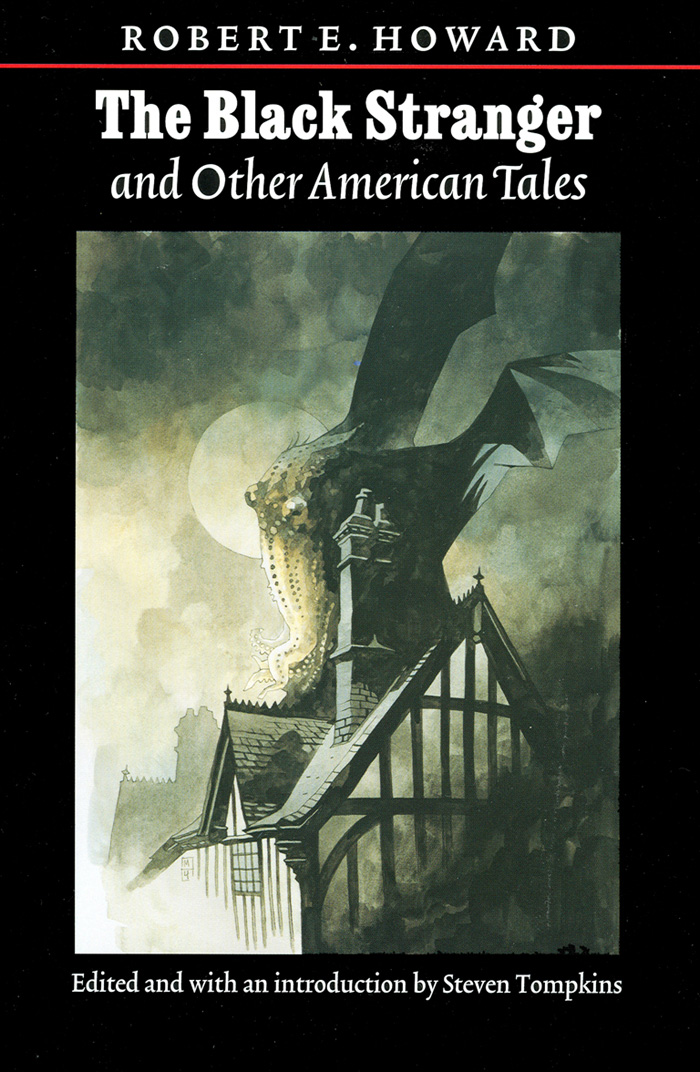

Cover from the collection The Black Stranger and Other American Tales (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in Swords Against Darkness, 1977, as a composite draft completed by Andrew J. Offutt,

though this is Howard’s typescript, taken from the 2005 collection The Black Stranger and Other American Tales.

And what I am sure of is that there is not any gold nor any other metal in all that country.

—Coronado

The snap of a bowstring, the shrill scream of a horse death-stricken broke the stillness. The Spanish barb reared, the feathered end of the arrow quivering behind its foreleg, and went down in a headlong plunge. The rider sprang free as it fell, and hit on his feet with a dry clang of steel. He staggered, empty hands flung wide, fighting to regain his balance. His matchlock had fallen several feet away and the match had gone out. He drew his broadsword and looked about him, trying to locate the beady black eyes he knew glittered at him from somewhere in the close-set greasewood bushes that edged the rim of the dry wash to his left. Even as he sought the slayer of his steed, the man appeared, rising upright and springing over a low shrub almost with one movement. A vengeful yell of triumph quivered in the late afternoon stillness. An instant they faced one another, with a fifty foot stretch of tawny sand between—the New World and the Old personified in them.

About them, from horizon to horizon, the naked plains swept away and away to mingle in the faint ocean-like haze that hovered along the turquoise rim of the sky. No bird cried, no beast moved. The dead horse lay motionless. In all that vast expanse those two were the only living, sentient beings—the tall, grey-bearded man in tarnished steel; the wiry, copper-skinned brave, naked in his beaded loin-clout, with his black eyes burning redly under the square-cut bang of his black mane.

