Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

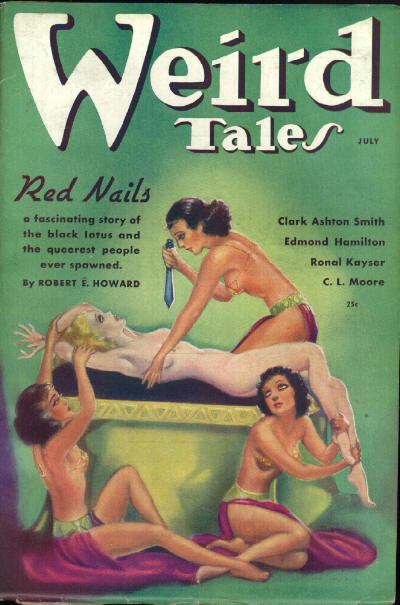

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 28, Nos. 1-3 (July, August/September, and October 1936);

I have moved the illustrations around a little so they are placed more sensibly in regards to what they depict.

Note that the draft is divided into un-numbered chapters. It also has quite a few misspellings

and even missing words, but I have not bothered to mark any of that stuff.

| 1. The Skull on the Crag 2. By the Blaze of the Fire Jewels 3. The People of the Feud 4. Scent of Black Lotus |

5. Twenty Red Nails 6. The Eyes of Tascela 7. He Comes from the Dark Draft |

The woman on the horse reined in her weary steed. It stood with its legs wide-braced, its head drooping, as if it found even the weight of the gold-tassled, red-leather bridle too heavy. The woman drew a booted foot out of the silver stirrup and swung down from the gilt-worked saddle. She made the reins fast to the fork of a sapling, and turned about, hands on her hips, to survey her surroundings.

Nearly four years ago, WEIRD TALES published a story called “The Phoenix on the Sword,” built around a barbarian adventurer named Conan, who had become king of a country by sheer force of valor and brute strength. The author of that story was Robert E. Howard, who was already a favorite with the readers of this magazine for his stories of Solomon Kane, the dour English Puritan and redresser of wrongs. The stories about Conan were speedily acclaimed by our readers, and the barbarian’s weird adventures became immensely popular. The story presented herewith is one of the most powerful and eery weird tales yet written about Conan. We commend this story to you, for we know you will enjoy it through and through.

They were not inviting. Giant trees hemmed in the small pool where her horse had just drunk. Clumps of undergrowth limited the vision that quested under the somber twilight of the lofty arches formed by intertwining branches. The woman shivered with a twitch of her magnificent shoulders, and then cursed.

She was tall, full-bosomed and large-limbed, with compact shoulders. Her whole figure reflected an unusual strength, without detracting from the femininity of her appearance. She was all woman, in spite of her bearing and her garments. The latter were incongruous, in view of her present environs. Instead of a skirt she wore short, wide-legged silk breeches, which ceased a hand’s breadth short of her knees, and were upheld by a wide silken sash worn as a girdle. Flaring-topped boots of soft leather came almost to her knees, and a low-necked, wide-collared, wide-sleeved silk shirt completed her costume. On one shapely hip she wore a straight double-edged sword, and on the other a long dirk. Her unruly golden hair, cut square at her shoulders, was confined by a band of crimson satin.

Against the background of somber, primitive forest she posed with an unconscious picturesqueness, bizarre and out of place. She should have been posed against a background of sea-clouds, painted masts and wheeling gulls. There was the color of the sea in her wide eyes. And that was as it should have been, because this was Valeria of the Red Brotherhood, whose deeds are celebrated in song and ballad wherever seafarers gather.

She strove to pierce the sullen green roof of the arched branches and see the sky which presumably lay about it, but presently gave it up with a muttered oath.

Leaving her horse tied she strode off toward the east, glancing back toward the pool from time to time in order to fix her route in her mind. The silence of the forest depressed her. No birds sang in the lofty boughs, nor did any rustling in the bushes indicate the presence of any small animals. For leagues she had traveled in a realm of brooding stillness, broken only by the sounds of her own flight.

She had slaked her thirst at the pool, but she felt the gnawings of hunger and began looking about for some of the fruit on which she had sustained herself since exhausting the food she had brought in her saddle-bags.

Ahead of her, presently, she saw an outcropping of dark, flint-like rock that sloped upward into what looked like a rugged crag rising among the trees. Its summit was lost to view amidst a cloud of encircling leaves. Perhaps its peak rose above the tree-tops, and from it she could see what lay beyond—if, indeed, anything lay beyond but more of this apparently illimitable forest through which she had ridden for so many days.

A narrow ridge formed a natural ramp that led up the steep face of the crag. After she had ascended some fifty feet she came to the belt of leaves that surrounded the rock. The trunks of the trees did not crowd close to the crag, but the ends of their lower branches extended about it, veiling it with their foliage. She groped on in leafy obscurity, not able to see either above or below her; but presently she glimpsed blue sky, and a moment later came out in the clear, hot sunlight and saw the forest roof stretching away under her feet.

She was standing on a broad shelf which was about even with the tree-tops, and from it rose a spire-like jut that was the ultimate peak of the crag she had climbed. But something else caught her attention at the moment. Her foot had struck something in the litter of blown dead leaves which carpeted the shelf. She kicked them aside and looked down on the skeleton of a man. She ran an experienced eye over the bleached frame, but saw no broken bones nor any sign of violence. The man must have died a natural death; though why he should have climbed a tall crag to die she could not imagine.

She scrambled up to the summit of the spire and looked toward the horizons. The forest roof—which looked like a floor from her vantage-point—was just as impenetrable as from below. She could not even see the pool by which she had left her horse. She glanced northward, in the direction from which she had come. She saw only the rolling green ocean stretching away and away, with only a vague blue line in the distance to hint of the hill-range she had crossed days before, to plunge into this leafy waste.

West and east the view was the same; though the blue hill-line was lacking in those directions. But when she turned her eyes southward she stiffened and caught her breath. A mile away in that direction the forest thinned out and ceased abruptly, giving way to a cactus-dotted plain. And in the midst of that plain rose the walls and towers of a city. Valeria swore in amazement. This passed belief. She would not have been surprized to sight human habitations of another sort—the beehive-shaped huts of the black people, or the cliff-dwellings of the mysterious brown race which legends declared inhabited some country of this unexplored region. But it was a startling experience to come upon a walled city here so many long weeks’ march from the nearest outposts of any sort of civilization.

Her hands tiring from clinging to the spire-like pinnacle, she let herself down on the shelf, frowning in indecision. She had come far—from the camp of the mercenaries by the border town of Sukhmet amidst the level grasslands, where desperate adventurers of many races guard the Stygian frontier against the raids that come up like a red wave from Darfar. Her flight had been blind, into a country of which she was wholly ignorant. And now she wavered between an urge to ride directly to that city in the plain, and the instinct of caution which prompted her to skirt it widely and continue her solitary flight.

Her thoughts were scattered by the rustling of the leaves below her. She wheeled cat-like, snatched at her sword; and then she froze motionless, staring wide-eyed at the man before her.

He was almost a giant in stature, muscles rippling smoothly under his skin which the sun had burned brown. His garb was similar to hers, except that he wore a broad leather belt instead of a girdle. Broadsword and poniard hung from this belt.

“Conan, the Cimmerian!” ejaculated the woman. “What are you doing on my trail?”

He grinned hardly, and his fierce blue eyes burned with a light any woman could understand as they ran over her magnificent figure, lingering on the swell of her splendid breasts beneath the light shirt, and the clear white flesh displayed between breeches and boot-tops.

“Don’t you know?” he laughed. “Haven’t I made my admiration for you plain ever since I first saw you?”

“A stallion could have made it no plainer,” she answered disdainfully. “But I never expected to encounter you so far from the ale-barrels and meat-pots of Sukhmet. Did you really follow me from Zarallo’s camp, or were you whipped forth for a rogue?”

He laughed at her insolence and flexed his mighty biceps.

“You know Zarallo didn’t have enough knaves to whip me out of camp,” he grinned. “Of course I followed you. Lucky thing for you, too, wench! When you knifed that Stygian officer, you forfeited Zarallo’s favor and protection, and you outlawed yourself with the Stygians.”

“I know it,” she replied sullenly. “But what else could I do? You know what my provocation was.”

“Sure,” he agreed. “If I’d been there, I’d have knifed him myself. But if a woman must live in the war-camps of men, she can expect such things.”

Valeria stamped her booted foot and swore.

“Why won’t men let me live a man’s life?”

