Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

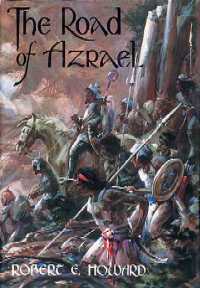

Published in The Road of Azrael, 1979, in different form under the title “The Way of the Swords.”

This version is taken from Howard’s original typescript (a few typos have been corrected).

L. Sprague de Camp edited this into the Conan story “Conan, Man of Destiny” (first published in Fantastic Universe,

December 1955), which was also published as “The Road of the Eagles” in Tales of Conan, 1955.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Though the cannon had ceased to speak, their thunder seemed still to echo hauntingly among the hills that overhung the blue water. A league from the shore the loser of that grim sea-fight wallowed in the crimson wash; just out of cannon-shot the winner limped slowly away. It was a scene common enough on the Black Sea in the year of our Lord 1595.

The ship that heeled drunkenly in the blue waste was a high beaked galley such as was used by the dread Barbary corsairs. Death had reaped a grim harvest there. Dead men sprawled on the high poop; they hung loosely over the scarred rail; they lay among the ruins of the aftercastle; they slumped along the runway that bridged the waist, where the mangled oarsmen lay among their shattered benches. Even in death these had not the appearance of men born to slavery—they were tall men, with dark hawk-like countenances. In pens about the base of the mast, fear-maddened horses fought and screamed unbearably.

Clustered on the splintered poop stood the survivors—twenty men, many of them dripping blood from wounds. The reek of burnt powder and fresh blood hung over the ship like a pall. The men were a strange picturesque band—tall and lean, most of them, as men become who spend their lives in the saddle. Indeed, they seemed not entirely at home on the water. They were burnt dark by the sun; beardless, their moustaches drooped below their chins; their heads were shaven except for a long scalp-lock on the ridge of the skull. They were clad in boots and baggy breeches of leather, nankeen or silk; some wore kalpaks, lambskin caps, others steel caps, while many had no head-wear. Some wore shirts of chain mail, others were naked to their sash-girt waists, their muscular arms and broad shoulders burnt almost black. Naked blades were in their hands—Turkish scimitars and long Hungarian sabers. Their dark eyes were restless; there was something of the eagle about them all—something wild and untamable, from the fundamental tie-ribs of Life.

They were standing about a man who lay dying on the poop. This man’s drooping moustache was shot with grey. His face was twisted with old scars. His svitka was thrown back, his shirt dyed by the blood that welled from a sword-cut in his side.

“Where is Ivan—Ivan Sablianka?” he muttered.

“Here he is, asavul,” came the chorus as a big warrior strode forward.

“Yes, here I am, uncle,” the big man twisted his moustache uncertainly. He was the tallest man there and heavily built. Clad like the others, he differed from them strangely. His wide eyes were blue as the waters of a deep sea, his scalp-lock and flowing moustache the color of spun gold. He had lost his helmet, and in his huge fist he gripped the great weapon that gave him his name—sablianka—little sword.

He bent lower to hear the words of the dying asavul.

“He has escaped us, sir brothers,” whispered this one. “Does any of the sotniks—the captains—live?”

“Nay, little uncle,” answered a lean dark warrior who was binding a rude bandage about a gashed forearm. “Tashko swallowed a bullet the wrong way, and—”

“Nay, I saw the others die,” murmured the older man. “I am the only officer among you, and I am dying. Ivan—brothers—your task is not yet done. I can not go on with you, but you must not falter. When we stood about the mangled body of Skol Ostap, our ataman, on the banks of Father Dnieper, we all swore by our Cossack honor that we would not rest until we brought back to the Sjetsch the head of the devil who slew him and our comrades. Now after we’ve followed him clear across the Black Sea in the galley we took from him, he’s beaten us off and staggers away; nay, he can not ride far on a horse we foundered with cannon balls. He’ll run in to shore. You have horses—follow! To Stamboul or to hell if you must! Ivan, you are essaul—sergeant—now. Follow! Die or take the head of Osman Pasha—who—slew—Skol—Ostap—”

The shaven head dropped on the scarred breast. The Cossacks shifted and murmured in their moustaches. They looked expectantly at Ivan Sablianka. He gnawed his moustache reflectively, glanced at the lateen sail drooping in the windless air, and stared at the shoreline. Besides that of their foe, no other sail was visible on the sea, no harbor or town on that wild lonely coast. Low, tree-covered hills rose from the waterline, climbing swiftly to blue mountains in the distance, on whose snow-tipped peaks the sinking sun flamed red. There was a reason why Ivan should know more about seas and ships than his comrades, but he had no exact idea as to where they were. They had crossed the Black Sea; therefore they were now in Moslem territory; these hills were doubtless full of Turks—in his mind he lumped all Muhammadan races under a single contemptuous term.

Under a broad shading hand he stared at the slowly receding craft—a counterpart to that on which he stood. Its crew had been glad enough to break away from the death-grapple. Ivan knew that it was crippled beyond repair, though in better shape than the bulk which was sinking under his feet. The corsair was making for a creek which wound out of the hills between high cliffs. She moved slowly, heeling to port, but Ivan believed she would make it. On the poop he could still make out a figure which caused him to rumble in his throat—a tall figure, on whose mail and helmet the sinking sun sparkled. Ivan remembered the features under that helmet, glimpsed in the chaotic frenzy of battle—hawk-nosed, grey-eyed, black-bearded—stirring in the Cossack an illusive sensation of semi-recollection. That was Osman Pasha, until recently the scourge of the Levant, most renowned of all the Algerian corsairs.

Ivan studied the shoreline. He could not follow to the creek-mouth, but he believed he could run the galley ashore on a sloping headland that ran out from the hills nearer at hand.

He went to one of the steering-sweeps. “Togrukh and Yermak take the other,” he directed; “Demetri and Konstantine quiet the horses. The rest of you dog-brothers tie up your cuts and then go down into the waist and do the best you can at rowing. If any of those Algerian pigs are still alive, knock ’em on the head.”

There were not. Those the cannon balls of their former comrades had spared, had been mowed down by the pistols and swords of the Cossacks as they broke their chains and strove to swarm up out of the waist.

Slowly and laboriously they worked the galley inshore. The sun was setting, the long shadows of the cliffs turning from dark blue to velvety purple. A haze like soft blue smoke hovered over the dark water that sunset turned to dusky amethyst. A few stars blinked out in the east. The corsair galley had limped into the mouth of the creek, vanishing between the towering cliffs.

Ivan and his comrades worked stolidly. The starboard rail was almost awash, and the Cossacks abandoned the oars and came up on the poop. The horses were screaming again, mad with fear at the rising water. The Cossacks looked at the shore, teeming, for all they knew, with hostile tribes, but they said nothing. They followed Ivan’s directions as implicitly as if he had been elected ataman by regular conclave in the Sjetsch, that stronghold of free men on the lower reaches of the Dnieper.

It was the only real democracy that ever existed on earth; a democracy where there was no class distinction save that of personal prowess and courage. To the Saporoska Sjetsch came men of all lands and races, leaving their pasts behind, to merge into the new race that was there being evolved. They took new names, entered into new lives. None asked their real names, nor whence they came. They were of many bloods. Togrukh, for example, was the son of a renegade Hungarian colonel and a Tatar slave-woman.

Whence Ivan came, none knew or cared. He had wandered into the Sjetsch five years before, speaking brokenly the speech of the Muscovites. He had aroused some suspicion at the beginning. He affirmed that he believed in God—which was one of the few questions asked an applicant to the Sjetsch—but he was reluctant to cross himself. After argument he compromised by cutting a cross in the air with his sword. He was narrowly watched for some time, but soon proved his honesty in battles against the Turks, and the Tatars of Crimea. Whatever his former life and tongue, he was all Cossack now. He might have been born and raised on the southern steppes.

His sword was one departure from form, among men where curved blades were almost universally the rule. It was straight, four and a half feet in length from point to pommel, broad, double-edged, a blade for thrusting as well as hacking. Not much inferior in weight to the five-foot two-handed swords used by the Wallachian and German men-at-arms, it was meant to be wielded with one hand. From the wide crosspiece to the heavy silver ball that was the pommel, curved a broad hand-guard in flaring lines of gilt-chased iron. Not half a dozen men on the frontier could wield that sword with one hand. It was in Ivan’s fingers now as he leaned on the useless sweep and stared at the headland which loomed nearer and nearer with each heave and roll of the floundering galley.