Those black eyes flickered toward the matchlock, lying out of reach and useless, and the red glints grew more lurid. The Apache had learned the deadliness of the white man’s guns. But now he felt that the advantage was with him. His left hand gripped a short, stout bow of bois d’arc, backed with sinew; in his right was a flint-headed dogwood arrow. He did not reach for the stone-headed hatchet at his girdle. He had no intention of coming within the sweep of that long sword which glimmered dully in the rays of the westering sun. For an instant the tableau held motionless, as he swept his fierce gaze over his enemy. He knew his flint darts would splinter on the white man’s armor; but no vizor covered the bearded face. Yet he was unwilling to waste a single arrowhead, which represented hours of tedious toil. Cat-like he glided toward his prey, not in a straight line, but springing from side to side, to confuse the other, to make him shift his position and so to catch him at the end of a motion, where he could not dodge the winged death that leaped at him. The Apache did not fear a sudden sword-swinging rush. The steel-clad man could never match his own naked fleetness of foot. He had the white man at his mercy and could kill in his own way, without risk. With a short fierce cry he stopped short, whipped up the bow and jerked back the arrow—just as the white man plucked a pistol from his belt and fired point-blank.

The arrow whined erratically skyward. The bow slipped from the warrior’s hands as the Apache went to his knees, choking, blood gushing between the fingers that clutched at his muscular breast. He sank down in the sand, his bloodshot, glazing eyes fixed in a last spasm of despairing hate on his slayer. The white man always had something in reserve, something unguessed. The warrior saw the armored man looming above him like a grim god, implacable and unconquerable, with bleak, pitiless eyes. In that gleaming figure he read the ultimate doom of his whole race. Weakly, as a dying snake hisses, he reared his head, spat at his slayer and slid back dead.

Hernando de Guzmán sheathed his sword, reloaded the clumsy wheel-lock pistol and replaced it beside its mate, reflecting briefly that it was well for him that this particular Apache had not been familiar with the shorter arms. He sighed as he looked down at his dead horse. Like many of his race he had a fondness for fine horses and displayed toward them a kindliness seldom if ever showed to human beings. He made no move to secure the ornately decorated saddle and bridle. In the miles he must cover afoot he would find exhaustion enough without further burdening himself. The matchlock he secured, and with it resting on his shoulder he stood motionless for a moment, seeking to orient himself.

A feeling that he was already lost tugged at him—had been tugging at him for the last hour, even before his horse was killed. Veteran though he was, he had wandered further afield than was wise, in vain pursuit of an antelope, whose flaring white scud, gleaming in the sunlight, had led him like a will-o’-the-wisp over sand hills and prairie. He had tried to keep the location of the camp in his mind, but he feared that he had failed. There were no landmarks in these plains that swept without a break from sunrise to sunset. An expedition, driving its own sustenance on the hoof, was like a ship groping its way across an unknown sea, its only chance of survival lying in its self-sufficiency. A lone rider was like a man adrift in an open boat, without food or water or compass. A man afoot was a man as good as dead, unless he could reach his companions swiftly.

De Guzmán briefly explored the shallow gully in hopes of finding a horse. There was none. The Apaches had not yet taken to horse-riding. Steeds strayed or stolen from the Spaniards were used as food, though he had heard tales of a terrible tribe to the north whose warriors were already horsemen.

The Spaniard chose the direction he believed to be the right one, and took up his march. He lifted his morion and ran his fingers through his damp, greying locks, but the heat of the sun made him replace it. Years of armor-wearing accustomed him to the weight and heat of the steel that cased him. Later it would add to his weariness, but it might stand him in good stead if he met other roaming warriors of the plains. The presence of the lone warrior he had killed proved that there was a whole clan somewhere in the vicinity.

The sun dipped toward the western horizon; across its red eye he moved, a tiny pygmy in the midst of the illimitable plain that mocked him in its grim vastness and silence.

