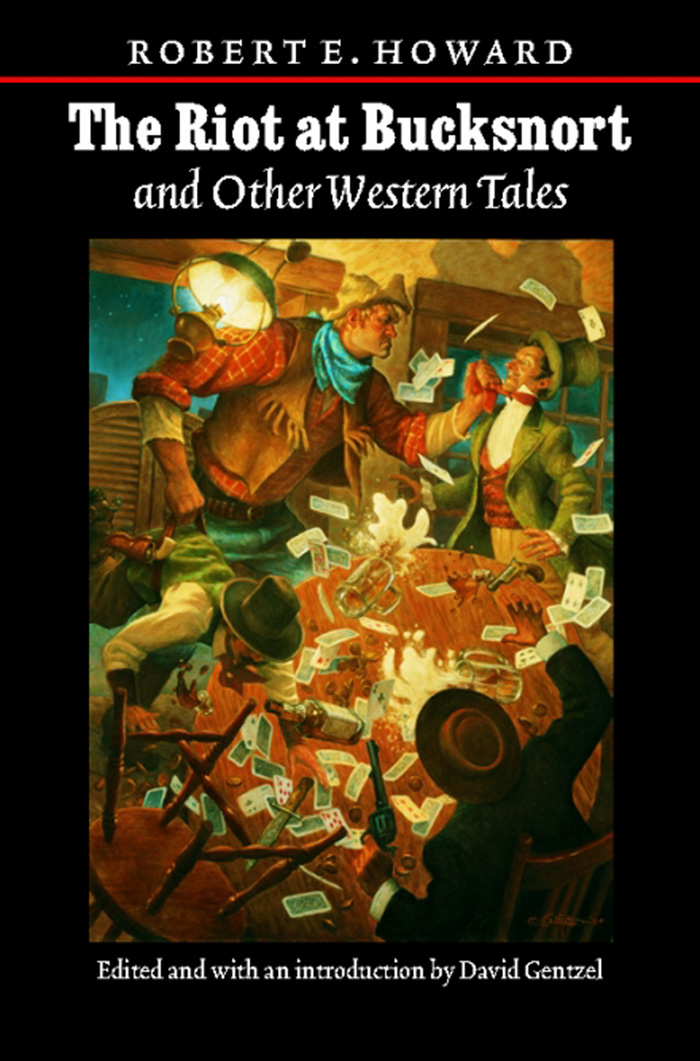

Cover from the collection The Riot at Bucksnort and Other Western Tales (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The Summit County Journal, July-October 1968.

However, this version is the chapter broken out of A Gent from Bear Creek as published by Grant, 1965 (“Photographic reprint of the

Jenkins first edition.” [1937]), though here taken from the 2005 collection The Riot at Bucksnort and Other Western Tales.

I didn’t pull up Alexander till I was plumb out of sight of Tomahawk. Then I slowed down and taken stock of myself, and my spirits was right down in my spiked shoes which still had some of Mister O’Tool’s hide stuck onto the spikes. Here I’d started forth into the world to show Glory McGraw what a he-bearcat I was, and now look at me. Here I was without even no clothes but them derned spiked shoes which pinched my feet, and a pair of britches some cowpuncher had wore the seat out of and patched with buckskin. I still had my gunbelt and the dollar Pap gimme, but no place to spend it. I likewise had a goodly amount of lead under my hide.

“By golly!” I says, shaking my fists at the universe at large. “I ain’t goin’ to go back to Bear Creek like this and have Glory McGraw laughin’ at me! I’ll head for the Wild River settlements and git me a job punchin’ cows till I got money enough to buy me store-bought boots and a hoss!”

I then pulled out my bowie knife which was in a scabbard on my gunbelt, and started digging the slug out of my hip and the buckshot out of my back. Them buckshot was kinda hard to get to, but I done it. I hadn’t never held a job of punching cows, but I’d had plenty experience roping wild bulls up in the Humbolts. Them bulls wanders off the lower ranges into the mountains and grows most amazing big and mean. Me and Alexander had had plenty experience with them, and I had me a lariat which would hold any steer that ever bellered. It was still tied to my saddle, and I was glad none of them cowpunchers hadn’t stole it. Maybe they didn’t know it was a lariat. I’d made it myself, especial, and used it to rope them bulls and also cougars and grizzlies which infests the Humbolts. It was made out of buffalo hide, ninety foot long and half again as thick and heavy as the average lariat, and the honda was a half-pound chunk of iron beat into shape with a sledge hammer. I reckoned I was qualified for a vaquero even if I didn’t have no cowboy clothes and was riding a mule.

