Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

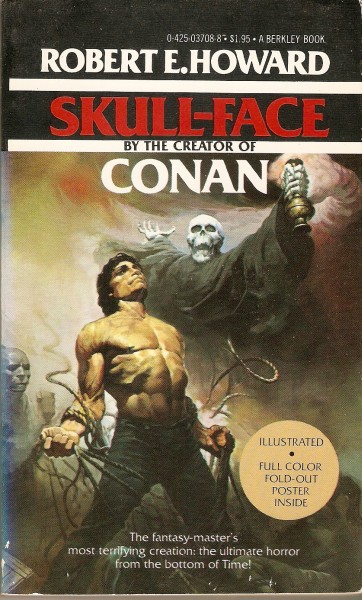

Published in Skull-Face, 1978.

| I | II | III | IV | V |

The onslaught was as unexpected as the stroke of an unseen cobra. One second Steve Harrison was plodding profanely but prosaically through the darkness of the alley—the next, he was fighting for his life with the snarling, mouthing fury that had fallen on him, talon and tooth. The thing was obviously a man, though in the first few dazed seconds Harrison doubted even this fact. The attacker’s style of fighting was appallingly vicious and beast-like, even to Harrison who was accustomed to the foul battling of the underworld.

The detective felt the other’s teeth in his flesh, and yelped profanely. But there was a knife, too; it ribboned his coat and shirt, and drew blood, and only blind chance that locked his fingers about a sinewy wrist, kept the point from his vitals. It was dark as the backdoor of Erebus. Harrison saw his assailant only as a slightly darker chunk in the blackness. The muscles under his grasping fingers were taut and steely as piano wire, and there was a terrifying suppleness about the frame writhing against his which filled Harrison with panic. The big detective had seldom met a man his equal in strength; this denizen of the dark not only was as strong as he, but was lither and quicker and tougher than a civilized man ought to be.

They rolled over into the mud of the alley, biting, kicking and slugging, and though the unseen enemy grunted each time one of Harrison’s maul-like fists thudded against him, he showed no signs of weakening. His wrist was like a woven mass of steel wires, threatening momentarily to writhe out of Harrison’s clutch. His flesh crawling with fear of the cold steel, the detective grasped that wrist with both his own hands, and tried to break it. A bloodthirsty howl acknowledged this futile attempt, and a voice, which had been mouthing in an unknown tongue, hissed in Harrison’s ear: “Dog! You shall die in the mud, as I died in the sand! You gave my body to the vultures! I give yours to the rats of the alley! Wellah!”

A grimy thumb was feeling for Harrison’s eye, and fired to desperation, the detective heaved his body backward, bringing up his knee with bone-crushing force. The unknown gasped and rolled clear, squalling like a cat. Harrison staggered up, lost his balance, caromed against a wall. With a scream and a rush, the other was up and at him. Harrison heard the knife whistle and chunk into the wall beside him, and he lashed out blindly with all the power of his massive shoulders. He landed solidly, felt his victim shoot off his feet backward, and heard him crash headlong into the mud. Then Steve Harrison, for the first time in his life, turned his back on a single foe and ran lumberingly but swiftly up the alley.

His breath came pantingly; his feet splashed through refuse and clanged over rusty cans. Momentarily he expected a knife in his back. “Hogan!” he bawled desperately. Behind him sounded the quick lethal patter of flying feet.

He catapulted out of the black alley mouth head on into Patrolman Hogan who had heard his urgent bellow and was coming on the run. The breath went out of the patrolman in an agonized gasp, and the two hit the sidewalk together.

Harrison did not take time to rise. Ripping the Colt .38 Special from Hogan’s holster, he blazed away at a shadow that hovered for an instant in the black mouth of the alley.

Rising, he approached the dark entrance, the smoking gun in his hand. No sound came from the Stygian gloom.

“Give me your flashlight,” he requested, and Hogan rose, one hand on his capacious belly, and proffered the article. The white beam showed no corpse stretched in the alley mud.

“Got away,” muttered Harrison.

“Who?” demanded Hogan with some spleen. “What is this, anyway? I hear you bellowin’ ‘Hogan!’ like the devil had you by the seat of the britches, and the next thing you ram me like a chargin’ bull. What—”

“Shut up, and let’s explore this alley,” snapped Harrison. “I didn’t mean to run into you. Something jumped me—”

“I’ll say somethin’ did.” The patrolman surveyed his companion in the uncertain light of the distant corner lamp. Harrison’s coat hung in ribbons; his shirt was slashed to pieces, revealing his broad hairy chest which heaved from his exertions. Sweat ran down his corded neck, mingling with blood from gashes on arms, shoulders and breast muscles. His hair was clotted with mud, his clothes smeared with it.

“Must have been a whole gang,” decided Hogan.

“It was one man,” said Harrison; “one man or one gorilla; but it talked. Are you coming?”

“I am not. Whatever it was, it’ll be gone now. Shine that light up the alley. See? Nothin’ in sight. It wouldn’t be waitin’ around for us to grab it by the tail. You better get them cuts dressed. I’ve warned you against short cuts through dark alleys. Plenty men have grudges against you.”

“I’ll go to Richard Brent’s place,” said Harrison. “He’ll fix me up. Go along with me, will you?”

“Sure, but you better let me—”

“What ever it is, no!” growled Harrison, smarting from cuts and wounded vanity. “And listen, Hogan—don’t mention this, see? I want to work it out for myself. This is no ordinary affair.”

“It must not be—when one critter licks the tar out of Iron Man Harrison,” was Hogan’s biting comment; whereupon Harrison cursed under his breath.

Richard Brent’s house stood just off Hogan’s beat—one lone bulwark of respectability in the gradually rising tide of deterioration which was engulfing the neighborhood, but of which Brent, absorbed in his studies, was scarcely aware.

Brent was in his relic-littered study, delving into the obscure volumes which were at once his vocation and his passion. Distinctly the scholar in appearance, he contrasted strongly with his visitors. But he took charge without undue perturbation, summoning to his aid a half course of medical studies.

Hogan, having ascertained that Harrison’s wounds were little more than scratches, took his departure, and presently the big detective sat opposite his host, a long whiskey glass in his massive hand.

Steve Harrison’s height was above medium, but it seemed dwarfed by the breadth of his shoulders and the depth of his chest. His heavy arms hung low, and his head jutted aggressively forward. His low, broad brow, crowned with heavy black hair, suggested the man of action rather than the thinker, but his cold blue eyes reflected unexpected depths of mentality.

“ ‘—As I died in the sand,’ ” he was saying. “That’s what he yammered. Was he just a plain nut—or what the hell?”

Brent shook his head, absently scanning the walls, as if seeking inspiration in the weapons, antique and modern, which adorned it.

“You could not understand the language in which he spoke before?”

“Not a word. All I know is, it wasn’t English and it wasn’t Chinese. I do know the fellow was all steel springs and whale bone. It was like fighting a basketful of wild cats. From now on I pack a gun regular. I haven’t toted one recently, things have been so quiet. Always figured I was a match for several ordinary humans with my fists, anyway. But this devil wasn’t an ordinary human; more like a wild animal.”

He gulped his whiskey loudly, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, and leaned toward Brent with a curious glint in his cold eyes.

“I wouldn’t be saying this to anybody but you,” he said with a strange hesitancy. “And maybe you’ll think I’m crazy—but—well, I’ve bumped off several men in my life. Do you suppose—well, the Chinese believe in vampires and ghouls and walking dead men—and with all this talk about being dead, and me killing him—do you suppose—”

“Nonsense!” exclaimed Brent with an incredulous laugh. “When a man’s dead, he’s dead. He can’t come back.”

“That’s what I’ve always thought,” muttered Harrison. “But what the devil did he mean about me feeding him to the vultures?”

“I will tell you!” A voice hard and merciless as a knife edge cut their conversation.

