Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

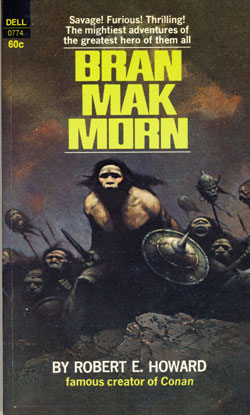

Published in Bran Mak Morn, 1969.

From the dim red dawn of Creation,

From the fogs of timeless Time

Came we, the first great nation,

First on the upward climb.

Savage, untaught, unknowing,

Groping through primitive night,

Yet faintly catching the glowing,

The hint of the coming Light.

Ranging o’er lands untraveled,

Sailing o’er seas unknown;

Mazed by world-puzzles unraveled,

Building our land-marks of stone.

Vaguely grasping at glory,

Gazing beyond our ken;

Mutely the ages story,

Rearing on plain and fen.

See, how the Lost Fire smolders,

We are one with the eons’ must.

Nations have trod our shoulders,

Trampling us into the dust.

We, the first of the races,

Linking the Old and New—

Look, where the sea-cloud spaces

Mingle with ocean-blue.

So we have mingled with ages,

And the world-wind our ashes stirs,

Vanished are we from Time’s pages,

Our memory? Wind in the firs.

Stonehenge of long gone glory

Sombre and lone in the night

Murmur the age-old story

How we kindled the first of the Light.

Speak night-winds, of man’s creation,

Whisper o’er crag and fen,

The tale of the first great nation,

The last of the Stone Age men.

Sword met sword with clash and slither.

“Ailla! A-a-ailla!” rising on a steep pitch of sound from a hundred savage throats.

On all sides they swarmed upon us, a hundred to thirty. Back to back we stood, shields lapped, blades at guard. Those blades were red, but corselets and helmets, too, were red. One advantage we possessed: we were armored and our foes were not. Yet they flung themselves naked to the fray with as fierce a valor as if they were clad in steel.

Then for a moment they drew off and stood at a distance, gasping curses, blood from sword thrusts making strange patterns on their woad-painted skins.

Thirty men! Thirty, the remnant of the troop of five hundred that had marched so arrogantly from Hadrian’s Wall. Zeus, what a plan! Five hundred men, sent forth to hew a way through a land that swarmed with barbarians of another age. Marching over heather hills by day, hacking a crimson trail through blood-frenzied hordes, close camp at night, with snarling, gibbering beings that stole past the sentries to slay with silent dagger. Battle, bloodshed, carnage.

And word would go to the emperor in his fine palace, among his nobles and women, that another expedition had disappeared among the hazy mountains of the mystic North.

I glanced at the men who were my comrades. There were Romans from Latinia and native-born Romans. There were Britons, Germans, and a flame haired Hibernian. I looked at the wolves in human guise that ringed us round. Dwarfish, hairy men, they were, bowed and gnarled of limb, long and mighty of arm, with great mops of coarse hair topping foreheads that slanted like apes’. Small unblinking black eyes glinted malevolent spite, like a snake’s eyes. Scarce any clothing they wore, and they bore small round shields, long spears, and short swords with oval-shaped blades. While scarce one of them topped five feet in height, their incredibly broad shoulders denoted massive strength. And they were as quick as cats.

They came with a rush. Short savage sword clashed on short Roman sword. It was fighting at very close quarters, for the savages were better adapted to such battling, and the Romans trained their soldiers in the use of the short blade. There the Roman shield was at disadvantage, for it was too heavy to be shifted swiftly, and the savages crouched, thrusting upward.

Back to back we stood, and as a man fell, we closed the ranks again. On, on they pushed, until their snarling faces were close to ours, and their rank, beast-like breath was in our nostrils. Like men of steel we held the formation. The heather, the hills, time itself, faded. A man ceased to be a man and became a mere fighting automaton. The haze of battle erased mind and soul. Swing, thrust. A blade shattering on shield; a bestial face snarling through the battle-fog. Smite! The face vanishing for another face equally bestial.

Years of Roman culture slipped away like seafog before the sun. I was again a savage; a primal man of the forest and seas. A primal man, facing a tribe of another age, fierce in tribal hate, fierce with the slaughter-lust. How I cursed the shortness of the Roman sword I wielded. A spear crashed against my breastplate; a sword shattered on my helmet crest, beating me to the ground. Up I reeled, slaying the smiter with a fierce up-slashing thrust. Then I stopped short, sword raised. Over all the heather was silence. No more foes stood before me. In a silent, gory band they lay, still grasping their swords, hacked and hewn faces still set in snarls of hate. And of the thirty that had faced them, there remained five.Two Romans, a Briton, the Irishman, and I. The Roman sword and the Roman armor had triumphed and incredible as it seemed, we had slain nearly four times our own number.

