Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

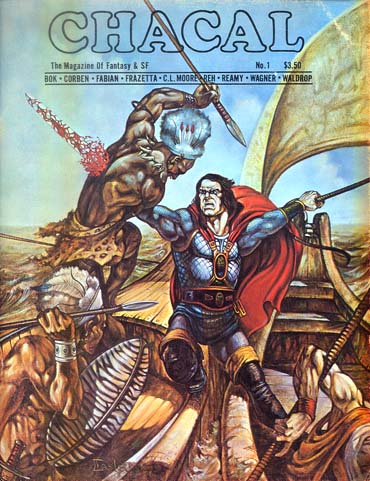

Published in Chacal #1 (Winter 1976). This version is taken from Howard’s original typescript.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Towers reel as they burst asunder,

Streets run red in the butchered town;

Standards fall and the lines go under

And the iron horsemen ride me down.

Out of the strangling dust around me

Let me ride for my hour is nigh,

From the walls that prison, the hoofs that ground me,

To the sun and the desert wind to die.

Allaho akbar! There is no God but God. These happenings I, Kosru Malik, chronicle that men may know truth thereby. For I have seen madness beyond human reckoning; aye, I have ridden the road of Azrael that is the Road of Death, and have seen mailed men fall like garnered grain; and here I detail the truths of that madness and of the doom of Kizilshehr the Strong, the Red City, which has faded like a summer cloud in the blue skies.

Thus was the beginning. As I sat in peace in the camp of Muhammad Khan, sultan of Kizilshehr, conversing with divers warriors on the merits of the verses of one Omar Khayyam, a tent maker of Nishapur and a doughty toper, suddenly I was aware that one came close to me, and I felt anger burn in his gaze, as a man feels the eyes of a hungry tiger upon him. I looked up and as the firelight took his bearded face, I felt my own eyes blaze with an old hate. For it was Moktra Mirza, the Kurd, who stood above me and there was an old feud between us. I have scant love for any Kurd, but this dog I hated. I had not known he was in the camp of Muhammad Khan, whither I had ridden alone at dusk, but where the lion feasts, there the jackals gather.

No word passed between us. Moktra Mirza had his hand on his blade and when he saw he was perceived, he drew with a rasp of steel. But he was slow as an ox. Gathering my feet under me, I shot erect, my scimitar springing to my hand and as I leaped I struck, and the keen edge sheared through his neck cords.

Even as he crumpled, gushing blood, I sprang across the fire and ran swiftly through the maze of tents, hearing a clamor of pursuit behind me. Sentries patrolled the camp, and ahead of me I saw one on a tall bay, who sat gaping at me. I wasted no time but running up to him, I seized him by the leg and cast him from the saddle.

The bay horse reared as I swung up, and was gone like an arrow, I bending low on the saddle-peak for fear of shafts. I gave the bay his head and in an instant we were past the horse-lines and the sentries who gave tongue like a pack of hounds, and the fires were dwindling behind us.

We struck the open desert, flying like the wind, and my heart was glad. The blood of my foe was on my blade, a good steed between my knees, the stars of the desert above me, the night wind in my face. A Turk need ask no more.

The bay was a better horse than the one I had left in the camp, and the saddle was a goodly one, richly brocaded and worked in Persian leather.

For a time I rode with a loose rein, then as I heard no sound of pursuit, I slowed the bay to a walk, for who rides on a weary horse in the desert, dices with Death. Far behind me I saw the twinkling of the camp-fires and wondered that a hundred Kurds were not howling on my trail. But so swiftly had the deed been done and so swiftly had I fled, that the avengers were bemused and though men followed, hot with hate, they missed my trail in the dark, I learned later.

I had ridden west by blind chance and now I came on to the old caravan route that once led from Edessa to Kizilshehr and Shiraz. Even then it was almost abandoned because of the Frankish robbers. It came to me that I would ride to the caliphs and lend them my sword, so I rode leisurely across the desert which here is a very broken land, flat, sandy levels giving way to rugged stretches of ravines and low hills, and these again running out into plains. The breezes from the Persian Gulf cooled me and even while I listened for the drum of hoofs behind me, I dreamed of the days of my early childhood when I rode, night-herding the ponies, on the great upland plains far to the East, beyond the Oxus.

And then after some hours, I heard the sound of men and horses, but from in front of me. Far ahead I made out, in the dim starlight, a line of horsemen and lurching bulk I knew to be a wagon such as the Persians use to transport their wealth and their harems. Some caravan bound for Muhammad’s camp, or for Kizilshehr beyond, I thought, and did not wish to be seen by them, who might put the avengers on my trail.

So I reined aside into a broken maze of gullies, and sitting my steed behind a huge boulder, I watched the travellers. They approached my hiding place and I, straining my eyes in the vague light, saw that they were Seljuk Turks, heavily armed. One who seemed a leader sate his horse in a manner somehow familiar to me, and I knew I had seen him before. I decided that the wagon must contain some princess, and wondered at the fewness of the guards. There was not above thirty of them, enough to resist the attack of nomad raiders, no doubt, but certainly not a strong enough force to beat off the Franks who were wont to swoop down on Moslem wayfarers. And this puzzled me, because men, horses and wagon had the look of long travel, as if from beyond the Caliphate. And beyond the Caliphate lay a waste of Frankish robbers.

Now the wagon was abreast of me, and one of the wheels creaking in the rough ground, lurched into a depression and hung there. The mules, after the manner of mules, lunged once and then ceased pulling, and the rider who seemed familiar rode up with a torch and cursed. By the light of the torch I recognized him—one Abdullah Bey, a Persian noble high in the esteem of Muhammad Khan—a tall, lean man and a somber one, more Arab than Persian.

Now the leather curtains of the wagon parted and a girl looked out—I saw her young face by the flare of the torch. But Abdullah Bey thrust her back angrily and closed the curtains. Then he shouted to his men, a dozen of whom dismounted and put their shoulders to the wheel. With much grunting and cursing they lifted the wheel free, and soon the wagon lurched on again, and it and the horsemen faded and dwindled in my sight until all were shadows far out on the desert.

And I took up my journey again, wondering; for in the light of the torch I had seen the unveiled face of the girl in the wagon, and she was a Frank, and one of great beauty. What was the meaning of Seljuks on the road from Edessa, commanded by a Persian nobleman, and guarding a girl of the Nazarenes? I concluded that these Turks had captured her in a raid on Edessa or the kingdom of Jerusalem and were taking her to Kizilshehr or Shiraz to sell to some emir, and so dismissed the matter from my mind.

The bay was fresh and I had a mind to put a long way between me and the Persian army, so I rode slowly but steadily all night. And in the first white blaze of dawn, I met a horseman riding hard out of the west.

His steed was a long limbed roan that reeled from fatigue. The rider was an iron man—clad in close meshed mail from head to foot, with a heavy vizorless helmet on his head. And I spurred my steed to gallop for this was a Frank—and he was alone and on a tired horse.

He saw me coming and he cast his long lance into the sand and drew his sword, for he knew his steed was too weary to charge. And as I swooped down as a hawk swoops on its prey, I suddenly gave a shout and lowering my blade, set my steed back on his haunches, almost beside the Frank.

“Now by the beard of the Prophet,” said I. “We are well met, Sir Eric de Cogan!”

He gazed at me in surprize. He was no older than I, broad shouldered, long limbed and yellow haired. Now his face was haggard and weary as if he had ridden hard without sleep, but it was the face of a warrior, as his body was that of a warrior. I lack but an inch and a fraction of six feet in height as the Franks reckon a man’s stature, but Sir Eric was half a head taller.

“You know me,” said he, “but I do not remember you.”

“Ha!” quoth I, “we Saracens look all alike to you Franks! But I remember you, by Allah! Sir Eric, do you not remember the taking of Jerusalem and the Moslem boy you protected from your own warriors?”

Aye, I remembered! I was but a youth, newly come to Palestine, and I slipped through the besieging armies into the city the very dawn it fell. I was not used to street fighting. The noise, the shouting and the crashing of the shattered gates bewildered me, the dust and the foul smells of the strange city stifled me and maddened me. The Franks came over the walls and red Purgatory broke in the streets of Jerusalem. Their iron horsemen rode over the ruins of the gates and their horses tramped fetlock deep in blood. The Crusaders shouted hosannas and slew like blood-mad tigers and the mangled bodies of the Faithful choked the streets.

