Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

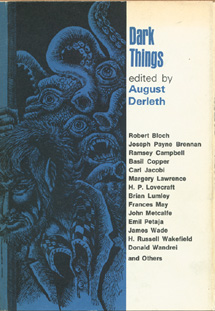

Version completed by August Derleth: Published in Dark Things, 1971.

(Original fragment published in The Howard Reader #8, 2003.)

First is Howard’s original fragment; then Derleth’s “completed” version, which is divided into three chapters as follows:

| I. | II. | III. |

“And so you see,” said my friend James Conrad, his pale, keen face alight, “why I am studying the strange case of Justin Geoffrey—seeking to find, either in his own life, or in his family line, the reason for his divergence from the family type. I am trying to discover just what made Justin the man he was.”

“Have you met with success?” I asked. “I see you have procured not only his personal history but his family tree. Surely, with your deep knowledge of biology and psychology, you can explain this strange poet, Geoffrey.”

Conrad shook his head, a baffled look in his scintillant eyes. “I admit I cannot understand it. To the average man, there would appear to be no mystery—Justin Geoffrey was simply a freak, half genius, half maniac. He would say that he ‘just happened’ in the same manner in which he would attempt to explain the crooked growth of a tree. But twisted minds are no more causeless than twisted trees. There is always a reason—and save for one seemingly trivial incident I can find no reason for Justin’s life, as he lived it.

“He was a poet. Trace the lineage of any rhymer you wish, and you will find poets or musicians among his ancestors. But I have studied his family tree back for five hundred years and find neither poet nor singer, nor any thing that might suggest there had ever been one in the Geoffrey family. They are people of good blood, but of the most staid and prosaic type you could find. Originally an old English family of the country squire class, who became impoverished and came to America to rebuild their fortunes, they settled in New York in 1690 and though their descendants have scattered over the country, all—save Justin alone—have remained much of a type—sober, industrious merchants. Both of his parents are of this class, and likewise his brothers and sisters. His brother John is a successful banker in Cincinnati. Eustace is the junior partner of a law firm in New York, and William, the younger brother, is in his junior year in Harvard, already showing the ear-marks of a successful bond salesman. Of the three sisters of Justin, one is married to the dullest business man imaginable, one is a teacher in a grade school and the other graduates from Vassar this year. Not one of them shows the slightest sign of the characteristics which marked Justin. He was like a stranger, an alien among them. They are all known as kindly, honest people. Granted; but I found them intolerably dull and apparently entirely without imagination. Yet Justin, a man of their own blood and flesh, dwelt in a world of his own making, a world so fantastic and utterly bizarre that it was quite outside and beyond my own gropings—and I have never been accused of a lack of imagination.

“Justin Geoffrey died raving in a madhouse, just as he himself had often predicted. This was enough to explain his mental wanderings to the average man; to me it is only the beginning of the question. What drove Justin Geoffrey mad? Insanity is either acquired or inherited. In his case it was certainly not inherited. I have proved that to my own satisfaction. As far back as the records go, no man, woman or child in the Geoffrey family has ever showed the slightest taint of a diseased mind. Justin, then, acquired his lunacy. But how? No disease made him what he was; he was unusually healthy, like all his family. His people said he had never been sick a day in his life. There were no abnormalities present at birth. Now comes the strange part. Up to the age of ten he was no whit different from his brothers. When he was ten, the change came over him.

“He began to be tortured by wild and fearful dreams which occurred almost nightly and which continued until the day of his death. As we know, instead of fading as most dreams of childhood do, these dreams increased in vividness and terror, until they shadowed his whole life. Toward the last, they merged so terribly with his waking thoughts that they seemed grisly realities and his dying shrieks and blasphemies shocked even the hardened keepers of the madhouse.

“Coincidental with these dreams came a drawing away from his companions and his own family. From a completely extrovert, gregarious little animal he became almost a recluse. He wandered by himself more than is good for a child and he preferred to do his roaming at night. Mrs. Geoffrey has told how time and again she would come into the room where he and his brother Eustace slept, after they had gone to bed, to find Eustace sleeping peacefully, but the open window telling her of Justin’s departure. The lad would be out under the stars, pushing his way through the silent willows along some sleeping river, or wading through the dew-wet grass, or rousing the drowsy cattle in some quiet meadow by his passing.