In the fertile valley of Ekrem happenings were coming to pass. The river that wound through the small patches of meadowland and farmland was tinged red, and the mountains that rose on either hand looked down on a scene only less old than they. Horror had come upon the peaceful valley-dwellers, in the shape of lean wolfish riders from the outlands. They did not turn their gaze toward the castle that hung as if poised on the sheer slope high up the mountains; there too lurked oppressors.

The clan of Ilbars Khan, the Turkoman, driven westward out of Persia by tribal feud, was taking toll among the Armenian villages in the valley of Ekrem. It was but a raid among raids, for cattle, slaves and plunder, meant to impress his lordship over the caphar dogs. He was ambitious; his dreams embraced more than the leadership of a wandering tribe. Chiefs had carved kingdoms out of these hills before.

But just now, like his warriors, he was drunk with slaughter. The huts of the Armenians lay in smoking ruins. The barns had been spared, because they contained fodder for horses, as well as the ricks. Up and down the valley the lean riders raced, stabbing and loosing their arrows. Men screamed as the steel drove home; women shrieked as they were jerked naked across the raiders’ saddle-bows.

The horsemen in their sheepskins and high fur kalpaks were swarming in the straggling streets of the largest village—a squalid cluster of huts, half mud, half stone. Routed out of their pitiful hiding-places, the villagers knelt vainly imploring mercy, or as vainly fled, to be ridden down as they ran.

Foremost in this sport was Ilbars Khan, and lost the chance of a kingdom thereby. He spurred between the huts, out into the meadow, chasing a ragged wretch whose heels were winged by the fear of death. Ilbars Khan’s lance-point caught him between the shoulder-blades. The spear-shaft snapped and the drumming hoofs spurned the writhing body as the chief swept past.

“Allah il allah!” Beards were whitened with foam at the blood-mad cry.

The yataghans whistled, ending in the zhukk! of cloven flesh and bone. With a wild cry a fugitive turned as Ilbars Khan swooped down on him, his wide kaftan spreading out in the wind like the wings of a hawk. In that instant the dilated eyes of the Armenian saw, as in a dream, the lean bearded face with its thin down-curving nose; the gold-broidered vest beneath the flowing cloak, crossed by the wide silk girdle from which projected the ivory hilts of half a dozen daggers; the wide sleeve falling away from the lean muscular arm that lifted ending in a broad curving glitter of steel. In that instant too the Turkoman saw the lean stooped figure tensed beneath the rags, the wild eyes glaring from under the lank tangle of hair, the long glimmer of light glancing along the barrel of a musket. A wild cry rang from the lips of the hunted, drowned in the bursting roar of the firelock. A swirling cloud of smoke enveloped the figures, in which a flashing ray of steel cut the murk like a flicker of lightning. Out of the cloud raced a riderless steed, reins flowing free. A breath of wind blew the smoke away.

One of the figures on the ground was still writhing; slowly it drew itself up on one elbow. It was the Armenian, life welling fast from a ghastly cut across the neck and shoulder. Gasping, fighting hard for life, he looked down with wildly glaring eyes on the other form. The Turkoman’s kalpak lay yards away, blown there by the close-range shot; most of his brains were in it. Ilbars Khan’s beards jutted upward, as if in ghastly comic surprise. The Armenian’s arm gave way and his face crashed into the dirt, filling his mouth with dust. He spat it out, dyed red. A ghastly laugh slobbered from his frothy lips. It rose to a shout that scared the wheeling vultures. He fell back thrashing the sand with his hands, yelling with maniacal mirth. When the horrified Turkomans reached the spot, the Armenian was dead with a ghastly smile frozen on his lips. He had recognized his victim.

The Turkomans squatted about like evil-eyed vultures about a dead sheep, and conversed over the body of their khan. Their speech was evil as their countenances, and when they rose from that buzzards’ conclave, the doom had been sealed of every Armenian in the valley of Ekrem.

Granaries, ricks and stables, spared by Ilbars Khan, went up in flames. All the prisoners taken were slain—infants tossed living into the flames, young girls ripped up and flung into the blood-stained streets. Beside the Khan’s corpse grew a heap of severed heads; the riders galloped up, swinging the ghastly relics by the hair, tossing them on the grim pyramid. Every place that might conceivably lend concealment to a shuddering wretch was ripped apart.

It was while engaged in this, that one of the tribesmen, prodding into a stack of hay, discerned a movement in the straw. With a wolfish yell he pounced upon it, and dragged his victim to light, giving tongue in lustful exultation as he saw his prisoner. It was a girl, and no stodgy Armenian woman, either. Tearing off the cloak which she sought to huddle about her slender form, he feasted his vulture-eyes on her beauty, scantily covered by the garb of a Persian dancing-girl. Over her filmy yasmaq—her light veil—her dark eyes, shadowed by long kohl-tinted lashes, were eloquent with fear.

She said nothing, struggling fiercely, her lithe limbs writhing in his cruel grip. He dragged her toward his horse; then quick and deadly as a striking cobra, she snatched a curved dagger from his girdle and sank it to the hilt under his heart. With a groan he crumpled, his sheepskins dyed red, and she sprang like a she-panther to his horse, seeming to soar to the high-peaked saddle, so lithe were her motions. The tall steed neighed and reared, and she wrenched it about and raced up the valley. Behind her the pack gave tongue and streamed out in hot pursuit. Arrows whistled about her head, and she flinched as they sang venomously by, but urged the steed to more frenzied efforts.

She reined him straight at the mountain wall on the south, where a narrow canyon opened into the valley. Here the going was perilous, and the Turkomans reined to a less headlong pace among the rolling stones and broken boulders. But the girl rode like a leaf blown before a storm, and so it was that she was leading them by several hundred yards when she came upon a cluster of tamarisk-grown boulders that rose island-like above the level of the canyon floor. There was a spring among those boulders, and men were there.

She saw them among the rocks, and they shouted at her to halt. At first she thought them Turkomans; then she saw otherwise. They were tall and strongly built, chain mail glinting under their cloaks. Their white turban-cloths were wrapped about steel caps that rose to a spire-like peak. Their dark faces were strong and reckless. If the Turkomans were jackals, these were hawks. All this she saw in that moment, her quick perception abnormally whetted by desperation. She saw too the muzzles of matchlocks among the rocks, and caught the flicker of burning fuses. And she made up her mind instantly. Throwing herself from the steed, she ran up the rocks, falling on her knees.

“Aid, in the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate!”

A man emerged from a clump of bushes and looked down at her. And as she looked, she cried out again incredulously.

“Osman Pasha!” Then recollecting her urgent need, she clasped his knees, crying “Yah khawand, protect me! Save me from these wolves who follow!”

“Why should I risk my life for you?” he asked indifferently.

“I knew you of old in the court of the Padishah!” she cried desperately, tearing off her veil. “I danced before you. I am Ayesha—”

“Many women have danced before me,” he answered. “I have no quarrel with these desert-dogs.”

“Then I will give you a talsmin,” said she in final desperation. “Listen!”

And as she whispered a name in his ear, he started as if stung. Quickly he raised his head, staring at her as if to plumb the depths of her inmost mind. For an instant he stood motionless, his grey eyes turned inward, then clambering up a great boulder, he faced the oncoming riders with lifted hand.

“Go your way in peace, in the name of Allah!”

His answer was a whistle of arrows about his ears. He sprang down, waving his hand. Instantly matchlocks began to crash from among the rocks, the smoke billowing about the thicket-clad knoll. A dozen wild riders rolled from their saddles and lay twitching. The rest gave back, yelling in dismay. They wheeled about and cantered swiftly back up the gorge toward the main valley.

Osman Pasha turned to Ayesha, who had modestly resumed her veil. He was a tall man, with grey eyes like ice and steel. There was in his manner a certain ruthless directness rare in an Oriental. His cloak was of crimson silk, his corselet of close-meshed chain mail threaded with gold. His green turban was held in place by a jeweled brooch, and his spired helmet was chased in silver. Ivory butts of gold-mounted pistols jutted from his shagreen girdle, which was resplendent with a great golden buckle, and his boots were of finest Spanish leather. Salt water, powder smoke and blood had stained and tarnished his apparel; yet the richness of his garments and weapons was notable, even in that age of lavish accouterments.

His men were gathered about him, forty Algerian pirates, as ruthless and courageous a race as ever trod a deck, bristling with firearms and scimitars. In a depression behind the knoll were horses of a rather inferior breed.

“My daughter,” said Osman Pasha in a benignant manner that was belied by his cruel eyes, “I have made enemies in this strange land, and fought a skirmish on your behalf, because of a name whispered in my ear. I believed you—”

“If I lied may my hide be stripped from me,” she swore.

“It will be,” he promised gently. “I will see to it personally. You spoke the name of Prince Orkhan. What do you know of him?”