In a blind red whirl and chaos of destruction and delirium, I found myself slashing vainly against giants who seemed built of solid iron. Slipping in the filth of a blood-running gutter I hacked blindly in the dust and smoke and then the horsemen rode me down and trampled me. As I staggered up, bloody and dazed, a great bellowing monster of a man strode on foot out of the carnage swinging an iron mace. I had never fought Franks and did not then know the power of the terrible blows they deal in hand-to-hand fighting. In my youth and pride and inexperience I stood my ground and sought to match blows with the Frank, but that whistling mace shivered my sword to bits, shattered my shoulder-bone and dashed me half dead into the blood-stained dust.

Then the giant bestrode me, and as he swung up his mace to dash out my brains, the bitterness of death took me by the throat. For I was young and in one blinding instant I saw again the sweet upland grass and the blue of the desert sky, and the tents of my tribe by the blue Oxus. Aye—life is sweet to the young.

Then out of the whirling smoke came another—a golden haired youth of my own age, but taller. His sword was red to the hilt, but his eyes were haunted. He cried out to the great Frank, and though I could not understand, I knew, vaguely, as one knows in a dream, that the youth asked that my life be spared—for his soul was sick with the slaughter. But the giant foamed at the mouth and roared like a beast, as he again raised his mace—and the youth leaped like a panther and thrust his long straight sword through his throat, so the giant fell down and died in the dust beside me.

Then the youth knelt at my side and made to staunch my wounds, speaking to me in halting Arabic. But I mumbled: “This is no place for a Chagatai to die. Set me on a horse and let me go. These walls shut out the sun and the dust of the streets chokes me. Let me die with the wind and the sun in my face.”

We were nigh the outer wall and all gates had been shattered. The youth caught one of the riderless horses which raced through the streets, and lifted me into the saddle. And I let the reins lie along the horse’s neck and he went from the city as an arrow goes from a bow, for he too was desert bred and he yearned for the open lands. I rode as a man rides in a dream, clinging to the saddle, and knowing only that the walls and the dust and the blood of the city no longer stifled me, and that I would die in the desert after all, which is the place for a Chagatai to die. And so I rode until all knowledge went from me.

Shall the grey wolf slink at the mastiff ’s heel?

Shall the ties of blood grow weak and dim?—

By smoke and slaughter, by fire and steel,

He is my brother—I ride with him.

Now as I gazed into the clear grey eyes of the Frank, all this came back to me and my heart was glad.

“What!” said he. “Are you that one whom I set on a horse and saw ride out of the city gate to die in the desert?”

“I am he—Kosru Malik,” said I. “I did not die—we Turks are harder than cats to kill. The good steed, running at random, brought me into an Arab camp and they dressed my wounds and cared for me through the months I lay helpless of my wounds. Aye—I was more than half dead when you lifted me on the Arab horse, and the shrieks and red sights of the butchered city swam before me like a dim nightmare. But I remembered your face and the lion on your shield.

“When I might ride again, I asked men of the Frankish youth who bore the lion-shield and they told me it was Sir Eric de Cogan of that part of Frankistan that is called England, newly come to the East but already a knight. Ten years have passed since that crimson day, Sir Eric. Since then I have had fleeting glances of your shield gleaming like a star in the mist, in the forefront of battle, or glittering on the walls of towns we besieged, but until now I have not met you face to face.

“And my heart is glad for I would pay you the debt I owe you.”

His face was shadowed. “Aye—I remember it all. You are in truth that youth. I was sick—sick—triply sick of blood-shed. The Crusaders went mad once they were within the walls. When I saw you, a lad of my own age, about to be butchered in cold blood by one I knew to be a brute and a vandal, a swine and a desecrator of the Cross he wore, my brain snapped.”

“And you slew one of your own race to save a Saracen,” said I. “Aye—my blade has drunk deep in Frankish blood since that day, my brother, but I can remember a friend as well as an enemy. Whither do you ride? To seek a vengeance? I will ride with you.”

“I ride against your own people, Kosru Malik,” he warned.

“My people? Bah! Are Persians my people? The blood of a Kurd is scarcely dry on my scimitar. And I am no Seljuk.”

“Aye,” he agreed, “I have heard that you are a Chagatai.”

“Aye, so,” said I, “by the beard of the Prophet, on whom peace, Tashkend and Samarcand and Khiva and Bokhara are more to me than Trebizond and Shiraz and Antioch. You let blood of your breed to succor me—am I a dog that I should shirk my obligations? Nay, brother, I ride with thee!”

“Then turn your steed on the track you have come and let us be on,” he said, as one who is consumed with wild impatience. “I will tell you the whole tale, and a foul tale it is and one which I shame to tell, for the disgrace it puts on a man who wears the Cross of Holy Crusade.

“Know then, that in Edessa dwells one William de Brose, Seneschal to the Count of Edessa. To him lately has come from France his young niece Ettaire. Now harken, Kosru Malik, to the tale of man’s unspeakable infamy! The girl vanished and her uncle would give me no answer as to her whereabouts. In desperation I sought to gain entrance to his castle, which lies in the disputed land beyond Edessa’s south-eastern border, but was apprehended by a man-at-arms close in the council of de Brose. To this man I gave a death wound, and as he died, fearful of damnation, he gasped out the whole vile plot.

“William de Brose plots to wrest Edessa from his lord and to this end has received secret envoys from Muhammad Khan, sultan of Kizilshehr. The Persian has promised to come to the aid of the rebels when the time comes. Edessa will become part of the Kizilshehr sultanate and de Brose will rule there as a sort of satrap.

“Doubtless each plans to trick the other eventually—Muhammad demanded from de Brose a sign of good faith. And de Brose, the beast unspeakable, as a token of good will sends Ettaire to the sultan!”

Sir Eric’s iron hand was knotted in his horse’s mane and his eyes gleamed like a roused tiger’s.

“Such was the dying soldier’s tale,” he continued. “Already Ettaire had been sent away with an escort of Seljuks—with whom de Brose intrigues as well. Since I learned this I have ridden hard—by the saints, you would swear I lied were I to tell you how swiftly I have covered the long weary miles between this spot and Edessa! Days and nights have merged into one dim maze, so I hardly remember myself how I have fed myself and my steed, how or when I have snatched brief moments of sleep, or how I have eluded or fought my way through hostile lands. This steed I took from a wandering Arab when my own fell from exhaustion—surely Ettaire and her captives cannot be far ahead of me.”

I told him of the caravan I had seen in the night and he cried out with fierce eagerness but I caught his rein. “Wait, my brother,” I said, “your steed is exhausted. Besides now the maid is already with Muhammad Khan.”

Sir Eric groaned.

“But how can that be? Surely they cannot yet have reached Kizilshehr.”

“They will come to Muhammad ere they come to Kizilshehr,” I answered. “The sultan is out with his hawks and they are camped on the road to the city. I was in their camp last night.”

Sir Eric’s eyes were grim. “Then all the more reason for haste. Ettaire shall not bide in the clutches of the paynim while I live—”

“Wait!” I repeated. “Muhammad Khan will not harm her. He may keep her in the camp with him, or he may send her on to Kizilshehr. But for the time being she is safe. Muhammad is out on sterner business than love making. Have you wondered why he is encamped with his slayers?”

Sir Eric shook his head.

“I supposed the Kharesmians were moving against him.”

“Nay, since Muhammad tore Kizilshehr from the empire, the Shah has not dared attack him, for he has turned Sunnite and claimed protection of the Caliphate. And for this reason many Seljuks and Kurds flock to him. He has high ambitions. He sees himself the Lion of Islam. And this is but the beginning. He may yet revive the powers of Islam with himself at the head.

“But now he waits the coming of Ali bin Sulieman, who has ridden up from Araby with five hundred desert hawks and swept a raid far into the borders of the sultanate. Ali is a thorn in Muhammad’s flesh, but now he has the Arab in a trap. He has been outlawed by the Caliphs—if he rides to the west their warriors will cut him to pieces. A single rider, like yourself, might get through; not five hundred men. Ali must ride south to gain Arabia—and Muhammad is between with a thousand men. While the Arabs were looting and burning on the borders, the Persians cut in behind them with swift marches.

“Now let me venture to advise you, my brother. Your horse has done all he may, nor will it aid us or the girl to go riding into Muhammad’s camp and be cut down. But less than a league yonder lies a village where we can eat and rest our horses. Then when your steed is fit for the road again, we will ride to the Persian camp and steal the girl from under Muhammad’s nose.”

Sir Eric saw the wisdom of my words, though he chafed fiercely at the delay, as is the manner of Franks, who can endure any hardship but that of waiting and who have learned all things but patience.

But we rode to the village, a squalid, miserable cluster of huts, whose people had been oppressed by so many different conquerors that they no longer knew what blood they were. Seeing the unusual sight of Frank and Saracen riding together, they at once assumed that the two conquering nations had combined to plunder them. Such being the nature of humans, who would think it strange to see wolf and wildcat combine to loot the rabbit’s den.

