Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

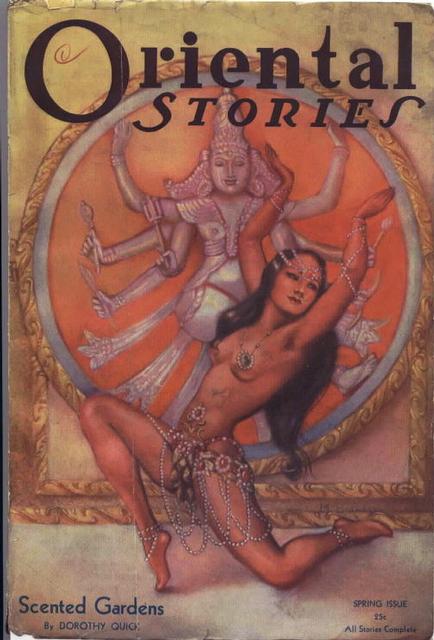

Published in Oriental Stories, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring 1932).

| Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 |

Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 |

Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 |

The roar of battle had died away; the sun hung like a ball of crimson gold on the western hills. Across the trampled field of battle no squadrons thundered, no war-cry reverberated. Only the shrieks of the wounded and the moans of the dying rose to the circling vultures whose black wings swept closer and closer until they brushed the pallid faces in their flight.

On his rangy stallion, in a hillside thicket, Ak Boga the Tatar watched, as he had watched since dawn, when the mailed hosts of the Franks, with their forest of lances and flaming pennons, had moved out on the plains of Nicopolis to meet the grim hordes of Bayazid.

Ak Boga, watching their battle array, had chk-chk’d his teeth in surprize and disapproval as he saw the glittering squadrons of mounted knights draw out in front of the compact masses of stalwart infantry, and lead the advance. They were the flower of Europe—cavaliers of Austria, Germany, France and Italy; but Ak Boga shook his head.

He had seen the knights charge with a thunderous roar that shook the heavens, had seen them smite the outriders of Bayazid like a withering blast and sweep up the long slope in the teeth of a raking fire from the Turkish archers at the crest. He had seen them cut down the archers like ripe corn, and launch their whole power against the oncoming spahis, the Turkish light cavalry. And he had seen the spahis buckle and break and scatter like spray before a storm, the light-armed riders flinging aside their lances and spurring like mad out of the melee. But Ak Boga had looked back, where, far behind, the sturdy Hungarian pikemen toiled, seeking to keep within supporting distance of the headlong cavaliers.

He had seen the Frankish horsemen sweep on, reckless of their horses’ strength as of their own lives, and cross the ridge. From his vantage-point Ak Boga could see both sides of that ridge and he knew that there lay the main power of the Turkish army—sixty-five thousand strong—the janizaries, the terrible Ottoman infantry, supported by the heavy cavalry, tall men in strong armor, bearing spears and powerful bows.

And now the Franks realized, what Ak Boga had known, that the real battle lay before them; and their horses were weary, their lances broken, their throats choked with dust and thirst.

Ak Boga had seen them waver and look back for the Hungarian infantry; but it was out of sight over the ridge, and in desperation the knights hurled themselves on the massed enemy, striving to break the ranks by sheer ferocity. That charge never reached the grim lines. Instead a storm of arrows broke the Christian front, and this time, on exhausted horses, there was no riding against it. The whole first rank went down, horses and men pincushioned, and in that red shambles their comrades behind them stumbled and fell headlong. And then the janizaries charged with a deep-toned roar of “Allah!” that was like the thunder of deep surf.

All this Ak Boga had seen; had seen, too, the inglorious flight of some of the knights, the ferocious resistance of others. On foot, leaguered and outnumbered, they fought with sword and ax, falling one by one, while the tide of battle flowed around them on either side and the blood-drunken Turks fell upon the infantry which had just toiled into sight over the ridge.

There, too, was disaster. Flying knights thundered through the ranks of the Wallachians, and these broke and retired in ragged disorder. The Hungarians and Bavarians received the brunt of the Turkish onslaught, staggered and fell back stubbornly, contesting every foot, but unable to check the victorious flood of Moslem fury.

And now, as Ak Boga scanned the field, he no longer saw the serried lines of the pikemen and ax-fighters. They had fought their way back over the ridge and were in full, though ordered, retreat, and the Turks had come back to loot the dead and mutilate the dying. Such knights as had not fallen or broken away in flight, had flung down the hopeless sword and surrendered. Among the trees on the farther side of the vale, the main Turkish host was clustered, and even Ak Boga shivered a trifle at the screams which rose where Bayazid’s swordsmen were butchering the captives. Nearer at hand ran ghoulish figures, swift and furtive, pausing briefly over each heap of corpses; here and there gaunt dervishes with foam on their beards and madness in their eyes plied their knives on writhing victims who screamed for death.

“Erlik!“ muttered Ak Boga. “They boasted that they could hold up the sky on their lances, were it to fall, and lo, the sky has fallen and their host is meat for the ravens!”

He reined his horse away through the thicket; there might be good plunder among the plumed and corseleted dead, but Ak Boga had come hither on a mission which was yet to be completed. But even as he emerged from the thicket, he saw a prize no Tatar could forego—a tall Turkish steed with an ornate high-peaked Turkish saddle came racing by. Ak Boga spurred quickly forward and caught the flying, silver-worked rein. Then, leading the restive charger, he trotted swiftly down the slope away from the battlefield.

Suddenly he reined in among a clump of stunted trees. The hurricane of strife, slaughter and pursuit had cast its spray on this side of the ridge. Before him Ak Boga saw a tall, richly clad knight grunting and cursing as he sought to hobble along using his broken lance as a crutch. His helmet was gone, revealing a blond head and a florid choleric face. Not far away lay a dead horse, an arrow protruding from its ribs.

As Ak Boga watched, the big knight stumbled and fell with a scorching oath. Then from the bushes came a man such as Ak Boga had never seen before, even among the Franks. This man was taller than Ak Boga, who was a big man, and his stride was like that of a gaunt gray wolf. He was bareheaded, a tousled shock of tawny hair topping a sinister scarred face, burnt dark by the sun, and his eyes were cold as gray icy steel. The great sword he trailed was crimson to the hilt, his rusty scale-mail shirt hacked and rent, the kilt beneath it torn and slashed. His right arm was stained to the elbow, and blood dripped sluggishly from a deep gash in his left forearm.

“Devil take all!” growled the crippled knight in Norman French, which Ak Boga understood; “this is the end of the world!”

“Only the end of a horde of fools,” the tall Frank’s voice was hard and cold, like the rasp of a sword in its scabbard.

The lame man swore again. “Stand not there like a blockhead, fool! Catch me a horse! My damnable steed caught a shaft in its cursed hide, and though I spurred it until the blood spurted over my heels, it fell at last, and I think, broke my ankle.”

The tall one dropped his sword-point to the earth and stared at the other somberly.

“You give commands as though you sat in your own fief of Saxony, Lord Baron Frederik! But for you and divers other fools, we had cracked Bayazid like a nut this day.”

“Dog!” roared the baron, his intolerant face purpling; “this insolence to me? I’ll have you flayed alive!”

“Who but you cried down the Elector in council?” snarled the other, his eyes glittering dangerously. “Who called Sigismund of Hungary a fool because he urged that the lord allow him to lead the assault with his infantry? And who but you had the ear of that young fool High Constable of France, Philip of Artois, so that in the end he led the charge that ruined us all, nor would wait on the ridge for support from the Hungarians? And now you, who turned tail quicker than any when you saw what your folly had done, you bid me fetch you a horse!”

“Aye, and quickly, you Scottish dog!” screamed the baron, convulsed with fury. “You shall answer for this—”

“I’ll answer here,” growled the Scotsman, his manner changing murderously. “You have heaped insults on me since we first sighted the Danube. If I’m to die, I’ll settle one score first!”

“Traitor!” bellowed the baron, whitening, scrambling up on his knee and reaching for his sword. But even as he did so, the Scotsman struck, with an oath, and the baron’s roar was cut short in a ghastly gurgle as the great blade sheared through shoulder-bone, ribs and spine, casting the mangled corpse limply upon the blood-soaked earth.

“Well struck, warrior!” At the sound of the guttural voice the slayer wheeled like a great wolf, wrenching free the sword. For a tense moment the two eyed each other, the swordsman standing above his victim, a brooding somber figure terrible with potentialities of blood and slaughter, the Tatar sitting his high-peaked saddle like a carven image.

“I am no Turk,” said Ak Boga. “You have no quarrel with me. See, my scimitar is in its sheath. I have need of a man like you—strong as a bear, swift as a wolf, cruel as a falcon. I can bring you to much you desire.”

