Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

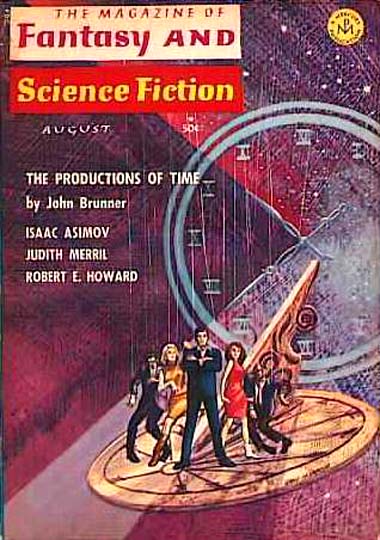

Published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Vol. 31, No. 2 (August 1966).

“’Twas in the merry month of May,

When all sweet buds were swellin’,

Sweet William on his death-bed lay

For the love of Barbara Allen.”

My grandfather sighed and thumped wearily on his guitar, then laid it aside, the song unfinished.

“My voice is too old and cracked,” he said, leaning back in his cushion-seated chair and fumbling in the pockets of his sagging old vest for cob-pipe and tobacco. “Reminds me of my brother Joel. The way he could sing that song. It was his favorite. Makes me think of poor old Rachel Ormond, who loved him. She’s dyin’, her nephew Jim Ormond told me yesterday. She’s old; older’n I am. You never saw her, did you?”

I shook my head.

“She was a real beauty when she was young, and Joel was alive and lovin’ her. He had a fine voice, Joel, and he loved to play his guitar and sing. He’d sing as he rode along. He was singin’ ‘Barbara Allen’ when he met Rachel Ormond. She heard him singin’ and came out of the laurel beside the road to listen. When Joel saw her standin’ there with the mornin’ sun behind her makin’ jewels out of the dew on the bushes, he stopped dead and just stared like a fool. He told me it seemed as if she was standin’ in a white blaze of light.

“It was mornin’ in the mountains and they were both young. You never saw a mornin’ in spring, in the Cumberlands?”

“I never was in Tennessee,” I answered.

“No, you don’t know anything about it,” he retorted, in the half humorous, half petulant mood of the old. “You’re a post oak gopher. You never saw anything but sand drifts and dry shinnery ridges. What do you know about mountain sides covered with birch and laurel, and cold clear streams windin’ through the cool shadows and tinklin’ over the rocks? What do you know about upland forests with the blue haze of the Cumberlands hangin’ over them?”

“Nothing,” I answered, yet even as I spoke, there leaped crystal clear into my mind with startling clarity the very image of the things of which he spoke, so vivid that my external faculties seemed almost to sense it—I could almost smell the dogwood blossoms and the cool lush of the deep woods, and hear the tinkle of hidden streams over the stones.

“You couldn’t know,” he sighed. “It’s not your fault, and I wouldn’t go back, myself, but Joel loved it. He never knew anything else, till the war came up. That’s where you’d have been born if it hadn’t been for the war. That tore everything up. Things didn’t seem the same afterwards. I came west, like so many Tennessee folks did. I’ve done well in Texas—better’n I’d ever done in Tennessee. But as I get old I get to dreamin’.”

His gaze was fixed on nothing, and he sighed deeply, wandering somewhat in his mind as the very old are likely to do at times.

“Four years behind Bedford Forrest,” he said at last. “There never was a cavalry leader like him. Ride all day, shootin’ and fightin’, bed down in the snow—up before midnight, ‘Boots and Saddles’, and we were off again.

“Forrest never hung back. He was always in front of his men, fightin’ like any three. His saber was too heavy for the average man to use, and it carried a razor edge. I remember the skirmish where Joel was killed. We come suddenly out of a defile between low hills and there was a Yankee wagon train movin’ down the valley, guarded by a detachment of cavalry. We hit that cavalry like a thunder-bolt and ripped it apart.

“I can see Forrest now, standin’ up in his stirrups, swingin’ that big sword of his, yellin’ ‘Charge! Holler, boys, holler!’ And we hollered like wild men as we went in, and none of us cared if we lived or died, so long as Forrest was leadin’ us.

“We tore that detachment in pieces and stomped and chased the pieces all up and down the valley. When the fight was over, Forrest reined up with his officers and said, ‘Gentlemen, one of my stirrups seems to have been shot away!’ He had only one foot in a stirrup. But when he looked, he saw that somehow his left foot had come out of the stirrup, and the stirrup had flopped up over the saddle. He’d been sittin’ on the stirrup leather, and hadn’t noticed, in the excitement of the charge.