“That’s obvious!” Again his eager eyes devoured her. “But you were wise to run away. The Stygians would have had you skinned. That officer’s brother followed you; faster than you thought, I don’t doubt. He wasn’t far behind you when I caught up with him. His horse was better than yours. He’d have caught you and cut your throat within a few more miles.”

“Well?” she demanded.

“Well what?” He seemed puzzled.

“What of the Stygian?”

“Why, what do you suppose?” he returned impatiently. “I killed him, of course, and left his carcass for the vultures. That delayed me, though, and I almost lost your trail when you crossed the rocky spurs of the hills. Otherwise I’d have caught up with you long ago.”

“And now you think you’ll drag me back to Zarallo’s camp?” she sneered.

“Don’t talk like a fool,” he grunted. “Come, girl, don’t be such a spitfire. I’m not like that Stygian you knifed, and you know it.”

“A penniless vagabond,” she taunted.

He laughed at her.

“What do you call yourself? You haven’t enough money to buy a new seat for your breeches. Your disdain doesn’t deceive me. You know I’ve commanded bigger ships and more men than you ever did in your life. As for being penniless—what rover isn’t, most of the time? I’ve squandered enough gold in the sea-ports of the world to fill a galleon. You know that, too.”

“Where are the fine ships and the bold lads you commanded, now?” she sneered.

“At the bottom of the sea, mostly,” he replied cheerfully. “The Zingarans sank my last ship off the Shemite shore—that’s why I joined Zarallo’s Free Companions. But I saw I’d been stung when we marched to the Darfar border. The pay was poor and the wine was sour, and I don’t like black women. And that’s the only kind that came to our camp at Sukhmet—rings in their noses and their teeth filed—bah! Why did you join Zarallo? Sukhmet’s a long way from salt water.”

“Red Ortho wanted to make me his mistress,” she answered sullenly. “I jumped overboard one night and swam ashore when we were anchored off the Kushite coast. Off Zabhela, it was. There a Shemite trader told me that Zarallo had brought his Free Companies south to guard the Darfar border. No better employment offered. I joined an east-bound caravan and eventually came to Sukhmet.”

“It was madness to plunge southward as you did,” commented Conan, “but it was wise, too, for Zarallo’s patrols never thought to look for you in this direction. Only the brother of the man you killed happened to strike your trail.”

“And now what do you intend doing?” she demanded.

“Turn west,” he answered. “I’ve been this far south, but not this far east. Many days’ traveling to the west will bring us to the open savannas, where the black tribes graze their cattle. I have friends among them. We’ll get to the coast and find a ship. I’m sick of the jungle.”

“Then be on your way,” she advised. “I have other plans.”

“Don’t be a fool!” He showed irritation for the first time. “You can’t keep on wandering through this forest.”

“I can if I choose.”

“But what do you intend doing?”

“That’s none of your affair,” she snapped.

“Yes, it is,” he answered calmly. “Do you think I’ve followed you this far, to turn around and ride off empty-handed? Be sensible, wench. I’m not going to harm you.”

He stepped toward her, and she sprang back, whipping out her sword.

“Keep back, you barbarian dog! I’ll spit you like a roast pig!”

He halted, reluctantly, and demanded: “Do you want me to take that toy away from you and spank you with it?”

“Words! Nothing but words!” she mocked, lights like the gleam of the sun on blue water dancing in her reckless eyes.

He knew it was the truth. No living man could disarm Valeria of the Brotherhood with his bare hands. He scowled, his sensations a tangle of conflicting emotions. He was angry, yet he was amused and filled with admiration for her spirit. He burned with eagerness to seize that splendid figure and crush it in his iron arms, yet he greatly desired not to hurt the girl. He was torn between a desire to shake her soundly, and a desire to caress her. He knew if he came any nearer her sword would be sheathed in his heart. He had seen Valeria kill too many men in border forays and tavern brawls to have any illusions about her. He knew she was as quick and ferocious as a tigress. He could draw his broadsword and disarm her, beat the blade out of her hand, but the thought of drawing a sword on a woman, even without intent of injury, was extremely repugnant to him.

“Blast your soul, you hussy!” he exclaimed in exasperation. “I’m going to take off your——”

He started toward her, his angry passion making him reckless, and she poised herself for a deadly thrust. Then came a startling interruption to a scene at once ludicrous and perilous.

“What’s that?”

It was Valeria who exclaimed, but they both started violently, and Conan wheeled like a cat, his great sword flashing into his hand. Back in the forest had burst forth an appalling medley of screams—the screams of horses in terror and agony. Mingled with their screams there came the snap of splintering bones.

“Lions are slaying the horses!” cried Valeria.

“Lions, nothing!” snorted Conan, his eyes blazing. “Did you hear a lion roar? Neither did I! Listen at those bones snap—not even a lion could make that much noise killing a horse.”

He hurried down the natural ramp and she followed, their personal feud forgotten in the adventurers’ instinct to unite against common peril. The screams had ceased when they worked their way downward through the green veil of leaves that brushed the rock.

“I found your horse tied by the pool back there,” he muttered, treading so noiselessly that she no longer wondered how he had surprized her on the crag. “I tied mine beside it and followed the tracks of your boots. Watch, now!”

They had emerged from the belt of leaves, and stared down into the lower reaches of the forest. Above them the green roof spread its dusky canopy. Below them the sunlight filtered in just enough to make a jade-tinted twilight. The giant trunks of trees less than a hundred yards away looked dim and ghostly.

“The horses should be beyond that thicket, over there,” whispered Conan, and his voice might have been a breeze moving through the branches. “Listen!”

Valeria had already heard, and a chill crept through her veins; so she unconsciously laid her white hand on her companion’s muscular brown arm. From beyond the thicket came the noisy crunching of bones and the loud rending of flesh, together with the grinding, slobbering sounds of a horrible feast.

“Lions wouldn’t make that noise,” whispered Conan. “Something’s eating our horses, but it’s not a lion—Crom!”

The noise stopped suddenly, and Conan swore softly. A suddenly risen breeze was blowing from them directly toward the spot where the unseen slayer was hidden.

“Here it comes!” muttered Conan, half lifting his sword.

The thicket was violently agitated, and Valeria clutched Conan’s arm hard. Ignorant of jungle-lore, she yet knew that no animal she had ever seen could have shaken the tall brush like that.

“It must be as big as an elephant,” muttered Conan, echoing her thought. “What the devil——” His voice trailed away in stunned silence.

Through the thicket was thrust a head of nightmare and lunacy. Grinning jaws bared rows of dripping yellow tusks; above the yawning mouth wrinkled a saurian-like snout. Huge eyes, like those of a python a thousand times magnified, stared unwinkingly at the petrified humans clinging to the rock above it. Blood smeared the scaly, flabby lips and dripped from the huge mouth.

The head, bigger than that of a crocodile, was further extended on a long scaled neck on which stood up rows of serrated spikes, and after it, crushing down the briars and saplings, waddled the body of a titan, a gigantic, barrel-bellied torso on absurdly short legs. The whitish belly almost raked the ground, while the serrated back-bone rose higher than Conan could have reached on tiptoe. A long spiked tail, like that of a gargantuan scorpion, trailed out behind.

“Back up the crag, quick!” snapped Conan, thrusting the girl behind him. “I don’t think he can climb, but he can stand on his hind-legs and reach us——”

With a snapping and rending of bushes and saplings the monster came hurtling through the thickets, and they fled up the rock before him like leaves blown before a wind. As Valeria plunged into the leafy screen a backward glance showed her the titan rearing up fearsomely on his massive hinder legs, even as Conan had predicted. The sight sent panic racing through her. As he reared, the beast seemed more gigantic than ever; his snouted head towered among the trees. Then Conan’s iron hand closed on her wrist and she was jerked headlong into the blinding welter of the leaves, and out again into the hot sunshine above, just as the monster fell forward with his front feet on the crag with an impact that made the rock vibrate.

Behind the fugitives the huge head crashed through the twigs, and they looked down for a horrifying instant at the nightmare visage framed among the green leaves, eyes flaming, jaws gaping. Then the giant tusks clashed together futilely, and after that the head was withdrawn, vanishing from their sight as if it had sunk in a pool.

Peering down through broken branches that scraped the rock, they saw it squatting on its haunches at the foot of the crag, staring unblinkingly up at them.

Valeria shuddered.

“How long do you suppose he’ll crouch there?”

Conan kicked the skull on the leaf-strewn shelf.

“That fellow must have climbed up here to escape him, or one like him. He must have died of starvation. There are no bones broken. That thing must be a dragon, such as the black people speak of in their legends. If so, it won’t leave here until we’re both dead.”