Harrison and Brent wheeled, the former starting out of his chair. At the other end of the room one of the tall shuttered windows stood open for the sake of the coolness. Before this now stood a tall rangy man whose ill-fitting garments could not conceal the dangerous suppleness of his limbs, nor the breadth of his hard shoulders. Those cheap garments, muddy and bloodstained, seemed incongruous with the fierce dark hawk-like face, the flame of the dark eyes. Harrison grunted explosively, meeting the concentrated ferocity of that glare.

“You escaped me in the darkness,” muttered the stranger, rocking slightly on the balls of his feet as he crouched, catlike, a wicked curved dagger gleaming in his hand. “Fool! Did you dream I would not follow you? Here is light; you shall not escape again!”

“Who the devil are you?” demanded Harrison, standing in an unconscious attitude of defense, legs braced, fists poised.

“Poor of wit and scant of memory!” sneered the other. “You do not remember Amir Amin Izzedin, whom you slew in the Valley of the Vultures, thirty years ago! But I remember! From my cradle I remember. Before I could speak or walk, I knew that I was Amir Amin, and I remembered the Valley of Vultures. But only after deep shame and long wandering was full knowledge revealed to me. In the smoke of Shaitan I saw it! You have changed your garments of flesh, Ahmed Pasha, you Bedouin dog, but you can not escape me. By the Golden Calf!”

With a feline shriek he ran forward, dagger on high. Harrison sprang aside, surprizingly quick for a man of his bulk, and ripped an archaic spear from the wall. With a wordless yell like a warcry, he rushed, gripping it with both hands like a bayonet. Amir Amin wheeled toward him lithely, swaying his pantherish body to avoid the onrushing point. Too late Harrison realized his mistake—knew he would be spitted on the long knife as he plunged past the elusive Oriental. But he could not check his headlong impetus. And then Amir Amin’s foot slipped on a sliding rug. The spear head ripped through his muddy coat, ploughed along his ribs, bringing a spurting stream of blood. Knocked off balance, he slashed wildly, and then Harrison’s bull-like shoulder smashed into him, carrying them both to the floor.

Amir Amin was up first, minus his knife. As he glared wildly about for it, Brent, temporarily stunned by the unaccustomed violence, went into action. From the racks on the wall the scholar had taken a shotgun, and he wore a look of grim determination. As he lifted it, Amir Amin yelped and plunged recklessly through the nearest window. The crash of splintering glass mingled with the thunderous roar of the shotgun. Brent, rushing to the window, blinking in the powder fumes, saw a shadowy form dart across the shadowy lawn, under the trees, and vanish. He turned back into the room, where Harrison was rising, swearing luridly.

“Twice in a night is too danged much! Who is this nut, anyway? I never saw him before!”

“A Druse!” stuttered Brent. “His accent—his mention of the golden calf—his hawk-like appearance—I am sure he is a Druse.”

“What the hell is a Druse?” bellowed Harrison, in a spasm of irritation. His bandages had been torn and his cuts were bleeding again.

“They live in a mountain district in Syria,” answered Brent; “a tribe of fierce fighters—”

“I can tell that,” snarled Harrison. “I never expected to meet anybody that could lick me in a stand-up fight, but this devil’s got me buffaloed. Anyway, it’s a relief to know he’s a living human being. But if I don’t watch my step, I won’t be. I’m staying here tonight, if you’ve got a room where I can lock all the doors and windows. Tomorrow I’m going to see Woon Sun.”

Few men ever traversed the modest curio shop that opened on dingy River Street and passed through the cryptic curtain-hung door at the rear of that shop, to be amazed at what lay beyond: luxury in the shape of gilt-worked velvet hangings, silken cushioned divans, tea-cups of tinted porcelain on toy-like tables of lacquered ebony, over all of which was shed a soft colored glow from electric bulbs concealed in gilded lanterns.

Steve Harrison’s massive shoulders were as incongruous among those exotic surroundings as Woon Sun, short, sleek, clad in close-fitting black silk, was adapted to them.

The Chinaman smiled, but there was iron behind his suave mask.

“And so—” he suggested politely.

“And so I want your help,” said Harrison abruptly. His nature was not that of a rapier, fencing for an opening, but a hammer smashing directly at its objective.

“I know that you know every Oriental in the city. I’ve described this bird to you. Brent says he’s a Druse. You couldn’t be ignorant of him. He’d stand out in any crowd. He doesn’t belong with the general run of River Street gutter rats. He’s a wolf.”

“Indeed he is,” murmured Woon Sun. “It would be useless to try to conceal from you the fact that I know this young barbarian. His name is Ali ibn Suleyman.”

“He called himself something else,” scowled Harrison.

“Perhaps. But he is Ali ibn Suleyman to his friends. He is, as your friend said, a Druse. His tribe live in stone cities in the Syrian mountains—particularly about the mountain called the Djebel Druse.”

“Muhammadans, eh?” rumbled Harrison. “Arabs?”

“No; they are, as it were, a race apart. They worship a calf cast of gold, believe in reincarnation, and practice heathen rituals abhorred by the Moslems. First the Turks and now the French have tried to govern them, but they have never really been conquered.”

“I can believe it, alright,” muttered Harrison. “But why did he call me ‘Ahmed Pasha’? What’s he got it in for me for?”

Woon Sun spread his hands helplessly.

“Well, anyway,” growled Harrison, “I don’t want to keep on dodging knives in back alleys. I want you to fix it so I can get the drop on him. Maybe he’ll talk sense, if I can get the cuffs on him. Maybe I can argue him out of this idea of killing me, whatever it is. He looks more like a fanatic than a criminal. Anyway, I want to find out just what it’s all about.”

“What could I do?” murmured Woon Sun, folding his hands on his round belly, malice gleaming from under his dropping lids. “I might go further and ask, why should I do anything for you?”

“You’ve stayed inside the law since coming here,” said Harrison. “I know that curio shop is just a blind; you’re not making any fortune out of it. But I know, too, that you’re not mixed up with anything crooked. You had your dough when you came here—plenty of it—and how you got it is no concern of mine.

“But, Woon Sun,” Harrison leaned forward and lowered his voice, “do you remember that young Eurasian Josef La Tour? I was the first man to reach his body, the night he was killed in Osman Pasha’s gambling den. I found a note book on him, and I kept it. Woon Sun, your name was in that book!”

An electric silence impregnated the atmosphere. Woon Sun’s smooth yellow features were immobile, but red points glimmered in the shoe-button blackness of his eyes.

“La Tour must have been intending to blackmail you,” said Harrison. “He’d worked up a lot of interesting data. Reading that note book, I found that your name wasn’t always Woon Sun; found out where you got your money, too.”

The red points had faded in Woon Sun’s eyes; those eyes seemed glazed; a greenish pallor overspread the yellow face.

“You’ve hidden yourself well, Woon Sun,” muttered the detective. “But double-crossing your society and skipping with all their money was a dirty trick. If they ever find you, they’ll feed you to the rats. I don’t know but what it’s my duty to write a letter to a mandarin in Canton, named—”

“Stop!” The Chinaman’s voice was unrecognizable. “Say no more, for the love of Buddha! I will do as you ask. I have this Druse’s confidence, and can arrange it easily. It is now scarcely dark. At midnight be in the alley known to the Chinese of River Street as the Alley of Silence. You know the one I mean? Good. Wait in the nook made by the angle of the walls, near the end of the alley, and soon Ali ibn Suleyman will walk past it, ignorant of your presence. Then if you dare, you can arrest him.”

“I’ve got a gun this time,” grunted Harrison. “Do this for me, and we’ll forget about La Tour’s note book. But no double-crossing, or—”

“You hold my life in your fingers,” answered Woon Sun. “How can I double-cross you?”

