Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

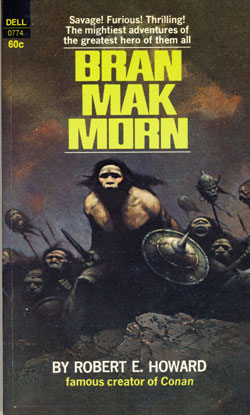

Published in Bran Mak Morn, 1969.

Thorwald Shield-hewer’s gaze wandered from the glittering menace in the hard eyes of the man who fronted him, and strayed down the length of his great skalli. He marked the long lines of mailed, horn-helmed carles, the hawk-faced chiefs who had ceased feasting to listen. And Thorwald Shield-hewer laughed.

True, the man who had just flung his defiance into the Viking’s teeth did not look particularly impressive beside the armored giants who thronged the hall. He was a short, heavily-muscled man, smooth-faced and very dark. His only garments or ornaments were rude sandals on his feet, a deerskin loincloth, and a broad leather girdle from which swung a short curiously-barbed sword. He wore no armor and his square-cut black mane was confined only by a thin silver band about his temples. His cold black eyes glittered with concentrated fury and his inner passions stirred the expressions of his usually immobile face.

“A year ago,” said he, in barbarous Norse, “you came to Golara, desiring only peace with my people. You would be our friend and protect us from the raids of others of your accursed race. We were fools; we dreamed there was faith in a sea-thief. We listened. We brought you game and fish and cut timbers when you built your steading, and shielded you from others of our people who were wiser than we. Then you were a handful with one longship. But as soon as your stockade was built, more of you came. Now your warriors number four hundred, and six dragonships are drawn up on the beach.

“Soon you became arrogant and overbearing. You insulted our chiefs, beat our young men—of late your devils have been carrying off our women and murdering our children and our warriors.”

“And what would you have me do?” cynically asked Thorwald. “I have offered to pay your chief man-bote for each warrior slain causelessly by my carles. And as for your wenches and brats—a warrior should not trouble himself about such trifles.”

“Man-bote!” the dark chief’s eyes flashed in fierce anger. “Will silver wash out spilt blood? What is silver to we of the isles? Aye—the women of other races are trifles to you Vikings, I know. But you may find that dealing thus with the girls of the forest people is far from a trifle!”

“Well,” broke in Thorwald sharply, “speak your mind and get hence. Your betters have more important affairs than listening to your clamor.”

Though the other’s eyes burned wolfishly, he made no reply to the insult.

“Go!” he answered, pointing seaward. “Back to Norge (Norway) or Hell or wherever you came from. If you will take your accursed presence hence, you may go in peace. I, Brulla, a chief of Hjaltland (Shetland Islands), have spoken.”

Thorwald leaned back and laughed deeply; his comrades echoed his laughter and the smoky rafters shook with roars of jeering mirth.

“Why, you fool,” sneered the Norseman, “do you think that Vikings ever let go of what they have taken hold? You Picts were fools enough to let us in—now we are the stronger. We of the North rule! Down on your knees, fool, and thank the fates that we allow you to live and serve us, rather than wiping out your verminous tribe altogether! But henceforth ye shall no longer be known as the Free People of Golara—nay, ye shall wear the silver collar of thralldom and men shall know ye as Thorwald’s serfs!”

The Pict’s face went livid and his self-control vanished.

“Fool!” he snarled in a voice that rang through the great hall like the grating of swords in battle. “You have sealed your doom! You Norse rule all nations, eh? Well, there be some who die, mayhap, but never serve alien masters! Remember this, you blond swine, when the forest comes to life about your walls and you see your skalli crumble in flames and rivers of blood! We of Golara were kings of the world in the long ago when your ancestors ran with wolves in the Arctic forests, and we do not bow the neck to such as you! The hounds of Doom whine at your gates and you shall die, Thorwald Shield-hewer, and you, Aslaf Jarl’s-bane, and you, Grimm Snorri’s son, and you Osric, and you, Hakon Skel, and—” the Pict’s finger, stabbing at each of the flaxen-haired chiefs in turn, wavered; the man who sat next to Hakon Skel differed strangely from the others. Not that he was a whit less wild and ferocious in his appearance. Indeed, with his dark, scarred features and narrow, cold gray eyes, he appeared more sinister than any of the rest. But he was black-haired and clean-shaven, and his mail was of the chain-mesh type forged by Irish armor-makers instead of the scale-mail of the Norse. His helmet, crested with flowing horse-hair, lay on the bench beside him.

The Pict passed over him and ended with the pronunciation of doom on the man beyond him—“And you, Hordi Raven.”

Aslaf Jarl’s-bane, a tall, evil-visaged chief, leaped to his feet: “Thor’s blood, Thorwald, are we to listen to the insolence of this jackal? I, who have been the death of a jarl in my day—”

Thorwald silenced him with a gesture. The sea-king was a yellow-bearded giant, whose eyes were those of a man used to rule. His every motion and intonation proclaimed the driving power, the ruthless strength of the man.

“You have talked much and loudly, Brulla,” he said mildly. “Mayhap you are thirsty.”

He extended a brimming drinking horn, and the Pict, thrown off guard by surprise, reached a mechanical hand for it, moving as if against his will. Then with a quick turn of his wrist, Thorwald dashed the contents full in his face. Brulla staggered with a catlike scream of hellish fury, then his sword was out like a flash of summer lightning, and he bounded at his baiter. But his eyes were blinded by the stinging ale and Thorwald’s quick-drawn sword parried his blind slashes while the Viking laughed mockingly. Then Aslaf caught up a bench and struck the Pict a terrible blow that stretched him stunned and bleeding at Thorwald’s feet. Hakon Skel drew his dagger, but Thorwald halted him.

“I’ll have no vermin’s blood polluting my skalli floor. Ho, carles, drag this carrion forth.”

