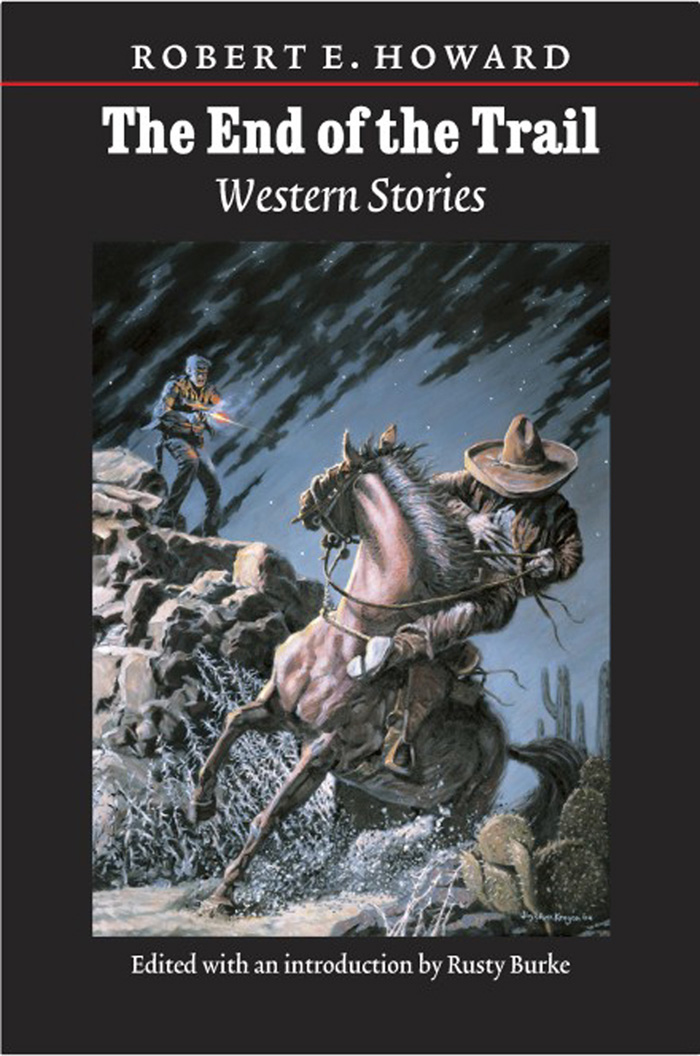

Cover from the collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The Howard Collector, #6 (Spring 1965),

though here taken from the 2005 collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories.

Steve Allison, also known as the Sonora Kid, was standing alone at the Gold Dust Bar when Johnny Elkins entered, glanced furtively at the bartender, and leaned close to Allison’s elbow. Out of the corner of his mouth he muttered: “Steve, they’re out to get you.”

The Kid showed no sign that he had heard. He was a wiry young man, slightly above medium height, slim, but strong as a cougar. His skin was burned dark by the sun and winds of many dim trails, and from under the broad rim of his hat, his eyes glinted grey as chilled steel. Except for those eyes he might have been but one more of the army of cowpunchers that rode up the Chisholm yearly; but low on his hips hung two ivory-butted guns, and the worn leather of their scabbards proclaimed that their presence was no mere matter of display.

The Kid emptied his glass before he answered, softly.

“Who’s out to get me?”

“Grizzly Gullin!” Elkins shot an uneasy glance toward the door as he whispered the formidable name. “The town’s full of buffalo hunters, and they’re on the prod. They ain’t talkin’ much, but I got wind of who they’re stalkin’, and it’s you!”

The Kid rang a coin on the bar, scooped up his change and turned away. Elkins rolled after him, trying to match his friend’s long stride. Elkins was freckled, bow-legged, and of negligible stature. They emerged from the saloon and tramped along the dusty street for some yards before either spoke.

“Dawggone you, Kid,” panted Elkins. “You make me plumb mad. I tell you, somebody in this cowtown is primin’ them shaggy-hided hunters with bad licker and devilishness.”

