Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

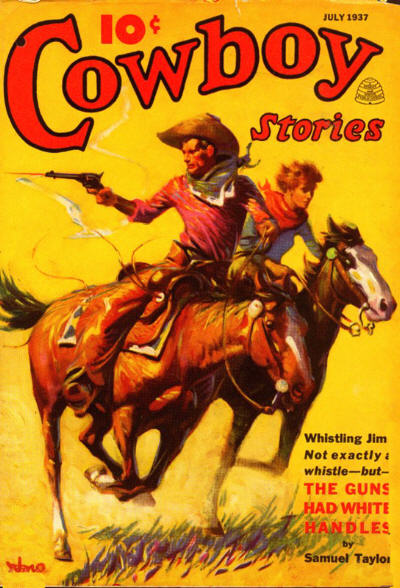

Published in Cowboy Stories, July 1937.

I had just sot down on my bunk and was fixing to pull off my boots, when Pap come out of the back room and blinked at the candle which was stuck onto the table.

Says he, “Well, Buckner, is they anything new over to Knife River?”

“They ain’t never nothin’ new there,” I says, yawning. “They’s a new gal slingin’ hash in the Royal Grand resternt, but Bill Hopkins has already got hisself engaged to her, and ’lows he’ll shoot anybody which so much as looks at her. They was a big poker game in back of the Golden Steer and Tunk winned seventy bucks and got carved with a bowie.”

“The usual derned foolishness,” grumbled Pap, turning around to go back to bed. “When I was a young buck, they was always excitement to be found in town—pervidin’ you could find a town.”

“Oh, yes,” I says suddenly. “I just happened to remember. I shot a feller in the Diamond Palace Saloon.”

Pap turned around and combed his beard with his fingers.

“Gittin’ a mite absent-minded, ain’t you, Buckner?” says he. “Did they identify the remains?”

“Aw, I didn’t croak him,” says I. “I just kinda shot him through the shoulder and a arm and the hind leg. He was a stranger in these here parts, and I thought maybe he didn’t know no better.”

“No better’n what?” demanded Pap. “What was the argyment?”

“I don’t remember,” I confessed. “It was somethin’ about politics.”

“What you know about politics?” snorted Pap.

“Nothin’,” I says. “That’s why I plugged him. I run out of argyments.”

“Daw-gone it, Buckner,” says Pap, “you got to be a little more careful how you go around shootin’ people in saloons. This here country is gittin’ civilized, what with britch-loadin’ guns, and stagecoaches and suchlike. I don’t hold with these here newfangled contraptions, but lots of people does, and the majority rules—les’n yo’re quicker on the draw than what they be.

“Now you done got the family into trouble again. You’ll have that ranger, Kirby, onto yore neck. Don’t you know he’s in this here country swearin’ he’s goin’ to bring in law and order if he has to smoke up every male citizen of Knife River County? If any one man can do it, he can, because he’s the fastest gunman between the Guadalupe and the Rio Grande. More’n that, it ain’t just him. He’s got the whole ranger force behind him. The Grimes family has fit their private feuds as obstreperous as anybody in the State of Texas. But we ain’t buckin’ the rangers. And what we goin’ to do now when Kirby descends on us account of yore action?”

“I don’t think he’s goin’ to descend any time soon, Pap,” I says.

“When I wants yore opinion I’ll ast for it!” Pap roared. “Till then, shut up! Why don’t you think he will?”

“ ’Cause Kirby was the feller I shot,” I says.

Pap stood still a while, combing his whiskers, with a most curious expression; then he laid hold onto my collar and the seat of my britches and begun to walk me toward the door.

“The time has come, Buckner,” says he, “for you to go forth and tackle the world on yore own. Yo’re growed in height, if not in bulk and mentality, and anyway, as I remarked while ago, the welfare of the majority has got to be considered. The Grimes family is noted for its ability to soak up punishment, but they’s a limit to everything. When I recalls the family feuds, gunfights and range wars yore mental incapacity and lack of discretion has got us into ever since you was big enough to sight a gun, I looks with no enthusiasm onto a pitched battle with the rangers and probably the State milishy. No, Buckner, I think you better hit out for foreign parts.”

“Where you want me to go, Pap?” I inquired.