The men-at-arms sprang forward with brutal eagerness. Brulla, half-senseless and bleeding, was struggling uncertainly to his knees, guided only by the wild beast fighting instinct of his race and his Age. They beat him down with shields, javelin shafts and the flat of axes, showering cruel blows on his defenseless body until he lay still. Then, jeering and jesting, they dragged him through the hall by the heels, arms trailing, and flung him contemptuously from the doorway with a kick and a curse. The Pictish chief lay face down and limply in the reddened dust, blood oozing from his pulped mouth—a symbol of the Viking’s ruthless power.

Back at the feasting board, Thorwald drained a jack of foaming ale and laughed.

“I see that we must have a Pict-harrying,” quoth he. “We must hunt these vermin out of the wood or they’ll be stealing up in the night and loosing their shafts over the stockade.”

“It will be a rare hunting!” cried Aslaf with an oath. “We cannot with honor fight such reptiles, but we can hunt them as we hunt wolves—”

“You and your vaporings of honor,” sourly growled Grimm Snorri’s son. Grimm was old, lean and cautious.

“You speak of honor and vermin,” he sneered, “but the stroke of a maddened adder can slay a king. I tell you, Thorwald, you should have used more caution in dealing with these people. They outnumber us ten to one—”

“Naked and cowardly,” replied Thorwald carelessly. “One Norseman is worth fifty such. And as for dealing with them, who is it that has been having his carles steal Pictish girls for him? Enough of your maunderings, Grimm. We have other matters to speak of.”

Old Grimm muttered in his beard and Thorwald turned to the tall, powerfully-made stranger whose dark, inscrutable face had not altered during all the recent events. Thorwald’s eyes narrowed slightly and a gleam came into them such as is seen in the eyes of a cat who plays with a mouse before devouring it.

“Partha Mac Othna,” said he, playing with the name, “it is strange that so noted a Reiver as you must be—though sooth to say, I never heard of your name before—comes to a strange steading in a small boat, alone.”

“Not so strange as it would have been had I come with a boat-load of my blood-letters,” answered the Gael. “Each of them has a half dozen blood feuds with the Norse. Had I brought them ashore, they and your carles would have been at each others’ throats ’spite all you and I could do. But we, though we fight against each other at times, need not be such fools as to forego mutual advantage because of old rivalry.”

“True, the Viking folk and the Reivers of Ireland are not friends.”

“And so, when my galley passed the lower tip of the island,” continued the Gael, “I put out in the small boat, alone, with a flag of peace, and arrived here at sundown as you know. My galley continued to Makki Head, and will pick me up at the same point I left it, at dawn.”

“So ho,” mused Thorwald, chin on fist, “and that matter of my prisoner—speak more fully, Partha Mac Othna.”

It seemed to the Gael that the Viking put undue accent on the name, but he answered: “Easy to say. My cousin Nial is captive among the Danes. My clan cannot pay the ransom they ask. It is no question of niggardliness—we have not the price they ask. But word came to us that in a sea-fight with the Danes off Helgoland you took a chief prisoner. I wish to buy him from you; we can use his captivity to force an exchange of prisoners with his tribe, perhaps.”

“The Danes are ever at war with each other, Loki’s curse on them. How know you but that my Dane is an enemy to they who hold your cousin?”

“So much the better,” grinned the Gael. “A man will pay more to get a foe in his power than he will pay for the safety of a friend.”

Thorwald toyed with his drinking horn. “True enough; you Gaels are crafty. What will you pay for this Dane—Hrut, he calls himself.”

“Five hundred pieces of silver.”

“His people would pay more.”

“Possibly. Or perhaps not a piece of copper. It is a chance we are willing to take. Besides, it will mean a long sea voyage and risks taken to communicate with them. You may have the price I offer at dawn—coin you never made more easily. My clan is not rich. The sea-kings of the North and the strong Reivers of Erin have harried we lesser wolves to the edge of the seas. But a Dane we must have, and if you are too exorbitant, why, we must sail eastward and take one by force of arms.”

“That might be easy,” mused Thorwald, “Danemark is torn by civil wars. Two kings contend against each other—or did, for I hear that Eric had the best of it, and Thorfinn fled the land.”

“Aye—so the sea-wanderers say. Thorfinn was the better man, and beloved by the people, but Eric had the support of Jarl Anlaf, the most powerful man among the Danes, not even excepting the kings themselves.”

“I heard that Thorfinn fled to the Jutes in a single ship, with a few followers,” said Thorwald. “Would that I might have met that ship on the high seas! But this Hrut will serve. I would glut my hate for the Danes on a king, but I am content with the next noblest. And noble this man is, though he wears no title. I thought him a jarl at least, in the sea-fight, when my carles lay about him in a heap waist-high. Thor’s blood, but he had a hungry sword! I made my wolves take him alive—but not for ransom. I might have wrung a greater price from his people than you offer, but more pleasant to me than the clink of gold, are the death groans of a Dane.”

“I have told you,” the Gael spread his hands helplessly. “Five hundred pieces of silver, thirty olden torts, ten Damascus swords we wrested from the brown men of Serkland (Barbary), and a suit of chain-mail armor I took from the body of a Frankish prince. More I cannot offer.”

“Yet I can scarce forego the pleasure of carving the blood-eagle in the back of this Dane,” murmured Thorwald, stroking his long, fair beard. “How will you pay this ransom—have you the silver and the rest in your garments?”

The Gael sensed the sneer in the tone, but paid no heed.

“Tomorrow at dawn you and I and the Dane will go to the lower point of the island. You may take ten men with you. While you remain on shore with the Dane, I will row out to my ship and bring back the silver and the rest, with ten of my own men. On the beach we will make the exchange. My men will remain in the boats and not even put foot ashore if you deal fairly with me.”

“Well said,” nodded Thorwald, as if pleased, yet the wolfish instinct of the Gael warned him that events were brewing. There was a gathering tension in the air. From the tail of his eye he saw the chiefs casually crowding near him. Grimm Snorri’s son’s lined, lean face was overcast and his hands twitched nervously. But no change in the Gael’s manner showed that he sensed anything out of the ordinary.

