Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

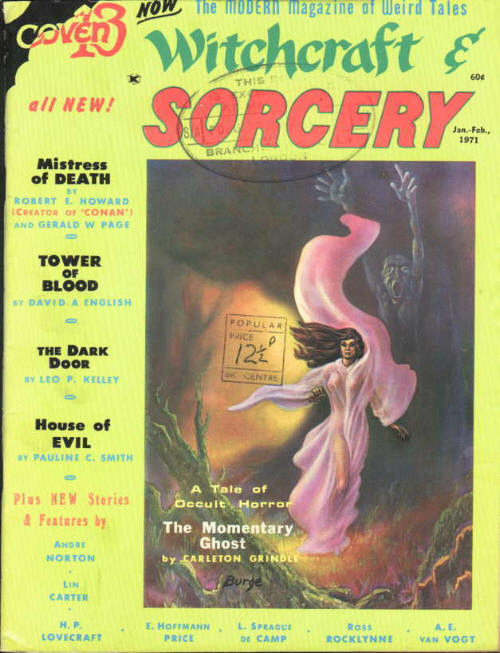

Published in Witchcraft & Sorcery, Vol. 1, No. 5 (January-February 1971).

(Fragment; completed by Gerald W. Page.)

Ahead of me in the dark alley, steel clashed and a man cried out as men cry only when death-stricken. Around a corner of the winding way three mantled shapes came running, blindly, as men run in panic and terror. I drew back against the wall to let them go past, and two crowded by me without even seeing me, breathing in hysterical gasps; but the third, running with his chin on his shoulder, blundered full against me.

He shrieked like a damned soul, and evidently deeming himself attacked, grappled me wildly, tearing at me with his teeth like a mad dog. With a curse I broke his grasp and flung him from me against the wall, but the violence of my exertion caused my foot to slip in a puddle on the stones, and I stumbled and went to my knee.

He fled screaming on up the alley, but as I rose, a tall figure loomed above me, like a phantom out of the deeper shadows. The light of a distant cresset gleamed dully on his morion and the sword lifted above my head. I barely had time to parry the stroke; the sparks flew as our steel met, and I returned the stroke with a thrust of such violence that my point drove through teeth and neck and rang against the lining of his steel head-piece.

Who my attackers were I knew not, but there was no time for parley or explanation. Dim figures were upon me in the semi-darkness and blades whickered about my head. A stroke that clanged full upon my morion filled my eyes with sparks of fire, and abandoning the point in my extremity, I hewed right and left and heard men grunt and curse as my sword’s edge gashed them. Then, as I stepped back to avoid a swiping cut, my foot caught in the cloak of the man I had killed, and I fell sprawling over the corpse.

There was a fierce cry of triumph, and one sprang forward, sword lifted—but ere he could strike or I could lift my blade above my head, a quick step sounded behind me, a dim figure loomed in the uncertain light, and the downward sweeping blade rang on a sword in mid-air.

“Dog!” quoth the stranger with curious accent. “Will you strike a fallen man?”

The other roared and cut at him madly, but by that time I was on my feet again, and as the others pressed in, I met them with point and edge, thrusting and slashing like a demon, for I was wild with fury at having been in such a plight as the stranger rescued me from. A side-long glance showed me the latter driving his sword through the body of the man who opposed him, and at this, and as I pressed them, drawing blood at each stroke, the rogues gave way and fled fleetly down the alley.

I turned then to my unknown friend, and saw a lithe, compactly-built man but little taller than myself. The glare of the distant cresset fell dimly upon him, and I saw that he was clad in fine Cordovan boots and velvet doublet, beneath which I glimpsed a glint of fine mesh-mail. A fine crimson cloak was flung over his shoulder, a feathered cap on his head, and beneath this his eyes, cold and light, danced restlessly. His face was clean-shaven and brown, with high cheekbones and thin lips, and there were scars that hinted of an adventurous career. He bore himself with something of a swagger, and his every action betokened steel-spring muscles and the coordination of a swordsman.

“I thank you, my friend,” quoth I. “Well for me that you came at the moment which you did.”