When they realized we were not about to cut their throats they almost died of gratitude and immediately brought us of food their best—and sorry stuff it was—and cared for our steeds as we directed. As we ate we conversed; I had heard much of Sir Eric de Cogan, for his name is known to every man in Outremer, as the Franks call it, whether Caphar or Believer, and the name of Kosru Malik is not smoke for the wind to blow from men’s ears. He knew me by reputation though he had never linked the name with the lad he saved from his people when Jerusalem was sacked.

We had no difficulty in understanding each other now, for he spoke Turki like a Seljuk, and I had long learned the speech of the Franks, especially the tongue of those Franks who are called Normans. These are the leaders and the strongest of the Franks—the craftiest, fiercest and most cruel of all the Nazarenes. Of such was Sir Eric, though he differed from most of them in many ways. When I spoke of this he said it was because he was half Saxon. This people, he said, once ruled the isle of England, that lies west of Frankistan, and the Normans had come from a land called France, and conquered them, as the Seljuks conquered the Arabs, nearly half a century before. They had intermarried with the conquered, said Sir Eric, and he was the son of a Saxon princess and a knight who rode with William the Conqueror, the emir of the Normans.

He told me—and from weariness fell asleep in the telling—of the great battle which the Normans call Senlac and the Saxons Hastings, in which the emir William overcame his foes, and deeply did I wish that I had been there, for there is no fairer sight to me than to see Franks cutting each other’s throats.

Pent between tiger and wolf,

Only our lives to lose—

The dice will fall as the gods decide,

But who knows what may first betide?

And blind are all of the roads we ride—

Choose, then, my brother, choose!

As the sun dipped westward Sir Eric woke and cursed himself for his sloth; and we mounted and rode at a canter back along the way I had come, and over which the trail of the caravan was still to be seen. We went warily for it was in my mind that Muhammad Khan would have outriders to see that Ali bin Sulieman did not slip past him. And indeed, as dusk began to fall, we saw the last light of day glint on spear tips and steel caps to the north and west, but we went with care and escaped notice. At about midnight we came upon the site of the Persian camp but it was deserted and the tracks led south-eastward.

“Scouts have relayed word by signal smokes that Ali bin Sulieman is riding hard for Araby,” said I, “and Muhammad has marched to cut him off. He is keeping well in touch with his foes.”

“Why does the Persian ride with only a thousand men?” asked Sir Eric. “Two to one are no great odds against men like the Bedouins.”

“To trap the Arab, speed is necessary,” said I. “The sultan can shift his thousand riders as easily and swiftly as a chess player moves his piece. He has sent riders to harry Ali and herd him toward the route across which lies Muhammad with his thousand hard-bitten slayers. We have seen, far away, all evening, signal smokes hanging like serpents along the sky-line. Where-ever the Arabs ride, men send up smoke, and these smokes are seen by other scouts far away, who likewise send up smoke that may be seen by Muhammad’s outriders.”

Sir Eric had been searching among the tracks with flint, steel and tinder, and now he announced: “Here is the track of Ettaire’s wagon. See—the left hind wheel has been broken at some time and mended with rawhide—the mark in the tracks shows plainly. The stars give light enough to show if a wagon turns off from the rest. Muhammad may keep the girl with him, or he may send her on to his harem at Kizilshehr.”

So we rode on swiftly, keeping good watch, and no wagon train turned off. For time to time Sir Eric dismounted and sought with flint and steel until he found the mark of the hide-bound wheel again. So we progressed and just before the darkness that precedes dawn, we came to the camp of Muhammad Khan which lay in a wide reach of level desert land at the foot of a jagged tangle of bare, gully torn hills.

At first I thought the thousand of Muhammad had become a mighty host, for many fires blazed on the plain, straggling in a vast half circle. The warriors were wide awake, many of them, and we could hear them singing and shouting as they feasted and whetted their scimitars and strung their bows. From the darkness that hid us from their eyes, we could make out the bulks of steeds standing nearby in readiness and many riders went to and fro between the fires for no apparent reason.

“They have Ali bin Sulieman in a trap,” I muttered. “All this show is to fool scouts—a man watching from those hills would swear ten thousand warriors camped here. They fear he might try to break through in the night.”

“But where are the Arabs?”

I shook my head in doubt. The hills beyond the plain loomed dark and silent. No single gleam betrayed a fire among them. At that point the hills jutted far out into the plains and none could ride down from them without being seen.

“It must be that scouts have reported Ali is riding hither, through the night,” said Sir Eric, “and they wait to cut him off. But look! That tent—the only one pitched in camp—is that not Muhammad’s? They have not put up the tents of the emirs because they feared a sudden attack. The warriors keep watch or sleep beneath the wagons. And look—that smaller fire which flickers furtherest from the hills, somewhat apart from the rest. A wagon stands beside it, and would not the sultan place Ettaire furtherest from the direction in which the enemy comes? Let us see to that wagon.”

So the first step in the madness was taken. On the western side the plain was broken with many deep ravines. In one of these we left our horses and in the deepening darkness stole forward on foot. Allah willed it that we should not be ridden down by any of the horsemen who constantly patrolled the plain, and presently it came to pass that we lay on our bellies a hundred paces from the wagon, which I now recognized as indeed the one I had passed the night before.

“Remain here,” I whispered, “I have a plan. Bide here, and if you hear a sudden outcry or see me attacked, flee, for you can do no good by remaining.”

He cursed me beneath his breath as is the custom of Franks when a sensible course is suggested to them, but when I swiftly whispered my plan, he grudgingly agreed to let me try it.

So I crawled away for a few yards, then rose and walked boldly to the wagon. One warrior stood on guard, with shield and drawn scimitar, and I hoped it was one of the Seljuks who had brought the girl, since if it were so, he might not know me, or that my life was forfeit in the camp. But when I approached I saw that though indeed a Turk, he was a warrior of the sultan’s own body-guard. But he had already seen me, so I walked boldly up to him, seeking to keep my face turned from the fire.

“The sultan bids me bring the girl to his tent,” I said gruffly, and the Seljuk glared at me uncertainly.

“What talk is this?” he growled. “When her caravan arrived at the camp, the sultan took time only to glance at her, for much was afoot, and word had come of the movements of the Arab dogs. Earlier in the night he had her before him, but sent her away, saying her kisses would taste sweeter after the dry fury of battle. Well meseemeth he is sorely smitten with the infidel hussy, but is it likely he would break the sleep he snatches now—”

“Would you argue with the royal order?” I asked impatiently. “Do you burn to sit on a stake, or yearn to have your hide flayed from you? Harken and obey!”

But his suspicions were aroused. Just as I thought him about to step back and wake the girl, like a flash he caught my shoulder and swung me around so that the firelight shone full on my face.

“Ha!” he barked like a jackal, “Kosru Malik—!”

His blade was already glittering above my head. I caught his arm with my left hand and his throat with my right, strangling the yell in his gullet. We plunged to earth together, and wrestled and tore like a pair of peasants, and his eyes were starting from his head, when he drove his knee into my groin. The sudden pain made me relax my grip for an instant, and he ripped his sword-arm free and the blade shot for my throat like a gleam of light. But in that instant there was a sound like an axe driven deep into a tree-trunk, the Seljuk’s whole frame jerked convulsively, blood and brains spattered in my face and the scimitar fell harmlessly on my mailed chest. Sir Eric had come up while we fought and seeing my peril, split the warrior’s skull with a single blow of his long straight sword.

I rose, drawing my scimitar and looked about; the warriors still revelled by the fires a bow-shot away; seemingly no one had heard or seen that short fierce fight in the shadow of the wagon.

“Swift! The girl, Sir Eric!” I hissed, and stepping quickly to the wagon he drew aside the curtain and said softly, “Ettaire!”

She had been wakened by the struggle and I heard a low cry of joy and love as two white arms went around Sir Eric’s mailed neck and over his shoulder I saw the face of the girl I had passed on the road to Edessa.

They whispered swiftly to one another and then he lifted her out and sat her gently down. Allah—little more than a child she was, as I could see by the firelight—slim and frail, with deep eyes, grey like Sir Eric’s, but soft instead of cold and steely. Comely enough, though a trifle slight to my way of thinking. When she saw the firelight on my dark face and drawn scimitar she cried out sharply and shrank back against Sir Eric, but he soothed her.

“Be not afraid, child,” said he. “This is our good friend, Kosru Malik, the Chagatai. Let us go swiftly; any moment sentries may ride past this fire.”

Her slippers were soft and she but little used to treading the desert. Sir Eric bore her like a child in his mighty arms as we stole back to the ravine where he had left the horses. It was the will of Allah that we reached them without mishap, but even as we rode up out of the ravine, the Frank holding Ettaire before him, we heard the rattle of hoofs hard by.