“This is a stanza of a poem Justin wrote at the age of eleven.” Conrad took up a volume published by a very exclusive house and read:

Behind the Veil, what gulfs of Time and Space?

What blinking, mowing things to blast the sight?

I shrink before a vague, colossal Face

Born in the mad immensities of Night.

“What!” I exclaimed. “Do you mean to tell me that a boy of eleven wrote those lines?”

“I most certainly do! His poetry at that age was crude and groping, but it showed even then sure promise of the mad genius that was later to blaze forth from his pen. In another family, he had certainly been encouraged and had blossomed forth as an infant prodigy. But his unspeakably prosaic family saw in his scribbling only a waste of time and an abnormality which they thought they must nip in the bud. Bah! Dam up the abhorrent black rivers that run blindly through the African jungles! But they did prevent him giving his unusual talents full swing for a space, and it was not until he was seventeen that his poems were first given to the world, by the aid of a friend who discovered him struggling and starving in Greenwich Village, whither he had fled from the stifling environments of his home.

“But the abnormalities which his family thought they saw in his poetry were not those which I see. To them, anyone who does not make his living by selling potatoes is abnormal. They sought to discipline his poetic leanings out of him, and his brother John bears a scar to this day, a memento of the day he sought in a big-brotherly way to chastise his younger brother for neglecting some work for his scribbling. Justin’s temper was sudden and terrible; his whole disposition was as different from his stolid, good-natured people as a tiger differs from oxen. Nor does he favor them, save in a vague way about the features. They are round-faced, stocky, inclined to portliness. He was thin almost to emaciation, with a narrow-bridged nose and a face like a hawk’s. His eyes blazed with an inner passion and his tousled black hair fell over a brow strangely narrow. That forehead of his was one of his unpleasant features. I cannot say why, but I never glanced at that pale, high, narrow forehead that I did not unconsciously suppress a shudder!

“And as I said, all this change came after he was ten. I have seen a picture taken of him and his brothers when he was nine, and I had some difficulty in picking him out from them. He had the same stubby build, the same round, dull, good-natured face. One would think a changeling had been substituted for Justin Geoffrey at the age of ten!”

I shook my head in puzzlement and Conrad continued.

“All the children except Justin went through high school and entered college. Justin finished high school much against his will. He differed from his brothers and sisters in this as in all other things. They worked industriously in school but outside they seldom opened a book. Justin was a tireless searcher for knowledge, but it was knowledge of his own choosing. He despised and detested the courses of education given in school and repeatedly condemned the triviality and uselessness of such education.

“He refused point blank to go to college. At the time of his death at the age of twenty-one, he was curiously unbalanced. In many ways he was abysmally ignorant. For instance he knew nothing whatever of the higher mathematics and he swore that of all knowledge this was the most useless, for, far from being the one solid fact in the universe, he contended that mathematics were the most unstable and unsure. He knew nothing of sociology, economics, philosophy or science. He never kept himself posted on current events and he knew no more of modern history than he had learned in school. But he did know ancient history, and he had a great store of ancient magic, Kirowan.

“He was interested in ancient languages and was perversely stubborn in his use of obsolete words and archaic phrases. Now how, Kirowan, did this comparatively uncultured youth, with no background of literary heredity behind him, manage to create such horrific images as he did?”

“Why,” said I, “poets feel—they write from instinct rather than knowledge. A great poet may be a very ignorant man in other ways, and have no real concrete knowledge on his own poetic subjects. Poetry is a weave of shadows—impressions cast on the consciousness which cannot be described otherwise.”

