the spires of Khorshemish stood up gleaming and rose-tinted on the south-eastern horizon, the slim towers overawed by the grim scarlet citadel that at a distance was like a splash of bright blood in the sky. That was the castle of Tsotha. Only one narrow street, paved with marble and guarded by heavy iron gates, led up to it, where it crowned the hill dominating the city. The sides of that hill were too sheer to be climbed elsewhere. From the walls of the citadel one could look down on the broad white streets of the city, on minaretted mosques, shops, temples, mansions, and markets. One could look down, too, on the palaces of the king, set in broad gardens, high-walled, luxurious riots of fruit trees and blossoms, through which artificial streams murmured, and silvery fountains rippled incessantly. Over all brooded the citadel, like a condor stooping above its prey, intent on its own dark meditations.

The mighty gates between the huge towers of the outer wall clanged open, and the king rode into his capital between lines of glittering spearmen, while fifty trumpets pealed salute. But no throngs swarmed the white-paved streets to fling roses before the conqueror’s hoofs. Strabonus had raced ahead of news of the battle, and the people, just rousing to the occupations of the day, gaped to see their king returning with a small retinue, and were in doubt as to whether it portended victory or defeat.

Conan, life sluggishly moving in his veins again, craned his neck from the chariot floor to view the wonders of this city which men called the Queen of the South. He had thought to ride some day through these golden-chased gates at the head of his steel-clad squadrons, with the great lion banner flowing over his helmeted head. Instead he entered in chains, stripped of his armor, and thrown like a captive slave on the bronze floor of his conqueror’s chariot. A wayward devilish mirth of mockery rose above his fury, but to the nervous soldiers who drove the chariot his laughter sounded like the muttering of a rousing lion.

Gleaming shell of an outworn lie; fable of Right divine—

You gained your crowns by heritage, but Blood was the price of mine.

The throne that I won by blood and sweat, by Crom, I will not sell

For promise of valleys filled with gold, or threat of the Halls of Hell!

—The Road of Kings.

In the citadel, in a chamber with a domed ceiling of carven jet, and the fretted arches of doorways glimmering with strange dark jewels, a strange conclave came to pass. Conan of Aquilonia, blood from unbandaged wounds caking his huge limbs, faced his captors. On either side of him stood a dozen black giants, grasping their long-shafted axes. In front of him stood Tsotha, and on divans lounged Strabonus and Amalrus in their silks and gold, gleaming with jewels, naked slave-boys beside them pouring wine into cups carved of a single sapphire. In strong contrast stood Conan, grim, blood-stained, naked but for a loin-cloth, shackles on his mighty limbs, his blue eyes blazing beneath the tangled black mane which fell over his low broad forehead. He dominated the scene, turning to tinsel the pomp of the conquerors by the sheer vitality of his elemental personality, and the kings in their pride and splendor were aware of it each in his secret heart, and were not at ease. Only Tsotha was not disturbed.

“Our desires are quickly spoken, king of Aquilonia,” said Tsotha. “It is our wish to extend our empire.”

“And so you want to swine my kingdom,” rasped Conan.

“What are you but an adventurer, seizing a crown to which you had no more claim than any other wandering barbarian?” parried Amalrus. “We are prepared to offer you suitable compensation—”

“Compensation!” It was a gust of deep laughter from Conan’s mighty chest. “The price of infamy and treachery! I am a barbarian, so I shall sell my kingdom and its people for life and your filthy gold? Ha! How did you come to your crown, you and that black-faced pig beside you? Your fathers did the fighting and the suffering, and handed their crowns to you on golden platters. What you inherited without lifting a finger—except to poison a few brothers—I fought for.

“You sit on satin and guzzle wine the people sweat for, and talk of divine rights of sovereignty—bah! I climbed out of the abyss of naked barbarism to the throne and in that climb I spilt my blood as freely as I spilt that of others. If either of us has the right to rule men, by Crom, it is I! How have you proved yourselves my superiors?

“I found Aquilonia in the grip of a pig like you—one who traced his genealogy for a thousand years. The land was torn with the wars of the barons, and the people cried out under oppression and taxation. Today no Aquilonian noble dares maltreat the humblest of my subjects, and the taxes of the people are lighter than anywhere else in the world.

“What of you? Your brother, Amalrus, holds the eastern half of your kingdom, and defies you. And you, Strabonus, your soldiers are even now besieging castles of a dozen or more rebellious barons. The people of both your kingdoms are crushed into the earth by tyrannous taxes and levies. And you would loot mine—ha! Free my hands and I’ll varnish this floor with your brains!”

Tsotha grinned bleakly to see the rage of his kingly companions.

“All this, truthful though it be, is beside the point. Our plans are no concern of yours. Your responsibility is at an end when you sign this parchment, which is an abdication in favor of Prince Arpello of Pellia. We will give you arms and horse, and five thousand golden lunas, and escort you to the eastern frontier.”

“Setting me adrift where I was when I rode into Aquilonia to take service in her armies, except with the added burden of a traitor’s name!” Conan’s laugh was like the deep short bark of a timber wolf. “Arpello, eh? I’ve had suspicions of that butcher of Pellia. Can you not even steal and pillage frankly and honestly, but you must have an excuse, however thin? Arpello claims a trace of royal blood; so you use him as an excuse for theft, and a satrap to rule through. I’ll see you in hell first.”

“You’re a fool!” exclaimed Amalrus. “You are in our hands, and we can take both crown and life at our pleasure!”

Conan’s answer was neither kingly nor dignified, but characteristically instinctive in the man, whose barbaric nature had never been submerged in his adopted culture. He spat full in Amalrus’ eyes. The king of Ophir leaped up with a scream of outraged fury, groping for his slender sword. Drawing it, he rushed at the Cimmerian, but Tsotha intervened.

“Wait, your majesty; this man is my prisoner.”

“Aside, wizard!” shrieked Amalrus, maddened by the glare in the Cimmerian’s blue eyes.

“Back, I say!” roared Tsotha, roused to awesome wrath. His lean hand came from his wide sleeve and cast a shower of dust into the Ophirean’s contorted face. Amalrus cried out and staggered back, clutching at his eyes, the sword falling from his hand. He dropped limply on the divan, while the Kothian guards looked on stolidly and King Strabonus hurriedly gulped another goblet of wine, holding it with hands that trembled. Amalrus lowered his hands and shook his head violently, intelligence slowly sifting back into his grey eyes.

“I went blind,” he growled. “What did you do to me, wizard?”

“Merely a gesture to convince you who was the real master,” snapped Tsotha, the mask of his formal pretense dropped, revealing the naked evil personality of the man. “Strabonus has learned his lesson—let you learn yours. It was but a dust I found in a Stygian tomb which I flung into your eyes—if I brush out their sight again, I will leave you to grope in darkness for the rest of your life.”

Amalrus shrugged his shoulders, smiled whimsically and reached for a goblet, dissembling his fear and fury. A polished diplomat, he was quick to regain his poise. Tsotha turned to Conan, who had stood imperturbably during the episode. At the wizard’s gesture, the blacks laid hold of their prisoner and marched him behind Tsotha, who led the way out of the chamber through an arched doorway into a winding corridor, whose floor was of many-hued mosaics, whose walls were inlaid with gold tissue and silver chasing, and from whose fretted arched ceiling swung golden censers, filling the corridor with dreamy perfumed clouds. They turned down a smaller corridor, done in jet and black jade, gloomy and awful, which ended at a brass door, over whose arch a human skull grinned horrifically. At this door stood a fat repellent figure, dangling a bunch of keys—Tsotha’s chief eunuch, Shukeli, of whom grisly tales were whispered—a man with whom a bestial lust for torture took the place of normal human passions.