“Ride for the hills,” muttered Sir Eric. “There is a large band of riders close at our heels, doubtless reenforcements. If we turn back we will ride into them. Perchance we can reach the hills before dawn breaks, then we can turn back the way we wish to go.”

So we trotted out on the plain in the last darkness before dawn, made still darker by a thick, clammy fog, with the tramp of hoofs and the jingle of armor and reins close at our heels. I did not think they were reenforcements but a band of scouts, since they did not turn in to the fires but made straight out across the levels toward the hills, driving us before them, though they knew it not. Surely, I thought, Muhammad knows that hostile eyes are on him, hence this milling to and fro of riders to give an impression of great numbers.

The hoofs dwindled behind us as the scouts turned aside or rode back to the lines. The plain was alive with small groups of horsemen who rode to and fro like ghosts in the deep darkness. On each side we heard the stamp of their horses and the rattle of their arms. Tenseness gripped us. Already there was a hint of dawn in the sky, though the heavy fog veiled all. In the darkness the riders mistook us for their comrades, so far, but quickly the early light would betray us.

Once a band of horsemen swung close and hailed us; I answered quickly in Turki and they reined away, satisfied. There were many Seljuks in Muhammad’s army, yet had they come a pace closer they would have made out Sir Eric’s stature and Frankish apparel. As it was the darkness and the mists clumped all objects into shadowy masses, for the stars were dimmed and the sun was not yet.

Then the noises were all behind us, the mists thinned in light that flowed suddenly across the hills in a white tide, stars vanished and the vague shadows about us took the forms of ravines, boulders and cactus. Then it was full dawn but we were among the defiles, out of sight of the plains, which were still veiled in the mists that had forsaken the higher levels.

Sir Eric tilted up the white face of the girl and kissed her tenderly.

“Ettaire,” said he, “we are encompassed by foes, but now my heart is light.”

“And mine,my lord!” she answered, clinging to him. “I knew you would come! Oh, Eric, did the pagan lord speak truth when he said mine own uncle gave me into slavery?”

“I fear so, little Ettaire,” said he gently. “His heart is blacker than night.”

“What was Muhammad’s word to you?” I broke in.

“When I was first taken to him, upon reaching the Moslem camp,” she answered, “there was much confusion and haste, for the infidels were breaking camp and preparing to march. The sultan looked on me and spake kindly to me, bidding me not fear. When I begged to be sent back to my uncle, he told me I was a gift from my uncle. Then he gave orders that I be given tender care and rode on with his generals. I was put back in the wagon and thereafter stayed there, sleeping a little, until early last night when I was again taken to the sultan. He talked with me a space and offered me no indignity, though his talk frightened me. For his eyes glowed fiercely on me, and he swore he would make me his queen—that he would build a pyramid of skulls in my honor and fling the turbans of shahs and caliphs at my feet. But he sent me back to my wagon, saying that when he next came to me, he would bring the head of Ali bin Sulieman for a bridal gift.”

“I like it not,” said I uneasily. “This is madness—the talk of a Tatar chief rather than that of civilized Moslem ruler. If Muhammad has been fired with love for you, he will move all Hell to take you.”

“Nay,” said Sir Eric, “I—”

And at that moment a half score of ragged figures leaped from the rocks and seized our reins. Ettaire screamed and I made to draw my scimitar; it is not meet that a dog of the Bedoui seize thus the rein of a son of Turan. But Sir Eric caught my arm. His own sword was in its sheath, but he made no move to draw it, speaking instead in sonorous Arabic, as a man speaks who expects to be obeyed: “We are well met, children of the tents; lead us therefore to Ali bin Sulieman whom we seek.”

At this the Arabs were taken somewhat aback and they gazed at each other.

“Cut them down,” growled one. “They are Muhammad’s spies.”

“Aye,” gibed Sir Eric, “spies ever carry their women-folk with them. Fools! We have ridden hard to find Ali bin Sulieman. If you hinder us, your hides will answer. Lead us to your chief.”

“Aye,” snarled one they called Yurzed, who seemed to be a sort of beg or lesser chief among them, “Ali bin Sulieman knows how to deal with spies. We will take you to him, as sheep are taken to the butcher. Give up thy swords, sons of evil!”

Sir Eric nodded to my glance, drawing his own long blade and delivering it hilt first.

“Even this was to come to pass,” said I bitterly. “Lo, I eat dust—take my hilt, dog—would it was the point I was passing through thy ribs.”

Yurzed grinned like a wolf. “Be at ease, Turk—time thy steel learnt the feel of a man’s hand.”

“Handle it carefully,” I snarled. “I swear, when it comes back into my hands I will bathe it in swine’s blood to cleanse it of the pollution of thy filthy fingers.”

I thought the veins in his forehead would burst with fury, but with a howl of rage, he turned his back on us, and we perforce followed him, with his ragged wolves holding tight to our reins.

I saw Sir Eric’s plan, though we dared not speak to each other. There was no doubt but that the hills swarmed with Bedouins. To seek to hack our way through them were madness. If we joined forces with them, we had a chance to live, scant though it was. If not—well, these dogs love a Turk little and a Frank none.

On all sides we caught glimpses of hairy men in dirty garments, watching us from behind rocks or from among ravines, with hard, hawk-like eyes; and presently we came to a sort of natural basin where some five hundred splendid Arab steeds sought the scanty grass that straggled there. My very mouth watered. By Allah, these Bedoui be dogs and sons of dogs, but they breed good horse flesh!

A hundred or so warriors watched the horses—tall, lean men, hard as the desert that bred them, with steel caps, round bucklers, mail shirts, long sabers and lances. No sign of fire was seen and the men looked worn and evil as with hunger and hard riding. Little loot had they of that raid! Somewhat apart from them on a sort of knoll sat a group of older warriors and there our captors led us.

Ali bin Sulieman we knew at once; like all his race he was tall and wide shouldered, tall as Sir Eric but lacking the Frank’s massiveness, built with the savage economy of a desert wolf. His eyes were piercing and menacing, his face lean and cruel. Sir Eric did not wait for him to speak: “Ali bin Sulieman,” said the Frank, “we have brought you two good swords.”

Ali bin Sulieman snarled as if Sir Eric had suggested cutting his throat.

“What is this?” he snapped, and Yurzed spake, saying: “These Franks and this dog of a Turk we found in the fringe of the hills, just at the lifting of dawn. They came from toward the Persian camp. Be on your guard, Ali bin Sulieman; Franks are crafty in speech, and this Turk is no Seljuk, meseemeth, but some devil from the East.”

“Aye,” Ali grinned ferociously, “we have notables among us! The Turk is Kosru Malik the Chagatai, whose trail the ravens follow. And unless I am mad, that shield is the shield of Sir Eric de Cogan.”

“Trust them not,” urged Yurzed. “Let us throw their heads to the Persian dogs.”

Sir Eric laughed and his eyes grew cold and hard as is the manner of Franks when they stare into the naked face of Doom.

“Many shall die first, though our swords be taken from us,” quoth he, “and chief of the desert, ye have no men to waste. Soon ye will need all the swords ye have and they may not suffice. You are in a trap.”

Ali tugged at his beard and his eyes were evil and fearful.

“If ye be a true man, tell me whose host is that upon the plain.”

“That is the army of Muhammad Khan, sultan of Kizilshehr.”

Those about Ali cried out mockingly and angrily and Ali cursed.

“You lie! Muhammad’s wolves have harried us for a day and a night. They have hung at our flanks like jackals dogging a wounded stag. At dusk we turned on them and scattered them; then when we rode into the hills, lo, on the other side we saw a great host encamped. How can that be Muhammad?”

“Those who harried you were no more than outriders,” replied Sir Eric, “light cavalry sent by Muhammad to hang on your flanks and herd you into his trap like so many cattle. The country is up behind you; you cannot turn back. Nay, the only way is through the Persian ranks.”

“Aye, so,” said Ali with bitter irony. “Now I know you speak like a friend; shall five hundred men cut their way through ten thousand?”

Sir Eric laughed. “The mists of morning still veil yon plain. Let them rise and you will see no more than a thousand men.”

“He lies,” broke in Yurzed, for whom I was beginning to cherish a hearty dislike. “All night the plain was full of the tramp of horsemen and we saw the blaze of a hundred fires.”

“To trick you,” said Sir Eric, “to make you believe you looked on a great army. The horsemen rode the plain, partly to create the impression of vast numbers, partly to prevent scouts from slipping too close to the fires. You have to deal with a master at stratagems. When did you come into these hills?”

“Somewhat after dark, last night,” said Ali.