Valeria looked at him blankly, her resentment forgotten. She fought down a surging of panic. She had proved her reckless courage a thousand times in wild battles on sea and land, on the blood-slippery decks of burning war-ships, in the storming of walled cities, and on the trampled sandy beaches where the desperate men of the Red Brotherhood bathed their knives in one another’s blood in their fights for leadership. But the prospect now confronting her congealed her blood. A cutlas stroke in the heat of battle was nothing; but to sit idle and helpless on a bare rock until she perished of starvation, besieged by a monstrous survival of an elder age—the thought sent panic throbbing through her brain.

“He must leave to eat and drink,” she said helplessly.

“He won’t have to go far to do either,” Conan pointed out. “He’s just gorged on horse-meat, and like a real snake, he can go for a long time without eating or drinking again. But he doesn’t sleep after eating, like a real snake, it seems. Anyway, he can’t climb this crag.”

Conan spoke imperturbably. He was a barbarian, and the terrible patience of the wilderness and its children was as much a part of him as his lusts and rages. He could endure a situation like this with a coolness impossible to a civilized person.

“Can’t we get into the trees and get away, traveling like apes through the branches?” she asked desperately.

He shook his head. “I thought of that. The branches that touch the crag down there are too light. They’d break with our weight. Besides, I have an idea that devil could tear up any tree around here by its roots.”

“Well, are we going to sit here on our rumps until we starve, like that?” she cried furiously, kicking the skull clattering across the ledge. “I won’t do it! I’ll go down there and cut his damned head off——”

Conan had seated himself on a rocky projection at the foot of the spire. He looked up with a glint of admiration at her blazing eyes and tense, quivering figure, but, realizing that she was in just the mood for any madness, he let none of his admiration sound in his voice.

“Sit down,” he grunted, catching her by her wrist and pulling her down on his knee. She was too surprized to resist as he took her sword from her hand and shoved it back in its sheath. “Sit still and calm down. You’d only break your steel on his scales. He’d gobble you up at one gulp, or smash you like an egg with that spiked tail of his. We’ll get out of this jam some way, but we shan’t do it by getting chewed up and swallowed.”

She made no reply, nor did she seek to repulse his arm from about her waist. She was frightened, and the sensation was new to Valeria of the Red Brotherhood. So she sat on her companion’s—or captor’s—knee with a docility that would have amazed Zarallo, who had anathematized her as a she-devil out of hell’s seraglio.

Conan played idly with her curly yellow locks, seemingly intent only upon his conquest. Neither the skeleton at his feet nor the monster crouching below disturbed his mind or dulled the edge of his interest.

The girl’s restless eyes, roving the leaves below them, discovered splashes of color among the green. It was fruit, large, darkly crimson globes suspended from the boughs of a tree whose broad leaves were a peculiarly rich and vivid green. She became aware of both thirst and hunger, though thirst had not assailed her until she knew she could not descend from the crag to find food and water.

“We need not starve,” she said. “There is fruit we can reach.”

Conan glanced where she pointed.

“If we ate that we wouldn’t need the bite of a dragon,” he grunted. “That’s what the black people of Kush call the Apples of Derketa. Derketa is the Queen of the Dead. Drink a little of the juice, or spill it on your flesh, and you’d be dead before you could tumble to the foot of this crag.”

“Oh!”

She lapsed into dismayed silence. There seemed no way out of their predicament, she reflected gloomily. She saw no way of escape, and Conan seemed to be concerned only with her supple waist and curly tresses. If he was trying to formulate a plan of escape he did not show it.

“If you’ll take your hands off me long enough to climb up on that peak,” she said presently, “you’ll see something that will surprize you.”

He cast her a questioning glance, then obeyed with a shrug of his massive shoulders. Clinging to the spire-like pinnacle, he stared out over the forest roof.

He stood a long moment in silence, posed like a bronze statue on the rock.

“It’s a walled city, right enough,” he muttered presently. “Was that where you were going, when you tried to send me off alone to the coast?”

“I saw it before you came. I knew nothing of it when I left Sukhmet.”

“Who’d have thought to find a city here? I don’t believe the Stygians ever penetrated this far. Could black people build a city like that? I see no herds on the plain, no signs of cultivation, or people moving about.”

“How could you hope to see all that, at this distance?” she demanded.

He shrugged his shoulders and dropped down on the shelf.

“Well, the folk of the city can’t help us just now. And they might not, if they could. The people of the Black Countries are generally hostile to strangers. Probably stick us full of spears——”

He stopped short and stood silent, as if he had forgotten what he was saying, frowning down at the crimson spheres gleaming among the leaves.

“Spears!” he muttered. “What a blasted fool I am not to have thought of that before! That shows what a pretty woman does to a man’s mind.”

“What are you talking about?” she inquired.

Without answering her question, he descended to the belt of leaves and looked down through them. The great brute squatted below, watching the crag with the frightful patience of the reptile folk. So might one of his breed have glared up at their troglodyte ancestors, treed on a high-flung rock, in the dim dawn ages. Conan cursed him without heat, and began cutting branches, reaching out and severing them as far from the end as he could reach. The agitation of the leaves made the monster restless. He rose from his haunches and lashed his hideous tail, snapping off saplings as if they had been toothpicks. Conan watched him warily from the corner of his eye, and just as Valeria believed the dragon was about to hurl himself up the crag again, the Cimmerian drew back and climbed up to the ledge with the branches he had cut. There were three of these, slender shafts about seven feet long, but not larger than his thumb. He had also cut several strands of tough, thin vine.

“Branches too light for spear-hafts, and creepers no thicker than cords,” he remarked, indicating the foliage about the crag. “It won’t hold our weight—but there’s strength in union. That’s what the Aquilonian renegades used to tell us Cimmerians when they came into the hills to raise an army to invade their own country. But we always fight by clans and tribes.”

“What the devil has that got to do with those sticks?” she demanded.

“You wait and see.”

Gathering the sticks in a compact bundle, he wedged his poniard hilt between them at one end. Then with the vines he bound them together, and when he had completed his task, he had a spear of no small strength, with a sturdy shaft seven feet in length.

“What good will that do?” she demanded. “You told me that a blade couldn’t pierce his scales——”

“He hasn’t got scales all over him,” answered Conan. “There’s more than one way of skinning a panther.”

Moving down to the edge of the leaves, he reached the spear up and carefully thrust the blade through one of the Apples of Derketa, drawing aside to avoid the darkly purple drops that dripped from the pierced fruit. Presently he withdrew the blade and showed her the blue steel stained a dull purplish crimson.

“I don’t know whether it will do the job or not,” quoth he. “There’s enough poison there to kill an elephant, but—well, we’ll see.”

Valeria was close behind him as he let himself down among the leaves. Cautiously holding the poisoned pike away from him, he thrust his head through the branches and addressed the monster.

“What are you waiting down there for, you misbegotten offspring of questionable parents?” was one of his more printable queries. “Stick your ugly head up here again, you long-necked brute—or do you want me to come down there and kick you loose from your illegitimate spine?”

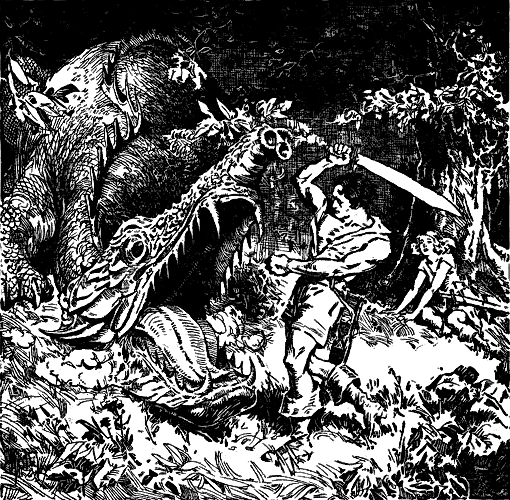

There was more of it—some of it couched in eloquence that made Valeria stare, in spite of her profane education among the seafarers. And it had its effect on the monster. Just as the incessant yapping of a dog worries and enrages more constitutionally silent animals, so the clamorous voice of a man rouses fear in some bestial bosoms and insane rage in others. Suddenly and with appalling quickness, the mastodonic brute reared up on its mighty hind legs and elongated its neck and body in a furious effort to reach this vociferous pigmy whose clamor was disturbing the primeval silence of its ancient realm.

But Conan had judged his distance with precision. Some five feet below him the mighty head crashed terribly but futilely through the leaves. And as the monstrous mouth gaped like that of a great snake, Conan drove his spear into the red angle of the jaw-bone hinge. He struck downward with all the strength of both arms, driving the long poniard blade to the hilt in flesh, sinew and bone.

