Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

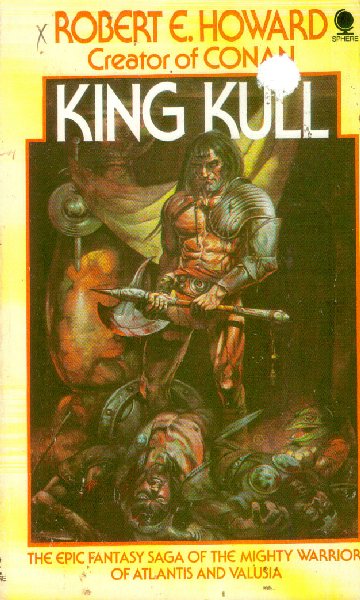

Untitled fragment first published in Kull, 1978. (Cover below is from King Kull, 1976, which Kull was a reissue of.)

Completed and named by Lin Carter.

“Thus,” said Tu, chief councilor, “did Lala-ah, countess of Fanara, flee with her lover, Fenar, Farsunian adventurer, bringing shame to her husband-to-be and to the nation of Valusia.”

Kull, fist supporting chin, nodded. He had listened with scant interest to the tale of how the young countess of Fanara had left a Valusian nobleman waiting on the steps of Merama’s and had eloped with a man of her own choice.

“Yes,” he impatiently interrupted Tu, “I understand. But what have the amorous adventures of a giddy girl to do with me? I blame her not for forsaking Ka-yanna—by Valka, he is as ugly as a rhinoceros and has a more abominable disposition. Then why tell me this tale?”

“You do not understand, Kull,” said Tu, with the patience one must accord a barbarian who happens to be a king, besides. “The customs of the nation are not your customs. Lala-ah, by deserting Ka-yanna at the very foot of the altar where their nuptials were to be consummated, committed a very gross offense to the traditions of the land—and an insult to the nation is an insult to the king, Kull. For this alone she must be brought back and punished.

“Then, she is a countess, and it is a Valusian tradition that noble women marry foreigners only with the consent of the Valusian state—here consent was never given nor even asked. Valusia will become the scorn of all nations if we allow men from other lands to take our women with impunity.”

“Name of Valka,” grumbled Kull. “Here is a great to-do— custom and tradition! I have heard little else since I first pressed the throne of Valusia. In my land women mate with whom they will and with whom they choose.”

“Aye, Kull,” thus Tu, soothingly. “But this is Valusia—not Atlantis. There all men, aye, and all women, are free and unhindered, but civilization is a network and a maze of precedences and custom. And another thing in regard to the young countess: she has a strain of royal blood.

“This man rode with Ka-yanna’s horsemen in pursuit of the girl,” said Tu.

“Aye,” the young man spoke, “and I have for you a word from Fenar, lord king.”

“A word for me? I never saw Fenar.”

“Nay, but this he said to a border guard of Zarfhaana, to be repeated to they who pursued; ‘Tell the barbarian swine who defiles an ancient throne that I name him scoundrel. Tell him that some day I shall return and clothe his cowardly carcass in the clothing of women, to attend my chariot horses.’ ”

Kull’s vast bulk heaved erect, his chair of state crashing to the floor. A moment he stood, speechless, then he found voice in a roar that sent Tu and the noble backward.

“Valka, Honen, Holgar, and Hotath!” he roared, mingling deities with heathen gods in a manner that made Tu’s hair rise at the blasphemy. Kull’s huge arms were brandished aloft and his mighty fist descended on the tabletop with a force that buckled the heavy legs like paper. Tu, pale, swept off his feet by this tide of barbarian fury, backed against the wall, followed by the young noble who had dared much in giving Fenar’s word. However, Kull was too much the savage to connect the insult with the bearer; it must remain for civilized rulers to wreak vengeance on couriers.

“Horses!” roared Kull. “Have the Red Slayers mount! Send Brule to me!”

He tore off his kingly robe and hurled it across the room, snatched a costly vase from the broken table and dashed it to the floor.