“Californy,” he answered, kicking the door open.

“Why Californy?” I asked.

“Because that’s the fartherest-off place I can think of,” he says, lifting me through the door with the toe of his boot. “Go with my blessin’!”

I pulled my nose out of the dirt and got up and hollered through the door which Pap had locked and bolted on the inside, “How long I oughta stay?”

“Not too long,” says Pap. “Don’t forgit yore pore old father and yore other relatives which will grieve for you. Come back in about forty or fifty years.”

“Where ’bouts is Californy?” I asked.

“It’s where they git gold,” he says. “If you ride straight west long enough yo’re bound to git there eventually.”

I went out to the corral and saddled my horse—or rather, I saddled my brother Jim’s horse—because his’n was better’n mine—and I hit out, feeling kinda funny, because I hadn’t never been away from home no farther’n the town of Knife River. I couldn’t head due west on account of that route would ’a’ took me across “Old Man” Gordon’s ranch, and he had give his punchers orders to shoot me on sight, account of me smoking up his three boys at a dance a few months before.

So I swung south till I got as near the Donnellys’ range as I felt like I oughta, what with Joe Donnelly still limping on a crutch from a argyment him and me had in Knife River. So I turned west again and hit straight through the settlement of Broken Rope. None of the nine or ten citizens which was gunning for me was awake, so I rode peacefully through and headed into unknown country just as the sun come up.

Well, for a long time I rode through country which was inhabited very seldom. After I left the settlements on Knife River, there was a long stretch in which about the only folks I seen was Mexican sheep-herders which I was ashamed to ask ’em where I was, for fear they’d think I was ignerunt. Then even the sheep-herders played out, and I crossed some desert that me and Brother Jim’s horse nearly starved on, but I knowed that if I kept heading west I’d fetch Californy finally.

So I rode for days and days and finally got into better-looking country again, and I decided I must be there, because I didn’t see how anything could be any further from anything else than what I’d come. I was homesick and low in my spirits, and would ’a’ sold my hopes of the future for ten cents.

Well, finally one day, along about the middle of the morning, I found myself in a well-watered, hilly country, a little like that around Knife River, only with the hills bigger, and they was right smart rocks. So I thought to myself, “I’m good and tired of this here perambulatin’; I’m goin’ to stop right here and mine me some gold.” I’d heard tell they found gold in rocks. So I tied brother Jim’s horse to a tree, and I located me a likely boulder beside the trail, about as big as a barn, and begun knocking chips off it with a hunk of flint.

I was making so much noise I didn’t hear the horses coming up the trail, and the first thing I knowed I wasn’t alone.

Somebody said, “What in tarnation are you doin’?”

I turned around and there was a gang of five men on horses, hard-looking gents with skins about the color of old leather, and the biggest one was nigh as dark as a Indian with drooping whiskers. He twist these whiskers and scowled, and says, “Didn’t you hear me? What you bustin’ chunks off that rock for?”

“I’m prospectin’ for gold,” I says. He kinda turned purple, and his eyes got red and he snorted through his whiskers and says, “Don’t you try to make no fool outa William Hyrkimer Hawkins! The boundless prairies is dotted with the bones of such misguided idjits. I ast you a civil question—”

“I done told you,” I said. “I’m huntin’ me some gold. I heard tell they git it outa rocks.”

He looked kinda stunned, and the men behind him haw-hawed and said, “Don’t shoot him, Bill, the blame hillbilly is on the level.”

“By golly,” he said, twisting his mustash, “I believe it. But he ain’t no hillbilly. Who’re you, and where you from, and where you goin’?”

“I’m Buckner Jeopardy Grimes,” I says. “I’m from Knife River County, Texas, and I’m on my way to the gold fields of Californy.”

“Well,” says he, “you still got a long way to go.”

“Ain’t this Californy?” I says.

He says, “Naw, this here is New Mexico. Come on. We’re ridin’ to Smokeville. Climb on yore cayuse and trail with us.”

“What you want this gangle-legged waddy grazin’ around with us for?” demanded one of the fellers.

“He’s good for a laugh,” said Hawkins.

“If you like yore humor mixed up with gun smoke,” opined a bald-headed old cuss which looked like a pessimistic timber wolf. “I’ve seen a lot of hombres outa Texas, and some was smart and some was dumb, but they was all alike in one respect: they was all pizen.”