“I desire only vengeance on the head of Bayazid,” rumbled the Scotsman.

The dark eyes of the Tatar glittered.

“Then come with me. For my lord is the sworn enemy of the Turk.”

“Who is your lord?” asked the Scotsman suspiciously.

“Men call him the Lame,” answered Ak Boga. “Timour, the Servant of God, by the favor of Allah, Amir of Tatary.”

The Scotsman turned his head in the direction of the distant shrieks which told that the massacre was still continuing, and stood for an instant like a great bronze statue. Then he sheathed his sword with a savage rasp of steel.

“I will go,” he said briefly.

The Tatar grinned with pleasure, and leaning forward, gave into his hands the reins of the Turkish horse. The Frank swung into the saddle and glanced inquiringly at Ak Boga. The Tatar motioned with his helmeted head and reined away down the slope. They touched in the spurs and cantered swiftly away into the gathering twilight, while behind them the shrieks of dire agony still rose to the shivering stars which peered palely out, as if frightened by man’s slaughter of man.

“Had we twa been upon the green.

And never an eye to see.

I wad hae had you, flesh and fell;

But your sword shall gae wi’ me.”

—The Ballad of Otterbourne.

Again the sun was sinking, this time over a desert, etching the spires and minarets of a blue city. Ak Boga drew rein on the crest of a rise and sat motionless for a moment, sighing deeply as he drank in the familiar sight, whose wonder never faded.

“Samarcand,” said Ak Boga.

“We have ridden far,” answered his companion. Ak Boga smiled. The Tatar’s garments were dusty, his mail tarnished, his face somewhat drawn, though his eyes still twinkled. The Scotsman’s strongly chiseled features had not altered.

“You are of steel, bogatyr,” said Ak Boga. “The road we have traveled would have wearied a courier of Genghis Khan. And by Erlik, I, who was bred in the saddle, am the wearier of the twain!”

The Scotsman gazed unspeaking at the distant spires, remembering the days and nights of apparently endless riding, when he had slept swaying in the saddle, and all the sounds of the universe had died down to the thunder of hoofs. He had followed Ak Boga unquestioning: through hostile hills where they avoided trails and cut through the blind wilderness, over mountains where the chill winds cut like a sword-edge, into stretches of steppes and desert. He had not questioned when Ak Boga’s relaxing vigilance told him that they were out of hostile country, and when the Tatar began to stop at wayside posts where tall dark men in iron helmets brought fresh steeds. Even then there was no slacking of the headlong pace: a swift guzzling of wine and snatching of food; occasionally a brief interlude of sleep, on a heap of hides and cloaks; then again the drum of racing hoofs. The Frank knew that Ak Boga was bearing the news of the battle to his mysterious lord, and he wondered at the distance they had covered between the first post where saddled steeds awaited them and the blue spires that marked their journey’s end. Wide-flung indeed were the boundaries of the lord called Timour the Lame.

They had covered that vast expanse of country in a time the Frank would have sworn impossible. He felt now the grinding wear of that terrible ride, but he gave no outward sign. The city shimmered to his gaze, mingling with the blue of the distance, so that it seemed part of the horizon, a city of illusion and enchantment. Blue: the Tatars lived in a wide magnificent land, lavish with color schemes, and the prevailing motif was blue. In the spires and domes of Samarcand were mirrored the hues of the skies, the far mountains and the dreaming lakes.

“You have seen lands and seas no Frank has beheld,” said Ak Boga, “and rivers and towns and caravan trails. Now you shall gaze upon the glory of Samarcand, which the lord Timour found a town of dried brick and has made a metropolis of blue stone and ivory and marble and silver filigree.”

The two descended into the plain and threaded their way between converging lines of camel-caravans and mule-trains whose robed drivers shouted incessantly, all bound for the Turquoise Gates, laden with spices, silks, jewels, and slaves, the goods and gauds of India and Cathay, of Persia and Arabia and Egypt.

“All the East rides the road to Samarcand,” said Ak Boga.

They passed through the wide gilt-inlaid gates where the tall spearmen shouted boisterous greetings to Ak Boga, who yelled back, rolling in his saddle and smiting his mailed thigh with the joy of homecoming. They rode through the wide winding streets, past palace and market and mosque, and bazaars thronged with the people of a hundred tribes and races, bartering, disputing, shouting. The Scotsman saw hawk-faced Arabs, lean apprehensive Syrians, fat fawning Jews, turbaned Indians, languid Persians, ragged swaggering but suspicious Afghans, and more unfamiliar forms; figures from the mysterious reaches of the north, and the far east; stocky Mongols with broad inscrutable faces and the rolling gait of an existence spent in the saddle; slant-eyed Cathayans in robes of watered silk; tall quarrelsome Vigurs; round-faced Kipchaks; narrow-eyed Kirghiz; a score of races whose existence the West did not guess. All the Orient flowed in a broad river through the gates of Samarcand.

The Frank’s wonder grew; the cities of the West were hovels compared to this. Past academies, libraries and pleasure-pavilions they rode, and Ak Boga turned into a wide gateway, guarded by silver lions. There they gave their steeds into the hands of silk-sashed grooms, and walked along a winding avenue paved with marble and lined with slim green trees. The Scotsman, looking between the slender trunks, saw shimmering expanses of roses, cherry trees and waving exotic blossoms unknown to him, where fountains jetted arches of silver spray. So they came to the palace, gleaming blue and gold in the sunlight, passed between tall marble columns and entered the chambers with their gilt-worked arched doorways, and walls decorated with delicate paintings of Persian and Cathayan artists, and the gold tissue and silver work of Indian artistry.

Ak Boga did not halt in the great reception room with its slender carven columns and frieze-work of gold and turquoise, but continued until he came to the fretted gold-adorned arch of a door which opened into a small blue-domed chamber that looked out through gold-barred windows into a series of broad, shaded, marble-paved galleries. There silk-robed courtiers took their weapons, and grasping their arms, led them between files of giant black mutes in silken loincloths, who held two-handed scimitars upon their shoulders, and into the chamber, where the courtiers released their arms and fell back, salaaming deeply. Ak Boga knelt before the figure on the silken divan, but the Scotsman stood grimly erect, nor was obeisance required of him. Some of the simplicity of Genghis Khan’s court still lingered in the courts of these descendants of the nomads.

The Scotsman looked closely at the man on the divan; this, then, was the mysterious Tamerlane, who was already becoming a mythical figure in Western lore. He saw a man as tall as himself, gaunt but heavy-boned, with a wide sweep of shoulders and the Tatar’s characteristic depth of chest. His face was not as dark as Ak Boga’s, nor did his black magnetic eyes slant; and he did not sit cross-legged as a Mongol sits. There was power in every line of his figure, in his clean-cut features, in the crisp black hair and beard, untouched with gray despite his sixty-one years. There was something of the Turk in his appearance, thought the Scotsman, but the dominant note was the lean wolfish hardness that suggested the nomad. He was closer to the basic Turanian rootstock than was the Turk; nearer to the wolfish, wandering Mongols who were his ancestors.

“Speak, Ak Boga,” said the Amir in a deep powerful voice. “Ravens have flown westward, but there has come no word.”

“We rode before the word, my lord,” answered the warrior. “The news is at our heels, traveling swift on the caravan roads. Soon the couriers, and after them the traders and the merchants, will bring to you the news that a great battle has been fought in the west; that Bayazid has broken the hosts of the Christians, and the wolves howl over the corpses of the kings of Frankistan.”

“And who stands beside you?” asked Timour, resting his chin on his hand and fixing his deep somber eyes on the Scotsman.

“A chief of the Franks who escaped the slaughter,” answered Ak Boga. “Single-handed he cut his way through the melee, and in his flight paused to slay a Frankish lord who had put shame upon him aforetime. He has no fear and his thews are steel. By Allah, we passed through the land outracing the wind to bring thee news of the war, and this Frank is less weary than I, who learned to ride ere I learned to walk.”

“Why do you bring him to me?”

“It was my thought that he would make a mighty warrior for thee, my lord.”

“In all the world,” mused Timour, “there are scarce half a dozen men whose judgment I trust. Thou art one of those,” he added briefly, and Ak Boga, who had flushed darkly in embarrassment, grinned delightedly.

“Can he understand me?” asked Timour.

“He speaks Turki, my lord.”

“How are you named, oh Frank?” queried the Amir. “And what is your rank?”

“I am called Donald MacDeesa,” answered the Scotsman. “I come from the country of Scotland, beyond Frankistan. I have no rank, either in my own land or in the army I followed. I live by my wits and the edge of my claymore.”