“And Muhammad arrived at dusk. Did you not see the signal smokes behind and about you as you rode? They were lighted by scouts to reveal to Muhammad your movements. He timed his march perfectly and arrived in time to build his fires and catch you in his trap. You might have ridden through them last night, and many escaped. Now you must fight by daylight and I have no doubt but that more Persians are riding this way. See, the mist clears; come with me to yon eminence and I will show you I speak truth.”

The mist indeed had cleared from the plain, and Ali cursed as he looked down on the wide flung camp of the Persians, who were beginning to tighten cinch and armor strap, and see to their weapons, judging from the turmoil in camp.

“Trapped and tricked,” he cursed. “And my own men growl behind my back. There is no water nor much grass in these hills. So close those cursed Kurds pressed us, that we, who thought them the vanguard of Muhammad’s army, have had no time to rest or eat for a day and a night. We have not even built fires for lack of aught to cook. What of the five hundred outriders we scattered at dusk, Sir Eric? They fled at the first charge, the crafty dogs.”

“No doubt they have reformed and lurk somewhere in your rear,” said Sir Eric. “Best that we mount and strike the Persians swiftly, before the heat of the growing day weakens your hungry men. If those Kurds come in behind us, we are caught in the nut cracker.”

Ali nodded and gnawed his beard, as one lost in deep thought. Suddenly he spake: “Why do you tell me this? Why join yourselves to the weaker side? What guile brought you into my camp?”

Sir Eric shrugged his shoulders. “We are fleeing Muhammad. This girl is my betrothed, whom one of his emirs stole from me. If they catch us, our lives are forfeit.”

Thus he spake, not daring to divulge the fact that it was Muhammad himself who desired the girl, nor that she was the niece of William de Brose, lest Ali buy peace from the Persian by handing us over to him.

The Arab nodded absently, but he seemed well pleased. “Give them back their swords,” said he, “I have heard that Sir Eric de Cogan keeps his word. We will take the Turk on trust.”

So Yurzed reluctantly gave us back our blades. Sir Eric’s weapon was a true Crusader’s sword—long, heavy and double edged with a wide cross guard. Mine was a scimitar forged beyond the Oxus—the hilt set in jewels, the blade of fine blue steel of goodly length, not too curved for thrusting nor too straight for slashing, not too heavy for swift and cunning work yet not too light for mighty blows.

Sir Eric drew the girl aside and said softly: “Ettaire, God knows what is best. It may be that you and I and Kosru Malik die here.We must fight the Persians and God alone knows what the outcome may be. But any other course had cut our throats.”

“Come what may, my dear lord,” said she with her soul shining in her eyes, “if it find me by your side, I am content.”

“What manner of warriors are these Bedoui, my brother?” asked Sir Eric.

“They are fierce fighters,” I answered, “but they will not stand. One of them in single combat is a match for a Turk and more than a match for a Kurd or a Persian, but the melee of a serried field is another matter. They will charge like a blinding blast from the desert and if the Persians break and the smell of victory touches the Arabs’ nostrils, they will be irresistible. But if Muhammad holds firm and withstands their first onslaught, then you and I had better break away and ride, for these men are hawks who give over if they miss their prey at the first swoop.”

“But will the Persians stand?” asked Sir Eric.

“My brother,” said I, “I have no love for these Irani. They are called cowards, sometimes; but a Persian will fight like a blood-maddened devil when he trusts his leader. Too many false chiefs have disgraced the ranks of Persia. Who wishes to die for a sultan who betrays his men? The Persians will stand; they trust Muhammad and there are many Turks and Kurds to stiffen the ranks. We must strike them hard and shear straight through.”

The hawks were gathering from the hills, assembling in the basin and saddling their steeds. Ali bin Sulieman came striding over to where we sat and stood glowering down at us. “What thing do ye discuss amongst yourselves?”

Sir Eric rose, meeting the Arab eye to eye. “This girl is my betrothed, stolen from me by Muhammad’s men, and stolen back again by me, as I told you. Now I am hard put to find a place of safety for her. We cannot leave her in the hills; we cannot take her with us when we ride down into the plains.”

Ali looked at the girl as if he had seen her for the first time, and I saw lust for her born in his eyes. Aye, her white face was a spark to fire men’s hearts.

“Dress her as a boy,” he suggested. “I will put a warrior to guard her, and give her a horse. When we charge, she shall ride in the rear ranks, falling behind. When we engage the Irani, let her ride like the wind and circle the Persian camp if she may, and flee southward—toward Araby. If she is swift and bold she may win free, and her guard will cut down any stragglers who may seek to stop her. But with the whole Iranian host engaged with us, it is not likely that two horsemen fleeing the battle will be noticed.”

Ettaire turned white when this was explained to her, and Sir Eric shuddered. It was indeed a desperate chance, but the only one. Sir Eric asked that I be allowed to be her guard, but Ali answered that he could spare another man better—doubtless he distrusted me, even if he trusted Sir Eric, and feared I might steal the girl for myself. He would agree to naught else, but that we both ride at his side, and we could but agree. As for me, I was glad; I, a hawk of the Chagatai, to be a woman’s watch-dog when a battle was forward! A youth named Yussef was detailed for the duty and Ali gave the girl a fine black mare. Clad in Arabian garments, she did in sooth look like a slim young Arab, and Ali’s eyes burned as he looked on her. I knew that did we break through the Persians, we would still have the Arab to fight if we kept the girl.

The Bedouins were mounted and restless. Sir Eric kissed Ettaire, who wept and clung to him, then he saw that she was placed well behind the last rank, with Yussef at her side, and he and I took our places beside Ali bin Sulieman. We trotted swiftly through the ravines and debouched upon the broken hillsides.

There is no God but God! With the early morning sun blazing on the eastern hills we thundered down the defiles and swept out on to the plain where the Persian army had just formed. By Allah, I will remember that charge when I lie dying! We rode like men who ride to feast with Death, with our blades in hands and the wind in our teeth and the reins flying free.

And like a blast from Hell we smote the Persian ranks which reeled to the shock. Our howling fiends slashed and hacked like madmen and the Kizilshehri went down before them like garnered grain. Their saber-play was too swift and desperate for the eye to follow—like the flickering of summer lightning. I swear that a hundred Persians died in the instant of impact when the lines met and our flying squadron hacked straight into the heart of the Persian host. There the ranks stiffened and held, though sorely beset, and the clash of steel rose to the skies. We had lost sight of Ettaire and there was no time to look for her; her fate lay in the lap of Allah.

I saw Muhammad Khan sitting his great white stallion in the midst of his emirs as coolly as if he watched a parade—yet the flickering blades of our screaming devils were a scant spear-cast from him. His lords thronged about him—Kai Kedra, the Seljuk, Abdullah Bey, Mirza Khan, Dost Said, Mechmet Atabeg, Ahmed El Ghor, himself an Arab, and Yar Akbar, a hairy giant of a renegade Afghan, accounted the strongest man in Kizilshehr.

Sir Eric and I hewed our way through the lines, shoulder to shoulder, and I swear by the Prophet, we left only empty saddles behind us. Aye, our steeds’ hoofs trod headless corpses! Yet somehow Ali bin Sulieman won through to the emirs before us. Yurzed was close at his heels, but Mirza Khan cut off his head with a single stroke and the emirs closed about Ali bin Sulieman who yelled like a blood-mad panther and stood up in his stirrups, smiting like a madman.

Three Persian men-at-arms he slew, and he dealt Mirza Khan such a blow that it stunned and unhorsed him, though his helmet saved the Persian’s brain. Abdullah Bey reined in from behind and thrust his scimitar point through the Arab’s mail and deep into his back, and Ali reeled, but ceased not to ply his long saber.

By this time Sir Eric and I had hacked a way to his side. Sir Eric rose in his saddle and shouting the Frankish war-cry, dealt Abdullah Bey such a stroke that helmet and skull shattered together and the emir went headlong from his saddle. Ali bin Sulieman laughed fiercely and though at this instant Dost Said hewed through mail-shirt and shoulder-bone, he spurred his steed headlong into the press. The great horse screamed and reared, and leaning downward, Ali sheared through the neck cords of Dost Said, and lunged at Muhammad Khan through the melee. But he overreached as he struck and Kai Kedra gave him his death stroke.

A great cry went up from the hosts, Arabs and Persians, who had seen the deed, and I felt the whole Arabian line give and slacken. I thought it was because Ali bin Sulieman had fallen, but then I heard a great shouting on the flanks and above the din of carnage, the drum of galloping hoofs. Mechmet Atabeg was pressing me close and I had no time to snatch a glance. But I felt the Arab lines melting and crumbling away, and mad to see what was forward, I took a desperate chance, matching my quickness against the quickness of Mechmet Atabeg and killed him. Then I chanced a swift look. From the north, down from the hills we had just quitted thundered a squadron of hawk-faced men—the Kurds that had been following the Roualli.