And there was but one thing we might do. Hew our way back over the trail we had come, seek to gain through countless leagues of ferocious land. On every hand great mountains reared. Snow crowned their summits, and the land was not warm. How far north we were, we had no idea. The march was but a hazy memory into whose crimson fogs days and nights faded in a red panorama. All we knew was somedays agone the remnants of the Roman army had been scattered among the peaks by a terrific tempest, on whose mighty wings the savages had assailed us by hordes. And the war horns had droned through the vales and crags for days, and the half-hundred of us who had held together had battled every step of the way, beset by yelling foemen who seemed to swarm from thin air. Now silence reigned and there was no sign of the tribesmen. South we headed, going like hunted things.

But before we set out, I found upon the battlefield that which thrilled me with a fierce joy. Grasped in the hand of a tribesman was a long, two-handed sword. A Norse sword, by the hand of Thor! How the savages came by it, I know not. Possibly some yellow-haired Viking had gone down among them, battlesong on bearded lips, sword swinging. But at least the sword was there.

So fiercely had the savage clinched the hilt that I was forced to chop off his hand to gain the sword.

With it in my grasp I felt bolder. Short swords and shields might suffice for men of middle height; but they were feeble arms for a warrior who towered more than five inches above six feet.

Over the mountains we went, clinging to narrow cliff edges, scaling steep crags. Like so many insects we crawled along the face of a sky-towering precipice, of such gigantic proportions that it seemed to dwarf men into mere nothingness. Up over its brow we climbed, nearly beaten down by the high mountain wind that roared with the voice of giants. And there we found them who waited for us. The Briton went down with a spear through him, reeled up, clutched him that wielded it and over the cliff they tumbled together, to fall for a thousand feet. A wild, short flurry of fury, a whirl of swords and the battle was over. Four tribesmen lay still at our feet, and one of the Romans crouched, seeking to stem the blood that leaped from the stump of a severed arm.

Over the cliff we shoved those we had slain, and we did up the Roman’s arm with leather strips, binding them tight, so that the arm ceased to bleed. Then once more we took up our way.

On, on; crags reeled above us; gorse slopes tilted crazily. The sun towered above the swaying peaks and sloped westward. Then as we crouched upon a crag, hidden by great boulders, a band of tribesmen passed beneath, walking upon a narrow trail that skirted precipices and wound around mountain shoulders. And as they passed beneath us, the Irishman gave a shout of wild joy, and bounding from the cliff, fell among them. With yells like wolves they rushed upon him, and his red hair gleamed above their black. The first to reach him went down with a cleft head, and the second screeched as his arm left his shoulder. With a wild battle-yell, he drove his sword through a hairy breast, plucked it forth and smote off a head. Then they swarmed over him like wolves over a lion, and an instant later his head went up on a spear. The face still seemed to wear the battle-joy.

They passed on, never suspecting our presence, and again we pressed on. Night fell and the moon rose, making the peaks rear up like vague ghosts, throwing strange shadows among the valleys. As we went we found signs of the march, and of the retreat. There a Roman lying at the foot of a precipice, a smashed heap, perhaps a long spear through him; there a headless body, there a bodyless head. Shattered helmets, broken swords told the mute tale of fiercely contested battles.

On through the night we staggered, halting only at dawn, when we hid ourselves among the boulders and ventured forth again only when night had fallen. Groups of tribesmen passed close, but we remained undiscovered, though at times we could have touched them as they went.

Dawn was breaking when we came upon a different land; a land that was merely a great plateau. Mountains towered on every hand, except to the south where the level land seemed to run for a long way. So I believed that we had left the mountains and had come upon the foot hills that stretched away to finally merge upon the fertile plains of the south.

So we came upon a lake and halted there. There was no sign of a foe, no smoke in the sky. But as we stood there, the Roman who had but one arm pitched forward on his face without a sound, and there was a throwing spear through him.

We scanned the lake. No boats rippled its surface. No foe showed among the scant reeds near its bank. We turned, gazing across the heather. And without a sound the second Roman crumpled and fell forward, a short spear standing between his shoulders.

Sword bared, and mazed, I searched the silent slopes for sign of a foe. The heath stretched bare from mountain to mountain, and nowhere was the heather tall enough to hide a man, not even a Caledonian. No ripple stirred the lake—what caused that reed to sway when the others were motionless? I bent forward, peering into the water. Beside the reed a bubble rose to the surface. I bent nearer, wondering—a bestial face leered up at me, just below the surface of the lake! An instant’s astoundment—then my frantic-swung sword split that hairy face, checking just in time the spear that leaped for my breast. The waters of the lake boiled in turmoil, and presently there floated to the surface the form of the savage, the sheaf of throwing spears still in his belt, his apelike hand still grasping the hollow reed through which he had breathed. Then I knew why so many Romans had been strangely slain by the shores of the lakes.

I flung away my shield, discarded all accouterments except my sword, dagger, and armor. A certain ferocious exultation thrilled me. I was one man, amid a savage land, amid a savage people who thirsted for my blood. By Thor and Woden, I would teach them how a Norseman passed! With each passing moment I became less of the cultured Roman. All dross of education and civilization slipped from me, leaving only the primitive man, only the primordial soul, red-taloned, ferocious.