“Exactly!” Conrad snapped. “And whence came these impressions to Justin Geoffrey? Well, to continue, the change in Justin began when he was ten years old. His dreams seem to date from a night he spent near an old deserted farm house. His family were visiting some friends who lived in a small village in New York State—up close to the foot of the Catskills. Justin, I gather, went fishing with some other boys, strayed away from them, got lost and was found by the searchers next morning slumbering peacefully in the grove which surrounds the house. With the characteristic stolidity of the Geoffreys, he had been unshaken by an experience which would have driven many a small boy into hysteria. He merely said that he had wandered over the countryside until he came to this house and being unable to get in, had slept among the trees, it being late in the summer. Nothing had frightened him, but he said that he had had strange and extraordinary dreams which he could not describe but which had seemed strangely vivid at the time. This alone was unusual—the Geoffreys were no more troubled with nightmares than a hog is.

“But Justin continued to dream wildly and strangely and as I said, to change in thoughts, ideas and demeanor. Evidently, then, it was that incident which made him what he was. I wrote to the mayor of the village asking him if there was any legend connected with the house but his reply, while arousing my interest, told me nothing. He merely said that the house had been there ever since anyone could remember, but had been unoccupied for at least fifty years. He said the ownership was in some dispute, and he added that, strange to say, the place had always been known merely as The House by the people of Old Dutchtown. He said that so far as he knew, no unsavory tales were connected with it, and he sent me a Kodak snapshot of it.”

Here Conrad produced a small print and held it up for me to see. I sprang up, almost startled.

“That? Why, Conrad, I’ve seen that same landscape before—those tall sombre oaks, with the castle-like house half concealed among them—I’ve got it! It’s a painting by Humphrey Skuyler, hanging in the art gallery of the Harlequin Club.”

“Indeed!” Conrad’s eyes lighted up. “Why, both of us know Skuyler well. Let’s go up to his studio and ask him what he knows about The House, if anything.”

We found the artist hard at work as usual, on a bizarre subject. As he was fortunate in being of a very wealthy family, he was able to paint for his own enjoyment—and his tastes ran to the weird and outre. He was not a man who affected unusual dress and manners, but he looked the temperamental artist. He was about my height, some five feet and ten inches, but he was slim as a girl with long white nervous fingers, a knife-edge face and a shock of unruly hair tumbling over a high pale forehead.

“The House, yes, yes,” he said in his quick, jerky manner, “I painted it. I was looking on a map one day and the name Old Dutchtown intrigued me. I went up there hoping for some subjects, but I found nothing in the town. I did find that old house several miles out.”

“I wondered, when I saw the painting,” I said, “why you merely painted a deserted house without the usual accompaniment of ghastly faces peering out of the upstairs windows or misshapen shapes roosting on the gables.”

“No?” he snapped. “And didn’t anything about the mere picture impress you?”

“Yes, it did,” I admitted. “It made me shudder.”

“Exactly!” he cried. “To have elaborated the painting with figures from my own paltry brain would have spoiled the effect. The effect of horror is most gained when the sensation is most intangible. To put the horror into a visible shape, no matter how gibbous or mistily, is to lessen the effect. I paint an ordinary tumble-down farmhouse with the hint of a ghastly face at a window; but this house—this House—needs no such mummery or charlatanry. It fairly exudes an aura of abnormality—that is, to a man sensitive to such impressions.”

Conrad nodded. “I received that impression from the snapshot. The trees obscure much of the building but the architecture seems very unfamiliar to me.”

“I should say so. I’m not altogether unversed in the history of architecture and I was unable to classify it. The natives say it was built by the Dutch who first settled that part of the country but the style is no more Dutch than it’s Greek. There’s something almost Oriental about the thing, and yet it’s not that either. At any rate, it’s old—that cannot be denied.”

“Did you go in The House?”

“I did not. The doors and windows were locked and I had no desire to commit burglary. It hasn’t been long since I was prosecuted by a crabbed old farmer in Vermont for forcing my way into an old deserted house of his in order to paint the interior.”

“Will you go with me to Old Dutchtown?” asked Conrad suddenly.

Skuyler smiled. “I see your interest is aroused—yes, if you think you can get us into The House without having us dragged up in court afterwards. I have an eccentric reputation enough as it is; a few more suits like the one I mentioned and I’ll be looked on as a complete lunatic. And what about you, Kirowan?”

“Of course I’ll go,” I answered.

“I was sure of that,” said Conrad. “I don’t even bother to ask him to accompany me on my weird explorations any more—I know he’s eager as I.”