“Zounds!” cried he. “Think naught of it. ’Twas no more than I’d have done for any man—but, Saint Andrew! You’re a woman!”

There being no reply to that, I cleaned my blade and sheathed it, while he gaped at me openmouthed.

“Agnes de la Fere!” he said slowly, at length. “It can be no other. I have heard of you, even in Scotland. Your hand, girl! I have yearned to meet you. Nor is it an unworthy thing even for Dark Agnes to shake the hand of John Stuart.”

I grasped his hand, though in sooth, I had never heard of him, feeling steely thews in his fingers and a quick nervous grip that told me of a passionate, hair-trigger nature.

“Who were these rogues who sought your life?” he asked.

“I have many enemies,” I answered, “but I think these were mere skulking rogues, robbers and murderers. They were pursuing three men, and I think tried to cut my throat to hush my tongue."

“Likely enough,” quoth he. “I saw three men in black mantles flee out of the alley mouth as though Satan were at their heels, which aroused my curiosity, so I came to see what was forward, especially as I heard the rattle of steel. Saint Andrew! Men said your sword-play was like summer lightning, and it is even as they said! But let us see if the rogues have indeed fled or are merely lurking beyond that crook to stab us in the back as we depart.”

He stepped cautiously around the crook and swore under his breath.

“They are gone, in sooth, but I see something lying in the alley. I think it is a dead man.”

Then I remembered the cry I heard, and I joined him. A few moments later we were bending over two forms that lay sprawled in the mud of the alley. One was a small man, mantled like the three who had fled, but with a deep gash in his breast that had let out his life. But as I spoke to Stuart on the matter, he swore suddenly. He had turned the other man on his back, and was staring at him in surprise.

“This man has been dead for hours,” quoth he. “Moreover he died not by sword or pistol. Look! It is the mark of the gallows! And he is clad still in the gibbet-shirt. By Saint Andrew, Agnes, do you know who this is?” And when I shook my head, “It is Costranno, the Italian sorcerer, who was hanged at dawn this morning on the gibbet outside the walls, for practicing the black arts. He it was who poisoned the son of the Duke of Tours and caused the blame to be laid upon an innocent man. But Françoise de Bretagny, suspecting the truth, trapped him into a confession to her, and laid the facts before the authorities.”

“I heard something of this matter,” quoth I. “But I have been in Chartres only a matter of a week.”

“It is Costranno, well enough,” said Stuart, shaking his head. “His features are so distorted I would not have known him, save that the middle finger of his left hand is missing. And this other is Jacques Pelligny, his pupil in the black arts. Sentence of death was passed on him, likewise, but he had fled and could not be found. Well, his art did not save him from a footpad’s sword. Costranno’s followers have cut him down from the gibbet—but why should they have brought the body back into the city?”

“There is something in Pelligny’s hand,” I said, prying the dead fingers apart. It was as if, even in death, they gripped what they held. It was a fragment of gold chain, and fastened to it a most curious red jewel that gleamed in the darkness like an angry eye.

“Saint Andrew!” muttered Stuart. “A rare stone, i’ faith—hark!” he started to his feet. “The watch! We must not be found by these corpses!”

Far down the alley I saw the glow of moving lanthorns and heard the tramp of mailed feet. As I scrambled up, the jewel and chain slipped from my fingers—it was almost as if they were snatched from my hand—and fell full on the breast of the dead sorcerer. I did not wish to take the time to retrieve it; so I hurried up the alley after Stuart, and glancing back, I saw the jewel glittering like a crimson star on the dead man’s bosom.

Emerging from the alley into a narrow winding street, scarcely better lighted, we hurried along it until we came to an inn, and entered it. Then, seating ourselves at a table somewhat apart from the others who wrangled and cast dice on the wine-stained boards, we called for wine and the host brought us two great jacks.

“To our better acquaintance,” quoth John Stuart, lifting his tankard. “By Saint Andrew, now that I see you in the light; I admire you the more. You are a fine, tall woman, but even in morion, doublet, trunk-hose and boots, none could mistake you for a man. Well are you called Dark Agnes! For all your red hair and fair skin there is something strange and dark about you. Men say you move through life like one of the Fates, unmoved, unchangeable, potent with tragedy and doom, and that the men who ride with you do not live long. Tell me, girl, why did you don breeks and take the road of men?”