And a slow, deep rage began to rise in me, coupled with a vast Nordic contempt for my foes. I was in good mood to go berserk. Thor knows I had had fighting in plenty along the march and along the retreat, but the fighting soul of the Norse was astir in me, that has mystic depths deeper than the North Sea. I was no Roman. I was a Norseman, a hairychested, yellow-bearded barbarian. And I strode the heath as arrogantly as if I trod the deck of my own galley. Picts—what were they? Stunted dwarfs whose day had passed. It was strange what a terrific hate began to consume me. And yet not so strange, for the further I receded in savagery, the more primitive my impulses became, and the fiercer flamed the intolerant hatred of the stranger, that first impulse of the primal tribesman. But there was a deeper, more sinister reason at the back of my mind, though I knew it not. For the Picts were men of another age, in very truth, the last of the Stone Age peoples, whom the Celts and Nordics had driven before them when they came down from the North. And somewhere in my mind lurked a nebulous memory of fierce, merciless warfare, waged in a darker age.

And there was a certain awe, too, not for their fighting qualities, but for the sorcery which all peoples firmly believed the Picts to possess. I had seen their cromlechs all over Britain, and I had seen the great rampart they had built not far from Corinium. I knew that the Celtic Druids hated them with a hate that was surprising, even in priests. Not even the Druids could, or would, tell just how the Stone Age men reared those immense barriers of stone, or for what reason, and the mind of the ordinary man fell back upon that explanation which has served for ages—witchcraft. More, the Picts themselves believed firmly that they were warlocks and perhaps that had something to do with it.

And I fell to wondering just why we five hundred men had been ordered out on that wild raid. Some had said to seize a certain Pictish priest, some that we sought word of the Pictish chief, one Bran Mak Morn. But none knew except the officer in command, and his head rode a Pictish spear somewhere out in that sea of mountain and heather. I wished that I could meet that same Bran Mak Morn. ’Twas said that he was unmatched in warfare, either with army or singly. But never had we seen a warrior who seemed so much in command as to justify the idea that he was the chief. For the savages fought like wolves, though with a certain rude discipline.

Perhaps I might meet him, and if he were as valiant as they said, he would surely face me.

I scorned concealment. Nay, more, I chanted a fierce song as I strode, beating time with my sword. Let the Picts come when they would. I was ready to die like a warrior.

I had covered many miles when I rounded a low hill and came full upon some hundred of them, fully armed. If they expected me to turn and flee, they were far in error. I strode to meet them, never altering my gait, never altering my song. One of them charged to meet me, head down, point on, and I met him with a down-smiting blow that cleft him from left shoulder to right hip. Another sprang in from the side, thrusting at my head, but I ducked so that the spear swished over my shoulder, and ripped out his guts as I straightened. Then they were surging all about me, and I cleared a space with one great two-handed swing and set my back close to the steep hillside, close enough to prevent them from running behind me, but not too close for me to swing my blade. If I wasted motion and strength in the up and down movement, I more than made up by the smashing power of my sword-blows. No need to strike twice, on any foe. A swart, bearded savage sprang in under my sword, crouching, stabbing upward. The sword blade turned on my corselet, and I stretched him senseless with a downward smash of the hilt. They ringed me like wolves, striving to reach me with their shorter swords, and two went down with cleft heads as they tried to close with me. Then one, reaching over the shoulders of the others, drove a spear through my thigh, and with a roar of fury I thrust savagely, spitting him like a rat. Before I could regain my balance, a sword gashed my right arm and another shattered upon my helmet. I staggered, swung wildly to clear a space, and a spear tore through my right shoulder. I swayed, went to the ground and reeled up again. With a terrific swing of my shoulders I hurled my clawing, stabbing foes clear, and then, feeling my strength oozing from me with my blood, gave one lionlike roar and leaped among them, clean berserk. Into the press I hurled myself, smiting left and right, depending only on my armor to guard me from the leaping blades. That battle is a crimson memory. I was down, up, down again, up, right arm hanging, sword flailing in left hand. A man’s head spun from his shoulders, an arm vanished at the elbow, and then I crumpled to the ground striving vainly to lift the sword that hung in my loose grasp.

A dozen spears were at my breast in an instant, when someone threw the warriors back, and a voice spoke, as of a chief:

“Stay! This man must be spared.”

Vaguely as through a fog, I saw a lean, dark face as I reeled up to face the man who spoke.

I saw a slim, dark-haired man, whose head would come scarcely to my shoulder, but who seemed as lithe and strong as a leopard. He was scantily clad in plain, close-fitting garments, his only arm a long straight sword. He resembled in form and features the Picts no more than did I, yet there was about him a certain apparent kinship to them.

All those things I noted vaguely, scarce able to keep my feet.