So I headed acrost the mountains for the cow country. They warn’t no trail the way I taken, but I knowed the direction Wild River lay in, and that was enough for me. I knowed if I kept going that way I’d hit it after a while. Meanwhile, they was plenty of grass in the draws and along the creeks to keep Alexander fat and sleek, and plenty of squirrels and rabbits for me to knock over with rocks. I camped that night away up in the high ranges and cooked me nine or ten squirrels over a fire and et ’em, and while that warn’t much of a supper for a appertite like mine, still I figgered next day I’d stumble on to a b’ar or maybe a steer which had wandered offa the ranges.

Next morning before sunup I was on Alexander and moving on, without no breakfast, because it looked like they warn’t no rabbits nor nothing near abouts, and I rode all morning without sighting nothing. It was a high range, and nothing alive there but a buzzard I seen onst, but late in the afternoon I crossed a backbone and come down into a whopping big plateau about the size of a county, with springs and streams and grass growing stirrup-high along ’em, and clumps of cottonwood, and spruce, and pine thick up on the hillsides. They was canyons and cliffs, and mountains along the rim, and altogether it was as fine a country as I ever seen, but it didn’t look like nobody lived there, and for all I know I was the first white man that ever come into it. But they was more soon, as I’ll relate.

Well, I noticed something funny as I come down the ridge that separated the bare hills from the plateau. First I met a wildcat. He come lipping along at a right smart clip, and he didn’t stop. He just gimme a wicked look sidewise and kept right on up the slope. Next thing I met a lobo wolf, and after that I counted nine more wolves, and they was all heading west, up the slopes. Then Alexander give a snort and started trembling, and a cougar slid out of a blackjack thicket and snarled at us over his shoulder as he went past at a long lope. All them varmints was heading for the dry bare country I’d just left, and I wondered why they was leaving a good range like this one to go into that dern no-account country.

It worried Alexander too, because he smelt of the air and brayed kind of plaintively. I pulled him up and smelt the air too, because critters run like that before a forest fire, but I couldn’t smell no smoke, nor see none. So I rode on down the slopes and started across the flats, and as I went I seen more bobcats, and wolves, and painters, and they was all heading west, and they warn’t lingering none, neither. They warn’t no doubt that them critters was pulling their freight because they was scairt of something, and it warn’t humans, because they didn’t ’pear to be scairt of me a mite. They just swerved around me and kept trailing. After I’d gone a few miles I met a herd of wild hosses, with the stallion herding ’em. He was a big mean-looking cuss, but he looked scairt as bad as any of the critters I’d saw.

The sun was getting low, and I was getting awful hungry as I come into a open spot with a creek on one side running through clumps of willers and cottonwoods, and on the other side I could see some big cliffs looming up over the tops of the trees. And whilst I was hesitating, wondering if I ought to keep looking for eatable critters, or try to worry along on a wildcat or a wolf, a big grizzly come lumbering out of a clump of spruces and headed west. When he seen me and Alexander he stopped and snarled like he was mad about something, and then the first thing I knowed he was charging us. So I pulled my .44 and shot him through the head, and got off and onsaddled Alexander and turnt him loose in grass stirrup-high, and skun the b’ar. Then I cut me off some steaks and started a fire and begun reducing my appertite. That warn’t no small job, because I hadn’t had nothing to eat since the night before.

Well, while I was eating I heard hosses and looked up and seen six men riding toward me from the east. One was as big as me, but the other ones warn’t but about six foot tall apiece. They was cowpunchers, by their look, and the biggest man was dressed plumb as elegant as Mister Wilkinson was, only his shirt was jest only one color. But he had on fancy boots and a white Stetson and a ivory-butted Colt, and what looked like the butt of a sawed-off shotgun jutted out of his saddle scabbard. He was dark and had awful mean eyes, and a jaw which it looked like he could bite the spokes out of a wagon wheel if he wanted to.

He started talking to me in Piute, but before I could say anything, one of the others said: “Aw, that ain’t no Injun, Donovan, his eyes ain’t the right color.”

“I see that, now,” says Donovan. “But I shore thought he was a Injun when I first rode up and seen them old ragged britches and his sunburnt hide. Who the devil air you?”

“I’m Breckinridge Elkins, from Bear Creek,” I says, awed by his magnificence.