“Hurry!” gasped Tu, shoving the young nobleman toward the door. “Get Brule, the Pictish Spear-slayer—haste, before he slays us all!”

Tu judged the king’s actions by those of preceding kings; however, Kull had not progressed far enough in civilized custom to wreak his royal rage on innocent subjects.

His first red fury had been succeeded by a cold steel rage by the time Brule arrived. The Pict stalked in unconcernedly, a grim smile touching his lips as he marked the destruction caused by the king’s wrath. Kull was garbing himself in riding garments and he looked up as Brule entered, his scintillant gray eyes gleaming coldly.

“Kull, we ride?” asked the Pict.

“Aye, we ride hard and far, by Valka! We ride to Zarfhaana first and perhaps beyond—to the lands of the snow or the desert sands or to Hell! Have three hundred of the Red Slayers in readiness.”

Brule grinned in pure enjoyment. He was a powerfully built man of medium height, with glittering eyes set in immobile features. He looked much like a bronze statue. Without a word he turned and left the chamber.

“Lord king, what do you do?” ventured Tu, still shaking from fright.

“I ride on Fenar’s trail,” answered the king ferociously. “The kingdom is in your hands, Tu. I return when I have crossed swords with this Farsunian or I do not return at all.”

“Nay, nay!” exclaimed Tu. “This is most unwise, King! Heed not what that nameless adventurer said! The emperor of Zarfhaana will never allow you to bring such a force as you named into his realm.”

“Then I will ride over the ruins of Zarfhaana’s cities,” was Kull’s grim reply. “Men avenge their own insults in Atlantis—and though Atlantis has disowned me and I am king of Valusia—still I am a man, by Valka!”

He buckled on his great sword and strode to the door, Tu staring after him.

There before the palace sat four hundred men in their saddles. Three hundred of these were men of the Red Slayers, Kull’s cavalry, and the most terrible soldiery of the earth. They were composed mostly of Valusian hill-men, the strongest and most vigorous of a degenerating race. The remaining hundred were Picts, lean, powerful savages, men of Brule’s tribe, who sat their horses like centaurs and fought like demons when occasion arose.

All these men gave Kull the crown salute as he strode down the palace steps and his eyes lighted with a fierce gleam. He was almost grateful to Fenar for having given him the pretext he needed to quit the monotonous life of the court for awhile and plunge into fierce action—but his thoughts toward the Farsunian were no more kindly for this reason.

At the front of this fierce array sat Brule, chieftain of Valusia’s most formidable allies, and Kelkor, second commander of the Red Slayers.

Kull acknowledged the salute by a brusque gesture and swung into the saddle.

Brule and the commander reined in on either side of him.

“At attention,” came Kelkor’s curt command. “Spurs! Forward!”

The cavalcade moved forward at an easy trot.

The people of Valusia gazed curiously from their windows and doorways, and the throngs on the streets turned as the clatter of silver hoofs resounded through the babble and chatter of trading and commerce. The steeds flung their caparisoned manes; the bronze armor of the warriors glinted in the sun, the pennons on the long lances streamed backward. A moment the small people of the marketplace stopped their gabble as the proud array swept by, blinking in stupid wonder or childish admiration; then the horsemen dwindled down the great white street, the clang of silver on cobblestone died away in the distance, and the people of the city turned back to their commonplace tasks. As the people always do, no matter what kings ride.

Along the broad white streets of Valusia swept the king and his horsemen, out through the suburbs with their spacious estates and lordly palaces; on and on until the golden spires and sapphire towers of Valusia were but a silver shimmer in the distance and the green hills of Zalgara loomed majestically before them.

Night found them encamped high on the slopes of the mountains. The hill people, kin to the Red Slayers, many of them, flocked to the camp with gifts of food and wine, and the warriors, the proud restraint they felt among the cities of the world loosened, talked with them and sang old songs, and exchanged old tales. But Kull walked apart, beyond the glow of the campfires, to gaze out across the mystic vistas of crag and valley. The slopes were softened by verdure and foliage, the vales deepening into shadowy realms of magic, the hills standing out bold and clear in the silver of the moon. The hills of Zalgara had always held a fascination for Kull, They brought to his mind the mountains of Atlantis whose snowy heights he had scaled as a youth, ere he fared forth into the great world to write his name across the stars and make an ancient throne his seat.