And so we came to Old Dutchtown on a warm late summer morning.

“Drowsy and dull with age the houses blink,

On aimless streets that youthfulness forget—

But what time-grisly figures glide and slink

Down the old alleys when the moon has set?”

Thus Conrad quoted the phantasies of Justin Geoffrey as we looked down on the slumbering village of Old Dutchtown from the hill over which the road passed before descending into the crooked dusty streets.

“Do you suppose he had this town in mind when he wrote that?”

“It fits the description, doesn’t it—‘High gables of an earlier, ruder age’—look—there are your Dutch houses and old Colonial buildings—I can see why you were attracted by this town, Skuyler, it breathes a very musk of antiquity. Some of those houses are three hundred years old. And what an atmosphere of decadence hovers over the whole town.”

We were met by the mayor of the place, a man whose up-to-the-minute clothes and manners contrasted strangely with the sleepiness of the town and the slow, easy-going ways of most of the natives. He remembered Skuyler’s visit there—indeed, the coming of any stranger into this little backwash town was an event to be remembered by the inhabitants. It seemed strange to think that within a hundred or so miles there roared and throbbed the greatest metropolis of the world.

Conrad could not wait a moment, so the mayor accompanied us to The House. The first glance of it sent a shudder of repulsion through me. It stood in the midst of a sort of upland, between two fertile farms, the stone fences of which ran to within a hundred or so yards on either side. A ring of tall, gnarled oaks entirely surrounded the house, which glimmered through their branches like a bare and time-battered skull.

“Who owns this land?” the artist asked.

“Why, the title is in some dispute,” answered the mayor. “Jediah Alders owns that farm there, and Squire Abner owns the other. Abner claims The House is part of the Alders farm, and Jediah is just as loud in his assertions that the Squire’s grandfather bought it from the Dutch family who first owned it.”

“That sounds backwards,” commented Conrad. “Each one denies ownership.”

“That’s not so strange,” said Skuyler. “Would you want a place like that to be part of your estate?”

“No,” said Conrad after a moment’s silent contemplation, “I would not.”

“Between ourselves,” broke in the mayor, “neither of the farmers want to pay the taxes on the property as the land about it is absolutely useless. The barrenness of the soil extends for some little distance in all directions and the seed planted close to those stone fences on both farms yields little. These oak trees seem to sap the very life of the soil.”

“Why have the trees not been cut down?” asked Conrad. “I have never encountered any sentiment among the farmers of this state.”

“Why, as the ownership has been in dispute for the past fifty years, no one has liked to take it on himself. And then the trees are so old and of such sturdy growth it would entail a great deal of labor. And there is a foolish superstition attached to that grove—a long time ago a man was badly cut by his own axe, trying to chop down one of the trees—an accident that might occur anywhere—and the villagers attached over-much importance to the incident.”

“Well,” said Conrad, “if the land about The House is useless, why not rent the building itself, or sell it?”

For the first time the mayor looked embarrassed.

“Why, none of the villagers would rent or buy it, as no good land goes with it, and to tell you the truth, it has been found impossible to enter The House!”

“Impossible?”

“Well,” he amended, “the doors and windows are heavily barred and bolted, and either the keys are in possession of someone who does not care to divulge the secret, or else they have been lost. I have thought that possibly someone was using The House for a bootleg den and had a reason for keeping the curious out but no light has ever been seen there, and no one is ever seen slinking about the place.”

We had passed through the circling ring of sullen oaks and stood before the building.

“And so you see,” said my friend James Conrad, his pale, keen face alight, “why I am studying the strange case of Justin Geoffrey—seeking to find, either in his own life, or in his family line, the reason for his divergence from the family type. I’m trying to discover just what made Justin the man he was.”

“Have you met with success?” I asked. “I see you have got hold of not only his personal history but his family tree. Surely, with your deep knowledge of biology and psychology, you can explain this strange poet, Geoffrey.”