The brass door let onto a narrow stair that seemed to wind down into the very bowels of the hill on which the citadel stood. Down these stairs went the band, to halt at last at an iron door, the strength of which seemed unnecessary. Evidently it did not open on outer air, yet it was built as if to withstand the battering of mangonels and rams. Shukeli opened it, and as he swung back the ponderous portal, Conan noted the evident uneasiness among the black giants who guarded him; nor did Shukeli seem altogether devoid of nervousness as he peered into the darkness beyond. Inside the great door there was a second barrier, composed of heavy steel bars. It was fastened by an ingenious bolt which had no lock and could be worked only from the outside; this bolt shot back, the grille slid into the wall. They passed through, into a broad corridor, the floor, walls and arched ceiling of which seemed to be cut out of solid stone. Conan knew he was far underground, even below the hill itself. The darkness pressed in on the guardsmen’s torches like a sentient, animate thing.

They made the king fast to a ring in the stone wall. Above his head in a niche in the wall they placed a torch, so that he stood in a dim semicircle of light. The blacks were anxious to be gone; they muttered among themselves, and cast fearful glances at the darkness. Tsotha motioned them out, and they filed through the door in stumbling haste, as if fearing that the darkness might take tangible form and spring upon their backs. Tsotha turned toward Conan, and the king noticed uneasily that the wizard’s eyes shone in the semi-darkness, and that his teeth much resembled the fangs of a wolf, gleaming whitely in the shadows.

“And so, farewell, barbarian,” mocked the sorcerer. “I must ride to Shamar, and the siege. In ten days I will be in your palace in Tamar, with my warriors. What word from you shall I say to your women, before I flay their dainty skins for scrolls whereon to chronicle the triumphs of Tsotha-lanti?”

Conan answered with a searing Cimmerian curse that would have burst the eardrums of an ordinary man, and Tsotha laughed thinly and withdrew. Conan had a glimpse of his vulture-like figure through the thick-set bars, as he slid home the grate; then the heavy outer door clanged, and silence fell like a pall.

The Lion strode through the Halls of Hell;

Across his path grim shadows fell

Of many a mowing, nameless shape—

Monsters with dripping jaws agape.

The darkness shuddered with scream and yell

When the Lion stalked through the Halls of Hell.

—Old Ballad.

King Conan tested the ring in the wall and the chain that bound him. His limbs were free, but he knew that his shackles were beyond even his iron strength. The links of the chain were as thick as his thumb and were fastened to a band of steel about his waist, a band broad as his hand and half an inch thick. The sheer weight of his shackles would have slain a lesser man with exhaustion. The locks that held band and chain were massive affairs that a sledge-hammer could hardly have dinted. As for the ring, evidently it went clear through the wall and was clinched on the other side.

Conan cursed and panic surged through him as he glared into the darkness that pressed against the half-circle of light. All the superstitious dread of the barbarian slept in his soul, untouched by civilized logic. His primitive imagination peopled the subterranean darkness with grisly shapes. Besides, his reason told him that he had not been placed there merely for confinement. His captors had no reason to spare him. He had been placed in these pits for a definite doom. He cursed himself for his refusal of their offer, even while his stubborn manhood revolted at the thought, and he knew that were he taken forth and given another chance, his reply would be the same. He would not sell his subjects to the butcher. And yet it had been with no thought of any one’s gain but his own that he had seized the kingdom originally. Thus subtly does the instinct of sovereign responsibility enter even a red-handed plunderer sometimes.

Conan thought of Tsotha’s last abominable threat, and groaned in sick fury, knowing it was no idle boast. Men and women were to the wizard no more than the writhing insect is to the scientist. Soft white hands that had caressed him, red lips that had been pressed to his, dainty white bosoms that had quivered to his hot fierce kisses, to be stripped of their delicate skin, white as ivory and pink as young petals—from Conan’s lips burst a yell so frightful and inhuman in its mad fury that a listener would have stared in horror to know that it came from a human throat.

The shuddering echoes made him start and brought back his own situation vividly to the king. He glared fearsomely at the outer gloom, and thought of the grisly tales he had heard of Tsotha’s necromantic cruelty, and it was with an icy sensation down his spine that he realized that these must be the very Halls of Horror named in shuddering legendry, the tunnels and dungeons wherein Tsotha performed horrible experiments with beings human, bestial, and, it was whispered, demoniac, tampering blasphemously with the naked basic elements of life itself. Rumor said that the mad poet Rinaldo had visited these pits, and been shown horrors by the wizard, and that the nameless monstrosities of which he hinted in his awful poem, The Song of the Pit, were no mere fantasies of a disordered brain. That brain had crashed to dust beneath Conan’s battle-axe on the night the king had fought for his life with the assassins the mad rhymer had led into the betrayed palace, but the shuddersome words of that grisly song still rang in the king’s ears as he stood there in his chains.

Even with the thought the Cimmerian was frozen by a soft rustling sound, blood-freezing in its implication. He tensed in an attitude of listening, painful in its intensity. An icy hand stroked his spine. It was the unmistakable sound of pliant scales slithering softly over stone. Cold sweat beaded his skin, as beyond the ring of dim light he saw a vague and colossal form, awful even in its indistinctness. It reared upright, swaying slightly, and yellow eyes burned icily on him from the shadows. Slowly a huge, hideous, wedge-shaped head took form before his dilated eyes, and from the darkness oozed, in flowing scaly coils, the ultimate horror of reptilian development.

It was a snake that dwarfed all Conan’s previous ideas of snakes. Eighty feet it stretched from its pointed tail to its triangular head, which was bigger than that of a horse. In the dim light its scales glistened coldly, white as hoar-frost. Surely this reptile was one born and grown in darkness, yet its eyes were full of evil and sure sight. It looped its titan coils in front of the captive, and the great head on the arching neck swayed a matter of inches from his face. Its forked tongue almost brushed his lips as it darted in and out, and its fetid odor made his senses reel with nausea. The great yellow eyes burned into his, and Conan gave back the glare of a trapped wolf. He fought against the mad impulse to grasp the great arching neck in his tearing hands. Strong beyond the comprehension of civilized man, he had broken the neck of a python in a fiendish battle on the Stygian coast, in his corsair days. But this reptile was venomous; he saw the great fangs, a foot long, curved like scimitars. From them dripped a colorless liquid that he instinctively knew was death. He might conceivably crush that wedge-shaped skull with a desperate clenched fist, but he knew that at his first hint of movement, the monster would strike like lightning.

It was not because of any logical reasoning process that Conan remained motionless, since reason might have told him—since he was doomed anyway—to goad the snake into striking and get it over with; it was the blind black instinct of self-preservation that held him rigid as a statue blasted out of iron. Now the great barrel reared up and the head was poised high above his own, as the monster investigated the torch. A drop of venom fell on his naked thigh, and the feel of it was like a white-hot dagger driven into his flesh. Red jets of agony shot through Conan’s brain, yet he held himself immovable; not by the twitching of a muscle or the flicker of an eyelash did he betray the pain of the hurt that left a scar he bore to the day of his death.