I shook my head, unable to say myself, but as he urged me to tell him something of myself, I said, “My name is Agnes de Chastillon, and I was born in the village of La Fere, in Normandy. My father is the bastard son of the Duc de Chastillon and a peasant woman—a mercenary soldier of the Free Companies until he grew too old to march and fight. If I had not been tougher than most he would have killed me with his beating before I was grown. When at last he sought to marry me to a man I hated, I killed that man, and fled from the village. One Etienne Villiers befriended me, but also taught me that a helpless woman is fair prey to all men, and when I bested him in even fight, I learned that I was as strong as most men, and quicker.

“Later I fell in with Guiscard de Clisson, a leader of the Free Companies, who taught me the use of the sword before he was slain in an ambush. I took naturally to the life of a man, and can drink, swear, march, fight and boast with the best of them. I have yet to meet my equal at sword play.”

Stuart scowled slightly as if my word did not please him overmuch, and he lifted his tankard, quaffed deeply, and said, “There be as good men in Scotland as in France, and there men say that John Stuart’s blade is not made of straw. But who is this?”

The door had opened and a gust of cold wind made the candles flicker, and sent a shiver over the men on the settles. A tall man entered, closing the door behind him. He was wrapped in a wide black mantle, and when he raised his head and his glance roved over the tavern, a silence fell suddenly. That face was strange and unnatural in appearance, being so dark in hue that it was almost black. His eyes were strange, murky and staring. I saw several topers cross themselves as they met his gaze, and then he seated himself at a table in a corner furthest from the candles, and drew his mantle closer about him, though the night was warm. He took the tankard proffered him by an apprehensive slattern and bent his head over it, so his face was no longer visible under his slouch hat, and the hum of the tavern began again, though somewhat subdued.

“Blood on that mantle,” said John Stuart. “If that man be not a cutthroat, then I am much befooled. Host, another bottle!”

“You are the first Scotsman I ever met,” said I, “though I have had dealings with Englishmen.”

“A curse on the breed!” he cried. “The devil take them all into his keeping! And a curse on my enemies who exiled me from Scotland.”

“You are an exile?” I asked.

“Aye! With scant gold in my sporran. But fortune ever favors the brave.” And he laid hand on the hilt at his hip.

But I was watching the stranger in the corner, and Stuart turned to stare at him. The man had lifted his hand and crooked a finger at the fat host, and that rogue drew nigh, wiping his hands on his leathern apron and uneasy in his expression. There was something about the black mantled stranger that repelled men.

The stranger spoke, but his words were a mumble and mine host shook his head in the bewilderment.

“An Italian,” muttered Stuart. “I know that jabber anywhere.”

But the stranger shifted into French and as he spoke, haltingly, his words grew plainer, his voice fuller.

“Françoise de Bretagny,” quoth he, and repeated the name several times. “Where is the house of Françoise de Bretagny?”

The inn-keeper began giving him directions, and Stuart muttered: “Why should that ill-visaged Italian rogue desire to go to Françoise de Bretagny?”

“From what I hear,” I answered cynically, “it is no great surprise to hear any man asking for her house.”

“Lies are always told about beautiful women,” answered Stuart, lifting his tankard. “Because she is said to be the mistress of the Duc of Orléans does not mean that she—”

He froze suddenly, tankard to lip, staring, and I saw an expression of surprise pass over his brown, scarred face. At that moment the Italian had risen, and drawing his wide mantle about him, made for the door.

“Stop him!” roared Stuart, leaping to his feet, and dragging out his sword. “Stop that rogue!”

But at that instant a band of soldiers in morions and breastplates came shouldering in, and the Italian glided out past them and shut the door behind him. Stuart started forward with a curse, to halt as the soldiers barred the way. Striding into the center of the tavern, and roving a stern glance over all the cringing occupants, the captain, a tall man in a gleaming breastplate, said loudly: “Agnes de La Fere, I arrest you for the murder of Jacques Pelligny!”