“Why do you ride to me?”

“Ak Boga told me it was the road to vengeance.”

“Against whom?”

“Bayazid the Sultan of the Turks, whom men name the Thunderer.”

Timour dropped his head on his mighty breast for a space and in the silence MacDeesa heard the silvery tinkle of a fountain in an outer court and the musical voice of a Persian poet singing to a lute.

Then the great Tatar lifted his lion’s head.

“Sit ye with Ak Boga upon this divan close at my hand,” said he. “I will instruct you how to trap a gray wolf.”

As Donald did so, he unconsciously lifted a hand to his face, as if he felt the sting of a blow eleven years old. Irrelevantly his mind reverted to another king and another, ruder court, and in the swift instant that elapsed as he took his seat close to the Amir, glanced fleetingly along the bitter trail of his life.

Young Lord Douglas, most powerful of all the Scottish barons, was headstrong and impetuous, and like most Norman lords, choleric when he fancied himself crossed. But he should not have struck the lean young Highlander who had come down into the border country seeking fame and plunder in the train of the lords of the marches. Douglas was accustomed to using both riding-whip and fists freely on his pages and esquires, and promptly forgetting both the blow and the cause; and they, being also Normans and accustomed to the tempers of their lords, likewise forgot. But Donald MacDeesa was no Norman; he was a Gael, and Gaelic ideas of honor and insult differ from Norman ideas as the wild uplands of the North differ from the fertile plains of the Lowlands. The chief of Donald’s clan could not have struck him with impunity, and for a Southron to so venture—hate entered the young Highlander’s blood like a black river and filled his dreams with crimson nightmares.

Douglas forgot the blow too quickly to regret it. But Donald’s was the vengeful heart of those wild folk who keep the fires of feud flaming for centuries and carry grudges to the grave. Donald was as fully Celtic as his savage Dalriadian ancestors who carved out the kingdom of Alba with their swords.

But he hid his hate and bided his time, and it came in a hurricane of border war. Robert Bruce lay in his tomb, and his heart, stilled forever, lay somewhere in Spain beneath the body of Black Douglas, who had failed in the pilgrimage which was to place the heart of his king before the Holy Sepulcher. The great king’s grandson, Robert ii, had little love for storm and stress; he desired peace with England and he feared the great family of Douglas.

But despite his protests, war spread flaming wings along the border and the Scottish lords rode joyfully on the foray. But before the Douglas marched, a quiet and subtle man came to Donald MacDeesa’s tent and spoke briefly and to the point.

“Knowing that the aforesaid lord hath put despite upon thee, I whispered thy name softly to him that sendeth me, and sooth, it is well known that this same bloody lord doth continually embroil the kingdoms and stir up wrath and woe between the sovereigns—” he said in part, and he plainly spoke the word, “Protection.”

Donald made no answer and the quiet person smiled and left the young Highlander sitting with his chin on his fist, staring grimly at the floor of his tent.

Thereafter Lord Douglas marched right gleefully with his retainers into the border country and “burned the dales of Tyne, and part of Bambroughshire, and three good towers on Reidswire fells, he left them all on fire,” and spread wrath and woe generally among the border English, so that King Richard sent notes of bitter reproach to King Robert, who bit his nails with rage, but waited patiently for news he expected to hear.

Then after an indecisive skirmish at Newcastle, Douglas encamped in a place called Otterbourne, and there Lord Percy, hot with wrath, came suddenly upon him in the night, and in the confused melee which ensued, called by the Scottish the Battle of Otterbourne and by the English Chevy Chase, Lord Douglas fell. The English swore he was slain by Lord Percy, who neither confirmed nor denied it, not knowing himself what men he had slain in the confusion and darkness.

But a wounded man babbled of a Highland plaid, before he died, and an ax wielded by no English hand. Men came to Donald and questioned him hardly, but he snarled at them like a wolf, and the king, after piously burning many candles for Douglas’ soul in public, and thanking God for the baron’s demise in the privacy of his chamber, announced that “we have heard of this persecution of a loyal subject and it being plain in our mind that this youth is innocent as ourselves in this matter we hereby warn all men against further hounding of him at pain of death.”

So the king’s protection saved Donald’s life, but men muttered in their teeth and ostracized him. Sullen and embittered, he withdrew to himself and brooded in a hut alone, till one night there came news of the king’s sudden abdication and retirement into a monastery. The stress of a monarch’s life in those stormy times was too much for the monkish sovereign. Close on the heels of the news came men with drawn daggers to Donald’s hut, but they found the cage empty. The hawk had flown, and though they followed his trail with reddened spurs, they found only a steed that had fallen dead at the seashore, and saw only a white sail dwindling in the growing dawn.

Donald went to the Continent because, with the Lowlands barred to him, there was nowhere else to go; in the Highlands he had too many blood-feuds; and across the border the English had already made a noose for him. That was in 1389. Seven years of fighting and intriguing in European wars and plots. And when Constantinople cried out before the irresistible onslaught of Bayazid, and men pawned their lands to launch a new Crusade, the Highland swordsman had joined the tide that swept eastward to its doom. Seven years—and a far cry from the border marches to the blue-domed palaces of fabulous Samarcand, reclining on a silken divan as he listened to the measured words which flowed in a tranquil monotone from the lips of the lord of Tatary.

“If thou’rt the lord of this castle.

Sae well it pleases me:

For, ere I cross the border fells.

The tane of us shall dee.”

—Battle of Otterbourne.

Time flowed on as it does whether men live or die. The bodies rotted on the plains of Nicopolis, and Bayazid, drunk with power, trampled the scepters of the world. The Greeks, the Serbs and the Hungarians he ground beneath his iron legions, and into his spreading empire he molded the captive races. He laved his limbs in wild debauchery, the frenzy of which astounded even his tough vassals. The women of the world flowed whimpering between his iron fingers and he hammered the golden crowns of kings to shoe his war-steed. Constantinople reeled beneath his strokes, and Europe licked her wounds like a crippled wolf, held at bay on the defensive. Somewhere in the misty mazes of the East moved his arch-foe Timour, and to him Bayazid sent missives of threat and mockery. No response was forthcoming, but word came along the caravans of a mighty marching and a great war in the south; of the plumed helmets of India scattered and flying before the Tatar spears. Little heed gave Bayazid; India was little more real to him than it was to the Pope of Rome. His eyes were turned westward toward the Caphar cities. “I will harrow Frankistan with steel and flame,” he said. “Their sultans shall draw my chariots and the bats lair in the palaces of the infidels.”

Then in the early spring of 1402 there came to him, in an inner court of his pleasure-palace at Brusa, where he lolled guzzling the forbidden wine and watching the antics of naked dancing girls, certain of his emirs, bringing a tall Frank whose grim scarred visage was darkened by the suns of far deserts.

“This Caphar dog rode into the camp of the janizaries as a madman rides, on a foam-covered steed,” said they, “saying he sought Bayazid. Shall we flay him before thee, or tear him between wild horses?”

“Dog,” said the Sultan, drinking deeply and setting down the goblet with a satisfied sigh, “you have found Bayazid. Speak, ere I set you howling on a stake.”

“Is this fit welcome for one who has ridden far to serve you?” retorted the Frank in a harsh unshaken voice. “I am Donald MacDeesa and among your janizaries there is no man who can stand up against me in sword-play, and among your barrel-bellied wrestlers there is no man whose back I can not break.”

The Sultan tugged his black beard and grinned.

“Would thou wert not an infidel,” said he, “for I love a man with a bold tongue. Speak on, oh Rustum! What other accomplishments are thine, mirror of modesty?”

The Highlander grinned like a wolf.

“I can break the back of a Tatar and roll the head of a Khan in the dust.”

Bayazid stiffened, subtly changing, his giant frame charged with dynamic power and menace; for behind all his roistering and bellowing conceit was the keenest brain west of the Oxus.

“What folly is this?” he rumbled. “What means this riddle?”

“I speak no riddle,” snapped the Gael. “I have no more love for you than you for me. But more I hate Timour-il-leng who has cast dung in my face.”

“You come to me from that half-pagan dog?”

“Aye. I was his man. I rode beside him and cut down his foes. I climbed city walls in the teeth of the arrows and broke the ranks of mailed spearmen. And when the honors and gifts were distributed among the emirs, what was given me? The gall of mockery and the wormwood of insult. ‘Ask thy dog-sultans of Frankistan for gifts, Caphar,’ said Timour—may the worms devour him—and the emirs roared with laughter. As God is my witness, I will wipe out that laughter in the crash of falling walls and the roar of flames!”