The sun seemed to poise on the desert rim before it rushed from sight. A thin streamer of crimson ran north and south around the skyline. The sky seemed to expand, to deepen with the coming of sunset. Already in the east the hot volcanic blue was paling to the steel of Toledo swords.

De Guzmán stopped and dropped the butt of his matchlock to the earth. It rang on the hard ground and left no print. He looked back the way he had come, unable to trace his own route over the short dry springy grass. He had passed, leaving no footprints. He might have been a phantom, drifting futilely across a sleeping, indifferent land. The plains were impervious to human efforts. Man left no trace upon them; he marched, fought, struggled and died cursing the gods that betrayed him, but the plains dreamed on, with no more trace of his passing than he had left on the surface of the sea.

“Gold!” muttered de Guzmán, and laughed sardonically.

He had come a long way since his horse fell. If he were going in the right direction he would have approached the camp near enough to have heard the shots that the men would be firing to guide him back. He was lost. He knew not in which direction to turn. The plains had claimed him for their own. His bones, bred of the wheat and oil and wine of Old Spain, would bleach on the dreary expanse with the bones of the Apache, the coyote and the rattlesnake. But the thought stirred in him no religious or sentimental horror. Spain was far away, a dream and a memory, a Land of Cockaigne that had been real once, in the golden glow of youth and desire, but now had no more reality than a ghost-continent lost in a sea of mist.

Spanish blood was no more sacred than the blood of other races; blood was only blood, and he had seen oceans of it spilled: Spanish blood, English blood, Huguenot blood, Inca blood, Aztec blood—the royal blood of Montezuma dripping from the parapets of Tenochtitlan—blood running ankle-deep in the plaza of Cajamarca, about the frantic feet of doomed Atahualpa.

But the will to live burned fiercely in his breast, the blind, black instinct toward life, which has no relation to intellect or reason or anything else. As such he recognized and obeyed it. He had no more illusions concerning existence. He knew, as all men know who have bared its core, that the game was not worth the candle. Men rationalize the blind instinct of self preservation, and build glib air-castles explaining why it is better to live than to die, when their boasted—but ignored—intellect is, in every phase, a negation of life. But civilized men hate and fear their instincts, as they hate and fear every heritage from the blind, squalling pit of primordial beginnings that bred them. Dogs, apes, elephants, these creatures obey instincts and live only because instinct bids them live. Man’s urge toward life is no less blind and reasonless, but, abhorring his kinship with those creatures who had the misfortune not to be made in the Deity’s image—having no prophets to declare it—fondles his favorite delusion that he is guided wholly by reason, even when reason tells him it is better to die than to live. It is not the intellect he boasts that bids him live, but the blind, black, unreasoning beast-instinct.

This de Guzmán knew and admitted. He did not try to deceive himself into believing that there was any intellectual reason why he should not give up the agonizing struggle, place the muzzle of a pistol to his head and quit an existence whose savor had long ago become less than its pain. If by some miracle he found his way back to Coronado’s camp, and at last to Mexico or fabled Quivira, there was no reason to believe life would be any less sordid or more desirable than it had been before he marched northward in search of the Seven Cities of Gold. But that blind instinct bade him fight for life to its last gagging gasp, to live in spite of hell or the actions of his fellow men. It burned as strongly now as it had that long-past day in his youth when he fought shoulder to shoulder with Cortez and saw the plumed hordes of Montezuma roll in like a wave to engulf the desperate handful which defied them.

To live! Not for love, nor profit, nor ambition, nor for a cause—all these things were wisps of mist, phantoms conjured up by men to explain the unexplainable. To live, because in his being there was implanted too deeply a blind black urge to live, that was in itself question and answer, desire and goal, beginning and end, and the answer to all the riddles in the universe.

And so the Conquistador laughed sardonically, shouldered his clumsy matchlock and prepared to take up anew his futile march, into ultimate oblivion and silence.

Then he heard the drum.