“What do you mean, Tristan?” I exclaimed angrily, springing up. “I did not kill Pelligny!”

“This woman saw you leave the alley where the man was slain,” answered he, indicating a tall, fair wench in feathers and beads who cowered in the grasp of a burly man-at-arms and would not meet my gaze. I knew her well, a courtesan whom I had befriended, and whom I would not have expected to give false testimony against me.

“Then she must have seen me too,” quoth John Stuart, “for I was with Agnes. If you arrest her you must arrest me too, and by Saint Andrew, my sword will have something to say about that.”

“I have naught to do with you,” answered Tristan. “My business is with this woman.”

“Man, you are a fool,” cried Stuart gustily. “She did not kill Pelligny. And what if she did? Was not the rogue under sentence of death?”

“He was meat for the hangman, not the private citizen,” answered Tristan.

“Listen,” said Stuart. “He was slain by footpads, who then attacked Agnes who chanced to be traversing the alley at the time. I came to her aid, and we slew two of the rogues. Did you not find their bodies, with masks to their heads to prove their trades?”

“We saw no such thing,” answered Tristan. “Nor were you seen thereabouts, so your testimony is without value. This woman here saw Agnes de La Fere pursue Pelligny into the alley and there stab him. So I am forced to take her to the prison.”

“I know well why you wish to arrest me, Tristan,” I said coldly, approaching him with an easy tread. “I had not been to Chartres a day before you sought to make me your mistress. Now you take this revenge upon me. Fool! I am mistress only to Death!”

“Enough of this idle talk,” ordered Tristan curtly. “Seize her, men!” It was his last command on earth, for my sword was through him before he could lift his hand. The guard closed in on me with a yell, and as I thrust and parried, John Stuart sprang to my side and in an instant the inn was a madhouse, with stamping boots, clanging blades and the curses and yells of slaughter. Then we broke through, leaving the floor strewn with corpses, and gained the street. As we broke through the door I saw the wench they brought to testify against me cowering behind an overturned settle and I grasped her thick yellow locks and dragged her with me into the street.

“Down that alley,” gasped John Stuart. “Other guardsmen will be here anon. Saint Andrew, Agnes, will you burden yourself with that big hussy? We must take to our heels!”

“I have a score to settle with her,” I gritted, for all my hot blood was roused. I hauled her along with us until we made a turn in the alley and halted for breath.

“Watch the street,” I bade him, and then turning to the cowering wench, I said in calm fury: “Margot, if an open enemy deserves a thrust of steel, what fate does a traitress deserve? Not four days agone I saved you from a beating at the hands of a drunken soldier, and gave you money because your tears touched my foolish compassion. By Saint Trignan, I have a mind to cut the head from your fair shoulders!”

“Oh, Agnes,” she sobbed, falling to her knees, and clasping my legs. “Have mercy, I—”

“I’ll spare your worthless life,” I said angrily, beginning to unsling my sword belt. “But I mean to turn up your petticoats and whip you as no beadle ever did.”

“Nay, Agnes!” she wailed. “First hear me! I did not lie! It is true that I saw you and the Scotsman coming from the alley with naked swords in your hands. But the watch said merely that three bodies were lying in the alley, and two were masked, showing they were thieves. Tristan said whoever slew them did a good night’s work, and asked me if I had seen any coming from the alley. So I thought no harm, and replied that I saw you and the Scotsman John Stuart. But when I spoke your name, he smiled and told his men that he had his reasons for desiring to get Agnes de La Fere in a dungeon, helpless and unarmed, and bade them do as he told them. So he told me that my testimony about you would be accepted, but the rest, about John Stuart, and the two thieves, he would not accept. And he threatened me so terribly that I dared not defy him.”

“The foul dog,” I muttered. “Well, there is a new captain of the watch in hell tonight.”

“But you said three bodies,” broke in John Stuart. “Were there not four? Pelligny, two thieves, and the body of Costranno?”

She shook her head.

“I saw the bodies. There were but three. Pelligny lay deep in the alley, fully clad, the other two around the crook, and the larger was naked.”

