Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

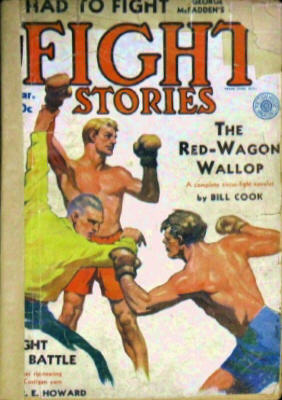

Published in Fight Stories, Vol. 4, No. 10 (March 1932).

I’m beginning to believe that Singapore is a jinx for me. Not that I don’t always get a fight there; I do. But it looks, by golly, like a lot of dirty luck is always throwed in with the fight.

Rumination of them sort was in my mind as I clumb the rickety stairs of the Seaman’s Deluxe Boarding House and entered my room, tightly gripping the fifty bucks which constituted my whole wad.

I’d just been down to see Ace Larnigan, manager of the Arena, and had got matched with Black Jack O’Brien for ten rounds or less, that night. And I was wondering where I could hide my roll. I had the choice of taking it with me and getting it stole outa my britches whilst I was in the ring, or leaving it in my room and getting it hooked by the Chino servants from which you couldn’t hide nothing.

I set on my ramshackle bed and meditated, and I had about decided to let my white bulldog, Mike, hold the roll in his mouth while I polished off Black Jack, with a good chance of him swallering it in his excitement, when all of sudden I heered sounds of somebody ascending the stairs about six steps at a jump, and then running wildly down the hall.

I paid no heed; guests of the Deluxe is always being chased into the dump or out of it by the cops. But instead of running into his own room and hiding under the bed, as was the usual custom, this particular fugitive blundered headlong against my door, blowing and gasping like a grampus. Much to my annoyance, the door was knocked violently open, and a disheveled shape fell all over the floor.

I riz with dignity. “What kind of a game is this?” I asked, with my instinctive courtesy. “Will you get outa my room or will I throw you out on your ear?”

“Hide me, Steve!” the shape gasped. “Shut the door! Hide me! Give me a gun! Call the cops! Lemme under the bed! Look out the window and see if you see anybody chasing me!”

“Make up your mind what you want me to do; I ain’t no magician,” I said disgustedly, recognizing the shape as Johnny Kyelan, a good-hearted but soft-headed sap of a kid which should of been jerking soda back home instead of trying to tend bar in a tough waterfront joint in Singapore. Just one of them fool kids which is trying to see the world.

He grabbed me with hands that shook, and I seen the sweat standing out on his face.

“You got to help me, Steve!” he babbled. “I came here because I didn’t know anybody else to go to. If you don’t help me, I’ll never live to see another sunrise. I’ve stumbled onto something I wasn’t looking for. Something that it’s certain death to know about. Steve, I’ve found out who The Black Mandarin is!”

I grunted. This is serious.

“You mean you know who it is that’s been committin’ all these robberies and murders, dressed up in a mask and Chinee clothes?”

“The same!” he exclaimed, trembling and sweating. “The worst criminal in the Orient!”

“Then why in heck don’t you go to the police?” I demanded.

He shook like he had aggers. “I don’t dare! I’d never live to get to the police station. They’re watching for me—it isn’t one man who’s been doing all these crimes; it’s a criminal organization. One man is the head, but he has a big gang. They all dress the same way when they’re robbing and looting.”

“How’d you get onto this?” I asked.

“I was tending bar,” he shuddered. “I went into the cellar to get some wine—it’s very seldom I go there. By pure chance, I came onto a group of them plotting over a table by a candle-light. I recognized them and heard them talking—the fellow who owns the saloon where I work is one of them—and I never had an inkling he was a crook. I was behind a stack of wine-kegs, and listened till I got panicky and made a break. Then they saw me. They chased me in and out among those winding alleys till I thought I’d die. I shook them off just a few minutes ago, and reached here. But I don’t dare stir out. I don’t think they saw me coming in, but they’re combing the streets, and they’d see me going out.”

“Who is the leader?” I asked.

“They call him the Chief,” he said.

“Yeah, but who is he?” I persisted, but he just shook that much more.

“I don’t dare tell.” His teeth was chattering with terror. “Somebody might be listening.”

