Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

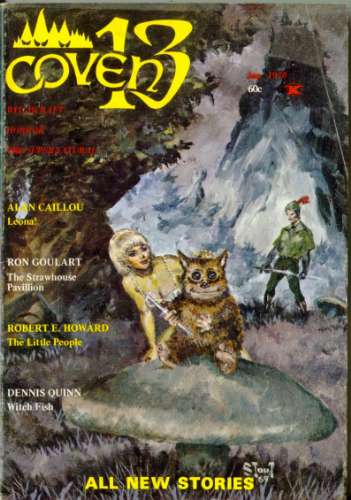

Published in Coven 13, Vol. 1, No. 3 (January 1970).

My sister threw down the book she was reading. To be exact, she threw it at me.

“Foolishness!” said she. “Fairy tales! Hand me that copy of Michael Arlen.”

I did so mechanically, glancing at the volume which had incurred her youthful displeasure. The story was “The Shining Pyramid” by Arthur Machen.

“My dear girl,” said I, “this is a masterpiece of outre literature.”

“Yes, but the idea!” she answered. “I outgrew fairy tales when I was ten.”

“This tale is not intended as an exponent of common-day realism,” I explained patiently.

“Too far-fetched,” she said with the finality of seventeen. “I like to read about things that could happen—who were ‘The Little People’ he speaks of, the same old elf and troll business?”

“All legends have a base of fact,” I said. “There is a reason—”

“You mean to tell me such things actually existed?” she exclaimed. “Rot!”

“Not so fast, young lady,” I admonished, slightly nettled. “I mean that all myths had a concrete beginning which was later changed and twisted so as to take on a supernatural significance. Young people,” I continued, bending a brotherly frown on her pouting lips, “have a way of either accepting entirely or rejecting entirely such things as they do not understand. The ‘Little People’ spoken of by Machen are supposed to be descendants of the prehistoric people who inhabited Europe before the Celts came down out of the North.

“They are known variously as Turanians, Picts, Mediterraneans, and Garlic-eaters. A race of small, dark people, traces of their type may be found in primitive sections of Europe and Asia today, among the Basques of Spain, the Scotch of Galloway and the Lapps.

“They were workers in flint and are known to anthropologists as men of the Neolithic or polished stone age. Relics of their age show plainly that they had reached a comparatively high stage of primitive culture by the beginning of the bronze age, which was ushered in by the ancestors of the Celts—our prehistoric tribesmen, young lady.

“These destroyed or enslaved the Mediterranean peoples and were in turn ousted by the Teutonic tribes. All over Europe, and especially in Britain, the legend is that these Picts, whom the Celts looked upon as scarcely human, fled to caverns under the earth and lived there, coming out only at night, when they would burn, murder, and carry off children for their bloody rites of worship. Doubtless there was much in this theory. Descendants of cave people, these fleeing dwarfs would no doubt take refuge in caverns and no doubt managed to live undiscovered for generations.”

“That was a long time ago,” she said with slight interest. “If there ever were any of those people they’re dead now. Why, we’re right in the country where they’re supposed to perform and haven’t seen any signs of them.”

I nodded. My sister Joan did not react to the weird West country as I did. The immense menhirs and cromlechs which rose starkly upon the moors seemed to bring back vague, racial memories, stirring my Celtic imagination.

“Maybe,” I said, adding unwisely, “You heard what that old villager said—the warning about walking on the fen at night. No one does it. You’re very sophisticated, young lady, but I’ll bet you wouldn’t spend a night alone in that stone ruin we can see from my window.”

Down came her book and her eyes sparkled with interest and combat.

“I’ll do it!” she exclaimed. “I’ll show you! He did say no one would go near those old rocks at night, didn’t he? I will, and stay there the rest of the night!”

She was on her feet instantly and I saw I had made a mistake.

“No, you won’t, either,” I vetoed. “What would people think?”

“What do I care what they think?” she retorted in the up to date spirit of the Younger Generation.