Even, deliberate, unhurried, its voice rolled across the plains, as mellow as the booming of waves of wine on a golden coast. He posed a moment, an image in steel, straining his ears. It came from the east, he decided, and it was no Apache drum. It was alien, exotic, like a drum he had heard that night when he stood on a flat roof in Cajamarca and watched the myriad fires of the great Inca’s army twinkling through the night, while near by the passionless voice of the Bastard Pizarro spun black webs of treachery and infamy.

He closed his eyes, rubbed a hand across them; opened them, listened, with his head tilted sidewise, wondering if the heat and silence were already melting his brain and giving birth to phantasies. No! It was no mirage framed in sound. Steady as the pulse in his own temple it throbbed and throbbed, touching obscure chords in his brain until his whole being thrummed with the call of mystery. For a moment dead ashes flickered into flame, as if his dead youth were for the moment revived. In that mellow sound were magic and allure. He felt again, for a moment, as he had felt so long ago when he gripped a ship’s rail with hot eager hands and saw the golden fabled coast of Mexico loom out of the morning mist, and felt the lure of adventure and plunder that was like the blast of a golden trumpet ringing down the wind.

It passed, but a pulse in his temple beat swift staccato so that he laughed at himself. And without pausing to argue the matter with himself he turned and strode eastward.

The sun had set; the brief twilight of the plains glowed and faded. The stars blinked out, great, white cold stars, indifferent to the tiny figure plodding across the shadowless vastness. The sparse shrubs crouched like nameless beasts waiting for the wanderer to stumble and fall. The drum pulsed steadily on and on, booming its golden wavelets of sound across the wasteland. It roused memories long faded, alien and exotic, of flaming gardens of great blossoms, steaming jungles, tinkling fountains, and always an undertone of golden drops tinkling on a golden paving.

Gold! Again he was following a quest of gold—the same, old, threadbare quest that had led him around the world over seas, through jungles, and through the smoke and flame of butchered cities. Like Coronado, sleeping somewhere on these plains and wrapped in fantastic dreams, he was following a call of gold, and one as tangible as that which maddened Francisco’s dreams. Coronado, seeking vainly for the cities of Cibolo, with their lofty houses and glittering treasures, where even the slaves ate from golden dishes! De Guzmán smiled bitterly, with his parched, thirst-twisted lips, reflecting that in future years Coronado would become a symbol for the chasing of will-o’-the-wisps. Historians to come, wise with the blatant wisdom of hindsight, would mock at him as a visionary and a fool. His name would become a taunt for treasure-seekers. Yet with what reason? Why should not a Spaniard search for gold in the countries north of the Río Grande? Why refuse to credit the tales of Cibolo? They were no more incredible than the tales of Peru and Mexico had been, less than a generation ago. There was as much reason to believe Cibolo existed as there had been to believe that Peru existed, before the swineherd Pizarro sailed southward. But the world judges by failure or success. Coronado was of the same hardheaded, heavy-handed breed as Pizarro and Cortez. But they found gold and would go down in history as robbers and plunderers; Coronado found no gold and would go down in history as a visionary, a credulous believer in myths, a chaser of non-existent rainbows. De Guzmán laughed, and his laughter was not pleasant, embodying his personal opinion of the human race, which was not flattering.

So through the night he followed the mellow booming of the drum which grew subtly louder as he advanced. In the small hours of morning, when his feet seemed weighted not with steel but with lead, and sleep filled his eyes like dust, so that he kept blinking continually, he was aware of a vague bulk looming among the stars on the eastern horizon, and lights twinkled which might have been stars, but which he believed to be fires. And the drum was not far away now; he caught minor notes and undertones he had not heard before, strange rustlings and murmurings, like the swish of the skirts of dark-eyed Aztec women, or the soft low gurglings of their laughter that tinkled among the silvery fountains in the gardens of Tenochtitlan before the Spanish swords reddened those gardens with blood. Why should a drum speak with such voices in this naked, northern land, bringing the lures and mysteries of the faraway south?

On either hand he made out the faint outlines of a long ridge. He was aware that he had made a slow, gradual descent. He knew that he had entered a broad, shallow valley, probably one marking the course of a sunken river. The ridges drew nearer as he advanced, and increased in height.