“Well, gee whiz,” I said, “you’re in bad with ’em already—”

But he was in one of them onreasoning fears, and wouldn’t tell me nothing.

“You’d never in the world guess,” he said. “And I just don’t dare. I get goose-pimples all over when I think about it. Let me stay with you till tomorrow morning, Steve,” he begged, “then we’ll get in touch with Sir Peter Brent, the Scotland Yard guy. He’s the only man of authority I trust. The police have proven themselves helpless—nobody ever recognized one of that Mandarin gang and lived to tell about it. But Sir Peter will protect me and trap these fiends.”

“Well,” I said, “why can’t we get him now?”

“I don’t know where to reach him,” said Johnny. “He’s somewhere in Singapore—I don’t know where. But in the morning we can get him at his club; he’s always there early in the morning. For heavens’ sake, Steve, let me stay!”

“Sure, kid,” I said. “Don’t be scairt. If any them Black Mandarins comes buttin’ in here, I’ll bust ’em on the snoot. I was goin’ to fight Black Jack O’Brien down at the Arena tonight, but I’ll call it off and stick around with you.”

“No, don’t do that,” he said, beginning to get back a little of his nerve. “I’ll lock the door and stay here. I don’t think they know where I am; and, anyway, with the door locked they can’t get in to me without making a noise that would arouse the whole house. You go ahead and fight Black Jack. If you didn’t show up, some of that gang might guess you were with me; they’re men who know us both. Then that would get you into trouble. They know you’re the only friend I’ve got.”

“Well,” I said, “I’ll leave Mike here to purteck you.”

“No! No!” he said. “That’d look just as suspicious, if you showed up without Mike. Besides, they’d only shoot him if they came. You go on, and, when you come back, knock on the door and tell me who it is. I’ll know your voice and let you in.”

“Well, all right,” I said, “if you think you’ll be safe. I don’t think them Mandarins would have sense enough to figger out you was with me, just because I didn’t happen to show up at the Arena—but maybe you know. And say, you keep this fifty bucks for me. I was wonderin’ what to do with it. If I take it to the Arena, some dip will lift it offa me.”

So Johnny took it, and me and Mike started for the Arena, and, as we went down the stairs, I heered him lock the door behind us. As I left the Deluxe, I looked sharp for any slinking figgers hanging around watching the house, but didn’t see none, and went on down the street.

The arena was just off the waterfront, and it was crowded like it always is when either me or Black Jack fights. Ace had been wanting to get us together for a long time, but this was the first time we happened to be in port at the same time. I was in my dressing-room putting on my togs when in stormed a figger I knowed must be my opponent. I’ve heered it said me and Black Jack looked enough alike to be brothers; he was my height, six feet, weighed same as me, and had black hair and smoldering blue eyes. But I always figgered I was better looking than him.

I seen he was in a wicked mood, and I knowed his recent fight with Bad Bill Kearney was still rankling him. Bad Bill was a hard-boiled egg which run a gambling hall in the toughest waterfront district of Singapore and fought on the side. A few weeks before, him and O’Brien had staged a most vicious battle in the Arena, and Black Jack had been knocked cold in the fifth round, just when it looked like he was winning. It was the only time he’d ever been stopped, and, ever since, he’d been frothing at the mouth and trying to get Bad Bill back in the ring with him.

He give a snarling, blood-thirsty laugh as he seen me.

“Well, Costigan,” he said, “I guess maybe you think you’re man enough to stow me away tonight, eh? You slant-headed goriller!”

“I may not lick you, you black-jowled baboon,” I roared, suspecting a hint of insult in his manner, “but I’ll give you a tussle your great-grandchildren will shudder to hear about!”

“How strong do you believe that?” he frothed.

“Strong enough to kick your brains out here and now,” I thundered.

Ace got in between us.

“Hold it!” he requested. “I ain’t goin’ to have you boneheads rooin’in’ my show by massacreein’ each other before the fight starts.”

“What you got there?” asked O’Brien, suspiciously, as Ace dug into his pockets.

“Your dough,” said Ace sourly, bringing out a roll of bills. “I guaranteed you each fifty bucks, win, lose or draw.”

“Well,” I said, “we don’t want it now. Give it to us after the mill.”