“Who?”

“How’m I goin’ to know? But that blame’ Mike Connolly ain’t got no love for you, since you took some of the boys away from him that he was goin’ to lock up when we was up here last year. You know he was a buffalo hunter too, once. Them fellows stand in together. They can pot you cold, and he won’t turn a finger.”

“Nobody asks him to turn a finger,” retorted Allison with the quick flash of vanity that characterized the gunfighter. “I don’t need no buffalo-skinnin’ cowtown marshal to shoo a gang of bushy-headed hunters off of me.”

“Le’s ride,” urged Elkins. “What are you waitin’ on? The boys pulled out yesterday.”

“Well,” answered Allison, “you know we brought in the biggest herd that’s come to this town this year. We sold to R. J. Blaine, the new cattle-buyer, and we kind of caught him flatfooted. He didn’t have enough ready cash to pay for the herd in full. He give me enough to pay off the boys, though, and sent to Abilene for more. It may get here today. Yesterday I sent the boys down the trail. They’d blowed in most of their money, and with all these buffalo hunters that’s swarmin’ in to town, I was afraid they’d get into a ruckus. So I told ’em to head south, and I’d wait for the money and catch up with ’em by the time they hit the Arkansas.”

“Old man Donnelly is so blame sot in his ways he’s a plumb pest sometimes,” grumbled Elkins. “Why couldn’t Blaine send him a draft or somethin’?”

“Donnelly don’t trust banks,” answered the Kid. “You know that. He keeps his money in a big safe in the ranch house, and he always wants his trail boss to bring the money for the cows in big bills.”

“Which is plumb nice for the trail boss,” snarled Elkins. “It ain’t enough to haze four thousand mossy horns from the lower Río Grande clean to Kansas; his pore damn’ sucker of a trail boss has got to risk his life totin’ the cash money all the way back. Why, Hell, Steve, at twenty dollars a head, that wad’ll make a roll that’d choke a mule. Every outlaw between here and Laredo will be gunnin’ for yore hide.”

“I’m goin’ to see Blaine now,” answered the Kid abruptly. “But money or not, I ain’t dustin’ out till I’ve had a show-down with Gullin. He can’t say he run me out of town.”

He turned aside into the unpainted board building that served as dwelling place and office for the town’s leading business man.

Blaine greeted him cordially as he entered. The cattle buyer was a big man, well-fed and well-dressed. If not typical, he was a good representation of one of the many types following the steel ribbons westward across the Kansas plains, where, at the magic touch of the steel, new towns blossomed overnight, creating fresh markets for the cattle that rolled up in endless waves from the south. Shrewd, ambitious, and with a better education than most, the man was the dominating factor in this newgrown town, which hoped to rival and eclipse the older cowtowns of Abilene, Newton and Wichita. Blaine had been a gambler in Nevada mining camps before the westward drive of the rails had started the big cattle boom. Though he wore no weapon openly, men said that in his gambling days no faro-dealer in the west was his equal in gun-skill.

“I guess I know what you’re after, Allison,” Blaine laughed. “Well, it’s here. Came in this morning.” Reaching into his ponderous safe he laid a bulky roll of bills on the table. “Count ’em,” he requested. The Kid shook his head.

“I’ll take your word for it.” He drew a black leather bag from his pocket, stuffed the bills into it, and made the draw string fast. The whole made a package of no small bulk.

“You mean to tote all that money down the trail with you?” Blaine demanded.

“Clean to the Tomahawk ranch house,” grinned the Kid. “Old man Donnelly won’t have it no other way.”

“You’re taking a big risk,” said Blaine bluntly. “Why don’t you let me give you a draft for the amount on the First National Bank of Kansas City?”

“The old man don’t do business with no banks,” replied the Kid. “He likes his money where he can lay hands on it all the time.”

“Well, that’s his business and yours,” answered the cattle buyer. “The tally record and the bill of sale we fixed up the other day, but suppose you sign this receipt, just as a matter of form. It shows I’ve paid you the money in due form and proper amount.”