Instantly the jaws clashed convulsively together, severing the triple-pieced shaft and almost precipitating Conan from his perch. He would have fallen but for the girl behind him, who caught his sword-belt in a desperate grasp. He clutched at a rocky projection, and grinned his thanks back at her.

Down on the ground the monster was wallowing like a dog with pepper in its eyes. He shook his head from side to side, pawed at it, and opened his mouth repeatedly to its widest extent. Presently he got a huge front foot on the stump of the shaft and managed to tear the blade out. Then he threw up his head, jaws wide and spouting blood, and glared up at the crag with such concentrated and intelligent fury that Valeria trembled and drew her sword. The scales along his back and flanks turned from rusty brown to a dull lurid red. Most horribly the monster’s silence was broken. The sounds that issued from his blood-streaming jaws did not sound like anything that could have been produced by an earthly creation.

With harsh, grating roars, the dragon hurled himself at the crag that was the citadel of his enemies. Again and again his mighty head crashed upward through the branches, snapping vainly on empty air. He hurled his full ponderous weight against the rock until it vibrated from base to crest. And rearing upright he gripped it with his front legs like a man and tried to tear it up by the roots, as if it had been a tree.

This exhibition of primordial fury chilled the blood in Valeria’s veins, but Conan was too close to the primitive himself to feel anything but a comprehending interest. To the barbarian, no such gulf existed between himself and other men, and the animals, as existed in the conception of Valeria. The monster below them, to Conan, was merely a form of life differing from himself mainly in physical shape. He attributed to it characteristics similar to his own, and saw in its wrath a counterpart of his rages, in its roars and bellowings merely reptilian equivalents to the curses he had bestowed upon it. Feeling a kinship with all wild things, even dragons, it was impossible for him to experience the sick horror which assailed Valeria at the sight of the brute’s ferocity.

He sat watching it tranquilly, and pointed out the various changes that were taking place in its voice and actions.

“The poison’s taking hold,” he said with conviction.

“I don’t believe it.” To Valeria it seemed preposterous to suppose that anything, however lethal, could have any effect on that mountain of muscle and fury.

“There’s pain in his voice,” declared Conan. “First he was merely angry because of the stinging in his jaw. Now he feels the bite of the poison. Look! He’s staggering. He’ll be blind in a few more minutes. What did I tell you?”

For suddenly the dragon had lurched about and went crashing off through the bushes.

“Is he running away?” inquired Valeria uneasily.

“He’s making for the pool!” Conan sprang up, galvanized into swift activity. “The poison makes him thirsty. Come on! He’ll be blind in a few moments, but he can smell his way back to the foot of the crag, and if our scent’s here still, he’ll sit there until he dies. And others of his kind may come at his cries. Let’s go!”

“Down there?” Valeria was aghast.

“Sure! We’ll make for the city! They may cut our heads off there, but it’s our only chance. We may run into a thousand more dragons on the way, but it’s sure death to stay here. If we wait until he dies, we may have a dozen more to deal with. After me, in a hurry!”

He went down the ramp as swiftly as an ape, pausing only to aid his less agile companion, who, until she saw the Cimmerian climb, had fancied herself the equal of any man in the rigging of a ship or on the sheer face of a cliff.

They descended into the gloom below the branches and slid to the ground silently, though Valeria felt as if the pounding of her heart must surely be heard from far away. A noisy gurgling and lapping beyond the dense thicket indicated that the dragon was drinking at the pool.

“As soon as his belly is full he’ll be back,” muttered Conan. “It may take hours for the poison to kill him—if it does at all.”

Somewhere beyond the forest the sun was sinking to the horizon. The forest was a misty twilight place of black shadows and dim vistas. Conan gripped Valeria’s wrist and glided away from the foot of the crag. He made less noise than a breeze blowing among the tree-trunks, but Valeria felt as if her soft boots were betraying their flight to all the forest.

“I don’t think he can follow a trail,” muttered Conan. “But if a wind blew our body-scent to him, he could smell us out.”

“Mitra grant that the wind blow not!” Valeria breathed.

Her face was a pallid oval in the gloom. She gripped her sword in her free hand, but the feel of the shagreen-bound hilt inspired only a feeling of helplessness in her.

They were still some distance from the edge of the forest when they heard a snapping and crashing behind them. Valeria bit her lip to check a cry.

“He’s on our trail!” she whispered fiercely.

Conan shook his head.

“He didn’t smell us at the rock, and he’s blundering about through the forest trying to pick up our scent. Come on! It’s the city or nothing now! He could tear down any tree we’d climb. If only the wind stays down——”

They stole on until the trees began to thin out ahead of them. Behind them the forest was a black impenetrable ocean of shadows. The ominous crackling still sounded behind them, as the dragon blundered in his erratic course.

“There’s the plain ahead,” breathed Valeria. “A little more and we’ll——”

“Crom!” swore Conan.

“Mitra!” whispered Valeria.

Out of the south a wind had sprung up.

It blew over them directly into the black forest behind them. Instantly a horrible roar shook the woods. The aimless snapping and crackling of the bushes changed to a sustained crashing as the dragon came like a hurricane straight toward the spot from which the scent of his enemies was wafted.

“Run!” snarled Conan, his eyes blazing like those of a trapped wolf. “It’s all we can do!”

Sailors’ boots are not made for sprinting, and the life of a pirate does not train one for a runner. Within a hundred yards Valeria was panting and reeling in her gait, and behind them the crashing gave way to a rolling thunder as the monster broke out of the thickets and into the more open ground.

Conan’s iron arm about the woman’s waist half lifted her; her feet scarcely touched the earth as she was borne along at a speed she could never have attained herself. If he could keep out of the beast’s way for a bit, perhaps that betraying wind would shift—but the wind held, and a quick glance over his shoulder showed Conan that the monster was almost upon them, coming like a war-galley in front of a hurricane. He thrust Valeria from him with a force that sent her reeling a dozen feet to fall in a crumpled heap at the foot of the nearest tree, and the Cimmerian wheeled in the path of the thundering titan.

“Convinced that his death was upon him, the Cimmerian acted according to his instinct.”

Convinced that his death was upon him, the Cimmerian acted according to his instinct, and hurled himself full at the awful face that was bearing down on him. He leaped, slashing like a wildcat, felt his sword cut deep into the scales that sheathed the mighty snout—and then a terrific impact knocked him rolling and tumbling for fifty feet with all the wind and half the life battered out of him.

How the stunned Cimmerian regained his feet, not even he could have ever told. But the only thought that filled his brain was of the woman lying dazed and helpless almost in the path of the hurtling fiend, and before the breath came whistling back into his gullet he was standing over her with his sword in his hand.

She lay where he had thrown her, but she was struggling to a sitting posture. Neither tearing tusks nor trampling feet had touched her. It had been a shoulder or front leg that struck Conan, and the blind monster rushed on, forgetting the victims whose scent it had been following, in the sudden agony of its death throes. Headlong on its course it thundered until its low-hung head crashed into a gigantic tree in its path. The impact tore the tree up by the roots and must have dashed the brains from the misshapen skull. Tree and monster fell together, and the dazed humans saw the branches and leaves shaken by the convulsions of the creature they covered—and then grow quiet.

Conan lifted Valeria to her feet and together they started away at a reeling run. A few moments later they emerged into the still twilight of the treeless plain.

Conan paused an instant and glanced back at the ebon fastness behind them. Not a leaf stirred, nor a bird chirped. It stood as silent as it must have stood before Man was created.

“Come on,” muttered Conan, taking his companion’s hand. “It’s touch and go now. If more dragons come out of the woods after us——”

He did not have to finish the sentence.

The city looked very far away across the plain, farther than it had looked from the crag. Valeria’s heart hammered until she felt as if it would strangle her. At every step she expected to hear the crashing of the bushes and see another colossal nightmare bearing down upon them. But nothing disturbed the silence of the thickets.

With the first mile between them and the woods, Valeria breathed more easily. Her buoyant self-confidence began to thaw out again. The sun had set and darkness was gathering over the plain, lightened a little by the stars that made stunted ghosts out of the cactus growths.

“No cattle, no plowed fields,” muttered Conan. “How do these people live?”

“Perhaps the cattle are in pens for the night,” suggested Valeria, “and the fields and grazing-pastures are on the other side of the city.”

“Maybe,” he grunted. “I didn’t see any from the crag, though.”

The moon came up behind the city, etching walls and towers blackly in the yellow glow. Valeria shivered. Black against the moon the strange city had a somber, sinister look.

Perhaps something of the same feeling occurred to Conan, for he stopped, glanced about him, and grunted: “We stop here. No use coming to their gates in the night. They probably wouldn’t let us in. Besides, we need rest, and we don’t know how they’ll receive us. A few hours’ sleep will put us in better shape to fight or run.”