Yet there was a difference. The crags of Atlantis rose stark and gaunt; her cliffs were barren and rugged. The mountains of Atlantis were brutal and terrible with youth, even as Kull. Age had not softened thier might. The hills of Zalgara rose up like ancient gods, but green groves and waving verdure laughed upon their shoulders and cliffs, and their outline was soft and flowing. Age—age—thought Kull; many a drifting century had worn away their craggy splendor; they were mellow and beautiful with antiquity. Ancient mountains dreaming of bygone kings whose careless feet had trod their sward.

Like a red wave the thought of Fenar’s insult swept away these broodings. Hands clenched in fury, Kull flung back his shoulders to gaze full into the calm eye of the moon.

“Helfara and Hotath doom my soul to everlasting Hell if I wreak not my vengeance on Fenar!” he snarled.

The night breeze whispered among the trees as if in answer to the heathen vow.

Ere scarlet dawn had burst like a red rose over the hills of Zalgara Kull’s cavalcade was in the saddle. The first glints of morning shone on the lance points, the helmets and the shields as the band wound its way through green-waving vales and up over long undulating slopes.

“We ride into the sunrise,” remarked Kelkor.

“Aye,” was Brule’s grim response. “And some of us ride beyond the sunrise.”

Kelkor shrugged his shoulders. “So be it. That is the destiny of a warrior.”

Kull glanced at the commander. Straight as a spear sat Kelkor in his saddle, inflexible, unbending as a statue of steel. The commander had always reminded the king of a fine sword of polished steel. A man of terrific power and mighty forces, the most powerful thing about him was his absolute control of himself. An icy calmness had always characterized his words and deeds. In the heat and vituperation of council, in the wild wrack of battle, Kelkor was always cool, never confused. He had few friends, nor did he strive to make friends. His qualities alone had raised him from an unknown warrior in the ranks of the mercenaries to the second highest rank in Valusian armies—and only the fact of his birth debarred him from the highest. For custom decreed that the lord commander of troops must be a Valusian and Kelkor was a Lemurian. Yet he looked more a Valusian than a Lemurian as he sat his horse, for he was built differently from most of his race, being tall and leanly but strongly built. His strange eyes alone betrayed his race.

Another dawn found them riding down from the foothills that debauched out into the Camoonian desert, a vast wasteland, uninhabited, a dreary waste of yellow sands. No trees grew there, nor even bushes, nor were there any streams of water. All day they rode, stopping only a short time at midday to eat and rest the horses, though the heat was almost intolerable. The men, inured as they were, wilted beneath the heat. Silence reigned save for the clank of stirrups and armor, the creak of sweating saddles, and the monotonous scruff of hoof through the deep sands. Even Brule hung his corselet on his saddlebow. But Kelkor sat upright and unmoved, under the weight of full armor, seemingly untouched by the heat and discomfort that harried the rest.

“Steel, all steel,” thought Kull in admiration, secretly wondering if he could ever attain the perfect mastery over himself that this man, also a barbarian, had attained.

Two days’ journey brought them out of the desert and into the low hills that marked the confines of Zarfhaana. At the borderline they were stopped by two Zarfhaanian riders.

“I am Kull of Valusia,” the king answered abruptly. “I ride on the trail of Fenar. Seek not to hinder my passing. I will be responsible to your emperor.”

The two horsemen reined aside to let the cavalcade pass and as the clashing hoofs faded in the distance, one spoke to the other.

“I win our wager. The king of Valusia rides himself.”

“Aye,” the other replied. “These barbarians avenge their own wrongs. Had the king been a Valusian, by Valka, you had lost.”

The vales of Zarfhaana echoed to the tramp of Kull’s riders. The peaceful country people flocked out of their villages to watch the fierce warriors sweep by, and word went to the north and the south, the west and the east, that Kull of Valusia rode eastward.