“Well,” says he, “I’m Wild Bill Donovan, which name is heard with fear and tremblin’ from Powder River to the Rio Grande. Just now I’m lookin’ for a wild stallion. Have you seen sech?”

“I seen a bay stallion headin’ west with his herd,” I said.

“ ’Twarn’t him,” says Donovan. “This here one’s a pinto, the biggest, meanest hoss in the world. He come down from the Humbolts when he was a colt, but he’s roamed the West from Border to Border. He’s so mean he ain’t never got him a herd of his own. He takes mares away from other stallions, and then drifts on alone just for pure cussedness. When he comes into a country all other varmints takes to the tall timber.”

“You mean the wolves and painters and b’ars I seen headin’ for the high ridges was runnin’ away from this here stallion?” I says.

“Exactly,” says Donovan. “He crossed the eastern ridge sometime durin’ the night, and the critters that was wise hightailed it. We warn’t far behind him; we come over the ridge a few hours ago, but we lost his trail somewhere on this side.”

“You chasin’ him?” I ast.

“Ha!” snarled Donovan with a kind of vicious laugh. “The man don’t live what can chase Cap’n Kidd! We’re just follerin’ him. We been follerin’ him for five hundred miles, keepin’ outa sight, and hopin’ to catch him off guard or somethin’. We got to have some kind of a big advantage before we closes in, or even shows ourselves. We’re right fond of life! That devil has kilt more men than any other ten hosses on this continent.”

“What you call him?” I says.

“Cap’n Kidd,” says Donovan. “Cap’n Kidd was a big pirate long time ago. This here hoss is like him in lots of ways, particularly in regard to morals. But I’ll git him, if I have to foller him to the Gulf and back. Wild Bill Donovan always gits what he wants, be it money, woman, or hoss! Now lissen here, you range-country hobo: we’re a-siftin’ north from here, to see if we cain’t pick up Cap’n Kidd’s sign. If you see a pinto stallion bigger’n you ever dreamed a hoss could be, or come onto his tracks, you drop whatever yo’re doin’ and pull out and look for us, and tell me about it. You keep lookin’ till you find us, too. If you don’t, you’ll regret it, you hear me?”

“Yessir,” I said. “Did you gents come through the Wild River country?”

“Maybe we did and maybe we didn’t,” he says with haughty grandeur. “What business is that of yore’n, I’d like to know?”

“Not any,” I says. “But I was aimin’ to go there and see if I could git me a job punchin’ cows.”

At that he throwed back his head and laughed long and loud, and all the other fellers laughed too, and I was embarrassed.

“You git a job punchin’ cows?” roared Donovan. “With them britches and shoes, and not even no shirt, and that there ignorant-lookin’ mule I see gobblin’ grass over by the creek? Haw! haw! haw! haw! You better stay up here in the mountains whar you belong and live on roots and nuts and jackrabbits like the other Piutes, red or white! Any self-respectin’ rancher would take a shotgun to you if you was to ast him for a job. Haw! haw! haw!” he says, and rode off still laughing.

I was that embarrassed I bust out into a sweat. Alexander was a good mule, but he did look kind of funny in the face. But he was the only critter I’d ever found which could carry my weight very many miles without giving plumb out. He was awful strong and tough, even if he was kind of dumb and potbellied. I begun to get kind of mad, but Donovan and his men was already gone, and the stars was beginning to blink out. So I cooked me some more b’ar steaks and et ’em, and the land sounded awful still, not a wolf howling nor a cougar squalling. They was all west of the ridge. This critter Cap’n Kidd sure had the country to hisself, as far as the meat-eating critters was consarned.

I hobbled Alexander close by and fixed me a bed with some boughs and his saddle blanket, and went to sleep. I was woke up shortly after midnight by Alexander trying to get in bed with me.

I sot up in irritation and prepared to bust him in the snoot, when I heard what had scairt him. I never heard such a noise. My hair stood straight up. It was a stallion neighing, but I never heard no hoss critter neigh like that. I bet you could of heard it for fifteen miles. It sounded like a combination of a wild hoss neighing, a rip saw going through a oak log full of knots, and a hungry cougar screeching. I thought it come from somewhere within a mile of the camp, but I warn’t sure. Alexander was shivering and whimpering he was that scairt, and stepping all over me as he tried to huddle down amongst the branches and hide his head under my shoulder. I shoved him away, but he insisted on staying as close to me as he could, and when I woke up again next morning he was sleeping with his head on my belly.