Donald’s menacing voice reverberated through the chamber and his eyes were cold and cruel. Bayazid pulled his beard for a space and said, “And you come to me for vengeance? Shall I war against the Lame One because of the spite of a wandering Caphar vagabond?”

“You will war against him, or he against you,” answered MacDeesa. “When Timour wrote asking that you lend no aid to his foes, Kara Yussef the Turkoman, and Ahmed, Sultan of Bagdad, you answered him with words not to be borne, and sent horsemen to stiffen their ranks against him. Now the Turkomans are broken, Bagdad has been looted and Damascus lies in smoking ruins. Timour has broken your allies and he will not forget the despite you put upon him.”

“Close have you been to the Lame One to know all this,” muttered Bayazid, his glittering eyes narrowing with suspicion. “Why should I trust a Frank? By Allah, I deal with them by the sword! As I dealt with those fools at Nicopolis!”

A fierce uncontrollable flame leaped up for a fleeting instant in the Highlander’s eyes, but the dark face showed no sign of emotion.

“Know this, Turk,” he answered with an oath, “I can show you how to break Timour’s back.”

“Dog!” roared the Sultan, his gray eyes blazing, “think you I need the aid of a nameless rogue to conquer the Tatar?”

Donald laughed in his face, a hard mirthless laugh that was not pleasant.

“Timour will crack you like a walnut,” said he deliberately. “Have you seen the Tatars in war array? Have you seen their arrows darkening the sky as they loosed, a hundred thousand as one? Have you seen their horsemen flying before the wind as they charged home and the desert shook beneath their hoofs? Have you seen the array of their elephants, with towers on their backs, whence archers send shafts in black clouds and the fire that burns flesh and leather alike pours forth?”

“All this I have heard,” answered the Sultan, not particularly impressed.

“But you have not seen,” returned the Highlander; he drew back his tunic sleeve and displayed a scar on his iron-thewed arm. “An Indian tulwar kissed me there, before Delhi. I rode with the emirs when the whole world seemed to shake with the thunder of combat. I saw Timour trick the Sultan of Hindustan and draw him from the lofty walls as a serpent is drawn from its lair. By God, the plumed Rajputs fell like ripened grain before us!

“Of Delhi Timour left a pile of deserted ruins, and without the broken walls he built a pyramid of a hundred thousand skulls. You would say I lied were I to tell you how many days the Khyber Pass was thronged with the glittering hosts of warriors and captives returning along the road to Samarcand. The mountains shook with their tread and the wild Afghans came down in hordes to place their heads beneath Timour’s heel—as he will grind thy head underfoot, Bayazid!”

“This to me, dog?” yelled the Sultan. “I will fry you in oil!”

“Aye, prove your power over Timour by slaying the dog he mocked,” answered MacDeesa bitterly. “You kings are all alike in fear and folly.”

Bayazid gaped at him. “By Allah!” he said, “thou’rt mad to speak thus to the Thunderer. Bide in my court until I learn whether thou be rogue, fool, or madman. If spy, not in a day or three days will I slay thee, but for a full week shalt thou howl for death.”

So Donald abode in the court of the Thunderer, under suspicion, and soon there came a brief but peremptory note from Timour, asking that “the thief of a Christian who hath taken refuge in the Ottoman court” be given up for just punishment. Whereat Bayazid, scenting an opportunity to further insult his rival, twisted his black beard gleefully between his fingers and grinned like a hyena as he dictated a reply, “Know, thou crippled dog, that the Osmanli are not in the habit of conceding to the insolent demands of pagan foes. Be at ease while thou mayest, oh lame dog, for soon I will take thy kingdom for an offal-heap and thy favorite wives for my concubines.”

No further missives came from Timour. Bayazid drew Donald into wild revels, plied him with strong drink and even as he roared and roistered, he keenly watched the Highlander. But even his suspicions grew blunter when at his drunkest Donald spoke no word that might hint he was other than he seemed. He breathed the name of Timour only with curses. Bayazid discounted the value of his aid against the Tatars, but contemplated putting him to use, as Ottoman sultans always employed foreigners for confidants and guardsmen, knowing their own race too well. Under close, subtle scrutiny the Gael indifferently moved, drinking all but the Sultan onto the floor in the wild drinking-bouts and bearing himself with a reckless valor that earned the respect of the hard-bitten Turks, in forays against the Byzantines.

Playing Genoese against Venetian, Bayazid lay about the walls of Constantinople. His preparations were made: Constantinople, and after that, Europe; the fate of Christendom wavered in the balance, there before the walls of the ancient city of the East. And the wretched Greeks, worn and starved, had already drawn up a capitulation, when word came flying out of the East, a dusty, bloodstained courier on a staggering horse. Out of the East, sudden as a desert-storm, the Tatars had swept, and Sivas, Bayazid’s border city, had fallen. That night the shuddering people on the walls of Constantinople saw torches and cressets tossing and moving through the Turkish camp, gleaming on dark hawk-faces and polished armor, but the expected attack did not come, and dawn revealed a great flotilla of boats moving in a steady double stream back and forth across the Bosphorus, bearing the mailed warriors into Asia. The Thunderer’s eyes were at last turned eastward.

“The deer runs wild on hill and dale.

The birds fly wild from tree to tree;

But there is neither bread nor kale.

To fend my men and me.”

—Battle of Otterbourne.

“Here we will camp,” said Bayazid, shifting his giant body in the gold-crusted saddle. He glanced back at the long lines of his army, winding beyond sight over the distant hills: over 200,000 fighting men; grim janizaries, spahis glittering in plumes and silver mail, heavy cavalry in silk and steel; and his allies and alien subjects, Greek and Wallachian pikemen, the twenty thousand horsemen of King Peter Lazarus of Serbia, mailed from crown to heel; there were troops of Tatars, too, who had wandered into Asia Minor and been ground into the Ottoman empire with the rest—stocky Kalmucks, who had been on the point of mutiny at the beginning of the march, but had been quieted by a harangue from Donald MacDeesa, in their own tongue.

For weeks the Turkish host had moved eastward on the Sivas road, expecting to encounter the Tatars at any point. They had passed Angora, where the Sultan had established his base-camp; they had crossed the river Halys, or Kizil Irmak, and now were marching through the hill country that lies in the bend of that river which, rising east of Sivas, sweeps southward in a vast half-circle before it bends, west of Kirshehr, northward to the Black Sea.

“Here we camp,” repeated Bayazid; “Sivas lies some sixty-five miles to the east. We will send scouts into the city.”

“They will find it deserted,” predicted Donald, riding at Bayazid’s side, and the Sultan scoffed, “Oh gem of wisdom, will the Lame One flee so quickly?”

“He will not flee,” answered the Gael. “Remember he can move his host far more quickly than you can. He will take to the hills and fall suddenly upon us when you least expect it.”

Bayazid snorted his contempt. “Is he a magician, to flit among the hills with a horde of 150,000 men? Bah! I tell you, he will come along the Sivas road to join battle, and we will crack him like a nutshell.”

So the Turkish host went into camp and fortified the hills, and there they waited with growing wrath and impatience for a week. Bayazid’s scouts returned with the news that only a handful of Tatars held Sivas. The Sultan roared with rage and bewilderment.

“Fools, have ye passed the Tatars on the road?”

“Nay, by Allah,” swore the riders, “they vanished in the night like ghosts, none can say whither. And we have combed the hills between this spot and the city.”

“Timour has fled back to his desert,” said Peter Lazarus, and Donald laughed.

“When rivers run uphill, Timour will flee,” said he; “he lurks somewhere in the hills to the south.”

Bayazid had never taken other men’s advice, for he had found long ago that his own wit was superior. But now he was puzzled. He had never before fought the desert riders whose secret of victory was mobility and who passed through the land like blown clouds. Then his outriders brought in word that bodies of mounted men had been seen moving parallel to the Turkish right wing.

MacDeesa laughed like a jackal barking. “Now Timour sweeps upon us from the south, as I predicted.”

Bayazid drew up his lines and waited for the assault, but it did not come and his scouts reported that the riders had passed on and disappeared. Bewildered for the first time in his career, and mad to come to grips with his illusive foe, Bayazid struck camp and on a forced march reached the Halys river in two days, where he expected to find Timour drawn up to dispute his passage. No Tatar was to be seen. The Sultan cursed in his black beard; were these eastern devils ghosts, to vanish in thin air? He sent riders across the river and they came flying back, splashing recklessly through the shallow water. They had seen the Tatar rear guard. Timour had eluded the whole Turkish army, and was even now marching on Angora! Frothing, Bayazid turned on MacDeesa.

“Dog, what have you to say now?”