Just beyond the frontier, Kull, having sent an envoy to the Zarfhaanian emperor to assure him of their peaceful intention, held council with Brule, Ka-yanna, and Kelkor.

“They have the start of us by many days,” said Kull, “and we must lose no time in searching for their trail. These country people will lie to us; we must scent out our own trail, as wolves scent out the spoor of a deer.”

“Let me question these fellows,” said Ka-yanna, with a vicious curl of his thick, sensual lips. I will guarantee to make them speak truthfully.”

Kull glanced at him inquiringly.

“There are ways,” purred the Valusian.

“Torture?” grunted Kull, his lip writhing in unveiled contempt. “Zarfhaana is a friendly nation.”

“What cares the emperor for a few wretched villagers?” blandly asked Ka-yanna.

“Enough.” Kull swept aside the suggestion with true Atlantean abhorrence, but Brule raised his hand for attention.

“Kull,” said he, “I like this fellow’s plan no more than you, but at times even a swine speaks truth.” Ka-yanna’s lips writhed in rage, but the Pict gave him no heed. “Let me take a few of my men among the villagers and question them. I will only frighten a few, harming no one; otherwise we may spend weeks in futile search.”

“There spake the barbarian,” said Kull with the friendly maliciousness that existed between the two.

“In what city of the Seven Empires were you born, lord king?” asked the Pict with sarcastic deference.

Kelkor dismissed this byplay with an impatient wave of his hand.

“Here is our position,” said he, scrawling a map in the ashes of the campfire with his scabbard end. “North Fenar is not likely to go—assuming as we do that he does not intend remaining in Zarfhaana—because beyond Zarfhaana is the sea, swarming with pirates and sea-rovers. South he will not go because there lies Thurania, foe of his nation. Now it is my guess that he will strike straight east as he was travelling, cross Zarfhaana’s eastern border somewhere near the frontier city of Talunia, and go into the wastelands of Grondar; thence I believe he will turn south seeking to gain Farsun—which lies west of Valusia—through the small principalities south of Thurania.”

“Here is much supposition, Kelkor,” said Kull. “If Fenar wishes to win through to Farsun, why in Valka’s name did he strike in the exactly opposite direction?”

“Because, as you know, Kull, in these unsettled times all our borders, except the easternmost, are closely guarded. He could never have gotten through without proper explanation, much less have carried the countess with him.”

“I believe Kelkor is right, Kull,” said Brule, eyes dancing with impatience to be in the saddle. “His arguments sound logical, at any rate.”

“As good a plan as any,” replied Kull. “We ride east.”

And east they rode through the long lazy days, entertained and feasted at every halt by the kindly Zarfhaanian people. A soft and lazy land, thought Kull, a dainty girl waiting helplessly for some ruthless conqueror—Kull dreamed his dreams as his riders’ hoofs beat out their tattoo through the dreamy valleys and the verdant woodlands. Yet he drove his men hard, giving them no rest, for ever behind his far-sweeping and imperial visions of blood-stained glory and wild conquest, there loomed the phantom of his hate, the relentless hatred of the savage, before which all other desires must give way.

They swung wide of cities and large towns for Kull wished not to give his fierce warriors opportunity to become embroiled in some dispute with the inhabitants. The cavalcade was nearing the border city of Talunia, Zarfhaana’s last eastern outpost, when the envoy sent to the emperor in his city to the north rejoined them with the word that the emperor was quite willing that Kull should ride through his land, and requested the Valusian king to visit him on his return. Kull smiled grimly at the irony of the situation, considering the fact that even while the emperor was giving benevolent permission, Kull was already far into his country with his men.

Kull’s warriors rode into Talunia at dawn, after an all night’s ride, for he had thought that perhaps Fenar and the countess, feeling temporarily safe, would tarry awhile in the border city and he wished to precede the word of his coming.

Kull encamped his men some distance outside the city walls and entered the city alone save for Brule. The gates were readily opened to him when he had shown the regal signet of Valusia and the symbol sent him by the Zarfhaanian emperor.