The serpent swayed above him, as if seeking to ascertain whether there were in truth life in this figure which stood so death-like still. Then suddenly, unexpectedly, the outer door, all but invisible in the shadows, clanged stridently. The serpent, suspicious as all its kind, whipped about with a quickness incredible for its bulk, and vanished with a long-drawn slithering down the corridor. The door swung open and remained open. The grille was withdrawn and a huge dark figure was framed in the glow of torches outside. The figure glided in, pulling the grille partly to behind it, leaving the bolt poised. As it moved into the light of the torch over Conan’s head, the king saw that it was a gigantic black man, stark naked, bearing in one hand a huge sword and in the other a bunch of keys. The black spoke in a sea-coast dialect, and Conan replied; he had learned the jargon while a corsair on the coasts of Kush.

“Long have I wished to meet you, Amra,” the black gave Conan the name—Amra, the Lion—by which the Cimmerian had been known to the Kushites in his piratical days. The slave’s woolly skull split in an animal-like grin, showing white tusks, but his eyes glinted redly in the torchlight. “I have dared much for this meeting! Look! The keys to your chains! I stole them from Shukeli. What will you give me for them?”

He dangled the keys in front of Conan’s eyes.

“Ten thousand golden lunas,” answered the king quickly, new hope surging fiercely in his breast.

“Not enough!” cried the black, a ferocious exultation shining on his ebon countenance. “Not enough for the risks I take. Tsotha’s pets might come out of the dark and eat me, and if Shukeli finds out I stole his keys, he’ll hang me up by my—well, what will you give me?”

“Fifteen thousand lunas and a palace in Poitain,” offered the king.

The black yelled and stamped in a frenzy of barbaric gratification.

“More!” he cried. “Offer me more! What will you give me?”

“You black dog!” A red mist of fury swept across Conan’s eyes. “Were I free I’d give you a broken back! Did Shukeli send you here to mock me?”

“Shukeli knows nothing of my coming, white man,” answered the black, craning his thick neck to peer into Conan’s savage eyes. “I know you from of old, since the days when I was a chief among a free people, before the Stygians took me and sold me into the north. Do you not remember the sack of Abombi, when your sea-wolves swarmed in? Before the palace of King Ajaga you slew a chief and a chief fled from you. It was my brother who died; it was I who fled. I demand of you a blood-price, Amra!”

“Free me and I’ll pay you your weight in gold pieces,” growled Conan.

The red eyes glittered, the white teeth flashed wolfishly in the torchlight.

“Aye, you white dog, you are like all your race; but to a black man gold can never pay for blood. The price I ask is—your head!”

The last word was a maniacal shriek that sent the echoes shivering. Conan tensed, unconsciously straining against his shackles in his abhorrence of dying like a sheep; then he was frozen by a greater horror. Over the black’s shoulder he saw a vague horrific form swaying in the darkness.

“Tsotha will never know!” laughed the black fiendishly, too engrossed in his gloating triumph to take heed of anything else, too drunk with hate to know that Death swayed behind his shoulder. “He will not come into the vaults until the demons have torn your bones from their chains. I will have your head, Amra!”

He braced his knotted legs like ebon columns and swung up the massive sword in both hands, his great black muscles rolling and cracking in the torchlight. And at that instant the titanic shadow behind him darted down and out, and the wedge-shaped head smote with an impact that re-echoed down the tunnels. Not a sound came from the thick blubbery lips that flew wide in fleeting agony. With the thud of the stroke, Conan saw the life go out of the wide black eyes with the suddenness of a candle blown out. The blow knocked the great black body clear across the corridor and horribly the gigantic sinuous shape whipped around it in glistening coils that hid it from view, and the snap and splintering of bones came plainly to Conan’s ears. Then something made his heart leap madly. The sword and the keys had flown from the black’s hands to crash and jangle on the stone—and the keys lay almost at the king’s feet.

He tried to bend to them, but the chain was too short; almost suffocated by the mad pounding of his heart, he slipped one foot from its sandal, and gripped them with his toes; drawing his foot up, he grasped them fiercely, barely stifling the yell of ferocious exultation that rose instinctively to his lips.

An instant’s fumbling with the huge locks and he was free. He caught up the fallen sword and glared about. Only empty darkness met his eyes, into which the serpent had dragged a mangled, tattered object that only faintly resembled a human body. Conan turned to the open door. A few quick strides brought him to the threshold—a squeal of high-pitched laughter shrilled through the vaults, and the grille shot home under his very fingers, the bolt crashed down. Through the bars peered a face like a fiendishly mocking carven gargoyle—Shukeli the eunuch, who had followed his stolen keys. Surely he did not, in his gloating, see the sword in the prisoner’s hand. With a terrible curse Conan struck as a cobra strikes; the great blade hissed between the bars and Shukeli’s laughter broke in a death-scream. The fat eunuch bent at the middle, as if bowing to his killer, and crumpled like tallow, his pudgy hands clutching vainly at his spilling entrails.

Conan snarled in savage satisfaction; but he was still a prisoner. His keys were futile against the bolt which could be worked only from the outside. His experienced touch told him the bars were hard as the sword; an attempt to hew his way to freedom would only splinter his one weapon. Yet he found dents on those adamantine bars, like the marks of incredible fangs, and wondered with an involuntary shudder what nameless monsters had so terribly assailed the barriers. Regardless, there was but one thing for him to do, and that was to seek some other outlet. Taking the torch from the niche, he set off down the corridor, sword in hand. He saw no sign of the serpent or its victim, only a great smear of blood on the stone floor.

Darkness stalked on noiseless feet about him, scarcely driven back by his flickering torch. On either hand he saw dark openings, but he kept to the main corridor, watching the floor ahead of him carefully, lest he fall into some pit. And suddenly he heard the sound of a woman, weeping piteously. Another of Tsotha’s victims, he thought, cursing the wizard anew, and turning aside, followed the sound down a smaller tunnel, dank and damp.

The weeping grew nearer as he advanced, and lifting his torch he made out a vague shape in the shadows. Stepping closer, he halted in sudden horror at the amorphic bulk which sprawled before him. Its unstable outlines somewhat suggested an octopus, but its malformed tentacles were too short for its size, and its substance was a quaking, jelly-like stuff which made him physically sick to look at. From among this loathsome gelid mass reared up a frog-like head, and he was frozen with nauseated horror to realize that the sound of weeping was coming from those obscene blubbery lips. The noise changed to an abominable high-pitched tittering as the great unstable eyes of the monstrosity rested on him, and it hitched its quaking bulk toward him. He backed away and fled up the tunnel, not trusting his sword. The creature might be composed of terrestrial matter, but it shook his very soul to look upon it, and he doubted the power of man-made weapons to harm it. For a short distance he heard it flopping and floundering after him, screaming with horrible laughter. The unmistakably human note in its mirth almost staggered his reason. It was exactly such laughter as he had heard bubble obscenely from the fat lips of the salacious women of Shadizar, City of Wickedness, when captive girls were stripped naked on the public auction block. By what hellish arts had Tsotha brought this unnatural being into life? Conan felt vaguely that he had looked on blasphemy against the eternal laws of nature.