“Ha!” sneered Ace. “Keep it and get my pockets picked? Not me! I’m givin’ it to you now. You two can take the responsibility. Here—take it! Now I’ve paid you, and you got no kick comin’ at me if you lose it. If the dips get it offa you, that ain’t my lookout.”

“All right, you white-livered land-shark,” sneered Black Jack, and turned to me. “Costigan, this fifty says I lays you like a carpet.”

“I takes you!” I barked. “My fifty says you leaves that ring on a shutter. Who holds stakes?”

“Not me,” said Ace, hurriedly.

“Don’t worry,” snapped Black Jack, “I wouldn’t trust a nickel of my dough in your greasy fingers. Not a nickel. Hey Bunger!”

At the yell, in come a bewhiskered old wharf-rat which exuded a strong smell of trader’s rum.

“What you want?” he said. “Buy me a drink, Black Jack.”

“I’ll buy you a raft of drinks later,” growled O’Brien. “Here, hold these stakes, and if you let a dip get ’em, I’ll pull out all your whiskers by the roots.”

“They won’t get it offa me,” promised old Bunger. “I know the game, you bet.”

Which he did, having been a dip hisself in his youth; but he had one virtue—when he was sober, he was as honest as the day is long with them he considered his friends. So he took the two fifties, and me and O’Brien, after a few more mutual insults, slung on our bathrobes and strode up the aisle, to the applause of the multitude, which cheered a long-looked-for melee.

The Sea Girl wasn’t in port—in fact, I’d come to Singapore to meet her, as she was due in a few days. So, as they was none of my crew to second me, Ace had provided a couple of dumb clucks.

He’d also give Black Jack a pair of saps, as O’Brien’s ship, the Watersnake, wasn’t in port either.

The gong whanged, the crowd roared, and the dance commenced. We was even matched. We was both as tough as nails, and aggressive. What we lacked in boxing skill, we made up for by sheer ferocity. The Arena never seen a more furious display of hurricane battling and pile-driving punching; it left the crowd as limp as a rag and yammering gibberish.

At the tap of each gong we just rushed at each other and started slugging. We traded punches ’til everything was red and hazy. We stood head to head and battered away, then we leaned on each other’s chest and kept hammering, and then we kept our feet by each resting his chin on the other’s shoulder, and driving away with short-arm jolts to the body. We slugged ’til we was both blind and deaf and dizzy, and kept on battering away, gasping and drooling curses and weeping with sheer fighting madness.

At the end of each round our handlers would pull us apart and guide us to our corners, where they wouldst sponge off the blood and sweat and tears, and douse us with ice-water, and give us sniffs of ammonia, whilst the crowd watched, breathless, afeared neither of us would be able to come up for the next round. But with the marvelous recuperating ability of the natural-born slugger, we would both revive under the treatments, and stiffen on our stool, glaring red-eyed at each other, and, with the tap of the gong, it would begin all over again. Boy, that was a scrap, I’m here to tell you!

Time and again either him or me would be staggering on the ragged edge of a knockout, but would suddenly rally in a ferocious burst of battling which had the crowd delirious. In the eighth he put me on the canvas with a left hook that nearly tore my head off, and the crowd riz, screaming. But at “eight” I come up, reeling, and dropped him with a right hook under the heart that nearly cracked his ribs. He lurched up just before the fatal “ten,” and the gong sounded.

The end of the ninth found us both on the canvas, but ten rounds was just too short a time for either of us to weaken sufficient for a knockout. But I believe, if it had gone five more rounds, half the crowd would of dropped dead. The finish found most of ’em feebly flapping their hands and croaking like frogs. At the final gong we was standing head to head in the middle of the ring, trading smashes you couldst hear all over the house, and the referee pulled us apart by main strength and lifted both our hands as an indication that the fight was a draw.

Drawing on his bathrobe, Black Jack come over to my corner, spitting out blood and the fragments of a tooth, and he said, grinning like a hyena, “Well, you owe me fifty bucks which you bet on lickin’ me.”

“And, by the same token, you owe me fifty,” I retorted. “Your bet was you’d flatten me. By golly, I don’t know when I ever enjoyed a scrap more! I don’t see how Bad Bill licked you.”