But he must of forgot about the neigh he heard, or thought it was jest a bad dream or something, because as soon as I taken the hobbles off of him he started cropping grass and wandered off amongst the thickets in his pudding-head way.

I cooked me some more b’ar steaks, and wondered if I ought to go and try to find Mister Donovan and tell him about hearing the stallion neigh, but I figgered he’d heard it. Anybody that was within a day’s ride ought to of heard it. Anyway, I seen no reason why I should run errands for Donovan.

I hadn’t got through eating when I heard Alexander give a horrified bray, and he come lickety-split out of a grove of trees and made for the camp, and behind him come the biggest hoss I ever seen in my life. Alexander looked like a potbellied bull pup beside of him. He was painted—black and white—and he r’ared up with his long mane flying agen the sunrise, and give a scornful neigh that nigh busted my eardrums, and turned around and sa’ntered back toward the grove, cropping grass as he went, like he thunk so little of Alexander he wouldn’t even bother to chase him.

Alexander come blundering into camp, blubbering and hollering, and run over the fire and scattered it every which a way, and then tripped hisself over the saddle which was laying near by, and fell on his neck braying like he figgered his life was in danger.

I catched him and throwed the saddle and bridle on to him, and by that time Cap’n Kidd was out of sight on the other side of the thicket. I onwound my lariat and headed in that direction. I figgered not even Cap’n Kidd could break that lariat. Alexander didn’t want to go; he sot back on his haunches and brayed fit to deefen you, but I spoke to him sternly, and it seemed to convince him that he better face the stallion than me, so he moved out, kind of reluctantly.

We went past the grove and seen Cap’n Kid cropping grass in the patch of rolling prairie just beyond, so I rode toward him, swinging my lariat. He looked up and snorted kinda threateningly, and he had the meanest eye I ever seen in man or beast; but he didn’t move, just stood there looking contemptuous, so I throwed my rope and piled the loop right around his neck, and Alexander sot back on his haunches.

Well, it was about like roping a roaring hurricane. The instant he felt that rope Cap’n Kidd give a convulsive start, and made one mighty lunge for freedom. The lariat held, but the girths didn’t. They held jest long enough for Alexander to get jerked head over heels, and naturally I went along with him. But right in the middle of the somesault we taken, both girths snapped.

Me and the saddle and Alexander landed all in a tangle, but Cap’n Kidd jerked the saddle from amongst us, because I had my rope tied fast to the horn, Texas-style, and Alexander got loose from me by the simple process of kicking me vi’lently in the ear. He also stepped on my face when he jumped up, and the next instant he was hightailing it through the bresh in the general direction of Bear Creek. As I learned later he didn’t stop till he run into Pap’s cabin and tried to hide under my brother John’s bunk.

Meanwhile Cap’n Kidd had throwed the loop offa his head and come for me with his mouth wide open, his ears laid back and his teeth and eyes flashing. I didn’t want to shoot him, so I riz up and run for the trees. But he was coming like a tornado, and I seen he was going to run me down before I could get to a tree big enough to climb, so I grabbed me a sapling about as thick as my laig and tore it up by the roots, and turned around and busted him over the head with it, just as he started to r’ar up to come down on me with his front hoofs.

Pieces of roots and bark and wood flew every which a way, and Cap’n Kidd grunted and batted his eyes and went back on to his haunches. It was a right smart lick. If I’d ever hit Alexander that hard it would have busted his skull like a egg—and Alexander had a awful thick skull, even for a mule.

Whilst Cap’n Kidd was shaking the bark and stars out of his eyes, I run to a big oak and clumb it. He come after me instantly, and chawed chunks out of the tree as big as washtubs, and kicked most of the bark off as high up as he could rech, but it was a good substantial tree, and it held. He then tried to climb it, which amazed me most remarkable, but he didn’t do much good at that. So he give up with a snort of disgust and trotted off.

I waited till he was out of sight, and then I clumb down and got my rope and saddle, and started follering him. I knowed there warn’t no use trying to catch Alexander with the lead he had. I figgered he’d get back to Bear Creek safe. And Cap’n Kidd was the critter I wanted now. The minute I lammed him with that tree and he didn’t fall, I knowed he was the hoss for me—a hoss which could carry my weight all day without giving out, and likewise full of spirit. I says to myself I rides him or the buzzards picks my bones.