Just before dawn he stumbled upon a small stream which ran southeastward as all the streams in this land seemed to run. Willows and cottonwoods and straggling bushes grew thick along it. He drank deeply and lay there near the water’s edge, waiting for dawn. The drum pulsed once more, and ceased. Only a single fire twinkled in the dark bulk before him. Silence lay over the ancient land.

With the first streak of milky light in the east, he saw before him the towers and flat roofs of a walled city.

He had roamed too far and seen too many incredible sights to be greatly surprised at anything he saw, yet he lay there wondering at the sight. The city was built of adobe, like the pueblos they had encountered far to the west, but there the resemblance ceased. The walls were sheathed in an enamel-like glaze, decorated with intricate designs in blue, purple, and crimson. It was not large in extent, but the houses, three or four stories in height, did not resemble the beehive huts of the pueblos. The whole city was dominated by a towering structure that gleamed in the dawn-light, and was somewhat like a teocalla, save that it was topped by a dome. He blinked at that. He had never seen anything like it, in Peru, Yucatan or Mexico. The architecture of the city was baffling, obviously allied to that of the Aztecs, yet curiously unlike, as if Aztec hands had reared what an alien brain had conceived.

The city sat in a broad fan-shaped valley, which narrowed and deepened to the east; or rather the cliffs grew higher, for the valley floor remained level. Here once, thousands, perhaps millions of years ago, a great river had cut its channel in the plain and plunged out of sight, leaving a V-shaped valley, walled on three sides by cliffs which grew tall and steep at the apex. The city faced westward, toward the broad opening of the valley, where the ridges dwindled until they vanished. Any enemy must approach from the west, but there was no barrier to guard the city in that direction, where the dwindling ridges were more than a mile apart. The stream entered the broad mouth and wound past the walls at a few hundred yards distance, until it plunged into a cavern in the cliffs. Beyond the city, to the southeast, it flowed through a checkerboard of irrigated fields in which he recognized corn, grapes, berries, nuts and melons. The soil of these barren plains was fertile; all it lacked was water to produce food in abundance. Here the water was supplied. As he watched a small gate in the southeast wall opened and people came into the fields to work, small brown people, well-formed, the men clad in loin-cloths, the women in short sleeveless tunics which left the left breast bare, and came scarcely below mid-thigh.

As he lay there watching, he heard a rumbling to the west, a sound he knew. He jerked his head about and, peering through the intertwining willows, he saw a cloud of dust rising in the valley mouth. Through the dust appeared a long low black line, which grew swiftly as it advanced. The line became a swiftly rolling mass which was seen to be formed of shaggy dark animals with huge, horned heads. It was a stampede of buffalo, the cattle of the plains. The people in the fields ran for the gate which swung open to receive them. The beasts came on blindly, perhaps a thousand of them. Heads appeared along the walls of the city, and a trumpet blared barbarically. De Guzmán had seen buffalo stampede before, but he did not understand why they should charge so blindly toward the city. On they came, in a black, bellowing wave, until it seemed they would dash themselves against the foot of the walls. But three hundred yards from the walls they split as on an unseen barrier, and broke away to the north and south, some crashing through the willows and splashing madly across the stream. Then de Guzmán saw the reason for their stampede.

Their dividing unmasked three hundred Apaches, painted for war, with bows in their hands. They had driven the buffalo before them and running behind and among them, fleet-footed and untiring as wolves, had used the rushing herd as a cover to come within bow-shot of the city.

Now with wild yells they rushed for the gate, showing a recklessness de Guzmán did not associate with the Apaches. He believed they had been drugged with tizwin. No arrows came from the wall, but a strange misty cloud rolled over the wall and floated toward the Apaches. It enveloped them, and their yells ceased. No brave rushed out of the cloud. A stark silence reigned. Then the cloud dispersed and he saw them again—lying where they had fallen, their naked brown bodies gleaming in the rising sun, their feathers stirring in the faint wind.