The Kid signed the receipt, and Blaine, as he folded the paper for placing it in safe-keeping, remarked: “I understand your vaqueros pulled out yesterday.”

“Yeah, that’s right.”

“That means you’ll be riding alone part of the way,” protested Blaine. “And with all that money—”

“Aw, I’ll be alright, I reckon,” answered the Kid. Because he was naturally reticent, he did not add that he would be accompanied by Johnny Elkins, a former Tomahawk hand who had remained in Kansas since the drive of the last year, and now, wearied of the northern range, was riding south with his old friend.

“I reckon the trail will be a lot safer than town, maybe,” said Allison; “so I’m goin’ to leave this money with you for safe-keepin’ for awhile. I got some business to ’tend to. I’ll call for it sudden-like, maybe, late tonight, or early in the mornin’. If I don’t call at all—well, I can trust you to see it gets to old man Donnelly eventually.”

As he strode from Blaine’s office, his spurs jingling in the dust, a ragged individual sidled up to him and said: “Grizzly Gullin and the boys want to know if you got guts enough to come down to the Buffalo Hump.”

“Go back and tell ’em I’ll be there,” as softly answered the Kid.

The fellow hurried away in the deepening dusk, and the Kid went swiftly to his hotel, thence to a livery stable. Presently he again came up the street, but this time astride a wiry mustang. The cowtown was awake and going full blast. Tinny pianos blared from dance halls, boot heels stamped on the board walks, saloon doors swung violently, and the yipping of hilarious revelers was punctuated by the shrill laughter of women, and the occasional crack of pistols. The trail riders were celebrating, releasing the nervous energy stored up on that grinding thousand-mile trek.

There was nothing restrained, softened or refined about the scene. All was primitive, wild, raw as the naked boards of the houses that stood up gaunt and unadorned against the prairie stars.

Mike Connolly and his deputies stalked from dance hall to dance hall, glared into every saloon, into every gambling dive. They maintained order at pistol point, and they had no love for the lean bronzed riders who hazed the herds up the trail men called the Chisholm.

There were, indeed, hard characters among these riders. It was a hard life, that bred hard men. At first the trail drivers came seeking only a peaceful market. Fighting their way through hostile lands swarming with Indians and white outlaws, they expected to find rest, safety and the means of enjoyment in the Kansas towns. But the cowtowns soon swarmed with gamblers, crooks, professional killers, parasites that follow every boom, whether of gold, silver, oil or cattle. An unsophisticated cowboy found the dangers of the trail less than the dangers of the boom-towns.

They began to ride up the trails with their guns strapped down, ready for trouble, ready to fight Indians and outlaws on the trail, gamblers and marshals in the towns. Gunfighters, formerly limited mainly to officers and gamblers, began to be found in the ranks of the cowboys. Of this breed was Steve Allison, and it was because of this that old John Donnelly had chosen him for his trail boss.

The Kid tied his horse to the hitching rack by the Buffalo Hump, and strode lightly toward the square of golden light that marked the doorway. Inside glasses crashed, oaths and boisterous laughter crackled, and a voice roared:

It wuz on a starry night, in the month of July,

They robbed the Danville train;

It wuz two of the Younger boys what opened the safe,

And toted the gold away!

A shadowy form bulked up before the Kid, and even as his right hand gun slid silently from its scabbard, Johnny Elkins’ voice hissed: “Steve, are you locoed?”

Johnny’s fingers gripped the Kid’s arm, and Allison felt the youngster trembling in his excitement. His face was a pale blur in the dim light.

“Don’t go in there, Steve!” his voice thrummed with urgency.

“Who-all’s in there?” asked the Kid softly.

“Every damn’ buff-hunter in town! Grizzly Gullin’s been ravin’ and swearin’ he’ll cut out yore heart and eat it raw. I tell you, Steve, they know it ’uz you that killed Bill Galt, and they craves yore scalp.”