I snuck from tree to tree, and presently seen Cap’n Kidd swaggering along and eating grass, and biting the tops off of young sapling, and occasionally tearing down a good sized tree to get the leaves off. Sometimes he’d neigh like a steamboat whistle, and let his heels fly in all directions just out of pure cussedness. When he done this the air was full of flying bark and dirt and rocks till it looked like he was in the middle of a twisting cyclone. I never seen such a critter in my life. He was as full of pizen and rambunctiousness as a drunk Apache on the warpath.

I thought at first I’d rope him and tie the other end of the rope to a big tree, but I was a-feared he’d chawed the lariat apart. Then I seen something that changed my mind. We was close to the rocky cliffs which jutted up above the trees, and Cap’n Kidd was passing a canyon mouth that looked like a big knife cut. He looked in and snorted, like he hoped they was a mountain lion hiding in there, but they warn’t, so he went on. The wind was blowing from him towards me and he didn’t smell me.

After he was out of sight amongst the trees I come out of cover and looked into the cleft. It was kinda like a short blind canyon. It warn’t but about thirty foot wide at the mouth, but it widened quick till it made a kind of bowl a hundred yards acrost, and then narrowed to a crack again. Rock walls five hundred foot high was on all sides except at the mouth.

“And here,” says I to myself, “is a readymade corral!”

Then I lay to and started to build a wall to close the mouth of the canyon. Later on I heard that a scientific expedition (whatever the hell that might be) was all excited over finding evidences of a ancient race up in the mountains. They said they found a wall that could of been built only by giants. They was crazy; that there was the wall I built for Cap’n Kidd.

I knowed it would have to be high and solid if I didn’t want Cap’n Kidd to jump it or knock it down. They was plenty of boulders laying at the foot of the cliffs which had weathered off, and I didn’t use a single rock which weighed less’n three hundred pounds, and most of ’em was a lot heavier than that. It taken me most all morning, but when I quit I had me a wall higher’n the average man could reach, and so thick and heavy I knowed it would hold even Cap’n Kidd.

I left a narrer gap in it, and piled some boulders close to it on the outside, ready to shove ’em into the gap. Then I stood outside the wall and squalled like a cougar. They ain’t even a cougar hisself can tell the difference when I squalls like one. Purty soon I heard Cap’n Kidd give his war-neigh off yonder, and then they was a thunder of hoofs and a snapping and crackling of bresh, and he come busting into the open with his ears laid back and his teeth bare and his eyes as red as a Comanche’s war-paint. He sure hated cougars. But he didn’t seem to like me much neither. When he seen me he give a roar of rage, and come for me lickety-split. I run through the gap and hugged the wall inside, and he come thundering after me going so fast he run clean across the bowl before he checked hisself. Before he could get back to the gap I’d run outside and was piling rocks in it. I had a good big one about the size of a fat hawg and I jammed it in the gap first and piled t’others on top of it.

Cap’n Kidd arriv at the gap all hoofs and teeth and fury, but it was already filled too high for him to jump and too solid for him to tear down. He done his best, but all he done was to knock some chunks offa the rocks with his heels. He sure was mad. He was the maddest hoss I ever seen, and when I got up on the wall and he seen me, he nearly busted with rage.

He went tearing around the bowl, kicking up dust and neighing like a steamboat on the rampage, and then he come back and tried to kick the wall down again. When he turned to gallop off I jumped offa the wall and landed square on his back, but before I could so much as grab his mane he throwed me clean over the wall and I landed in a cluster of boulders and cactus and skun my shin. This made me mad so I got the lariat and the saddle and clumb back on the wall and roped him, but he jerked the rope out of my hand before I could get any kind of a purchase, and went bucking and pitching around all over the bowl trying to get shet of the rope. So purty soon he pitched right into the cliff wall and he lammed it so hard with his hind hoofs that a whole section of overhanging rock was jolted loose and hit him right between the ears. That was too much even for Cap’n Kidd.

It knocked him down and stunned him, and I jumped down into the bowl and before he could come to I had my saddle on to him, and a hackamore I’d fixed out of a piece of my lariat. I’d also mended the girths with pieces of the lariat, too, before I built the wall.

Well, when Cap’n Kidd recovered his senses and riz up, snorting and war-like, I was on his back. He stood still for a instant like he was trying to figger out jest what the hell was the matter, and then he turned his head and seen me on his back. The next instant I felt like I was astraddle of a ringtailed cyclone.