At that sight the Arabs broke and scattered like a flight of birds. It was every man for himself and the Persians cut them down as they ran. In a trice the battle changed from a close locked struggle to a loose maze of flight and single combats that streamed out over the plain. Our charge had carried Sir Eric and me deep into the heart of the Persian host. Now when the Kizilshehrians broke away to pursue their foes, it left but a thin line between us and the open desert to the south.

We struck in the spurs and burst through. Far ahead of us we saw two horsemen riding hard, and one rode the tall black mare the Arabs had given Ettaire. She and her guard had won through, but the plain was alive with horsemen who flew and horsemen who pursued.

We fled after Ettaire and as we swept past the group that guarded Muhammad Khan, we came so close that I saw the boldness and fearlessness of his brown eyes. Aye—there I looked on the face of a born king.

Men opposed us and men pursued us, but they who followed were left behind and they who barred our way died. Nay, the slayers soon turned to easier prey—the flying Arabs.

So we passed over the battle-strewn plain and we saw Ettaire rein in her mount and gaze back toward the field of battle, while Yussef strove to urge her on. But she must have seen us, for she threw up her arm—and then a band of Kurds swept down on them from the side—camp-followers, jackals who followed Muhammad for loot. We heard a scream and saw the swift flicker of steel, and Sir Eric groaned and rowelled his steed until it screamed and leaped madly ahead of my bay, and we swept up on the struggling group.

The Arab Yussef had wrought well; from one Kurd had he struck off the left arm at the shoulder, and he had broken his scimitar in the breast of another. Now as we rode up his horse went down, but as he fell, the Arab dragged a Kurd out of the saddle and rolling about on the ground, they butchered each other with their curved daggers.

The other Kurds, by some chance, had pulled Ettaire down, instead of slashing off her head, thinking her to be a boy. Now as they tore her garments and exposed her face in their roughness, they saw she was a girl and fair, and they howled like wolves. And as they howled, we smote them.

By the Prophet, a madness was over Sir Eric; his eyes blazed terribly from a face white as death, and his strength was beyond that of mortal man. Three Kurds he slew with three blows and the rest cried out and gave way, screaming that a devil was among them. And in fleeing one passed too near me and I cut off his head to teach him manners.

And now Sir Eric was off his horse and had gathered the terrified girl in his arms, while I looked to Yussef and the Kurd and found them both dead. And I discovered another thing—I had a lance thrust in my thigh, and how or when I received it, I know not for the fire of battle makes men insensible to wounds. I staunched the blood and bound it up as best I could with strips torn from my garments.

“Haste in the name of Allah!” said I to Sir Eric with some irritation, as it seemed he would fondle the girl and whisper pet names to her all morning. “We may be set upon any moment. Set the woman on her horse and let us begone. Save your love-making for a more opportune time.”

“Kosru Malik,” said Sir Eric, as he did as I advised, “you are a firm friend and a mighty fighter, but have you ever loved?”

“A thousand times,” said I. “I have been true to half the women in Samarcand. Mount, in God’s name, and let us ride!”

I gasped, “A kingdom waits my lord, her love is but her own,

A day shall mar, a day shall cure for her, but what of thee?

Cut loose the girl—he follows fast—cut loose and ride alone!”

Then Scindhia ’twixt his blistered lips: “My queens’ queen shall she be!”

—Kipling

And so we rode out of that shambles and to avoid any stray bands of pillagers—for all the countryside rises when a battle is fought and they care not whom they rob—we rode south and a little east, intending to swing back toward westward when we had put a goodly number of leagues between us and the victorious Kizilshehri.

We rode until past the noon hour when we found a spring and halted there to rest the horses and to drink. A little grass grew there but of food for ourselves we had none and neither Sir Eric nor I had eaten since the day before, nor slept in two nights. But we dared not sleep with the hawks of war on the wing and none too far away, though Sir Eric made the girl lie down in the shade of a straggling tamarisk and snatch a small nap.

An hour’s rest and we rode on again, slowly, to save the horses. Again, as the sun slanted westward we paused awhile in the shade of some huge rocks and rested again, and this time Sir Eric and I took turn at sleeping, and though neither of us slept over half an hour, it refreshed us marvellously. Again we took up the trail, swinging in a wide arc to westward.

It was almost nightfall when I began to realize the madness that had fallen on Muhammad Khan. There came to me the strange restless feeling all desert-bred men know—the sensation of pursuit. Dismounting I laid my ear to the ground. Aye, many horsemen were riding hard, though still far away. I told Sir Eric and we hastened our pace, thinking it perhaps a band of fleeing Arabs.

We swung back to the east again, to avoid them, but when dusk had fallen, I listened to the ground again and again caught the faint vibration of many hoofs.

“Many riders,” I muttered. “By Allah, Sir Eric, we are being hunted.”

“Is it us they pursue?” asked Sir Eric.

“Who else?” I made answer. “They follow our trail as hunting-dogs follow a wounded wolf. Sir Eric, Muhammad is mad. He lusts after the maid, fool that he is, to thus risk throwing away an empire for a puling girl-child. Sir Eric, women are more plentiful than sparrows, but warriors like thyself are few. Let Muhammad have the girl. ’Twere no disgrace—a whole army hunts us.”

His jaw set like iron and he said only: “Ride away and save thyself.”

“By the blood of Allah,” said I softly, “none but thou could use those words to me and live.”

He shook his head. “I meant no insult by them, my brother; no need for thou too to die.”

“Spur up the horses, in God’s name,” I said wearily. “All Franks are mad.”

And so we rode on through the gathering twilight, into the light of the stars, and all the while far behind us vibrated the faint but steady drum of many hoofs. Muhammad had settled to a steady grinding gait, I believed, and I knew he would gain slowly on us for his steeds were the less weary. How he learned of our flight, I never knew. Perhaps the Kurds who escaped Sir Eric’s fury brought him word of us; perhaps a tortured Arab told him.

Thinking to elude him, we swung far to the east and just before dawn I no longer caught the vibration of the hoofs. But I knew our respite was short; he had lost our trail but he had Kurds in his ranks who could track a wolf across bare rocks. Muhammad would have us ere another sun set.

At dawn we topped a rise and saw before us, spreading to the sky-line, the calm waters of the Green Sea—the Persian Gulf. Our steeds were done; they staggered and tossed their heads, legs wide braced. In the light of dawn I saw my comrades’ drawn and haggard faces. The girl’s eyes were shadowed and she reeled with weariness though she spoke no word of complaint. As for me, with a single half hour’s sleep for three nights, all seemed dim and like a dream at times till I shook myself into wakefulness. But Sir Eric was iron, brain and spirit and body. An inner fire drove him and spurred him on, and his soul blazed so brightly that it overcame the weakness and weariness of his body. Aye, but it is a hard road, the road of Azrael!

We came upon the shores of the sea, leading our stumbling mounts. On the Arab side the shores of the Green Sea are level and sandy, but on the Persian side they are high and rocky. Many broken boulders lined the steep shores so that the steeds had much ado to pick their way among them.

Sir Eric found a nook between two great boulders and bade the girl sleep a little, while I remained by her to keep watch. He himself would go along the shore and see if he might find a fisher’s boat, for it was his intention that we should go out on the face of the sea in an effort to escape the Persians. He strode away among the rocks, straight and tall and very gallant in appearance, with the early light glinting on his armor.

The girl slept the sleep of utter exhaustion and I sat nearby with my scimitar across my knees, and pondered the madness of Franks and Sultans. My leg was sore and stiff from the spear thrust, I was athirst and dizzy for sleep and from hunger, and saw naught but death for all ahead.

At last I found myself sinking into slumber in spite of myself, so, the girl being fast asleep, I rose and limped about, that the pain of my wound might keep me awake. I made my way about a shoulder of the cliff a short distance away—and a strange thing came suddenly to pass.

One moment I was alone among the rocks, the next instant a huge warrior had leaped from behind them. I knew in a flashing instant that he was some sort of a Frank, for his eyes were light and they blazed like a tiger’s, and his skin was very white, while from under his helmet flowed flaxen locks. Flaxen, likewise, was his thick beard, and from his helmet branched the horns of a bull so at first glance I thought him some fantastic demon of the wilderness.

All this I perceived in an instant as with a deafening roar, the giant rushed upon me, swinging a heavy, flaring edged axe in his right hand. I should have leaped aside, smiting as he missed, as I had done against a hundred Franks before. But the fog of half-sleep was on me and my wounded leg was stiff.