“What would you?” the Highlander stood his ground boldly. “You have none but yourself to blame, if Timour has outwitted you. Have you harkened to me in aught, good or bad? I told you Timour would not await your coming, nor did he. I told you he would leave the city and go into the southern hills. And he did. I told you he would fall upon us suddenly, and therein I was mistaken. I did not guess that he would cross the river and elude us. But all else I warned you of has come to pass.”

Bayazid grudgingly admitted the truth of the Frank’s words, but he was mad with fury. Else he had never sought to overtake the swift-moving horde before it reached Angora. He flung his columns across the river and started on the track of the Tatars. Timour had crossed the river near Sivas, and moving around the outer bend, eluded the Turks on the other side. And now Bayazid followed his road, which swung outward from the river, into the plains where there was little water—and no food, after the horde had swept through with torch and blade.

The Turks marched over a fire-blackened, slaughter-reddened waste. Timour covered the ground in three days, over which Bayazid’s columns staggered in a week of forced marching; a hundred miles through the burning, desolated plain, strewn with bare hills that made marching a hell. As the strength of the army lay in its infantry, the cavalry was forced to set its pace with the foot-soldiers, and all stumbled wearily through the clouds of stinging dust that rose from beneath the sore, shuffling feet. Under a burning summer sun they plodded grimly along, suffering fiercely from hunger and thirst.

So they came at last to the plain of Angora, and saw the Tatars installed in the camp they had left, besieging the city. And a roar of desperation went up from the thirst-maddened Turks. Timour had changed the course of the little river which ran through Angora, so that now it ran behind the Tatar lines; the only way to reach it was straight through the desert hordes. The springs and wells of the countryside had been polluted or damaged. For an instant Bayazid sat silent in his saddle, gazing from the Tatar camp to his own long straggling lines, and the marks of suffering and vain wrath in the drawn faces of his warriors. A strange fear tugged at his heart, so unfamiliar he did not recognize the emotion. Victory had always been his; could it ever be otherwise?

“What’s yon that follows at my side?—

The foe that ye must fight, my lord,—

That hirples swift as I can ride?—

The shadow of the night, my lord.”

—Kipling.

On that still summer morning the battle-lines stood ready for the death-grip. The Turks were drawn up in a long crescent, whose tips overlapped the Tatar wings, one of which touched the river and the other an entrenched hill fifteen miles away across the plain.

“Never in all my life have I sought another’s advice in war,” said Bayazid, “but you rode with Timour six years. Will he come to me?”

Donald shook his head. “You outnumber his host. He will never fling his riders against the solid ranks of your janizaries. He will stand afar off and overwhelm you with flights of arrows. You must go to him.”

“Can I charge his horse with my infantry?” snarled Bayazid. “Yet you speak wise words. I must hurl my horse against his—and Allah knows his is the better cavalry.”

“His right wing is the weaker,” said Donald, a sinister light burning in his eyes. “Mass your strongest horsemen on your left wing, charge and shatter that part of the Tatar host; then let your left wing close in, assailing the main battle of the Amir on the flank, while your janizaries advance from the front. Before the charge the spahis on your right wing may make a feint at the lines, to draw Timour’s attention.”

Bayazid looked silently at the Gael. Donald had suffered as much as the rest on that fearful march. His mail was white with dust, his lips blackened, his throat caked with thirst.

“So let it be,” said Bayazid. “Prince Suleiman shall command the left wing, with the Serbian horse and my own heavy cavalry, supported by the Kalmucks. We will stake all on one charge!”

And so they took up their positions, and no one noticed a flat-faced Kalmuck steal out of the Turkish lines and ride for Timour’s camp, flogging his stocky pony like mad. On the left wing was massed the powerful Serbian cavalry and the Turkish heavy horse, with the bow-armed Kalmucks behind. At the head of these rode Donald, for they had clamored for the Frank to lead them against their kin. Bayazid did not intend to match bow-fire with the Tatars, but to drive home a charge that would shatter Timour’s lines before the Amir could further outmaneuver him. The Turkish right wing consisted of the spahis; the center of the janizaries and Serbian foot with Peter Lazarus, under the personal command of the Sultan.

Timour had no infantry. He sat with his bodyguard on a hillock behind the lines. Nur ad-Din commanded the right wing of the riders of high Asia, Ak Boga the left, Prince Muhammad the center. With the center were the elephants in their leather trappings, with their battle-towers and archers. Their awesome trumpeting was the only sound along the widespread steel-clad Tatar lines as the Turks came on with a thunder of cymbals and kettle-drums.

Like a thunderbolt Suleiman launched his squadrons at the Tatar right wing. They ran full into a terrible blast of arrows, but grimly they swept on, and the Tatar ranks reeled to the shock. Suleiman, cutting a heron-plumed chieftain out of his saddle, shouted in exultation, but even as he did so, behind him rose a guttural roar, “Ghar! ghar! ghar! Smite, brothers, for the lord Timour!”

With a sob of rage he turned and saw his horsemen going down in windrows beneath the arrows of the Kalmucks. And in his ear he heard Donald MacDeesa laughing like a madman.

“Traitor!” screamed the Turk. “This is your work—”

The claymore flashed in the sun and Prince Suleiman rolled headless from his saddle.

“One stroke for Nicopolis!” yelled the maddened Highlander. "Drive home your shafts, dog-brothers!”

The stocky Kalmucks yelped like wolves in reply, wheeling away to avoid the scimitars of the desperate Turks, and driving their deadly arrows into the milling ranks at close range. They had endured much from their masters; now was the hour of reckoning. And now the Tatar right wing drove home with a roar; and caught before and behind, the Turkish cavalry buckled and crumpled, whole troops breaking away in headlong flight. At one stroke had been swept away Bayazid’s chance to crush his enemy’s formation.

As the charge had begun, the Turkish right wing had advanced with a great blare of trumpets and roll of drums, and in the midst of its feint, had been caught by the sudden unexpected charge of the Tatar left. Ak Boga had swept through the light spahis, and losing his head momentarily in the lust of slaughter, he drove them flying before him until pursued and pursuers vanished over the slopes in the distance.

Timour sent Prince Muhammad with a reserve squadron to support the left wing and bring it back, while Nur ad-Din, sweeping aside the remnants of Bayazid’s cavalry, swung in a pivot-like movement and thundered against the locked ranks of the janizaries. They held like a wall of iron, and Ak Boga, galloping back from his pursuit of the spahis, smote them on the other flank. And now Timour himself mounted his war-steed, and the center rolled like an iron wave against the staggering Turks. And now the real death-grip came to be.

Charge after charge crashed on those serried ranks, surging on and rolling back like onsweeping and receding waves. In clouds of fire-shot dust the janizaries stood unshaken, thrusting with reddened spears, smiting with dripping ax and notched scimitar. The wild riders swept in like blasting whirlwinds, raking the ranks with the storms of their arrows as they drew and loosed too swiftly for the eye to follow, rushing headlong into the press, screaming and hacking like madmen as their scimitars sheared through buckler, helmet and skull. And the Turks beat them back, overthrowing horse and rider; hacked them down and trampled them under, treading their own dead under foot to close the ranks, until both hosts trod on a carpet of the slain and the hoofs of the Tatar steeds splashed blood at every leap.

Repeated charges tore the Turkish host apart at last, and all over the plain the fight raged on, where clumps of spearmen stood back to back, slaying and dying beneath the arrows and scimitars of the riders from the steppes. Through the clouds of rising dust stalked the elephants trumpeting like Doom, while the archers on their backs rained down blasts of arrows and sheets of fire that withered men in their mail like burnt grain.

All day Bayazid had fought grimly on foot at the head of his men. At his side fell King Peter, pierced by a score of arrows. With a thousand of his janizaries the Sultan held the highest hill upon the plain, and through the blazing hell of that long afternoon he held it still, while his men died beside him. In a hurricane of splintering spears, lashing axes and ripping scimitars, the Sultan’s warriors held the victorious Tatars to a gasping deadlock. And then Donald MacDeesa, on foot, eyes glaring like a mad dog’s, rushed headlong through the melee and smote the Sultan with such hate-driven fury that the crested helmet shattered beneath the claymore’s whistling edge and Bayazid fell like a dead man. And over the weary groups of bloodstained defenders rolled the dark tide, and the kettle drums of the Tatars thundered victory.

“The searing glory which hath shone

Amid the jewels of my throne.

Halo of Hell! and with a pain

Not Hell shall make me fear again.”

—Poe, Tamerlane.