I dunno what all he done. He done so many things all at onst I couldn’t keep track. I clawed leather. The man which could have stayed onto him without clawing leather ain’t born yet, or else he’s a cussed liar. Sometimes my feet was in the stirrups and sometimes they warn’t, and sometimes they was in the wrong stirrups. I cain’t figger out how that could be, but it was so. Part of the time I was in the saddle and part of the time I was behind it on his rump, or on his neck in front of it. He kept reching back trying to snap my laig and onst he got my thigh between his teeth and would ondoubtedly of tore the muscle out if I hadn’t shook him loose by beating him over the head with my fist.

One instant he’d have his head betwixt his feet and I’d be setting on a hump so high in the air I’d get dizzy, and the next thing he’d come down stiff-laiged and I could feel my spine telescoping. He changed ends so fast I got sick at my stummick and he nigh unjointed my neck with his sunfishing. I calls it sunfishing because it was more like that than anything. He occasionally rolled over and over on the ground, too, which was very uncomfortable for me, but I hung on, because I was afeared if I let go I’d never get on him again. I also knowed that if he ever shaken me loose I’d had to shoot him to keep him from stomping my guts out. So I stuck, though I’ll admit that they is few sensations more onpleasant than having a hoss as big as Cap’n Kidd roll on you nine or ten times.

He tried to scrape me off agen the walls, too, but all he done was scrape off some hide and most of my pants, though it was when he lurched agen that outjut of rock that I got them ribs cracked, I reckon.

He looked like he was able to go on forever, and aimed to, but I hadn’t never met nothing which could outlast me, and I stayed with him, even after I started bleeding at the nose and mouth and ears, and got blind, and then all to onst he was standing stock still in the middle of the bowl, with his tongue hanging out about three foot, and his sweat-soaked sides heaving, and the sun was just setting over the mountains. He’d bucked nearly all afternoon!

But he was licked. I knowed it and he knowed it. I shaken the stars and sweat and blood out of my eyes and dismounted by the simple process of pulling my feet out of stirrups and falling off. I laid there for maybe a hour, and was most amazing sick, but so was Cap’n Kidd. When I was able to stand on my feet I taken the saddle and the hackamore off and he didn’t kick me nor nothing. He jest made a half-hearted attempt to bite me but all he done was to bite the buckle offa my gunbelt. They was a little spring back in the cleft where the bowl narrered in the cliff, and plenty of grass, so I figgered he’d be all right when he was able to stop blowing and panting long enough to eat and drink.

I made a fire outside the bowl and cooked me what was left of the b’ar meat, and then I lay down on the ground and slept till sunup.

When I riz up and seen how late it was, I jumped up and run and looked over the wall, and there was Cap’n Kidd mowing the grass down as ca’m as you please. He give me a mean look, but didn’t say nothing. I was so eager to see if he was going to let me ride him without no more foolishness that I didn’t stop for breakfast, nor to fix the buckle onto my gunbelt. I left it hanging on a spruce limb, and clumb into the bowl. Cap’n Kidd laid back his ears but didn’t do nothing as I approached outside of making a swipe at me with his left hoof. I dodged and give him a good hearty kick in the belly and he grunted and doubled up, and I clapped the saddle on him. He showed his teeth at that, but he let me cinch it up, and put on the hackamore, and when I got on him he didn’t pitch but about ten jumps and make but one snap at my laig. Well, I was plumb tickled as you can imagine. I clumb down and opened the gap in the wall and led him out, and when he found he was outside the bowl he bolted and dragged me for a hundred yards before I managed to get the rope around a tree. After I tied him up though, he didn’t try to bust loose. I started back towards the tree where I left my gunbelt when I heard hosses running, and the next thing I knowed Donovan and his five men busted into the open and pulled up with their mouths wide open. Cap’n Kidd snorted war-like when he seen ’em, but didn’t cut up no other way.

“Blast my soul!” says Donovan. “Can I believe my eyes? If there ain’t Cap’n Kidd hisself, saddled and tied to that tree! Did you do that?”

“Yeah,” I said.

He looked me over and said, “I believes it. You looked like you been through a sausage grinder. Air you still alive?”

“My ribs is kind of sore,” I said.

“—!” says Donovan. “To think that a blame half-naked hillbilly should do what the best hossmen of the West has attempted in vain! I don’t aim to stand for it! I knows my rights! That there is my hoss by rights! I’ve trailed him nigh a thousand miles, and combed this cussed plateau in a circle. He’s my hoss!”

“He ain’t, nuther,” I says. “He come from the Humbolts original, jest like me. You said so yoreself. Anyway, I caught him and broke him, and he’s mine.”