Harrison grunted skeptically, but rose without further words, strode through the curtained door and through the shop, and let himself into the street. Woon Sun watched inscrutably the broad shoulders swinging aggressively through the swarms of stooped, hurrying Orientals, men and women, who thronged River Street at that hour; then he locked the shop door and hurried back through the curtained entrance into the ornate chamber behind. And there he halted, staring.

Smoke curled up in a blue spiral from a satin divan, and on that divan lounged a young woman—a slim, dark, supple creature, whose night-black hair, full red lips and scintillant eyes hinted at blood more exotic than her costly garments suggested. Those red lips curled in malicious mockery, but the glitter of her dark eyes belied any suggestion of humor, however satirical, just as their vitality belied the languor expressed in the listlessly drooping hand that held the cigaret.

“Joan!” The Chinaman’s eyes narrowed to slits of suspicion. “How did you get in here?”

“Through that door over there, which opens on a passage which in turn opens on the alley that runs behind this building. Both doors were locked—but long ago I learned how to pick locks.”

“But why—?”

“I saw the brave detective come here. I have been watching him for some time now—though he does not know it.” The girl’s vital eyes smoldered yet more deeply for an instant.

“Have you been listening outside the door?” demanded Woon Sun, turning grey.

“I am no eavesdropper. I did not have to listen. I can guess why he came. And you promised to help him?”

“I don’t know what you are talking about,” answered Woon Sun, with a secret sigh of relief.

“You lie!” The girl came tensely upright on the divan, her convulsive fingers crushing her cigaret, her beautiful face momentarily contorted. Then she regained control of herself, in a cold resolution more dangerous than spitting fury. “Woon Sun,” she said calmly, drawing a stubby black automatic from her mantle, “how easily, and with what good will could I kill you where you stand. But I do not wish to. We shall remain friends. See, I replace the gun. But do not tempt me, my friend. Do not try to eject me, or to use violence with me. Here, sit down and take a cigaret. We will talk this over calmly.”

“I do not know what you wish to talk over,” said Woon Sun, sinking down on a divan and mechanically taking the cigaret she offered, as if hypnotized by the glitter of her magnetic black eyes—and the knowledge of the hidden pistol. All his Oriental immobility could not conceal the fact that he feared this young pantheress—more than he feared Harrison. “The detective came here merely on a friendly call,” he said. “I have many friends among the police. If I were found murdered they would go to much trouble to find and hang the guilty person.”

“Who spoke of killing?” protested Joan, snapping a match on a pointed, henna-tinted nail, and holding the tiny flame to Woon Sun’s cigaret. At the instant of contact their faces were close together, and the Chinaman drew back from the strange intensity that burned in her dark eyes. Nervously he drew on the cigaret, inhaling deeply.

“I have been your friend,” he said. “You should not come here threatening me with a pistol. I am a man of no small importance on River Street. You, perhaps, are not as secure as you suppose. The time may come when you will need a friend like me—”

He was suddenly aware that the girl was not answering him, or even heeding his words. Her own cigaret smoldered unheeded in her fingers, and through the clouds of smoke her eyes burned at him with the terrible eagerness of a beast of prey. With a gasp he jerked the cigaret from his lips and held it to his nostrils.

“She-devil!” It was a shriek of pure terror. Hurling the smoking stub from him, he lurched to his feet where he swayed dizzily on legs suddenly grown numb and dead. His fingers groped toward the girl with strangling motions. “Poison—dope—the black lotos—”

She rose, thrust an open hand against the flowered breast of his silk jacket and shoved him back down on the divan. He fell sprawling and lay in a limp attitude, his eyes open, but glazed and vacant. She bent over him, tense and shuddering with the intensity of her purpose.

“You are my slave,” she hissed, as a hypnotizer impels his suggestions upon his subject. “You have no will but my will. Your conscious brain is asleep, but your tongue is free to tell the truth. Only the truth remains in your drugged brain. Why did the detective Harrison come here?”

“To learn of Ali ibn Suleyman, the Druse,” muttered Woon Sun in his own tongue, and in a curious lifeless sing-song.

“You promised to betray the Druse to him?”

“I promised but I lied,” the monotonous voice continued. “The detective goes at midnight to the Alley of Silence, which is the Gateway to the Master. Many bodies have gone feet-first through that gateway. It is the best place to dispose of his corpse. I will tell the Master he came to spy upon him, and thus gain honor for myself, as well as ridding myself of an enemy. The white barbarian will stand in the nook between the walls, awaiting the Druse as I bade him. He does not know that a trap can be opened in the angle of the walls behind him and a hand strike with a hatchet. My secret will die with him.”

Apparently Joan was indifferent as to what the secret might be, since she questioned the drugged man no further. But the expression on her beautiful face was not pleasant.

“No, my yellow friend,” she murmured. “Let the white barbarian go to the Alley of Silence—aye, but it is not a yellow-belly who will come to him in the darkness. He shall have his desire. He shall meet Ali ibn Suleyman; and after him, the worms that writhe in darkness!”

Taking a tiny jade vial from her bosom, she poured wine from a porcelain jug into an amber goblet, and shook into the liquor the contents of the vial. Then she put the goblet into Woon Sun’s limp fingers and sharply ordered him to drink, guiding the beaker to his lips. He gulped the wine mechanically, and immediately slumped sidewise on the divan and lay still.

“You will wield no hatchet this night,” she muttered. “When you awaken many hours from now, my desire will have been accomplished—and you will need fear Harrison no longer, either—whatever may be his hold upon you.” She seemed struck by a sudden thought and halted as she was turning toward the door that opened on the corridor.

“ ‘Not as secure as I suppose’—” she muttered, half aloud. “What could he have meant by that?” A shadow, almost of apprehension, crossed her face. Then she shrugged her shoulders. “Too late to make him tell me now. No matter. The Master does not suspect—and what if he did? He’s no Master of mine. I waste too much time—”

She stepped into the corridor, closing the door behind her. Then when she turned, she stopped short. Before her stood three grim figures, tall, gaunt, black-robed, their shaven vulture-like heads nodding in the dim light of the corridor.

In that instant, frozen with awful certainty, she forgot the gun in her bosom. Her mouth opened for a scream, which died in a gurgle as a bony hand was clapped over her lips.

The alley, nameless to white men, but known to the teeming swarms of River Street as the Alley of Silence, was as devious and cryptic as the characteristics of the race which frequented it. It did not run straight, but, slanting unobtrusively off River Street, wound through a maze of tall, gloomy structures, which, to outward seeming at least, were tenements and warehouses, and crumbling forgotten buildings apparently occupied only by rats, where boarded-up windows stared blankly.

As River Street was the heart of the Oriental quarter, so the Alley of Silence was the heart of River Street, though apparently empty and deserted. At least that was Steve Harrison’s idea, though he could give no definite reason why he ascribed so much importance to a dark, dirty, crooked alley that seemed to go nowhere. The men at headquarters twitted him, telling him that he had worked so much down in the twisty mazes of rat-haunted River Street that he was getting a Chinese twist in his mind.

He thought of this, as he crouched impatiently in the angle formed by the last crook of that unsavory alley. That it was past midnight he knew from a stealthy glance at the luminous figures on his watch. Only the scurrying of rats broke the silence. He was well hidden in a cleft formed by two jutting walls, whose slanting planes came together to form a triangle opening on the alley. Alley architecture was as crazy as some of the tales which crept forth from its dank blackness. A few paces further on the alley ended abruptly at the cliff-like blankness of a wall, in which showed no windows and only a boarded-up door.

This Harrison knew only by a vague luminance which filtered greyly into the alley from above. Shadows lurked along the angles darker than the Stygian pits, and the boarded-up door was only a vague splotch in the sheer of the wall. An empty warehouse, Harrison supposed, abandoned and rotting through the years. Probably it fronted on the bank of the river, ledged by crumbling wharfs, forgotten and unused in the years since the river trade and activity had shifted into a newer part of the city.