“For three years I have shared his exile.”

“Where is he now?”

She pointed up toward the mountains that overhung the distant valley, where the turrets of the castle were just visible among the crags.

“Across the valley, in yonder castle of El Afdal Skirkuh, the Kurd.”

“It would be hard to take,” he mused.

“Send for the rest of your sea-hawks!” she cried. “I know a way to bring you to the very heart of that keep!”

He shook his head.

“These ye see are all my band.”

Then seeing her incredulous glance, he said, “I am not surprised that you wonder at my change of fortune. I will tell you—”

And with the disconcerting frankness of the man, which his fellow Moslems found so inexplicable, Osman Pasha briefly sketched his fall. He did not tell her of his triumphs; they were too well known to need repeating. Five years before he had appeared suddenly on the stage of the Mediterranean, as a reis of the famed corsair, Seyf ed-din Ghazi. He soon outstripped his master and gathered a fleet of his own, which owned allegiance to no ruler, not even the Barbary beys. At first an ally of the Grand Turk and a welcome guest at the Sublime Porte, he had later enraged the Sultan by his raids on Turkish shipping.

A deadly feud had arisen between them, and at last fate had declared in favor of Murad. Pillaging along the Dardanelles, the corsair had been trapped by an Ottoman fleet and all his ships destroyed except two. But the Sultan had spared his life, giving him a task that practically amounted to a death sentence. He was commanded to sail up the Black Sea to the Dnieper mouth and there destroy another foe of the Turk’s—Skol Ostap, the Koshevoi Ataman of the Zaporogian Cossacks, whose raids into Turkish dominions had driven the Sultan well-nigh to madness.

The Cossacks at intervals shifted their Sjetsch—their armed camp—from island to island, secretly, to avoid surprise attacks, but Osman’s luck had been with him to a certain extent. A Greek traitor had led him to the Dnieper island then occupied by the free warriors, and at a time when many of them were away on a raid against the Tatars across the river. The flying raid had failed in capturing Skol Ostap, lying helpless of an old wound, because of the ferocious resistance of the Cossacks with him. In the midst of the battle the riders had returned from pounding the Tatars, and Osman fled, leaving one of his ships in their hands. He knew the penalty for failure, and instead of fleeing toward the Turkish fleet which waited down along the coast, he struck straight out across the Black Sea, soon pursued by the Cossacks in his captured ship, using its crew for oarsmen. He did not understand the ferocity of their pursuit, not knowing that a bursting shell from his cannon had slain the wounded Skol Ostap and maddened his kunaks thereby.

When the eastern coast was in sight, the reckless Cossacks had drawn up within cannon-shot, and in the ensuing battle only the rising of the oarsmen on their craft had won the day for the corsair.

“So we ran the galley ashore in the creek. We might have repaired her, but whither go? The Sultan’s fleets hold the gateway out of the Black Sea, and he will have a bowstring ready for me when he knows I’ve failed. We found a village up along the creek—Moslems of a sort who toiled among vineyards and the fishing nets. There we procured horses and struck through the mountains, seeking we know not what—a way out of Ottoman dominions, or a new kingdom to rule. Who knows?”

They had pushed on through the mountains for days, preferring the wild desolation of uninhabited land to the risk of falling afoul of Turkish outposts. Osman Pasha had an idea that already swift couriers had carried the word throughout the empire that he was doomed. Whatever else the Turkish sultans were or were not, they were thorough in their vengeance. He had been wandering without a plan, trusting to his luck. The fatalism of the Turk was not his.

Ayesha listened, and without comment began her tale. As Osman well knew, it was the custom of the sultans, upon coming to the throne, to butcher their brothers and their brothers’ children. Bayazid i began that custom, and whatever its moral aspects, it can not be denied that it saved the empire from many disastrous civil wars—each Ottoman prince considering the throne his prerogative. Sometimes a prison took the place of the bowstring, as in the case of prince Jem, brother of Bayazid ii, who was the unwilling guest for many years, first of the Knights of St. John on Rhodes, to whom the Sultan paid 45,000 ducats a year as gaoler’s fee, and later of two successive popes, the last of whom, Alexandria Borgia, considerately poisoned the unhappy prince in return for a lump sum of gold from the Sultan.

This precedent was followed later, as with prince Orkhan, son of Selim the Drunkard, and brother of Murad iii. A curious parallel might be noted here. Just as in the case of Jem and Bayazid, when the weaker brother won over the stronger by force of circumstances, so in the later case. When Selim the Drunkard passed out of his besotted life, Orkhan was in Egypt. Murad was in Skutari. In the resultant race for the capital, the result is obvious. It had long been a custom among the Turks to grant the crown to whichever heir first reached Constantinople after the death of the Sultan. The viziers and beys, dreading civil war, generally supported the first comer, who in turn bought the janizaries with rich gifts, and with their aid set about eliminating his brothers. Even with this advantage the weak Murad could never have resisted his more aggressive brother, had it not been for his harim favorite, Safia, a Venetian woman of the Baffo family. She was the real ruler of Turkey, and by her wiles, whereby the Venetians were drawn in to aid the Sultan, Orkhan’s thrust for the throne was defeated and he went into exile.

At first he had sought refuge in the Persian court, and the Shah had promised him aid in gaining the crown. But a few brushes with the dread janizaries cooled the Persian ardor, and Orkhan discovered that the Shah was corresponding with Safia in regard to poisoning him. He made his escape, but in attempting to reach India, was taken captive by the nomadic Bashkirs, who recognized him and sold him into the hands of the Ottomans. Orkhan considered his fate sealed but Murad dared not have him butchered, for he was still very popular with the masses, especially the subject but ever turbulent Memluks of Egypt, and the Sipahis, or independent landholders of Anatolia. He was confined in a castle near Erzeroum, and furnished with all luxuries and forms of dissipation calculated to soften his fibre.

This was being gradually brought about, Ayesha said. She was one of the dancing-girls sent to entertain him. She had fallen violently in love with the handsome prince, and instead of seeking to ruin him with her passion and amorous wiles, had labored to lift him back to manhood. She had succeeded so well—though without being suspected as the prime motive force—that the prince had been hurriedly and secretly taken from Erzeroum and carried up into the wild mountains above Ekrem, there to be put in charge of El Afdal Shirkuh, a fierce semi-bandit chief, whose family had reigned as feudal lords over the valley for a generation or so, preying on the inhabitants, though not protecting them.

“There we have been for more than a year,” concluded Ayesha. “Prince Orkhan has sunk into apathy. One would not recognize him for the young eagle who led his Egyptian horsemen into the teeth of the janizaries. Imprisonment and bhang and wine have drugged his senses. He sits on his cushions in kaif, rousing only when I sing or dance for him. But he has the blood of conquerors in him. His grandfather, Suleyman the Magnificent, is reborn in him. He is a lion who but sleeps—

“When the Turkomans rode into the valley, I slipped out of the castle and came looking for their chief, Ilbars Khan, for I had heard of his prowess and ambitions. I wished to find a man bold enough to free Orkhan. Let the young eagle’s wings feel the wind again, and he will rise and shake the dust from his brain. Again he will be Orkhan the Splendid. I sought Ilbars Khan, but I saw him slain before I could reach him, and then the Turkomans were like mad dogs. I was afraid and hid, but they dragged me out.

“Oh, my Lord, aid us! What if you have no ship and only a handful at your back? Kingdoms have been built on less! When it is known that the prince is free—and thou art with him!—men will flock to us! The feudal lords, the Timariotes, they supported him before, and will not turn from him now. Nay, had they known the place of his confinement, they had torn yon keep stone from stone already! The Sultan is besotted. The people hate Safia and her mongrel son Muhammad.

“The nearest Turkish post is three days’ ride from this place. The valley of Ekrem is isolated, unknown to most except wandering Kurds and the wretched Armenians. Here an empire can be plotted unmolested. You, too, are an outlaw. Let us band together. We will free Orkhan—place him on his rightful throne! If Orkhan were Padishah, all wealth and power and honor were yours; Murad offers you naught but a bowstring!”

She was on her knees before him, her white fingers convulsively gripping his cloak, her veil torn aside again, her dark eyes blazing with the passion of her plea. Osman Pasha was silent, but cold lights glimmered in his steely eyes. He knew that what the girl said of Orkhan’s popularity was true; nor did he underrate his own power. King-maker! It was such a role as he had dreamed of. And this desperate adventure, with death or a throne for prize was just such as to stir his wild soul to the utmost. Suddenly he laughed, and whatever crimes stained the man’s soul, his laugh was as ringing and zestful as a gust of sea-wind, rising strange from a Moslem’s lips.

