Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

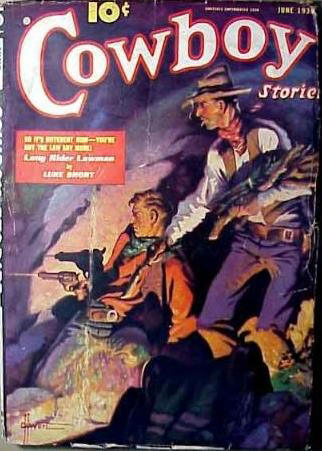

Published in Cowboy Stories, June 1936.

I’m a peaceable man, as law-abiding as I can be without straining myself, and it always irritates me for a stranger to bob up from behind a rock and holler, “Stop where you be before I blow your fool head off !”

This having happened to me I sat still on my brother Bill’s horse, because that’s the best thing you can do when a feller is p’inting a cocked .45 at your wishbone. This feller was a mean-looking hombre in a sweaty hickory shirt with brass rivets in his leather hat band, and he needed a shave. He said, “Who are you? Where you from? Where you goin’? What you aimin’ to do when you get there?”

I says, “I’m Buckner J. Grimes of Knife River, Texas, and I’m headin’ for Californy.”

“Well, what you turnin’ south for?” he asked.

“Ain’t this here the trail to Piute?” I inquired.

“Naw, ’tain’t,” he answered. “Piute’s due west of here.”

All at once he stopped and seemed to ponder, though his gun muzzle didn’t waver none. I was watching it like a hawk.

Pretty soon he give a kinda forced leer which I reckon he aimed for a smile, and said, “I’m sorry, stranger. I took you for somebody else. Just an honest mistake. This here trail leadin’ off to the west goes to Piute. T’other’n goes south to my claim. I took you for one of them blame claim jumpers.” He lowered his gun but didn’t put it back in the holster, I noticed.

“I didn’t know they was any claims in Arizona,” I says.

“Oh, yes,” says he, “the desert is plumb full of ’em. For instance,” says he, “I got a chunk of quartz in my pocket right now which is just bustin’ with pure ore. Light,” says he, fumbling in his pocket, “and I’ll show you.”

Well, I was anxious to see some ore, because Pap had told me that I was just likely to hit it rich in Californy; he said an idiot was a natural fool for luck, and I wanted to know what ore looked like when I seen some. So I clumb down off of brother Bill’s horse, and the stranger hauled something out of his pocket, but as he poked it out toward me, it slipped off his palm and fell to the ground.

Naturally I leaned over to pick it up, and when I done so, something went bam! and I seen a million stars. At first I thought a cliff had fell on me, but almost simultaneous I realized the stranger had lammed me over the head with his pistol barrel.

The lick staggered me, but I didn’t have to fall like I done. I done that instinctive hit on my side and tumbled over on my back and laid still, with my eyes so near shut he couldn’t tell that I was watching him through the slits. The instant he’d hit me he lifted his gun quick to shoot me if I didn’t drop, but my flop fooled him.

He looked down at me scornful, too proud of his smartness to notice that my limp hand was laying folded over a rock about the size of a muskmelon, and he says aloud to hisself, he says, “Another idiot from Texas! Huh! Think I’m goin’ to let you go on to Piute and tell ’em about bein’ turned back from the south trail, and mebbe give them devils an idee of what’s cookin’ up? Not much, I ain’t. I ain’t goin’ to waste no lead on you, neither. I reckon I’ll just naturally cut your throat with my bowie.”

So saying, he shoved his gun back in its holster and drawed his knife out of his boot, and stooped over and started fumbling with my neck cloth, so I belted him free and hearty over the conk with my rock. I then pushed his limp carcass off me and rose.

“If you’d been raised in Texas like I was,” I says to his senseless hulk more in sorrer than in anger, “you’d know just because a man falls it don’t necessarily mean he’s got his’n.”

He didn’t say nothing because he was out cold; the blood was oozing from his split scalp, and I knowed it would be hours before he come to hisself, and maybe days before he’d remember his own name.