“Eh?” ejaculated Stuart. “By Heaven, that Italian! I have but now remembered! On, to the house of Françoise de Bretagny!”

“Why there?” I demanded.

“When the Italian in the inn drew his cloak about him to depart,” answered Stuart, “I glimpsed on his breast a fragment of golden chain and a great red jewel—I believe the very jewel Pelligny grasped in his hand when we found him. I believe that man is a friend of Costranno’s, a magician come to take vengeance on Françoise de Bretagny! Come!”

He set impetuously off up the alley, and I followed him, while the girl Margot scurried away in another direction, evidently glad to get off with a whole skin.

Stuart led the way, grimly silent, and I followed after him, somewhat perplexed by his silence and the silence of the street. For strangely silent were the dark, twisting streets, silent even for night. Involuntarily, I shuddered, though whether at the silence of the cold, I could not say. We encountered no one, not even soldiers, on our way to the home of Françoise de Bretagny.

It was not far to her home from the tavern where we fled the watch, though the tavern lay huddled among the squalor of the town’s least reputable quarter and the home of Françoise de Bretagny, as befitted so magnificent a structure, was in a neighborhood suitable to the wealthiest noblewoman. No lights shone in the windows as we approached, and indeed none of the neighbor houses were lit at this time of night. We paused, John Stuart and I, without the courtyard gate and strained our ears, but the silence beat on us like the darkness, oppressive and threatening.

It was John Stuart who reached forward and pushed the gate, which opened noiselessly at his touch.

“Ah!” said he a moment later. “The lock’s been broken and within the half hour, I’ll wager.”

“Inside, then,” I replied, barely able to keep my voice to a whisper. “Even now we may be too late!”

“Aye,” Stuart said, shoving the gate open the rest of the way. I heard the rasp of steel against scabbard as he drew his sword, and the dark shadow that was John Stuart’s form moved agilely through the gate and I followed after. Within the courtyard it was as still as it was without, but there were thicker shadows here, for around us grew trees and thick shrubbery, as still as dark statues in the breeze-calmed night.

“Saint Andrew!” I heard John Stuart exclaim, and saw the dark form of his body bend and crouch to the ground, bending over something—or someone. I moved to his side and peered down.

It was at that moment that the moon chose to come out, and I saw that we were bending over the corpse of a man, who, by his dress and his presence in the courtyard, I took to be a servant of Françoise de Bretagny.

“Does he live?” I asked.

“Nay,” replied John Stuart. “Strangled, by the look of his face and the marks on his throat—strange, those marks. There’s something about them out of the ordinary. Have you flint and steel, lass?”

For answer, I drew flint and steel from the pouch at my waist and struck sharply. Briefly a spark flared, bathing the bloated face of the corpse in pale yellow light. Briefly, but long enough to show us what we saw. I gasped at the sight of the marks on the dead man’s throat.

“By all that the Saints hold sacred,” John Stuart said. “ ’Tis an enemy we’re against that I would rather not be facing, Dark Agnes. For such is my thought. Mayhap ye’d best go back and find your way out of this cursed town—”

“What was it you saw, John Stuart?”

“Have you not eyes of your own, lass?”

“I saw—but I would hear it from your lips.”

“Then hear it. I saw the marks of a hand against the throat of this corpse, and the marks of that hand were missing a finger.”

“The hand of the dead sorcerer Costranno?” I said. “But how could that be? We saw him dead, the marks of the rope as plain upon his neck as the marks of the hand upon this poor man’s neck.”

“That jewel—” John Stuart said. “Saint Andrew! A magician is out to avenge Costranno, but it is not a friend of his but Costranno himself. Necromancy is the only answer. That alleyway where you were attacked. I have heard that the stones paving that alley were taken from an ancient heathen temple that once stood in a grove outside the city.