“Hark ye,” said Kull to the commander of the gate guards, “are Fenar and Lala-ah in this city?”

“That I cannot say,” the soldier answered. “They entered at this gate many days since, but whether they are still in the city or not, I do not know.”

“Listen, then,” said Kull, slipping a gemmed bracelet from his mighty arm, “I am merely a wandering Valusian noble, accompanied by a Pictish companion. None need know who I am, understand?”

The soldier eyed the costly ornament covetously. “Very good, lord king, but what of your soldiers encamped in the forest?”

“They are concealed from the eyes of the city. If any peasant enters your gate, question him and if he tells you of a force encamped, hold him prisoner for some trumped-up reason, until this time tomorrow. For by then I shall have secured the information I desire.”

“Valka’s name, lord king, you would make me a traitor of sorts!” expostulated the soldier. “I think not that you plan treachery, yet—”

Kull changed his tactics. “Have you not orders to obey your emperor’s command? Have I not shown you his symbol of command? Dare you disobey? Valka, it is you who would be the traitor!”

After all, reflected the soldier, this was the truth—he would not be bribed, no! no! But since it was the order of a king who bore authority from his emperor—

Kull handed over the bracelet with no more than a faint smile betraying his contempt of mankind’s way of lulling their consciences into the path of their desires, refusing to admit that they violated their own moral senses, even to themselves.

The king and Brule walked through the streets, where the tradespeople were just beginning to stir. Kull’s giant stature and Brule’s bronze skin drew many curious stares, but no more than would be expected to be accorded strangers. Kull began to wish he had brought Kelkor or a Valusian, for Brule could not possibly disguise his race, and since Picts were seldom seen in these eastern cities, it might cause comment that would reach the hearing of those they sought.

They sought a modest tavern where they secured a room, then took their seats in the drinking room, to see if they might hear aught of what they wished to hear. But the day wore on and nothing was said of the fugitive couple, nor did carefully veiled questions elicit any knowledge. If Fenar and Lala-ah were still in Talunia they were certainly not advertising their presence. Kull would have thought that the presence of a dashing gallant and a beautiful young girl of royal blood in the city would have been the subject of at least some comment, but such seemed not to be the case.

Kull intended to fare forth that night upon the streets, even to the extent of committing some marauding if necessary, and failing in this to reveal his identity to the lord of the city the next morning, demanding that the culprits be handed over to him. Yet Kull’s ferocious pride rebelled at such an act. This seemed the most logical course, and was one which Kull would have followed had the matter been merely a diplomatic or political one. But Kull’s fierce pride was roused and he was loath to ask aid from anyone in the consummating of his vengeance.

Night was falling as the comrades stepped into the streets, still thronged with voluble people and lighted by torches set along the streets. They were passing a shadowy side-street when a cautious voice halted them. From the dimness between the great building a claw-like hand beckoned. With a swift glance at each other, they stepped forward, warily loosening their daggers in their sheaths as they did so. An aged crone, ragged, stooped with age, stole from the shadows.

“Aye, King Kull, what seek ye in Talunia?” her voice was a shrill whisper.

Kull’s fingers closed about his dagger hilt more firmly as he replied guardedly.

“How know you my name?”

“The marketplaces speak and hear,” she answered with a low cackle of unhallowed mirth. “A man saw and recognized you today in the tavern and the word has gone from mouth to mouth.”

Kull cursed softly.

“Hark ye!” hissed the woman. “I can lead ye to those ye seek—if ye be willing to pay the price.”

“I will fill your apron with gold,” Kull answered swiftly.

“Good. Listen now. Fenar and the countess are apprized of your arrival. Even now they are preparing their escape. They have hidden in a certain house since early evening when they learned that you had come, and soon they leave their hiding place—”

“How can they leave the city?” interrupted Kull. “The gates are shut at sunset.”

“Horses await them at a postern gate in the eastern wall. The guard has been bribed. Fenar has many friends in Talunia.”

“Where hide they now?”

The crone stretched forth a shrivelled hand. “A token of good faith, lord king,” she wheedled.