I mounted brother Bill’s horse, which I’d rode all the way from Texas because it was better’n mine, and I paused and ruminated. Right there a narrer trail split off from the main road and turned south through a deep cleft in the cliffs, and the stranger had been lurking there at the turn.

Well, thinks I, something shady is going on down that there trail, else why should he hold me up when he thought I was going down it? I warn’t taking the south trail. I’d just stopped to rest my brother Bill’s horse in the shadder of the cliffs, and this ambushed gent just thought I was going to turn off. That there indicates a guilty conscience. Then, when he was convinced I wasn’t going south, he was going to cut my throat just so’s I couldn’t tell the folks at Piute about him stopping me. And he was lying about a claim. He didn’t have no hunk of quartz; that thing he’d taken out of his pocket was a brass button.

Well, I very naturally turned off down the south trail to see why he didn’t want me to. I went very cautious, with my gun in my right hand, because I didn’t aim to get catched off guard again. The thought occurred to me that maybe he was being hunted by a sheriff’s posse. Well, that wasn’t none of my business, but Pap always said my curiosity would be the ruin of me.

I rode on for about a mile, till I come to a place where the trail went up over a saddleback with dense thickets on each side. I left the trail and pushed through the thickets to see what was on the other side of the ridge; around Knife River they was generally somebody waiting to shoot somebody else.

I looked down into a big holler, and in the middle they was a big cluster of boulders, bigger’n a house. I seen some horses sticking out from behind them boulders, and a horse tied under a tree a little piece away. He was a very bright-colored pinto with a silver-mounted bridle and saddle. I seen the sun flash on the trappings on ’em.

I knowed the men must be on the other side of them rocks, and I counted nineteen horses. Well, nineteen men was more’n I wanted to tackle, in case they proved hostile to strangers, which I had plenty of reason to believe they probably would. So I decided to backtrack.

Anyway, them men was probably just changing brands on somebody else’s cows, or talking over the details of a stagecoach holdup, or some other private enterprise like that which wasn’t nobody’s business but their’n. So I turned around and went back up the trail to the forks again.

When I passed the stranger I had hit with the rock he was still out, and I kinda wondered if he’d ever come to. But that wasn’t none of my business neither, so I just dragged him under bushes where he’d be in the shade in case he did, and rode on down the west trail. I figgered it couldn’t be more’n a few miles to Piute, and I was getting thirsty.

And sure enough, after a few miles I come upon the aforesaid town baking in the sun on a flat with hills on all sides—just a cluster of dobe huts with Mexican women and kids littered all over the place—and dogs, and a store and a little restaurant and a big saloon. It wasn’t much past noon and hotter’n hell.

I tied brother Bill’s horse to the hitching rack alongside the other horses already tied there, in the shade of the saloon, and I went into the saloon myself. They was a good-sized bar and men drinking at it, others playing poker at tables.

Well, I judged it wasn’t very usual that a stranger come to Piute, because when I come in everybody laid down their whisky glass or their hand of cards and stared at me without no expression on their faces, and I got fidgety and drunk five or six fingers of red licker to cover my embarrassment.

They was a kind of restless shuffling of boots on the floor, and spitting into the sawdust, and men tugging at their mustaches, and I wondered am I going to have to shoot my way out of this joint; what kind of a country is this anyway.

Just then a man lumbered up to the bar and the men drinking at the bar kinda surged around me and him, and some of them playing poker rose up from their tables and drifted over behind me, or would have, if I hadn’t quick put my back against the bar. This feller was nigh as tall as me, and a lot heavier. He had a big mustache like a walrus.

“Who be you?” he inquired suspiciously.

“I’m Buckner J. Grimes,” I said patiently. “I’m from Texas, and I’m just passin’ through. I’m headin’ for Californy.”

“What’s the ‘J’ for?” he asked.

“Jeopardy,” I said.

“What’s that mean?” he next demanded.