De Guzmán’s flesh crawled. This was necromancy! Men were coming from the gate, now; tall, sinewy men, clad in plumed helmets and beaded loin-clouts. And de Guzmán felt the old blood-stir of the Conquistador, for those helmets gleamed in the sun as only pure gold can gleam.

The warriors fastened ropes to the ankles of the fallen braves and dragged them inside the gates. The gates were closed and again the workers came into the fields. De Guzmán lay undecided among the willows.

He had satisfied his thirst, but he was ravenously hungry. Yet he hesitated to show himself to these people, who had showed themselves possessed of what was undoubtedly a gift of the Devil. De Guzmán doubted the existence of a Lord of Evil, but he recognized diabolatry nevertheless.

He lay there, and despite himself, he slept. He awoke with a start. A girl had parted the willows and was staring down at him. She was clad in the scanty cotton tunic of the workers in the field, but she did not seem the sort of woman who would have been wearing such a garment. Silks and jewels would have seemed more appropriate. There was an Aztec look about her, but a subtle difference. She was tall, slender but voluptuously formed, and the careless abandon with which she wore her scanty garment left few of her generous contours wholly concealed. De Guzmán felt a quickening of the pulse as he had when he saw the gold of the strange city. His greying beard was no indication of the fire that still burned in the Conquistador’s veins. She was like the strange, exotic women who had intoxicated him in his youth when he first followed the iron captains in hot, unknown lands.

She spoke, stammering in her surprise: “Who are you?”

She had spoken in Aztec, scarcely familiar with its alien enunciations.

He was on his feet in a flash, armor and all, and grasped her wrist as she recoiled. She did not struggle, feeling the iron in his grip. She stared up at him, amazement mirrored more than fear in her wide dark eyes. A subtle perfume filled his nostrils and his head reeled momentarily.

“What does a woman like you at work in the fields?” he muttered.

She ignored his question. “I know what manner of man you are! You are a Spaniard! One of those who slew Montezuma and destroyed his kingdom! You ride beasts called horses, and make thunder and the red flame of death flash out of a metal war-club!”

Eagerly she ran her fingers over his dented breastplate. The touch of her soft warm fingers against his beard sent tingles of pleasure through his iron frame. He smiled to himself, sardonically. What new thing could there be for him to learn about women, who could not even remember how many he had held in his arms during his wild career? But his instincts drew him to her, and he did not resist or question them.

“Word came to the North,” she said. “Word of the slaughter made in Mexico—I was but a baby then. Men doubted—but no more tribute came from Montezuma—”

“Tribute?” The word was startled out of him. “Tribute? From Montezuma, the emperor of all Mexico?”

“Aye. He and his fathers paid tribute to Nekht Semerkeht for a thousand years—slaves, gold, pelts.”

“Nekht Semerkeht!” It had a strange, alien ring. It was not Aztec, that was certain. Where had he heard it? Dimly, its echo reverberated in the shadowy recesses back of his mind. It seemed somehow associated with a deafening noise, the reek of gunpowder and the reek of spilt blood.

“I have seen men like you!” she said. “Once, when I was ten, I wandered outside the city, and the Apaches caught me and sold me to the Lipans, who sold me to the Karankawas who dwell on the coast far to the south, and are cannibals. Once a great war-canoe with wings came sailing by the coast, and the Karankawa braves went out in their dug-outs and shot their arrows at it. There were men in steel on the deck, like you. They turned great war-clubs of metal toward the canoes and blew them out of the water. I ran away in the confusion and came to a camp of the Tonkewas, who brought me home again for the Tonkewas are our servants. What is your name?”

He told her; she turned it about her tongue, lisping it in her attempts to pronounce it.

“And who are you?” he demanded. He had never released her wrist and now his steel-clad arm slipped about her supple waist. She started at the contact and tried to draw away.

“I am a princess,” she answered haughtily.

“Then what are you doing in a slave’s garment?” he demanded, taking hold of the garment and raising it—possibly to call her attention to it.

Her fine dark eyes filled suddenly with tears and she drooped her head in a sort of wrathful humility.