He wondered if he had been seen ducking into the alley. He had not turned directly off River Street, with its slinking furtive shapes that drifted silently past all night long. He had come in from a wandering side street, working his way between leaning walls and jutting corners until he came out into the dark winding alley. He had not worked the Oriental quarter for so long, not to have absorbed some of the stealth and wariness of its inhabitants.

But midnight was past, and no sign of the man he hunted. Then he stiffened. Some one was coming up the alley. But the gait was a shuffling step; not the sort he would have connected with a man like Ali ibn Suleyman. A tall stooped figure loomed vaguely in the gloom and shuffled on past the detective’s covert. His trained eye, even in the dimness, told Harrison that the man was not the one he sought.

The unknown went straight to the blank door and knocked three times with a long interval between the raps. Abruptly a red disk glowed in the door. Words were hissed in Chinese. The man on the outside replied in the same tongue, and his words came clearly to the tensed detective: “Erlik Khan!” Then the door unexpectedly opened inward, and he passed through, illumined briefly in the reddish light which streamed through the opening. Then darkness followed the closing of the door, and silence reigned again in the alley of its name.

But crouching in the shadowed angle, Harrison felt his heart pound against his ribs. He had recognized the fellow who passed through the door as a Chinese killer with a price on his head; but it was not that recognition which sent the detective’s blood pumping through his veins. It was the password muttered by the evil-visaged visitant: “Erlik Khan!” It was like the materialization of a dim nightmare dream; like the confirmation of an evil legend.

For more than a year rumors had crept snakily out of the black alleys and crumbling doorways behind which the mysterious yellow people moved phantom-like and inscrutable. Scarcely rumors, either; that was a term too concrete and definite to be applied to the maunderings of dope-fiends, the ravings of madmen, the whimpers of dying men—disconnected whispers that died on the midnight wind. Yet through these disjointed mutterings had wound a dread name, fearsomely repeated, in shuddering whispers: “Erlik Khan!”

It was a phrase always coupled with dark deeds; it was like a black wind moaning through midnight trees; a hint, a breath, a myth, that no man could deny or affirm. None knew if it were the name of a man, a cult, a course of action, a curse, or a dream. Through its associations it became a slogan of dread: a whisper of black water lapping at rotten piles; of blood dripping on slimy stones; of death whimpers in dark corners; of stealthy feet shuffling through the haunted midnight to unknown dooms.

The men at headquarters had laughed at Harrison when he swore that he sensed a connection between various scattered crimes. They had told him, as usual, that he had worked too long among the labyrinths of the Oriental district. But that very fact made him more sensitive to furtive and subtle impressions than were his mates. And at times he had seemed almost to sense a vague and monstrous Shape that moved behind a web of illusion.

And now, like the hiss of an unseen serpent in the dark, had come to him at least as much concrete assurance as was contained in the whispered words: “Erlik Khan!”

Harrison stepped from his nook and went swiftly toward the boarded door. His feud with Ali ibn Suleyman was pushed into the background. The big dick was an opportunist; when chance presented itself, he seized it first and made plans later. And his instinct told him that he was on the threshold of something big.

A slow, almost imperceptible drizzle had begun. Overhead, between the towering black walls, he got a glimpse of thick grey clouds, hanging so low they seemed to merge with the lofty roofs, dully reflecting the glow of the city’s myriad lights. The rumble of distant traffic came to his ears faintly and faraway. His environs seemed curiously strange, alien and aloof. He might have been stealing through the gloom of Canton, or forbidden Peking—or of Babylon, or Egyptian Memphis.

Halting before the door, he ran his hands lightly over it, and over the boards which apparently sealed it. And he discovered that some of the bolt-heads were false. It was an ingenious trick to make the door appear inaccessible to the casual glance.

Setting his teeth, with a feeling as of taking a blind plunge in the dark, Harrison rapped three times as he had heard the killer, Fang Yim, rap. Almost instantly a round hole opened in the door, level with his face, and framed dimly in a red glow he glimpsed a yellow Mongoloid visage. Sibilant Chinese hissed at him.

Harrison’s hat was pulled low over his eyes, and his coat collar, turned up against the drizzle, concealed the lower part of his features. But the disguise was not needed. The man inside the door was no one Harrison had ever seen.

“Erlik Khan!” muttered the detective. No suspicion shadowed the slant eyes. Evidently white men had passed through that door before. It swung inward, and Harrison slouched through, shoulders hunched, hands thrust deep in his coat pockets, the very picture of a waterfront hoodlum. He heard the door closed behind him, and found himself in a small square chamber at the end of a narrow corridor. He noted that the door was furnished with a great steel bar, which the Chinaman was now lowering into place in the heavy iron sockets set on each side of the portal, and the hole in the center was covered by a steel disk, working on a hinge. Outside of a squatting-cushion beside the door for the doorman, the chamber was without furnishings.

All this Harrison’s trained eye took in at a glance, as he slouched across the chamber. He felt that he would not be expected, as a denizen of whatever resort the place proved to be, to remain long in the room. A small red lantern, swinging from the ceiling, lighted the chamber, but the corridor seemed to be without lumination, save such as was furnished by the aforesaid lantern.

Harrison slouched on down the shadowy corridor, giving no evidence of the tensity of his nerves. He noted, with sidelong glances, the firmness and newness of the walls. Obviously a great deal of work had recently been done on the interior of this supposedly deserted building.

Like the alley outside, the corridor did not run straight. Ahead of him it bent at an angle, around which shone a mellow stream of light, and beyond this bend Harrison heard a light padding step approaching. He grabbed at the nearest door, which opened silently under his hand, and closed as silently behind him. In pitch darkness he stumbled over steps, nearly falling, catching at the wall, and cursing the noise he made. He heard the padding step halt outside the door; then a hand pushed against it. But Harrison had his forearm and elbow braced against the panel. His groping fingers found a bolt and he slid it home, wincing at the faint scraping it made. A voice hissed something in Chinese, but Harrison made no answer. Turning, he groped his way hurriedly down the stairs.

Presently his feet struck a level floor, and in another instant he bumped into a door. He had a flashlight in his pocket, but he dared not use it. He fumbled at the door and found it unlocked. The edges, sill and jambs seemed to be padded. The walls, too, seemed to be specially treated, beneath his sensitive fingers. He wondered with a shiver what cries and noises those walls and padded doors were devised to drown.

Shoving open the door, he blinked in a flood of soft reddish light, and drew his gun in a panic. But no shouts or shots greeted him, and as his eyes became accustomed to the light, he saw that he was looking into a great basement-like room, empty except for three huge packing cases. There were doors at either end of the room, and along the sides, but they were all closed. Evidently he was some distance under the ground.

He approached the packing cases, which had apparently but recently been opened, their contents not yet removed. The boards of the lids lay on the floor beside them, with wads of excelsior and tow packing.

“Booze?” he muttered to himself. “Dope? Smugglers?”

He scowled down into the nearest case. A single layer of tow sacking covered the contents, and he frowned in puzzlement at the outlines under that sacking. Then suddenly, with his skin crawling, he snatched at the sacking and pulled it away—and recoiled, choking in horror. Three yellow faces, frozen and immobile, stared sightlessly up at the swinging lamp. There seemed to be another layer underneath—

Gagging and sweating, Harrison went about his grisly task of verifying what he could scarcely believe. And then he mopped away the beads of perspiration.

“Three packing cases full of dead Chinamen!” he whispered shakily. “Eighteen yellow stiffs! Great cats! Talk about wholesale murder! I thought I’d bumped into so many hellish sights that nothing could upset me. But this is piling it on too thick!”