“I dunno,” I confessed. “It come out of a book. I reckon it means somethin’ pertainin’ to a jeopard.”

“Well, what’s a jeopard?” he asked.

“It’s a spotted critter like a panther,” said one of the men. “I seen one in a circus once in Santa Fe.”

The big feller studied over this for a while, and then he said have a drink, so we all drunk.

“Do you know Swag McBride?” he asked at last.

“I never heard tell of him,” I said. Everybody was watching me when he asked me, and some of them had their hands on their guns. But when I said I didn’t know him they kinda relaxed and went back to playing poker and drinking licker. I reckon they believed me; Pap always said I had a honest face; he said anybody could tell I didn’t have sense enough to think up a lie.

“Set down,” said the big man, easing his bulk ponderously into a chair and sinking his mustaches into a tub of beer. “I’m Navajo Beldon. I’m boss of Piute and all the surroundin’ country, and don’t let nobody tell you no different. Either a man is for me or he’s against me, and if he’s against me he’s for Swag McBride and don’t belong in this town at all.”

“Who’s Swag McBride?” I asked.

“A cross between a rattlesnake and a skunk,” said Beldon, gulping his beer. “But don’t say ‘skunk’ around him les’n you want to get killed. When the vigilantes run him outa Nevada they sent him down the trail with a dead polecat tied around his neck as a token of affection and respect. Skunks has been a sore spot with him ever since. If anybody even mentions one in his hearin’ he takes it as a personal insult and acts accordingly. He’s lightnin’ with a gun, and when souls was handed out, Nature plumb forgot to give him one. He run this town till I decided to take it over.”

He wiped his mustaches with the back of his hand, and said, “We had a showdown last week, and decreases in the population was sudden and generous. But we run them rats into the hills where they’ve been skulkin’ ever since, if they ain’t left the country entirely.”

I thought about them fellers I seen up in the hills, but I didn’t say nothing. I was raised in a country where keeping your mouth shut is an art practiced by everybody which wants to live to a ripe old age.

“This here country has to have a boss of some kind,” says “Navajo,” pouring me a drink. “Ain’t no law here, and somebody’s got to kinda run things. I ain’t no saint, but I’m a lot better man than Swag McBride. If you don’t believe it, go ask the citizens of Piute. Man’s life is safe here with me runnin’ things, long’s he keeps his nose outa my business, and a woman can walk down the street without bein’ insulted by some tough. Honest to gosh, if I was to tell you some of the things McBride and his devils has pulled—”

“Things looks peaceful enough now,” I admitted.

“They are, while I’m in the saddle,” says Beldon. “Say, how would you like to work for me?”

“Doin’ what?” I ask.

“Well,” he says, “I got considerable cattle, besides my interests in Piute. These men you see here ain’t all the boys I got workin’ for me, of course. They’s a bunch now down near Eagle River, drivin’ a herd up from the border, which ain’t so terrible far from you, you know.”

“You buy cattle in Mexico?” I ask.

“Well,” he says, “I gets quite a lot of steers from across the line. I has to have men watchin’ all the time to keep them greasers from comin’ over and stealin’ everything I got. What’s that?”

Outside come a thunder of hoofs and a voice yelled, “Beldon! Beldon!”

“Who’s that?” demanded Beldon, scrambling up and grabbing his gun.

“It’s Richards!” called one of the men, looking out of the winder with a rifle. “He’s foggin’ it up the south trail like the devil was ridin’ behind him.”

Beldon started lumbering toward the door, but about that time the horse slid to a gravel-scattering halt at the edge of the porch, and a man come storming in, all plastered with sweat and dust.

“What’s eatin’ you, Richards?” demanded Navajo.

“The greasers!” yelped Richards. “Early this mornin’ we run a herd of Diego Gonzales’ cattle across the line, and you know what happened? We hadn’t hardly more’n got back across the border when his blame vaqueros overtook us and shot up every man except me, and run them steers back home again!”

