Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

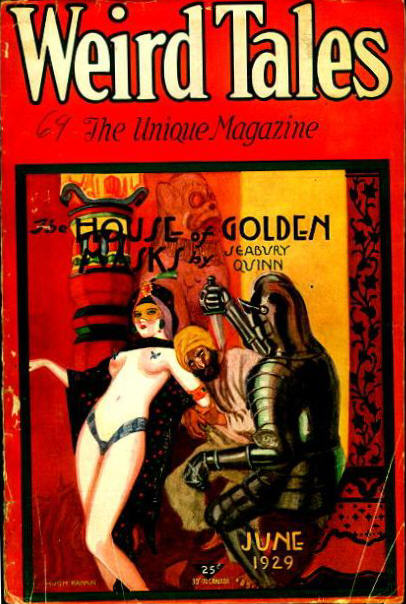

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 13, No. 6 (June 1929).

“Landlord, ho!” The shout broke the lowering silence and reverberated through the black forest with sinister echoing.

“This place hath a forbidding aspect, meseemeth.”

Two men stood in front of the forest tavern. The building was low, long and rambling, built of heavy logs. Its small windows were heavily barred and the door was closed. Above the door its sinister sign showed faintly—a cleft skull.

This door swung slowly open and a bearded face peered out. The owner of the face stepped back and motioned his guests to enter—with a grudging gesture it seemed. A candle gleamed on a table; a flame smoldered in the fireplace.

“Your names?”

“Solomon Kane,” said the taller man briefly.

“Gaston l’Armon,” the other spoke curtly. “But what is that to you?”

“Strangers are few in the Black Forest,” grunted the host, “bandits many. Sit at yonder table and I will bring food.”

The two men sat down, with the bearing of men who have traveled far. One was a tall gaunt man, clad in a featherless hat and somber black garments, which set off the dark pallor of his forbidding face. The other was of a different type entirely, bedecked with lace and plumes, although his finery was somewhat stained from travel. He was handsome in a bold way, and his restless eyes shifted from side to side, never still an instant.

The host brought wine and food to the rough-hewn table and then stood back in the shadows, like a somber image. His features, now receding into vagueness, now luridly etched in the firelight as it leaped and flickered, were masked in a beard which seemed almost animal-like in thickness. A great nose curved above this beard and two small red eyes stared unblinkingly at his guests.

“Who are you?” suddenly asked the younger man.

“I am the host of the Cleft Skull Tavern,” sullenly replied the other. His tone seemed to challenge his questioner to ask further.

“Do you have many guests?” l’Armon pursued.

“Few come twice,” the host grunted.

Kane started and glanced up straight into those small red eyes, as if he sought for some hidden meaning in the host’s words. The flaming eyes seemed to dilate, then dropped sullenly before the Englishman’s cold stare.

“I’m for bed,” said Kane abruptly, bringing his meal to a close. “I must take up my journey by daylight.”

“And I,” added the Frenchman. “Host, show us to our chambers.”

Black shadows wavered on the walls as the two followed their silent host down a long, dark hall. The stocky, broad body of their guide seemed to grow and expand in the light of the small candle which he carried, throwing a long, grim shadow behind him.

At a certain door he halted, indicating that they were to sleep there. They entered; the host lit a candle with the one he carried, then lurched back the way he had come.

In the chamber the two men glanced at each other. The only furnishings of the room were a couple of bunks, a chair or two and a heavy table.

“Let us see if there be any way to make fast the door,” said Kane. “I like not the looks of mine host.”

“There are racks on door and jamb for a bar,” said Gaston, “but no bar.”

“We might break up the table and use its pieces for a bar,” mused Kane.

“Mon Dieu,” said l’Armon, “you are timorous, m’sieu.”

Kane scowled. “I like not being murdered in my sleep,” he answered gruffly.

“My faith!” the Frenchman laughed. “We are chance met—until I overtook you on the forest road an hour before sunset, we had never seen each other.”

“I have seen you somewhere before,” answered Kane, “though I can not now recall where. As for the other, I assume every man is an honest fellow until he shows me he is a rogue; moreover, I am a light sleeper and slumber with a pistol at hand.”

The Frenchman laughed again.

“I was wondering how m’sieu could bring himself to sleep in the room with a stranger! Ha! Ha! All right, m’sieu Englishman, let us go forth and take a bar from one of the other rooms.”