He ran toward the main corridor, but before he reached it he crossed a sort of small square chamber, where two tunnels crossed. As he reached this chamber, he was flashingly aware of some small squat bulk on the floor ahead of him; then before he could check his flight or swerve aside, his foot struck something yielding that squalled shrilly, and he was precipitated headlong, the torch flying from his hand and being extinguished as it struck the stone floor. Half stunned by his fall, Conan rose and groped in the darkness. His sense of direction was confused, and he was unable to decide in which direction lay the main corridor. He did not look for the torch, as he had no means of rekindling it. His groping hands found the openings of the tunnels, and he chose one at random. How long he traversed it in utter darkness, he never knew, but suddenly his barbarian’s instinct of near peril halted him short.

He had the same feeling he had had when standing on the brink of great precipices in the darkness. Dropping to all fours, he edged forward, and presently his outflung hand encountered the edge of a well, into which the tunnel floor dropped abruptly. As far down as he could reach the sides fell away sheerly, dank and slimy to his touch. He stretched out an arm in the darkness and could barely touch the opposite edge with the point of his sword. He could leap across it, then, but there was no point in that. He had taken the wrong tunnel and the main corridor lay somewhere behind him.

Even as he thought this, he felt a faint movement of air; a shadowy wind, rising from the well, stirred his black mane. Conan’s skin crawled. He tried to tell himself that this well connected somehow with the outer world, but his instincts told him it was a thing unnatural. He was not merely inside the hill; he was below it, far below the level of the city streets. How then could an outer wind find its way into the pits and blow up from below? A faint throbbing pulsed on that ghostly wind, like drums beating, far, far below. A strong shudder shook the king of Aquilonia.

He rose to his feet and backed away, and as he did something floated up out of the well. What it was, Conan did not know. He could see nothing in the darkness, but he distinctly felt a presence—an invisible, intangible intelligence which hovered malignly near him. Turning, he fled the way he had come. Far ahead he saw a tiny red spark. He headed for it, and long before he thought to have reached it, he caromed headlong into a solid wall, and saw the spark at his feet. It was his torch, the flame extinguished, but the end a glowing coal. Carefully he took it up and blew upon it, fanning it into flame again. He gave a sigh as the tiny blaze leaped up. He was back in the chamber where the tunnels crossed, and his sense of direction came back.

He located the tunnel by which he had left the main corridor, and even as he started toward it, his torch flame flickered wildly as if blown upon by unseen lips. Again he felt a presence, and he lifted his torch, glaring about.

He saw nothing; yet he sensed, somehow, an invisible, bodiless thing that hovered in the air, dripping slimily and mouthing obscenities that he could not hear but was in some instinctive way aware of. He swung viciously with his sword and it felt as if he were cleaving cobwebs. A cold horror shook him then, and he fled down the tunnel, feeling a foul burning breath on his naked back as he ran.

But when he came out into the broad corridor, he was no longer aware of any presence, visible or invisible. Down it he went, momentarily expecting fanged and taloned fiends to leap at him from the darkness. The tunnels were not silent. From the bowels of the earth in all directions came sounds that did not belong in a sane world. There were titterings, squeals of demoniac mirth, long shuddering howls, and once the unmistakable squalling laughter of a hyena ended awfully in human words of shrieking blasphemy. He heard the pad of stealthy feet, and in the mouths of the tunnels caught glimpses of shadowy forms, monstrous and abnormal in outline.

It was as if he had wandered into hell—a hell of Tsotha-lanti’s making. But the shadowy things did not come into the great corridor, though he distinctly heard the greedy sucking-in of slavering lips, and felt the burning glare of hungry eyes. And presently he knew why. A slithering sound behind him electrified him, and he leaped to the darkness of a near-by tunnel, shaking out his torch. Down the corridor he heard the great serpent crawling, sluggish from its recent grisly meal. From his very side something whimpered in fear and slunk away in the darkness. Evidently the main corridor was the great snake’s hunting-ground and the other monsters gave it room.

To Conan the serpent was the least horror of them; he almost felt a kinship with it when he remembered the weeping, tittering obscenity, and the dripping, mouthing thing that came out of the well. At least it was of earthly matter; it was a crawling death, but it threatened only physical extinction, whereas these other horrors menaced mind and soul as well.

After it had passed on down the corridor he followed, at what he hoped was a safe distance, blowing his torch into flame again. He had not gone far when he heard a low moan that seemed to emanate from the black entrance of a tunnel near by. Caution warned him on, but curiosity drove him to the tunnel, holding high the torch that was now little more than a stump. He was braced for the sight of anything, yet what he saw was what he had least expected. He was looking into a broad cell, and a space of this was caged off with closely set bars extending from floor to ceiling, set firmly in the stone. Within these bars lay a figure, which, as he approached, he saw was either a man, or the exact likeness of a man, twined and bound about with the tendrils of a thick vine which seemed to grow through the solid stone of the floor. It was covered with strangely pointed leaves and crimson blossoms—not the satiny red of natural petals, but a livid, unnatural crimson, like a perversity of flower-life. Its clinging, pliant branches wound about the man’s naked body and limbs, seeming to caress his shrinking flesh with lustful avid kisses. One great blossom hovered exactly over his mouth. A low bestial moaning drooled from the loose lips; the head rolled as if in unbearable agony, and the eyes looked full at Conan. But there was no light of intelligence in them; they were blank, glassy, the eyes of an idiot.

Now the great crimson blossom dipped and pressed its petals over the writhing lips. The limbs of the wretch twisted in anguish; the tendrils of the plant quivered as if in ecstasy, vibrating their full snaky lengths. Waves of changing hues surged over them; their color grew deeper, more venomous.

Conan did not understand what he saw, but he knew that he looked on Horror of some kind. Man or demon, the suffering of the captive touched Conan’s wayward and impulsive heart. He sought for entrance and found a grille-like door in the bars, fastened with a heavy lock, for which he found a key among the keys he carried, and entered. Instantly the petals of the livid blossoms spread like the hood of a cobra, the tendrils reared menacingly and the whole plant shook and swayed toward him. Here was no blind growth of natural vegetation. Conan sensed a malignant intelligence; the plant could see him, and he felt its hate emanate from it in almost tangible waves. Stepping warily nearer, he marked the root-stem, a repulsively supple stalk thicker than his thigh, and even as the long tendrils arched toward him with a rattle of leaves and hiss, he swung his sword and cut through the stem with a single stroke.

Instantly the wretch in its clutches was thrown violently aside as the great vine lashed and knotted like a beheaded serpent, rolling into a huge irregular ball. The tendrils thrashed and writhed, the leaves shook and rattled like castanets, and the petals opened and closed convulsively; then the whole length straightened out limply, the vivid colors paled and dimmed, a reeking white liquid oozed from the severed stump.

Conan stared, spellbound; then a sound brought him round, sword lifted. The freed man was on his feet, surveying him. Conan gaped in wonder. No longer were the eyes in the worn face expressionless. Dark and meditative, they were alive with intelligence, and the expression of imbecility had dropped from the face like a mask. The head was narrow and well-formed, with a high splendid forehead. The whole build of the man was aristocratic, evident no less in his tall slender frame than in his small trim feet and hands. His first words were strange and startling.