“Yet it is but a poor price to pay for a man who will be the means of restoring a great Irish prince to his clan,” Thorwald’s tone had changed; he was openly baiting the other now, “besides I think I had rather carve the blood-eagle on his back after all—and on yours as well—Cormac Mac Art!”

He spat the last words as he straightened, and his chiefs surged about him. They were not an instant too soon. They knew by reputation the lightning-like coordination of the famous Irish pirate which made his keen brain realize and his steel thews act while an ordinary man would still be gaping. Before the words were fully out of Thorwald’s mouth, Cormac was on him with a volcanic burst of motion that would have shamed a starving wolf. Only one thing saved the Shield-hewer’s life; almost as quick as Cormac he flung himself backward off the feasting bench, and the Gael’s flying sword killed a carle who stood behind it.

In an instant the flickering of swords made lightning in the smoky vastness of the skalli. It had been Cormac’s intention to hack a swift way to the door and freedom, but he was hemmed too closely by blood-lusting warriors.

Scarcely had Thorwald crashed cursing to the floor, than Cormac wheeled back to parry the word of Aslaf Jarl’s bane who loomed over him like the shadow of Doom. The Gael’s reddened blade turned Aslaf’s stroke and before the Jarl slayer could regain his balance, death flooded his throat beneath Cormac’s slicing point. A backhand stroke shore through the neckcords of a carle who was heaving up a great ax, and at the same instant Hordi Raven struck a blow that was intended to sever Cormac’s shoulder bone. But the chain-mail turned the Raven’s sword edge, and almost simultaneously Hordi was impaled on that glimmering point that seemed everywhere at once, weaving a web of death about the tall Gael. Hakon Skel, hacking at Cormac’s unhelmed head, missed by a foot and received a slash across his face, but at that instant the Gael’s feet became entangled with the corpses that littered the floor with shields and broken benches.

A concerted rush bore him back across the feasting board, where Thorwald hacked through his mail and gashed the ribs beneath. Cormac struck back desperately, shattering Thorwald’s sword and beating the sea-king to his knees beneath the shock of the blow, but a club in the hands of a powerful carle crashed down on the Gael’s unprotected head, laying the scalp open, and as he crumpled, Grimm Snorri’s son struck the sword from his hand. Then, urged by Thorwald, the carles leaped upon him, smothering and crushing the half-senseless Reiver by sheer weight of manpower. Even so, their task was not easy, but at last they had torn the steel fingers from the bull throat of one of their number, about which they had blindly locked, and bound the Gael hand and foot with cords not even his dynamic strength could break. The carle he had half-strangled gasped on the floor as they dragged Cormac upright to face the sea-king who laughed in his face.

Cormac was a grim sight. He was red-stained by the blood both of himself and his foes, and from the gash in his scalp a crimson trickle seeped down to dry on his scarred face. But his wild beast vitality already asserted itself and there was no hint of a numbed brain in the cold eyes that returned Thorwald’s domineering stare.

“Thor’s blood!” swore the sea-king. “I’m glad your comrade Wulfhere Hausakliufr—the Skull-splitter—was not with you. I have heard of your prowess as a killer, but to appreciate it, one must see for himself. In the last three minutes I have seen more weapon-play than I have seen in battles that lasted hours. By Thor, you ranged through my carles like a hunger-maddened wolf through a flock of sheep! Are all your race like you?” The Reiver deigned no reply.

“You are such a man as I would have for comrade,” said Thorwald frankly. “I will forget all old feuds if you will join me.” He spoke like a man who does not expect his wish to be granted.

Cormac’s reply was merely a glimmer of cold scorn in his icy eyes.

“Well,” said Thorwald, “I did not expect you to accede to my demand, and that spells your doom, because I cannot let such a foe to my race go free.”

Then Thorwald laughed: “Your weapon-play has not been exaggerated but your craft has. You fool—to match wits with a Viking! I knew you as soon as I laid eyes on you, though I had not seen you in years. Where on the North Seas is such a man as you, with your height, shoulder-breadth—and scarred face? I had all prepared for you, before you had ceased telling me your first lie. Bah! A chief of Irish Reivers. Aye—once, years ago. But now I know you for Cormac Mac Art an Cliun, which is to say the Wolf, righthand man of Wulfhere Hausakliufr, a Viking of the Danes. Aye, Wulfhere Hausakliufr, hated of my race.

“You desired my prisoner Hrut to trade for your cousin! Bah! I know you of old, by reputation at least. And I saw you once, years ago—you came ashore with a lie on your lips to spy out my steading, to take report of my strength and weaknesses to Wulfhere, that you and he might steal upon me some night and burn the skalli over my head.

“Well, now you can tell me—how many ships has Wulfhere and where is he?”

Cormac merely laughed, a remarkably hard contemptuous laugh that enraged Thorwald. The sea-king’s beard bristled and his eyes grew cruel.

“You will not answer me, eh?” he swore. “Well, it does not matter. Whether Wulfhere went on to Makki Head or not, three of my dragon ships will be waiting for him off the Point at dawn. Then mayhap when I carve the blood-eagle on Hrut I will have Wulfhere’s back also for my sport—and you may look on and see it well done, ere I hang you from the highest tree on Golara. To the cell with him!”

As the carles dragged Cormac away, the Gael heard the querulous, uneasy voice of Grimm Snorri’s son raised in petulant dispute with his chief. Outside the door he noted, no limp body lay in the red-stained dust. Brulla had either recovered consciousness and staggered away, or been carried away by his tribesmen.

These Picts were hard as cats to kill, Cormac knew, having fought their Caledonian cousins. A beating such as Brulla had received would have left the average man a crippled wreck, but the Pict would probably be fully recovered in a few hours, if no bones had been broken.