Hawkins snorted and I mounted onto my brother Jim’s horse and we started for Smokeville, wherever that was. They was four men and Hawkins, and they called thereselves “Squint” and “Red” and “Curly” and “Arizona,” and next to some of my relatives on Knife River, they was the toughest-looking gang of thugs I ever seen in my life.

Then after a while we come in sight of Smokeville. It wasn’t as big as Knife River, but it had about as many saloons. They rode into town at a dead run, hollering and shooting off their pistols. I rode with ’em because I wanted to be polite, but I didn’t celebrate none, because I was a long ways from home and low in my spirits.

All the folks taken to cover, and Hawkins rode his horse up on the porch of a saloon. There was a piece of paper tacked on the wall.

His men says, “What does it say, Bill? Read it to us!”

So he spit his tobaccer out on the porch, and read:

Us citizens of Smokeville has passed the follerin’ laws which we aims to see enforced to the full extent of fines and imprisonment and being plugged with a .45 for resistin’ arrest. It’s agin’ the law to shoot off pistols in saloons and resternts; it’s agin’ the law for gents to shoot each other inside the city limits; it’s agin’ the law to ride horses into saloons and shoot buttons off the bartender’s coat. Signed: us citizens of Smokeville and Joe Clanton, sheriff.

Hawkins roared like a bull looking at a red bandanner.

“What air we a-comin’ to?” he bellered. “What kind of a government air we livin’ under? Air we men or air we jassacks? Is they no personal liberty left no more?”

“I dunno,” I said. “I never heered of no such laws back in Texas.”

“I warn’t talkin’ to you, you long-legged road-runner!” he snorted, ripping the paper off the wall. “Foller me, boys. We’ll show ’em they can’t tromple on the rights of free-born white men!”

So they surged into the saloon on their horses and the bartender run out the back way hollering, “Run, everybody! Hawkins is back in town!”

So the feller they called Squint got behind the bar and started servin’ the drinks. They all got off of their cayuses so’s they could drink easier, and Hawkins told me to take the horses out and tie ’em to the hitching rack.

I done it, and when I got back they’d dragged the sheriff out from under the bar where he was hiding, and was making him eat the paper Hawkins had tore off the wall. He was a fat man with a bald head and a pot belly, and they’d tooken his gun away, which he hadn’t tried to use.

“A fine specimen you be!” said Hawkins fiercely, sticking his gun muzzle outa sight in the sheriff ’s quivering belly. “I oughta shoot you! Tryin’ to persecute honest men! Tryin’ to crush human liberty under the mailed fist of oppressive laws! Sheriff ! Bah! We impeaches you!” He jerked off Clanton’s star and kicked him heartily in the pants. “Git out! You ain’t sheriff no more’n a jack rabbit.” Clanton made for the door like he had wasps in his britches, and they shot the p’ints off his spurs as he run.

“The nerve of these coyotes!” snorted Hawkins, downing about a quart of licker at a snort and throwing the bottle through the nearest glass winder. “Sheriff ! Ha!” He glared around till he spied me. Then he grinned like a timber wolf, and says, “Come here, you! I make you sheriff of Smokeville!” And he stuck the badge on my shirt, and everybody haw-hawed and shot their pistols through the roof.

I said, “I ain’t never done no sheriffin’ before. What am I supposed to do?”

“The first thing is to set up drinks for the house,” said Red.

I said, “I ain’t got but a dollar.”

And Hawkins said, “Don’t be a sap. None of my men ever pays for anything they get in Smokeville. I got a pocketful of money right now, but you don’t see me handin’ out none to these sissies, does you?”

So I said, “Oh, all right then, the drinks is on me.”

And everybody yelled and hollered and shot holes in the mirror behind the bar and guzzled licker till it was astonishing to behold. After a while they scattered up and down the street, some into other saloons, and some into a dance hall.

So I taken brother Jim’s horse down to the wagon yard and told the man to take care of him.

He looked at my badge very curious, but said he’d do it.

So I said, “I understand none of Mr. Hawkins’ men has to pay for nothin’ in Smokeville. Is that right?”