“You haven’t any business out on the moors at night,” I answered. “Granting that these old myths are so much empty wind, there are plenty of shady characters who wouldn’t hesitate to harm a helpless girl. It’s not safe for a girl like you to be out unprotected.”

“You mean I’m too pretty?” she asked naively.

“I mean you’re too foolish,” I answered in my best older brother manner.

She made a face at me and was silent for a moment and I, who could read her agile mind with absurd ease, could tell by her pensive features and sparkling eyes exactly what she was thinking. She was mentally surrounded by a crowd of her cronies back home and I could guess the exact words which she was already framing: “My dears, I spent a whole night in the most romantic old ruin in West England which was supposed to be haunted—”

I silently cursed myself for bringing the subject up when she said abruptly, “I’m going to do it, just the same. Nobody will harm me and I wouldn’t pass up the adventure for anything!”

“Joan,” I said, “I forbid you to go out alone tonight or any other night.”

Her eyes flashed and I instantly wished I had couched my command in more tactful language. My sister was willful and high spirited, used to having her way and very impatient of restraint.

“You can’t order me around,” she flamed. “You’ve done nothing but bully me ever since we left America.”

“It’s been necessary,” I sighed. “I can think of a number of pastimes more pleasant than touring Europe with a flapper sister.”

Her mouth opened as if to reply angrily then she shrugged her slim shoulders and settled back down in her chair, taking up a book.

“Alright, I didn’t want to go much anyhow,” she remarked casually. I eyed her suspiciously; she was not usually subdued so easily. In fact some of the most harrowing moments of my life have been those in which I was forced to cajole and coax her out of a rebellious mood.

Nor was my suspicion entirely vanquished when a few moments later she announced her intention of retiring and went to her room just across the corridor.

I turned out the light and stepped over to my window, which opened upon a wide view of the barren, undulating wastes of the moor. The moon was just rising and the land glimmered grisly and stark beneath its cold beams. It was late summer and the air was warm, yet the whole landscape looked cold, bleak and forbidding. Across the fen I saw rise, stark and shadowy, the rough and mighty spires of the ruins. Gaunt and terrible they loomed against the night, silent phantoms from

[A page appears to be missing from Howard’s typescript here.]

she assented with no enthusiasm and returned my kiss in a rather perfunctory manner. Compulsory obedience was repugnant.

I returned to my room and retired. Sleep did not come to me at once however, for I was hurt at my sister’s evident resentment and I lay for a long time, brooding and staring at the window, now framed boldly in the molten silver of the moon. At length I dropped into a troubled slumber, through which flitted vague dreams wherein dim, ghostly shapes glided and leered.

I awoke suddenly, sat up and stared about me wildly, striving to orient my muddled senses. An oppressive feeling as of impending evil hovered about me. Fading swiftly as I came to full consciousness, lurked the eery remembrance of a hazy dream wherein a white fog had floated through the window and had assumed the shape of a tall, white bearded man who had shaken my shoulder as if to arouse me from sleep. All of us are familiar with the curious sensations of waking from a bad dream—the dimming and dwindling of partly remembered thoughts and feelings. But the wider awake I became, the stronger grew the suggestion of evil.

I sprang up, snatched on my clothing and rushed to my sister’s room, flung open the door. The room was unoccupied.

I raced down the stair and accosted the night clerk who was maintained by the small hotel for some obscure reason.

“Miss Costigan, sir? She came down, clad for outdoors, a while after midnight—about half an hour ago, sir, and said she was going to take a stroll on the moor and not to be alarmed if she did not return at once, sir.”

I hurled out of the hotel, my pulse pounding a devil’s tattoo. Far out across the fen I saw the ruins, bold and grim against the moon, and in that direction I hastened. At length—it seemed hours—I saw a slim figure some distance in front of me. The girl was taking her time and in spite of her start of me, I was gaining—soon I would be within hearing distance. My breath was already coming in gasps from my exertions but I quickened my pace.