Thorwald Shield-hewer’s steading fronted on a small bay, on the beach of which were drawn up six long, lean ships, shield-railed and dragon-beaked. As was usual, the steading consisted of a great hall—the skalli—about which were grouped smaller buildings—stables, storehouses and the huts of the carles. Around the whole stretched a high stockade, built, like the houses, of heavy logs. The logs of the stockade were some ten feet high, set deep in the earth and sharpened on the top. There were loopholes here and there for arrows and at regularly-spaced intervals, shelves on the inner side on which the defenders might stand and strike down over the wall at the attackers. Beyond the stockade the tall dark forest loomed menacingly.

The stockade was in the form of a horseshoe with the open side seaward. The horns ran out into the shallow bay, protecting the dragon ships drawn up on the beach. An inner stockade ran straight across in front of the steading, from one horn to the other, separating the beach from the skalli. Men might swim out around the ends of the main stockade and gain the beach but they would still be blocked from the steading itself.

Thorwald’s holdings seemed well protected, but vigilance was lax. Still, the Shetlands did not swarm with sea-rovers then as they did at a later date. The few Norse holdings there were like Thorwald’s—mere pirate camps from which the Vikings swooped down on the Hebrides, the Orkneys and Britain, where the Saxons were trampling a fading Roman-Celtic civilization—and on Gaul, Spain and the Mediterranean.

Thorwald did not ordinarily expect a raid from the sea and Cormac had seen with what contempt the Vikings looked on the natives of the Shetlands. Wulfhere and his Danes were different; outlawed even among their own people, they ranged even farther than Thorwald himself, and they were keen-beaked birds of prey, whose talons tore all alike.

Cormac was dragged to a small hut built against the stockade at a point some distance from the skalli, and in this he was chained. The door slammed behind him and he was left to his meditations.

The Gael’s shallow cuts had ceased to bleed, and inured to wounds—an iron man in an Age of iron—he gave them hardly a thought. Stung vanity bothered him; how easily he had slipped into Thorwald’s trap, he whom kings had either cursed or blessed for his guile! Next time he would not be so over-confident, he mused; and a next time he was determined there should be. He did not worry overmuch about Wulfhere, even when he heard the shouts, scraping of slides, and later the clack of oars that announced that three of Thorwald’s longships were under way. Let them sneak to the Point and wait there till the dawn of Doom’s Day! Neither he nor Wulfhere had been such utter fools as to trust themselves in the power of Thorwald’s stronger force.

Wulfhere had but one ship and some eighty men. They and the ship were even now hidden securely in a forest-screened cove on the other side of the island, which was less than a mile wide at this point. There was little chance of their being discovered by Thorwald’s men and the risk of being spied out by some Pict was a chance that must be taken. If Wulfhere had followed their plan, he had run in after dark, feeling his way; there was no real reason why either Pict or Norseman should be lurking about. The shore about the cove was mainly wild, high cliffs, rugged and uninviting; moreover Cormac had heard that the Picts ordinarily avoided that part of the island because of some superstitious reason. There were ancient stone columns on the cliffs and a grim altar that hinted of ghastly rites in bygone ages.

Wulfhere would lurk there until Cormac returned to him, or until a smoke drifting up from the Point assured him that Thorwald was on hand with the prisoner and meaning no treachery. Cormac had carefully said nothing about the signal that was to bring Wulfhere, though he had not expected to be recognized for what he was. Thorwald had been wrong when he assumed that the prisoner had been used only for a blind. The Gael had lied about himself and about his reason for wishing the custody of Hrut, but it was true when he had said that it was news of the Dane’s captivity that brought him to Golara.

Cormac heard the cautious oars die away in silence. He heard the clash of arms and the shouts of the carles. Then these noises faded, all but the steady tramp of sentries, guarding against a night attack.

It must be nearly midnight, Cormac decided, glancing up at the stars gleaming through his small heavily-barred window. He was chained close to the dirt floor and could not even rise to a sitting posture. His back was against the rear wall of the hut, which was formed by the stockade, and as he reclined there, he thought he heard a sound that was not of the sighing of the night-wind through the mighty trees without. Slowly he writhed about and found himself staring through a tiny aperture between two of the upright logs.

The moon had already set; in the dim starlight he could make out the vague outline of great, gently-waving branches against the black wall of the forest. Was there a subtle whispering and rustling among those shadows that was not of the wind and the leaves? Faint and intangible as the suggestion of nameless evil, the almost imperceptible noises ran the full length of the stockade. The whole night seemed full of ghostly murmurings—as if the midnight forest were stirring and moving its darksome self, like a shadowy monster coming to uncanny life. “When the forest comes to life,” the Pict had said—

Cormac heard, within the stockade, one carle call to another. His rough voice reechoed in the whispering silence.

“Thor’s blood, the trolls must be out tonight! How the wind whispers through the trees.”

Even the dull-witted carle felt a hint of evil in the darkness and shadows. Gluing his eye to the crack, Cormac strove to pierce the darkness. The Gaelic pirate’s faculties were as much keener than the average man’s as a wolf’s are keener than a hog’s; his eyes were like a cat’s in the dark. But in that utter blackness he could see nothing but the vague forms of the first fringe of trees. Wait!

Something took shape in the shadows. A long line of figures moved like ghosts just under the shadows of the trees; a shiver passed along Cormac’s spine. Surely these creatures were elves, evil demons of the forest. Short and mightily built, half stooping, one behind the other, they passed in almost utter silence. In the shadows their silence and their crouching positions made them monstrous travesties on men. Racial memories, half lost in the misty gulfs of consciousness, came stealing back to claw with icy fingers at Cormac’s heart. He did not fear them as a man fears a human foe; it was the horror of world-old, ancestral memories that gripped him—dim felt, chaotic dream-recollections of darker Ages and grimmer days when primitive men battled for supremacy in a new world.

For these Picts were a remnant of a lost tribe—the survivals of an elder epoch—last outposts of a dark Stone Age empire that crumbled before the bronze swords of the first Celts. Now these survivors, thrust out on the naked edges of the world they had once ruled, battled grimly for their existence.