The power of the Osmanli was broken, the heads of the emirs heaped before Timour’s tent. But the Tatars swept on; at the heels of the flying Turks they burst into Brusa, Bayazid’s capital, sweeping the streets with sword and flame. Like a whirlwind they came and like a whirlwind they went, laden with treasures of the palace and the women of the vanished Sultan’s seraglio.

Riding back to the Tatar camp beside Nur ad-Din and Ak Boga, Donald MacDeesa learned that Bayazid lived. The stroke which had felled him had only stunned, and the Turk was captive to the Amir he had mocked. MacDeesa cursed; the Gael was dusty and stained with hard riding and harder fighting; dried blood darkened his mail and clotted his scabbard mouth. A red-soaked scarf was bound about his thigh as a rude bandage; his eyes were bloodshot, his thin lips frozen in a snarl of battle-fury.

“By God, I had not thought a bullock could survive that blow. Is he to be crucified—as he swore to deal with Timour thus?”

“Timour gave him good welcome and will do him no hurt,” answered the courtier who brought the news. “The Sultan will sit at the feast.”

Ak Boga shook his head, for he was merciful except in the rush of battle, but in Donald’s ears were ringing the screams of the butchered captives at Nicopolis, and he laughed shortly—a laugh that was not pleasant to hear.

To the fierce heart of the Sultan, death was easier than sitting a captive at the feast which always followed a Tatar victory. Bayazid sat like a grim image, neither speaking nor seeming to hear the crash of the kettle-drums, the roar of barbaric revelry. On his head was the jeweled turban of sovereignty, in his hand the gem-starred scepter of his vanished empire.

He did not touch the great golden goblet before him. Many and many a time had he exulted over the agony of the vanquished, with much less mercy than was now shown him; now the unfamiliar bite of defeat left him frozen.

He stared at the beauties of his seraglio, who, according to Tatar custom, tremblingly served their new masters: black-haired Jewesses with slumberous, heavy-lidded eyes; lithe tawny Circassians and golden-haired Russians; dark-eyed Greek girls and Turkish women with figures like Juno—all naked as the day they were born, under the burning eyes of the Tatar lords.

He had sworn to ravish Timour’s wives—the Sultan writhed as he saw the Despina, sister of Peter Lazarus and his favorite, nude like the rest, kneel and in quivering fear offer Timour a goblet of wine. The Tatar absently wove his fingers in her golden locks and Bayazid shuddered as if those fingers were locked in his own heart.

And he saw Donald MacDeesa sitting next to Timour, his stained dusty garments contrasting strangely with the silk-and-gold splendor of the Tatar lords—his savage eyes ablaze, his dark face wilder and more passionate than ever as he ate like a ravenous wolf and drained goblet after goblet of stinging wine. And Bayazid’s iron control snapped. With a roar that struck the clamor dumb, the Thunderer lurched upright, breaking the heavy scepter like a twig between his hands and dashing the fragments to the floor.

All eyes turned toward him and some of the Tatars stepped quickly between him and their Amir, who only looked at him impassively.

“Dog and spawn of a dog!” roared Bayazid. “You came to me as one in need and I sheltered you! The curse of all traitors rest on your black heart!”

MacDeesa heaved up, scattered goblets and bowls.

“Traitors?” he yelled. “Is six years so long you forget the headless corpses that molder at Nicopolis? Have you forgotten the ten thousand captives you slew there, naked and with their hands bound? I fought you there with steel; and since I have fought you with guile! Fool, from the hour you marched from Brusa, you were doomed! It was I who spoke softly to the Kalmucks, who hated you; so they were content and seemed willing to serve you. With them I communicated with Timour from the time we first left Angora—sending riders forth secretly or feigning to hunt for antelopes.

“Through me, Timour tricked you—even put into your head the plan of your battle! I caught you in a web of truths, knowing that you would follow your own course, regardless of what I or any one else said. I told you but two lies—when I said I sought revenge on Timour, and when I said the Amir would bide in the hills and fall upon us. Before battle joined I knew what Timour wished, and by my advice led you into a trap. So Timour, who had drawn out the plan you thought part yours and part mine, knew beforehand every move you would make. But in the end, it hinged on me, for it was I who turned the Kalmucks against you, and their arrows in the backs of your horsemen which tipped the scales when the battle hung in the balance.

“I paid high for my vengeance, Turk! I played my part under the eyes of your spies, in your court, every instant, even when my head was reeling with wine. I fought for you against the Greeks and took wounds. In the wilderness beyond the Halys I suffered with the rest. And I would have gone through greater hells to bring you to the dust!”

“Serve well your master as you have served me, traitor,” retorted the Sultan. “In the end, Timour-il-leng, you will rue the day you took this adder into your naked hands. Aye, may each of you bring the other down to death!”

“Be at ease, Bayazid,” said Timour impassively. “What is written, is written.”

“Aye!” answered the Turk with a terrible laugh. “And it is not written that the Thunderer should live a buffoon for a crippled dog! Lame One, Bayazid gives you—hail and farewell!”

And before any could stay him, the Sultan snatched a carving-knife from a table and plunged it to the hilt in his throat. A moment he reeled like a mighty tree, spurting blood, and then crashed thunderously down. All noise was hushed as the multitude stood aghast. A pitiful cry rang out as the young Despina ran forward, and dropping to her knees, drew the lion’s head of her grim lord to her naked bosom, sobbing convulsively. But Timour stroked his beard measuredly and half-abstractedly. And Donald MacDeesa, seating himself, took up a great goblet that glowed crimson in the torchlight, and drank deeply.

“Hath not the same fierce heirdom given

Rome to the Caesar—this to me?”

—Poe, Tamerlane.

To understand the relationship of Donald MacDeesa to Timour, it is necessary to go back to that day, six years before, when in the turquoise-domed palace at Samarcand the Amir planned the overthrow of the Ottoman.

When other men looked days ahead, Timour looked years; and five years passed before he was ready to move against the Turk, and let Donald ride to Brusa ahead of a carefully trained pursuit. Five years of fierce fighting in the mountain snows and the desert dust, through which Timour moved like a mythical giant, and hard as he drove his chiefs, he drove the Highlander harder. It was as if he studied MacDeesa with the impersonally cruel eyes of a scientist, wringing every ounce of accomplishment from him, seeking to find the limit of man’s endurance and valor—the final breaking-point. He did not find it.

The Gael was too utterly reckless to be trusted with hosts and armies. But in raids and forays, in the storming of cities, and in charges of battle, in any action requiring personal valor and prowess, the Highlander was all but invincible. He was a typical fighting-man of European wars, where tactics and strategy meant little and ferocious hand-to-hand fighting much, and where battles were decided by the physical prowess of the champions. In tricking the Turk, he had but followed the instructions given him by Timour.

There was scant love lost between the Gael and the Amir, to whom Donald was but a ferocious barbarian from the outlands of Frankistan. Timour never showered gifts and honors on Donald, as he did upon his Moslem chiefs. But the grim Gael scorned these gauds, seeming to derive his only pleasures from hard fighting and hard drinking. He ignored the formal reverence paid the Amir by his subjects, and in his cups dared beard the somber Tatar to his face, so that the people caught their breath.

“He is a wolf I unleash on my foes,” said Timour on one occasion to his lords.

“He is a two-edged blade that might cut the wielder,” ventured one of them.

“Not so long as the blade is forever smiting my enemies,” answered Timour.

After Angora, Timour gave Donald command of the Kalmucks, who accompanied their kin back into high Asia, and a swarm of restless, turbulent Vigurs. That was his reward: a wider range and a greater capacity for grinding toil and heart-bursting warfare. But Donald made no comment; he worked his slayers into fighting shape, and experimented with various types of saddles and armor, with firelocks—finding them much inferior in actual execution to the bows of the Tatars—and with the latest type of firearm, the cumbrous wheel-lock pistols used by the Arabs a century before they made their appearance in Europe.

Timour hurled Donald against his foes as a man hurls a javelin, little caring whether the weapon be broken or not. The Gael’s horsemen would come back bloodstained, dusty and weary, their armor hacked to shreds, their swords notched and blunted, but always with the heads of Timour’s foes swinging at their high saddle-peaks. Their savagery, and Donald’s own wild ferocity and superhuman strength, brought them repeatedly out of seemingly hopeless positions. And Donald’s wild-beast vitality caused him again and again to recover from ghastly wounds, until the iron-thewed Tatars marveled at him.

As the years passed, Donald, always aloof and taciturn, withdrew more and more to himself. When not riding on campaigns, he sat alone in brooding silence in the taverns, or stalked dangerously through the streets, hand on his great sword, while the people slunk softly from in front of him. He had one friend, Ak Boga; but one interest outside of war and carnage. On a raid into Persia, a slim white wisp of a girl had run screaming across the path of the charging squadron and his men had seen Donald bend down and sweep her up into his saddle with one mighty hand. The girl was Zuleika, a Persian dancer.