“I have seen you,” I said, speaking as one mazed. “Often and often in the forefront of battle I have seen you. Always you led the Picts to the charge while your chiefs slunk far from the field. Who are you?”

Then the warriors and the world and the sky faded, and I crumpled to the heath.

Faintly I heard the strange warrior say,

“Staunch his wounds and give him food and drink.” I had learned their language from Picts who came to trade at the Wall.

I was aware that they did as the warrior bid them, and presently I came to my senses, having drunk much of the wine that the Picts brew from heather. Then, spent, I lay upon the heather and slept, nor recked of all the savages in the world.

When I awoke the moon was high in the sky. My arms were gone and my helmet, and several armed Picts stood guard over me. When they saw I was awake they motioned me to follow them, and set out across the heath. Presently we came to a high bare hill with a fire gleaming upon its top. On a boulder beside the fire sat the strange dark chief, and about him, like spirits of the Dark World, sat Pictish warriors in a silent ring.

They led me before the chief, if such he was, and I stood there, gazing at him without defiance or fear. And I sensed that here was a man different from any I had ever seen. I was aware of a certain force, a certain unseen power radiating from the man, that seemed to set him apart from common men. It was as though from the heights of self-conquest he looked down upon men, brooding, inscrutable, fraught with the ages’ knowledge, somber with the ages’ wisdom. Chin in hand, he sat, dark, unfathomed eyes fixed upon me.

“Who are you?”

“A Roman citizen.”

“A Roman soldier. One of the wolves who have torn the world for far too many centuries.”

Among the warriors passed a murmur, fleeting as the whisper of the night wind, sinister as the flash of a wolf’s fang.

“There be those whom my people hate more than they do the Romans,” said he. “But you are a Roman, to be sure. And yet, methinks they must grow taller Romans than I had thought. And your beard, what turned it yellow?”

At the sardonic tone, I threw back my head, and though my skin crawled at the thought of the swords at my back, I answered proudly.

“By birth I am a Norseman.”

A savage, blood-lusting yell went up from the crouching horde, and in an instant they surged forward. A single motion of the chief’s hand sent them slinking back, eyes blazing. His own eyes had never left my face.

“My tribe are fools,” said he. “For they hate the Norse even more than they do the Romans. For the Norse harry our shores incessantly; but it is Rome that they should hate.”

“But you are no Pict!”

“I am a Mediterranean.”

“Of Caledonia?”

“Of the world.”

“Who are you?”

“Bran Mak Morn.”

“What!” I had expected a monstrosity, a hideous, deformed giant, a ferocious dwarf built in keeping with the rest of his race. “You are not as these.”

“I am as the race was,” he replied. “The line of chiefs has kept its blood pure through the ages, scouring the world for women of the Old Race.”

“Why does your race hate all men?” I asked curiously. “Your ferocity is a byword among the nations.”

“Why should we not hate?” his dark eyes lit with a sudden fierce glitter. “Trampled upon by every wandering tribe, driven from our fertile lands, forced into the waste places of the world, deformed in body and in mind. Look upon me. I am what the race once was. Look about you. A race of ape-men, we that were the highest type of men the world could boast.”

I shuddered in spite of myself at the hate that vibrated in his deep, resonant voice.

Between the lines of warriors came a girl, who sought the chief’s side and nestled close to him. A slim, shy little beauty, not much more than a child. Mak Morn’s face softened somewhat as he put his arm about her slender body. Then the brooding look returned to his dark eyes.

“My sister, Norseman,” he said. “I am told that a rich merchant of Corinium has offered a thousand pieces of gold to any who brings her to him.”

My hair prickled for I seemed to sense a sinister minor note in the Caledonian’s even voice. The moon sank below the western horizon, touching the heather with a red tinge, so that the heath looked like a sea of gore in the eery light.

The chief’s voice broke the stillness. “The merchant sent a spy past the Wall. I sent him his head.”

I started. A man stood before me. I had not seen him come. A very old man he was, clad only in a loincloth. A long white beard fell to his waist, and he was tattooed from crown to heel. His leathery face was creased with a million wrinkles, his hide was scaly as a snake’s. From beneath sparse white brows his great strange eyes blazed, as though seeing weird visions. The warriors stirred restlessly. The girl shrank back into Mak Morn’s arms as if frightened.

“The god of War rides the night wind,” spoke the wizard suddenly, in a high eery voice. “The kites scent blood. Strange feet tramp the roads of Alba. Strange oars beat the Northern Sea.”

“Lend us your craft, wizard,” commanded Mak Morn imperiously.

“You have displeased the old gods, Chief,” the other answered. “The temples of the Serpent are deserted. The white god of the moon feasts no more on man flesh. The lords of the air look down from their ramparts and are not pleased. Hai, hai! They say a chief has turned from the path.”

“Enough,” Mak Morn’s voice was harsh. “The power of the Serpent is broken. The neophytes offer up no more humans to their dark divinities. If I lift the Pictish nation out of the darkness of the valley of abysmal savagery, I brook no opposition by prince or priest. Mark my words, wizard.”