O’Brien’s face darkened like a thunder-cloud.

“Don’t mention that egg to me,” he snapped. “I can’t figger it out myself. You hit me tonight a lot harder’n he ever did. I’d just battered him clean across the ring, and he was reelin’ and rockin’—then it happened. All I know is that he fell into me, and we in a sort of half-clinch—then bing! The next thing I knowed, they was pourin’ water on me in my dressin’-room. They said he socked me on the jaw as we broke, but I never seen the punch—or felt it.”

“Well,” I said, “forget it. Let’s get our dough from old Bunger and go get a drink. Then I gotta go back to my room.”

“What you turnin’ in so soon for?” he scowled. “The night’s young. Let’s see if we can’t shake up some fun. They’s a couple of tough bouncers down at Yota Lao’s I been layin’ off to lick a long time—”

“Naw,” I said, “I got business at the Deluxe. But we’ll have a drink, first.”

So we looked around for Bunger, and he wasn’t nowhere to be seen. We went back to our dressing-rooms, and he wasn’t there either.

“Now, where is the old mutt?” inquired Black Jack, fretfully. “Here’s us famishin’ with thirst, and that old wharf-rat—”

“If you mean old Bunger,” said a lounger, “I seen him scoot along about the fifth round.”

“Say,” I said, as a sudden suspicion struck me, “was he drunk?”

“If he was, I couldn’t tell it,” said Black Jack.

“Well,” I said, “I thought he smelt of licker.”

“He always smells of licker,” answered O’Brien, impatiently. “I defies any man to always know whether the old soak’s drunk or sober. He don’t ack no different when he’s full, except you can’t trust him with dough.”

“Well,” I growled, “he’s gone, and likely he’s blowed in all our money already. Come on; let’s go hunt for him.”

So we donned our street clothes, and went forth. Our mutual battering hadn’t affected our remarkable vitalities none, though we both had black eyes and plenteous cuts and bruises. We went down the street and glanced in the dives, but we didn’t see Bunger, and purty soon we was in the vicinity of the Deluxe.

“Come on up to my room,” I said. “I got fifty bucks there. We’ll get it and buy us a drink. And listen, Johnny Kyelan’s up there, but you keep your trap shut about it, see?”

“Okay,” he said. “If Johnny’s in a jam, I ain’t the man to blab on him. He ain’t got no sense, but he’s a good kid.”

So we went up to my room; everybody in the house was either asleep or had gone out some place. I knocked cautious, and said, “Open up, kid; it’s me, Costigan.”

They wasn’t no reply. I rattled the knob impatiently and discovered the door wasn’t locked. I flang it open, expecting to find anything. The room was dark, and, I switched on the light. Johnny wasn’t nowhere to be seen. The room wasn’t mussed up nor nothing, and though Mike kept growling deep down in his throat, I couldn’t find a sign of anything suspicious. All I found was a note on the table. I picked it up and read, “Thanks for the fifty, sucker! Johnny.”

“Well, of all the dirty deals!” I snarled. “I took him in and perteckted him, and he does me outa my wad!”

“Lemme see that note,” said Black Jack, and read it and shook his head. “I don’t believe this here’s Johnny’s writin’,” he said.

“Sure it is,” I snorted, because I was hurt deep. “It’s bad to lose your dough; but it’s a sight worse to find out that somebody you thought was your friend is nothing but a cheap crook. I ain’t never seen any of his writin’ before, but who else would of writ it? Nobody but him knowed about my wad. Black Mandarins my eye!”

“Huh?” Black Jack looked up quick, his eyes glittering; that phrase brung interest to anybody in Singapore. So I told him all about what Johnny had told me, adding disgustedly, “I reckon I been took for a sucker again. I bet the little rat had got into a jam with the cops, and he just seen a chance to do me out of my wad. He’s skipped; if anybody’d got him, the door would be busted, and somebody in the house would of heered it. Anyway, the note wouldn’t of been here. Dawggonit, I never thought Johnny was that kind.”

“Me neither,” said Black Jack, shaking his head, “and you don’t figger he ever saw them Black Mandarins.”

“I don’t figger they is any Black Mandarins,” I snorted, fretfully.

