Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

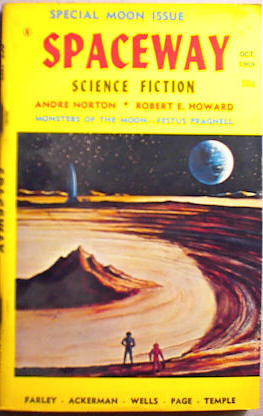

Published in Spaceway, Vol. 4, No. 3 (September-October 1969).

This comes of idle pleasure seeking and—now what prompted that thought? Some Puritanical atavism lurking in my crumbling brain, I suppose. Certainly, in my past life I never gave much heed to such teachings. At any rate, let me scribble down here my short and hideous history, before the red hour breaks and death shouts across the beaches.

There were two of us, at the start. Myself, of course, and Gloria, who was to have been my bride. Gloria had an airplane, and she loved to fly the thing—that was the beginning of the whole horror. I tried to dissuade her that day—I swear I did!—but she insisted, and we took off from Manila with Guam as our destination. Why? The whim of a reckless girl who feared nothing and always burned with the zest for some new adventure—some untried sport.

Of our coming to the Black Coast there is little to tell. One of those rare fogs rose; we soared above it and lost our way among thick billowing clouds. We struggled along, how far out of our course God alone knows, and finally fell into the sea just as we sighted land through the lifting fog.

We swam ashore from the sinking craft, unhurt, and found ourselves in a strange and forbidding land. Broad beaches sloped up from the lazy waves to end at the foot of vast cliffs. These cliffs seemed to be of solid rock and were—are—hundreds of feet high. The material was basalt or something similar. As we descended in the failing aircraft, I had had time for a quick glance shoreward, and it had seemed to me that beyond these cliffs, rose other, higher cliffs, as if in tiers, rampart above rampart. But of course, standing directly beneath the first, we could not tell. As far as we looked in either direction, we could see the narrow strip of beach running along at the foot of the black cliffs, in silent monotony.

“Now that we’re here,” said Gloria, somewhat shaken by our recent experience, “what are we to do? Where are we?”

“There isn’t any telling,” I answered. “The Pacific is full of unexplored islands. We’re probably on one. I only hope that we haven’t a gang of cannibals for neighbors.”

I wished then that I had not mentioned cannibals, but Gloria did not seem frightened at that.

“I’m not afraid of natives,” she said uneasily. “I don’t think there are any here.”

I smiled to myself, reflecting how women’s opinions merely reflected their wishes. But there was something deeper, as I soon learned in a hideous manner, and I believe now in feminine intuition. Their brain fibers are more delicate than ours—more readily disturbed and reached by psychic influences. But I had no time to theorize.

“Let’s stroll along the beach and see if we can find some way of getting up these cliffs and back on the island.”

“But the island is all cliffs, isn’t it?” she asked.

Somehow I was startled. “Why do you say that?”

“I don’t know,” she answered rather confusedly. “That was the impression I had, that this island is just a series of high cliffs, like stairs, one on top of the other, all bare black rock.”

“If that’s the case,” said I, “we’re out of luck, for we can’t live on seaweed and crabs—”

“Oh!” Her exclamation was sharp and sudden.

I caught her in my arms, rather roughly in my alarm, I fear.

“Gloria! What is it?”

“I don’t know.” Her eyes stared at me rather bewilderedly, as if she were emerging from some sort of nightmare.

“Did you see or hear anything?”

“No.” She seemed to be averse to leaving my sheltering arms. “It was something you said—no, that wasn’t it. I don’t know. People have daydreams. This must have been a nightmare.”

God help me; I laughed in my masculine complacency and said:

“You girls are a queer lot in some ways. Let’s go up the beach a way—”

“No!” she exclaimed emphatically.

“Then let’s go down the beach—”

“No, no!”

I lost patience.

“Gloria, what’s come over you? We can’t stay here all day. We’ve got to find a way to go up those cliffs and find what’s on the other side. Don’t be so foolish; it isn’t like you.”

“Don’t scold me,” she returned with a meekness strange to her. “Something seems to keep chasing at the outer edge of my mind, something that I can’t translate—do you believe in transmission of thought waves?”

I stared at her. I’d never heard her talk in this manner before.

“Do you think somebody’s trying to signal you by sending thought waves?”

“No, they’re not thoughts,” she murmured absently. “Not as I know thoughts, at least.”