Donald had a house in Samarcand, and a handful of servants, but only this one girl. She was comely, sensual and giddy. She adored her master in her way, and feared him with a very ecstasy of fear, but was not above secret amours with young soldiers when MacDeesa was away on the wars. Like most Persian women of her caste, she had a capacity for petty intrigue and an inability for keeping her small nose out of affairs which were none of her business. She became a tale-bearer for Shadi Mulkh, the Persian paramour of Khalil, Timour’s weak grandson, and thereby indirectly changed the destiny of the world. She was greedy, vain and an outrageous liar, but her hands were soft as drifting snow-flakes when she dressed the wounds of sword and spear on Donald’s iron body. He never beat or cursed her, and though he never caressed or wooed her with gentle words as other men might, it was well known that he treasured her above all worldly possessions and honors.

Timour was growing old; he had played with the world as a man plays with a chessboard, using kings and armies for pawns. As a young chief without wealth or power, he had overthrown his Mongol masters, and mastered them in his turn. Tribe after tribe, race after race, kingdom after kingdom he had broken and molded into his growing empire, which stretched from the Gobi to the Mediterranean, from Moscow to Delhi—the mightiest empire the world ever knew. He had opened the doors of the South and East, and through them flowed the wealth of the earth. He had saved Europe from an Asiatic invasion, when he checked the tide of Turkish conquest—a fact of which he neither knew nor cared. He had built cities and he had destroyed cities. He had made the desert blossom like a garden, and he had turned flowering lands into desert. At his command pyramids of skulls had reared up, and lives flowed out like rivers. His helmeted warlords were exalted above the multitudes and nations cried out in vain beneath his grinding heel, like lost women crying in the mountains at night.

Now he looked eastward, where the purple empire of Cathay dreamed away the centuries. Perhaps, with the waning of life’s tide, it was the old sleeping home-calling of his race; perhaps he remembered the ancient heroic khans, his ancestors, who had ridden southward out of the barren Gobi into the purple kingdoms.

The Grand Vizier shook his head, as he played at chess with his imperial master. He was old and weary, and he dared speak his mind even to Timour.

“My lord, of what avail these endless wars? You have already subjugated more nations than Genghis Khan or Alexander. Rest in the peace of your conquests and complete the work you have begun in Samarcand. Build more stately palaces. Bring here the philosophers, the artists, the poets of the world—”

Timour shrugged his massive shoulders.

“Philosophy and poetry and architecture are good enough in their way, but they are mist and smoke to conquest, for it is on the red splendor of conquest that all these things rest.”

The Vizier played with the ivory pawns, shaking his hoary head.

“My lord, you are like two men—one a builder, the other a destroyer.”

“Perhaps I destroy so that I may build on the ruins of my destruction,” the Amir answered. “I have never sought to reason out this matter. I only know that I am a conqueror before I am a builder, and conquest is my life’s blood.”

“But what reason to overthrow this great weak bulk of Cathay?" protested the Vizier. “It will mean but more slaughter, with which you have already crimsoned the earth—more woe and misery, with helpless people dying like sheep beneath the sword.”

Timour shook his head, half-absently. “What are their lives? They die anyway, and their existence is full of misery. I will draw a band of iron about the heart of Tatary. With this Eastern conquest I will strengthen my throne, and kings of my dynasty shall rule the world for ten thousand years. All the roads of the world shall lead to Samarcand, and there shall be gathered the wonder and mystery and glory of the world—colleges and libraries and stately mosques—marble domes and sapphire towers and turquoise minarets. But first I shall carry out my destiny—and that is Conquest!”

“But winter draws on,” urged the Vizier. “At least wait until spring.”

Timour shook his head, unspeaking. He knew he was old; even his iron frame was showing signs of decay. And sometimes in his sleep he heard the singing of Aljai the Dark-eyed, the bride of his youth, dead for more than forty years. So through the Blue City ran the word, and men left their lovemaking and their wine-bibbing, strung their bows, looked to their harness and took up again the worn old road of conquest.

Timour and his chiefs took with them many of their wives and servants, for the Amir intended to halt at Otrar, his border city, and from thence strike into Cathay when the snows melted in the spring. Such of his lords as remained rode with him—war took a heavy toll of Timour’s hawks.

As usual Donald MacDeesa and his turbulent rogues led the advance. The Gael was glad to take the road after months of idleness, but he brought Zuleika with him. The years were growing more bitter for the giant Highlander, an outlander among alien races. His wild horsemen worshipped him in their savage way, but he was an alien among them, after all, and they could never understand his inmost thoughts. Ak Boga with his twinkling eyes and jovial laughter had been more like the men Donald had known in his youth, but Ak Boga was dead, his great heart stilled forever by the stroke of an Arab scimitar, and in his growing loneliness Donald more and more sought solace in the Persian girl, who could never understand his strange wayward heart, but who somehow partly filled an aching void in his soul. Through the long lonely nights his hands sought her slim form with a dim formless unquiet hunger even she could dimly sense.

In a strange silence Timour rode out of Samarcand at the head of his long glittering columns and the people did not cheer as of old. With bowed heads and hearts crowded with emotions they could not define, they watched the last conqueror ride forth, and then turned again to their petty lives and commonplace, dreary tasks, with a vague instinctive sense that something terrible and splendid and awesome had gone out of their lives forever.

In the teeth of the rising winter the hosts moved, not with the speed of other times when they passed through the land like windblown clouds. They were two hundred thousand strong and they bore with them herds of spare horses, wagons of supplies and great tent-pavilions.

Beyond the pass men call the Gates of Timour, snow fell, and into the teeth of the blizzard the army toiled doggedly. At last it became apparent that even Tatars could not march in such weather, and Prince Khalil went into winter quarters in that strange town called the Stone City, but Timour plunged on with his own troops. Ice lay three feet deep on the Syr when they crossed, and in the hill-country beyond the going became fiercer, and horses and camels stumbled through the drifts, the wagons lurching and rocking. But the will of Timour drove them grimly onward, and at last they came upon the plain and saw the spires of Otrar gleaming through the whirling snow-wrack.

Timour installed himself and his nobles in the palace, and his warriors went thankfully into winter quarters. But he sent for Donald MacDeesa.

“Ordushar lies in our road,” said Timour. “Take two thousand men and storm that city that our road be clear to Cathay with the coming of spring.”

When a man casts a javelin he little cares if it splinter on the mark. Timour would not have sent his valued emirs and chosen warriors on this, the maddest quest he had yet given even Donald. But the Gael cared not; he was more than ready to ride on any adventure which might drown the dim bitter dreams that gnawed deeper and deeper at his heart. At the age of forty MacDeesa’s iron frame was unweakened, his ferocious valor undimmed. But at times he felt old in his heart. His thoughts turned more and more back over the black and crimson pattern of his life with its violence and treachery and savagery; its woe and waste and stark futility. He slept fitfully and seemed to hear half-forgotten voices crying in the night. Sometimes it seemed the keening of Highland pipes skirled through the howling winds.

He roused his wolves, who gaped at the command but obeyed without comment, and rode out of Otrar in a roaring blizzard. It was a venture of the damned.

In the palace of Otrar, Timour drowsed on his divan over his maps and charts, and listened drowsily to the everlasting disputes between the women of his household. The intrigues and jealousies of the Samarcand palaces reached to isolated Otrar. They buzzed about him, wearying him to death with their petty spite. As age stole on the iron Amir, the women looked eagerly to his naming of a successor—his queen Sarai Mulkh Khanum; Khan Zade, wife of his dead son Jahangir. Against the queen’s claim for her son—and Timour’s—Shah Ruhk, was opposed the intrigue of Khan Zade for her son, Prince Khalil, whom the courtesan Shadi Mulkh wrapped about her pink finger.

The Amir had brought Shadi Mulkh with him to Otrar, much against Khalil’s will. The Prince was growing restless in the bleak Stone City and hints reached Timour of discord and threats of insubordination. Sarai Khanum came to the Amir, a gaunt weary woman, grown old in wars and grief.

“The Persian girl sends secret messages to Prince Khalil, stirring him up to deeds of folly,” said the Great Lady. “You are far from Samarcand. Were Khalil to march thither before you—there are always fools ready to revolt, even against the Lord of Lords.”

“At another time,” said Timour wearily, “I would have her strangled. But Khalil in his folly would rise against me, and a revolt at this time, however quickly put down, would upset all my plans. Have her confined and closely guarded, so that she can send no more messages.”