“I was right near him at the time, because my horse had fell, with a bullet through its head, and I was pullin’ my saddle off. Just then my brother Joel came up on foot, smilin’, with the morning sun behind him. But he was dazed with the fightin’ because he had a strange look on his face, and when he saw me he stopped short, as if I was a stranger. Then he said the strangest thing: ‘Why, granddad!’ he said, ‘You’re young again! You’re younger’n I am!’ Then the next second a bullet from some skulkin’ sniper knocked him down dead at my feet.”

Again my grandfather sighed and took up his guitar.

“Rachel Ormond nearly died,” he said. “She never married, never looked at any other man. When the Ormonds came to Texas, she came with ’em. Now she’s dyin’, up there in their house in the hills. That’s what they say; I know she died years ago, when news of Joel’s death came to her.”

He began to thrum his guitar and sing in the curious wailing chant of the hill people.

“They sent to the east, they sent to the west,To the place where she was dwellin’,Sweet William’s sick, and he sends for you,For the love of Barbara Allen.”

My father called to me from his room on the other side of the house.

“Go out and stop those horses from fighting. I can hear them kicking the sides out of the barn.”

My grandfather’s voice followed me out of the house and into the stables. It was a clear still day and his voice carried far, the only sound besides the squealing and kicking of the horses in the stables, the crowing of a distant cock, and the clamor of sparrows among the mesquites.

Barbara Allen! An echo of a distant and forgotten homeland among the post-oak covered ridges of a barren land. In my mind I saw the settlers forging westward from the Piedmont, over the Alleghenies and along the Cumberland River—on foot, in lumbering wagons drawn by slow-footed oxen, on horse-back—men in broadcloth and men in buckskin. The guitars and the banjoes clinked by the fires at night, in the lonely log cabins, by the stretches of river black in the starlight, up on the long ridges where the owls hooted. Barbara Allen—a tie to the past, a link between today and the dim yesterdays.

I opened the stall and went in. My mustang Pedro, vicious as the land which bred him, had broken his halter and was assaulting the bay horse with squeals of rage, wicked teeth bared, eyes flashing, and ears laid back. I caught his mane, jerked him around, slapping him sharply on the nose when he snapped at me, and drove him from the stall. He lashed out wickedly at me with his heels as he dashed out, but I was watching for that and stepped back.

I had forgotten the bay horse. Stung to frenzy by the mustang’s attack, he was ready to kill anything that came within his reach. His steel shod hoof barely grazed my skull, but that was enough to dash me into utter oblivion.

My first sensation was of movement. I was shaken up and down, up and down. Then a hand gripped my shoulder and shook me, and a voice bawled in an accent which was familiar, yet strangely unfamiliar: “Hyuh, you, Joel, yuh goin’ to sleep in yo’ saddle!”

I awoke with a jerk. The motion was that of the gaunt horse under me. All about me were men, gaunt and haggard in appearance, in worn grey uniforms. We were riding between two low hills, thickly timbered. I could not see what lay ahead of us because of the mass of men and horses. It was dawn, a grey unsteady dawn that made me shiver.

“Sun soon be up now,” drawled one of the men, mistaking my feeling. “We’ll have fightin’ enough to warm our blood purty soon. Old Bedford ain’t marched us all night just for fun. I heah theah’s a wagon-train comin’ down the valley ahaid of us.”

I was still struggling feebly in a web of illusion. There was a sense of familiarity about all this, yet it was strange and alien, too. There was something I was striving to remember. I slipped a hand into my inside pocket, as if by instinct, and drew out a photograph, an old-fashioned picture. A girl smiled bravely at me, a beautiful girl with tender lips and brave eyes. I replaced it, shaking my head dazedly.

Ahead of us a low roar went up. We were riding out of the defile, and a broad valley lay spread out before us. Along this valley moved a train of clumsy, lumbering wagons. I saw men on horseback—men in blue, whose appearance and whose horses were fresher than ours. The rest is dim and confused.

I remember a bugle blown. I saw a tall rangy man on a great horse at the head of our column draw his sword and stand up in his stirrups, and his voice rang above the blast of the bugle: “Charge! Holler, boys, holler!”

Then there was a shout that rent the skies apart and we stormed out of the defile and down into the valley like a mountain torrent. I was like two men—one that rode and shouted and slashed right and left with a reddened saber, and one who sat wondering and fumbling for something illusive that he could not grasp. But the conviction was growing that I had experienced all this before; it was like living an episode forewarned in a dream.

The blue line held for a few minutes, then it broke in pieces before our irresistible onslaught, and we hunted them up and down the valley. The battle resolved itself into a hundred combats, where men in blue and men in grey circled each other on stamping, rearing horses, with bright blades glittering in the rising sun.

My gaunt horse stumbled and went down, and I pulled myself free. In my daze I did not take off his saddle. I walked toward a group of officers and men who were clustered about the tall man who had led the charge. As I approached, I heard him say: “Gentlemen, it seems the enemy have shot off one of my stirrups.”