Conrad shook his head, a baffled look in his scintillant eyes. “I admit I cannot understand it. To the average man, there would appear to be no mystery—Justin Geoffrey was simply a freak, half genius, half maniac. He would say that he ‘just happened’ in the same manner in which he would attempt to explain the crooked growth of a tree. But twisted minds are no more causeless than twisted trees. There is always a reason—and save for one seemingly trivial incident I can find no reason for Justin’s life, as he lived it.

“He was a poet. Trace the lineage of any rhymer you wish, and you’ll find poets or musicians among his ancestors. But I’ve studied his family tree back for five hundred years and find neither poet nor singer, nor anything that might suggest there had ever been one in the Geoffrey family. They are people of good blood, but of the most staid and prosaic type you could find. Originally an old English family of the country squire class, who became impoverished and came to America to rebuild their fortunes, they settled in New York, in 1690 and though their descendants have scattered over the country, all—save Justin alone—have remained much of a type—sober, industrious merchants. Both of his parents are of this class, and likewise his brothers and sisters. His brother John is a successful banker in Cincinnati. Eustace is the junior partner of a law firm in New York, and William, the younger brother, is in his junior year in Harvard, already showing the earmarks of a successful bond salesman. Of the three sisters, one is married to the dullest businessman imaginable, one is a teacher in a grade school and the other graduates from Vassar this year. Not one of them shows the slightest sign of the characteristics which marked Justin. He was like an alien among them. They are all known as kindly, honest people. Granted; but I found them intolerably dull and apparently entirely without imagination. Yet Justin, a man of their own blood and flesh, dwelt in a world of his own making, a world so fantastic and utterly bizarre that it was quite outside and beyond my own gropings—and I’ve never been accused of a lack of imagination.

“Justin Geoffrey died raving in a mad-house, just as he himself had often predicted. This was enough to explain his mental wanderings to the average man; to me it is only the beginning of the question. What drove Justin Geoffrey mad? Insanity is either acquired or inherited. In his case it was certainly not inherited. I have proved that to my own satisfaction. As far back as the records go, no man, woman or child in the Geoffrey family has ever shown the slightest taint of a diseased mind. Justin then, acquired his lunacy. But how? No disease made him what he was; he was unusually healthy, like all his family. His people said he had never been sick a day in his life. There were no abnormalities present at birth. Now comes the strange part. Up to the age of ten he was no whit different from his brothers. When he was ten, the change came over him.

“He began to be tortured by wild and fearful dreams which occurred almost nightly and which continued until the day of his death. As we know, instead of fading as most dreams of childhood do, these dreams increased in vividness and terror, until they shadowed his whole life. Toward the last, they merged so terribly with his waking thoughts that they seemed grisly realities and his dying shrieks and blasphemies shocked even the hardened keepers of the madhouse.

“Coincidental with these dreams came a drawing away from his companions and his own family. From a complete extroverted, gregarious little animal he became almost a recluse. He wandered by himself more than is good for a child and he preferred to do his roaming at night. Mrs. Geoffrey has told how time and again she would come into the room where he and his brother Eustace slept, after they had gone to bed, to find Eustace sleeping peacefully, but the open window telling her of Justin’s departure. The lad would be out under the stars, pushing his way through the silent willows along some sleeping river, or wading through the dew-wet grass, or rousing the drowsy cattle in some quiet meadow by his passing.

“This is a stanza of a poem Justin wrote at the age of eleven.” Conrad took up a volume published by a very exclusive house and read:

“Behind the Veil, what gulfs of Time and Space?

What blinking, mowing things to blast the sight?

I shrink before a vague, colossal Face

Born in the mad immensities of Night.”

“What!” I exclaimed. “Do you mean to tell me that a boy of eleven wrote those lines?”

“I most certainly do! His poetry at that age was crude and groping, but it showed even then sure promise of the mad genius that was later to blaze forth from his pen. In another family he would certainly have been encouraged and would have blossomed forth as an infant prodigy. But his unspeakably prosaic family saw in his scribbling only a waste of time and an abnormality which they thought they must nip in the bud. Bah! Dam up the abhorrent black rivers that run blindly through the African jungles! But they did prevent him giving his unusual talents full swing for a space, and it was not until he was seventeen that his poems were first given to the world, by the aid of a friend who discovered him struggling and starving in Greenwich Village, whither he had fled from the stifling environments of his home.