“What?” bellered Navajo, with his mustaches quivering in righteous wrath. “Why, them thievin’, yeller polecats! Ain’t they got no respect for law and order? What air we a-comin’ to? Ain’t they no honest men left besides me? Does they think they can treat me like that? Does they think we’re in the the cow business for our health? Does they think they can tromple on us after we’ve went to the trouble and expense of stealin’ them steers ourselves?

“Donnelly, take your men and light out! I’ll show them greasers they can’t steal my critters and get away with it. You fetch them cows back if you have to foller ’em right into Diego’s patio—blast his thievin’ soul!”

The feller he called Donnelly got up and told his men to come on, and they took a drink at the bar, and drawed up their gun belts and went stomping out toward the hitching rack. Richards went along to guide ’em.

“Don’t you wanta go?” says Navajo to me, still snorting with his indignation. “The boys may need help, and I can tell from the way you wear your guns that you know how to handle ’em. I’ll pay you well.”

Well, if they is anything I despises it’s a darned thief, so I told Beldon I’d go along and help recover his property. I left him bellering his grievances to the bald-headed old bartender and his Mexican boy helper, which was all that was left in the saloon.

Richards had changed his saddle onto a fresh horse, and as we rode off I looked at the horse which he’d rode in. It was a pinto and it seemed to me like I’d saw it somewheres but I couldn’t remember. It was so sweaty and dusty it was mighty near disguised.

We headed south along the dusty trail, nine or ten of us, Richards leading, and was soon out of sight of Piute. Them fellers was riding like Mexico was right over the next rise, but the miles went past, and I decided they was just reckless, damn fools. I kept trying to remember where I’d seen that pinto of Richards’, and all of a sudden I remembered.

The trail dipped ahead of us down into a tangle of cliffs and canyons, and Richards had drawed ahead of the rest of us. He turned to motion us to hurry, and as he turned, the sun flashed from the silver trappings on his saddle and bridle, and, like a shot, I remembered—I remembered where I’d seen them trappings, and where I’d seen that pinto. It was the horse I’d saw tied near them big rocks away to the east of Piute.

I involuntarily sat brother Bill’s horse back on his haunches. The rest of the gang swept on without noticing, but I sat there and thunk. If Richards was with that gang east, how could he be with the bunch driving cattle acrost the border away to the south of Piute? He come up the south trail into Piute, but what was to prevent him from cutting through the hills and hitting that trail just below the town? Richards had lied to Beldon; and Beldon had said that if a man wasn’t for him, he was for McBride.

I reined up onto a knob, and stared off eastward, and pretty soon I seen what I expected to see—a fog of rolling dust, sweeping from southeast to northwest—toward Piute. I knowed what was raising that dust: men on horses, riding hard.

I looked south for Donnelly and his men. They was just passing out of sight in a big notch with sheer walls on each side. I yelled but they didn’t hear me. Richards had pulled ahead of them by a hundred yards, and was already through the notch and out of sight. They all thundered into the notch and passed out of sight. And then it sounded like all the guns in southern Arizona let go at once. I wheeled and rode for Piute as hard as brother Bill’s horse could leg it.

The dust on the horizon disappeared behind a big boulder that jutted right up into the sky. Then, after a while, ahead of me, I heard a sudden crackle of gunfire, and what sounded like a woman screaming, and then everything was still again.

Ahead of me the trail made the bend that would bring me in sight of Piute. I left the trail and took to the thickets. Brother Bill’s horse was snorting and trembling, nigh done in. The town was awful quiet—not a soul in sight, and all the doors closed. I circled the flat, tied Bill’s horse in a thicket back of the saloon, and stole toward the back door, with my guns in my hands.

They wasn’t no horses tied at the hitching rack. Everything was awful quiet except for the flies buzzing around the blood puddles on the floor. The old bartender was laying across the bar with a gun still in his hand. He’d stopped plenty lead. His Mexican boy was slumped down near the door with his head split open—looked like he’d been hit with an ax. A stranger I’d never saw was stretched out in the dust before the porch, with a bullet hole in his skull. He was a tall, dark, hard-looking cuss. A gun with one empty chamber was laying nigh his right hand.