The old man raised great eyes, weirdly alit, and stared into my face.

“I see a yellow-haired savage,” came his fleshcrawling whisper. “I see a strong body and a strong mind, such as a chief might feast upon.”

An impatient ejaculation from Mak Morn.

The girl put her arms about him timidly and whispered in his ear.

“Some characteristics of humanity and kindliness remain still with the Picts,” said he, and I sensed the fierce self-mockery in his tone. “The child asks me that you go free.”

Though he spoke in the Celtic language, the warriors understood, and muttered discontentedly.

“No!” exclaimed the wizard violently.

The opposition steeled the chief’s resolution. He rose to his feet.

“I say the Norseman goes free at dawn.”

A disapproving silence answered him.

“Dare any of ye to step upon the heath and match steel with me?” he challenged.

The wizard spoke. “Hark ye, Chief. I have outlived a hundred years. I have seen chiefs and conquerors come and go. In midnight forests have I battled the magic of the Druids. Long have ye mocked my power, man of the Old Race, and here I defy ye. I bid ye unto the combat.”

No word was spoken. The two men advanced into the firelight which threw its fitful gleam into the shadows.

“If I conquer, the Serpent coils again, the Wildcat screeches again, and thou art my slave forever. If thou dost conquer, my arts are thine and I will serve thee.”

Wizard and chief faced each other. The lurid flame-flares lit their faces. Their eyes met, clashed. Yes, the combat between the eyes and the souls behind them was as clearly evident as though they had been battling with swords. The wizard’s eyes widened, the chief’s narrowed. Terrific forces seemed to emanate from each; unseen powers in combat swirled about them. And I was vaguely aware that it was but another phase of the eon-old warfare. The battle between Old and New. Behind the wizard lurked thousands of years of dark secrets, sinister mysteries, frightful nebulous shapes, monsters half hidden in the fogs of antiquity. Behind the chief, the clear strong light of the coming Day, the first kindling of civilization, the clean strength of a new man with a new and mighty mission. The wizard was the Stone Age typified; the chief, the coming civilization. The destiny of the Pictish race, perhaps, hinged on that struggle.

Both men seemed in the grasp of terrific effort. The veins stood out upon the chief’s forehead. The eyes of both blazed and glittered. Then a gasp broke from the wizard. With a shriek he caught at his eyes, and slumped to the heather like an empty sack.

“Enough!” he gasped. “You conquer, Chief.” He rose, shaken, submissive.

The tense, crouching lines relaxed, sat in their places, eyes fixed on the chief. Mak Morn shook his head as if to clear it. He stepped to the boulder and sat down, and the girl threw her arms about him, murmuring to him in a gentle, joyous voice.

“The Sword of the Picts is swift,” mumbled the wizard. “The Arm of the Pict is strong. Hai! They say a mighty one has risen among the Western Men. Gaze ye upon the ancient Fire of the Lost Race, Wolf of the Heather! Hai, hai! They say a chief has risen to lead the race onward.”

The wizard stooped above the coals of the fire which had gone out, muttering to himself.

Stirring the coals, mumbling in his white beard, he half droned, half sang, a weird chant, of little meaning or rhyme, but with a kind of wild rhythm, remarkably strange and eery.

“O’er lakes agleam the old gods dream;

Ghosts stride the heather dim.

The night’s winds croon; the eery moon

Slips o’er the ocean’s rim.

From peak to peak the witches shriek.

The gray wolf seeks the height.

Like gold sword-sheath, far o’er the heath

Glimmers the wandering light.”

The ancient stirred the coals, pausing now and then to toss on them some weird object, keeping time with his motions with his chant.

“Gods of heather, gods of lake,

Bestial fiends of swamp and brake;

White god riding on the moon,

Jackal jawed, with voice of loon;

Serpent god whose scaly coils

Grasp the Universe in toils.

See, the Unseen Sages sit;

See the council fires alit.

See I stir the glowing coals,

Toss on manes of seven foals.

Seven foals all golden shod

From the herds of Alba’s god.

Now in numbers one and six,

Shape and place the magic sticks.

Scented wood brought from afar,

From the land of Morning Star.

Hewn from limbs of sandal-trees,

Brought far o’er the EasternSeas.

Sea-snake’s fangs, see now, I fling,

Pinions of a sea-gull’s wing.

Now the magic dust I toss,

Men are shadows, life is dross.

Now the flames crawl, ere they blaze,

Now the smokes rise in a haze.

Fanned by far off ocean blast

Leaps the tale of distant past.”

In and out among the coals licked the thin red flames, now leaping in swift upward spurts, now vanishing, now catching the tinder thrown upon it, with a dry crackle that sounded through the stillness. Wisps of smoke began to curl upward in a mingling, hazy cloud.

“Dimly, dimly glimmers the starlight,

Over the heather-hill, over the vale.