Kull put a coin in her hand and she smirked and made a grotesque curtsey.

“Follow me, lord king,” and she hobbled away swiftly into the shadows.

The king and his companion followed her uncertainly through narrow, winding streets until she halted before an unlit huge building in a squalid part of the city.

“They hide in a room at the head of the stairs leading from the lower chamber opening into the street, lord king.”

“How do you know that they do?” asked Kull suspiciously. “Why should they pick such a wretched place in which to hide?”

The woman laughed silently, rocking to and fro in her uncanny mirth.

“As soon as I made sure you were in Talunia, lord king, I hurried to the mansion where they had their abode and told them, offering to lead them to a place of concealment! Ho, ho, ho! They paid me good gold coins!”

Kull stared at her silently.

“Now, by Valka,” said he, “I knew not civilization could produce a thing like this woman. Here, female, guide Brule to the gate where await the horses. Brule, go with her there and await my coming—perchance Fenar might give me the slip here—“

“But Kull,” protested Brule, “you go not into yon dark house alone—bethink you this might all be an ambush!”

“This woman dare not betray me!” and the crone shuddered at the grim response. “Haste ye!”

As the two forms melted into the darkness, Kull entered the house. Groping with his hands until his feline-gifted eyes became accustomed to the total darkness, he found the stair and ascended it, dagger in hand, walking stealthily and on the lookout for creaking steps. For all his size, the king moved as easily and silently as a leopard, and had the watcher at the head of the stairs been awake, it is doubtful if he would have heard his coming.

As it was, he awakened when Kull’s hand was clapped over his mouth, only to fall back temporarily unconscious as Kull’s fist found his jaw.

The king crouched a moment above his victim, straining his faculties for any sound that might betoken that he had been heard. Utter silence reigned. He stole to the door. Ah, his keen senses detected a low confused mumble as of people whispering—a guarded movement—with one leap Kull hurled the door open and hurled himself into the room. He halted not to weigh chances; there might have been a roomful of assassins waiting for him for all he thought of the thing.

Everything then happened in an instant. Kull saw a barren room, lighted by moonlight that streamed in at the window, he caught a glimpse of two forms clambering through this window, one apparently carrying the other, a fleeting glance of a pair of dark, daring eyes in a face of piquant beauty, another laughing, reckless handsome face—all this he saw confusedly as he cleared the whole room with a tigerish bound, a roar of pure bestial ferocity breaking from his lips at the sight of his foe escaping. The window was empty even as he hurled across the sill, and raging and furious, he caught another glimpse, two forms darting into the shadows of a nearby maze of buildings—a silvery mocking laugh floated back to him, another stronger, more mocking. Kull flung a leg over the sill and dropped the sheer thirty feet to the earth, disdaining the rope ladder that still swung from the window. He could not hope to follow them through that maze of streets, which they doubtless knew much better than he.

Sure of their destination, however, he raced toward the gate in the eastern wall, which from the crone’s description was not far distant. However, some time elapsed before he arrived and when he did it was only to find Brule and the hag there.

“Nay,” said Brule. “The horses are here, but none has come for them.”

Kull cursed savagely. Fenar had tricked him after all, and the woman also. Suspecting treachery, the horses at that gate had only served as a blind. Fenar was doubtless escaping through some other gate, then.

“Swift!” shouted Kull. “Haste to the camp and have the men mount! I follow Fenar’s trail.” And leaping upon one of the horses he was gone.

Brule mounted the other and rode toward the camp.

The crone watched them go, shaking with unholy mirth. After awhile she heard the drum of many hoofs passing the city.

“Ho, ho, ho! They ride into the sunrise—and who rides back from beyond the sunrise?”

All night Kull rode, striving to cut down the lead the Farsunian and the girl had gained. He knew they dared not remain in Zarfhaana and as the sea lay to the north, and Thurania, Farsun’s ancient enemy, to the south, then there lay but one course for them—the road to Grondar.