“Well, they can have it if they got the guts to take it,” said the Kid without passion.

“But you know their way,” protested Johnny. “If you go in there and get into a fight with Gullin they’ll shoot you in the back. Somebody’ll shoot out the light, and in the scramble nobody’ll know who done it—or give a damn.”

“I know.” None knew the tricks of the cowtown ruffians better than the Kid. “That’s the way some of these tinhorns got Joe Ord, trail boss for the Triple L, last month. Robbed him, too, I reckon. Leastways, he’d been paid for the cows he brung up the trail, and they never found the money. But that was gamblers, not hunters.”

“What’s the difference?”

“None, as far as stoppin’ a bullet goes,” grinned the Kid. “But listen here, Johnny—” His voice sank lower, and Elkins listened intently. He shook his head and swore dubiously, but when the Kid turned and strode toward the lamp-lit doorway, the bowlegged puncher rolled after him.

As the Kid framed himself in the door, the clamor within ceased suddenly. The fellow who had been singing, or rather bellowing, broke short his lament for Jesse James, and wheeled like a great bear toward the doorway.

Allison’s quick gaze swept over the saloon. It was thronged with buffalo hunters, to which the establishment catered. Besides the bartenders, there was but one man there not a hunter—the marshal, Mike Connolly, a broad built man, with a hard immobile face, and a heavy gun strapped low on either hip.

The hunters were all big men, many of them clad in buckskin and Indian moccasins. All were burned dark as Indians, and they wore their hair long. Living an incredibly primitive life, they were hard and ferocious as red savages, and infinitely more dangerous. Hairy, burly, fierce, their eyes gleamed in the lamp light, their hands hovered near the great butcher knives in their belts.

In the midst of the room stood one who loomed above the rest—a great, shaggy brute who looked more like a bear than a man: Grizzly Gullin. This man gave a roar as Allison entered, and rolled toward him, small eyes blazing, thick hairy hands working as if to tear out his enemy’s throat.

“What you doin’ here, Allison?” His voice filled the saloon, and almost seemed to make the one kerosene lamp flicker.

“Heard you all craved to meet me, Gullin,” the Kid answered tranquilly. His eyes never exactly left Gullin’s hairy face, but they darted sidelong glances that took in all the room.

Gullin rumbled like an enraged bull. His shaggy head wagged from side to side, his hairy hands moved back and forth, without actually reaching toward a weapon. Like most of the other hunters he wore a gun, but it was with the long broad-bladed butcher knife strapped high on his left side, hilt forward, that he was deadly.

“You killed Bill Galt!” he roared, and the crowd behind him rumbled menacingly.

“Yeah, I did,” admitted the Kid.

Gullin’s face grew black; his veins swelled; he teetered forward on his moccasined feet as if about to hurl himself bodily at his enemy.

“You admit it!” he yelled. “You killed him in cold blood—”

“I shot him in a fair fight,” snarled the Kid, his eyes suddenly icy. “Last year he stampeded a herd of Tomahawk cattle just out of pure cussedness—run a herd of buffalo into ’em. They went over a bluff by the hundreds, and took one of the hands with ’em. He was smashed to a pulp. When we come up the trail this year, I met Bill Galt on the Canadian, and I blew his light out. But he had an even break.”

“You’re a liar!” bellowed Gullin. “You shot him in the back. A man heard you braggin’ about it, and told us. You murdered Bill and let him lay there like he was a dog.”

“I wouldn’t have let a dog lay,” answered the Kid with bitter scorn. “When I rode off Galt was buzzard meat and I didn’t feel no call to cover him up. But I didn’t shoot him in the back.”

“You can’t lie out of it!” howled Gullin, brandishing his huge fists.

The Kid cast a quick look at the hemming faces, dark with passion, the straining bodies. It was something more than the old feud of cowpuncher and buffalo-hunter. Mike Connolly stood back, aloof, silent.

“Well, why don’t you start the ball rollin’?” demanded the Kid, half crouching, hands hovering above his gun butts.