It was the stealthy opening of a door which roused him from his morbid meditations. He wheeled, galvanized. Before him crouched a monstrous and brutish shape, like a creature out of a nightmare. The detective had a glimpse of a massive, half-naked torso, a bullet-like shaven head split by a toothy and slavering grin—then the brute was upon him.

Harrison was no gunman; all his instincts were of the strong-arm variety. Instead of drawing his gun, he dashed his right mauler into that toothy grin, and was rewarded by a jet of blood. The creature’s head snapped back at an agonized angle, but his bony fingers had locked on the detective’s lapels. Harrison drove his left wrist-deep into his assailant’s midriff, causing a green tint to overspread the coppery face, but the fellow hung on, and with a wrench, pulled Harrison’s coat down over his shoulders. Recognizing a trick meant to imprison his arms, Harrison did not resist the movement, but rather aided it, with a headlong heave of his powerful body that drove his lowered head hard against the yellow man’s breastbone, and tore his own arms free of the clinging sleeves.

The giant staggered backward, gasping for breath, holding the futile garment like a shield before him, and Harrison, inexorable in his attack, swept him back against the wall by the sheer force of his rush, and smashed a bone-crushing left and right to his jaw. The yellow giant pitched backward, his eyes already glazed; his head struck the wall, fetching blood in streams, and he toppled face-first to the floor where he lay twitching, his shaven head in a spreading pool of blood.

“A Mongol strangler!” panted Harrison, glaring down at him. “What kind of a nightmare is this, anyway?”

It was just at that instant that a blackjack, wielded from behind, smashed down on his head; the lights went out.

Some misplaced connection with his present condition caused Steve Harrison to dream fitfully of the Spanish Inquisition just before he regained consciousness. Possibly it was the clank of steel chains. Drifting back from a land of enforced dreams, his first sensation was that of an aching head, and he touched it tenderly and swore bitterly.

He was lying on a concrete floor. A steel band girdled his waist, hinged behind, and fastened before with a heavy steel lock. To that band was riveted a chain, the other end of which was made fast to a ring in the wall. A dim lantern suspended from the ceiling lighted the room, which seemed to have but one door and no window. The door was closed.

Harrison noted other objects in the room, and as he blinked and they took definite shape, he was aware of an icy premonition, too fantastic and monstrous for credit. Yet the objects at which he was staring were incredible, too.

There was an affair with levers and windlasses and chains. There was a chain suspended from the ceiling, and some objects that looked like iron fire tongs. And in one corner there was a massive, grooved block, and beside it leaned a heavy broad-edged axe. The detective shuddered in spite of himself, wondering if he were in the grip of some damnable medieval dream. He could not doubt the significance of those objects. He had seen their duplicates in museums—

Aware that the door had opened, he twisted about and glared at the figure dimly framed there—a tall, shadowy form, clad in night-black robes. This figure moved like a shadow of Doom into the chamber, and closed the door. From the shadow of a hood, two icy eyes glittered eerily, framed in a dim yellow oval of a face.

For an instant the silence held, broken suddenly by the detective’s irate bellow.

“What the hell is this? Who are you? Get this chain off me!”

A scornful silence was the only answer, and under the unwinking scrutiny of those ghostly eyes, Harrison felt cold perspiration gather on his forehead and among the hairs on the backs of his hands.

“You fool!” At the peculiar hollow quality of the voice, Harrison started nervously. “You have found your doom!”

“Who are you?” demanded the detective.

“Men call me Erlik Khan, which signifies Lord of the Dead,” answered the other. A trickle of ice meandered down Harrison’s spine, not so much from fear, but because of the grisly thrill in the realization that at last he was face to face with the materialization of his suspicions.

“So Erlik Khan is a man, after all,” grunted the detective. “I’d begun to believe that it was the name of a Chinese society.”

“I am no Chinese,” returned Erlik Khan. “I am a Mongol—direct descendant of Genghis Khan, the great conqueror, before whom all Asia bowed.”

“Why tell me this?” growled Harrison, concealing his eagerness to hear more.

“Because you are soon to die,” was the tranquil reply, “and I would have you realize that it is into the hands of no common gangster scum you have blundered.

“I was head of a lamasery in the mountains of Inner Mongolia, and, had I been able to attain my ambitions, would have rebuilt a lost empire—aye, the old empire of Genghis Khan. But I was opposed by various fools, and barely escaped with my life.

“I came to America, and here a new purpose was born in me: that of forging all secret Oriental societies into one mighty organization to do my bidding and reach unseen tentacles across the seas into hidden lands. Here, unsuspected by such blundering fools as you, have I built my castle. Already I have accomplished much. Those who oppose me die suddenly, or—you saw those fools in the packing cases in the cellar. They are members of the Yat Soy, who thought to defy me.”

“Judas!” muttered Harrison. “A whole tong scuppered!”

“Not dead,” corrected Erlik Khan. “Merely in a cataleptic state, induced by certain drugs introduced into their liquor by trusted servants. They were brought here in order that I might convince them of their folly in opposing me. I have a number of underground crypts like this one, wherein are implements and machines calculated to change the mind of the most stubborn.”

“Torture chambers under River Street!” muttered the detective. “Damned if this isn’t a nightmare!”

“You, who have puzzled so long amidst the mazes of River Street, are you surprized at the mysteries within its mysteries?” murmured Erlik Khan. “Truly, you have but touched the fringes of its secrets. Many men do my bidding—Chinese, Syrians, Mongols, Hindus, Arabs, Turks, Egyptians.”

“Why?” demanded Harrison. “Why should so many men of such different and hostile religions serve you—”

“Behind all differences of religion and belief,” said Erlik Khan, “lies the eternal Oneness that is the essence and root-stem of the East. Before Muhammad was, or Confucius, or Gautama, there were signs and symbols, ancient beyond belief, but common to all sons of the Orient. There are cults stronger and older than Islam or Buddhism—cults whose roots are lost in the blackness of the dawn ages, before Babylon was, or Atlantis sank.

“To an adept, these young religions and beliefs are but new cloaks, masking the reality beneath. Even to a dead man I can say no more. Suffice to know that I, whom men call Erlik Khan, have power above and behind the powers of Islam or of Buddha.”

Harrison lay silent, meditating over the Mongol’s words, and presently the latter resumed: “You have but yourself to blame for your plight. I am convinced that you did not come here tonight to spy upon me—poor, blundering, barbarian fool, who did not even guess my existence. I have learned that you came in your crude way, expecting to trap a servant of mine, the Druse Ali ibn Suleyman.”

“You sent him to kill me,” growled Harrison.

A scornful laugh put his teeth on edge.

“Do you fancy yourself so important? I would not turn aside to crush a blind worm. Another put the Druse on your trail—a deluded person, a miserable, egoistic fool, who even now is paying the price of folly.

“Ali ibn Suleyman is, like many of my henchmen, an outcast from his people, his life forfeit.

“Of all virtues, the Druses most greatly esteem the elementary one of physical courage. When a Druse shows cowardice, none taunts him, but when the warriors gather to drink coffee, some one spills a cup on his abba. That is his death-sentence. At the first opportunity, he is obliged to go forth and die as heroically as possible.

“Ali ibn Suleyman failed on a mission where success was impossible. Being young, he did not realize that his fanatical tribe would brand him as a coward because, in failing, he had not got himself killed. But the cup of shame was spilled on his robe. Ali was young; he did not wish to die. He broke a custom of a thousand years; he fled the Djebel Druse and became a wanderer over the earth.

“Within the past year he joined my followers, and I welcomed his desperate courage and terrible fighting ability. But recently the foolish person I mentioned decided to use him to further a private feud, in no way connected with my affairs. That was unwise. My followers live but to serve me, whether they realize it or not.

“Ali goes often to a certain house to smoke opium, and this person caused him to be drugged with the dust of the black lotos, which produces a hypnotic condition, during which the subject is amenable to suggestions, which, if continually repeated, carry over into the victim’s waking hours.