“We’ll need the Turkomans in this venture,” he said, and the girl clapped her hands with a brief passionate cry of joy, knowing she had won her plea.

“Hold up, kunaks!” Ivan Sablianka pulled up his steed and glanced about, craning his thick neck forward. Behind him his comrades shifted in their saddles. They were in a narrow canyon, flanked on either hand by steep slopes, grown with bushes and stunted firs. Before them a small spring welled up in the midst of straggling trees, and trickled away down a narrow moss-green channel.

“Water here, at least,” grunted Ivan. “The nags are tired. Light.”

Without a word the Cossacks dismounted, drew off the saddles, and allowed the weary horses to drink their fill, before they satisfied their own thirst. For days they had followed the trail of the wandering Algerians. Since leaving the coast and the village along the creek, they had seen only one sign of life: a huddle of mud-huts perched up high among the crags, housing nondescript skin-clad creatures who fled howling into the ravines at their approach. They had been thoroughly looted by the Algerians, so that the Cossacks had been hard put to it to scrape together feed for the horses. For the men there was no food. But the Cossacks had been hungry before.

The provisions with which they had filled their saddle-bags before leaving the village on the creek, were exhausted. The Algerians had taken heavy toll of its store-houses and granaries, and the Cossacks, coming after, had stripped them. There was little grass in those mountains for grazing. Now the Cossacks were without food, and they had lost the trail of the corsairs.

The previous nightfall had found them rapidly overhauling their prey, as shown by the freshness of the spoor, and they had recklessly pushed on, thinking to come upon the Algerian camp in the night. But with the setting of the young moon, they had lost the trail in a maze of gullies and crags, and had wandered blindly and at random. Now at dawn they had found water, but their horses were worn out, and they themselves completely lost. This would never have occurred had they been led by a real sotnik or essaul. But they had no word of blame for Ivan, whose thoughtless recklessness had gotten them into their present situation.

“Get some sleep,” growled Ivan. “Togrukh, you and Stefan and Vladimir take the first watch. When the sun’s over that fir tree, wake three others to watch. I’m going to scout a bit up this gorge.”

He strode away up the canyon soon lost among the straggling growth. Soon the way tilted upward, and the slopes on either hand changed to towering cliffs that rose sheer from the rock-littered floor. And with heart-stopping suddenness, from a tangle of bushes and broken boulders, a wild shaggy figure sprang up and confronted the Cossack. Ivan’s breath hissed through his teeth as his sword glittered high in the air; then he checked the stroke, seeing that the apparition was weaponless. It was a lean gnome-like man in sheepskins. His eyes, glaring wildly from a tangle of lank hair, took in every detail of the giant Cossack, from his scalp-lock to his silver-heeled boots. They took in the stained mail shirt tucked into his wide nankeen breeches, the pistol butts jutting from his broad silken girdle, the sword in his huge hand.

“God of my fathers!” said the vagabond in the speech of the Cossacks. “What does one of the free brotherhood in this Turk-haunted land?”

“Who are you?” grunted Ivan warily.

“A man who has just seen his people slaughtered,” answered the other with a wild laugh of mad despair. “I was the son of a kral of the Armenians—call me Kral. One name is good as another to an outcast. What do you here?”

“What lies beyond this canyon?” asked Ivan, instead of answering.

“Over yonder ridge which closes the lower end of this defile lies a tangle of gulches and crags. If you thread your way among them, you will come out overlooking the broad valley of Ekrem which until yesterday was the home of my tribe, and which today holds their charred bones.”

“Is there food there?”

“Aye—and death. A horde of Turkomans hold the valley.”

As Ivan meditated this, a quick step brought him about, to see Togrukh approaching.

“Hai!” Ivan scowled. “You had an order to watch while the kunaks slept!”

“The kunaks are too cursed hungry to sleep,” retorted the saturnine Cossack eyeing the Armenian suspiciously.

“Devil bite you, Togrukh,” growled the big warrior, “I can’t conjure them mutton out of the air. They must gnaw their thumbs until we find a village to loot—”

“I can lead you to enough food to feed a regiment,” interrupted Kral.

“Don’t mock me, Ermenie,” scowled Ivan; “you just said the Turkomans—”

“Nay,” cried Kral, “there is a place not far from here, unknown to the Moslems, where my people stored food secretly. Thither I was going when I saw you coming up the gorge and knew you for a Kazak.”

Togrukh looked at Ivan, who drew a pistol and cocked it.

“Then lead on, Kral,” said the Zaporogian, “but at the first false move—bang! goes a ball through your head.”

The Armenian laughed, a wild scornful laugh, and motioned for them to follow. He made straight toward the nearer cliff, and groping among a cluster of brittle bushes, disclosed what looked like a shallow crack in the wall. Beckoning them after him, he bent and crawled inside.

“Into that wolf’s den?” Togrukh glared suspiciously, but Ivan followed the Armenian, and the other came after him. They found themselves in, not a cave, but a narrow cleft of the cliff, in breathless twilight gloom. Ivan swore and grunted as he levered his huge bulk between the shouldering walls, but within a few paces it widened until the giant could walk with ease. Forty paces further they came out into a wide circular space, surrounded by towering walls that resembled monstrous honeycombs.

“These were the tombs of an ancient, unknown people who held this land before the coming of my ancestors,” said Kral. “Their bones have long turned to dust. The caves were empty, and there my people stored food against times of famine and pillage. Take your fill; there are no Armenians to need it.”

Ivan looked curiously about him. It was like being at the bottom of a giant well. The floor was solid rock, worn smooth and level, as if by the feet of ten thousand generations. The walls, honeycombed with regular tiers of tombs for fifty feet on all sides, rose stupendously, ending in a small circle of blue sky. A vulture hung in the blue disk like a tiny black dot.

“Your people should have dwelt here in these caves,” said Togrukh. “Then when the Turks came—cut, slash! One man could hold that outer cleft against a horde.”

The Armenian shrugged his shoulders. “Here there is no water. When the Turkomans swooped down there was not time to run and hide. My people were not warlike. They only wished to till the soil.”

Togrukh shook his head, unable to understand such natures. Kral was pulling food for man and beast out of the lower caves—leather bags of grain, rice, moldy cheese, and dried meat, skins of sour wine.

“Go get some of the lads to help carry the stuff, kunak,” directed Ivan, bending his massive back toward his heels to gaze up at the higher caves. “I’ll stay here with Kral.”

Togrukh swaggered off, his silver heels rapping on the stone, and Kral tugged at Ivan’s steel-clad arm.

“Now do you believe I am a true man, effendi?”

“Aye, by God,” Ivan answered, gnawing a handful of dried figs. “Any man that leads me to food is a friend of mine. But where were the villages of these ancients? They couldn’t raise grain in that rocky canyon outside.”

“They dwelt in the valley of Ekrem. Long, long ago my ancestors came out of the north and found them tilling the soil there, and took their land.”

“Well,” grunted Ivan, “that’s the way it goes. Now the Turks are slaughtering you fellows. But don’t worry; some day we Cossacks will ride over the mountains and cut their throats. Slash, bang! that’s the way it’ll be. But if the old people dwelt in the valley, why didn’t they lay away their dead closer by? It must be a long steep road from here to Ekrem.”

Kral’s eyes gleamed like a hungry wolf’s. “That is the secret locked in the heart of these hills, known only to my people. But I will show you—and more, if you will trust me.”

“Well, Kral,” said Ivan, munching away with relish, “we Zaporogians have no need to lie and hide like a Jew. We’re following that black devil Osman Pasha the corsair, who’s somewhere in these mountains—”

“Osman Pasha is no more than three hours’ ride from this spot.”

“Ha!” Ivan dashed down the food he was munching, and caught at his sword, his blue eyes ablaze.

“Kubadar—take care!” cried Kral. “There are forty corsairs, armed with matchlocks and entrenched among the boulders of Diva gorge. And they have been joined by Arap Ali and his hundred and fifty Turkomans. How many warriors have you, effendi?”

Ivan twisted his flowing moustache without reply, scowling heavily. He scratched his head, wondering what an ataman would have done under these circumstances. Deep thinking always made him drowsy and he detested the effort. His head swam and his heavy arms ached with the desire to draw his great sword and forget the weariness of meditation in the dealing of gigantic strokes. It was significant that though he was the foremost swordsman of the Sjetsch, he had never before been given the leadership of his comrades. He swore now at the necessity. He was wiser than his kunaks, but he frankly admitted that was no great evidence of wisdom. Like them, he was utterly reckless and improvident. Well led, they were invincible. Without wise leadership they would throw their lives away on a whim. He had made a mistake pushing on after dark, last night, but that fact had probably not occurred to any of them. Kral watched him keenly, reading the big Cossack’s mental workings from the expressions of his broad bluff face.