Taking the candle with them, they went into the corridor. Utter silence reigned and the small candle twinkled redly and evilly in the thick darkness.

“Mine host hath neither guests nor servants,” muttered Solomon Kane. “A strange tavern! What is the name, now? These German words come not easily to me—the Cleft Skull? A bloody name, i’faith.”

They tried the rooms next to theirs, but no bar rewarded their search. At last they came to the last room at the end of the corridor. They entered. It was furnished like the rest, except that the door was provided with a small barred opening, and fastened from the outside with a heavy bolt, which was secured at one end to the door-jamb. They raised the bolt and looked in.

“There should be an outer window, but there is not,” muttered Kane. “Look!”

The floor was stained darkly. The walls and the one bunk were hacked in places, great splinters having been torn away.

“Men have died in here,” said Kane, somberly. “Is yonder not a bar fixed in the wall?”

“Aye, but ’tis made fast,” said the Frenchman, tugging at it. “The—”

A section of the wall swung back and Gaston gave a quick exclamation. A small, secret room was revealed, and the two men bent over the grisly thing that lay upon its floor.

“The skeleton of a man!” said Gaston. “And behold, how his bony leg is shackled to the floor! He was imprisoned here and died.”

“Nay,” said Kane, “the skull is cleft—methinks mine host had a grim reason for the name of his hellish tavern. This man, like us, was no doubt a wanderer who fell into the fiend’s hands.”

“Likely,” said Gaston without interest; he was engaged in idly working the great iron ring from the skeleton’s leg bones. Failing in this, he drew his sword and with an exhibition of remarkable strength cut the chain which joined the ring on the leg to a ring set deep in the log floor.

“Why should he shackle a skeleton to the floor?” mused the Frenchman. “Monbleu! ’Tis a waste of good chain. Now, m’sieu,” he ironically addressed the white heap of bones, “I have freed you and you may go where you like!”

“Have done!” Kane’s voice was deep. “No good will come of mocking the dead.”

“The dead should defend themselves,” laughed l’Armon. “Somehow, I will slay the man who kills me, though my corpse climb up forty fathoms of ocean to do it.”

Kane turned toward the outer door, closing the door of the secret room behind him. He liked not this talk which smacked of demonry and witchcraft; and he was in haste to face the host with the charge of his guilt.

As he turned, with his back to the Frenchman, he felt the touch of cold steel against his neck and knew that a pistol muzzle was pressed close beneath the base of his brain.

“Move not, m’sieu!” The voice was low and silky. “Move not, or I will scatter your few brains over the room.”

The Puritan, raging inwardly, stood with his hands in air while l’Armon slipped his pistols and sword from their sheaths.

“Now you can turn,” said Gaston, stepping back.

Kane bent a grim eye on the dapper fellow, who stood bareheaded now, hat in one hand, the other hand leveling his long pistol.

“Gaston the Butcher!” said the Englishman somberly. “Fool that I was to trust a Frenchman! You range far, murderer! I remember you now, with that cursed great hat off—I saw you in Calais some years agone.”

“Aye—and now you will see me never again. What was that?”

“Rats exploring yon skeleton,” said Kane, watching the bandit like a hawk, waiting for a single slight wavering of that black gun muzzle. “The sound was of the rattle of bones.”

“Like enough,” returned the other. “Now, M’sieu Kane, I know you carry considerable money on your person. I had thought to wait until you slept and then slay you, but the opportunity presented itself and I took it. You trick easily.”

“I had little thought that I should fear a man with whom I had broken bread,” said Kane, a deep timbre of slow fury sounding in his voice.

The bandit laughed cynically. His eyes narrowed as he began to back slowly toward the outer door. Kane’s sinews tensed involuntarily; he gathered himself like a giant wolf about to launch himself in a death leap, but Gaston’s hand was like a rock and the pistol never trembled.

“We will have no death plunges after the shot,” said Gaston. “Stand still, m’sieu; I have seen men killed by dying men, and I wish to have distance enough between us to preclude that possibility. My faith—I will shoot, you will roar and charge, but you will die before you reach me with your bare hands. And mine host will have another skeleton in his secret niche. That is, if I do not kill him myself. The fool knows me not nor I him, moreover—”

The Frenchman was in the doorway now, sighting along the barrel. The candle, which had been stuck in a niche on the wall, shed a weird and flickering light which did not extend past the doorway. And with the suddenness of death, from the darkness behind Gaston’s back, a broad, vague form rose up and a gleaming blade swept down. The Frenchman went to his knees like a butchered ox, his brains spilling from his cleft skull. Above him towered the figure of the host, a wild and terrible spectacle, still holding the hanger with which he had slain the bandit.