The aura of the fen was like a tangible something, pressing upon me, weighting my limbs—and always that presentiment of evil grew and grew.

Then, far ahead of me, I saw my sister stop suddenly, and look about her confusedly. The moonlight flung a veil of illusion—I could see her but I could not see what had caused her sudden terror. I broke into a run, my blood leaping wildly and suddenly freezing as a wild, despairing scream burst out and sent the moor echoes flying.

The girl was turning first one way and then another and I screamed for her to run toward me; she heard me and started toward me running like a frightened antelope and then I saw. Vague shadows darted about her—short, dwarfish shapes—just in front of me rose a solid wall of them and I saw that they had blocked her from gaining to me. Suddenly, instinctively I believe, she turned and raced for the stone columns, the whole horde after her, save those who remained to bar my path.

I had no weapon nor did I feel the need of any; a strong, athletic youth, I was in addition an amateur boxer of ability, with a terrific punch in either hand. Now all the primal instincts surged redly within me; I was a cave man bent on vengeance against a tribe who sought to steal a woman of my family. I did not fear—I only wished to close with them. Aye, I recognized these—I knew them of old and all the old wars rose and roared within the misty caverns of my soul. Hate leaped in me as in the old days when men of my blood came from the North. Aye, though the whole spawn of Hell rise up from those caverns which honeycomb the moors.

Now I was almost upon those who barred my way; I saw plainly the stunted bodies, the gnarled limbs, the snake-like, beady eyes that stared unwinkingly, the grotesque, square faces with their unhuman features, the shimmer of flint daggers in their crooked hands. Then with a tigerish leap I was among them like a leopard among jackals and details were blotted out in a whirling red haze. Whatever they were, they were of living substance; features crumpled and bones shattered beneath my flailing fists and blood darkened the moon-silvered stones. A flint dagger sank hilt deep in my thigh. Then the ghastly throng broke each way and fled before me, as their ancestors fled before mine, leaving four silent dwarfish shapes stretched on the moor.

Heedless of my wounded leg, I took up the grim race anew; Joan had reached the druidic ruins now and she leaned against one of the columns, exhausted, blindly seeking there protection in obedience to some dim instinct just as women of her blood had done in bygone ages.

The horrid things that pursued her were closing in upon her. They would reach her before I. God knows the thing was horrible enough but back in the recesses of my mind, grimmer horrors were whispering; dream memories wherein stunted creatures pursued white limbed women across such fens as these. Lurking memories of the ages when dawns were young and men struggled with forces which were not of men.

The girl toppled forward in a faint, and lay at the foot of the towering column in a piteous white heap. And they closed in—closed in. What they would do I knew not but the ghosts of ancient memory whispered that they would do Something of hideous evil, something foul and grim.

From my lips burst a scream, wild and inarticulate, born of sheer elemental horror and despair. I could not reach her before those fiends had worked their frightful will upon her. The centuries, the ages swept back. This was as it had been in the beginning. And what followed, I know not how to explain—but I think that that wild shriek whispered back down the long reaches of Time to the Beings my ancestors worshipped and that blood answered blood. Aye, such a shriek as could echo down the dusty corridors of lost ages and bring back from the whispering abyss of Eternity the ghost of the only one who could save a girl of Celtic blood.

The foremost of the Things were almost upon the prostrate girl; their hands were clutching for her, when suddenly beside her a form stood. There was no gradual materializing. The figure leaped suddenly into being, etched bold and clear in the moonlight. A tall white bearded man, clad in long robes—the man I had seen in my dream! A druid, answering once more the desperate need of people of his race. His brow was high and noble, his eyes mystic and far-seeing—so much I could see, even from where I ran. His arm rose in an imperious gesture and the Things shrank back—back—back—They broke and fled, vanishing suddenly, and I sank to my knees beside my sister, gathering the child into my arms. A moment I looked up at the man, sword and shield against the powers of darkness, protecting helpless tribes as in the world’s youth, who raised his hand above us as if in benediction, then he too vanished suddenly and the moor lay bare and silent.