“Osman Pasha is your enemy?”

“Enemy!” Ivan repeated aggrievedly. “I’ll line my saddle with his hide—”

“Pekki! Then come with me, Kazak, and I will show you what no man save an Armenian has seen for a thousand years.”

“What’s that?” demanded Ivan suspiciously.

“A secret way—and a road of death for our enemies!”

Ivan took a step forward, then halted.“Wait. Here come the sir brothers. Listen to them swear, the dogs.”

“Send them back into the canyon with the food,” whispered Kral, as half a dozen scalp-locked warriors swaggered out of the cleft and gaped curiously around. Ivan faced them portentously, booted legs wide-straddled, belly thrust out, thumbs hooked into his girdle.

“Take up this stuff and lug it back to the spring, kunaks,” he said with a grand gesture. “I told you I’d find food for you and the nags.”

“And what of you?” queried Togrukh, who was bitten by the devil of curiosity as he gnawed a strip of pasderma—sun-dried mutton.

“Don’t fret about me,” roared Ivan. “Am I not the essaul? I have words with Kral. Go back to camp and eat beans, devil bite you!”

After the clatter of their boot-heels had faded down the cleft, Kral led the way to the opposite wall and showed Ivan a series of steps carved in the rock. Up these he went like a cat, while the Zaporogian followed more slowly, suspicious of the hand-holds. High above the last tier of tombs the dim ladder ended at the mouth of a cavern much larger than the others; in it Ivan could stand upright. He saw that, instead of being a mere niche in the cliff like the others, this cave ran back and disappeared in darkness.

“Up this shaft came the ancients bearing their dead,” said Kral. “It leads to the vale of Ekrem. Once another shaft led down from tier to tier to the floor of this place, but that has been long choked with the falling in of the walls. If you follow this tunnel, you will come out behind the castle of the Kurd, El Afdal Shirkuh, that overlooks Ekrem.”

“How shall it profit us?” grunted Ivan.

“Listen, and I will tell you a tale!” exclaimed Kral, squatting in the semi-darkness, his back against the cave-wall. “Yesterday when the slaughtering began, I strove for awhile with the Turki dogs; then when my comrades had been cut down, I fled, and leaving the valley, ran down the gorge of Diva. In the midst of this gorge there is a great heap of boulders, masked by thickets. I sought refuge there, only to find it occupied by a strange band of warriors. I was among them before I was aware of them, and they beat me down with the barrels of their pistols, and bound me, asking me questions as to what went on in the valley; for as they rode down the gorge, they had heard the shots and shouting, and had halted and entrenched themselves on the knoll, and were about to send scouts forward. They were Algerian pirates and they called their emir Osman Pasha.

“While they questioned me, a girl came riding like one mad, with the Turkoman at her heels. When she sprang from her horse and begged aid of Osman Pasha I recognized her as the Persian dancing-girl who dwells in the castle. He and his men scattered the Turkomans with a volley from their matchlocks, and then he talked with the girl, Ayesha. They had forgotten me and I lay near, bound, and heard all they said.

“For more than a year, Shirkuh has held a captive in his castle. I know, because I have taken grain and sheep to the castle, to be paid for after the Kurdish fashion, with curses and blows. Kazak, the prisoner is Orkhan, brother of Murad Padishah!”

The Cossack grunted in surprize.

“This Ayesha disclosed to Osman, and he swore to aid her in freeing the prince. As they talked the Turkomans returned in full force and reined in at a distance, wishful to attack, yet fearing the matchlocks. Osman hailed them, and they had speech, he and their chief Arap Ali who commands since their khan was slain, and at last the Turkoman came among the rocks and squatted at Osman’s fire and shared bread and salt. And the three plotted to rescue Prince Orkhan, and put him on the Ottoman throne.

“Ayesha had discovered the secret way from the castle. This day, just before sunset, the Turkomans are to attack the castle openly, and while they thus attract the attention of the Kurds, Osman and his Algerians are to come to the castle by the secret way. Ayesha will have returned to Orkhan, and will open the secret door for them. They will take the prince away, and ride into the hills, recruiting warriors. As they talked night fell, and I gnawed through my cords and slipped away.

“You wish vengeance—here is a chance for both vengeance and profit, yah kahwand! I will show you how to trap Osman. Slay him—slay the girl—and their followers—take Orkhan and wring a mighty price from Safia. She will pay you richly to keep him out of the way, or to slay him.”

“Show me,” grunted the Cossack incredulousy. Kral nodded. Groping into a pile of goods in a corner, he produced a torch, which he lighted with flint and steel. Then beckoning Ivan, he started off down the cavern. The Zaporogian drew his broadsword and followed.

“No tricks, Kral,” he cautioned, “or your head leaves your shoulders.”

The Armenian’s laugh rang savagely bitter in the gloom. “Would I betray Christians to the butchers of my people? Through you I may have vengeance. Therefore trust me.”

Ivan made no reply, and Kral led the way through a narrow doorway and into a tunnel beyond. Here the vaulted roof was higher than a man could reach, and three horses might have been ridden abreast. The smooth rock floor slanted slightly downward, and from time to time they came to short flights of steps cut into the stone, giving onto lower levels. Ivan twisted his moustache reflectively and stared about him. The flickering torchlight shone on figures carved all along the walls in bas-relief. They were mostly shapes of men, short, thick-bodied, with round heads and broad noses. They made war on one another, hunted lions, brought gifts to a fantastic anthropomorphic figure that must have been a god, and in some of the carvings fought men of an unmistakably different race, taller and more symmetrically shaped men, with long beards and hook noses. Ivan detected a faint resemblance between these figures and Kral.

As they progressed, the Cossack seemed to hear a murmur of running water from time to time. He mentioned this.

“We have left the tunnel the old ones made,” answered Kral. “We are in an old water-course now. Once a stream ran through here, cutting through the solid rock. For some reason it changed its course, God only knows how many thousands of years ago. It is that you hear, flowing through the darkness not far away, but through another channel. Soon you will see it. It has its head far up among the mountains, but is mainly subterranean.”

Presently Ivan heard the unmistakable ripple of falling water, and ahead of him the tunnel ended abruptly in what appeared to be a solid rock wall. But it was too smooth and symmetrical to be the work of nature; it was a huge block of stone, shaped by the hand of man, and about the edges stole a thin grey light. Extinguishing the torch, Kral fumbled in the darkness, and Ivan heard him strain and grunt in the darkness. The block, hung on a stone pivot, swung aside and a sheet of silver shimmered before the Cossack’s eyes.

They stood in the narrow mouth of the tunnel, which was masked by a sheet of water rushing over the cliff high above. At the foot of the falls a circular pool foamed and eddied, and from it a narrow stream raced away down the gorge. Kral pointed out a ledge that ran from the mouth of the cavern, skirting the edge of the pool, and Ivan followed him, first wrapping his powder-flask and pistol-locks carefully in his silken sash. At the edge, the falling water formed such a thin sheet that neither man was completely soaked in gaining the outer world. Ivan saw that he was in a narrow gorge that was like a knife-cut through the hills. Nowhere was it more than forty or fifty paces wide, and on either hand sheer cliffs towered for hundreds of feet, higher on the left than on the right. No vegetation grew anywhere, except for a fringe about the edge of the pool, and along the course of the narrow stream. This stream meanderingly crossed the canyon floor to plunge into a narrow crack in the opposite cliff—eventually to find its way into the river that traversed Ekrem, Kral said. Ivan glanced back the way they had come; the falling water completely masked the tunnel-mouth. Even with the door-block pulled aside, he could have sworn the falls rushed down a blank stone wall.

He followed Kral up the gorge which did not run straight, but turned and twisted like a tortured snake. Within three hundred paces they lost sight of the waterfall and only a confused murmur came to their ears. At this point also, the floor of the gorge began to slant upward at a steep pitch. A few more hundred paces and the Armenian, leading the way with renewed caution, drew back, clutching his companion’s arm. A stunted tree stood at a sharp angle of the rock wall, and behind this Kral crouched, pointing.

Looking over his shoulder, the Zaporogian grunted. Beyond the angle the gorge ran on for perhaps eighty paces, then ended in a blank impasse. But on his right hand the cliff seemed curiously altered, and he stared for an instant before he realized that he was looking at a man-made wall. They were almost behind a castle built in a notch of the cliffs. Its wall rose sheer from the edge of a deep crevice; no bridge spanned this chasm, and the only apparent entrance in the wall was a heavy iron-braced door.