I believed they’d captured Navajo Beldon alive. His carcass wasn’t nowhere to be seen, and then the tables and chairs was all busted, just like I figgered they’d be after a gang of men had hog tied Beldon. That would be a job that’d wreck any saloon. They was empty cartridges and a broke knife on the floor, and buttons tore offa fellers’ shirts, and a smashed hat, and a notebook, like things gets scattered during a free for all.

I picked up the notebook and on the top of the first page was wrote, “Swag McBride owes me $100 for that there job over to Braxton’s ranch.”

I stuck it in my pocket but I didn’t need no evidence to know who’d raided Piute.

I looked out cautious into the town. Nobody in sight and all doors and winders closed. Then come a sudden rumble of horses’ hoofs and I jumped back out of the doorway and looked through a winder. Seven horsemen swept into the village out of a trail that wound up through the thickets back of the town; but they didn’t stop.

They cantered on down the south trail, with rifles in their hands. They didn’t look toward the saloon, and nobody stuck their head out of a house to tell ’em about me, though somebody must of seen me sneak into town. Evidently the citizens was playing strict neutral, which is wise when two gangs is slaughtering each other—if you can do it.

As soon as the riders was out of town I run back through the saloon and hustled up the hillside, paralleling the trail they’d come down. Who says all this wasn’t none of my business? Beldon had hired me and I’d been a pretty excuse for a man if I’d left him in the lurch.

I hadn’t gone far when I heard men talking—leastways, I heard one man talking. It was Beldon and he was bellering like a bull.

A minute later I come onto a log cabin, plumb surrounded with trees. Five horses was tied outside. The bellering was coming from inside the cabin, and I could hear somebody else talking in a kinda sneery, gloating voice. I snuck up to the rear winder and peered in, well aware that I was risking my life. But the winder was boarded up and I peeked through a crack.

Plenty of light come in through the cracks, though, and I seen Beldon, with blood oozing from a cut in his scalp, setting in a busted chair by a dusty old table, and looking like a trapped grizzly. Four other men was standing acrost the table from him, betwixt him and the door, with their guns leveled at him. One of them was awful tall, and rangy and quick in his motions, like a catamount. He combed his long drooping mustache with one gun muzzle whilst he poked the other’n into Beldon’s ear and screwed it around till Navajo cussed something terrible.

“Huh!” said this gent. “Boss of Piute! Hah! A fine boss you be. First and biggest mistake you made was trustin’ Richards. He was plumb delighted to sell you out. You thought he was with your men on Eagle River, didn’t you? Well, he was with me in the hills east of here all mornin’, whilst we laid our plans to get you.

“He sneaked away from your bunch on Eagle River last night. He brung you that lie about them cattle bein’ stole just so I could get your men out of the way. I knowed you’d send every man you had. You won’t ever see ’em no more. Richards will lead ’em into a trap in Devil’s Gorge where my men done laid an ambush for ’em. Probably they’re sizzlin’ in hell by this time. Them seven fellers I just sent down the trail will join the rest of my men at Devil’s Gorge, and they’ll clean out your outfit on Eagle River. I’m makin’ a clean sweep, Beldon.”

“I’ll get you yet, McBride,” promised Beldon thickly, gnashing his teeth under his heavy mustache.

McBride combed his mustache very superior. I was wondering why they’d taken Beldon alive. He wasn’t even tied up. I seen his fingers clinch and quiver on the table. I knowed he was liable to make a break for it any minute and get shot down, and I was in a stew. I could start shooting through the winder, of course, and snag most of ’em, but one of ’em was bound to get Beldon sure.