“The Druses believe that when a Druse dies, his soul is instantly reincarnated in a Druse baby. The great Druse hero, Amir Amin Izzedin, was killed by the Arab shaykh Ahmed Pasha, the night Ali ibn Suleyman was born. Ali has always believed himself to be the reincarnated soul of Amir Amin, and mourned because he could not revenge his former self on Ahmed Pasha, who was killed a few days after he slew the Druse chief.

“All this the person ascertained, and by means of the black lotos, known as the Smoke of Shaitan, convinced the Druse that you, detective Harrison, were the reincarnation of his old enemy Shaykh Ahmed Pasha. It took time and cunning to convince him, even in his drugged condition, that an Arab shaykh could be reincarnated in an American detective, but the person was very clever, and so at last Ali was convinced, and disobeyed my orders—which were never to molest the police, unless they got in my way, and then only according to my directions. For I do not woo publicity. He must be taught a lesson.

“Now I must go. I have spent too much time with you already. Soon one will come who will lighten you of your earthly burdens. Be consoled by the realization that the foolish person who brought you to this pass is expiating her crime likewise. In fact, separated from you but by that padded partition. Listen!”

From somewhere near rose a feminine voice, incoherent but urgent.

“The foolish one realizes her mistake,” smiled Erlik Khan benevolently. “Even through these walls pierce her lamentations. Well, she is not the first to regret foolish actions in these crypts. And now I must begone. Those foolish Yat Soys will soon begin to awaken.”

“Wait, you devil!” roared Harrison, struggling up against his chain. “What—”

“Enough, enough!” There was a touch of impatience in the Mongol’s tone. “You weary me. Get you to your meditations, for your time is short. Farewell, Mr. Harrison—not au revoir.”

The door closed silently, and the detective was left alone with his thoughts which were far from pleasant. He cursed himself for falling into that trap; cursed his peculiar obsession for always working alone. None knew of the tryst he had tried to keep; he had divulged his plans to no one.

Beyond the partition the muffled sobs continued. Sweat began to bead Harrison’s brow. His nerves, untouched by his own plight, began to throb in sympathy with that terrified voice.

Then the door opened again, and Harrison, twisting about, knew with numbing finality that he looked on his executioner. It was a tall, gaunt Mongol, clad only in sandals and a trunk-like garment of yellow silk, from the girdle of which depended a bunch of keys. He carried a great bronze bowl and some objects that looked like joss sticks. These he placed on the floor near Harrison, and squatting just out of the captive’s reach, began to arrange the evil-smelling sticks in a sort of pyramidal shape in the bowl. And Harrison, glaring, remembered a half-forgotten horror among the myriad dim horrors of River Street: a corpse he had found in a sealed room where acrid fumes still hovered over a charred bronze bowl—the corpse of a Hindu, shriveled and crinkled like old leather—mummified by a lethal smoke that killed and shrunk the victim like a poisoned rat.

From the other cell came a shriek so sharp and poignant that Harrison jumped and cursed. The Mongol halted in his task, a match in his hand. His parchment-like visage split in a leer of appreciation, disclosing the withered stump of a tongue; the man was a mute.

The cries increased in intensity, seemingly more in fright than in pain, yet an element of pain was evident. The mute, rapt in his evil glee, rose and leaned nearer the wall, cocking his ear as if unwilling to miss any whimper of agony from that torture cell. Slaver dribbled from the corner of his loose mouth; he sucked his breath in eagerly, unconsciously edging nearer the wall—Harrison’s foot shot out, hooked suddenly and fiercely about the lean ankle. The Mongol threw wild arms aloft, and toppled into the detective’s waiting arms.

It was with no scientific wrestling hold that Harrison broke the executioner’s neck. His pent-up fury had swept away everything but a berserk madness to grip and rend and tear in primitive passion. Like a grizzly he grappled and twisted, and felt the vertebrae give way like rotten twigs.

Dizzy with glutted fury he struggled up, still gripping the limp shape, gasping incoherent blasphemy. His fingers closed on the keys dangling at the dead man’s belt, and ripping them free, he hurled the corpse savagely to the floor in a paroxysm of excess ferocity. The thing struck loosely and lay without twitching, the sightless face grinning hideously back over the yellow shoulder.

Harrison mechanically tried the keys in the lock at his waist. An instant later, freed of his shackles, he staggered in the middle of the cell, almost overcome by the wild rush of emotion—hope, exultation, and the realization of freedom. He snatched up the grim axe that leaned against the darkly stained block, and could have yelled with bloodthirsty joy as he felt the perfect balance of the weighty weapon, and saw the dim light gleaming on its flaring razor-edge.

An instant’s fumbling with the keys at the lock, and the door opened. He looked out into a narrow corridor, dimly lighted, lined with closed doors. From one next to his, the distressing cries were coming, muffled by the padded door and the specially treated walls.

In his berserk wrath he wasted no time in trying his keys on that door. Heaving up the sturdy axe with both hands, he swung it crashing against the panels, heedless of the noise, mindful only of his frenzied urge to violent action. Under his flailing strokes the door burst inward and through its splintered ruins he lunged, eyes glaring, lips asnarl.

He had come into a cell much like the one he had just quitted. There was a rack—a veritable medieval devil-machine—and in its cruel grip writhed a pitiful white figure—a girl, clad only in a scanty chemise. A gaunt Mongol bent over the handles, turning them slowly. Another was engaged in heating a pointed iron over a small brazier.

This he saw at a glance, as the girl rolled her head toward him and cried out in agony. Then the Mongol with the iron ran at him silently, the glowing, white-hot steel thrust forward like a spear. In the grip of red fury though he was, Harrison did not lose his head. A wolfish grin twisting his thin lips, he side stepped, and split the torturer’s head as a melon is split. Then as the corpse tumbled down, spilling blood and brains, he wheeled catlike to meet the onslaught of the other.

The attack of this one was silent as that of the other. They too were mutes. He did not lunge in so recklessly as his mate, but his caution availed him little as Harrison swung his dripping axe. The Mongol threw up his left arm, and the curved edge sheared through muscle and bone, leaving the limb hanging by a shred of flesh. Like a dying panther the torturer sprang in turn, driving in his knife with the fury of desperation. At the same instant the bloody axe flailed down. The thrusting knife point tore through Harrison’s shirt, ploughed through the flesh over his breastbone, and as he flinched involuntarily, the axe turned in his hand and struck flat, crushing the Mongol’s skull like an egg shell.

Swearing like a pirate, the detective wheeled this way and that, glaring for new foes. Then he remembered the girl on the rack.

And then he recognized her at last. “Joan La Tour! What in the name—”

“Let me go!” she wailed. “Oh, for God’s sake, let me go!”

The mechanism of the devilish machine balked him. But he saw that she was tied by heavy cords on wrists and ankles, and cutting them, he lifted her free. He set his teeth at the thought of the ruptures, dislocated joints and torn sinews that she might have suffered, but evidently the torture had not progressed far enough for permanent injury. Joan seemed none the worse, physically, for her experience, but she was almost hysterical. As he looked at the cowering, sobbing figure, shivering in her scanty garment, and remembered the perfectly poised, sophisticated, and self-sufficient beauty as he had known her, he shook his head in amazement. Certainly Erlik Khan knew how to bend his victims to his despotic will.

“Let us go,” she pleaded between sobs. “They’ll be back—they will have heard the noise—”

“Alright,” he grunted; “but where the devil are we?”

“I don’t know,” she whimpered. “Somewhere in the house of Erlik Khan. His Mongol mutes brought me here earlier tonight, through passages and tunnels connecting various parts of the city with this place.”

“Well, come on,” said he. “We might as well go somewhere.”

Taking her hand he led her out into the corridor, and glaring about uncertainly, he spied a narrow stair winding upward. Up this they went, to be halted soon by a padded door, which was not locked. This he closed behind him, and tried to lock, but without success. None of his keys would fit the lock.