Then, like a person suddenly coming out of a trance, she said:

“You go on and look for a place to go up the cliffs, while I wait here.”

I ’Gloria, I don’t like the idea. You come along—or else I’ll wait until you feel like going.”

“I don’t think I’ll ever feel that way,” she answered forlornly. “You don’t need to go out of sight; one can see a long way here. Did you ever see such black cliffs; this is a black coast, sure enough? Did you ever read Tevis Clyde Smith’s poem—‘The long black coasts of death—’ something? I can’t remember exactly.”

I felt a vague uneasiness at hearing her talk in this manner, but sought to dismiss the feeling with a shrug of my shoulders.

“I’ll find a trail up,” I said, “and maybe get something for our meal—clams or a crab—”

She shuddered violently.

“Don’t mention crabs. I’ve hated them all my life, but I didn’t realize it until you spoke. They eat dead things, don’t they? I know the Devil looks just like a monstrous crab.”

“All right,” said I, to humor her. “Stay right here; I won’t be gone long.”

“Kiss me before you go,” she said with a wistfulness that caught at my heart, I knew not why. I drew her tenderly into my arms, joying in the feel of her slim young body so vibrant with life and loveliness. She closed her eyes as I kissed her, and I noted how strangely white she seemed.

“Don’t go out of sight,” she said as I released her. A number of rough boulders dotted the beach, fallen, no doubt, from the overhanging cliff face, and on one of these she sat down.

With some misgivings, I turned to go. I went along the beach close to the great black wall which rose into the blue like a monster against the sky, and at last came to a number of unusually large boulders. Before going among these I glanced back and saw Gloria sitting where I had left her. I know my eyes softened as I looked on that slim, brave little figure—for the last time.

I wandered in among the boulders and lost sight of the beach behind me. I often wonder why I so thoughtlessly ignored her last plea. A man’s brain fabric is coarser than a woman’s, not so susceptible to outer influences. Yet I wonder if even then, pressure was being brought to bear upon me—

At any rate, I wandered along, gazing up at the towering black mass until it seemed to have a sort of mesmeric effect upon me. One who has never seen these cliffs cannot possibly form any true conception of them, nor can I breathe into my description the invisible aura of malignity which seemed to emanate from them. I say, they rose so high above me that their edges seemed to cut through the sky—that I felt like an ant crawling beneath a Babylonian wall—that their monstrous serrated faces seemed like the breasts of dusty gods of unthinkable age—this I can say, this much I can impart to you. But if any man ever reads this, let him not think that I have given a true portrait of the Black Coast. The reality of the thing lay, not in sight and sense nor even in the thoughts which they induced; but in the things you know without thinking—the feelings and the stirrings of consciousness, the faint clawings at the outer edge of the mind which are not thoughts at all—

But these things I discovered later. At the moment, I walked along like a man in a daze, almost mesmerized by the stark monotony of the black ramparts above me. At times I shook myself, blinked and looked out to sea to get rid of this mazy feeling, but even the sea seemed shadowed by the great walls. The further I went, the more threatening they seemed. My reason told me that they could not fall, but the instinct at the back of my brain whispered that they would suddenly hurtle down and crush me.

Then suddenly I found some fragments of driftwood which had washed ashore. I could have shouted my elation. The mere sight of them proved that man at least existed and that there was a world far removed from these dark and sullen cliffs, which seemed to fill the whole universe. I found a long fragment of iron attached to a piece of the wood and tore it off; if the necessity arose, it would make a very serviceable iron bludgeon. Rather heavy for the ordinary man, it is true, but in size and strength, I am no ordinary man.

At this moment, too, I decided I had gone far enough. Gloria was long out of sight and I retraced my steps hurriedly. As I went I noted a few tracks in the sand and reflected with amusement that if a spider crab, something larger than a horse, had crossed the beach here, it would make just such a track. Then I came in sight of the place where I had left Gloria and gazed along a bare and silent beach.

I had heard no scream, no cry. Utter silence had reigned as it reigned now, when I stood beside the boulder where she had sat and looked in the sand of the beach. Something small and slim and white lay there, and I dropped to my knees beside it. It was a woman’s hand, severed at the wrist, and as I saw upon the second finger the engagement ring I had placed there myself, my heart withered in my breast and the sky became a black ocean which drowned the sun.