He led the way to a bed of cactus which grew in a circle—a phenomenon common to the southern desert. With his sword he chopped an opening, and motioned Valeria to enter.

“We’ll be safe from snakes here, anyhow.”

She glanced fearfully back toward the black line that indicated the forest some six miles away.

“Suppose a dragon comes out of the woods?”

“We’ll keep watch,” he answered, though he made no suggestion as to what they would do in such an event. He was staring at the city, a few miles away. Not a light shone from spire or tower. A great black mass of mystery, it reared cryptically against the moonlit sky.

“Lie down and sleep. I’ll keep the first watch.”

She hesitated, glancing at him uncertainly, but he sat down cross-legged in the opening, facing toward the plain, his sword across his knees, his back to her. Without further comment she lay down on the sand inside the spiky circle.

“Wake me when the moon is at its zenith,” she directed.

He did not reply nor look toward her. Her last impression, as she sank into slumber, was of his muscular figure, immobile as a statue hewn out of bronze, outlined against the low-hanging stars.

Valeria awoke with a start, to the realization that a gray dawn was stealing over the plain.

She sat up, rubbing her eyes. Conan squatted beside the cactus, cutting off the thick pears and dexterously twitching out the spikes.

“You didn’t awake me,” she accused. “You let me sleep all night!”

“You were tired,” he answered. “Your posterior must have been sore, too, after that long ride. You pirates aren’t used to horseback.”

“What about yourself?” she retorted.

“I was a kozak before I was a pirate,” he answered. “They live in the saddle. I snatch naps like a panther watching beside the trail for a deer to come by. My ears keep watch while my eyes sleep.”

And indeed the giant barbarian seemed as much refreshed as if he had slept the whole night on a golden bed. Having removed the thorns, and peeled off the tough skin, he handed the girl a thick, juicy cactus leaf.

“Skin your teeth in that pear. It’s food and drink to a desert man. I was a chief of the Zuagirs once—desert men who live by plundering the caravans.”

“Is there anything you haven’t been?” inquired the girl, half in derision and half in fascination.

“I’ve never been king of an Hyborian kingdom,” he grinned, taking an enormous mouthful of cactus. “But I’ve dreamed of being even that. I may be too, some day. Why shouldn’t I?”

She shook her head in wonder at his calm audacity, and fell to devouring her pear. She found it not unpleasing to the palate, and full of cool and thirst-satisfying juice. Finishing his meal, Conan wiped his hands in the sand, rose, ran his fingers through his thick black mane, hitched at his sword-belt and said:

“Well, let’s go. If the people in that city are going to cut our throats they may as well do it now, before the heat of the day begins.”

His grim humor was unconscious, but Valeria reflected that it might be prophetic. She too hitched her sword-belt as she rose. Her terrors of the night were past. The roaring dragons of the distant forest were like a dim dream. There was a swagger in her stride as she moved off beside the Cimmerian. Whatever perils lay ahead of them, their foes would be men. And Valeria of the Red Brotherhood had never seen the face of the man she feared.

Conan glanced down at her as she strode along beside him with her swinging stride that matched his own.

“You walk more like a hillman than a sailor,” he said. “You must be an Aquilonian. The suns of Darfar never burnt your white skin brown. Many a princess would envy you.”

“I am from Aquilonia,” she replied. His compliments no longer irritated her. His evident admiration pleased her. For another man to have kept her watch while she slept would have angered her; she had always fiercely resented any man’s attempting to shield or protect her because of her sex. But she found a secret pleasure in the fact that this man had done so. And he had not taken advantage of her fright and the weakness resulting from it. After all, she reflected, her companion was no common man.

The sun rose behind the city, turning the towers to a sinister crimson.

“Black last night against the moon,” grunted Conan, his eyes clouding with the abysmal superstition of the barbarian. “Blood-red as a threat of blood against the sun this dawn. I do not like this city.”

But they went on, and as they went Conan pointed out the fact that no road ran to the city from the north.

“No cattle have trampled the plain on this side of the city,” said he. “No plowshare has touched the earth for years, maybe centuries. But look: once this plain was cultivated.”

Valeria saw the ancient irrigation ditches he indicated, half filled in places, and overgrown with cactus. She frowned with perplexity as her eyes swept over the plain that stretched on all sides of the city to the forest edge, which marched in a vast, dim ring. Vision did not extend beyond that ring.

She looked uneasily at the city. No helmets or spear-heads gleamed on battlements, no trumpets sounded, no challenge rang from the towers. A silence as absolute as that of the forest brooded over the walls and minarets.

The sun was high above the eastern horizon when they stood before the great gate in the northern wall, in the shadow of the lofty rampart. Rust flecked the iron bracings of the mighty bronze portal. Spiderwebs glistened thickly on hinge and sill and bolted panel.

“It hasn’t been opened for years!” exclaimed Valeria.

“A dead city,” grunted Conan. “That’s why the ditches were broken and the plain untouched.”

“But who built it? Who dwelt here? Where did they go? Why did they abandon it?”

“Who can say? Maybe an exiled clan of Stygians built it. Maybe not. It doesn’t look like Stygian architecture. Maybe the people were wiped out by enemies, or a plague exterminated them.”

“In that case their treasures may still be gathering dust and cobwebs in there,” suggested Valeria, the acquisitive instincts of her profession waking in her; prodded, too, by feminine curiosity. “Can we open the gate? Let’s go in and explore a bit.”

Conan eyed the heavy portal dubiously, but placed his massive shoulder against it and thrust with all the power of his muscular calves and thighs. With a rasping screech of rusty hinges the gate moved ponderously inward, and Conan straightened and drew his sword. Valeria stared over his shoulder, and made a sound indicative of surprize.

They were not looking into an open street or court as one would have expected. The opened gate, or door, gave directly into a long, broad hall which ran away and away until its vista grew indistinct in the distance. It was of heroic proportions, and the floor of a curious red stone, cut in square tiles, that seemed to smolder as if with the reflection of flames. The walls were of a shiny green material.

“Jade, or I’m a Shemite!” swore Conan.

“Not in such quantity!” protested Valeria.

“I’ve looted enough from the Khitan caravans to know what I’m talking about,” he asserted. “That’s jade!”

The vaulted ceiling was of lapis lazuli, adorned with clusters of great green stones that gleamed with a poisonous radiance.

“Green fire-stones,” growled Conan. “That’s what the people of Punt call them. They’re supposed to be the petrified eyes of those prehistoric snakes the ancients called Golden Serpents. They glow like a cat’s eyes in the dark. At night this hall would be lighted by them, but it would be a hellishly weird illumination. Let’s look around. We might find a cache of jewels.”

“Shut the door,” advised Valeria. “I’d hate to have to outrun a dragon down this hall.”

Conan grinned, and replied: “I don’t believe the dragons ever leave the forest.”

But he complied, and pointed out the broken bolt on the inner side.

“I thought I heard something snap when I shoved against it. That bolt’s freshly broken. Rust has eaten nearly through it. If the people ran away, why should it have been bolted on the inside?”

“They undoubtedly left by another door,” suggested Valeria.

She wondered how many centuries had passed since the light of outer day had filtered into that great hall through the open door. Sunlight was finding its way somehow into the hall, and they quickly saw the source. High up in the vaulted ceiling skylights were set in slot-like openings—translucent sheets of some crystalline substance. In the splotches of shadow between them, the green jewels winked like the eyes of angry cats. Beneath their feet the dully lurid floor smoldered with changing hues and colors of flame. It was like treading the floors of hell with evil stars blinking overhead.

Three balustraded galleries ran along on each side of the hall, one above the other.

“A four-storied house,” grunted Conan, “and this hall extends to the roof. It’s long as a street. I seem to see a door at the other end.”

Valeria shrugged her white shoulders.

“Your eyes are better than mine, then, though I’m accounted sharp-eyed among the sea-rovers.”

They turned into an open door at random, and traversed a series of empty chambers, floored like the hall, and with walls of the same green jade, or of marble or ivory or chalcedony, adorned with friezes of bronze, gold or silver. In the ceilings the green fire-gems were set, and their light was as ghostly and illusive as Conan had predicted. Under the witch-fire glow the intruders moved like specters.

Some of the chambers lacked this illumination, and their doorways showed black as the mouth of the Pit. These Conan and Valeria avoided, keeping always to the lighted chambers.

Cobwebs hung in the corners, but there was no perceptible accumulation of dust on the floor, or on the tables and seats of marble, jade or carnelian which occupied the chambers. Here and there were rugs of that silk known as Khitan which is practically indestructible. Nowhere did they find any windows, or doors opening into streets or courts. Each door merely opened into another chamber or hall.