“I don’t know whether our racket was heard or not,” he grunted, “unless somebody was nearby. This building is fixed to drown noise. We’re in some part of the basement, I reckon.”

“We’ll never get out alive,” whimpered the girl. “You’re wounded—I saw blood on your shirt—”

“Nothing but a scratch,” grunted the big detective, stealthily investigating with his fingers the ugly ragged gash that was soaking his torn shirt and waist-band with steadily seeping blood. Now that his fury was beginning to cool, he felt the pain of it.

Abandoning the door, he groped upward in thick darkness, guiding the girl of whose presence he was aware only by the contact of a soft little hand trembling in his. Then he heard her sobbing convulsively.

“This is all my fault! I got you into this! The Druse, Ali ibn Suleyman—”

“I know,” he grunted; “Erlik Khan told me. But I never suspected that you were the one who put this crazy heathen up to knifing me. Was Erlik Khan lying?”

“No,” she whimpered. “My brother—Josef. Until tonight I thought you killed him.”

He started convulsively.

“Me? I didn’t do it! I don’t know who did. Somebody shot him over my shoulder—aiming at me, I reckon, during that raid on Osman Pasha’s joint.”

“I know, now,” she muttered. “But I’d always believed you lied about it. I thought you killed him, yourself. Lots of people think that, you know. I wanted revenge. I hit on what looked like a sure scheme. The Druse doesn’t know me. He’s never seen me, awake. I bribed the owner of the opium-joint that Ali ibn Suleyman frequents, to drug him with the black lotos. Then I would do my work on him. It’s much like hypnotism.

“The owner of the joint must have talked. Anyway, Erlik Khan learned how I’d been using Ali ibn Suleyman, and he decided to punish me. Maybe he was afraid the Druse talked too much while he was drugged.

“I know too much, too, for one not sworn to obey Erlik Khan. I’m part Oriental and I’ve played in the fringe of River Street affairs until I’ve got myself tangled up in them. Josef played with fire, too, just as I’ve been doing, and it cost him his life. Erlik Khan told me tonight who the real murderer was. It was Osman Pasha. He wasn’t aiming at you. He intended to kill Josef.

“I’ve been a fool, and now my life is forfeit. Erlik Khan is the king of River Street.”

“He won’t be long,” growled the detective. “We’re going to get out of here some how, and then I’m coming back with a squad and clean out this damned rat hole. I’ll show Erlik Khan that this is America, not Mongolia. When I get through with him—”

He broke off short as Joan’s fingers closed on his convulsively. From somewhere below them sounded a confused muttering. What lay above, he had no idea, but his skin crawled at the thought of being trapped on that dark twisting stair. He hurried, almost dragging the girl, and presently encountered a door that did not seem to be locked.

Even as he did so, a light flared below, and a shrill yelp galvanized him. Far below he saw a cluster of dim shapes in a red glow of a torch or lantern. Rolling eyeballs flashed whitely, steel glimmered.

Darting through the door and slamming it behind them, he sought for a frenzied instant for a key that would fit the lock and not finding it, seized Joan’s wrist and ran down the corridor that wound among black velvet hangings. Where it led he did not know. He had lost all sense of direction. But he did know that death grim and relentless was on their heels.

Looking back, he saw a hideous crew swarm up into the corridor: yellow men in silk jackets and baggy trousers, grasping knives. Ahead of him loomed a curtain-hung door. Tearing aside the heavy satin hangings, he hurled the door open and leaped through, drawing Joan after him, slamming the door behind them. And stopped dead, an icy despair gripping at his heart.

They had come into a vast hall-like chamber, such as he had never dreamed existed under the prosaic roofs of any Western city.

Gilded lanterns, on which writhed fantastic carven dragons, hung from the fretted ceiling, shedding a golden lustre over velvet hangings that hid the walls. Across these black expanses other dragons twisted, worked in silver, gold and scarlet. In an alcove near the door reared a squat idol, bulky, taller than a man, half hidden by a heavy lacquer screen, an obscene, brutish travesty of nature, that only a Mongolian brain could conceive. Before it stood a low altar, whence curled up a spiral of incense smoke.

But Harrison at the moment gave little heed to the idol. His attention was riveted on the robed and hooded form which sat cross-legged on a velvet divan at the other end of the hall—they had blundered full into the web of the spider. About Erlik Khan in subordinate attitudes sat a group of Orientals, Chinese, Syrians and Turks.

The paralysis of surprize that held both groups was broken by a peculiarly menacing cry from Erlik Khan, who reared erect, his hand flying to his girdle. The others sprang up, yelling and fumbling for weapons. Behind him, Harrison heard the clamor of their pursuers just beyond the door. And in that instant he recognized and accepted the one desperate alternative to instant capture. He sprang for the idol, thrust Joan into the alcove behind it, and squeezed after her. Then he turned at bay. It was the last stand—trail’s end. He did not hope to escape; his motive was merely that of a wounded wolf which drags itself into a corner where its killers must come at it from in front.

The green stone bulk of the idol blocked the entrance of the alcove save for one side, where there was a narrow space between its misshapen hip and shoulder, and the corner of the wall. The space on the other side was too narrow for a cat to have squeezed through, and the lacquer screen stood before it. Looking through the interstices of this screen, Harrison could see the whole room, into which the pursuers were now storming. The detective recognized their leader as Fang Yim, the hatchet-man.

A furious babble rose, dominated by Erlik Khan’s voice, speaking English, the one common language of those mixed breeds.

“They hide behind the god; drag them forth.”

“Let us rather fire a volley,” protested a dark-skinned powerfully built man whom Harrison recognized—Ak Bogha, a Turk, his fez contrasting with his full dress suit. “We risk our lives, standing here in full view; he can shoot through that screen.”

“Fool!” The Mongol’s voice rasped with anger. “He would have fired already if he had a gun. Let no man pull a trigger. They can crouch behind the idol, and it would take many shots to smoke them out. We are not now in the Crypts of Silence. A volley would make too much noise; one shot might not be heard in the streets. But one shot will not suffice. He has but an axe; rush in and cut him down!”

Without hesitation Ak Bogha ran forward, followed by the others. Harrison shifted his grip on his axe haft. Only one man could come at him at a time—

Ak Bogha was in the narrow strait between idol and wall before Harrison moved from behind the great green bulk. The Turk yelped in fierce triumph and lunged, lifting his knife. He blocked the entrance; the men crowding behind him had only a glimpse, over his straining shoulder, of Harrison’s grim face and blazing eyes.

Full into Ak Bogha’s face Harrison thrust the axe head, smashing nose, lips and teeth. The Turk reeled, gasping and choking with blood, and half blinded, but struck again, like the slash of a dying panther. The keen edge sliced Harrison’s face from temple to jaw, and then the flailing axe crushed in Ak Bogha’s breastbone and sent him reeling backward, to fall dying.

The men behind him gave back suddenly. Harrison, bleeding like a stuck hog, again drew back behind the idol. They could not see the white giant who lurked at bay in the shadow of the god, but they saw Ak Bogha gasping his life out on the bloody floor before the idol, like a gory sacrifice, and the sight shook the nerve of the fiercest.

And now, as matters hovered at a deadlock, and the Lord of the Dead seemed himself uncertain, a new factor introduced itself into the tense drama. A door opened and a fantastic figure swaggered through. Behind him Harrison heard Joan gasp incredulously.

It was Ali ibn Suleyman who strode down the hall as if he trod his own castle in the mysterious Djebel Druse. No longer the garments of western civilization clothed him. On his head he wore a silken kafiyeh bound about the temples with a broad gilded band. Beneath his voluminous, girdled abba showed silver-heeled boots, ornately stitched. His eye-lids were painted with kohl, causing his eyes to glitter even more lethally than ordinarily. In his hand was a long curved scimitar.