The stars were paling when the ramparts of the eastern hills rose starkly against the sky in front of the king, and dawn was stealing over the grasslands as Kull’s weary steed toiled up the pass and halted a moment at the summit. Here the fugitives must have passed for these cliffs stretched the whole length of the Zarfhaanian border and the next nearest pass was many a mile to the north. The Zarfhaanian in the small tower that reared up in the pass, hailed the king, but Kull replied with a gesture and rode on.

At the crest of the pass he halted. There beyond lay Grondar. The cliffs rose as abruptly on the eastern side as they did upon the west and from their feet the grasslands stretched away endlessly. Mile upon countless mile of tall waving savannah land met his eyes, seemingly inhabited only by the herds of buffalo and deer that roamed those wild expanses. The east was fast reddening and as Kull sat his horse the sun flamed up over the savannahs like a wild blaze of fire, making it appear to the king as if all the grasslands were ablaze—limning the motionless horseman against its flame, so that man and horse seemed a single dark statue against the red morning to the riders who were just entering the first defile of the pass far behind. Then he vanished from their gaze as he spurred forward.

“He rides into the sunrise,” muttered the warriors. “Who rides back from the sunrise?”

The sun was high in the sky when the troop overtook Kull, the king having stopped to consult with his companions.

“Have your Picts spread out,” said Kull. “Fenar and the countess will try to turn south any time now, for no man cares to ride any further into Grondar than need be. They might even seek to get past us and win back into Zarfhaana.”

So they rode in open formation, Brule’s Picts ranging like lean wolves far afield to the north and the south.

But the fugitives’ trail led straight onward, Kull’s trained eyes easily following the course through the tall grass, marking where the grass had been trampled and beaten down by the horses’ hoofs. Evidently the countess and her lover rode alone.

And on into the wild country of Grondar they rode, pursuers and pursued.

How Fenar managed to keep that lead, Kull could not understand, but the soldiers were forced to spare their horses, while Fenar had extra steeds and could change from one to another, thus keeping each comparatively fresh.

Kull had sent no envoy to the king of Grondar. The Grondarians were a wild, half-civilized race, of whom little was known by the rest of the world, save that their raiding parties sometimes swept out of the grasslands to sweep the borders of Thurania and the lesser nations with torch and sword. Westward, their borders were plainly marked, clearly defined and carefully guarded, that is by their neighbors, but how far easterly their kingdom extended no one knew. It was vaguely supposed that their country extended to, and possibly included, that vast expanse of untenable wilderness spoken of in myth and legend as The World’s End.

Several days of hard riding had passed with neither sight of the fugitives nor any other human, when a Pictish rider sighted a band of horsemen approaching from the south.

Kull halted his force and waited. They rode up and halted at a distance, a band of some four hundred Grondarian warriors, fierce, leanly-built men, clad in leather garments and rude armor.

Their leader rode forth. “Stranger, what do ye in this land?”

Kull answered, “We pursue a disobedient subject and her lover, and we ride in peace. We have no dispute with Grondar.”

The Grondarian sneered. “Men who ride in Grondar carry their lives in their right hands, stranger.”

“Then, by Valka,” roared Kull, losing patience, “my right hand is stronger to defend than all Grondar is to assail! Stand aside ere we trample you!”

“Lances at rest!” came Kelkor’s curt voice; the forest of spears lowered as one, the warriors leaning forward.

The Grondarians gave back before that formidable array, unable, as they knew, to stand in the open the charge of fully armed horsemen. They reined aside, sitting their horses sullenly as the Valusians swept by them. The leader shouted after them. “Ride on, fools! Who ride beyond the sunrise—return not!”

They rode, and though bands of horsemen circled their tracks at a distance like hawks, and they kept a heavy guard at night, the riders came not nearer nor were the outriders molested in any way.

The grasslands continued with never a hill or forest to break their monotony. Sometimes they came upon the almost obliterated ruins of some ancient city, mute reminders of the bloody days when, ages and ages since, the ancestors of the Grondarians had appeared from nowhere in particular and had conquered the original inhabitants of the land. They sighted no inhabited cities, none of the rough habitations of the Grondarians, for their way led through an especially wild, unfrequented part of the land. It became evident that Fenar intended not to turn back; his trail led straight east and whether he hoped to find sanctuary somewhere in that nameless land or whether he was seeking merely to tire his pursuers out, could not be said.