I caught his swinging axe on my buckler and my forearm snapped like a twig. The force of that terrific stroke dashed me earthward, but I caught myself on one knee and thrust upward, just as the Frank loomed above me. My scimitar point caught him beneath the beard and rent his jugular; yet even so, staggering drunkenly and spurting blood, he gripped his axe with both hands, and with legs wide braced, heaved the axe high above his head. But life went from him ere he could strike.

Then as I rose, fully awake now from the pain of my broken arm, men came from the rocks on all sides and made a ring of gleaming steel about me. Such men I had never seen. Like him I had slain, they were tall and massive with red or yellow hair and beards and fierce light eyes. But they were not clad in mail from head to foot like the Crusaders. They wore horned helmets and shirts of scale mail which came almost to their knees but left their throats and arms bare, and most of them wore no other armor at all. They held on their left arms heavy kite shaped shields, and in their right hands wide edged axes. Many wore heavy golden armlets, and chains of gold about their necks.

Surely such men had never before trod the sands of the East. There stood before them, as a chief stands, a very tall Frank whose hauberk was of silvered scales. His helmet was wrought with rare skill and instead of an axe he bore a long heavy sword in a richly worked sheath. His face was as a man that dreams, but his strange light eyes were wayward as the gleams of the sea.

Beside him stood another, stranger than he; this man was very old, with a wild white beard and white elf locks. Yet his giant frame was unbowed and his thews were as oak and iron. Only one eye he had and it held a strange gleam, scarcely human. Aye, he seemed to reckon little of what went about him, for his lion-like head was lifted and his strange eye stared through and beyond that on which it rested, into the deeps of the world’s horizons.

Now I saw that the end of the road was come for me. I flung down my scimitar and folded my arms.

“God gives,” said I, and waited for the stroke.

And then there sounded a swift clank of armor and the warriors whirled as Sir Eric burst roughly through the ring and faced them. Thereat a sullen roar went up and they pressed forward. I caught up my scimitar to stand at Sir Eric’s back, but the tall Frank in the silvered mail raised his hand and spoke in a strange tongue, whereat all fell silent. Sir Eric answered in his own tongue: “I cannot understand Norse. Can any of you speak English or Norman-French?”

“Aye,” answered the tall Frank whose height was half a head more than Sir Eric’s. “I am Skel Thorwald’s son, of Norway, and these are my wolves. This Saracen has slain one of my carles. Is he your friend?”

“Friend and brother-at-arms,” said Sir Eric. “If he slew, he had just reason.”

“He sprang on me like a tiger from ambush,” said I wearily. “They are your breed, brother. Let them take my head if they will; blood must pay for blood. Then they will save you and the girl from Muhammad.”

“Am I a dog?” growled Sir Eric, and to the warriors he said: “Look at your wolf; think you he struck a blow after his throat was cut? Yet here is Kosru Malik with a broken arm. Your wolf smote first; a man may defend his life.”

“Take him then, and go your ways,” said Skel Thorwald’s son slowly. “We would not take an unfair advantage of the odds, but I like not your pagan.”

“Wait!” exclaimed Sir Eric, “I ask your aid! We are hunted by a Moslem lord as wolves hunt deer. He seeks to drag a Christian girl into his harem—”

“Christian!” rumbled Skel Thorwald’s son. “But ten days agone I slew a horse to Thor.”

I saw a slow desperation grow in Sir Eric’s deep-lined face.

“I thought even you Norse had forsaken your pagan gods,” said he. “But let it rest—if there be manhood among ye, aid us, not for my sake nor the sake of my friend, but for the sake of the girl who sleeps among these rocks.”

At that from among the rest thrust himself a warrior my height and of mighty build. More than fifty winters he had known, yet his red hair and beard were untouched by grey, and his blue eyes blazed as if a constant rage flamed in his soul.

“Aye!” he snarled. “Aid ye ask, you Norman dog! You, whose breed overran the heritage of my people—whose kinsmen rode fetlock deep in good Saxon blood—now you howl for aid and succor like a trapped jackal in this naked land. I will see you in Hell before I lift axe to defend you or yours.”

“Nay, Hrothgar,” the ancient white bearded giant spoke for the first time and his voice was like the call of a deep throated trumpet. “This knight is alone among we many. Entreat him not harshly.”

Hrothgar seemed abashed, angry, yet wishful to please the old one.

“Aye, my king,” he muttered half sullenly, half apologetically.

Sir Eric started: “King?”

“Aye!” Hrothgar’s eyes blazed anew; in truth he was a man of constant spleen. “Aye—the monarch your cursed William tricked and trapped, and beat by a trick to cast from his throne. There stands Harold, the son of Godwin, rightful king of England!”

Sir Eric doffed his helmet, staring as if at a ghost.

“But I do not understand,” he stammered. “Harold fell at Senlac—Edith Swan-necked found him among the slain—”

Hrothgar snarled like a wounded wolf, while his eyes flamed and flickered with blue lights of hate.

“A trick to cozen tricksters,” he snarled. “That was an unknown chief of the west Edith showed to the priests. I, a lad of ten, was among those that bore King Harold from the field by night, senseless and blinded.”

His fierce eyes grew gentler and his rough voice strangely soft.

“We bore him beyond the reach of the dog William and for months he lay nigh unto death. But he lived, though the Norman arrow had taken his eye and a sword-slash across the head had left him strange and fey.”

Again the lights of fury flickered in the eyes of Hrothgar.

“Forty-three years of wandering and harrying on the Viking path!” he rasped. “William robbed the king of his kingdom, but not of men who would follow and die for him. See ye these Vikings of Skel Thorwald’s son? Northmen, Danes, Saxons who would not bide under the Norman heel—we are Harold’s kingdom! And you, you French dog, beg us for aid! Ha!”

“I was born in England—” began Sir Eric.

“Aye,” sneered Hrothgar, “under the roof of a castle wrested from some good Saxon thane and given to a Norman thief!”

“But kin of mine fought at Senlac beneath the Golden Dragon as well as on William’s side,” protested Sir Eric. “On the distaff side I am of the blood of Godric, earl of Wessex—”

“The more shame to you, renegade mongrel,” raved the Saxon. “I—”

The swift patter of small feet sounded on the rocks. The girl had wakened, and frightened by the rough voices, had come seeking her lover. She slipped through the mailed ranks and ran into Sir Eric’s arms, panting and staring wildly about in terror at the grim slayers. The Northmen fell silent.

Sir Eric turned beseechingly toward them: “You would not let a child of your own breed fall into the hands of the pagans? Muhammad Khan, sultan of Kizilshehr is close on our heels—scarce an hour’s ride away. Let us go into your galley and sail away with you—”

“We have no galley,” said Skel Thorwald’s son. “In the night we ventured too close inshore and a hidden reef ripped the guts out her. I warned Asgrimm Raven that no good would come of sailing out of the broad ocean into this narrow sea, which witches make green fire at night—”

“And what could we, a scant hundred, do against a host?” broke in Hrothgar, “We could not aid you if we would—”

“But you too are in peril,” said Sir Eric. “Muhammad will ride you down. He has no love for Franks.”

“We will buy our peace by delivering to him you and the girl and the Turk, bound hand and foot,” replied Hrothgar. “Asgrimm Raven cannot be far away; we lost him in the night but he will be scouring the coast to find us. We had not dared light a signal fire lest the Saracens see it. But now we will buy peace of this Eastern lord—”

“Peace!” Harold’s voice was like the deep mellow call of a great golden bell. “Have done, Hrothgar. That was not well said.”

He approached Sir Eric and the girl and they would have knelt before him, but he prevented it and lightly laid his corded hand on Ettaire’s head, tilting gently back her face so that her great pleading eyes looked up at him. And I called on the Prophet beneath my breath for the ancient one seemed unearthly with his great height and the strange mystic gleam of his eye, and his white locks like a cloud about his mailed shoulders.

“Such eyes had Editha,” said he softly. “Aye, child, your face bears me back half a century. You shall not fall into the hands of the heathen while the last Saxon king can lift a sword. I have drawn my blade in many a less worthy brawl on the red roads I have walked. I will draw it again, little one.”

“This is madness!” cried out Hrothgar. “Shall kites pick the bones of Godwin’s son because of a French girl?”

“God’s splendor!” thundered the ancient. “Am I king or dog?”

“You are king, my liege,” sullenly growled Hrothgar, dropping his eyes. “It is yours to give command—even in madness we follow.”

Such is the devotion of savage men!

“Light the beacon-fire, Skel Thorwald’s son,” said Harold. “We will hold the Moslem hard till the coming of Asgrimm Raven, God willing. What are thy names, thine and this warrior of the East?”