“It leaves me cold to think on it, but if but a tenth the tales related about Costranno be true, then he’s magician enough to accomplish this and more. Mayhap his friends were not bearing him to his own house, but to that alley with its heathen temple’s stones. Aye, mayhap they cut him from the gallows and were bringing him there. Likely Pelligny had even spoke the incantation to bring the dead to life when those footpads interrupted before he could place the jewel—the last step in the ritual. And that was accomplished when the jewel fell from your fingers on to the breast of the corpse.”

“The holy saints!” I cried. “Then, I am a part of this. But even so, I swear that jewel slipped not from my fingers, but was yanked by something, some power!”

“By something from beyond the grave,” Stuart said grimly, as he rose. “Now you go back and find your way to the waterfront and flee this city, for the watch will want your throat for a gibbet noose if you remain in Chartres.”

“I cannot flee, for whatever snatched that jewel from my hands has made me an accomplice to necromancy and blasphemy,” I said, resenting also the implication that I should flee from danger while John Stuart stayed to face it. “Two against one will not be too great odds when the one is a magician returned from the grave.”

John Stuart paused, and I half expected argument. But instead he said, “There’s little time then. Costranno, once back from the dead, must have stripped the clothes from the thief’s corpse and set out straightway to find Françoise de Bretagny. We are lucky he chose the tavern we were in to ask directions, though he must have known this house from the stories I have heard.”

“But not the quarter of the city he was in,” I said. “It was a quarter populous with thieves and cutthroats, but they had no truck with Costranno, nor he with them. Let us hurry. Even now we may be too late!”

We found the door to the house open like the courtyard gate. I found candles and lit one. We were in a large parlor, splendidly furnished in a way that bespoke a householder of great wealth. But there was not time to note the splendor of the room and its hangings.

“This way,” John Stuart said. He headed for the stairs and I followed after him.

We reached the top of the stairs, where the candle cast flickering red light among the black shadows of a narrow hallway. For but a second John Stuart paused, then pointed and said, “That door!”

At the end of the hall there was an open door. He rushed toward it and I followed after him, almost causing the candle to flicker out in my haste.

The room beyond the open door was a bedchamber, a lady’s bedchamber, fully as lavish in its appointments as the parlor below. The bed was empty and the covers thrown onto the floor. Furniture was overturned and a mirror broken, as if some thrown object had struck it instead of the target it was meant for. There was no sign of Françoise de Bretagny, nor of Costranno.

“What sorcery is this? Has he vanished into the air and taken her with him?” I said. “They couldn’t have gotten past us.”

A noise came from the darkness at my side, so sudden and unexpected that I almost dropped the candle as I whirled to face the source of the sound. I held the candle high to bathe a dark corner with light, and there in the corner was a man, cowering and gibbering, as a frightened child might gibber.

The man drew back against the wall as John Stuart approached him. The servant uttered sounds but they were meaningless sounds, such as are not pleasant to hear from the lips of a living man. I felt a shudder pass involuntarily up my spine and saw that even John Stuart was slightly unnerved by this, for as he turned back to face me the light from the candle was sufficient to show the strain upon his face.

“His mind is gone,” Stuart said. He stood for a moment, those piercing eyes of his sweeping the room in a way that almost convinced me those shadows could conceal naught from him. “Aye,” he said suddenly. “It’s all so plain to me now. Obviously Françoise de Bretagny saw the need for protection, because both the servants we have seen were dressed and obviously set to guard her through the night. But the magnitude of the danger that beset her she did not begin to guess, else she would have fled the city—and indeed all of France. For now one of her servant-guards lies dead and the other’s mind has fled him at the sight of a dead man carrying off his mistress. And she has been taken—but who can say where?”

“More than likely,” I said, “it is too late now to save Françoise de Bretagny though we can avenge her murder.”

“There may be time,” John Stuart said, “if we make haste!” He began moving around the room, peering here and there, tapping the walls, feeling along the woodwork and behind hangings. “My guess is that Costranno has more sinister plans for her than murder, else her corpse would be sprawled across that bed. It may even be that some further ritual is necessary to fully revive him from the dead and that he has marked Françoise de Bretagny for that foul ceremony. Ah! What is this?”

His hand had reached behind a torn hanging and I could see that he moved something, though what it was he moved was hidden to me by the hanging. But as he moved it, a part of the wall moved out, revealing a passageway and beyond the passageway, a stair, leading down.