He kinda shivered and said that Mr. Hawkins was such a credit to the country that nobody had the heart to charge him for anything, and them which had was not now in the land of the living.

Well, this all seemed very strange to me, but Pap once told me that when I got outa Texas I would find folks in other parts had different customs. So I went back up the street. Hawkins’ gang was still raising hell and very few folks was in sight. I never seen people so scared of five men in my life. I seen a resternt up toward the east end of the street, and I was hungry and went in. They was a awful purty gal in there.

I would ’a’ beat a retreat, because I was awful bashful and scared of gals, but she seen me and kinda turned pale, and said, “What—what do you want?”

So I taken off my hat, and said, “I would like a steak and some aigs and ’taters and a few molasses if it ain’t too much trouble, please, ma’am.”

So I sot down and she went to work and slung the stuff together, and purty soon she looked at me kinda apprehensive, and says, “How—how long are you men going to stay in Smokeville?”

I said I jedged the gents would stay till all the whisky was gone, which wouldn’t be long at the rate they was demolishing it, and I says, “You’re a foreigner, ain’t you, miss?”

And she says, “Why do you ask?”

“Well,” I says, “I ain’t never hear nobody talk like that before.”

“I am from New York,” she says.

So I says, “Where at is that?”

She says, “It’s away back East.”

“Oh,” I says, “it must be somewheres on t’other side of the Guadalupe.”

She just hove a sigh and shaken her head like she wished she was back there, and just then in come a old codger, with whiskers, which sot down and likewise hove a sigh, clean up from his boot tops. He said, “T’ain’t no use, Miss Joan. I can’t raise the dough. Them thievin’ scoundrels has stole me plumb out. They got the last bunch the other night. All I got on my ranch is critters too old or too sorry for Bill Hawkins to bother to steal—”

She turned pale and whispered, “For Heaven’s sake, be careful, Mr. Garfield; that’s one of Hawkins’ men sitting right there!”

He turned around and seen me, and he turned pale, too, under his whiskers, but he riz up and shaken his fist at me, and said, “Well, you heered what I said, and I ain’t takin’ it back! Bill Hawkins is a thief, and all his men air thieves! Everybody in this country knows they’re thieves, only they’re too skeered to say so! Now, go ahead and shoot me! You and yore gang of outlaws has stole me out and ruined me till I might as well be dead. Well, what you goin’ to do?”

“I’m goin’ to eat this here can of cling peaches if you’ll quit yellin’ at me,” I said, and him and Miss Joan looked astonished, and he sot down and mumbled in his beard and she looked sorry for him and for herself, and I et my peaches.

When I got through, I said, “How much I owe you, miss?”

She looked like she’d just saw a ghost and said, “What?”

“How much, please, ma’am,” I said.

She said, “I never heard of one of Hawkins’ men paying for anything—but it’s a dollar, if yo’re not kidding me.”

I laid down my dollar, and just then somebody shot off their gun outside. In come Hawkins’ man Curly. He was drunk and weaving and he shot his pistol into the roof and yelled, “Gimme some grub and be quick about it!”

Old man Garfield turned white under his whiskers and doubled his fists like he yearned to do somebody vi’lence, and Miss Joan looked scared and started fixing the grub.

Curly seen me and he guffawed, “Howdy, sheriff, you long-legged Texas sage-rooster! Haw! Haw! Haw! That there was the funniest one Bill ever pulled!” So he sot down and breathed whisky fumes all over the place, and when Miss Joan brung his vittles, he grabbed her arm and leered like a cat eating prickly pears, and says, “Gimme a kiss, gal!”

She says, quick and scared, “Let me go! Please let me go!”

I got up then and says, “What you mean by such actions? I never heered of such doins in my life! You release go of her and apolergize!”

“Why, you long, ganglin’ Texas lunkhead!” he yelped, reaching for his gun. “Set down and shet up before I pistol-whips the livin’ daylights outa you!”

So I split open his scalp with my gun barrel, and he fell onto the floor and kicked a few times and layed still. I hauled him to the back door and throwed him down the steps. He fell, head first, into a garbage can which upsot and spilled garbage all over him. He laid there like a hawg in its trough, which was the proper place for him.

“Pap told me other places was different from Texas,” I says fretfully, “but I never had no idee they was this different.”