“That’s where you’re wrong,” said O’Brien. “Plenty of people has seen ’em—and others saw ’em and didn’t live to tell who they was. I said all the time it was more’n any one man which was doin’ all these crimes. I thought it was a gang—”

“Aw, ferget it,” I said. “Come on. Johnny’s stole my wad, and old Bunger has gypped the both of us. I’m a man of action. I’m goin’ to find the old buzzard if I have to take Singapore apart.”

“I’m with you,” said Black Jack, so we went out into the street and started hunting old Bunger, and, after about a hour of snooping into low-class dives, we got wind of him.

“Bunger?” said a bartender, twisting his flowing black mustaches. “Yeah, he was here earlier in the evenin’. He had a drink and said he was goin’ to Kerney’s Temple of Chance. He said he felt lucky.”

“Lucky?” gnashed Black Jack. “He’ll feel sore when I get through kickin’ his britches up around his neck. Come on, Steve. I oughta thought about that before. When he’s lit, he always thinks he can beat that roulette wheel at Kerney’s.”

So we went into the mazes of the waterfront till we come to Kerney’s Temple, which was as little like a temple as a critter couldst imagine. It was kinda underground, and, to get to it, you went down a flight of steps from the street.

We went in, and seen a number of tough-looking eggs playing the various games or drinking at the bar. I seen Smoky Rourke, Wolf McGernan, Red Elkins, Shifty Brelen, John Lynch, and I don’t know how many more—all shady characters. But the hardest looking one of ’em was Bad Bill hisself—one of these square-set, cold-eyed thugs which sports flashy clothes, like a gorilla in glad rags. He had a thin, sneering gash of a mouth, and his big, square, hairy hands glittered with diamonds. At the sight of his enemy, Black Jack growled deep in his throat and quivered with rage.

Then we seen old Bunger, leaning disconsolately against the bar, watching the clicking roulette wheel. Toward him we strode with a beller of rage, and he started to run, but seen he couldn’t get away.

“You old mud-turtle!” yelled Black Jack. “Where’s our dough?”

“Boys,” quavered old Bunger, lifting a trembling hand, “don’t jedge me too harsh! I ain’t spent a cent of that jack.”

“All right,” said Black Jack, with a sigh of relief. “Give it to us.”

“I can’t,” he sniffled, beginning to cry. “I lost it all on this here roulette wheel!”

“What!” our maddened beller made the lights flicker.

“It was this way, boys,” he whimpered. “Whilst I was watchin’ you boys fight, I seen a dime somebody’d dropped on the floor, and I grabbed it. And I thought I’d just slip out and get me a drink and be back before the scrap was over. Well, I got me the drink, and that was a mistake. I’d already had a few, and this’n kinda tipped me over the line. When I got some licker in me, I always get the gamblin’ craze. Tonight I felt onusual lucky, and I got the idea in my head that I’d beat it down to Kerney’s, double or triple this roll, and be that much ahead. You boys would get back your dough, and I’d be in the money, too. It looked like a great idea, then. And I was lucky for a while, if I’d just knowed when to quit. Once I was a hundred and forty-five dollars ahead, but the tide turned, and, before I knowed it, I was cleaned.”

“Dash-blank-the-blank-dash!” said Black Jack, appropriately. “This here’s a sweet lay! I oughta kick you in the pants, you white-whiskered old mutt!”

“Aw,” I said, “I wouldn’t care, only that was all the dough I had, except my lucky half-dollar.”

“That’s me,” snarled O’Brien. “Only I ain’t got no half-dollar.”

About this time up barged Bad Bill.

“What’s up, boys?” he said, with a wink at the loafers.

“You know what’s up, you louse!” snarled Black Jack. “This old fool has just lost a hundred bucks on your crooked roulette game.”

“Well,” sneered Bad Bill, “that ain’t no skin offa your nose, is it?”

“That was our money,” howled Black Jack. “And you gotta give it back!”

Kerney laughed in his face. He took out a roll of bills and fluttered the edges with his thumb.

“Here’s the dough he lost,” said Kerney. “Mebbe it was yours, but it’s mine now. What I wins, I keeps—onless somebody’s man enough to take it away from me, and I ain’t never met anybody which was. And what you goin’ to do about it?”