There could be no accurate counting of them because of the darkness and the swiftness of their slinking gait, but Cormac reckoned that at least four hundred passed his line of vision. That band alone was equal to Thorwald’s full strength and far outnumbered the men left in the steading now, since Thorwald had sent out three of his ships. The skulking figures passed as they had come, soundless, leaving no trace behind, like ghosts of the night.

Cormac waited in a silence that had become suddenly tense. Then without warning the night was shattered by one fearful death-yell! Pandemonium broke loose and a mad hell of sound burst on the air. And now the forest came to life! From all sides stocky figures broke cover and swarmed on the barricades. A lurid glare shed a ghastly light over all and Cormac tore savagely at his chains, wild with excitement. Monstrous events were occurring without, and here he was, chained like a sheep for the slaughter! He cursed incredibly.

The Norsemen were holding the wall; the clash of steel rose deafeningly in the night, the hum of arrows filled the air, and the deep fierce shouts of the Vikings vied with the hellish wolf-howling of the Picts. Cormac could not see, but he sensed the surging of human waves against the stockade, the plying of spears and axes, the reeling retreat and the renewed onset. The Picts, he knew, were without mail and indifferently armed. It was very possible that the limited force of Vikings could hold the stockade until Thorwald returned with the rest, as he would assuredly do when he saw the flame—but whence came the flame?

Someone was fumbling at the door. It swung open and Cormac saw the lean shambling frame and livid bearded face of Grimm Snorri’s son limned against the red glare. In one hand he held a helmet and a sword Cormac recognized as his own, in the other a bunch of keys which jangled as his hand shook.

“We are all dead men!” squawked the old Viking, “I warned Thorwald! The woods are alive with Picts! There are thousands of them! We can never hold the stockade until Thorwald returns! He is doomed too, for the Picts will cut him off when he comes into the bay and feather his men with arrows before they can come to grips! They have swum around the outer horns of the stockade and set the three remaining galleys on fire! Osric would run like a fool with a dozen carles to save the ships and he had scarcely gotten outside the gates before he was down with a score of black shafts through him and his men were cut off and hemmed in by a hundred howling demons! Not a man of them escaped, and we barely had time to shut the gates when the whole screaming mob was battering at them!

“We have slain them by the scores, but for every one that drops, three spring to take his place. I have seen more Picts tonight than I knew were on Golara—or in the world. Cormac, you are a bold man; you have a ship somewhere off the isle—swear to save me and I will set you free! Mayhap the Picts will not harm you—that devil Brulla did not name you in his death rune.

“If any man can save me it is you! I will show you where Hrut is hidden and we’ll take him with us—” he threw a quick glance over his shoulder toward the roar of battle beachward, and went white. “Thor’s blood!” he screamed, “The gates have given way and the Picts are inside the inner stockade!”

The howling rose to a crescendo of demoniac passion and fiendish exultation.

“Loose me, you gibbering fool!” raged Cormac, tearing at his chains. “You’ve time enough for babbling when—”

Chattering with fear, Grimm Snorri’s son stepped inside the hut, fumbling with the keys—even as his foot crossed the threshold a lean shape raced swift and silent as a wolf out of the flame-shot shadows. A dark arm hooked about the old Viking’s withered neck, jerking his chin up. One fearful shriek burst from his writhing lips to break short in a ghastly gurgle as a keen edge whipped across his leathery throat.

Over the twitching corpse of his victim, the Pict eyed Cormac Mac Art, and the Gael stared back, expecting death, but unafraid. Then in the glare of the burning ships, that made the cell-hut as light as day, Cormac saw that the slayer was the chief, Brulla.

“You are he who slew Aslaf and Hordi. I watched through the door of the skalli before I dragged myself away to the forests,” said the Pict, as calmly as though no inferno of combat was raging without, “I told my people of you and warned them not to harm you, if you still lived. You hate Thorwald as well as I. I will free you; glut your vengeance; soon will Thorwald return in his ships and we will cut his throat. There shall be no more Norse or Golara. All the free people of the isles here-abouts are gathering to aid us, and Thorwald is doomed!”

He bent over the Gael and released him. Cormac sprang erect, a fresh fire of confidence surging through his veins. He snatched his helmet with its flowing horsehair crest, and his long straight sword. He also took the keys from Brulla.

“Know you where was prisoned the Dane called Hrut?” he asked, as they stepped through the door. Brulla pointed across a seething whirlpool of flame and hacking swords.

“The smoke obscures the hut at present, but it lies next the storehouse on that side.”

Cormac nodded and set off at a run. Where Brulla went he neither knew nor cared. The Picts had fired stable, storehouse and skalli, as well as the ships on the beach outside the inner stockade. About the skalli and here and there close to the stockade which was also burning in a score of places, stubborn fighting went on, as the handful of survivors sold their lives with all the desperate ferocity of their breed. There were, indeed, thousands of the short, dark men, who swarmed about each tall blond warrior in a slashing, hammering mass. The heavy swords of the mailed Vikings took fearful toll, but the smaller men lashed in with a wild beast frenzy that made naught of wounds, and pulled down their giant foes by sheet weight of numbers. Once on the ground, the stabbing swords of the dark men did their work. Screams of death and yells of fury rent the flame-reddened skies, but as Cormac ran swiftly toward the storehouse, he heard no pleas for mercy. Driven to madness by countless outrages, the Picts were glutting their vengeance to the uttermost, and the Norse people neither looked nor asked for mercy.

Blond-haired women, cursing and spitting in the faces of their killers, felt the knife jerked across their white throats, and Norse babes were butchered with no more compunction than their sires had shown in the slaughter—for sport—of Pictish infants.

Cormac took no part in this holocaust. None of these people was his friend—either race would cut his throat if the chance arose. As he ran he used his sword merely to parry chance cuts that fell on him from Pict and Norseman alike, and so swiftly he moved between staggering clumps of gasping, slashing men, that he ran his way across the open space without serious opposition. He reached the hut and a few seconds’ work with the lock opened the heavy door. He had not come too soon; sparks from the burning storehouse nearby had caught on the hut thatch and already the interior was full of smoke. Through this Cormac groped his way toward a figure he could barely make out in the corner. There was a jangling of chains and a voice with a Danish accent spoke: “Slay me, in the name of Loki; better a sword thrust than this accursed smoke!”