Then before I could hear anything else, I came face to face with a man I recognized at last. Yet like all else he was subtly altered. I gasped: “Why, granddad! You’re young again! You’re younger than I am!” And in that flash I knew; and I clenched my fists and stood dumbly waiting, frozen, paralyzed, unable to speak or stir. Then something crashed against my head and with the impact a great blaze of light lighted universal darkness for an instant, and then all was oblivion.

“—Sweet William, he has died of grief,

And I shall die of sorrow!”

My grandfather’s voice still wailed in my ears, faint with the distance, as I staggered to my feet, pressing my hand to the gash the bay’s hoof had laid open in my scalp. I was sick and nauseated and my head swam dizzyingly. My grandfather was still singing. Less than seconds had elapsed since the bay’s hoof felled me senseless on the littered stable floor. Yet in those brief seconds I had travelled through the eternities and back. I knew at last my true cosmic identity, and the reason for those dreams of wooded mountains and gurgling rivers, and of a brave sweet face that had haunted my dreams since childhood.

Going out into the corral I caught the mustang and saddled him, without bothering to dress my scalp-wound. It had quit bleeding and my head was clearing. I rode down the valley and up the hill until I came to the Ormond house, perched in gaunt poverty on a sandy hill-side, limned against the brown post-oak thickets behind it. The paint on the warped boards had long ago been worn away by rain and sun, both equally fierce in the hills of the Divide.

I dismounted and entered the yard with its barbed-wire fence. Chickens pecking on the porch scampered squawking out of the way, and a gaunt hound bayed at me. The door opened to my knock and Jim Ormond stood framed in it, a gaunt, stooped man with sunken cheeks and lacklustre eyes and gnarled hands.

He looked at me in dull surprize, for we were only acquaintances.

“Is Miss Rachel—” I began. “Is she—has she—” I halted in some confusion. He shook his bushy head.

“She’s dyin’. Doc Blaine’s with her. I reckon her time’s come. She don’t want to live, noway. She keeps callin’ for Joel Grimes, pore old soul.”

“May I come in?” I asked. “I want to see Doc Blaine.” Even the dead can not intrude uninvited on the dying.

“Come in,” he drew aside and I went into the miserably bare room. A frowsy-headed woman was moving about listlessly, and cotton-headed children looked timidly at me from other doorways. Doc Blaine came out from an inner room and stared at me.

“What the devil are you doing here?”

The Ormonds had lost interest in me. They went wearily about their tasks. I came close to Doc Blaine and said in a low voice: “Rachel! I must see her!” He stared at the insistence of my tone; but he is a man who instinctively grasps sometimes things that his conscious mind does not understand.

He led me into a room and I saw an old, old woman lying on a bed. Even in her old age her vitality was apparent, though that was waning fast. She lent a new atmosphere even to the miserable surroundings. And I knew her and stood transfixed. Yes, I knew her, beyond all the years and the changes they had wrought.

She stirred and murmured: “Joel! Joel! I’ve waited for you so long! I knew you’d come.” She stretched out withered arms, and I went without a word and seated myself beside her bed. Recognition came into her glazing eyes. Her bony fingers closed on mine caressingly, and her touch was that of a young girl.

“I knew you’d come before I died,” she whispered. “Death couldn’t keep you away. Oh, the cruel wound on your head, Joel! But you’re past suffering, just as I’ll be in a few minutes. You never forgot me, Joel?”

“I never forgot you, Rachel,” I answered, and I felt Doc Blaine’s start behind me, and knew that my voice was not that of the John Grimes he knew, but another, different voice, whispering down the ages. I did not see him go, but I knew he tip-toed out.

“Sing to me, Joel,” she whispered. “There’s your guitar hanging on the wall. I’ve kept it always. Sing the song you sang when we met that day beside the Cumberland River. I always loved it.”

I took up the ancient guitar, and though I never played one before, I had no doubts. I struck the worn strings and sang, and my voice was weird and golden. The dying woman’s hands were on my arm, and as I looked, I saw and recognized the picture I had seen in the defile of the dawn. I saw youth, and love everlasting and understanding.

“Sweet William lies in the upper churchyard,

And by his side, his lover,

And on his grave grew a lily-white rose,

And on hers grew a briar.

They grew, they grew to the church-steeple-top,

And there they grew no higher,

They tied themselves in a true lover’s knot,

And there remained for ever.”

The string snapped loudly. Rachel Ormond was lying still and her lips were smiling. I disengaged my arm gently from her dead fingers and went out. Doc Blaine met me at the door.

“Dead?”

“She died years ago,” I said heavily. “She waited long for him; now she must wait somewhere else. That’s the hell of war; it upsets the balance of things and throws lives into confusion that eternity can not make right.”