Black Jack was so mad he just strangled, and his eyes stood out. I said, losing my temper, “I’ll tell you what we’re goin’ to do, Kerney, since you wanta be tough. I’m goin’ to knock you stiff and take that wad offa your senseless carcass.”

“You are, hey?” he roared, blood-thirstily. “Lemme see you try it, you black-headed sea-rat! Wanta fight, eh? All right. Lemme see how much man you are. Here’s the wad. If you can lick me, you can have it back. I won it fair and square, but I’m a sport. You come around here cryin’ for your money back—all right, we’ll see if you’re men enough to fight for it!”

I growled deep and low, and lunged, but Black Jack grabbed me.

“Wait a minute,” he yelped. “Half that dough’s mine. I got just as much right to sock this polecat as you has, and you know it.”

“Heh! Heh!” sneered Kerney, jerking off his coat and shirt. “Settle it between yourselves. If either one of you can lick me, the dough’s yours. Ain’t that fair, boys?”

All the assembled thugs applauded profanely. I seen at a glance they was all his men—except old Bunger, which didn’t count either way.

“It’s my right to fight this guy,” argued Black Jack.

“We’ll flip a coin,” I decided, bringing out my lucky half-dollar. “I’ll take—”

“I’ll take heads,” busted in Black Jack, impatiently.

“I said it first,” I replied annoyedly.

“I didn’t hear you,” he said.

“Well, I did,” I answered pettishly. “You’ll take tails.”

“All right, I’ll take tails,” he snorted in disgust. “Gwan and flip.”

So I flopped, and it fell heads.

“Didn’t I say it was my lucky piece?” I crowed jubilantly, putting the coin back in my pocket and tearing off my shirt, whilst Black Jack ground his teeth and cussed his luck something terrible.

“Before I knock your brains out,” said Kerney, “you got to dispose of that bench-legged cannibal.”

“If you mean Mike, you foul-mouthed skunk,” I said, “Black Jack can hold him.”

“And let go of him so he can tear my throat out just as I got you licked,” sneered Kerney. “No, you don’t. Take this piece of rope and tie him up, or the scrap’s off.”

So, with a few scathing remarks which apparently got under even Bad Bill’s thick hide, to judge from his profanity, I tied one end of the rope to Mike’s collar and the other’n to the leg of a heavy gambling table. Meanwhile, the onlookers had cleared away a space between the table and the back wall, which was covered by a matting of woven grass. To all appearances, the back wall was solid, but I thought they must be a lot of rats burrowing in there, because every now and then I heered a kind of noise like something moving and thumping around.

Well, me and Kerney approached each other in the gleam of the gas-lights. He was a big, black-browed brute, with black hair matted on his barrel chest and on his wrists, and his hands was like sledge-hammers. He was about my height, but heavier.

I started the scrap like I always do, with a rush, slugging away with both hands. He met me, nothing loath. The crowd formed a half-circle in front of the stacked-up tables and chairs, and the back wall was behind us. Above the thud and crunch of blows I couldst hear Mike growling as he strained at his rope, and Black Jack yelling for me to kill Kerney.

Well, he was tough and he could hit like a mule kicking. But he was fighting Steve Costigan. There, under the gas-lights, with the mob yelling, and my bare fists crunching on flesh and bone, I was plumb in my element. I laughed at Bad Bill as I took the best he could hand out, and come plunging in for more.

I worked for his belly, repeatedly sinking both hands to the wrists, and he began to puff and gasp and go away from me. My head was singing from his thundering socks, and the taste of blood was in my mouth, but that’s a old, old story to me. I caught him on the ear and blood spattered. Like a flash, up come his heavy boot for my groin, but I twisted aside and caught him with a terrible right-hander under the heart. He groaned and staggered, and a ripping left hook to the body sent him down, but he grabbed my belt as he fell and dragged me with him.

On the floor he locked his gorilla arms around me, and spat in my eye, trying to pull my head down where he could sink his fangs in my ear. But my neck was like iron, and I pulled back, fighting mad, and, getting a hand free, smashed it savagely three times into his face. With a groan, he went slack. And just then a heavy boot crashed into my back, purty near paralyzing me, and knocking me clear of Kerney.