“What year is this?” he asked, speaking Kothic.

“Today is the tenth day of the month Yuluk, of the year of the Gazelle,” answered Conan.

“Yagkoolan Ishtar!” murmured the stranger. “Ten years!” He drew a hand across his brow, shaking his head as if to clear his brain of cobwebs. “All is dim yet. After a ten-year emptiness, the mind can not be expected to begin functioning clearly at once. Who are you?”

“Conan, once of Cimmeria. Now king of Aquilonia.”

The other’s eyes showed surprize.

“Indeed? And Namedides?”

“I strangled him on his throne the night I took the royal city,” answered Conan.

A certain naivete in the king’s reply twitched the stranger’s lips.

“Pardon, your majesty. I should have thanked you for the service you have done me. I am like a man woken suddenly from sleep deeper than death and shot with nightmares of agony more fierce than hell, but I understand that you delivered me. Tell me—why did you cut the stem of the plant Yothga instead of tearing it up by the roots?”

“Because I learned long ago to avoid touching with my flesh that which I do not understand,” answered the Cimmerian.

“Well for you,” said the stranger. “Had you been able to tear it up, you might have found things clinging to the roots against which not even your sword would prevail. Yothga’s roots are set in hell.”

“But who are you?” demanded Conan.

“Men called me Pelias.”

“What!” cried the king. “Pelias the sorcerer, Tsotha-lanti’s rival, who vanished from the earth ten years ago?”

“Not entirely from the earth,” answered Pelias with a wry smile. “Tsotha preferred to keep me alive, in shackles more grim than rusted iron. He pent me in here with this devil-flower whose seeds drifted down through the black cosmos from Yag the Accursed, and found fertile field only in the maggot-writhing corruption that seethes on the floors of hell.

“I could not remember my sorcery and the words and symbols of my power, with that cursed thing gripping me and drinking my soul with its loathsome caresses. It sucked the contents of my mind day and night, leaving my brain as empty as a broken wine-jug. Ten years! Ishtar preserve us!”

Conan found no reply, but stood holding the stump of the torch, and trailing his great sword. Surely the man was mad—yet there was no madness in the dark eyes that rested so calmly on him.

“Tell me, is the black wizard in Khorshemish? But no—you need not reply. My powers begin to wake, and I sense in your mind a great battle and a king trapped by treachery. And I see Tsotha-lanti riding hard for the Tybor with Strabonus and the king of Ophir. So much the better. My art is too frail from the long slumber to face Tsotha yet. I need time to recruit my strength, to assemble my powers. Let us go forth from these pits.”

Conan jangled his keys discouragedly.

“The grille to the outer door is made fast by a bolt which can be worked only from the outside. Is there no other exit from these tunnels?”

“Only one, which neither of us would care to use, seeing that it goes down and not up,” laughed Pelias. “But no matter. Let us see to the grille.”

He moved toward the corridor with uncertain steps, as of long-unused limbs, which gradually became more sure. As he followed Conan remarked uneasily, “There is a cursed big snake creeping about this tunnel. Let us be wary lest we step into his mouth.”

“I remember him of old,” answered Pelias grimly, “the more as I was forced to watch while ten of my acolytes were fed to him. He is Satha, the Old One, chiefest of Tsotha’s pets.”

“Did Tsotha dig these pits for no other reason than to house his cursed monstrosities?” asked Conan.

“He did not dig them. When the city was founded three thousand years ago there were ruins of an earlier city on and about this hill. King Khossus v, the founder, built his palace on the hill, and digging cellars beneath it, came upon a walled-up doorway, which he broke into and discovered the pits, which were about as we see them now. But his grand vizier came to such a grisly end in them that Khossus in a fright walled up the entrance again. He said the vizier fell into a well—but he had the cellars filled in, and later abandoned the palace itself, and built himself another in the suburbs, from which he fled in a panic on discovering some black mold scattered on the marble floor of his palace one morning.

“He then departed with his whole court to the eastern corner of the kingdom and built a new city. The palace on the hill was not used and fell into ruins. When Akkutho i revived the lost glories of Khorshemish, he built a fortress there. It remained for Tsotha-lanti to rear the scarlet citadel and open the way to the pits again. Whatever fate overtook the grand vizier of Khossus, Tsotha avoided it. He fell into no well, though he did descend into a well he found, and came out with a strange expression which has not since left his eyes.

“I have seen that well, but I do not care to seek in it for wisdom. I am a sorcerer, and older than men reckon, but I am human. As for Tsotha—men say that a dancing-girl of Shadizar slept too near the pre-human ruins on Dagoth Hill and woke in the grip of a black demon; from that unholy union was spawned an accursed hybrid men call Tsotha-lanti—”

Conan cried out sharply and recoiled, thrusting his companion back. Before them rose the great shimmering white form of Satha, an ageless hate in its eyes. Conan tensed himself for one mad berserker onslaught—to thrust the glowing fagot into that fiendish countenance and throw his life into the ripping sword-stroke. But the snake was not looking at him. It was glaring over his shoulder at the man called Pelias, who stood with his arms folded, smiling. And in the great cold yellow eyes slowly the hate died out in a glitter of pure fear—the only time Conan ever saw such an expression in a reptile’s eyes. With a swirling rush like the sweep of a strong wind, the great snake was gone.

“What did he see to frighten him?” asked Conan, eyeing his companion uneasily.

“The scaled people see what escapes the mortal eye,” answered Pelias, cryptically. “You see my fleshly guise; he saw my naked soul.”

An icy trickle disturbed Conan’s spine, and he wondered if, after all, Pelias were a man, or merely another demon of the pits in a mask of humanity. He contemplated the advisability of driving his sword through his companion’s back without further hesitation. But while he pondered, they came to the steel grille, etched blackly in the torches beyond, and the body of Shukeli, still slumped against the bars in a curdled welter of crimson.

Pelias laughed, and his laugh was not pleasant to hear.

“By the ivory hips of Ishtar, who is our doorman? Lo, it is no less than the noble Shukeli, who hanged my young men by their feet and skinned them with squeals of laughter! Do you sleep, Shukeli? Why do you lie so stiffly, with your fat belly sunk in like a dressed pig’s?”

“He is dead,” muttered Conan, ill at ease to hear these wild words.

“Dead or alive,” laughed Pelias, “he shall open the door for us.”

He clapped his hands sharply and cried, “Rise, Shukeli! Rise from hell and rise from the bloody floor and open the door for your masters! Rise, I say!”

An awful groan reverberated through the vaults. Conan’s hair stood on end and he felt clammy sweat bead his hide. For the body of Shukeli stirred and moved, with infantile gropings of the fat hands. The laughter of Pelias was merciless as a flint hatchet, as the form of the eunuch reeled upright, clutching at the bars of the grille. Conan, glaring at him, felt his blood turn to ice, and the marrow of his bones to water; for Shukeli’s wide-open eyes were glassy and empty, and from the great gash in his belly his entrails hung limply to the floor. The eunuch’s feet stumbled among his entrails as he worked the bolt, moving like a brainless automaton. When he had first stirred, Conan had thought that by some incredible chance the eunuch was alive; but the man was dead—had been dead for hours.