“ ’Cause we ain’t murderers like you,” sneered Gullin. “Connolly there is goin’ to see fair play. You’re a gunman; you got guts enough to fight with a man’s weepons?”

“Meanin’ a butcher knife? Gullin, there ain’t no weapon I’m afraid to meet you with!”

“Alright!” yelled the hunter, tearing off his gun belt and tossing it to Mike Connolly. “You ain’t wearin’ no knife; git him one, Joe.”

The bartender ducked down into an assortment of lethal weapons pawned to him at various times, in return for drinks, by impecunious customers, and laid half a dozen knives on the plank bar.

The Kid, drawing both his guns, handed them to Johnny Elkins, who casually backed toward the door. Allison, after a brief inspection, took up a knife with a heavy hilt and a narrow, comparatively short blade—a weapon of unmistakable Spanish make.

The hunters had drawn back around the walls, leaving a space clear. The Kid had no illusions about what was to follow. He knew his own reputation; knew that the whole affair was a trap, planned to get his deadly guns out of his hands. If Gullin’s knife failed, it would be a bullet in the cowboy’s back. The Kid stamped in the sawdust as if trying the footing, moving near an open window as he did so. Then he turned and indicated that he was ready.

Gullin ripped out his knife and charged like the bear for which he was named. For all his bulk he was quick as a cat. His moccasin-shod feet were adapted to the work at hand. Opposing was the Kid, much inferior in bulk, wearing high-heeled boots unfitted for quick work on the sawdust-strewn floor. The knife in his hand looked small compared to the great scimitar-curved blade of Gullin. What the hunters overlooked, or did not know, was that Allison was raised in a land swarming with Mexican knife-fighters.

The Kid, facing that roaring, hurtling bulk, knew that if they came to hand-grips, he was lost. He had seen Gullin, his shoulder broken by a cowboy’s bullet, leap like a huge cat through the air and drive the knife, with his left hand, through his enemy’s heart.

Gullin roared and charged; the Kid’s hand went back and snapped out. The Spanish knife flashed through the lamp-light like a beam of blue lightning, and thudded against Gullin’s breast—the hilt quivered under his heart. The giant stopped short, staggered. His mouth gaped and blood gushed from it. He pitched headlong—

As Gullin fell, the Kid’s hand whipped inside his shirt and out again, gripping a double-barreled derringer. Even as it caught the lamp light, it cracked twice. A hunter lifting a cocked sixshooter crumpled, and the lamp shattered, casting a shower of blazing oil.

In the darkness bedlam broke loose. There were wild shots, stampeding of feet, splintering of chairs and tables, curses, yells, and Mike Connolly’s stentorian voice demanding a light.

The Kid had wheeled, even as the room was plunged in darkness, and dived headlong through the nearby window. He hit on his feet, catlike, and raced toward the hitching rack. A form loomed up before him, and even as he instinctively menaced it with the empty derringer, he recognized it.

“Johnny! Got my guns?”

Two familiar smooth butts were shoved into his eager hands.

“I beat it as soon as everybody was watchin’ you all,” Johnny spluttered with excitement. “You nailed him, Steve? By the good golly—”

“Get your cayuse and hit the trail, Johnny,” ordered Allison, swinging up on his horse. “Dust it out of town and wait for me at that creek crossin’ three miles south of town. I’m goin’ after the money Blaine’s holdin’ for me. Vamoose!”

A few minutes later the Kid dropped reins over his horse’s head and slid up to the lighted window inside which he saw Richard J. Blaine busily engaged in writing. At the Kid’s hiss he looked up, gaped, and started violently. The Kid pushed the partly open window up the rest of the way, and climbed in.

“I ain’t hardly got no time to go around to the door,” he apologized. “If you’ll give me the money. I’ll be makin’ tracks.”

Blaine rose, still confused, hastily crumpling up the sheet on which he had been writing, and thrusting it into his pocket. He turned toward his safe, which stood open, and inside which Allison could see the black leather bag, then turned back, as if struck by a sudden thought.