Harrison mopped the blood from his face and shrugged his shoulders. Nothing in the house of Erlik Khan could surprize him any more, not even this picturesque shape which might have just swaggered out of an opium dream of the East.

The attention of all was centered on the Druse as he strode down the hall, looking even bigger and more formidable in his native costume than he had in western garments. He showed no more awe of the Lord of the Dead than he showed of Harrison. He halted directly in front of Erlik Khan, and spoke without meekness.

“Why was it not told me that mine enemy was a prisoner in the house?” he demanded in English, evidently the one language he knew in common with the Mongol.

“You were not here,” Erlik Khan answered brusquely, evidently liking little the Druse’s manner.

“Nay, I but recently returned, and learned that the dog who was once Ahmed Pasha stood at bay in this chamber. I have donned my proper garb for this occasion.” Turning his back full on the Lord of the Dead, Ali ibn Suleyman strode before the idol.

“Oh, infidel!” he called, “come forth and meet my steel! Instead of the dog’s death which is your due, I offer you honorable battle—your axe against my sword. Come forth, ere I hale you thence by your beard!”

“I haven’t any beard,” grunted the detective. “Come in and get me!”

“Nay,” scowled Ali ibn Suleyman; “when you were Ahmed Pasha, you were a man. Come forth, where we can have room to wield our weapons. If you slay me, you shall go free. I swear by the Golden Calf!”

“Could I dare trust him?” muttered Harrison.

“A Druse keeps his word,” whispered Joan. “But there is Erlik Khan—”

“Who are you to make promises?” called Harrison. “Erlik Khan is master here.”

“Not in the matter of my private feud!” was the arrogant reply. “I swear by my honor that no hand but mine shall be lifted against you, and that if you slay me, you shall go free. Is it not so, Erlik Khan?”

“Let it be as you wish,” answered the Mongol, spreading his hands in a gesture of resignation.

Joan grasped Harrison’s arm convulsively, whispering urgently: “Don’t trust him! He won’t keep his word! He’ll betray you and Ali both! He’s never intended that the Druse should kill you—it’s his way of punishing Ali, by having some one else kill you! Don’t—don’t—”

“We’re finished anyway,” muttered Harrison, shaking the sweat and blood out of his eyes. “I might as well take the chance. If I don’t they’ll rush us again, and I’m bleeding so that I’ll soon be too weak to fight. Watch your chance, girl, and try to get away while everybody’s watching Ali and me.” Aloud he called: “I have a woman here, Ali. Let her go before we start fighting.”

“To summon the police to your rescue?” demanded Ali. “No! She stands or falls with you. Will you come forth?”

“I’m coming,” gritted Harrison. Grasping his axe, he moved out of the alcove, a grim and ghastly figure, blood masking his face and soaking his torn garments. He saw Ali ibn Suleyman gliding toward him, half crouching, the scimitar in his hand a broad curved glimmer of blue light. He lifted his axe, fighting down a sudden wave of weakness—there came a muffled dull report, and at the same instant he felt a paralyzing impact against his head. He was not aware of falling, but realized that he was lying on the floor, conscious but unable to speak or move.

A wild cry rang in his dulled ears and Joan La Tour, a flying white figure, threw herself down beside him, her fingers frantically fluttering over him.

“Oh, you dogs, dogs!” she was sobbing. “You’ve killed him!” She lifted her head to scream: “Where is your honor now, Ali ibn Suleyman?”

From where he lay Harrison could see Ali standing over him, scimitar still poised, eyes flaring, mouth gaping, an image of horror and surprize. And beyond the Druse the detective saw the silent group clustered about Erlik Khan; and Fang Yim was holding an automatic with a strangely misshapen barrel—a Maxim silencer. One muffled shot would not be noticed from the street.

A fierce and frantic cry burst from Ali ibn Suleyman.

“Aie, my honor! My pledged word! My oath on the Golden Calf! You have broken it! You have shamed me to an infidel! You robbed me both of vengeance and honor! Am I a dog, to be dealt with thus! Ya Maruf!”

His voice soared to a feline screech, and wheeling, he moved like a blinding blur of light. Fang Yim’s scream was cut short horribly in a ghastly gurgle, as the scimitar cut the air in a blue flame. The Chinaman’s head shot from his shoulders on a jetting fountain of blood and thudded on the floor, grinning awfully in the golden light. With a yell of terrible exultation, Ali ibn Suleyman leapt straight toward the hooded shape on the divan. Fezzed and turbaned figures ran in between. Steel flashed, showering sparks, blood spurted, and men screamed. Harrison saw the Druse scimitar flame bluely through the lamplight full on Erlik Khan’s coifed head. The hood fell in halves, and the Lord of the Dead rolled to the floor, his fingers convulsively clenching and unclenching.

The others swarmed about the maddened Druse, hacking and stabbing. The figure in the wide-sleeved abba was the center of a score of licking blades, of a gasping, blaspheming, clutching knot of straining bodies. And still the dripping scimitar flashed and flamed, shearing through flesh, sinew and bone, while under the stamping feet of the living rolled mutilated corpses. Under the impact of struggling bodies, the altar was overthrown, the smoldering incense scattered over the rugs. The next instant flame was licking at the hangings. With a rising roar and a rush the fire enveloped one whole side of the room, but the battlers heeded it not.

Harrison was aware that someone was pulling and tugging at him, someone who sobbed and gasped, but did not slacken their effort. A pair of slender hands were locked in his tattered shirt, and he was being dragged bodily through billowing smoke that blinded and half strangled him. The tugging hands grew weaker, but did not release their hold, as their owner fought on in a heart-breaking struggle. Then suddenly the detective felt a rush of clean wind, and was aware of concrete instead of carpeted wood under his shoulders.

He was lying in a slow drizzle on a sidewalk, while above him towered a wall reddened in a mounting glare. On the other side loomed broken docks, and beyond them the lurid glow was reflected on water. He heard the screams of fire sirens, and felt the gathering of a chattering, shouting crowd about him.

Life and movement slowly seeping back into his numbed veins, he lifted his head feebly, and saw Joan La Tour crouched beside him, oblivious to the rain as to her scanty attire. Tears were streaming down her face, and she cried out as she saw him move: “Oh, you’re not dead—I thought I felt life in you, but I dared not let them know—”

“Just creased my scalp,” he mumbled thickly. “Knocked me out for a few minutes—seen it happen that way before—you dragged me out—”

“While they were fighting. I thought I’d never find an outer door—here come the firemen at last!”

“The Yat Soys!” he gasped, trying to rise. “Eighteen Chinamen in that basement—my God, they’ll be roasted!”

“We can’t help it!” panted Joan La Tour. “We were fortunate to save ourselves. Oh!”

The crowd surged back, yelling, as the roof began to cave in, showering sparks. And through the crumpling walls, by some miracle, reeled an awful figure—Ali ibn Suleyman. His clothing hung in smoldering, bloody ribbons, revealing the ghastly wounds beneath. He had been slashed almost to pieces. His head-cloth was gone, his hair crisped, his skin singed and blackened where it was not blood-smeared. His scimitar was gone, and blood streamed down his arm over the fingers that gripped a dripping dagger.

“Aie!” he cried in a ghastly croak. “I see you, Ahmed Pasha, through the fire and mist! You live, in spite of Mongol treachery! That is well! Only by the hand of Ali ibn Suleyman, who was Amir Amin Izzedin, shall you die! I have washed my honor in blood, and it is spotless!

“I am a son of Maruf,

Of the mountain of sanctuary;

When my sword is rusty

I make it bright

With the blood of my enemies!”

Reeling, he pitched face first, stabbing at Harrison’s feet as he fell; then rolling on his back he lay motionless, staring sightlessly up at the flame-lurid skies.