I knowed very well that at the first alarm they’d perforate him. I wisht I had a shotgun, because then I mighta got ’em all with one blast—probably including Beldon. But all I had was a couple of .45s and a clear conscience. If I could only let Beldon know that I was on hand, maybe he might get foxy and do something smart to help hisself, instead of busting loose and getting killed like I knowed he was going to do any minute. The veins in his neck swelled and his face got purple and his whiskers bristled.

All at once McBride said, “I’ll let you go, alive, if you’ll tell me where you got your money hid. I know you got several thousand bucks.”

So that was why they taken him alive. I mighta knowed it. But the mention of money reminded me of something and that put a idee into my head. I pulled out the notebook I found and tore out the first page and begun work with a pencil stub I had in my pocket. I didn’t write nothing. What I wanted to do was to slip Beldon a message he could understand, but that wouldn’t mean nothing to McBride, in case he seen it.

I remembered that talk about a Jeopard, when I first met Beldon, so I drawed a picture of a animal like a panther. But I couldn’t remember whether that feller from Santa Fe said a Jeopard had spots or stripes. Seemed like he said stripes, so I put a big un’ down the critter’s back. Beldon would know that pitcher meant that Buckner Jeopardy Grimes was lurking near, ready to help him the first chance I got, and, knowing that, he wouldn’t do nothing reckless.

Whilst I was doing this Beldon was thinking over what McBride had just said to him. He didn’t crave a lead bath no more’n the average man, and he was one of these here trusting critters which believes everybody keeps their word. It’s hard to credit, I know, but it looked like he actually believed McBride would keep his’n, and let him go if he told where he hid his dough.

McBride didn’t fool me none. I knowed very well the instant he told ’em, Beldon would get riddled. I knowed McBride itched to kill him. I seen it in the twist of his thin lips, and the nervous twitch of his hand as he pulled at his mustache. I read the killer’s hunger in his yeller eyes which blazed like a cat’s. But Navajo didn’t seem to recognize them signs. He was awful slow thinking in some ways.

McBride was pulling his mustache and just getting ready to say something, when I took a pebble and throwed it over the shack so it hit the stoop and made a racket. Instantly they all wheeled and covered the door, and I throwed my wadded-up paper through the crack in the winder boards, so it landed on the table right in front of Beldon. But he never seen it.

He’d rose halfway up like he was going to make his break, but quick as a flash McBride wheeled and covered him again, with his lip drawed back so his teeth showed like a wolf’s fang, and his eyes was slits of fire. If it hadn’t been for that dough he wanted, he’d have shot Beldon down right then. I seen his finger quiver on his trigger, and I had him lined over my sights.

But he didn’t shoot. He snapped, “You fools, keep him covered! I’ll see to this!”

The other three turned their guns on Beldon and he sunk back in his chair with a gusty sigh. They was a hard layout—one short, one tall, one with a scarred face. McBride stepped quick to the door and jerked it open and poked his gun out.

“Nothin’ out here,” he snorted. “Must have been a woodpecker.”

I was sweating and shaking like a leaf in my nervousness, waiting for Beldon to see that wad of paper laying right in front of him, but he never noticed it. He hadn’t seen it fall, and a wad of paper didn’t mean nothing to him. He couldn’t think of but one thing at a time. He had nerve and men liked him; that’s the only reason he ever got to be a chief.

McBride turned around and stalked back across the cabin.

“Well,” he said, “are you goin’ to tell me where the dough is?”

“I reckon I gotta,” mumbled Beldon heavily, and I cussed bitterly under my breath. Beldon was a goner. All I could do was start shooting and get as many of ’em as I could. But they was sure to drill him. Then McBride seen that wadded-up paper. He wasn’t like Beldon; he was observant and keen-witted. He remembered that paper hadn’t been there a few minutes before. He grabbed it.

“What’s this?” he demanded, and my heart sunk clean to my boot tops. He wouldn’t know what it meant, but it was gone out of Beldon’s reach for good.

McBride started smoothing it out.

“Why,” says he, “it’s got my name on it, in your handwritin’, Joe.”