“Why don’t we come to a street?” grumbled Valeria. “This place or whatever we’re in must be as big as the king of Turan’s seraglio.”

“They must not have perished of plague,” said Conan, meditating upon the mystery of the empty city. “Otherwise we’d find skeletons. Maybe it became haunted, and everybody got up and left. Maybe——”

“Maybe, hell!” broke in Valeria rudely. “We’ll never know. Look at these friezes. They portray men. What race do they belong to?”

Conan scanned them and shook his head.

“I never saw people exactly like them. But there’s the smack of the East about them—Vendhya, maybe, or Kosala.”

“Were you a king in Kosala?” she asked, masking her keen curiosity with derision.

“No. But I was a war-chief of the Afghulis who live in the Himelian mountains above the borders of Vendhya. These people favor the Kosalans. But why should Kosalans be building a city this far to west?”

The figures portrayed were those of slender, olive-skinned men and women, with finely chiseled, exotic features. They wore filmy robes and many delicate jeweled ornaments, and were depicted mostly in attitudes of feasting, dancing or love-making.

“Easterners, all right,” grunted Conan, “but from where I don’t know. They must have lived a disgustingly peaceful life, though, or they’d have scenes of wars and fights. Let’s go up that stair.”

It was an ivory spiral that wound up from the chamber in which they were standing. They mounted three flights and came into a broad chamber on the fourth floor, which seemed to be the highest tier in the building. Skylights in the ceiling illuminated the room, in which light the fire-gems winked pallidly. Glancing through the doors they saw, except on one side, a series of similarly lighted chambers. This other door opened upon a balustraded gallery that overhung a hall much smaller than the one they had recently explored on the lower floor.

“Hell!” Valeria sat down disgustedly on a jade bench. “The people who deserted this city must have taken all their treasures with them. I’m tired of wandering through these bare rooms at random.”

“All these upper chambers seem to be lighted,” said Conan. “I wish we could find a window that overlooked the city. Let’s have a look through that door over there.”

“You have a look,” advised Valeria. “I’m going to sit here and rest my feet.”

Conan disappeared through the door opposite that one opening upon the gallery, and Valeria leaned back with her hands clasped behind her head, and thrust her booted legs out in front of her. These silent rooms and halls with their gleaming green clusters of ornaments and burning crimson floors were beginning to depress her. She wished they could find their way out of the maze into which they had wandered and emerge into a street. She wondered idly what furtive, dark feet had glided over those flaming floors in past centuries, how many deeds of cruelty and mystery those winking ceiling-gems had blazed down upon.

It was a faint noise that brought her out of her reflections. She was on her feet with her sword in her hand before she realized what had disturbed her. Conan had not returned, and she knew it was not he that she had heard.

The sound had come from somewhere beyond the door that opened on to the gallery. Soundlessly in her soft leather boots she glided through it, crept across the balcony and peered down between the heavy balustrades.

A man was stealing along the hall.

The sight of a human being in this supposedly deserted city was a startling shock. Crouching down behind the stone balusters, with every nerve tingling, Valeria glared down at the stealthy figure.

The man in no way resembled the figures depicted on the friezes. He was slightly above middle height, very dark, though not negroid. He was naked but for a scanty silk clout that only partly covered his muscular hips, and a leather girdle, a hand’s breadth broad, about his lean waist. His long black hair hung in lank strands about his shoulders, giving him a wild appearance. He was gaunt, but knots and cords of muscles stood out on his arms and legs, without that fleshy padding that presents a pleasing symmetry of contour. He was built with an economy that was almost repellent.

Yet it was not so much his physical appearance as his attitude that impressed the woman who watched him. He slunk along, stooped in a semi-crouch, his head turning from side to side. He grasped a wide-tipped blade in his right hand, and she saw it shake with the intensity of the emotion that gripped him. He was afraid, trembling in the grip of some dire terror. When he turned his head she caught the blaze of wild eyes among the lank strands of black hair.

He did not see her. On tiptoe he glided across the hall and vanished through an open door. A moment later she heard a choking cry, and then silence fell again.

Consumed with curiosity, Valeria glided along the gallery until she came to a door above the one through which the man had passed. It opened into another, smaller gallery that encircled a large chamber.

This chamber was on the third floor, and its ceiling was not so high as that of the hall. It was lighted only by the fire-stones, and their weird green glow left the spaces under the balcony in shadows.

Valeria’s eyes widened. The man she had seen was still in the chamber.

He lay face down on a dark crimson carpet in the middle of the room. His body was limp, his arms spread wide. His curved sword lay near him.

She wondered why he should lie there so motionless. Then her eyes narrowed as she stared down at the rug on which he lay. Beneath and about him the fabric showed a slightly different color, a deeper, brighter crimson.

Shivering slightly, she crouched down closer behind the balustrade, intently scanning the shadows under the overhanging gallery. They gave up no secret.

Suddenly another figure entered the grim drama. He was a man similar to the first, and he came in by a door opposite that which gave upon the hall.

His eyes glared at the sight of the man on the floor, and he spoke something in a staccato voice that sounded like “Chicmec!” The other did not move.

The man stepped quickly across the floor, bent, gripped the fallen man’s shoulder and turned him over. A choking cry escaped him as the head fell back limply, disclosing a throat that had been severed from ear to ear.

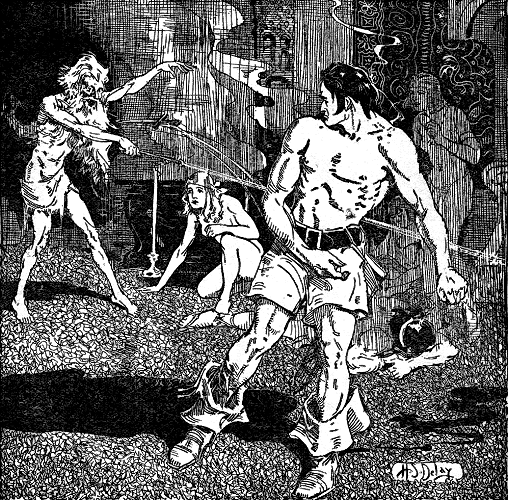

The man let the corpse fall back upon the blood-stained carpet, and sprang to his feet, shaking like a wind-blown leaf. His face was an ashy mask of fear. But with one knee flexed for flight, he froze suddenly, became as immobile as an image, staring across the chamber with dilated eyes.

In the shadows beneath the balcony a ghostly light began to glow and grow, a light that was not part of the fire-stone gleam. Valeria felt her hair stir as she watched it; for, dimly visible in the throbbing radiance, there floated a human skull, and it was from this skull—human yet appallingly misshapen—that the spectral light seemed to emanate. It hung there like a disembodied head, conjured out of night and the shadows, growing more and more distinct; human, and yet not human as she knew humanity.

The man stood motionless, an embodiment of paralyzed horror, staring fixedly at the apparition. The thing moved out from the wall and a grotesque shadow moved with it. Slowly the shadow became visible as a man-like figure whose naked torso and limbs shone whitely, with the hue of bleached bones. The bare skull on its shoulders grinned eyelessly, in the midst of its unholy nimbus, and the man confronting it seemed unable to take his eyes from it. He stood still, his sword dangling from nerveless fingers, on his face the expression of a man bound by the spells of a mesmerist.

Valeria realized that it was not fear alone that paralyzed him. Some hellish quality of that throbbing glow had robbed him of his power to think and act. She herself, safely above the scene, felt the subtle impact of a nameless emanation that was a threat to sanity.

The horror swept toward its victim and he moved at last, but only to drop his sword and sink to his knees, covering his eyes with his hands. Dumbly he awaited the stroke of the blade that now gleamed in the apparition’s hand as it reared above him like Death triumphant over mankind.

Valeria acted according to the first impulse of her wayward nature. With one tigerish movement she was over the balustrade and dropping to the floor behind the awful shape. It wheeled at the thud of her soft boots on the floor, but even as it turned, her keen blade lashed down, and a fierce exultation swept her as she felt the edge cleave solid flesh and mortal bone.

The apparition cried out gurglingly and went down, severed through shoulder, breast-bone and spine, and as it fell the burning skull rolled clear, revealing a lank mop of black hair and a dark face twisted in the convulsions of death. Beneath the horrific masquerade there was a human being, a man similar to the one kneeling supinely on the floor.

The latter looked up at the sound of the blow and the cry, and now he glared in wild-eyed amazement at the white-skinned woman who stood over the corpse with a dripping sword in her hand.

He staggered up, yammering as if the sight had almost unseated his reason. She was amazed to realize that she understood him. He was gibbering in the Stygian tongue, though in a dialect unfamiliar to her.