“I forgot. I am a slave. A toiler in the fields, bearing the weals of the overseer’s whip!”

In angry scorn at herself, she turned lithely and exhibited them to him.

“I, the daughter of kings, whipped like a common slave!”

She spoke rapidly: “Listen, I am Nezahualca, daughter of a line of kings. Nekht Semerkeht reigns in Tlasceltec, but beneath him is a governor, the tlacatecatl, Lord of the Fighting Men. Atzcaputzalco was governor; my lover, Acamapichtli, was an officer under him. I desired that my lover become governor. We intrigued—I have—had—power in the city. But Nekht did not desire it. My lover was fed to the feeders from the sky. I was degraded to the status of a public slave—one of the Totonacs whom my ancestors brought with them centuries ago when they came northward.”

“When was that?” he asked.

“Long ago, when Nekht Semerkeht first came to Tenochtitlan. He reigned there for a space, then he gathered many people and came northward, to found this city. He took only young men and women, newly married.”

De Guzmán suddenly remembered where he had heard that name Nekht Semerkeht—a cry from the bloody lips of an Aztec priest falling in the darkness of the terrible battle on the noche triste, as men, in their last extremity invoke a devil instead of a god.

He remembered, too, vague tales of a city far to the North—from which, he believed grew the tales of Cibolo. He had thought it a legend; but here was the reality.

“Who is Nekht Semerkeht?” he asked. The name was not Aztec.

She gestured vaguely eastward. “He came across the blue ocean, long ago. He is a mighty magician, mightier than the priests of the Toltecs. He came alone and made himself ruler of Mexico. But he grew weary and came north—listen to me, iron man!

“Nekht Semerkeht does not know of your race. Even his magic can not prevail against the thunder of your war-club. Help me to kill him! There are warriors who will follow me, in spite of all. I will gather them in a chamber of his temple. Tonight I will open a gate to you, will lead you into the temple. The overseer who guards the slaves at night, he is a young man who has fallen in love with me. He will do anything I ask. Will you aid me?”

He nodded. “But bring me food.”

“I will bring food and leave it among the bushes. But I must return to the gardens now, before I am missed.”

So all day he lay hidden among the willows, and at night he rose and moved like a steel-clad phantom, dim in the starlight, across the silent gardens until he came to the door she had mentioned. It was opened and she appeared, limned in the faint glow of a tiny hand-cresset, in her scanty garment. With her was a young man in the garments of an overseer.

She caught his steel-gloved hand in her slim fingers.

“Come! The warriors await!”

She led him through narrow streets and shadowy courtyards to a small door in the great temple. Along a dark corridor they moved until they came into a chamber, where ten men waited. Nezahualca cried out sharply. The ten men sat each in his ebon chair, in rigid, unseeing attitudes.

The light went out. Nezahualca screamed in the dark. The young overseer gasped. De Guzmán’s matchlock was wrenched from his hands. He drew his sword and stood tense and listening in the silence which followed. Then a soft hand touched his. He almost struck with his sword before he recognized the feel of a woman’s slim hand. The fingers closed supplely about his, and tugged gently. He followed, gliding as silently as he could in his armor. He was led through a door, along a darkened corridor, on and on. Suddenly, somewhere, a woman screamed, in the voice of Nezahualca.

Smitten by a grisly thought, he ran his fingers along the wrist of the hand that held his. They encountered a few inches of soft smooth wrist, then a hairy, wiry arm! A peal of demoniac laughter burst out in the darkness. Gagging with horror he heaved up his sword and smote blindly, and the horrible guffaw broke in an agonized gurgle.

Something thrashed and flopped in the darkness at his feet, and he turned back, his flesh crawling. That nameless monstrosity with the soft hands of a woman was not leading him anywhere he should go. He turned aside, found a door, and presently, moving at random along another corridor, saw a faint gleam of light far ahead of him.