“Lemme see,” said the tall feller, getting up and reached toward it. But McBride had straightened the paper all the way out, and all at once his face went livid. For a second you could of heard a pin drop. McBride stood like a froze statue, only his eyes alive and them points of hell fire, whilst the other hombres gaped at him.

Then he give a shriek like a catamount, and throwed that piece of paper into Joe’s face, and his gun jumped and spurted red. Joe flopped to the floor, kicking and twitching. The other two fellers was white and wild-looking, but the short one says, kind of choking, “By Heaven, McBride, you can’t do that to my pal!”

His gun jerked upward, but McBride’s spoke first. Shorty’s gun exploded into the floor and he slumped down on top of Joe. It was at that instant I kicked a board off the winder and shot “Scarface” through the ear. McBride howled in amazement and our guns crashed simultaneous. Or rather, I reckon mine was the split fraction of a second the first, because his lead fanned my ear and mine knocked him down dead on the floor.

I then climbed through the winder into the cabin where the blue smoke was drifting in clouds and the dead men was laying still on the floor. If the fight had been a tornado hitting the shack it couldn’t have been no briefer nor done no more damage. Beldon had had presence of mind enough to fall down behind the table when the fireworks started, and he now rose and glared at me like he thought I was a ghost.

“What the hell!” he inquired lucidly.

“We ain’t got no time to waste,” I told him. “We got to take to the woods. Them seven men McBride sent south ain’t out of hearin’. They’ll hear the shots and be back. They’ll know it wouldn’t take all them shots to cook your goose, and they’ll come back and investigate.”

He lurched up, and I seen he was lame in one leg.

“I got it sprained in the fight,” he grunted. “They was in Piute and stormin’ my saloon before I knowed what was happenin’. Help me back to the saloon. My dough’s hid under the bar. If all my men’s been wiped out, we got to travel, and I got to get my dough. They’s horses in a corral not far from the saloon.”

“All right,” I said, picking up the wad of paper I’d throwed through the winder, but not stopping to discuss it. “Let’s go,” I said, and we went.

If anybody thinks it’s a cinch to help a man as big as Navajo Beldon down a mountain trail with a sprained ankle, he’s loco as hell. He had to kind of hop on one leg and I had to act as his other leg, and before we was halfway down I felt like throwing him the rest of the way down and washing my hands of the whole business. Of course, I didn’t, though.

Piute was just as quiet and empty as before—heads bobbing a little way out of doors to gawp at us, then jerking back quick, and everything still and breathless under the hot sun.

Beldon cussed at the sight of the dead men in the bar, and he sounded sick.

“I feel like a skunk,” he said, “runnin’ out like this and leavin’ Piute to the mercies of them devils which follered McBride. But what else can I do? I—”

“Look out!” I yelped, jumping back out of the doorway and blazing away with my six-gun, as there come a rattle of hoofs up the south trail and them seven devils of McBride’s come storming back into town. They’d already seen me, before I fired, and they howled like wolves and come at a dead run.

At the crack of my six-shooter one of ’em went out of his saddle and laid still, and they swung aside and raced behind a old dobe house right across from the saloon.

Beldon was cussing and hitching hisself to one of the winders with a rifle he’d brung from the cabin, and I took the other winder. The old dobe they’d took cover behind didn’t have no roof and the wall was falling down, but it made a prime fort, and in about a second lead was smacking into the saloon walls, and ripping through the winders and busting bottles behind the bar, and when Beldon seen his licker wasted that way he hollered like a bull with its tail caught in the corral gate.

They’d punched loop holes in the dobe. All we could see was rifle muzzles and the tops of their hats now and then. We was shooting back, of course, but from the vigor of their profanity I knowed we wasn’t doing nothing but knocking dust into their faces.

“They’ve got us,” said Beldon despairingly. “They’ll hold us here till the rest of them devils comes up. Then they’ll rush us from three or four sides at once and finish us.”

“We could sneak out the back way,” I said, “but we’d have to go on foot, and with your ankle we couldn’t get nowheres.”