Pelias sauntered through the opened grille, and Conan crowded through behind him, sweat pouring from his body, shrinking away from the awful shape that slumped on sagging legs against the grate it held open. Pelias passed on without a backward glance, and Conan followed him, in the grip of nightmare and nausea. He had not taken half a dozen strides when a sodden thud brought him round. Shukeli’s corpse lay limply at the foot of the grille.

“His task is done, and hell gapes for him again,” remarked Pelias pleasantly, politely affecting not to notice the strong shudder which shook Conan’s mighty frame.

He led the way up the long stairs, and through the brass skull-crowned door at the top. Conan gripped his sword, expecting a rush of slaves, but silence gripped the citadel. They passed through the black corridor and came into that in which the censers swung, billowing forth their everlasting incense. Still they saw no one.

“The slaves and soldiers are quartered in another part of the citadel,” remarked Pelias. “Tonight, their master being away, they doubtless lie drunk on wine or lotus-juice.”

Conan glanced through an arched, golden-silled window that let out upon a broad balcony, and swore in surprize to see the dark-blue star-flecked sky. It had been shortly after sunrise when he was thrown into the pits. Now it was past midnight. He could scarcely realize he had been so long underground. He was suddenly aware of thirst and a ravenous appetite. Pelias led the way into a gold-domed chamber, floored with silver, its lapis-lazuli walls pierced by the fretted arches of many doors.

With a sigh Pelias sank onto a silken divan.

“Gold and silks again,” he sighed. “Tsotha affects to be above the pleasures of the flesh, but he is half devil. I am human, despite my black arts. I love ease and good cheer—that’s how Tsotha trapped me. He caught me helpless with drink. Wine is a curse—by the ivory bosom of Ishtar, even as I speak of it, the traitor is here! Friend, please pour me a goblet—hold! I forgot that you are a king. I will pour.”

“The devil with that,” growled Conan, filling a crystal goblet and proffering it to Pelias. Then, lifting the jug, he drank deeply from the mouth, echoing Pelias’ sigh of satisfaction.

“The dog knows good wine,” said Conan, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “But by Crom, Pelias, are we to sit here until his soldiers awake and cut our throats?”

“No fear,” answered Pelias. “Would you like to see how fortune holds with Strabonus?”

Blue fire burned in Conan’s eyes, and he gripped his sword until his knuckles showed blue. “Oh, to be at sword-points with him!” he rumbled.

Pelias lifted a great shimmering globe from an ebony table.

“Tsotha’s crystal. A childish toy, but useful when there is lack of time for higher science. Look in, your majesty.”

He laid it on the table before Conan’s eyes. The king looked into cloudy depths which deepened and expanded. Slowly images crystallized out of mist and shadows. He was looking on a familiar landscape. Broad plains ran to a wide winding river, beyond which the level lands ran up quickly into a maze of low hills. On the northern bank of the river stood a walled town, guarded by a moat connected at each end with the river.

“By Crom!” ejaculated Conan. “It’s Shamar! The dogs besiege it!”

The invaders had crossed the river; their pavilions stood in the narrow plain between the city and the hills. Their warriors swarmed about the walls, their mail gleaming palely under the moon. Arrows and stones rained on them from the towers and they staggered back, but came on again.

Even as Conan cursed, the scene changed. Tall spires and gleaming domes stood up in the mist, and he looked on his own capital of Tamar, where all was confusion. He saw the steel-clad knights of Poitain, his staunchest supporters, riding out of the gate, hooted and hissed by the multitude which swarmed the streets. He saw looting and rioting, and men-at-arms whose shields bore the insignia of Pellia, manning the towers and swaggering through the markets. Over all, like a fantasmal mirage, he saw the dark, triumphant face of Prince Arpello of Pellia. The images faded.

“So!” raved Conan. “My people turn on me the moment my back is turned—”

“Not entirely,” broke in Pelias. “They have heard that you are dead. There is no one to protect them from outer enemies and civil war, they think. Naturally, they turn to the strongest noble, to avoid the horrors of anarchy. They do not trust the Poitanians, remembering former wars. But Arpello is on hand, and the strongest prince of the central provinces.”

“When I come to Aquilonia again he will be but a headless corpse rotting on Traitor’s Common,” Conan ground his teeth.

“Yet before you can reach your capital,” reminded Pelias, “Strabonus may be before you. At least his riders will be ravaging your kingdom.”

“True!” Conan paced the chamber like a caged lion. “With the fastest horse I could not reach Shamar before midday. Even there I could do no good except to die with the people, when the town falls—as fall it will in a few days at most. From Shamar to Tamar is five days’ ride, even if you kill your horses on the road. Before I could reach my capital and raise an army, Strabonus would be hammering at the gates; because raising an army is going to be hell—all my damnable nobles will have scattered to their own cursed fiefs at the word of my death. And since the people have driven out Trocero of Poitain, there’s none to keep Arpello’s greedy hands off the crown—and the crown-treasure. He’ll hand the country over to Strabonus, in return for a mock-throne—and as soon as Strabonus’ back is turned, he’ll stir up revolt. But the nobles won’t support him, and it will only give Strabonus excuse for annexing the kingdom openly. Oh Crom, Ymir, and Set! If I but had wings to fly like lightning to Tamar!”

Pelias, who sat tapping the jade table-top with his finger-nails, halted suddenly, and rose as with a definite purpose, beckoning Conan to follow. The king complied, sunk in moody thoughts, and Pelias led the way out of the chamber and up a flight of marble, gold-worked stairs that let out on the pinnacle of the citadel, the roof of the tallest tower. It was night, and a strong wind was blowing through the star-filled skies, stirring Conan’s black mane. Far below them twinkled the lights of Khorshemish, seemingly farther away than the stars above them. Pelias seemed withdrawn and aloof here, one in cold unhuman greatness with the company of the stars.

“There are creatures,” said Pelias, “not alone of earth and sea, but of air and the far reaches of the skies as well, dwelling apart, unguessed of men. Yet to him who holds the Master-words and Signs and the Knowledge underlying all, they are not malignant nor inaccessible. Watch, and fear not.”

He lifted his hands to the skies and sounded a long weird call that seemed to shudder endlessly out into space, dwindling and fading, yet never dying out, only receding farther and farther into some unreckoned cosmos. In the silence that followed, Conan heard a sudden beat of wings in the stars, and recoiled as a huge bat-like creature alighted beside him. He saw its great calm eyes regarding him in the starlight; he saw the forty-foot spread of its giant wings. And he saw it was neither bat nor bird.

“Mount and ride,” said Pelias. “By dawn it will bring you to Tamar.”

“By Crom!” muttered Conan. “Is this all a nightmare from which I shall presently awaken in my palace at Tamar? What of you? I would not leave you alone among your enemies.”

“Be at ease regarding me,” answered Pelias. “At dawn the people of Khorshemish will know they have a new master. Doubt not what the gods have sent you. I will meet you in the plain by Shamar.”

Doubtfully Conan clambered upon the ridged back, gripping the arched neck, still convinced that he was in the grasp of a fantastic nightmare. With a great rush and thunder of titan wings, the creature took the air, and the king grew dizzy as he saw the lights of the city dwindle far below him.

“The sword that slays the king cuts the cords of the empire.”

—Aquilonian proverb.