“It was by this path that the girl Ayesha escaped,” said Kral. “This gorge runs almost parallel to Ekrem; it narrows to the west and finally comes into the valley beyond where the village stood. The Kurds blocked the entrance there with stones so that it can not be discovered from the outer valley, unless one knows of it. They seldom use this road. And even they know nothing of the tunnel behind the waterfall, or the Caves of the Dead. But yonder door Ayesha will open to Osman Pasha.”

Ivan gnawed his moustache. He yearned to loot the castle himself, but he saw no way to come to it. The chasm was too wide for a man to leap, and anyway, there was no ledge to cling to on the other side.

“By Allah, Kral,” said he, “I’d like to look on this noted valley.”

The Armenian glanced at his bulk and shook his head.

“There is a way we call the Eagle’s Road, but it is not for such as you.”

“By God!” roared the giant Cossack, bristling instantly. “is a skin-clad heathen a better man than a Zaporogian? I’ll go anywhere you dare!”

Kral shrugged his shoulders and led the way back down the gorge until they came within sight of the waterfall again. There he stopped at what looked at first glance like a shallow groove worn by corrosion in the higher cliff-wall. Looking closely Ivan saw a series of shallow hand-holds niched into the solid rock. He twisted his moustache, nonplussed.

“Dogs bite you, Kral,” he grumbled, “an ape could hardly scale these pockmarks.”

“I climbed this ladder before I had seen fifteen winters,” grinned Kral mirthlessly. “Unsling your girdle and I’ll help you as we climb.

Ivan’s pride struggled with his curiosity in his broad face for an instant; then he kicked off his silver-heeled boots and unwound his girdle—a strong length of silk, yards long. One end he bound to his sword-belt, the other he made fast to the Armenian’s girdle. Thus equipped they began the dizzy journey. They climbed slowly but Ivan had an uncomfortable feeling that Kral could have run up the “ladder” like a cat, had he been climbing alone. The Cossack clung to the shallow pits with toes and finger-nails, and time and again the hairs of his scalp-lock bristled and his blood turned to ice as he slipped on the sheer of the cliff. Half a dozen times only Kral’s support saved him. But at last they gained the pinnacle, and Ivan sat down, his feet dangling over the edge, and tried to regain his breath. He glanced down at the narrow shaft up which they had come, and swore. The gorge twisted like a snake-track beneath him, and from his position he looked over the southern wall into the valley of Ekrem, with its river winding serpentine through it.

Smoke still floated lazily up from the blackened masses that had been villages. Down the valley, on the right bank of the river, were pitched a number of hide tents. Ivan made out men swarming about these tents, like milling ants in the distance. They seemed to be saddling horses. There were the Turkomans, Kral said, and pointed out the mouth of a narrow canyon up the valley, and on the southern side, up which, he said, the Algerians were encamped. It was the castle, however, that drew Ivan’s interest.

This castle was set solidly on a promontory of almost solid rock that jutted out from the cliffs and sloped down into the valley. The castle faced the valley, entirely surrounded by a massive wall twenty feet high, and furnished with towers for archers at regular intervals, though there were no towers on the side that backed against the cliff behind. A massive gate flanked on either hand by a tower pierced with slanting slits for arrows commanded the outer slope.

From this gate, the crag slanted to the valley floor, not too steeply to be climbed with ease. But the ascent offered no cover. Men charging up it would be naked to a raking fire from the towers. Ivan shrugged his gigantic shoulders.

“The devil himself couldn’t take that castle by storm, even with cannon. One couldn’t drag bombards up the slope with the dog-brothers on the wall shooting at him. If the cannon were in the gorge—but devil take it, we’ve no cannon. How are we to come at the Soldan’s brother in that pile of rock? Lead us to Osman Pasha. I want to take his head back to the Sjetsch.”

“Be wary if you wish to wear your own, Kazak,” answered Kral grimly. “Look down into the gorge. What do you see?”

“A vastness of bare stone and a fringe of green along the stream,” grunted Ivan, craning his thick neck.

Kral grinned like a wolf. “Taib! And do you notice the fringe is much denser on the right bank, which is likewise higher than the other? Listen! Hidden behind the waterfall we can watch until the Algerians come up the gorge. Then we will hide ourselves among the bushes along the stream and waylay them as they return with the prince. We’ll kill them all except Orkhan, whom we will take captive. Then we will go back along the tunnel through the Caves of the Dead, to the horses, and return to your land.”

“That’s easy,” responded Ivan, twisting his long moustache.“We’ll take a galley from the Turks; we’ll lie in wait along the shore until we see one anchor. Then we’ll swim out by night with our sabers in our teeth, and climb up the chains. Slash, stab, death to you, dog-souls! That’s the way it’ll be. We’ll cut off the heads of the begs and chain the rest to the oars to row us back across the sea. But what’s this?”

Kral stiffened as the Cossack pointed. Men were galloping out of the distant Turkoman camp, lashing their horses across the shallow river. The sunlight struck glints from lance-points. On the castle walls helmets began to sparkle.

“The attack!” cried Kral, glarring. “Jannam! They have changed their plans! They were not to attack until nigh sunset! Chabuk—quick! We must get down the gorge before the Algerians come up it and catch us like rats in a trap!”

He glared down the defile, vanishing to the west like a saber-cut among the cliffs, straining his eyes for glint of shield or helmet that would warn of approaching warriors. As far as he could see the gorge lay bare of life. He urged Ivan over the cliff, and the big warrior cautiously levered his bulk into the shallow groove, cursing bitterly as he bumped his elbows.

Descending seemed even more perilous than ascending, but at last they stood in the gorge, and Kral hastened toward the waterfall, a furtive hurried figure, grotesque in his sheepskins. He sighed as they reached the pool, crossed the ledge and plunged through the fall. But even as they came into the ghostly twilight beyond, he halted, gripping Ivan’s iron-sheathed arm. Above the rush of the water, his keen ears had caught the clink of steel on rock. They looked out through the silver shimmering sheet that made all things look ghostly and unreal, and hid themselves effectually from the eyes of any outside. A shudder shook Kral. They had not gained their refuge an instant too soon.

A band of men was coming along the gorge—tall, strong men in mail hauberks and turban-bound helmets. At their head strode one taller than the rest, whose features, black-bearded and hawk-like as theirs, yet different subtly from those of his followers. His straight grey eyes seemed to look full into the smoldering blue eyes of the giant Cossack, as the corsair glanced at the waterfall. A deep sigh rose from the depths of Ivan’s capacious belly, and his iron hand locked convulsively about his hilt. Impulsively he took a quick step forward, but Kral threw his knotted arms about him and hung on desperately.

“In God’s name, Kazak!” he cried in a frenzied whisper. “Don’t throw away our lives! We have them in a trap. If you rush out now, they’ll shoot you down like a rat; then who’ll take Osman’s head back to the Sjetsch?”

Kral knew the reckless spirit of the Cossacks, for he had wandered among them as a trader, like many of his race.

“I could send a ball through his skull from here,” muttered Ivan.“Nay, it would betray our hiding-place, and even if you brought him down, you could not take his head. Patience, oh patience! I tell you, we will take them all! Not a dog of them shall escape. Hate? Look at that lean vulture in sheepskins and kalpak beside Osman. That is Arap Ali, the Turkoman chief, who slew my young sister and her husband. Do you hate Osman? By the God of my fathers, my very brain reels with madness to leap out upon Arap Ali and rend his throat with my teeth! But patience! Patience!”

The Algerians were crossing the narrow stream, their khalats girt high, holding their matchlocks above their heads to keep the charges dry. On the further bank they halted, in an attitude of listening. Presently, above the rush of the waters, the men in the cave-mouth heard a faint booming sound that came from up the gorge.

“The Kurds are firing from the towers!” whispered Kral. As if it were a signal for which they were waiting, the Algerians shouldered their pieces and started swiftly up the gorge. Kral touched the Cossack’s arm.

“Bide ye here and watch. I’ll hasten back and bring the sir brothers. It will be touch and go if I can get them here before the pirates return.”

“Haste, then,” grunted the giant, and Kral slipped away like a shadow.