Gods of the Old Land brood o’er the far night,

Things of the Darkness ride on the gale.

Now while the fire smoulders, while smokes enfold it,

Now ere it leaps into clear, mystic flame,

Harken once more (else the dark gods withhold it),

Hark to the tale of the race without name.”

The smoke floated upward, swirling about the wizard; as through a dense fog his fierce yellow eyes peered. As if across far spaces his voice came floating, with a strange impression of disembodiment. With a weird intonation as though the voice were, not the voice of the ancient, but a something detached, a something apart; as if disembodied ages, and not the wizard’s mind, spake through him.

A wilder setting I have seldom seen. Overhead all darkness, scarce a star aglitter, the waving tentacles of the Northern Lights reaching lurid banners across the sullen sky; somber slopes stretching away to mingle with vagueness, a dim sea of silent, waving heather; and on that bare, lone hill, the half-human horde crouching like somber specters of another world, their bestial faces now merging in the shadows, now touched with blood as the firelight veered and flickered. And Bran Mak Morn sitting like a statue of bronze, his face thrown into bold relief by the light of the leaping flames. And that weird face, limned by the eery light, with its great, blazing yellow eyes, and its long snow-white beard.

“A mighty race, the men of the Mediterranean.”

Savage faces alit, they leaned forward. And I found myself thinking the wizard was right. No man might civilize those primeval savages. They were untamable, unconquerable. The spirit of the wild, of the Stone Age was theirs.

“Older than the snow-crowned peaks of Caledon.”

The warriors leaned forward, evincing eagerness and anticipation. I sensed that the tale ever intrigued them, though doubtless they had heard it a hundred times from a hundred chiefs and ancients.

“Norseman,” suddenly breaking the train of his discourse, “what lies beyond the Western Channel?”

“Why, the isle of Hibernia .”

“And beyond?”

“The isles that the Celts call Aran.”

“And beyond?”

“Why, in sooth, I know not. Human knowledge pauses there. No ship has sailed those seas. The learned men call it Thule. The Unknown, the realm of illusion, the edge of the world.”

“Hai, hai! That mighty western ocean washes the shores of continents unknown, islands unguessed.

“Far, far across the great, wave-tossed vastness of the Atlantic lie two great continents, so vast that the smaller would dwarf all Europe. Twin lands of immense antiquity; lands of ancient, crumbling civilization. Lands in which roamed tribes of men wise in all craftsmanship, while this land ye call Europe was yet a vast, reptile-haunted swamp, a dank forest known but to apes.

“So mighty are these continents that they span the world, from the snows of the north to the snows of the south. And beyond them lies a great ocean, the Sea of Silent Waters (the Pacific Ocean). Many islands are upon that sea, and those islands were once the mountain peaks of a great land—the lost land of Lemuria.

“And the continents are twin continents, joined by a narrow neck of land. The western coast of that northern continent is fierce and rugged. Huge mountains rear skyward. But those peaks were islands upon a time, and to those islands came the Nameless Tribe, wandering down from the north, so many thousand years ago that a man would grow aweary numbering them. A thousand miles to the north and west had the tribe come into being, there upon the broad and fertile plains close by the northern channels, which divide the continent of the north from Asia.”

“Asia!” I exclaimed, bewildered.

The ancient jerked up his head angrily, eyeing me savagely. Then he continued.

“There, in the dim haze of unnamed past, had the tribe won up from crawling sea-thing to ape and from ape to ape-man and from ape-man to savage.

“Savages they were still when they came down the coast, fierce and warlike.

“Skilled in the chase they were, for they had lived by the hunt for untold centuries. Strong built men they were, not tall nor huge, but lean and muscular like leopards, swift and mighty. No nation might stand before them. And they were the first Men.

“Still they clad themselves in the hides of beasts, and their stone implements were crudely chipped. Upon the western islands they took their abode, the islands that lay laughing in a sunny sea. And there they had their habitation for thousands and thousands of years. For centuries upon the western coast. The isles of the west were wondrous isles, lapped in sunlit seas, rich and fertile. There the tribe laid aside the arms of war and taught themselves the arts of peace. There they learned to polish their implements of stone. There they learned to raise grain and fruits, to cultivate the soil; and they were content, and the harvest gods laughed. And they learned to spin and to weave and to build them huts. And they became skilled in the working of pelts and in the making of pottery.

“Far to the west, across the roaming waves, lay the vast, dim land of Lemuria. And anon came fleets of canoes bearing strange raiders, the half-human Men of the Sea. Perhaps from some strange seamonster had those sprang, for they were scaly like unto a shark, and they could swim for hours under the water. Ever the tribe beat them back, but often they came, for renegades of the tribe fled to Lemuria. To the east and the south great forests stretched away to the horizons, peopled by ferocious beasts and ape-men.

“So the centuries glided by on the wings of Time. Stronger and stronger grew the Nameless Tribe, more skillful in craftsmanship; less skilled in war and the chase. And slowly the Lemurians fared on the upward climb.