How long I crouched over that pitiful fragment like a wounded beast, I do not know. Time ceased to be for me, and from its dying minutes was born Eternity. What are days, hours, years, to a shattered heart, to whose empty hurt each instant is an Everlasting Forever? But when I rose and reeled down to the sea edge, holding that little hand close to my hollow bosom, the sun had set and the moon had set and the hard white stars looked scornfully at me across the immensity of space.

There I pressed my lips again and again to that pitiful cold flesh and laid the slim little hand on the flowing tide which carried it out to the clean, deep sea, as I trust, merciful God, the white flame of her soul found rest in the Everlasting Sea. And the sad and ancient waves that know all the sorrows of men seemed to weep for me, for I could not weep. But since, many have shed tears, oh God, and the tears were of blood!

I staggered along the mocking whiteness of the beach like a drunken man or a lunatic. And from the time that I rose from the sighing tide to the time that I dropped exhausted and became unconscious seems centuries on countless centuries, during which I raved and screamed and staggered along huge black ramparts which frowned down on me in cold inhuman disdain—which brooded above the squeaking ant at their feet.

The sun was up when I awoke, and I found I was not alone. I sat up. On every hand I was ringed in by a strange and horrible throng. If you can imagine spider crabs larger than a horse—yet they were not true spider crabs, outside the difference in the size. Leaving that difference out, I should say that there was as much variation in these monsters and the true spider crab as there is between a highly developed European and an African bushman. These were more highly developed, if you understand me.

They sat up and looked at me. I remained motionless, uncertain just what to expect—and a cold fear began to steal over me. This was not caused by any especial fear of the brutes killing me, for I felt somehow that they would do that, and did not shrink from the thought. But their eyes bored in on me and turned my blood to ice. For in them I recognized an intelligence infinitely higher than mine, yet terribly different. This is hard to conceive, harder to explain. But as I looked into those frightful eyes, I knew that keen, powerful brains lurked behind them, brains which worked in a higher sphere, a different dimension than mine.

There was neither friendliness nor favor in those eyes, no sympathy or understanding—not even fear or hate. It is a terrible thing for a human being to be looked at in that manner. Even the eyes of a human enemy who is going to kill us have understanding in them, and a certain acceptance of kindred. But these fiends gazed upon me in something of the manner in which cold-hearted scientists might look at a worm about to be stuck on a specimen board. They did not—they could not—understand me. My thoughts, sorrows, joys, ambitions, they never could fathom, any more than I could fathom theirs. We were of different species! And no wars of humankind can ever equal in cruelty the constant warfare that is waged between living things of diverging order. Is it possible that all life came from one stem? I cannot now believe it.

There was intelligence and power in the cold eyes which were fixed on me, but not intelligence as I knew it. They had progressed much further than mankind in their ways, but they progressed along different lines. Further than this, I cannot say. Their minds and reasoning faculties are closed doors to me and most of their actions seem absolutely meaningless; yet I know that these actions are guided by definite, though inhuman, thoughts, which in turn are the results of a higher stage of development than the human race may ever reach in their way.

But as I sat there and these thoughts were borne in on me—as I felt the terrific force of their inhuman intellect crashing against my brain and will power, I leaped up, cold with fear; a wild unreasoning fear which wild beasts must feel when first confronted by men. I knew that these things were of a higher order than myself, and I feared to even threaten them, yet with all my soul I hated them.

The average man feels no compunction in his dealings with the insects underfoot. He does not feel, as he does in his dealings with his brother man, that the Higher Powers will call upon him for an accounting of the worms on which he treads, nor the fowls he eats. Nor does a lion devour a lion, yet feasts nobly on buffalo or man. I tell you, Nature is most cruel when she sets the species against each other.

These thinking crabs, then, looking upon me as God only knows what sort of prey or specimen, were intending me God only knows what sort of evil, when I broke the chain of terror which held me. The largest one, whom I faced, was now eying me with a sort of grim disapproval, a sort of anger, as if he haughtily resented my threatening actions—as a scientist might resent the writhing of a worm beneath the dissecting knife. At that, fury blazed in me and the flames were fanned by my fear. With one leap I reached the largest crab and with one desperate smash I crushed and killed him. Then bounding over his writhing form, I fled.