“You go,” he said, sighting along his rifle barrel and throwing another slug into the dobe. “I’m done. I couldn’t get away on this lame leg. I’ll hold ’em whilst you sneak off.”

This being too ridiculous to answer, I maintained a dignerfied silence and said nothing outside of requesting him not to be a fool.

A minute later he give a groan like a buffler bull with the bellyache.

“We’re sunk now!” says he. “Here come the rest of them!”

And sure enough I heard the drum of more hoofs up the south trail, and the firing acrost the way lulled, as the fellers listened. Then they give a yell of extreme pleasure, and started firing again with wild hilarity.

“I ain’t lived the kind of life I ought to have,” mourned Beldon. “My days has been full of vanity and sin. The fruits of the flesh is sweet to the tongue, Buckner, but they play hell with the belly. I wish I’d given more attention to spiritual things, and less to gypin’ my feller-man—Are you listenin’?”

“Shut up!” I said fretfully. “They is a feller keeps stickin’ his head up behind that dobe, and the next time he does it I aim to ventilate his cranium, if you don’t spoil my aim with your gab.”

“You ought to be placin’ your mind on higher things at a time like this,” he reproved. “We’re hoverin’ on the brink of Eternity, and it’s a time when you should be repentin’ your sinful ways, like me, and shakin’ the dust of the flesh off your feet—Hell fire and damnation!” he roared suddenly, heaving up from behind the winder sill. “That ain’t McBride’s men! That’s Donnelly!”

The fellers behind the dobe found that out just then, but it didn’t do ’em no good. Donnelly and six of the men which had rode out with him come swinging in behind ’em, and they was ten more men with him I hadn’t never saw before. The six men behind the dobe run for their horses, but they didn’t have a chance. They’d been so sure it was their pals they didn’t pay much attention, and Donnelly and his boys was right behind ’em before they realized their mistake.

Of course, we couldn’t see what was happening behind the dobe. We just saw Donnelly and his hombres sweep around it, and then heard the guns roaring and men yelling. But by the time I’d run acrost the street and rounded the corner of the dobe, the McBride gang was a thing of the past, and three of Donnelly’s men was down with more or less lead in ’em.

“Carry ’em over to the saloon, boys,” said Donnelly, who had a broke arm in a blood-soaked sleeve hisself. We done so, whilst Navajo, who had got as far as the porch on his game leg, bellered and waved his smoking rifle like a scepter.

“Lay ’em on the floor and pour licker down ’em,” said Beldon. “What the hell happened?”

“Richards led us into a trap,” grunted Donnelly, taking a deep swig hisself. “They got Bill and Tom and Dick, but I plugged Richards as he took to the brush. They’d have snagged us all though, if it hadn’t been for these boys. They was with the outfit on Eagle River, and when Richards rode off last night they got suspicious and trailed him. They was just south of Devil’s Gorge where the ambush was laid, when they heard the shootin’, and they come up in time to give us a hand.”

“And if it hadn’t been for Grimes, here,” grunted Beldon, “McBride would have been boss of Piute right now. What you lookin’ at?”

“This here paper,” I said. “I’m tryin’ to figger out why a pitcher of a jeopard would start McBride to killin’ his own men.”

“Lemme see,” says he, and he took it and looked at it, and said, “Why, hell, no wonder! It’s got McBride’s name at the top, over that pitcher. He thought that feller Joe had drawed it to insult him.”

“But the pitcher of a jeopard—” I protested.

“You might have meant it for a jeopard,” he said, “but it looks a darn sight more like a striped skunk to me, and I reckon that’s what McBride took it for. I told you he went crazy when the subject of skunks was brung up. Never mind that; a hombre as quick with a gun as you are don’t need no other accomplishments; how about a steady job with me?”

“What for?” I said. “With the McBride gang cleaned out I don’t see what they is for an able-bodied man in these parts. Besides, I see art ain’t appreshiated here. I’m goin’ on to Californy, like Pap told me to.”