In a broad chamber luxuriant with gold-worked tapestries, silken divans and embroidered velvet cushions, the prince Orkhan reclined. He seemed the picture of voluptuous idleness as he lounged there in green satin vest, silken khalat and velvet slippers, a crystal jar of wine at his elbow. His dark eyes, brooding and introspective, were those of a dreamer, whose dreams are tinted with hashish and opium. But there were strong lines in his keen face, not yet erased by sloth and dissipation, and under the rich robe his limbs were clean-cut and hard. His gaze rested on Ayesha, who tensely gripped the bars of a casement, peering eagerly out, but there was a far-away look in his eyes. He seemed not to be aware of the shots, yells and clamor that raged without. Absently he murmured the lines written by a more famous exile of his house:

“Jam-i-Jem nush eyle, ey Jem, bu Firankistan dir—”

Ayesha moved restlessly, throwing him a quick glance over her slim shoulder. Somewhere in this daughter of Iran burned the blood of ancient Aryan conquerors who knew not Kismet. A thousand overlying generations of Oriental fatalism had not washed it out. Outwardly Ayesha was a devout Moslem. At heart she was an untamed pagan. She had fought like a tigress to keep Orkhan from falling into the gulf of degeneracy and resignation his captors had prepared for him. “Allah wills it”—the phrase embraces a whole Turanian philosophy, is at once excuse and consolation for failure. But hot in Ayesha’s veins ran the fierce blood of the yellow-haired kings who trod down Nineveh and Babylon in their road to empire, and recognized no power higher than their own desires. She was the scourge that kept Orkhan stung into life and ambition.

“It is time,” she breathed, turning from the casement. “The sun hangs at the zenith. The turkomans ride up the slope, lashing their steeds and loosing their arrows in vain against the walls. The Kurds shoot down on them—hark to the roar of the firelocks! The bodies of the tribesmen strew the slopes and the survivors give back—now they come on again, like madmen. They are dying for thee, yah khawand! I must hasten—thou shalt yet sit on the throne on the Golden Horn, my lover!”

Casting her lithe form prostrate before him, she kissed his slippered feet in a very ecstasy of passion, then rising, hurried out of the chamber, through another where ten giant black mutes kept guard night and day, and traversing a corridor, found herself in the outer court that lay between the castle and the postern wall. No one had tried to halt her. She was free to come and go within the walls as much as she liked, though Orkhan was for ever guarded by the mutes, and not allowed outside his chamber unless accompanied by Shirkuh himself. Few questions had been asked her when she returned to the castle, feigning great fear of the Turkomans. She had carefully hidden her infatuation for the prince from the eagle eyes of the Kurdish chief, who thought her no more than the tool of Safia.

She crossed the court and approached the door that let into the gorge. One of the warriors leaned there, disgruntled because he could not take part in the fighting that was going on. Skirkuh was a cautious man. The rear of his castle seemed invulnerable, but he never took unnecessary chances. It was not his fault that he was unaware of a traitress in his midst. Wiser men than El Afdal Shirkuh have been gulled and duped by women like Ayesha.

The man on guard was an Uzbek, one of those wandering turbulent warriors who served all the rulers of Asia as mercenaries. He was of broader build than the Kurds, his kinship to the Mongols evidenced by his broad face, slightly slanting eyes and darkly reddish hair. His small turban was knotted over his left ear, his wide girdle loaded with knives and pistols. He leaned on a matchlock, scowling, as Ayesha approached him, her dark eyes eloquent above the filmy veil.

He spat and glowered. “What do you here, woman?” She drew her light mantle closer about her slender shoulders, trembling.

“I am afraid. The cries and shots frighten me, bahadur. The prince is drugged with opium, and there is none to soothe my fears.”

She would have fired the frozen heart of a dead man as she stood there, in her attitude of trembling fear and supplication. The Uzbek plucked his beard.

“Fear not, little gazelle,” he said finally. “I’ll soothe thee, by Allah!” He laid a black-nailed hand on her shoulder and drew her close to him. “None shall lay a finger on a lock of thy hair,” he muttered, “neither Turkoman, Kurd nor—ah!”

Snuggling in his arms, she had slipped a dagger from her sash and thrust it through his bull-throat. His hand lurched from her shoulder to claw at the hilts in his girdle, while the other clutched at his beard, blood spurting between the fingers. He reeled and fell heavily. Ayesha snatched a bunch of keys from his girdle and without a second glance at her victim, ran to the door. Her heart was in her mouth as she swung it open; then she gave a low cry of joy. On the opposite edge of the chasm stood Osman Pasha with his pirates.

A heavy plank, used for a bridge, lay inside the gate, but it was far too heavy for her to handle. Chance had enabled her to use it for her previous escape, when rare carelessness had left it in place across the chasm and unguarded for a few minutes. Osman tossed her the end of a rope, and this she made fast to the hinges of the door. The other end was gripped fast by half a dozen strong men, and three Algerians crossed the crevice, swinging hand over hand as agilely as apes. Then they lifted the plank and spanned the chasm for the rest to cross. There was no sight of a defender. The firing from the front of the castle continued without a break.

“Twenty men stay here and guard the bridge,” snapped Osman. “The rest follow me.”

Leaving their matchlocks, twenty desperate sea-wolves drew their steel and followed their chief. Osman grinned in pure joy as he led them swiftly after the light-footed girl. Such a desperate touch-and-go venture, in the heart of the lion’s lair, stirred his wild blood like wine. As they entered the castle, a servitor sprang up and gaped at them, frozen. Before he could cry out Arap Ali’s razor-edged yataghan sliced through his throat, and the band rushed recklessly on, into the chamber where the ten mutes sprang up, gripping their scimitars. There was a flurry of fierce, silent battling, noiseless except for the hiss and rasp of steel and the croaking gasp of the wounded. Three Algerians died, and over the mangled bodies of the black defenders, Osman Pasha strode into the inner chamber.

Orkhan rose up and his quiet eyes gleamed with an old fire as Osman, with an instinct for dramatics, knelt before him and lifted the hilt of his blood-stained scimitar.

“These are the warriors who shall set you on your throne!” cried Ayesha, clenching her white hands in passionate joy. “Yah Allah! Oh, my lord, what an hour this is!”

“But let us go quickly, before these Kurdish dogs are aware of us,” said Osman, motioning the warriors to draw up about Orkhan in a solid clump of steel. Swiftly they traversed the chambers, crossed the court and approached the gate. But the clang of steel had been heard. Even as the raiders were crossing the bridge, a medley of savage yells rose behind them. Across the courtyard rushed a tall figure in silk and steel, followed by fifty helmeted swordsmen.

“Shirkuh!” screamed Ayesha, paling. “La Allah—”

“Cast down the plank!” roared Osman, springing to the bridge-head.

On each side of the chasm matchlocks flashed and roared. Half a dozen Kurds crumpled, but the four Algerians who had stooped to lift the plank and thrust it off the precipice, went down in a writhing heap before a raking volley, and across the bridge rushed Shirkuh, his hawk-face convulsed, his scimitar flashing about his steel-clad head. Osman Pasha met him breast to breast, and in a glittering whirl of steel, the corsair’s scimitar grated around Shirkuh’s blade, and the keen edge cut through the chain mail and the thick muscles at the base of the Kurd’s neck. Shirkuh staggered and with a wild cry pitched back and over, headlong down the chasm.

In an instant the Algerians had cast the bridge after him, and the Kurds halted, yelling with baffled fury, on the far side of the crevice. What had been their strength now became their weakness. They could not reach their foes. But sheltered by the wall they opened up a vengeful fire, and three more Algerians were struck before the band could get out of range around the angle of the cliff. Osman cursed. Ten men was more than he had expected to lose on that flying raid.

“All but six of you go forward and see that the way is clear,” he ordered. “I will follow more slowly with the prince. Mirza, I could not bring a horse up the defile, but I will have my dogs carry you in a litter of cloaks slung between spears—”

“Allah forbid that I should ride on the shoulders of my deliverers!” cried the young Turk in a ringing voice. “I will not forget this day! Again I am a man! I am Orkhan, son of Selim! I will not forget that, either, Inshallah!”

“Mashallah—God be praised!” whispered the Persian girl. “Oh, my lord, I am blind and dizzy with joy to hear you speak thus! In good truth, you are a man again, and shall be Padishah of all the Osmanli!”

They were within sight of the waterfall. The first detachment had almost reached the stream, when suddenly and unexpectedly as the stroke of a hidden cobra, a pistol cracked in the bushes on the other side, and a warrior fell, his brains oozing from a hole in his skull. Instantly, as if the shot were a signal, there crashed a volley from the bushes. The foremost corsairs went down like ripe corn, and the rest gave back, shouting in rage and terror. They could see no sign of their attackers, save the smoke billowing across the stream, and the dead men at their feet.

“Dog!” roared Osman Pasha, ripping out his scimitar and turning on Arap Ali. “This is your work!”

“Have I matchlocks?” squalled the Turkoman, his dark face ashen. “Ya Ali, alahu! It is the work of devils—”

Osman ran down the gorge toward his demoralized men, cursing madly. He knew the Kurds would rig up some sort of a bridge across the chasm and pursue him, when he would be caught between two fires. Who his assailants were he had no idea. Up the gorge toward the castle he still heard the cracking of matchlocks, and suddenly a great burst of firing seemed to come from the outer valley; but pent in that narrow gorge which muffled and distorted all sounds, he could not be sure.