“He’s right, Bill,” one of the men says to Donovan.

“You shet up!” roared Donovan. “What Wild Bill Donovan wants, he gits!”

I reched for my gun and then remembered in despair that it was hanging on a limb a hundred yards away. Donovan covered me with the sawed-off shotgun he jerked out of his saddle holster as he swung down.

“Stand where you be,” he advised me. “I ought to shoot you for not comin’ and tellin’ me when you seen the hoss, but after all you’ve saved me the trouble of breakin’ him in.”

“So yo’re a hoss thief!” I said wrathfully.

“You be keerful what you calls me!” he roared. “I ain’t no hoss thief. We gambles for that hoss. Set down!”

I sot and he sot on his heels in front of me, with his sawed-off still covering me. If it’d been a pistol I would of took it away from him and shoved the barrel down his throat. But I was quite young in them days and bashful about shotguns. The others squatted around us, and Donovan says: “Smoky, haul out yore deck—the special one. Smoky deals, hillbilly, and the high hand wins the hoss.”

“I’m puttin’ up my hoss, it looks like,” I says fiercely. “What you puttin’ up?”

“My Stetson hat!” says he. “Haw! haw! haw!”

“Haw! haw! haw!” chortles the other hoss thieves.

Smoky started dealing and I said, “Hey! Yo’re dealin’ Donovan’s hand offa the bottom of the deck!”

“Shet up!” roared Donovan, poking me in the belly with his shotgun. “You be keerful how you slings them insults around! This here is a fair and square game, and I just happen to be lucky. Can you beat four aces?”

“How you know you got four aces?” I says fiercely. “You ain’t looked at yore hand yet.”

“Oh,” says he, and picked it up and spread it out on the grass, and they was four aces and a king. “By golly!” says he. “I shore called that shot right!”

“Remarkable foresight!” I said bitterly, throwing down my hand which was a three, five, and seven of hearts, a ten of clubs, and a jack of diamonds.

“Then I wins!” gloated Donovan, jumping up. I riz too, quick and sudden, but Donovan had me covered with that cussed shotgun.

“Git on that hoss and ride him over to our camp, Red,” says Donovan, to a big redheaded hombre which was shorter than him but jest about as big. “See if he’s properly broke. I wants to keep my eye on this hillbilly myself.”

So Red went over to Cap’n Kidd which stood there saying nothing, and my heart sunk right down to the tops of my spiked shoes. Red ontied him and clumb on him and Cap’n Kidd didn’t so much as snap at him. Red says: “Git goin’, cuss you!” Cap’n Kidd turnt his head and looked at Red and then he opened his mouth like a alligator and started laughing. I never seen a hoss laugh before, but now I know what they mean by a hoss laugh. Cap’n Kidd didn’t neigh nor nicker. He jest laughed. He laughed till the acorns come rattling down outa the trees and the echoes rolled through the cliffs like thunder. And then he reched his head around and grabbed Red’s laig and dragged him out of the saddle, and held him upside down with guns and things spilling out of his scabbards and pockets, and Red yelling blue murder. Cap’n Kidd shaken him till he looked like a rag and swung him around his head three or four times, and then let go and throwed him clean through a alder thicket.

Them fellers all stood gaping, and Donovan had forgot about me, so I grabbed the shotgun away from him and hit him under the ear with my left fist and he bit the dust. I then swung the gun on the others and roared, “Onbuckle them gunbelts, cuss ye!” They was bashfuller about buckshot at close range than I was. They didn’t argy. Them four gunbelts was on the grass before I stopped yelling.

“All right,” I said. “Now go catch Cap’n Kidd.”

Because he had gone over to where their hosses was tied and was chawing and kicking the tar out of them and they was hollering something fierce.

“He’ll kill us!” squalled the men.

“Well, what of it?” I snarled. “Gwan!”

So they made a desperate foray onto Cap’n Kidd and the way he kicked ’em in the belly and bit the seat out of their britches was beautiful to behold. But whilst he was stomping them I come up and grabbed his hackamore and when he seen who it was he stopped fighting, so I tied him to a tree away from the other hosses. Then I throwed Donovan’s shotgun onto the men and made ’em get up and come over to where Donovan was laying, and they was a bruised and battered gang. The way they taken on you’d of thought somebody had mistreated ’em.

I made ’em take Donovan’s gunbelt offa him and about that time he come to and sot up, muttering something about a tree falling on him.