It was John Lynch which had kicked me, and even as I snarled up at him, trying to get up, I heered Black Jack roar, and I heered the crash of his iron fist under Lynch’s jaw, and the dirty yegg dropped amongst the stacked-up tables and lay like a empty sack.

The thugs surged forward with a menacing rumble, but Black Jack turned on ’em like a maddened tiger, his teeth gleaming in a snarl, his eyes blazing, and they hesitated. And then I climbed on my feet, the effecks of that foul lick passing. Kerney was slavering and cursing and trying to get up, and I grabbed him by his hair and dragged him up.

“Stand on your two feet and fight like as if you was a man,” I snarled disgustedly, and he lunged at me sudden and unexpected, trying to knee me in the groin. He fell into me, and, as I pulled out of a half-clinch, I heered Black Jack yell suddenly, “Look out, Steve! That’s the way he got me!”

And simultaneous I felt Kerney’s hand at the side of my neck. Instinctively, I jerked back, and as I did, Kerney’s thumb pressed cunning and savage into my neck just below the ear. Jiu-jitsu! Mighty few white men know that trick—the Japanese death-touch, they call it. If I hadn’t been going away from it, so he didn’t hit the exact nerve he was looking for, I’d of been temporarily paralyzed. As it was, my heavy neck muscles saved me, though for a flashing instant I staggered, as a wave of blindness and agony went all over me.

Kerney yelled like a wild beast, and come for me, but I straightened and met him with a left hook that ripped his lip open from the corner of his mouth to his chin, and sent him reeling backward. And, clean maddened by the dirty trick he had tried on me, I throwed every ounce of my beef into a thundering right swing that tagged him square on the jaw.

It was just a longshoreman’s haymaker with my whole frame behind it, and it lifted him clean offa his feet and catapulted him bodily against the back wall. Crash! The matting tore, the wood behind it splintered, and Kerney’s senseless form smashed right on through!

The force of my swing throwed me headlong after Kerney, and I landed with my head and forearms through the hole he’d made. The back wall wasn’t solid! They was a secret room beyond it. I seen Kerney lying in that room with his feet projecting through the busted partition, and beyond I seen another figger—bound and gagged and lying on the floor.

“Johnny!” I yelled, scrambling up, and behind me rose a deep, ominous roar. Black Jack yelled, “Look out, Steve!” and a bottle whizzed past my ear and crashed against the wall. Simultaneous come the thud of a sock and the fall of a body, as Black Jack went into action, and I wheeled as Kerney’s thugs come surging in on me.

Black Jack was slugging right and left, and men were toppling like ten-pins, but they was a whole room full of ’em. I saw old Bunger scooting for the exit, and I heered Mike roaring, lunging against his rope. I caught the first thug with a smash that near broke his neck, and then they swarmed all over me, and I cracked Red Elkins’ ribs with my knee as we went to the floor.

I heered Black Jack roaring and battling, and I shook off my attackers and riz, fracturing Shifty Brelen’s skull, and me and Black Jack stiffened them deluded mutts till we was treading on a carpet of senseless yeggs, but still they come, with bottles and knives and chair-legs, till we was both streaming blood.

Black Jack hadst just been felled with a table-leg, and half a dozen of ’em was stomping on my prostrate form, whilst I was engaged in gouging and strangling three or four I had under me, when Mike’s rope broke under repeated gnawings and lunges. I heered him beller, and I heered a yegg yip as Mike’s iron fangs met in his meat. The clump on me bust apart, and I lurched up, roaring like a bull and shaking the blood in a shower from my head.

Black Jack come up with the table-leg he’d been floored with, and he hit Smoky Rourke so hard they had to use a pulmotor to bring Smoky to. The battered mob staggered dizzily back, and scattered as Mike plunged and raged amongst them.

Spang! Wolf McGernan had broke away from the melee and was risking killing some of his mates to bring us down. They run for cover, screeching. Black Jack throwed the table-leg, but missed, and the three of us—him and Mike and me—rushed McGernan simultaneous.

His muzzle wavered from one to the other as he tried to decide quick which to shoot, and then crack! Wolf yelped and dropped his gun; he staggered back against the wall, grabbing his wrist, from which blood was spurting.

The yeggs stopped short in their head-long fight for the exit, and me and Black Jack wheeled. A dozen policemen was on the stairs with drawed guns and one of them guns was smoking.