“Who are you? Whence come you? What do you in Xuchotl?” Then rushing on, without waiting for her to reply: “But you are a friend—goddess or devil, it makes no difference! You have slain the Burning Skull! It was but a man beneath it, after all! We deemed it a demon they conjured up out of the catacombs! Listen!”

He stopped short in his ravings and stiffened, straining his ears with painful intensity. The girl heard nothing.

“We must hasten!” he whispered. “They are west of the Great Hall! They may be all around us here! They may be creeping upon us even now!”

He seized her wrist in a convulsive grasp she found hard to break.

“Whom do you mean by ‘they’?” she demanded.

He stared at her uncomprehendingly for an instant, as if he found her ignorance hard to understand.

“They?” he stammered vaguely. “Why—why, the people of Xotalanc! The clan of the man you slew. They who dwell by the eastern gate.”

“You mean to say this city is inhabited?” she exclaimed.

“Aye! Aye!” He was writhing in the impatience of apprehension. “Come away! Come quick! We must return to Tecuhltli!”

“Where is that?” she demanded.

“The quarter by the western gate!” He had her wrist again and was pulling her toward the door through which he had first come. Great beads of perspiration dripped from his dark forehead, and his eyes blazed with terror.

“Wait a minute!” she growled, flinging off his hand. “Keep your hands off me, or I’ll split your skull. What’s all this about? Who are you? Where would you take me?”

He took a firm grip on himself, casting glances to all sides, and began speaking so fast his words tripped over each other.

“My name is Techotl. I am of Tecuhltli. I and this man who lies with his throat cut came into the Halls of Silence to try and ambush some of the Xotalancas. But we became separated and I returned here to find him with his gullet slit. The Burning Skull did it, I know, just as he would have slain me had you not killed him. But perhaps he was not alone. Others may be stealing from Xotalanc! The gods themselves blench at the fate of those they take alive!”

At the thought he shook as with an ague and his dark skin grew ashy. Valeria frowned puzzledly at him. She sensed intelligence behind this rigmarole, but it was meaningless to her.

She turned toward the skull, which still glowed and pulsed on the floor, and was reaching a booted toe tentatively toward it, when the man who called himself Techotl sprang forward with a cry.

“Do not touch it! Do not even look at it! Madness and death lurk in it. The wizards of Xotalanc understand its secret—they found it in the catacombs, where lie the bones of terrible kings who ruled in Xuchotl in the black centuries of the past. To gaze upon it freezes the blood and withers the brain of a man who understands not its mystery. To touch it causes madness and destruction.”

She scowled at him uncertainly. He was not a reassuring figure, with his lean, muscle-knotted frame, and snaky locks. In his eyes, behind the glow of terror, lurked a weird light she had never seen in the eyes of a man wholly sane. Yet he seemed sincere in his protestations.

“Come!” he begged, reaching for her hand, and then recoiling as he remembered her warning. “You are a stranger. How you came here I do not know, but if you were a goddess or a demon, come to aid Tecuhltli, you would know all the things you have asked me. You must be from beyond the great forest, whence our ancestors came. But you are our friend, or you would not have slain my enemy. Come quickly, before the Xotalancas find us and slay us!”

From his repellent, impassioned face she glanced to the sinister skull, smoldering and glowing on the floor near the dead man. It was like a skull seen in a dream, undeniably human, yet with disturbing distortions and malformations of contour and outline. In life the wearer of that skull must have presented an alien and monstrous aspect. Life? It seemed to possess some sort of life of its own. Its jaws yawned at her and snapped together. Its radiance grew brighter, more vivid, yet the impression of nightmare grew too; it was a dream; all life was a dream—it was Techotl’s urgent voice which snapped Valeria back from the dim gulfs whither she was drifting.

“Do not look at the skull! Do not look at the skull!” It was a far cry from across unreckoned voids.

Valeria shook herself like a lion shaking his mane. Her vision cleared. Techotl was chattering: “In life it housed the awful brain of a king of magicians! It holds still the life and fire of magic drawn from outer spaces!”

With a curse Valeria leaped, lithe as a panther, and the skull crashed to flaming bits under her swinging sword. Somewhere in the room, or in the void, or in the dim reaches of her consciousness, an inhuman voice cried out in pain and rage.

Techotl’s hand was plucking at her arm and he was gibbering: “You have broken it! You have destroyed it! Not all the black arts of Xotalanc can rebuild it! Come away! Come away quickly, now!”

“But I can’t go,” she protested. “I have a friend somewhere near by——”

The flare of his eyes cut her short as he stared past her with an expression grown ghastly. She wheeled just as four men rushed through as many doors, converging on the pair in the center of the chamber.

They were like the others she had seen, the same knotted muscles bulging on otherwise gaunt limbs, the same lank blue-black hair, the same mad glare in their wide eyes. They were armed and clad like Techotl, but on the breast of each was painted a white skull.

There were no challenges or war-cries. Like blood-mad tigers the men of Xotalanc sprang at the throats of their enemies. Techotl met them with the fury of desperation, ducked the swipe of a wide-headed blade, and grappled with the wielder, and bore him to the floor where they rolled and wrestled in murderous silence.

The other three swarmed on Valeria, their weird eyes red as the eyes of mad dogs.

She killed the first who came within reach before he could strike a blow, her long straight blade splitting his skull even as his own sword lifted for a stroke. She side-stepped a thrust, even as she parried a slash. Her eyes danced and her lips smiled without mercy. Again she was Valeria of the Red Brotherhood, and the hum of her steel was like a bridal song in her ears.

Her sword darted past a blade that sought to parry, and sheathed six inches of its point in a leather-guarded midriff. The man gasped agonizedly and went to his knees, but his tall mate lunged in, in ferocious silence, raining blow on blow so furiously that Valeria had no opportunity to counter. She stepped back coolly, parrying the strokes and watching for her chance to thrust home. He could not long keep up that flailing whirlwind. His arm would tire, his wind would fail; he would weaken, falter, and then her blade would slide smoothly into his heart. A sidelong glance showed her Techotl kneeling on the breast of his antagonist and striving to break the other’s hold on his wrist and to drive home a dagger.

Sweat beaded the forehead of the man facing her, and his eyes were like burning coals. Smite as he would, he could not break past nor beat down her guard. His breath came in gusty gulps, his blows began to fall erratically. She stepped back to draw him out—and felt her thighs locked in an iron grip. She had forgotten the wounded man on the floor.

Crouching on his knees, he held her with both arms locked about her legs, and his mate croaked in triumph and began working his way around to come at her from the left side. Valeria wrenched and tore savagely, but in vain. She could free herself of this clinging menace with a downward flick of her sword, but in that instant the curved blade of the tall warrior would crash through her skull. The wounded man began to worry at her bare thigh with his teeth like a wild beast.

She reached down with her left hand and gripped his long hair, forcing his head back so that his white teeth and rolling eyes gleamed up at her. The tall Xotalanc cried out fiercely and leaped in, smiting with all the fury of his arm. Awkwardly she parried the stroke, and it beat the flat of her blade down on her head so that she saw sparks flash before her eyes, and staggered. Up went the sword again, with a low, beast-like cry of triumph—and then a giant form loomed behind the Xotalanc and steel flashed like a jet of blue lightning. The cry of the warrior broke short and he went down like an ox beneath the pole-ax, his brains gushing from his skull that had been split to the throat.

“Conan!” gasped Valeria. In a gust of passion she turned on the Xotalanc whose long hair she still gripped in her left hand. “Dog of hell!” Her blade swished as it cut the air in an upswinging arc with a blur in the middle, and the headless body slumped down, spurting blood. She hurled the severed head across the room.

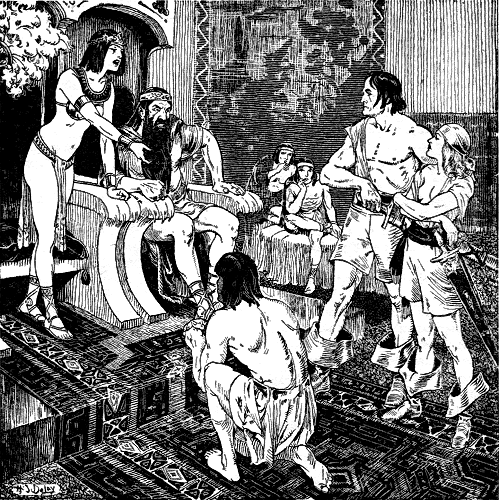

“What the devil’s going on here?” Conan bestrode the corpse of the man he had killed, broadsword in hand, glaring about him in amazement.