The smoke had cleared away from the stream, but the Moslems could see nothing except a sinister stirring of the bushes on the opposite bank. They fell back, looking for shelter; there was none, except back up the gorge, into the fangs of the maddened Kurds. They were trapped. They began to loose their matchlocks blindly into the bushes, evoking only mocking laughter from the hidden assailants. Osman started violently as he heard that laughter, and beat down the muzzles of the firelocks.

“Fools! Will you waste powder firing at shadows? Draw your steel and follow me!”

And with the fury of desperation, the Algerians charged headlong at the ambush, their cloaks streaming, their eyes blazing, naked steel glittering in their hands. A raking volley thinned their ranks, but they plunged on, leaped recklessly into the water and began to wade across. And now from among the thick bushes on the further bank rose wild figures, mail-clad or half naked, curved swords in their hands. “Up and at ’em, sir brothers!” bellowed a great voice. “Cut, slash, ho—Cossacks fight!”

A yell of incredulous amazement rose from the Moslems at the sight of the lean eager figures, from whose head-pieces and sabers the sun struck fire. Then with a deep-throated thunderous roar of savagery they closed, and the rasp and clangor of steel rose and re-echoed from the cliffs. The first Algerians to spring up the higher bank fell back into the stream, their heads split, and then the Cossacks, mad with fighting fury, leaped down the bank and met their foes hand to hand, thigh-deep in water that swiftly swirled crimson. There was no quarter asked or given; Cossack and Algerian, they slashed and slew in blind frenzy, froth whitening their moustaches, sweat running into their eyes.

Arap Ali ran into the thick of the melee, mad with fear and rage, his eyes glaring like a rabid dog’s. His curved blade split a Cossack’s shaven head to the teeth; then Kral faced him, bare-handed and screaming.

The Turkoman halted an instant, daunted by the wild beast ferocity in the Armenian’s writhing features; then with an awful cry Kral sprang and his fingers locked like steel in the chief’s throat. Heedless of the dagger, Arap drove again and again into his side, Kral hung on, blood starting from under his finger-nails to mingle with the crimson that gushed from the Turkoman’s torn throat, until, losing their footing, both pitched into the stream. Still tearing and rending they were washed down the current; now one snarling face showed above the crimsoned surface, now another, until at last both vanished for ever.

The Algerians were driven back up the left bank, where they made a brief, bloody stand; then they fell back, dazed and ferocious, toward where Prince Orkhan stared like one dazed, in the shadow of the cliff, with the small knot of warriors Osman had detailed to guard him. Ayesha knelt, gripping his knees. The prince’s eyes were stunned; thrice he moved as though to seize a sword and cast himself into the fray, but Ayesha’s arms were like slender steel bands about his knees. Osman Pasha, breaking away from the battle, hastened to him. The corsair’s scimitar was red to the hilt, his mail hacked, blood dripping from beneath his helmet. All about raged and eddied single combats and struggling groups, as the fighting scattered out over the gorge. The gorge was become a bloodsplashed shambles. Not many were left on either side to fight, but there were more Cossacks on their feet than Muhammadans.

Through the wash of the melee Ivan Sablianka strode, brandishing his great sword in his sledge-like fist. Such as opposed him were beaten down with strokes that shattered leather-covered bucklers, caved in steel caps and clove alike through chain mail, flesh and bone.

“Hey, you rascals!” he roared in his barbarous Turki. “I want your head, Osman, and the fellow beside you there—Orkhan. Don’t be afraid, prince—I won’t harm you. You’ll bring us Cossacks a pretty penny, may I eat pap if you won’t!”

Osman’s keen eyes flickered about, looking desperately for an avenue of escape. He saw the dim groove leading up the cliff, and his keen brain instantly divined its use.

“Chabuk, yah khawand! Quick, my lord!” he whispered. “Up the cliff ! I’ll hold off this barbarian while you climb!”

“Aye!” Ayesha urged eagerly. “Oh, haste! I can climb like a cat! I will come behind you and aid you! It is desperate, but oh, my prince, it is a chance, and this is but to fall back into chains and captivity again!”

She was tense and quivering with eagerness to strive and fight like a wild thing for the man she loved. But the mask of fatalism had descended again on Prince Orkhan. He did not lack courage, even for such a climb. But the paralyzing philosophy of futility had him in its grip. He looked about where the victorious Cossacks were cutting down those who yet lived of his new-found allies. And he bowed his handsome head.

“Nay, this is Kismet. Allah does not will that I should press the throne of my fathers. Nay, what man can escape his fate?”

Ayesha blenched, her eyes flaring in a sort of horror, her hands catching at her locks. Osman, realizing the prince’s mood, whirled, sprang for the shaft himself and went up it as only a sailor could climb. With a roar Ivan charged after him, forgetting all about the prince. Cossacks were approaching, shaking red drops from their sabers. Orkhan spread his hands resignedly, and Ayesha watched him, her lips parted in dumb agony.

“Che arz kunam?” he said simply, facing his new captors. “Take me if you will; I am Orkhan.”

Ayesha swayed, her hands clasped over her closed eyes, as if about to faint. Then springing like a flash of light, she thrust her dagger straight through Prince Orkhan’s heart and he died on his feet, so quickly that he scarcely felt the sting of the stroke. And as he fell, she turned the point and rove it home in her own breast, and sank down beside her lover. Moaning softly, she cradled his princely head in her weakening arms, while the rough Cossacks stood about, awed and not understanding.

A sound up the gorge made them left their heads and stare at each other. There was but a handful, weary and dazed with battle, their garments soaked with water and blood, their sabers clotted and nicked. Ivan was gone, and they were at a loss as to what to do.

“Get back into the tunnel, brothers,” grunted Togrukh. “I hear men coming down the gorge. Get back through the tunnel to the place where we left the horses. Saddle and make ready to ride. I’m going after Ivan.”

They obeyed and he started up the cliff, swearing at the shallow hand-holds. They had scarcely vanished behind the silvery sheet, and he had not reached the crest of the cliff, when a number of men came into sight, marching hurriedly. The gorge was thronged with warlike figures. Togrukh, looking down with the curiosity of the Cossack, saw the turbans and khalats of the Kurds of the castle, and with them the peaked white caps of Turkish janizaries. One wore half-a-dozen bird-of-paradise plumes in his cap, and Togrukh gaped to recognize the Agha of the janizaries, the third man of power in the Ottoman empire. He and his followers were dusty, as if from long hard riding. Glancing toward the valley, the lean Cossack saw the Agha’s standard of three white horse-tails flying from the castle gate, and along the river the sheepskin-clad Turkomans were riding like mad for the hills, pursued by horsemen in glittering mail—the Turkish spahis. Togrukh shook his head in wonder. What brought the Agha of the janizaries in such array to the lonely valley of Ekrem?

Down in the gorge rose a chorus of horrified voices, as the newcomers halted dumbfounded among the corpses. The Agha knelt beside the dead man and the dying girl.

“Allah! It is Prince Orkhan!”

“He is beyond your power,” murmured Ayesha. “You can not hurt him any more. I would have made him king. But you had robbed him of his manhood—so I killed him—better an honorable death, than—”

“But I bring him the crown of Turkey!” cried the Agha desperately. “Murad is dead, and the people have risen against Safia’s half-caste son—”

“Too late!” whispered Ayesha. “Too—too—late!” Her dark head sank on her white round arm like a child when it falls asleep.

As Ivan Sablianka went up the shaft-ladder, Kral was not there to aid him, because Kral lay dead beside dead Arap Ali under the blood-stained stream. But this time hate spurred him on, and he swarmed up the precarious path as recklessly as if he clambered a ship’s ratlines. Bits of crumbling stone gave way beneath his grasp and rattled down the cliff in tiny avalanches, but somehow he cheated death each time, and heaved relentlessly upward. He was not far behind Osman Pasha when the corsair came out on the cliff and set off through the stunted firs. Ivan came after him, his long legs carrying his giant frame across the ground at a surprizing rate, and presently Osman, turning and seeing he had but one foe to deal with, faced round with a curse.

A fierce grin bristled the corsair’s curly black beard. Here was a huge frame on which he could carve his savage disgust at the muddling of his plans. Only a few months before he had been the most feared sea-lord in the world, with the broad blue Mediterranean at his feet. Now he was shorn of all following and power, except that gripped in his strong right hand, and locked in his skull. He was too much of the true adventurer to waste time in bemoaning his fall, but the chance of hewing down this pestiferous Cossack gave him a grim satisfaction.