Cormac knelt and fumbled at his chains. “I come to free you, oh Hrut,” he gasped. A moment later he dragged the astonished warrior to his feet and together they staggered out of the hut, just as the roof fell in. Drawing in great draughts of air, Cormac turned and stared curiously at his companion—a splendid, red maned giant of a man, with the bearing of a noble. He was half-naked, ragged and unkempt from weeks of captivity, but his eyes gleamed with an unconquerable light.

“A sword!” he cried, those eyes blazing as they swept the scene, “A sword, good sir, in the name of Thor! Here is a goodly brawl and we stand idle!”

Cormac stooped and tore a reddened blade from the stiffening hand of an arrow-feathered Norseman. “Here is a sword, Hrut,” he growled, “but for whom will you strike: the Norse who have kept you cooped like a caged wolf and would have slain you—or the Picts who will cut your throat because of the color of your hair?”

“There can be but little choice,” answered the Dane, “I heard the screams of women—”

“The women are all dead,” grunted the Gael. “We cannot help them now; we must save ourselves. It is the night of the wolf—and the wolves are biting!”

“I would like to cross swords with Thorwald,” the big Dane hesitated as Cormac drew him toward the flaming barrier.

“Not now, not now,” the Reiver rasped, “bigger game is afoot, Thor—Hrut! Later we will come back and finish what the Picts leave—just now we have more than ourselves to think about, for if I know Wulfhere Skullsplitter he is already marching through the woods at double-quick time!”

The stockade was in places a smoldering mass of coals; Cormac and his companion battered a way through and even as they stepped into the shadows of the trees outside, three figures rose about them and set upon them with bestial howls. Cormac shouted a warning, but it was useless. A whirling blade was at his throat and he had to strike to save himself. Turning from the corpse he had been loath to make, he saw Hrut, bestriding the mangled body of one Pict, take the barbed sword of the other in his left arm and split the wielder’s skull with an overhand stroke.

Cursing, the Gael sprang forward. “Are you badly hurt?” Blood was gushing from a deep wound in Hrut’s mighty arm.

“A scratch,” the Dane’s eyes blazed with the battle-light. But despite his protests Cormac tore a strip from his own garments and bound the arm so as to staunch the flow of blood.

“Here, help me drag these bodies under the brush,” growled the Reiver. “I hated to strike—but when they saw your red beard it was our lives or theirs. I think Brulla would see our point of view, but if the rest find we killed their brothers neither Brulla nor the devil can keep their swords from our throats.”

This done—“Listen!” commanded Hrut. The roar of battle had dwindled in the main to a crackle and roar of flames and the hideous and triumphant yelling of the Picts. Only in a single room in the flaming skalli, yet untouched by the fire, a handful of Vikings still kept up a stubborn defense. Through the noise of the fire there sounded a rhythmic clack-clack-clack!

“Thorwald is returning!” exclaimed Cormac, springing back to the edge of the forest to peer over the ruins of the stockade. Into the bay swept a single dragon ship. The long ash oars drove her plunging through the water and from her rowers and from the men massed on poop and gunwale rose a roar of deep-toned ferocity as they saw the smoking ruins of the steading and the mangled bodies of their people. From the burning skalli came an echoing shout. In the smoldering glare that turned the bay to a gulf of blood, Cormac and Hrut saw the hawk-face of Hakon Skel where he stood on the poop. But where were the other two ships? Cormac thought he knew and a smile of grim appreciation crossed his somber face.

Now the dragon-ship was sweeping in to the beach and hundreds of screaming Picts were wading out to meet it. Waist deep in water, holding their heavy black bows high to keep the cords dry, they loosed their arrows and a storm of shafts swept the dragon-ship from stem to stern. Full into the teeth of the deadliest gale it had ever faced the dragon-ship drove, while men went down in windrows along the gunwales, transfixed by the long black shafts that rent through lindenwood buckler and scale mail armor to pierce the flesh beneath.

The rest crouched behind their shields and rowed and steered as best they could. Now the keel grated on the water-flooded sand and the swarming savages closed about her. By the hundreds they scrambled up the sides, the stern and the arching prow, while others maintained a steady fire from the water and the beach. Their marksmanship was almost uncanny. Flying between two slashing Picts a long shaft would strike down a Norseman. But when it came to handgrips, the advantage was immensely with the Vikings. Their giant stature, their armor and long swords, and their position on the gunwales above their foes made them for the moment invincible.

Swords and axes rose and fell, spattering blood and brains, and stocky shapes dropped writhing from the sides of the galley to sink like stones. The water about the ship grew thick with dead, and Cormac caught his breath as he realized the lavishness with which the naked Picts were spending their lives. But soon he heard their chiefs shouting to them and he realized, as the attackers drew sullenly away, that their leaders were shouting for them to fall back and pick off the Vikings at long range.

The Vikings soon realized that also. Hakon Skel dropped with an arrow through his brain and with yells of fury the Norsemen began leaping from their ship into the water, in one desperate attempt to close with their foes and take toll in death. The Picts accepted the challenge. About each Norseman closed a dozen Picts and the bay along the beach seethed and eddied with battle. The waves grew red as blood and corpses floated thick or littered the bottom, tripping the feet and clogging the aims of the living. The warriors penned in the skalli sallied forth to die with their tribesmen.

Then what Cormac had looked for, occurred. A deep-chested roar thundered above the fury of the fight, and from the woods that fringed the bay burst Thorwald Shield-hewer, with the crews of two dragon ships at his back. Cormac knew that, guessing what had occurred, he had sent the other ship on to draw the Picts out and give him time to land below the bay and march through the forest with the rest of his men.