“This is how our necromancer made his escape,” John Stuart said. From near the door, the maddened servant increased his gibbering, more frightened now than before. “Aye!” said John Stuart. “Our friend knows about this opening.”

He stepped through the opening and I followed after him, holding high the candle to cast its light before us. “It is likely Françoise de Bretagny knew naught of this passageway,” John Stuart said. “It may be that the entire city of Chartres is combed with passageways known only to Costranno and a few others.”

“That is not a cheering thought,” I said. “But I’ve a feeling there is more to it than I care for there to be.”

The stairs were stone, seemingly carved from solid rock, leading down far below the level of the street, far deeper I felt than any cellar or dungeon in the city would be expected to go. The stairs wound down into the earth until I thought they would lead to hell itself, and then, ahead and below, we saw a light coming through a doorway at the foot of the stairs.

We paused momentarily upon the stairs and I strained my ears against the silence. For a moment it seemed deathly still, but then I thought a sound did come to me—the sound of a voice, perhaps, but too faint and muffled by distance and thick stone walls for me to be certain it was not the growling of some beast.

I snuffed out the candle I held and laid it carefully on the stairs. I was certain that the thickness of the walls around us would hide the sound of a candle dropping from any human ears, but I was not so certain that the ears the sound should be hidden from were human.

I drew my sword and followed John Stuart down the stairs.

We reached the bottom of the stairs and beyond the open door we saw a crypt, brightly lighted by torches set into brackets in the wall. I call it a crypt because there were caskets, or what appeared to be caskets, set into niches in the wall. But the writings and designs carved on these caskets and on the wall were not Christian, nor of any religion with which I am familiar. In the center of the crypt there was a dais of black marble and on the dais, naked and unconscious, but still breathing, lay Françoise de Bretagny. And a few feet away from the dais, Costranno himself knelt, straining to lift a seven sided stone in the floor. As we rushed through the doorway he saw us and gave one fierce inhuman effort that dragged the stone out of the floor and to one side, revealing a black, gaping hole.

Costranno’s cloak was thrown off now, and his features, hidden to us in the tavern, were now revealed in the torchlight. The gibbet had done its work well. Bloated was the face of Costranno, his lips blacked with death had the marks and bite of the rope heavy upon his neck. He gave a great, incoherent cry as John Stuart moved toward him. Then the sorcerer fell back to the wall behind him and snatched a torch from its bracket. His unearthly, garbled voice rose in a shout that might have been rage or a call to the blasphemous gods he worshipped, and he threw the torch at Stuart.

The torch struck the brown stone flooring before John Stuart’s feet with a shower of sparks and flames and a sudden billowing of black smoke. Instantly Stuart’s figure was hidden from my view, but I could hear his voice, giving vent to his rage in a string of curses. The smoke was gone almost as suddenly as it came and Stuart still stood, apparently unhurt. But when he moved to leap at Costranno, something seemed to hold him back, as if an invisible wall had formed.

I spent no time in trying to fathom Costranno’s magic. Before the sorcerer could reach another torch, I was upon him. And as Stuart cursed and raved because he could not move to hurl himself and his sword point upon his foe, I passed my sword twice through the undead man’s body without harming him.

A horrible, angry cry came forth from Costranno’s mangled throat. He drew his sword, and only my mail shirt beneath my doublet saved me from his terrible thrusts. But even so I was forced back, and the growling, snarling Costranno bore toward me, his sword slashing and beating at me with such terrific blows that I was hard put to parry.

I knew fear at that moment—icy, nerve-shattering fear that seemed to grip my very soul, and rendered me so senseless that I fought by instinct and main strength and without science or technique, save that of the moment. Costranno was in a rage and wanted my life and the life of John Stuart and of the naked, helpless girl who lay as intended sacrifice upon the black altar.