“Ho! ho!” he roared. “Back!”

Kane had leaped forward as Gaston fell, but the host thrust into his very face a long pistol which he held in his left hand.

“Back!” he repeated in a tigerish roar, and Kane retreated from the menacing weapon and the insanity in the red eyes.

The Englishman stood silent, his flesh crawling as he sensed a deeper and more hideous threat than the Frenchman had offered. There was something inhuman about this man, who now swayed to and fro like some great forest beast while his mirthless laughter boomed out again.

“Gaston the Butcher!” he shouted, kicking the corpse at his feet. “Ho! ho! My fine brigand will hunt no more! I had heard of this fool who roamed the Black Forest—he wished gold and he found death! Now your gold shall be mine; and more than gold—vengeance!”

“I am no foe of yours,” Kane spoke calmly.

“All men are my foes! Look—the marks on my wrists! See—the marks on my ankles! And deep in my back—the kiss of the knout! And deep in my brain, the wounds of the years of the cold, silent cells where I lay as punishment for a crime I never committed!” The voice broke in a hideous, grotesque sob.

Kane made no answer. This man was not the first he had seen whose brain had shattered amid the horrors of the terrible Continental prisons.

“But I escaped!” the scream rose triumphantly. “And here I make war on all men…. What was that?”

Did Kane see a flash of fear in those hideous eyes?

“My sorcerer is rattling his bones!” whispered the host, then laughed wildly. “Dying, he swore his very bones would weave a net of death for me. I shackled his corpse to the floor, and now, deep in the night, I hear his bare skeleton clash and rattle as he seeks to be free, and I laugh, I laugh! Ho! ho! How he yearns to rise and stalk like old King Death along these dark corridors when I sleep, to slay me in my bed!”

Suddenly the insane eyes flared hideously: “You were in that secret room, you and this dead fool! Did he talk to you?”

Kane shuddered in spite of himself. Was it insanity or did he actually hear the faint rattle of bones, as if the skeleton had moved slightly? Kane shrugged his shoulders; rats will even tug at dusty bones.

The host was laughing again. He sidled around Kane, keeping the Englishman always covered, and with his free hand opened the door. All was darkness within, so that Kane could not even see the glimmer of the bones on the floor.

“All men are my foes!” mumbled the host, in the incoherent manner of the insane. “Why should I spare any man? Who lifted a hand to my aid when I lay for years in the vile dungeons of Karlsruhe—and for a deed never proven? Something happened to my brain, then. I became as a wolf—a brother to these of the Black Forest to which I fled when I escaped.

“They have feasted, my brothers, on all who lay in my tavern—all except this one who now clashes his bones, this magician from Russia. Lest he come stalking back through the black shadows when night is over the world, and slay me—for who may slay the dead?—I stripped his bones and shackled him. His sorcery was not powerful enough to save him from me, but all men know that a dead magician is more evil than a living one. Move not, Englishman! Your bones I shall leave in this secret room beside this one, to—”

The maniac was standing partly in the doorway of the secret room, now, his weapon still menacing Kane. Suddenly he seemed to topple backward, and vanished in the darkness; and at the same instant a vagrant gust of wind swept down the outer corridor and slammed the door shut behind him. The candle on the wall flickered and went out. Kane’s groping hands, sweeping over the floor, found a pistol, and he straightened, facing the door where the maniac had vanished. He stood in the utter darkness, his blood freezing, while a hideous muffled screaming came from the secret room, intermingled with the dry, grisly rattle of fleshless bones. Then silence fell.

Kane found flint and steel and lighted the candle. Then, holding it in one hand and the pistol in the other, he opened the secret door.

“Great God!” he muttered as cold sweat formed on his body. “This thing is beyond all reason, yet with mine own eyes I see it! Two vows have here been kept, for Gaston the Butcher swore that even in death he would avenge his slaying, and his was the hand which set yon fleshless monster free. And he—”

The host of the Cleft Skull lay lifeless on the floor of the secret room, his bestial face set in lines of terrible fear; and deep in his broken neck were sunk the bare fingerbones of the sorcerer’s skeleton.