Sir Eric told him, and Harold gave orders. And I was amazed to see them obeyed without question. Skel Thorwald’s son was chief of these men, but he seemed to grant Harold the due of a veritable monarch—he whose kingdom was lost and dead in the mists of time.

Sir Eric and Harold set my arm, binding it close to my body. Then the Vikings brought food and a barrel of stuff they called ale, which had been washed ashore from the broken ship, and while we watched the signal smoke go up, we ate and drank ravenously. And new vigor entered into Sir Eric. His face was drawn and haggard from lack of sleep and the strain of flight and battle, but his eyes blazed with indomitable light.

“We have scant time to arrange our battle-lines, your majesty,” said he, and the old king nodded.

“We cannot meet them in this open place. They would league us on all sides and ride us down. But I noted a very broken space not far from here—”

So we went to this place. A Viking had found a hollow in the rocks where water had gathered, and we gave the weary horses to drink and left them there, drooping in the shade of the cliffs. Sir Eric helped the girl along and would have given me a hand but I shook my head as I limped along. And Hrothgar came and slipped his mighty arm beneath my shoulders and so aided me, for my wounded leg was numb and stiff.

“A mad game, Turk,” he growled.

“Aye,” I answered as one in a dream. “We be all madmen and ghosts on the Road of Azrael. Many have died for the yellow-haired girl. More will die ere the road is at an end. Much madness have I seen in the days of my life, but never aught to equal this.”

We shall not see the hills again where the grey cloud limns the oak,

We who die in a naked land to succor an alien folk;

Well—we have followed the Viking-path with a king to lead us forth—

And scalds will thunder our victories in the washael halls of the North.

—The Song of Skel Thorwald’s Son

Already the drum of many hoofs was in our ears. We took our stand in a wide cleft of a cliff, with the broken, boulder strewn beach at our backs. The land in front of us was a ravine-torn waste, over which the horses could not charge. The Franks massed themselves in the wide cleft, shoulder to shoulder, wide shields overlapping. At the tip of this shield-wall stood King Harold with Skel Thorwald’s son on one hand and Hrothgar on the other.

Sir Eric had found a sort of ledge in the cliff behind and above the heads of the warriors, and here he placed the girl.

“You must bide with her, Kosru Malik,” said he. “Your arm is broken, your leg stiff; you are not fit to stand in the shield-wall.”

“God gives,” said I. “But my heart is heavy and the tang of bitterness is in my mouth. I had thought to fall beside you, my brother.”

“I give her in your trust,” said he, and clasping the girl to him, he held her hungrily a moment, then dropped from the ledge and strode away, while she wept and held out her white arms after him.

I drew my scimitar and laid it across my knees. Muhammad might win the fight, but when he came to take the girl he would find only a headless corpse. She should not fall into his hands alive.

Aye, I gazed on that slim white bit of flesh and swore in wonder and amaze that a frail woman could be the death of so many strong men. Verily, the star of Azrael hovers over the birth of a beautiful woman, the King of the Dead laughs aloud and ravens whet their black beaks.

She was brave enough. She ceased her whimpering soon and made shift to cleanse and rebandage my wounded leg, for which I thanked her. And while so occupied there was a thunder of hoofs and Muhammad Khan was upon us. The riders numbered at least five hundred men, perhaps more, and their horses reeled with weariness. They drew rein at the beginning of the broken ground and gazed curiously at the silent band in the defile. I saw Muhammad Khan, slender, tall, with the heron feathers in his gilded helmet. And I saw Kai Kedra, Mirza Khan, Yar Akbar, Ahmed El Ghor the Arab, and Kojar Khan, the great emir of the Kurds, he who had led the riders who harried the Arabs.

Now Muhammad stood up in his golden stirrups and shading his eyes with his hand, turned and spoke to his emirs, and I knew he had recognized Sir Eric beside King Harold. Kai Kedra reined his steed forward through the broken gullies as far as it could go, and making a trumpet of his hands, called aloud in the tongue of the Crusaders: “Harken, Franks, Muhammad Khan, sultan of Kizilshehr, has no quarrel with you; but there stands one who has stolen a woman from the sultan; therefore, give her up to us and ye may depart peacefully.”

“Tell Muhammad,” answered Sir Eric, “that while one Frank lives, he shall not have Ettaire de Brose.”

So Kai Kedra rode back to Muhammad who sate his horse like a carven image, and the Persians conferred among themselves. And I wondered again. But yesterday Muhammad Khan had fought a fierce battle and destroyed his foes; now he should be riding in triumph down the broad streets of Kizilshehr, with crimson standards flying and golden trumpets blaring, and white-armed women flinging roses before his horse’s hoofs; yet here he was, far from his city, and far from the field of battle, with the dust and weariness of hard riding on him, and all for a slender girl-child.

Aye—Muhammad’s lust and Sir Eric’s love were whirlpools that drew in all about them. Muhammad’s warriors followed him because it was his will; King Harold opposed him because of the strangeness in his brain and the mad humor Franks call chivalry; Hrothgar who hated Sir Eric, fought beside him because he loved Harold, as did Skel Thorwald’s son and his Vikings. And I, because Sir Eric was my brother-at-arms.

Now we saw the Persians dismounting, for they saw there was no charging on their weary horses over that ground. They came clambering over the gullies and boulders in their gilded armor and feathered helmets, with their silver-chased blades in their hands. Fighting on foot they hated, yet they came on, and the emirs and Muhammad himself with them. Aye, as I saw the sultan striding forward with his men, my heart warmed to him again and I wished that Sir Eric and I were fighting for him, and not against him.

I thought the Franks would assail the Persians as they clamored across the ravines but the Vikings did not move out of their tracks. They made their foes come to them, and the Moslems came with a swift rush across the level space and a shouting of, “Allaho akbar!”

That charge broke on the shield-wall as a river breaks on a shoal. Through the howling of the Persians thundered the deep rhythmic shouts of the Vikings and the crashing of the axes drowned the singing and whistling of the scimitars.

The Norsemen were immovable as a rock. After that first rush the Persians fell back, baffled, leaving a crescent of hacked corpses before the feet of the blond giants. Many strung bows and drove in their arrows at short range but the Vikings merely bent their heads and the shafts glanced from their horned helmets or shivered on the great shields.

And the Kizilshehrians came on again. Watching above, with the trembling girl beside me, I burned and froze with the desperate splendor of that battle. I gripped my scimitar hilt until blood oozed from beneath my finger nails. Again and again Muhammad’s warriors flung themselves with mad valor against the solid iron wall. And again and again they fell back broken. Dead men were heaped high and over their mangled bodies the living climbed to hack and smite.

Franks fell too, but their comrades trampled them under and closed the ranks again. There was no respite; ever Muhammad urged on his warriors, and ever he fought on foot with them, his emirs at his side. Allaho akbar! There fought a man and a king who was more than a king!

I had thought the Crusaders mighty fighters, but never had I seen such warriors as these, who never tired, whose light eyes blazed with strange madness, and who chanted wild songs as they smote. Aye, they dealt great blows! I saw Skel Thorwald’s son hew a Kurd through the hips so the legs fell one way and the torso another. I saw King Harold deal a Turk such a blow that the head flew ten paces from the body. I saw Hrothgar hew off a Persian’s leg at the thigh, though the limb was cased in heavy mail.

Yet they were no more terrible in battle than my brother-at-arms, Sir Eric. I swear, his sword was a wind of death and no man could stand before it. His face was lighted strangely and mystically; his arm was thrilled with superhuman strength, and though I sensed a certain kinship between himself and the wild barbarians who chanted and smote beside him, yet a mystic, soul-something set him apart from and beyond them. Aye, the forge of hardship and suffering had burned from soul and brain and body all dross and left only the white hot fire of his inner soul that lifted him to heights unattainable by common men.

On and on the battle raged. Many Moslems had fallen, but many Vikings had died too. The remnant had been slowly hurled back by repeated charges until they were battling on the beach almost beneath the ledge whereon I stood with the girl. There the formation was broken among the boulders and the conflict changed to a straggling series of single conflicts. The Norsemen had taken fearful toll—by Allah, no more than a hundred Persians remained able to lift the sword! And of Franks there were less than a score.

Skel Thorwald’s son and Yar Akbar met face to face just as the Viking’s notched sword broke in a Moslem’s skull. Yar Akbar shouted and swung up his scimitar but ere he could strike, the Viking roared and leaped like a great lion. His iron arms locked about the huge Afghan’s body and I swear I heard above the battle, the splintering of Yar Akbar’s bones. Then Skel Thorwald’s son dashed him down, broken and dead, and catching up an axe from a dying hand, made at Muhammad Khan. Kai Kedra was before him. Even as the Viking struck, the Seljuk drove his scimitar through mail links and ribs and the two fell together.