“I’m getting used to it,” she says with a kinda hard laugh. “The people that live here are good folks, but every time Hawkins and his gang come into town I have to put up with such things as you just saw.”

“How come you ever come out here in the first place?” I asked, because it was just dawning on me that she must be one of them Eastern tenderfoots I’d heard tell of.

“I was tired of slaving in a city,” she said. “I saved my money and came West. When I got to Denver I read an advertisement in a newspaper about a man offering a restaurant for sale in Smokeville, New Mexico. I came here and spent every penny I had on it. It was all right, until Hawkins and his gang started terrorizing the town.”

“I was all set to buy her out,” said old man Garfield mournfully. “I used to be a cook before I was blame fool enough to go into the cattle business. A resternt in Smokeville for my declinin’ years is my idee of heaven—exceptin’ Hawkins and his gang. But I can’t raise the dough. Them thieves has stole me out. Five hundred buys her, and I can’t raise it.”

“Five hundred would get me out of this place and back to some civilized country,” said Miss Joan, with a kind of sob.

I was embarrassed because it always makes me feel bad to see a woman cry. I feel like a yaller dawg, even when it ain’t my fault. I looked down, and all to onst my gaze fell onto the badge which Hawkins had pinned onto my shirt.

“Wait here!” I said suddenly, and I taken old man Garfield by the neck and shoved him down in a chair. “You all stay here till I get back,” I says. “Don’t go no place. I’ll be back right away.”

As I went out the front door, Curly come weaving around the building with egg shells in his ears and ’tater peelings festooned on him, and he was mumbling something about cuckoo clocks and fumbling for his gun. So I hit him under the jaw for good measure and he coiled up under a horse trough and layed there.

I heard a gun banging in the Eagle Saloon, which was about a block west of the resternt, and I went in. Sure enough, Bill Hawkins was striding up and down in solitary grandeur, amusing hisself shooting bottles off the shelves behind the bar.

“Where’s the rest of the fellers?” I asked.

“In the Spanish Bar at the west end of town,” he said. “What’s it to you?”

“Nothin’,” I says.

“Well,” says he, “I’m goin’ to the resternt and make that gal cook me some grub. I’m hungry.”

“I reckon that’s what’s sp’ilin’ yore aim,” I says.

He jumped like he was stabbed and cussed. “What you mean, sp’ilin’ my aim?” he roared.

“Well,” I said, “I seen you miss three of them bottle tops. Back in Texas—”

“Shet up!” he bellered. “I don’t want to hear nothin’ about Texas. You say ‘Texas’ to me just once more and I’ll blow yore brains out.”

“All right,” I said, “but I bet you can’t write yore initials in that mirror behind the bar with yore six-guns.”

“Huh!” he snorted, and begun blazing away with both hands.

“What you quittin’ for?” I asked presently.

“My guns is empty,” he said. “I got to reload.”

“No, you don’t,” I says, shoving my right-hand gun in his belly. “Drop them empty irons!”

He looked as surprised as if a picture had clumb off the wall and bit him.

“What you mean?” he roared. “Is this here yore idee of a joke?”

“Drop them guns and h’ist yore hands,” I commanded.

He turned purple, but he done so, and then dipped and jerked a bowie out of his boot, but I shot it outa his hand before he could straighten. He was white and shaking with rage.

“I arrests you for disturbin’ the peace,” I said.

“What you mean, you arrests me?” he bellered. “You ain’t no sheriff!”

“I am, too,” I said. “You gimme this here badge yoreself. They’s a law against shootin’ holes in saloon mirrors. I tries you and I finds you guilty, and I fines you a fine.”

“How much you fines me?” he asked.

“How much you got?” I asked.

“None of yore cussed business!” he howled.

So I made him turn around with his hands in the air, and I pulled a roll outa his hip pocket big enough to choke a cow.

“This here dough,” I said, “is the money you got from sellin’ the steers you stole from pore old man Garfield. I know, from the remarks yore men let drop while we was ridin’ to Smokeville. Stand still whilst I count it, and don’t try no monkey business.”

So I kept him covered with one hand and counted the dough with the other, and it was slow work, because I hadn’t never seen that much money. But finally I announced, “I fines you five hundred bucks. Here’s the rest.” And I give him back a dollar and fifteen cents.