Now in a solid formation, shield locking shield, they swept from the woods along the shore and bore down the beach toward their foes. With howls of unquenchable fury, the Picts turned on them with a rain of shafts and a headlong charge of stocky bodies and stabbing blades. But the arrows in the main glanced from the close-lapping shields and the mob-like rush met a solid wall of iron. But with the same desperation they had shown all during the fight, the Picts hurled charge after charge on the shield-wall. It was a living sea that broke in red waves on that iron bulwark. The ground grew thick under foot with corpses, not all Pictish. But as often as a Norseman fell, his comrades locked their great shields close as ever, trampling the fallen under foot. No longer did the Vikings surge forward, but they stood like a solid rock and took not a single backward step. The wings of their wedge-shaped formation were forced inward as the Picts entirely surrounded them, until it was more like a square, facing all ways. And like a square of stone and iron it stood, and all the wild, blind charges of the Picts failed to shake it, though they hurled their bare breasts against the steel until their corpses formed a wall over which the living clambered.

Then suddenly, apparently without warning, they broke and fled in all directions, some across the flame-lit space of the steading, some into the forest. With yells of triumph the Vikings broke formation and plunged after them, though Cormac saw Thorwald screaming frantic orders and beating at his men with the flat of his reddened sword. A trick! Cormac knew it as well as Thorwald but the blind fighting frenzy of the carles betrayed them as their foes had guessed. The moment they streamed out loosely in pursuit, the Picts turned howling and a dozen Vikings went down before a hail of arrows. Before the rest could reform their position they were surrounded singly and in struggling clumps, and the work of death began. From a single massed battle, the combat became a score of single skirmishes on the beach—where the survivors of the dragon ship had made their way—before the skalli’s embers and in the fringe of the forest.

And suddenly as from a dream Cormac woke and cursed himself.

“By the blood of the gods, what a fool I am! Are we boys who have never seen a battle, to stand here gaping when we should be legging it through the forest?”

He was forced to fairly drag Hrut away, and the two ran swiftly through the forest, hearing on all sides the clangor of arms and the shouts of death. The battle had spilled over into the forest and that grim and darksome wood was the scene of many a bloody deed. But Cormac and Hrut, warned by the sounds, managed to keep clear of such struggles, though once vague figures leaped at them from the shadows, and in the blind brief whirl of battle that followed, they never knew whether it was Picts or Norsemen who fell before their swords.

Then the sounds of conflict were behind them and in front sounded the tramp of many men. Hrut stopped short, gripping his red-stained sword, but Cormac pulled him on.

“Men marching in time; they can be none but Wulfhere’s wolves!”

The next instant they burst into a glade, dimly lighted by the first whiteness of dawn, and from the opposite side strode a band of red-bearded giants, whose chief, looking like a very god of war, bellowed a welcome:

“Cormac! Thor’s blood, it seems we’ve been marching through these accursed woods forever! When I saw the glow above the trees and heard the yelling I brought every carle on the ship, for I knew not but what you were burning and looting Thorwald’s steading single handed! What is forward—and who is this?”

“This is Hrut—whom we sought,” answered Cormac. “Hell and the red whirlpools of war are what is forward—there’s blood on your axe!”

“Aye—we had to hack our way through a swarm of small, dark fellows—Picts I believe you call ’em.”

Cormac cursed. “We’ll pile up a blood-score that even Brulla can’t answer for—”

“Well,” grumbled the giant, “the woods are full of them, and we heard them howling like wolves behind us—”

“I had thought all would be at the steading,” commented Hrut.

Cormac shook his head. “Brulla spoke of a gathering of clans; they have come from all the isles of the Hjaltlands and probably landed on all sides of the island—listen!”

The clamor of battle grew louder as the fighters penetrated deeper into the mazes of the forest, but from the way Wulfhere and his Vikings had come there sounded a long-drawn yell like a pack of running wolves, swiftly rising higher and higher.

“Close ranks!” yelled Cormac, paling, and the Danes had barely time to lock their shields before the pack was upon them. Bursting from the thick trees a hundred Picts whose swords were yet unstained broke like a tidal wave on the shields of the Danes.

Cormac, thrusting and slashing like a fiend, shouted to Wulfhere: “Hold them hard—I must find Brulla. He will tell them we are foes of Thorwald and allow us to depart in peace!”

All but a handful of the original attackers were down, trodden under foot and snarling in their death throes. Cormac leaped from the shelter of the overlapping shields and darted into the forest. Searching for the Pictish chief in that battle-tortured forest was little short of madness, but it was their one lone chance. Seeing the fresh Picts coming up from behind them had told Cormac that he and his comrades would probably have to fight their way across the whole island to regain their galley. Doubtless these were warriors from some island lying to the east, who had just landed on Golara’s eastern coast.

If he could find Brulla—he had not gone a score of paces past the glade when he stumbled over two corpses, locked in a death-grapple. One was Thorwald Shield-hewer. The other was Brulla. Cormac stared at them and as the wolf-yell of the Picts rose about him, his skin crawled. Then he sprang up and ran back to the glade where he had left the Danes.

Wulfhere leaned on his great ax and stared at the corpses at his feet. His men stolidly held their position.

“Brulla is dead,” snapped the Gael. “We must aid ourselves. These Picts will cut our throats if they can, and the gods know they have no cause to love a Viking. Our only chance is to get back to our ship if we can. But that is a slim chance indeed, for I doubt not but that the woods are full of the savages. We can never keep the shield-wall position among the trees, but—”

“Think of another plan, Cormac,” said Wulfhere grimly, pointing to the east with his great ax. There a lurid glow was visible among the trees and a hideous medley of howling came faintly to their ears. There was but one answer to that red glare.

“They’ve found and fired our ship,” muttered Cormac. “By the blood of the gods, Fate’s dice are loaded against us.”

Suddenly a thought came to him.

“After me! Keep close together and hew your way through, if needs be, but follow me close!”

Without question they followed him through the corpse-strewn forest, hearing on each hand the sound of fighting men, until they stood at the forest fringe and gazed over the crumbled stockade: at the ruins of the steading. By merest chance no body of Picts had opposed their swift march, but behind them rose a frightful and vengeful clamor as a band of them came upon the corpse-littered glade the Danes had just left.