“Any trouble?”

“No trouble; just a bunch of fool buffalo hunters.”

“Oh!” The cattle buyer seemed to be regaining some of his composure. The color came back to his face.

“You startled the devil out of me, coming through that window. What about those hunters?”

“They took it ill because I killed that stampedin’ side-winder Bill Galt,” answered the Kid. “I don’t know how they found out. I ain’t told nobody in this town except you and Johnny Elkins. Reckon some of my outfit must have talked. Not that I give a damn. But I don’t go around braggin’ about the coyotes I have to shoot. They sure planned to get me cold—” in a few words he related what happened at the Buffalo Hump. “Now I reckon they’ll try lynch-law,” he concluded. “They’ll swear I murdered somebody.”

“Oh, I guess not,” laughed Blaine. “Bed down here till mornin’.”

“Not a chance; I’m dustin’ now.”

“Well, have a drink before you go,” urged Blaine.

“I ain’t hardly got time.” The Kid was listening for sounds of pursuit. It was quite possible the maddened hunters might trail him. And he knew that Mike Connolly would give him no protection against the mob.

“Oh, a few minutes won’t make any difference,” laughed Blaine. “Wait, I’ll get the liquor.”

Frontier courtesy precluded a refusal. Blaine passed into an adjoining room, and the Kid heard him fumbling about. The Kid stood in the center of the office-room, nervous, alert, and because it was his nature to observe everything, he noticed a ball of paper crumpled on the floor, inkstained—evidently part of a letter Blaine had spoiled and discarded. He would have paid no attention to it, but suddenly he saw his own name scrawled upon it.

Quickly he bent and secured it. Smoothing out the crumpled sheet, he read. It was a letter addressed to John Donnelly, and it said: “Your trail boss Allison was killed in a barroom brawl. I had paid him for the cows, and have a receipt, signed by him. However, the money was not found on his body. Marshal Connolly verifies that fact. He had been gambling heavily, I understand, and he must have used your money after he ran out of his own. It’s too bad, but—”

The door opened and Blaine stood framed in it, whiskey bottle and glasses in hand. He saw the paper in the Kid’s fingers, and he went livid.

The bottle and glasses fell to the floor with a shattering crash. Blaine’s hand darted under his coat and out, just as the Texan’s .45 cleared leather. The shots crashed like a double reverberation—but it was the .45 that thundered first. The window behind Allison shattered, and Blaine tumbled to the floor, to lie in a widening pool of dark crimson.

The Kid snatched the bulky black leather pouch from the opened safe, and stuffed it into his shirt as he ran from the room. He forked his mustang and headed south at a run. Behind him sounded the mingled clamor of cowtown night life, mixed now with an increasing, ominous roar—the bellow of the manhunt. The Kid grinned hardly—knife, bullet, noose—all had failed that night; as well as the sinister plotting of the last man in Kansas Allison would have dreamed of suspecting.

Johnny Elkins was waiting for him at the appointed place, and together they took the trail that ran southward for a thousand miles.

“Well?” Johnny wriggled impatiently. Allison explained in a few words.

“I see it all now. Blaine figgered on gettin’ cows and money too. He held up the pay for the herd, so as to get me in town alone, so he thought. He worked them hunters up to get me. He had the receipt to prove that he’d paid me the dough. Then if I got killed, and the money not on me— Right at the last he tried to keep me there, till the mob found me, I reckon.”

“But he couldn’t know you’d leave the dough with him for safekeepin’,” objected Johnny.

“Well, it was a natural thing to do. And if I hadn’t, I reckon Connolly would have took it off me, after I was killed in the Buffalo Hump. He was Blaine’s man. That must have been how and why Joe Ord got his.”

“And everybody figgered Blaine was such a big man,” meditated Johnny.

“Well,” answered Allison, “a few more big herds grabbed for nothin’, and I reckon he would have been a big man; but big or little, it’s all the same to a .45.”

Which comment embraced the full philosophy of the gunfighter.