The thugs backed against the wall, their hands up, and I run into the secret room and untied Johnny Kyelan.

All he could say was, “Glug ug glug!” for a minute, being nearly choked with fear and excitement and the gag. But I hammered him on the back, and he said, “They got me, Steve. They sneaked into the hall and knocked on the door. When I stooped to look through the key-hole, as they figgered I’d do—its a natural move—they blew some stuff in my face that knocked me clean out for a few minutes. While I was lying helpless, they unlocked the door with a skeleton key and came in. I was coming to myself, then, but they had guns on me and I didn’t dare yell for help.

“They searched me, and I begged them to leave your fifty dollars on the table because I knew it was all the money you had, but they took it, and wrote a note to make it look like I’d skipped out with the money. Then they blew some more powder in my face, and the next thing I knew I was in a car, being carried here.

“They were going to finish me before daylight. I heard the Chief Mandarin say so.”

“And who’s he?” we demanded.

“I don’t mind telling you now,” said Johnny, looking at the yeggs which was being watched by the cops, and at Bad Bill, who was just beginning to come to on the floor. “The Chief of the Mandarins is Bad Bill Kerney! He was a racketeer in the States, and he’s been working the same here.”

An officer broke in: “You mean this man is the infamous Black Mandarin?”

“You’re darn tootin’,” said Johnny, “and I can prove it in the courts.”

Well, them cops pounced on the dizzy Kerney like gulls on a fish, and in no time him and his gang, such as was conscious, was decorated with steel bracelets. Kerney didn’t say nothing, but he looked black murder at all of us.

“Hey, wait!” said Black Jack, as the cops started leading them out. “Kerney’s got some dough which belongs to us.”

So the cop took a wad offa him big enough to choke a shark, and Black Jack counted off a hundred and fifty bucks and give the rest back. The cops led the yeggs out, and I felt somebody tugging at my arm. It was old Bunger.

“Well, boys,” he quavered, “don’t you think I’ve squared things? As soon as the roughhouse started, I run up into the street screamin’ and yellin’ till all the cops within hearin’ come on the run!”

“You’ve done yourself proud, Bunger,” I said. “Here’s a ten spot for you.”

“And here’s another’n,” said Black Jack, and old Bunger grinned all over.

“Thank you, boys,” he said, ruffling the bills in his eagerness. “I gotta go now—they’s a roulette wheel down at Spike’s I got a hunch I can beat.”

“Let’s all get outa here,” I grunted, and we emerged into the street and gazed at the street-lamps, yellow and smoky in the growing daylight.

“Boy, oh, boy!” said Johnny. “I’ve had enough of this life. It’s me for the old U.S.A. just as soon as I can get there.”

“And a good thing,” I said gruffly, because I was so glad to know the boy wasn’t a thief and a cheat that I felt kinda foolish. “Snappy kids like you got no business away from home.”

“Well,” said Black Jack, “let’s go get that drink.”

“Aw, heck,” I said, disgustedly, as I shoved my money back in my pants, “I lost my good-luck half-dollar in the melee.”

“Maybe this is it,” said Johnny, holding it out. “I picked it up off the floor as we were coming out.”

“Gimme it,” I said, hurriedly, but Black Jack grabbed it with a startled oath.

“Good luck piece?” he yelled. “Now I see why you was so insistent on takin’ heads. This here blame half-dollar is a trick coin, and it’s got heads on both sides! Why, I hadn’t a chance. Steve Costigan, you did me out of a fight, and I resents it! You got to fight me.”

“All right,” I said. “We’ll fight again tonight at Ace’s Arena. And now let’s go get that drink.”

“Good heavens,” said Johnny, “It’s nearly sun-up. If you fellows are going to fight again tonight, hadn’t you better get some rest? And some of those cuts you both got need bandaging.”

“He’s right, Steve,” said Black Jack. “We’ll have a drink and then we’ll get sewed up, and then we’ll eat breakfast, and after that we’ll shoot some pool.”

“Sure,” I said, “that’s a easy, restful game, and we oughta take things easy so we can be in shape for the fight tonight. After we shoot some pool, we’ll go to Yota Lao’s and lick some bouncers you was talkin’ about.”