“Then, upon a day, a mighty earthquake rocked the world. Sky mingled with sea and the land reeled between. With the thunder of gods at war, the islands of the west plunged upward and lifted from the sea. And lo, there were mountains upon the new formed western coast of the northern continent. And lo, the land of Lemuria sank beneath the waves, leaving only a great mountainous island, surrounded by many isles which had been her highest peaks.

“And upon the western coast, mighty volcanoes roared and bellowed and their flaming spate rushed down the coast and swept away all traces of the civilization that was being conceived. From a fertile vineyard the land became a desert.

“Eastward fled the tribe, driving the ape-men before them, until they came upon broad and rich plains far to the east. There they abode for centuries. Then the great ice fields came down from the Arctics, and the tribe fled before them. Then followed a thousand years of wandering.

“Down into the southern continent they fled, ever driving the beast-men (Neanderthals) before them. And finally, in a great war, they drove them forth entirely. Those fled far to the south and, by means of the marshy islands that then spanned the sea, crossed into Africa , thence wandering up into Europe, where there were then no men except apemen.

“Then the Lemurians, the Second Race, came into the northern land. Far up the scale of life had they made their way, and they were a swart, strange race; short, broad men were they, with strange eyes like unto unknown seas. Little they knew of cultivation or of craft, but they possessed strange knowledge of curious architecture and from the Nameless Tribe had they learned to make implements of polished obsidian and jade and argillite.

“And ever the great ice fields pushed south and ever the Nameless Tribe wandered before it. No ice came into the southern continent, nor even near it, but it was a dank, swampy land, serpent-haunted. So they made them boats and sailed to the sea-girt land of Atlantis. Now the Atlanteans (Cro-Magnons) were the Third Race. They were physical giants, finely made men, who inhabited caves and lived by the chase. They had no skill in artisanship, but were artists. When they were not hunting or warring among themselves, they spent their time in painting and drawing pictures of men and beasts upon the walls of their caverns. But they could not match the Nameless Tribe in craft, and they were driven forth. They, too, made their way to Europe, and there waged savage warfare with the beast-men who had gone before them.

“Then there was war among the tribes, and the conquerors drove forth the conquered. And among those was a very wise, very ancient wizard; and he put a curse upon the land of Atlantis, that it should be unknown to the tribes of men. No boat from Atlantis should ever gain another shore, no foreign sail should ever sight the broad beaches of Atlantis. Girt by unsailed seas should the land lie unknown until ships with the heads of serpents should come down from the northern seas, and four hosts should battle on the Isle of Sea-fogs, and a great chief should rise among the people of the NamelessTribe.

“So those crossed to Africa, rowing from island to island, and went up the coast until they came to the Middle Sea (Mediterranean) which lay enjeweled amid sunny shores.

“There did the tribe abide for centuries, and grew strong and mighty, and from thence did they spread all over the world. From the Afric deserts to the Baltic forests, from the Nile to the peaks of Alba they ranged, growing their grain, grazing their cattle, weaving their cloth. They built their crannogs in the Alpan lakes; they reared their temples of stone upon the plains of Britain. They drove the Atlanteans before them, and they smote the red-haired reindeer men.

“Then from the North came the Celts, bearing sword and spears of bronze. From the dim lands of Mighty Snows they came, from the shores of the far North Sea. And they were the Fourth Race. The Picts fled before them. For they were mighty men, tall and strong, lean-built and gray-eyed, with tawny hair. All over the world Celt and Pict battled, and ever the Celt conquered. For in the long ages of peace, the tribes had forgotten the arts of war. To the waste places of the world they fled.

“And so fled the Picts of Alba; to the west and to the north and there they mingled with the red-haired giants which they had driven from the plains in ages gone by. Such is not the way of the Pict, but shall tradition serve a nation whose back is at the wall?

“And so as the ages passed, the race changed. The slim, small black-haired people, mingling with the huge, coarse-featured, red-haired savages, formed a strange, distorted race; twisted in soul as in body. And they grew fierce and cunning in warfare; but forgotten the old arts. Forgotten the loom and the kiln and the mill. But the line of chiefs remained untainted. And such art thou, Bran Mak Morn, Wolf of the Heather.”

For a moment there was silence; the silent ring still harkening dreamily, as if to the echo of the wizard’s voice.The night wind whispered by. The fire caught the tinder and burst suddenly into vivid flame, flinging lean red arms to catch the shadows.

The wizard’s voice took up its drone.

“The glory of the Nameless Tribe is vanished; like the snow that falls on the sea; like the smoke that rises in the air. Mingling with past eternities. Vanished the glory of Atlantis; fading the dark empire of the Lemurians. The people of the Stone Age are melting like hoarfrost before the sun. Out of the night we came; into the night we go. All are shadows. A shadow race are we. Our day is past. Wolves roam the temples of the Moon-God. Water serpents coil amid our sunken cities. Silence broods over Lemuria; a curse haunts Atlantis. Red-skinned savages roam the western lands, wandering o’er the valley of the Western River, befouling the entempled ramparts which the men of Lemuria reared in worship of the God of the Sea. And to the south, the empire of the Toltecs of Lemuria is crumbling. So the First Races are passing. And the Men of the New Dawn grow mighty.”