No fighting was going on among the steading’s ruins. The only Norsemen in sight were mangled corpses. The fighting had swept back into the forest whither the close-pressed Vikings had retreated or been driven. From the incessant clashing of steel within its depths, those who yet remained alive were giving a good account of themselves. Under the trees where bows were more or less useless, the survivors might defend themselves for hours, though, with the island swarming with Picts, their ultimate fate was certain.

Three or four hundred tribesmen, weary of battle at last, had left the fighting to their fresher tribesmen and were salvaging what loot they could from the embers of the storehouses.

“Look!” Cormac’s sword pointed to the dragon ship whose prow, driven in the sands, held her grounded, though her stern was afloat. “In a moment we will have a thousand yelling demons on our backs. There lies our one chance, wolves—Hakon Skel’s Raven. We must hack through and gain it, shove it free and row off before the Picts can stop us. Some of us will die, and we may all die, but it’s our only chance!

The Vikings said nothing, but their fierce light eyes blazed and many grinned wolfishly. Touch and go! Life or death on the toss of the dice! That Was a Viking’s only excuse for living!

“Lock shields!” roared Wulfhere. “Close ranks! The flying-wedge formation—Hrut in the center.”

“What—!” began Hrut angrily, but Cormac shoved him unceremoniously between the mailed ranks.

“You have no armor,” he growled impatiently. “Ready, old wolf? Then charge, and the gods choose the winners!”

Like an avalanche the steel-tipped wedge shot from the trees and raced toward the beach. The Picts looting the ruins turned with howls of amazement, and a straggling line barred the way to the water’s edge. But without slacking gait the flying shield-wall struck the Pictish line, buckled it, crumpled it, hacked it down and trampled it under, and over its red ruins rushed upon the beach.

Here the formation was unavoidably broken. Waist-deep in water, tripping among corpses, harried by the rain of arrows that now poured upon them from the beach, the Vikings gained the dragon ship and swarmed up its sides, while a dozen giants set their shoulders against the prow to push it off the sands. Half of them died in the attempt, but the titanic efforts of the rest triumphed and the galley began to give way.

The Danes were the bowmen among the Viking races. Thirty of the eighty-odd warriors who followed Wulfhere wore heavy bows and quivers of long arrows strapped to their backs. As many of these as could be spared from oars and sweeps now unslung their weapons and directed their shafts on the Picts wading into the water to attack the men at the prow. In the first light of the rising sun the Danish shafts did fearful execution, and the advance wavered and fell back. Arrows fell all about the craft and some found their marks, but crouching beneath their shields the warriors toiled mightily, and soon, though it seemed like hours, the dragon ship rolled and wallowed free, the men in the water leaped and caught at chains and gunwale, and the long oars drove her out into the bay, just as a howling horde of wolfish figures swept out of the woods and down the beach. Their arrows fell in a rain, rattling harmlessly from shield-rail and hull as the Raven shot toward the open sea.

“Touch and go!” roared Wulfhere with a great laugh, smiting Cormac terrifically between the shoulders. Hrut shook his head. To his humiliated anger, a big carle had been told off to keep a shield over him, during the fight.

“Many brave warriors are dying in yonder woods. it pains me to desert them thus, though they are our foes and would have put me to death.”

Cormac shrugged his shoulders. “I, too, would have aided them had I seen a way. But we could have accomplished naught by remaining and dying with them. By the blood of the gods, what a night this has been! Golara is rid of her Vikings, but the Picts paid a red price! All of Thorwald’s four hundred are dead now or soon will be, but not less than a thousand Picts have died outright in the steading and the gods only know how many more in the forest.”

Wulfhere glanced at Hrut where he stood on the poop, outstretched hand on the sword whose reddened point rested on the deal planking. Unkempt, bloodstained, tattered, wounded, yet still his kingly carriage was unabated.

“And now that you have rescued me so boldly against incredible odds,” said he, “what would you have of me besides my eternal gratitude, which you already have?”

Wulfhere did not reply; turning to the men who rested on their oars to gaze eagerly and expectantly up at the group on the poop, the Viking chief lifted his red axe and bellowed: “Skoal, wolves! Yell hail for Thorfinn Eaglecrest, king of Dane-mark!”

A thunderous roar went up to the blue of the morning skies that startled the wheeling sea gulls. The tattered king gasped in amazement, glancing quickly from one to the other, not yet certain of his status.

“And now that you have recognized me,” said he, “am I guest or prisoner?”

Cormac grinned. “We traced you from Skagen, whence you fled in a single ship to Helgoland, and learned there that Thorwald Shield-hewer had taken captive a Dane with the bearing of a king. Knowing you would conceal your identity, we did not expect him to know that he had a king of the Danes in his hands.

“Well, King Thorfinn, this ship and our swords are yours. We be outlaws, both from our own lands. You cannot alter my status in Erin, but you can inlaw Wulfhere and make Danish ports free to us.”

“Gladly would I do this, my friends,” said Thorfinn, deeply moved. “But how can I aid my friends, who cannot aid myself? I, too, am an outcast, and my cousin Eric rules the Danes.”

“Only until we set foot on Danish soil!” exclaimed Cormac. “Oh, Thorfinn, you fled too soon, but who can foresee the future? Even as you put to sea like a hunted pirate, the throne was rocking under Eric’s feet. While you lay captive on Thorwald’s dragon ship, Jarl Anlaf fell in battle with the Jutes and Eric lost his greatest supporter. Without Anlaf, his rule will crumble overnight and hosts will flock to your banner!”

Thorfinn’s eyes lighted with a wondrous gleam. He threw his head back as a lion throws back his mane and flung up his reddened sword into the eye of the rising sun.

“Skoal!” he cried. “Head for Dane-mark, my friends, and may Thor fill our sail!”

“Aim her prow eastward, carles,” roared Wulfhere to the men at the sweeps. “We go to set a new king on the throne of Dane-mark!”