The streets of Tamar swarmed with howling mobs, shaking fists and rusty pikes. It was the hour before dawn of the second day after the battle of Shamu, and events had occurred so swiftly as to daze the mind. By means known only to Tsotha-lanti, word had reached Tamar of the king’s death, within half a dozen hours after the battle. Chaos had resulted. The barons had deserted the royal capital, galloping away to secure their castles against marauding neighbors. The well-knit kingdom Conan had built up seemed tottering on the edge of dissolution, and commoners and merchants trembled at the imminence of a return of the feudalistic regime. The people howled for a king to protect them against their own aristocracy no less than foreign foes. Count Trocero, left by Conan in charge of the city, tried to reassure them, but in their unreasoning terror they remembered old civil wars, and how this same count had besieged Tamar fifteen years before. It was shouted in the streets that Trocero had betrayed the king; that he planned to plunder the city. The mercenaries began looting the quarters, dragging forth screaming merchants and terrified women.

Trocero swept down on the looters, littered the streets with their corpses, drove them back into their quarter in confusion, and arrested their leaders. Still the people rushed wildly about, with brainless squawks, screaming that the count had incited the riot for his own purposes.

Prince Arpello came before the distracted council and announced himself ready to take over the government of the city until a new king could be decided upon, Conan having no son. While they debated, his agents stole subtly among the people, who snatched at a shred of royalty. The council heard the storm outside the palace windows, where the multitude roared for Arpello the Rescuer. The council surrendered.

Trocero at first refused the order to give up his baton of authority, but the people swarmed about him, hissing and howling, hurling stones and offal at his knights. Seeing the futility of a pitched battle in the streets with Arpello’s retainers, under such conditions, Trocero hurled the baton in his rival’s face, hanged the leaders of the mercenaries in the market-square as his last official act, and rode out of the southern gate at the head of his fifteen hundred steel-clad knights. The gates slammed behind him and Arpello’s suave mask fell away to reveal the grim visage of the hungry wolf.

With the mercenaries cut to pieces or hiding in their barracks, his were the only soldiers in Tamar. Sitting his war-horse in the great square, Arpello proclaimed himself king of Aquilonia, amid the clamor of the deluded multitude.

Publius the Chancellor, who opposed this move, was thrown into prison. The merchants, who had greeted the proclamation of a king with relief, now found with consternation that the new monarch’s first act was to levy a staggering tax on them. Six rich merchants, sent as a delegation of protest, were seized and their heads slashed off without ceremony. A shocked and stunned silence followed this execution. The merchants, confronted by a power they could not control with money, fell on their fat bellies and licked their oppressor’s boots.

The common people were not perturbed at the fate of the merchants, but they began to murmur when they found that the swaggering Pellian soldiery, pretending to maintain order, were as bad as Turanian bandits. Complaints of extortion, murder and rape poured in to Arpello, who had taken up his quarters in Publius’ palace, because the desperate councillors, doomed by his order, were holding the royal palace against his soldiers. He had taken possession of the pleasure-palace, however, and Conan’s girls were dragged to his quarters. The people muttered at the sight of the royal beauties writhing in the brutal hands of the iron-clad retainers—dark-eyed damsels of Poitain, slim black-haired wenches from Zamora, Zingara and Hyrkania, Brythunian girls with tousled yellow heads, all weeping with fright and shame, unused to brutality.

Night fell on a city of bewilderment and turmoil, and before midnight word spread mysteriously in the street that the Kothians had followed up their victory and were hammering at the walls of Shamar. Somebody in Tsotha’s mysterious secret-service had babbled. Fear shook the people like an earthquake, and they did not even pause to wonder at the witchcraft by which the news had been so swiftly transmitted. They stormed at Arpello’s doors, demanding that he march southward and drive the enemy back over the Tybor. He might have subtly pointed out that his force was not sufficient, and that he could not raise an army until the barons recognized his claim to the crown. But he was drunk with power, and laughed in their faces.

A young student, Athemides, mounted a column in the market, and with burning words accused Arpello of being a cats-paw for Strabonus, painting a vivid picture of existence under Kothian rule, with Arpello as satrap. Before he finished, the multitude was screaming with fear and howling with rage. Arpello sent his soldiers to arrest the youth, but the people caught him up and fled with him, deluging the pursuing retainers with stones and dead cats. A volley of crossbow quarrels routed the mob, and a charge of horsemen littered the market with bodies, but Athemides was smuggled out of the city to plead with Trocero to retake Tamar, and march to aid Shamar.

Athemides found Trocero breaking his camp outside the walls, ready to march to Poitain, in the far southwestern corner of the kingdom. To the youth’s urgent pleas he answered that he had neither the force necessary to storm Tamar, even with the aid of the mob inside, nor to face Strabonus. Besides, avaricious nobles would plunder Poitain behind his back, while he was fighting the Kothians. With the king dead, each man must protect his own. He was riding to Poitain, there to defend it as best he might against Arpello and his foreign allies.

While Athemides pleaded with Trocero, the mob still raved in the city with helpless fury. Under the great tower beside the royal palace the people swirled and milled, screaming their hate at Arpello, who stood on the turrets and laughed down at them while his archers ranged the parapets, bolts drawn and fingers on the triggers of their arbalests.

The prince of Pellia was a broad-built man of medium height, with a dark stern face. He was an intriguer, but he was also a fighter. Under his silken jupon with its gilt-braided skirts and jagged sleeves, glimmered burnished steel. His long black hair was curled and scented, and bound back with a cloth-of-silver band, but at his hip hung a broadsword the jeweled hilt of which was worn with battles and campaigns.

“Fools! Howl as you will! Conan is dead and Arpello is king!”

What if all Aquilonia were leagued against him? He had men enough to hold the mighty walls until Strabonus came up. But Aquilonia was divided against itself. Already the barons were girding themselves each to seize his neighbor’s treasure. Arpello had only the helpless mob to deal with. Strabonus would carve through the loose lines of the warring barons as a galley-ram through foam, and until his coming, Arpello had only to hold the royal capital.

“Fools! Arpello is king!”

The sun was rising over the eastern towers. Out of the crimson dawn came a flying speck that grew to a bat, then to an eagle. Then all who saw screamed in amazement, for over the walls of Tamar swooped a shape such as men knew only in half-forgotten legends, and from between its titan-wings sprang a human form as it roared over the great tower. Then with a deafening thunder of wings it was gone, and the folk blinked, wondering if they dreamed. But on the turret stood a wild barbaric figure, half naked, blood-stained, brandishing a great sword. And from the multitude rose a roar that rocked the towers, “The king! It is the king!”

Arpello stood transfixed; then with a cry he drew and leaped at Conan. With a lion-like roar the Cimmerian parried the whistling blade, then dropping his own sword, gripped the prince and heaved him high above his head by crotch and neck.

“Take your plots to hell with you!” he roared, and like a sack of salt, he hurled the prince of Pellia far out, to fall through empty space for a hundred and fifty feet. The people gave back as the body came hurtling down, to smash on the marble pave, spattering blood and brains, and lie crushed in its splintered armor, like a mangled beetle.