“You thief !” he howled. “You bandit! You robber! I’ll have yore life for this.”

“Aw, shet up,” I says. “I’m goin’ to lock you up in jail for the night. Some of yore gang can let you out after I’m gone. If I was to let you go now, I’d probably have some trouble with you before I could git outa town.”

“You would!” he asserted bloodthirstily.

“And bein’ a peaceful critter,” I says, jabbing my muzzle into his back, “I takes this here precaution. Git goin’ before I scatters yore remnants all over the floor.”

The jail was a short distance behind the stores and things. I marched him out the back door, and his cussing was something terrible every step of the way. The jail was a small, one-roomed building and a big fat egg was sleeping in the shade. I give him a kick in the pants to wake him up.

He throwed up his hands and yelled, “Don’t shoot! The key’s hangin’ on that nail by the door!” before he got his eyes open.

When he seen me and my prisoner his jaw fell down a foot or so.

“Be you the jailer?” I asked.

“I’m Reynolds, Clanton’s deperty,” he said in a small voice.

“Well,” I says, “onlock that door. We got a prisoner.”

“Wait a minute,” he said. “Ain’t that Bill Hawkins?”

“Sure it is,” I said impatiently. “Hustle, will you?”

“But, gee whiz!” says he. “You ain’t lockin’ up Bill Hawkins!”

“Will you onlock that door and stop gabblin’?” I hollered in exasperation. “You want me to ’rest you for obstructin’ justice?”

“It’s agin’ my better jedgment,” he said, shaking his head as he done my bidding. “It’ll cost us all our lives.”

“And that ain’t no lie!” agreed Hawkins bitterly. But I booted him into the jug, paying no attention to his horrible threats. I told Reynolds to guard him and not let him out till next morning, not on no conditions whatever. Then I headed back up the street for the resternt. Noises of revelry was coming from the Spanish Bar, way down at the west end of the street, and I figgered Hawkins’ braves was still down there.

When I come into the resternt, Miss Joan and old man Garfield was still setting there where I left ’em, looking sorry. I shoved the wad I had took from Hawkins into old man Garfield’s hands, and I says, “Count it!”

He looked dumfounded, but he done so, kind of mechanical, and I says, “How much is they?”

“Five hundred bucks even,” he stuttered.

“That there is right,” I said, yanking the roll out of his hands, and giving it to Miss Joan. “Old man Garfield is now owner of this here hash house. And you got dough enough to go back East.”

“But I don’t understand,” said Miss Joan, kinda dazedly. “Whose money is this?”

“It’s yourn,” I said.

“Hold on,” says old man Garfield. “Ain’t them Bill Hawkins’ ivory-handled guns you got stuck in yore belt?”

“Uh-huh,” I says, laying ’em on the counter. “Why?”

He turned pale and his whiskers curled up and shuddered. “Is that Hawkins’ dough?” he whispered. “Have you croaked him?”

“Naw,” I says. “I ain’t croaked him. He’s in the jail house. And it wasn’t his dough. He just thought it was.”

“I’m too young to die,” quavered old man Garfield. “I knowed they was bound to be a catch in this. You young catamount, don’t you realize that when Hawkins gits outa jail, and finds me ownin’ this resternt, he’ll figger out that I put you up to robbin’ him? He knows I ain’t got no money. You mean well, and I’m plumb grateful, but you done put my aged neck in a sling. He’ll tear this resternt j’int from rafter, and shoot me plumb full of holes.”

“And me!” moaned Miss Joan, turning the color of chalk. “My Lord, what will he do to me?”

I was embarrassed and hitched my gun belt.

“Dawg-gone it,” I says bitterly, “Pap was right. Everything I does is wrong. I never figgered on that. I’ll just have to—”

“Sheriff !” hollered somebody on the outside. “Sheriff!”

Reynolds staggered in with blood streaming from a gash in his head.

“Run, everybody!” he bawled. “Hawkins is out! He pulled the bars outa the winder with his bare hands and hit me on the head with one, and he taken my gun, and he’s headin’ for the Spanish Bar to git his pards and take the town apart! He’s nigh loco he’s so mad, and ravin’ and swearin’ that he’ll burn the town and kill every man in it!”