The ancient took a flaming brand from the fire and with a motion incredibly swift, inscribed the circle and triangle in the air. And strangely, the mystic symbol seemed to hover in the air for a moment, a ring of fire.

“The circle without beginning,” droned the wizard. “The circle unending. The Snake with its tail in its mouth, that encompasses the Universe. And the Mystic Three. Beginning, passivity, ending. Creation, preservation, destruction. Destruction, preservation, creation. The Frog, the Egg, and the Serpent. The Serpent, the Egg, and the Frog. And the Elements: Fire, Air, and Water. And the phallic symbol. The Fire-God laughs.”

I was aware of the fierce, almost ferocious intensity with which the Picts stared into the fire. The flames leaped and blazed. Smoke billowed up and vanished, and a strange yellow haze took its place, that was neither fire, smoke, nor fog, and yet seemed a blending of all three. World and sky seemed to merge with the flames. I became, not a man, but a pair of disembodied Eyes.

Then somewhere in the yellow fog vague pictures began to show, looming and vanishing. I sensed that the past was gliding by in a dim panorama. There was a battle-field and on one side were many men such as Bran Mak Morn, but unlike him in that they seemed unused to fray. On the other side was a horde of tall gaunt men, armed with sword and spears of bronze. The Gaels!

Then on another field another battle was in progress, and I sensed that hundreds of years had passed. Again the Gaels charged to battle with their arms of bronze, but this time it was they who reeled back in defeat, before a host of huge, yellow-haired warriors, armed also with bronze. The battle marked the coming of the Brythons, who gave their name to the isle of Britain.

Then a serried line of vague and fleeting scenes, which passed too rapidly to be distinguished. They gave the impression of great deeds, mighty happenings; but only dim shadows showed. For an instant a dim face loomed. A strong face, with steel-gray eyes, and yellow mustaches drooping over thin lips. I sensed that it was that other Bran, the Celtic Brennus whose Gallic hordes had sacked Rome. Then in its place another face stood out with startling boldness. The face of a young man, haughty, arrogant, with a magnificent brow, but with lines of sensual cruelty about his mouth. The face of both a demigod and a degenerate.

Caesar!

A shadowy beach. A dim forest; the crash of battle. The legions shattering the hordes of Caractacus.

Then vaguely, swiftly, passed shadows of the pomp and glory of Rome. There were her legions returning in triumph, driving before them hundreds of chained captives. There were shown the corpulent senators and nobles at their luxurious baths and their banquets and their debauches. There were shown the effeminate, slothful merchants and nobles lolling in lustful ease in Ostia, in Massilia, in Aqua Sulae. Then in abrupt contrast, the gathering hordes of the outer world. The fierce-eyed, yellow-bearded Norsemen; the huge-bodied Germanic tribes; the wild, flame-haired savages of Wales and Damnonia, and their allies, the Pictish Silures. The past had faded; present and future took its place!

Then a vague holocaust, in which nations moved and armies and men faded and shifted. “Rome falls!” suddenly the wizard’s fiercely exultant voice broke the silence. “The Vandal’s foot spurs the Forum. A savage horde marches along the Via Appia. Yellow-haired raiders violate the Vestal Virgins. And Rome falls!”

A ferocious yell of triumph went winging up into the night.

“I see Britain beneath the heel of the Norse invaders. I see the Picts trooping down from the mountains. There is rapine, fire, and warfare.”

In the fire-fog leaped the face of Bran Mak Morn.

“Hale the uplifter! I see the Pictish nation striding upward toward the new light!

Wolf on the height

Mocking the night;

Slow comes the light

Of a nation’s new dawn.

Shadow hordes massed

Out of the past.

Fame that shall last

Strides on and on.

Over the vale

Thunders the gale

Bearing the tale

Of a nation up-lifted.

Flee, wolf and kite!

Fame that is bright.”

From the east came stealing a dim gray radiance. In the ghostly light Bran Mak Morn’s face showed bronze once more, expressionless, immobile; dark eyes gazing unwaveringly into the fire, seeing there his mighty ambitions, his dreams of empire fading into smoke.

“For what we could not keep by battle, we have held by cunning for years and centuries unnumbered. But the New Races rise like a great tidal wave and the Old gives place. In the dim mountain of Galloway shall the nation make its last fierce stand. And as Bran Mak Morn falls, so vanished the Lost Fire—forever. From the centuries, from the eons.”

And as he spoke, the fire gathered itself into one great flame that leaped high in the air, and in mid-air vanished.

And over the far eastern mountains floated the dim dawn.