I did not realize his strategy until the heel of my left foot reached the edge of the opening in the floor behind me. Costranno had forced my back, hoping not to best me with the sword, but to hurtle me into the abyss. I knew nothing of what might be at the bottom of that pit, but somehow I knew that the kindest death that could befall one who toppled into it would be to have his body dashed to pieces at its bottom. I felt, but whatever power I cannot say, that there was something in that pit which I did not care to meet—and my fear became blind, unreasoning panic. And that is what saved me.

I hacked fiercely at Costranno, counting more on strength than skill, and in that moment drove him back far enough to give me the room I needed. I dove to one side, rolled and came to my feet behind him. I struck with all my strength, and the edge of my blade cut deep into the flesh of Costranno’s mangled neck, severing through bone and gristle as well as flesh, and then pulling free as the severed head flopped from the shoulder of the corpse—and into the gaping blackness of the hole into which he had tried to push me.

There was an unearthly cry of terror from the blackness beneath the feet of the still standing corpse. Costranno’s headless body stood for a moment at the edge of the pit and then one foot moved back, away from the edge.

My fear had become so agonizing that I was almost mindless, but somehow I saw what must be done and somehow brought myself to do it, despite the revulsion the thought of touching Costranno brought to me. I have fought many times and killed many men and seen many comrades die in battle. I have carried many a corpse to a shallow battlefield grave with no compunction about touching cold flesh. But the thought of touching a walking dead man was abhorrent in the extreme to me.

But it was necessary that I touch it so that it could not touch me. I forced myself to run up behind the shambling corpse and shove my hands hard against its shoulders. Something like a blast of lightning coursed through my body and threw me back, numbly, to the floor. But even as I fell to the floor, I saw the headless corpse topple into the pit.

For a moment there was silence in the chamber and neither Stuart or I moved. Then, on the altar, Françoise de Bretagny stirred and made a small, whimpering sound as consciousness started to return to her. John Stuart, free now of the spell which had imprisoned him, rushed to my side and reached down to aid me to my feet.

Suddenly shame at the womanly fear I had felt while fighting Costranno flooded me. Flustered, I shook off his hand and rose to my feet, unsteadily, but without help. “I’m all right,” I said. “I can take care of myself.”

John Stuart laughed, but there was oddly nothing of contempt or malice in his laugh. “You are more a woman than you’ll admit,” he said. “And to your credit, Agnes de La Fere.”

“If you would aid a helpless woman,” I said, with discomfort, “then see to Françoise de Bretagny. My guess is we will need such influence as she can give us to gain protection from the watch before we escape this city.”

“Aye,” John Stuart said. “There is truth in what you say,” He went to see to Françoise, and I stood, trying to conceal my nervousness, staring at the open pit in the floor.

I went to the wall and took a torch from a bracket and went to the edge of the opening and knelt down. I held the torch out over the opening and peered down into the blackness.

Before I knew what was happening, a snaky, black fur-covered arm reached out and grasped my doublet. I screamed as the arm strove to drag me into the hole and I beat down with the torch. There was a bestial cry and the thing let go. I had only a glimpse of a distorted, apish thing falling and the torch fell after, dwindling to a speck of light far below, like a meteor. I whimpered like a child and turned away from the pit into the welcome arms of John Stuart that closed about me like the protecting arms of some saint. And without shame I shivered for a time in those arms as my fear took hold of me and ran its course.

“It’s over now, Dark Agnes,” I heard the soothing deep voice of John Stuart. “And now you have naught to fear—and naught to be ashamed of. You have done as well against this horror as any woman or any man could do. And if, in the end, it comes to this, there is no shame for you to act as a woman, Dark Agnes, for you are quite a woman, indeed.”

I did not object as he lifted me to my feet. “And it may chance,” he went on, his voice now lighter and with that familiar hint of laughter to it, “that when you ride forth from this city, you will find me riding at your side.”

“Do not forget the curse that hangs over me, John Stuart. Does it not bother you that the men who ride with Dark Agnes ride to an early grave?”

“Not a bit,” John Stuart said, with booming laughter. “For what is another curse, more or less, upon the head of a Stuart!”

And together we replaced the stone slab in the opening in the floor and then helped Françoise de Bretagny from the crypt and up the stairs back to her own bedchamber, leaving behind the horror that pursued her.