“Don’t you remember me?” I says. “I’m Breckinridge Elkins.”

“It all comes back,” he muttered. “We gambled for Cap’n Kidd.”

“Yeah,” I says, “and you won, so now we gambles for him again. You sot the stakes before. This time I sets ’em. I matches these here britches I got on agen Cap’n Kidd, and yore saddle, bridle, gunbelt, pistol, pants, shirt, boots, spurs, and Stetson.”

“Robbery!” he bellered. “Yo’re a cussed bandit!”

“Shet up,” I says, poking him in the midriff with his shotgun. “Squat! The rest of you, too.”

“Ain’t you goin’ to let us do somethin’ for Red?” they said. Red was laying on the other side of the thicket Cap’n Kidd had throwed him through, groaning loud and fervent.

“Let him lay for a spell,” I says. “If he’s dyin’ they ain’t nothin’ we can do for him, and if he ain’t, he’ll keep till this game’s over. Deal, Smoky, and deal from the top of the deck this time.”

So Smoky dealed in fear and trembling, and I says to Donovan, “What you got?”

“A royal flush of diamonds, by God!” he says. “You cain’t beat that!”

“A royal flush of hearts’ll beat it, won’t it, Smoky?” I says, and Smoky says: “Yuh-yuh-yeah! Yeah! Oh, yeah!”

“Well,” I said, “I ain’t looked at my hand yet, but I bet that’s jest what I got. What you think?” I says, p’inting the shotgun at Donovan’s upper teeth. “Don’t you reckon I’ve got a royal flush in hearts?”

“It wouldn’t surprise me a bit,” says Donovan, turning pale.

“Then everybody’s satisfied and they ain’t no use in me showin’ my hand,” I says, throwing the cards back into the pack. “Shed them duds!”

He shed ’em without a word, and I let ’em take up Red, which had seven busted ribs, a dislocated arm and a busted laig, and they kinda folded him acrost his saddle and tied him in place. Then they pulled out without saying a word or looking back. They all looked purty wilted, and Donovan particularly looked very pecooliar in the blanket he had wropped around his middle. If he’d had a feather in his hair he’d of made a lovely Piute, as I told him. But he didn’t seem to appreciate the remark. Some men just naturally ain’t got no sense of humor.

They headed east, and as soon as they was out of sight, I put the saddle and bridle I’d won onto Cap’n Kidd and getting the bit in his mouth was about like rassling a mountain tornado. But I done it, and then I put on the riggins I’d won. The boots was too small and the shirt fit a mite too snug in the shoulders, but I sure felt elegant, nevertheless, and stalked up and down admiring myself and wishing Glory McGraw could see me then.

I cached my old saddle, belt and pistol in a holler tree, aiming to send my younger brother Bill back after ’em. He could have ’em, along with Alexander. I was going back to Bear Creek in style, by golly!

With a joyful whoop I swung onto Cap’n Kidd, headed him west and tickled his flanks with my spurs—them trappers in the mountains which later reported having seen a blue streak traveling westwardly so fast they didn’t have time to tell what it was, and was laughed at and accused of being drunk, was did a injustice. What they seen was me and Cap’n Kidd going to Bear Creek. He run fifty miles before he even pulled up for breath.

I ain’t going to tell how long it took Cap’n Kidd to cover the distance to Bear Creek. Nobody wouldn’t believe me. But as I come up the trail a few miles from my home cabin, I heard a hoss galloping and Glory McGraw bust into view. She looked pale and scairt, and when she seen me she give a kind of a holler and pulled up her hoss so quick it went back onto its haunches.

“Breckinridge!” she gasped. “I jest heard from yore folks that yore mule come home without you, and I was just startin’ out to look for—oh!” says she, noticing my hoss and elegant riggings for the first time. She kind of froze up, and said stiffly, “Well, Mister Elkins, I see yo’re back home again.”

“And you sees me rigged up in store-bought clothes and ridin’ the best hoss in the Humbolts, too, I reckon,” I said. “I hope you’ll excuse me, Miss McGraw. I’m callin’ on Ellen Reynolds as soon as I’ve let my folks know I’m home safe. Good day!”

“Don’t let me detain you!” she flared, but after I’d rode on past she hollered, “Breckinridge Elkins, I hate you!”

“I know that,” I said bitterly; “they warn’t no use in tellin’ me again—”

But she was gone, riding lickety-split off through the woods toward her home cabin and I rode on for mine, thinking to myself what curious critters gals was anyway.