But I did not flee far. The thought came to me as I ran that these were they whom I sought for vengeance. Gloria—no wonder she started when I spoke the accursed name of “crab” and conceived the Devil to be in the form of a crab, when even then those fiends must have been stealing about us, tingling her sensitive thoughts with the psychic waves that flowed from their horrid brains. I turned, then, and came back a few steps, my bludgeon lifted. But the throng had bunched together, as cattle do upon the approach of a lion. Their claws were raised menacingly, and their cruel thought emanations struck me so like a power of physical force that I staggered backward and was unable to proceed against it. I knew then that in their way they feared me, for they backed slowly away toward the cliffs, ever fronting me.

My history is long, but I must shortly draw it to a close. Since that hour I have waged a fierce and merciless warfare against a race I knew to be higher in culture and intellect than I. Scientists, they are, and in some horrid experiment of theirs, Gloria must have perished. I cannot say.

This I have learned. Their city is high up among those lofty tiers of cliffs which I cannot see because of the overhanging crags of the first tier. I suppose the whole island is like that, a mere base of basaltic rock, rising to a high flung pinnacle, no doubt, this pinnacle being the last tier of innumerable tiers of rocky walls. The monsters descend by a secret way which I have only just discovered. They have hunted me, and I have hunted them.

I have found this, also: the one point in common between these beasts and the human is that the higher the race develops mentally, the less acute become the physical faculties. I, who am as much lower than they mentally as a gorilla is lower than a human professor, am as deadly in single combat with them as a gorilla would be with an unarmed professor. I am quicker, stronger, of keener senses. I possess coordinations which they do not. In a word, there is a strange reversion here—I am the wild beast and they are the civilized and developed beings. I ask no mercy and I give none. What are my wishes and desires to them? I would never have molested them, any more than an eagle molests men, had they not taken my mate. But to satisfy some selfish hunger or to evolve some useless scientific theory, they took her life and ruined mine.

And now I have been, and shall be, the wild beast with a vengeance. A wolf may wipe out a herd, a man-eating lion has destroyed a whole village of men, and I am a wolf, a lion, to the people—if I may call them that—of the Black Coast. I have lived on such clams as I have found, for I have never been able to bring myself to eat of crab flesh. And I have hunted my foes, along the beaches, by sunlight and by starlight, among the boulders, and high up in the cliffs as far as I could climb. It has not been easy, and I must shortly admit defeat. They have fought me with psychic weapons against which I have no defense, and the constant crashing of their wills against mine has weakened me terribly, mentally and physically. I have lain in wait for single enemies and have even attacked and destroyed several, but the strain has been terrific,

Their power is mainly mental, and far, far exceeds human mesmerism. At first it was easy to plunge through the enveloping thought-waves of one crab-man and kill him, but they have found weak places in my brain.

This I do not understand, but I know that of late I have gone through Hell with each battle. Their thought-tides have seemed to flow into my skull in waves of molten metal, freezing, burning, withering my brain and my soul.

I lie hidden and when one crab-man approaches, I leap and I must kill quickly, as a lion must kill a man with a rifle before the victim can aim and fire.

Nor have I always escaped physically unscathed, for only yesterday the desperate stroke of a dying crab-man’s claws tore off my left arm at the elbow. This would have killed me at one time, but now I shall live long enough to consummate my vengeance. Up there, in the higher tiers, up among the clouds where the crab city of horror broods, I must carry doom. I am a dying man—the wounds of my enemies’ strange weapons have shown me my Fate, but my left arm is bound so that I shall not bleed to death, my crumbling brain will hold together long enough, and I still have my right hand and my iron bludgeon. I have noted that at dawn the crab-people keep closer to their high cliffs, and such as I have found at that time are very easy to kill. Why, I do not know, but my lower reason tells me that these Masters are at a low ebb of vitality at dawn, for some reason.

I am writing this by the light of a low-hanging moon. Soon dawn will come, and in the darkness before dawn, I shall go up the secret trail I have found which leads to the clouds—and above. I shall find the demon city and as the east begins to redden, I shall begin the slaughter. Oh, it will be a great battle! I will crush and crash and kill, and my foes will lie in a great shattered heap, and at last I, too, shall die. Good enough. I shall be content. I have scattered death like a lion. I have littered the beaches with their corpses. Before I die I shall slay many more.

Gloria, the moon swings low. Dawn will be here soon. I do not know if you look in approval, from shadowland, on my red work of vengeance, but it has to some extent brought ease to my frozen soul. After all, these creatures and I are of different species, and it is Nature’s cruel custom that the diverging orders may never live in peace with each other. They took my mate; I take their lives.