“This I have already done,” replied Sarai Khanum grimly, “but she is clever and manages to get messages out of the palace by means of the Persian girl of the Caphar, lord Donald.”

“Fetch this girl,” ordered Timour, laying aside his maps with a sigh.

They dragged Zuleika before the Amir, who looked somberly upon her as she groveled whimpering at his feet, and with a weary gesture, sealed her doom—and immediately forgot her, as a king forgets the fly he has crushed.

They dragged the girl screaming from the imperial presence and hurled her upon her knees in a hall which had no windows and only bolted doors. Groveling on her knees she wailed frantically for Donald and screamed for mercy, until terror froze her voice in her pulsing throat, and through a mist of horror she saw the stark half-naked figure and the mask-like face of the grim executioner advancing, knife in hand. . . .

Zuleika was neither brave nor admirable. She neither lived with dignity nor met her fate with courage. She was cowardly, immoral and foolish. But even a fly loves life, and a worm would cry out under the heel that crushed it. And perhaps, in the grim inscrutable books of Fate, even an emperor may not forever trample insects with impunity.

“But I have dreamed a dreary dream.

Beyond the Vale of Skye;

I saw a dead man win a fight.

And I think that man was I.”

—Battle of Otterbourne.

And at Ordushar the siege dragged on. In the freezing winds that swept down the pass, driving snow in blinding, biting blasts, the stocky Kalmucks and the lean Vigurs strove and suffered and died in bitter anguish. They set scaling-ladders against the walls and struggled upward, and the defenders, suffering no less, speared them, hurled down boulders that crushed the mailed figures like beetles, and thrust the ladders from the walls so that they crashed down, bearing death to men below. Ordushar was actually but a stronghold of the Jat Mongols, set sheer in the pass and flanked by towering cliffs.

Donald’s wolves hacked at the frozen ground with frost-bitten raw hands which scarce could hold the picks, striving to sink a mine under the walls. They pecked at the towers while molten lead and weighted javelins fell in a rain upon them; driving their spear-points between the stones, tearing out pieces of masonry with their naked hands. With stupendous toil they had constructed makeshift siege-engines from felled trees and the leather of their harness and woven hair from the manes and tails of their warhorses. The rams battered vainly at the massive stones, the ballistas groaned as they launched tree-trunks and boulders against the towers or over the walls. Along the parapets the attackers fought with the defenders, until their bleeding hands froze to spear-shaft and sword-hilt, and the skin came away in great raw strips. And always, with superhuman fury rising above their agony, the defenders hurled back the attack.

A storming-tower was built and rolled up to the walls, and from the battlements the men of Ordushar poured a drenching torrent of naphtha that sent it up in flame and burnt the men in it, shriveling them in their armor like beetles in a fire. Snow and sleet fell in blinding flurries, freezing to sheets of ice. Dead men froze stiffly where they fell, and wounded men died in their sleeping-furs. There was no rest, no surcease from agony. Days and nights merged into a hell of pain. Donald’s men, with tears of suffering frozen on their faces, beat frenziedly against the frosty stone walls, fought with raw hands gripping broken weapons, and died cursing the gods that created them.

The misery inside the city was no less, for there was no more food. At night Donald’s warriors heard the wailing of the starving people in the streets. At last in desperation the men of Ordushar cut the throats of their women and children and sallied forth, and the haggard Tatars fell on them weeping with the madness of rage and woe, and in a welter of battle that crimsoned the frozen snow, drove them back through the city gates. And the struggle went hideously on.

Donald used up the last wood in the vicinity to erect another storming-tower higher than the city wall. After that there was no more wood for the fires. He himself stood at the uplifted bridge which was to be lowered to rest on the parapets. He had not spared himself. Day and night he had toiled beside his men, suffering as they had suffered. The tower was rolled to the wall in a hail of arrows that slew half the warriors who had not found shelter behind the thick bulwark. A crude cannon bellowed from the walls, but the clumsy round shot whistled over their heads. The naphtha and Greek fire of the Jats was exhausted. In the teeth of the singing shafts the bridge was dropped.

Drawing his claymore, Donald strode out upon it. Arrows broke on his corselet and glanced from his helmet. Firelocks flashed and bellowed in his face but he strode on unhurt. Lean armored men with eyes like mad dogs’ swarmed upon the parapet, seeking to dislodge the bridge, to hack it asunder. Among them Donald sprang, his claymore whistling. The great blade sheared through mail-mesh, flesh and bone, and the struggling clump fell apart. Donald staggered on the edge of the wall as a heavy ax crashed on his shield, and he struck back, cleaving the wielder’s spine. The Gael recovered his balance, tossing away his riven shield. His wolves were swarming over the bridge behind him, hurling the defenders from the parapet, cutting them down. Into a swirl of battle Donald strode, swinging his heavy blade. He thought fleetingly of Zuleika, as men in the madness of battle will think of irrelevant things, and it was as if the thought of her had hurt him fiercely under the heart. But it was a spear that had girded through his mail, and Donald struck back savagely; the claymore splintered in his hand and he leaned against the parapet, his face briefly contorted. Around him swept the tides of slaughter as the pent-up fury of his warriors, maddened by the long weeks of suffering, burst all bounds.

“While the red flashing of the light

From clouds that hung, like banners, o’er.

Appeared to my half-closing eye

The pageantry of monarchy.”

—Poe, Tamerlane

To Timour on his throne in the palace of Otrar came the Grand Vizier. “The survivors of the men sent to the Pass of Ordushar are returning, my lord. The city in the mountains is no more. They bear the lord Donald on a litter, and he is dying.”

They brought the litter into Timour’s presence, weary, dull-eyed men, with raw wounds tied up with blood-crusted rags, their garments and mail in tatters. They flung before the Amir’s feet the golden-scaled corselets of chiefs, and chests of jewels and robes of silk and silver braid; the loot of Ordushar where men had starved among riches. And they set the litter down before Timour.

The Amir looked at the form of Donald. The Highlander was pale, but his sinister face showed no hint of weakness in that wild spirit, his cold eyes gleamed unquenched.

“The road to Cathay is clear,” said Donald, speaking with difficulty. “Ordushar lies in smoking ruins. I have carried out your last command.”

Timour nodded, his eyes seeming to gaze through and beyond the Highlander. What was a dying man on a litter to the Amir, who had seen so many die? His mind was on the road to Cathay and the purple kingdoms beyond. The javelin had shattered at last, but its final cast had opened the imperial path. Timour’s dark eyes burned with strange depths and leaping shadows, as the old fire stole through his blood. Conquest! Outside the winds howled, as if trumpeting the roar of nakars, the clash of cymbals, the deep-throated chant of victory.

“Send Zuleika to me,” the dying man muttered. Timour did not reply; he scarcely heard, sitting lost in thunderous visions. He had already forgotten Zuleika and her fate. What was one death in the awesome and terrible scheme of empire.

“Zuleika, where is Zuleika?” the Gael repeated, moving restlessly on his litter. Timour shook himself slightly and lifted his head, remembering.

“I had her put to death,” he answered quietly. “It was necessary.”

“Necessary!” Donald strove to rear upright, his eyes terrible, but fell back, gagging, and spat out a mouthful of crimson. “You bloody dog, she was mine!”

“Yours or another’s,” Timour rejoined absently, his mind far away. “What is a woman in the plan of imperial destinies?”

For answer Donald plucked a pistol from among his robes and fired point-blank. Timour started and swayed on his throne, and the courtiers cried out, paralyzed with horror. Through the drifting smoke they saw that Donald lay dead on the litter, his thin lips frozen in a grim smile. Timour sat crumpled on his throne, one hand gripping his breast; through those fingers blood oozed darkly. With his free hand he waved back his nobles.

“Enough; it is finished. To every man comes the end of the road. Let Pir Muhammad reign in my stead, and let him strengthen the lines of the empire I have reared with my hands.”

A rack of agony twisted his features. “Allah, that this should be the end of empire!” It was a fierce cry of anguish from his inmost soul. “That I, who have trodden upon kingdoms and humbled sultans, come to my doom because of a cringing trull and a Caphar renegade!” His helpless chiefs saw his mighty hands clench like iron as he held death at bay by the sheer power of his unconquered will. The fatalism of his accepted creed had never found resting-place in his instinctively pagan soul; he was a fighter to the red end.

“Let not my people know that Timour died by the hand of a Caphar,” he spoke with growing difficulty. “Let not the chronicles of the ages blazon the name of a wolf that slew an emperor. Ah God, that a bit of dust and metal can dash the Conqueror of the World into the dark! Write, scribe, that this day, by the hand of no man, but by the will of Allah, died Timour, Servant of God.”