He was looking down into a chamber, from a sort of balcony. He could see a throne of black ebony, with a back and canopy which hid the occupant, but he knew someone or something sat there. He saw the young overseer and Nezahualca. Stark naked, he hung suspended from a golden chain by his ankles from the ceiling, over a gold brazier which sent up clouds of purple smoke which from time to time hid him completely as high as his waist. He made no sound, but writhed weakly.

Nezahualca, as naked as the youth, lay on a gold, gem-crusted altar directly beneath a circular opening in the dome which showed a disk of blue-black star-clustered night-sky. Her lovely eyes were dilated with fear, her wrists and ankles confined by slender golden chains. She stared wildly up through the roof.

A voice was speaking from the throne, calm, passionless, and merciless: “You were a fool to place trust in a barbarian with a thunder-club. Its necromancy is less than mine. He lost his thunder-club and a child of darkness led him to his doom among the rattlesnakes. And your flesh shall glut the feeders from the sky.”

A despairing cry broke from the girl’s throat.

De Guzmán turned and groped his way down the stairs, a pistol in each hand. Just as he reached a lower landing, he heard the girl cry out again, with greater poignancy, and with the cry the dry rustle of great wings. He came through a door and saw a nightmare shape settling down on the altar—a dragon-like thing from the upper spaces of the air, whose raids on the lower levels, ages ago, gave rise to tales of harpies and vampires.

De Guzmán stepped through the door and fired point-blank with his right-hand pistol, and the monster rolled to the floor, its head blasted. He wheeled. A man had risen from the throne, and though he had expected to see a monstrosity, the Spaniard’s flesh crawled—not because the man was hideous, for he was handsome with a terrible dark beauty; but because of the ageless evil in his luminous dark eyes.

“Fool!” said he, calmly, “I am Nekht Semerkeht of Egypt!”

Even as he glimpsed the motion de Guzmán fired point-blank with his left-hand pistol, and Nekht Semerkeht reeled with a choking cry. He staggered back and vanished through the wall. De Guzmán unbound the girl. She cried out for him to follow. He followed, through strange corridors until he came to a vast chamber where about the walls were ranged bodies of men upright, and turned to stone—Toltecs, Aztecs, Totonacs, Tonkewas, Lipans, Apaches, warriors of tribes unfamiliar to the Spaniard.

Nekht Semerkeht sat at a smooth stone table, a slight smile of seeming self-mockery on his dark lips, his red-stained hand against his breast.

“You have conquered,” he said. “I am dying.” De Guzmán sat the cresset on the table. “I am Nekht Semerkeht of Egypt. The Ptolemies drove me from Egypt long ago. My galley was wrecked off the coast of Mexico. My arts were strong then. They are stronger now. I made myself lord of Mexico, but I wearied of its rule and came northward. I have heard how your race slew Montezuma. But here in this city are greater treasures of gold than ever Cortez took from Tenochtitlan.”

As they talked de Guzmán was aware of a magic web surrounding him. He broke it, leaped up, and Nekht Semerkeht was on him with a curved sword.

“Fool!” roared the Egyptian. “Did you think a pellet of lead could slay Nekht Semerkeht?”

His blade was a white flame about the Spaniard’s bare head, and as de Guzmán parried and smote, he saw the cresset was dimming, going out. He rushed, smiting desperately to strike down this dark fiend before the blackness engulfed them. Sparks rang and Nekht Semerkeht cried out as he pitched backward into the blackness yawning at his feet. Blood spurting he toppled and vanished. The trap door closed, and de Guzmán stood alone in the hall of the warriors.

He turned and ran out of the accursed place. The great doors were rushing shut. He sprang through and they clanged behind him.

He sought Nezahualca and claimed his part of the kingship. She resisted but he overpowered her. Then as he slept Nekht Semerkeht came to him and assumed the likeness of a strange Indian warrior and told the Spaniard he would bring the Comanches upon the city by means of a dream, and that his race would never be able to conquer them. The Comanches came upon them and Nekht Semerkeht, dying, dragged himself upon the palace tower and smote on a gong until a section of the wall fell. The Comanches swarmed in and butchered everyone in the city. De Guzmán fell fighting fiercely.