Long days of riding and then they came to a great river meandering through the plain. At its banks the grasslands came to an abrupt halt, and beyond, on the further side, a barren desert stretched to the horizon.

An ancient man stood upon the bank and a large, flat boat floated on the sullen surface of the water. The man was aged, but mightily built, as huge as Kull himself. He was clad only in ragged garments, seemingly as ancient as himself, but there was something kingly and awe-inspiring about the man. His snowy hair fell to his shoulders and his huge white beard, wild and unkempt, came almost to his waist. From beneath white, lowering brows, great luminous eyes blazed, undimmed by age.

“Stranger, who have the bearing of a king,” said he to Kull in a great deep resonant voice, “would ye cross the river?”

“Aye,” said Kull, “if they we seek crossed.”

“A man and a girl rode my ferry yesterday at dawn,” was the answer.

“Name of Valka!” swore Kull. “I could find it in me to admire the fool’s courage! What city lies beyond this river, ferryman?”

“No city lies beyond,” said the Elder man. “This river marks the border of Grondar—and the world!”

“How!” ejaculated Kull. “Have we ridden so far? I had thought that the desert which is the end of the world was part of Grondar’s realm.”

“Nay. Grondar ends here. Here is the end of the world; beyond is magic and the unknown. Here is the boundary of the world; there begins the realm of horror and mysticism. This is the river Stagus and I am Karon the Ferryman.”

Kull looked at him in wonder, little knowing that he gazed upon one who should go down the dim centuries until myth and legend had changed the truth and Karon the Ferryman had become the boat-man of Hades.

“You are very aged,” said Kull curiously, while the Valusians looked on the man with wonder and the savage Picts in superstitious awe.

“Aye. I am a man of the Elder Race, who ruled the world before Valusia was, or Grondar or Zarfhaana, riders from the sunset. Ye would cross this river? Many a warrior, many a king, have I ferried across. Remember, they who ride beyond the sunrise, return not! For of all the thousands who have crossed the Stagus, not one has returned. Three hundred years have passed since first I saw the light, king of Valusia. I ferried the army of King Gaar the Conqueror when he rode into World’s End with all his mighty hosts. Seven days they were passing over, yet no man of them came back. Aye, the sound of battle and the clash of swords clanged out over the wastelands for a long while from sun to sun, but when the moon shone all was silence. Mark this, Kull, no man has ever returned from beyond the Stagus. Nameless horrors lurk in yonder lands and terrible are the ghastly shapes of doom I glimpse beyond the river in the vagueness of dusk and the grey of early dawn. Mark ye, Kull.”

Kull turned in his saddle and eyed his men.

“Here my commands cease,” said he. “As for myself, I ride on Fenar’s trail if it lead to Hell and beyond. Yet I bid no man follow beyond this river. Ye all have my permission to return to Valusia, nor shall any word of blame ever be spoken of you.”

Brule reined to Kull’s side. “I ride with the king,” he said curtly, and his Picts raised an acquiescing shout.

Kelkor rode forward. “They who would return, take a single pace forward,” said he.

The metal ranks sat motionless as statues.

“They ride, Kull,” grinned Brule.

A fierce pride rose in the king’s savage soul. He spoke a single sentence, a sentence which thrilled his warriors more than an accolade.

“Ye are men.”

Karon ferried them across, rowing over and returning until the entire force stood on the eastern bank. And though the boat was heavy and the ancient man rowed alone, yet his clumsy oars drove the unwieldy craft swiftly through the water and at the last journey he was no more weary than at the start.

Kull spake. “Since the desert throngs with wild things, how is it that none come into the lands of men?”

Karon pointed to the river, and looking closely Kull saw that the river swarmed with serpents and small freshwater sharks.

“No man swims this river,” said the ferryman. “Neither man nor mammoth.”

“Forward,” said Kull. “Forward; we ride. The land is free before us.”