Techotl was rising from the twitching figure of the last Xotalanc, shaking red drops from his dagger. He was bleeding from the stab deep in the thigh. He stared at Conan with dilated eyes.

“What is all this?” Conan demanded again, not yet recovered from the stunning surprize of finding Valeria engaged in a savage battle with these fantastic figures in a city he had thought empty and uninhabited. Returning from an aimless exploration of the upper chambers to find Valeria missing from the room where he had left her, he had followed the sounds of strife that burst on his dumfounded ears.

“Five dead dogs!” exclaimed Techotl, his flaming eyes reflecting a ghastly exultation. “Five slain! Five crimson nails for the black pillar! The gods of blood be thanked!”

He lifted quivering hands on high, and then, with the face of a fiend, he spat on the corpses and stamped on their faces, dancing in his ghoulish glee. His recent allies eyed him in amazement, and Conan asked, in the Aquilonian tongue: “Who is this madman?”

Valeria shrugged her shoulders.

“He says his name’s Techotl. From his babblings I gather that his people live at one end of this crazy city, and these others at the other end. Maybe we’d better go with him. He seems friendly, and it’s easy to see that the other clan isn’t.”

Techotl had ceased his dancing and was listening again, his head tilted sidewise, dog-like, triumph struggling with fear in his repellent countenance.

“Come away, now!” he whispered. “We have done enough! Five dead dogs! My people will welcome you! They will honor you! But come! It is far to Tecuhltli. At any moment the Xotalancas may come on us in numbers too great even for your swords.”

“Lead the way,” grunted Conan.

Techotl instantly mounted a stair leading up to the gallery, beckoning them to follow him, which they did, moving rapidly to keep on his heels. Having reached the gallery, he plunged into a door that opened toward the west, and hurried through chamber after chamber, each lighted by skylights or green fire-jewels.

“What sort of a place can this be?” muttered Valeria under her breath.

“Crom knows!” answered Conan. “I’ve seen his kind before, though. They live on the shores of Lake Zuad, near the border of Kush. They’re a sort of mongrel Stygians, mixed with another race that wandered into Stygia from the east some centuries ago and were absorbed by them. They’re called Tlazitlans. I’m willing to bet it wasn’t they who built this city, though.”

Techotl’s fear did not seem to diminish as they drew away from the chamber where the dead men lay. He kept twisting his head on his shoulder to listen for sounds of pursuit, and stared with burning intensity into every doorway they passed.

Valeria shivered in spite of herself. She feared no man. But the weird floor beneath her feet, the uncanny jewels over her head, dividing the lurking shadows among them, the stealth and terror of their guide, impressed her with a nameless apprehension, a sensation of lurking, inhuman peril.

“They may be between us and Tecuhltli!” he whispered once. “We must beware lest they be lying in wait!”

“Why don’t we get out of this infernal palace, and take to the streets?” demanded Valeria.

“There are no streets in Xuchotl,” he answered. “No squares nor open courts. The whole city is built like one giant palace under one great roof. The nearest approach to a street is the Great Hall which traverses the city from the north gate to the south gate. The only doors opening into the outer world are the city gates, through which no living man has passed for fifty years.”

“How long have you dwelt here?” asked Conan.

“I was born in the castle of Tecuhltli thirty-five years ago. I have never set foot outside the city. For the love of the gods, let us go silently! These halls may be full of lurking devils. Olmec shall tell you all when we reach Tecuhltli.”

So in silence they glided on with the green fire-stones blinking overhead and the flaming floors smoldering under their feet, and it seemed to Valeria as if they fled through hell, guided by a dark-faced, lank-haired goblin.

Yet it was Conan who halted them as they were crossing an unusually wide chamber. His wilderness-bred ears were keener even than the ears of Techotl, whetted though these were by a lifetime of warfare in those silent corridors.

“You think some of your enemies may be ahead of us, lying in ambush?”

“They prowl through these rooms at all hours,” answered Techotl, “as do we. The halls and chambers between Tecuhltli and Xotalanc are a disputed region, owned by no man. We call it the Halls of Silence. Why do you ask?”

“Because men are in the chambers ahead of us,” answered Conan. “I heard steel clink against stone.”

Again a shaking seized Techotl, and he clenched his teeth to keep them from chattering.

“Perhaps they are your friends,” suggested Valeria.

“We dare not chance it,” he panted, and moved with frenzied activity. He turned aside and glided through a doorway on the left which led into a chamber from which an ivory staircase wound down into darkness.

“This leads to an unlighted corridor below us!” he hissed, great beads of perspiration standing out on his brow. “They may be lurking there, too. It may all be a trick to draw us into it. But we must take the chance that they have laid their ambush in the rooms above. Come swiftly, now!”

Softly as phantoms they descended the stair and came to the mouth of a corridor black as night. They crouched there for a moment, listening, and then melted into it. As they moved along, Valeria’s flesh crawled between her shoulders in momentary expectation of a sword-thrust in the dark. But for Conan’s iron fingers gripping her arm she had no physical cognizance of her companions. Neither made as much noise as a cat would have made. The darkness was absolute. One hand, outstretched, touched a wall, and occasionally she felt a door under her fingers. The hallway seemed interminable.

Suddenly they were galvanized by a sound behind them. Valeria’s flesh crawled anew, for she recognized it as the soft opening of a door. Men had come into the corridor behind them. Even with the thought she stumbled over something that felt like a human skull. It rolled across the floor with an appalling clatter.

“Run!” yelped Techotl, a note of hysteria in his voice, and was away down the corridor like a flying ghost.

Again Valeria felt Conan’s hand bearing her up and sweeping her along as they raced after their guide. Conan could see in the dark no better than she, but he possessed a sort of instinct that made his course unerring. Without his support and guidance she would have fallen or stumbled against the wall. Down the corridor they sped, while the swift patter of flying feet drew closer and closer, and then suddenly Techotl panted: “Here is the stair! After me, quick! Oh, quick!”

His hand came out of the dark and caught Valeria’s wrist as she stumbled blindly on the steps. She felt herself half dragged, half lifted up the winding stair, while Conan released her and turned on the steps, his ears and instincts telling him their foes were hard at their backs. And the sounds were not all those of human feet.

Something came writhing up the steps, something that slithered and rustled and brought a chill in the air with it. Conan lashed down with his great sword and felt the blade shear through something that might have been flesh and bone, and cut deep into the stair beneath. Something touched his foot that chilled like the touch of frost, and then the darkness beneath him was disturbed by a frightful thrashing and lashing, and a man cried out in agony.

The next moment Conan was racing up the winding staircase, and through a door that stood open at the head.

Valeria and Techotl were already through, and Techotl slammed the door and shot a bolt across it—the first Conan had seen since they left the outer gate.

Then he turned and ran across the well-lighted chamber into which they had come, and as they passed through the farther door, Conan glanced back and saw the door groaning and straining under heavy pressure violently applied from the other side.

Though Techotl did not abate either his speed or his caution, he seemed more confident now. He had the air of a man who has come into familiar territory, within call of friends.

But Conan renewed his terror by asking: “What was that thing that I fought on the stair?”

“The men of Xotalanc,” answered Techotl, without looking back. “I told you the halls were full of them.”

“This wasn’t a man,” grunted Conan. “It was something that crawled, and it was as cold as ice to the touch. I think I cut it asunder. It fell back on the men who were following us, and must have killed one of them in its death throes.”

Techotl’s head jerked back, his face ashy again. Convulsively he quickened his pace.

“It was the Crawler! A monster they have brought out of the catacombs to aid them! What it is, we do not know, but we have found our people hideously slain by it. In Set’s name, hasten! If they put it on our trail, it will follow us to the very doors of Tecuhltli!”

“I doubt it,” grunted Conan. “That was a shrewd cut I dealt it on the stair.”

“Hasten! Hasten!” groaned Techotl.

They ran through a series of green-lit chambers, traversed a broad hall, and halted before a giant bronze door.

Techotl said: “This is Tecuhltli!”

Techotl smote on the bronze door with his clenched hand, and then turned sidewise, so that he could watch back along the hall.

“Men have been smitten down before this door, when they thought they were safe,” he said.

“Why don’t they open the door?” asked Conan.

“They are looking at us through the Eye,” answered Techotl. “They are puzzled at the sight of you.” He lifted his voice and called: “Open the door, Xecelan! It is I, Techotl, with friends from the great world beyond the forest!—They will open,” he assured his allies.

“They’d better do it in a hurry, then,” said Conan grimly. “I hear something crawling along the floor beyond the hall.”

Techotl went ashy again and attacked the door with his fists, screaming: “Open, you fools, open! The Crawler is at our heels!”