At that old man Garfield let out a wail of despair, and Miss Joan sank down behind the counter with a moan.

“Le’s take to the hills,” babbled Reynolds. “Clanton’s hidin’ out there somewhere, and—”

“Aw, shet up,” I grunted. “You all stay here. I’m sheriff of this here town, and it’s my job to pertect the citizens. Shet up and set down.”

And, so saying, I hurried out the back door and turned west. As I passed the corner of the building I noticed that Curly was still laying where I left him, being overcome with licker and swats on the dome, though he was showing some signs of life.

I run along behind the backs of the buildings, dodging from one to the other. The Spanish Bar was on the same side of the street as the resternt, so I didn’t have to cross the street to get to it. Evidently, word of the impending massacre must have spread, because the town was perfectly still and tense, except the racket that was goin’ on in the Spanish Bar, where evidently the bold bandits was priming on raw licker and blasphemy for wholesale murder.

I ducked into the back door and was in the saloon before they knowed it, with a gun in each hand. They all whirled away from the bar and glared at me; there was Red, Squint, and Arizona. Hawkins wasn’t there; I heard him bellering out in the street for Curly.

“Don’t move,” I cautioned ’em.

But as if my remark was a fuse to set off a explosion, they all yelled and went for their guns.

I killed Red before he could unleather his irons, and Squint only got in one shot which chipped my ear before I perforated his anatomy in three important places. Arizona missed me with his left-hand gun, but planted a slug in my thigh with his right, before giving up the ghost, hot lead proving harder than even his skull. It was short and deadly as a concentrated cyclone—guns roaring at close range—bullets spatting into flesh—men falling through the smoke. And just as Arizona dropped, Hawkins loomed in the door with Reynolds’ gun in his hand.

He was big as a house anyhow, and he looked even bigger through the curling smoke, with his eyes blazing and his mustaches bristling. He roared like a hurricane through the mesquite, and we fired simultaneous. His bullet lodged in my shoulder, and the last slug in my right-hand gun knocked his pistol out of his hand, along with a finger or so.

He then give a maddened roar and come plunging at me bare-handed. I planted the last three bullets of my other gun in various necessary parts of his carcass as he come, but they just seemed to irritate him. The last shot went into his belly so close the powder burned his shirt. Every other man I ever shot that way imejitately bent double and dropped, but this New Mexican grizzly merely give a enraged beller, jerked the gun outa my hand, fell on me and started beating my brains out with the butt.

He derned near scalped me with that .45 stock. We rolled over and over across the bloodstained floor, bumping over corpses and splintering chairs and tables, him bellering like a bull and choking me with one hand and bashing my head with the gun handle in the other one, and me feeding my bowie to him free and generous in the groin, breast, neck, and belly. I fed it to him sixteen times before he stiffened and went limp. I could hardly believe I’d won. I’d begun to think he couldn’t be croaked. I rize up groggily and shaken some of the blood outa my eyes, and pulled back a loose flap of scalp, and stared dizzily at that shambles—

Presently the awed citizens of Smokeville crept out of their refuges and looked in pallidly to where I sot amidst the ruins, with my bloody head in my hands, weeping bitterly. Old man Garfield was there, and Miss Joan, and Clanton and Reynolds, and a lot of others.

“G-good gosh!” hollored Clanton, wild-eyed. “Are we seein’ things?”

“I reckon you want yore badge,” I says sadly, pulling it off my shirt.

He waved it away with a shaking hand. “You keep it!” he says. “I think Smokeville has found herself a real sheriff at last! Hey, boys?”

“You bet!” they hollered. “Keep the badge and be our regular sheriff!”

“Naw,” I gulped, wiping away some tears. “This ain’t my game. I just mixed in to help some folks. You keep that dough, Miss Joan, and you keep the resternt, Mr. Garfield. It was yore dough by rights. I ain’t no sheriff. I appreshiates yore trust, but if you all would just be so kind as to dig some of this here lead outa me, and sew my scalp back onto my skull in nine or ten places, I’ll be on my way. I got to go to Californy. Pap told me to.”

“But what you cryin’ about?” they asked in awe.

“Aw, I’m just homesick,” I sobbed, glancing around at the blood-smeared ruins. “This here reminds me so much of Knife River, way back in Texas!”