The archers on the tower shrank back, their nerve broken. They fled, and the beleaguered councilmen sallied from the palace and hewed into them with joyous abandon. Pellian knights and men-at-arms sought safety in the streets, and the crowd tore them to pieces. In the streets the fighting milled and eddied, plumed helmets and steel caps tossed among the tousled heads and then vanished; swords hacked madly in a heaving forest of pikes, and over all rose the roar of the mob, shouts of acclaim mingling with screams of blood-lust and howls of agony. And high above all, the naked figure of the king rocked and swayed on the dizzy battlements, mighty arms brandished, roaring with gargantuan laughter that mocked all mobs and princes, even himself.

A long bow and a strong bow, and let the sky grow dark!

The cord to the nock, the shaft to the ear, and the king of Koth for a mark!

—Song of the Bossonian Archers.

The midafternoon sun glinted on the placid waters of the Tybor, washing the southern bastions of Shamar. The haggard defenders knew that few of them would see that sun rise again. The pavilions of the besiegers dotted the plain. The people of Shamar had not been able successfully to dispute the crossing of the river, outnumbered as they were. Barges, chained together, made a bridge over which the invader poured his hordes. Strabonus had not dared march on into Aquilonia with Shamar, unsubdued, at his back. He had sent his light riders, his spahis, inland to ravage the country, and had reared up his siege engines in the plain. He had anchored a flotilla of boats, furnished him by Amalrus, in the middle of the stream, over against the river-wall. Some of these boats had been sunk by stones from the city’s ballistas, which crashed through their decks and ripped out their planking, but the rest held their places and from their bows and mast-heads, protected by mantlets, archers raked the riverward turrets. These were Shemites, born with bows in their hands, not to be matched by Aquilonian archers.

On the landward side mangonels rained boulders and tree-trunks among the defenders, shattering through roofs and crushing humans like beetles; rams pounded incessantly at the stones; sappers burrowed like moles in the earth, sinking their mines beneath the towers. The moat had been dammed at the upper end, and emptied of its water, had been filled up with boulders, earth and dead horses and men. Under the walls the mailed figures swarmed, battering at the gates, rearing up scaling-ladders, pushing storming-towers, thronged with spearmen, against the turrets.

Hope had been abandoned in the city, where a bare fifteen hundred men resisted forty thousand warriors. No word had come from the kingdom whose outpost the city was. Conan was dead, so the invaders shouted exultantly. Only the strong walls and the desperate courage of the defenders had kept them so long at bay, and that could not suffice for ever. The western wall was a mass of rubbish on which the defenders stumbled in hand-to-hand conflict with the invaders. The other walls were buckling from the mines beneath them, the towers leaning drunkenly.

Now the attackers were massing for a storm. The oliphants sounded, the steel-clad ranks drew up on the plain. The storming-towers, covered with raw bull-hides, rumbled forward. The people of Shamar saw the banners of Koth and Ophir, flying side by side, in the center, and made out, among their gleaming knights, the slim lethal figure of the golden-mailed Amalrus, and the squat black-armored form of Strabonus. And between them was a shape that made the bravest blench with horror—a lean vulture figure in a filmy robe. The pikemen moved forward, flowing over the ground like the glinting waves of a river of molten steel; the knights cantered forward, lances lifted, guidons streaming. The warriors on the walls drew a long breath, consigned their souls to Mitra, and gripped their notched and red-stained weapons.

Then without warning, a bugle-call cut the din. A drum of hoofs rose above the rumble of the approaching host. North of the plain across which the army moved, rose ranges of low hills, mounting northward and westward like giant stair-steps. Now down out of these hills, like spume blown before a storm, shot the spahis who had been laying waste the countryside, riding low and spurring hard, and behind them sun shimmered on moving ranks of steel. They moved into full view, out of the defiles—mailed horsemen, the great lion banner of Aquilonia floating over them.

From the electrified watchers on the towers a great shout rent the skies. In ecstasy warriors clashed their notched swords on their riven shields, and the people of the town, ragged beggars and rich merchants, harlots in red kirtles and dames in silks and satins, fell to their knees and cried out for joy to Mitra, tears of gratitude streaming down their faces.

Strabonus, frantically shouting orders, with Arbanus, that would wheel around the ponderous lines to meet this unexpected menace, grunted, “We still outnumber them, unless they have reserves hidden in the hills. The men on the battle-towers can mask any sorties from the city. These are Poitanians—we might have guessed Trocero would try some such mad gallantry.”

Amalrus cried out in unbelief.

“I see Trocero and his captain Prospero—but who rides between them?”

“Ishtar preserve us!” shrieked Strabonus, paling. “It is King Conan!”

“You are mad!” squalled Tsotha, starting convulsively. “Conan has been in Satha’s belly for days!” He stopped short, glaring wildly at the host which was dropping down, file by file, into the plain. He could not mistake the giant figure in black, gilt-worked armor on the great black stallion, riding beneath the billowing silken folds of the great banner. A scream of feline fury burst from Tsotha’s lips, flecking his beard with foam. For the first time in his life, Strabonus saw the wizard completely upset, and shrank from the sight.

“Here is sorcery!” screamed Tsotha, clawing madly at his beard. “How could he have escaped and reached his kingdom in time to return with an army so quickly? This is the work of Pelias, curse him! I feel his hand in this! May I be cursed for not killing him when I had the power!”

The kings gaped at the mention of a man they believed ten years dead, and panic, emanating from the leaders, shook the host. All recognized the rider on the black stallion. Tsotha felt the superstitious dread of his men, and fury made a hellish mask of his face.

“Strike home!” he screamed, brandishing his lean arms madly. “We are still the stronger! Charge and crush these dogs! We shall yet feast in the ruins of Shamar tonight! Oh, Set!” he lifted his hands and invoked the serpent-god to even Strabonus’ horror, “grant us victory and I swear I will offer up to thee five hundred virgins of Shamar, writhing in their blood!”

Meanwhile the opposing host had debouched onto the plain. With the knights came what seemed a second, irregular army on tough swift ponies. These dismounted and formed their ranks on foot—stolid Bossonian archers, and keen pikemen from Gunderland, their tawny locks blowing from under their steel caps.

It was a motley army Conan had assembled, in the wild hours following his return to his capital. He had beaten the frothing mob away from the Pellian soldiers who held the outer walls of Tamar, and impressed them into his service. He had sent a swift rider after Trocero to bring him back. With these as a nucleus of an army he had raced southward, sweeping the countryside for recruits and for mounts. Nobles of Tamar and the surrounding countryside had augmented his forces, and he had levied recruits from every village and castle along his road. Yet it was but a paltry force he had gathered to dash against the invading hosts, though of the quality of tempered steel.

Nineteen hundred armored horsemen followed him, the main bulk of which consisted of the Poitanian knights. The remnants of the mercenaries and professional soldiers in the trains of loyal noblemen made up his infantry—five thousand archers and four thousand pikemen. This host now came on in good order—first the archers, then the pikemen, behind them the knights, moving at a walk.

Over against them Arbanus ordered his lines, and the allied army moved forward like a shimmering ocean of steel. The watchers on the city walls shook to see that vast host, which overshadowed the powers of the rescuers. First marched the Shemitish archers, then the Kothian spearmen, then the mailed knights of Strabonus and Amalrus. Arbanus’ intent was obvious—to employ his footmen to sweep away the infantry of Conan, and open the way for an overpowering charge of his heavy cavalry.