“But the abnormalities which his family thought they saw in his poetry were not those which I see. To them, anyone who does not make his living by selling potatoes is abnormal. They sought to discipline his poetic leanings out of him, and his brother John bears a scar to this day, a memento of the day he sought in a big brotherly way to chastise his younger brother for neglecting some work for his scribbling. Justin’s temper was sudden and terrible; his whole disposition was as different from his stolid, good-natured people as a tiger differs from oxen. Nor did he favor them, save in a vague way about the features. They are round-faced, stocky, inclined to portliness. He was thin almost to emaciation, with a narrow-bridged nose and a face like a hawk’s. His eyes blazed with an inner passion and his touseled black hair fell over a brow strangely narrow. That forehead of his was one of his unpleasant features. I cannot say why, but I never glanced at that pale, high, narrow forehead that I did not unconsciously suppress a shudder!

“And as I said, all this change came after he was ten. I have seen a picture taken of him and his brothers when he was nine, and I had some difficulty in picking him out from them. He had the same stubby build, the same round, dull, good-natured face. One would think a changling had been substituted for Justin Geoffrey at the age of ten!”

I shook my head in puzzlement and Conrad continued.

“All the children except Justin went through high school and entered college. Justin finished high school much against his will. He differed from his brothers and sisters in this as in all other things. They worked industriously in school but outside they seldom opened a book. Justin was a tireless searcher for knowledge, but it was knowledge of his own choosing. He despised and detested the courses of education given in school and repeatedly condemned the triviality and uselessness of such education.

“He refused point-blank to go to college. At the time of his death at the age of twenty-one, he was curiously unbalanced. In many ways he was abysmally ignorant. For instance, he knew nothing whatever of the higher mathematics and he swore that of all knowledge this was the most useless, for, far from being the one solid fact in the universe, he contended that mathematics were the most unstable and unsure. He knew nothing of sociology, economics, philosophy or science. He never kept himself posted on current events and he knew no more of modern history than he had learned in school. But he did know ancient history and he had a great store of ancient magic, Kirowan.

“He was interested in ancient languages and was perversely stubborn in his use of obsolete words and archaic phrases. Now how, Kirowan, did this comparatively uncultured youth, with no background of literary heredity behind him, manage to create such horrific images as he did?”

“Why,” said I, “poets feel—they write from intuition rather than knowledge. A great poet may be a very ignorant man in other ways, and have no real concrete knowledge on his own poetic subjects. Poetry is a weave of shadows—impressions cast on the consciousness which cannot be described otherwise.”

“Exactly!” Conrad snapped. “And whence came these impressions to Justin Geoffrey? Well, to continue, the change in Justin began when he was ten years old. His dreams seem to date from a night he spent near an old deserted farmhouse. His family were visiting some friends who lived in a small village in New York State—up close to the foot of the Catskills. Justin, I gather, went fishing with some other boys, strayed away from them, got lost and was found by the searchers next morning slumbering peacefully in the grove which surrounds the house. With the characteristic stolidity of the Geoffreys, he had been unshaken by an experience which would have driven many a small boy into hysteria. He merely said that he had wandered over the countryside until he came to this house and being unable to get in, had slept among the trees, it being late in the summer. Nothing had frightened him, but he said that he had had strange and extraordinary dreams which he could not describe but which had seemed strangely vivid at the time. This alone was unusual—the Geoffreys were no more troubled with nightmares than a hog is.

“But Justin continued to dream wildly and strangely and, as I said, to change in thoughts, ideas and demeanor. Evidently then, it was that incident which made him what he was. I wrote to the mayor of the village asking him if there was any legend connected with the house but his reply, while arousing my interest, told me nothing. He merely said that the house had been there ever since anyone could remember, but had been unoccupied for at least fifty years. He said the ownership was in some dispute. He said that as far as he knew, no unsavory tales were connected with it, and he sent me a snapshot of it.”

Here Conrad produced a small print and held it up for me to see. I sprang up, almost startled.

“That? Why, Jim, I’ve seen that same landscape before—those tall sombre oaks, with the castle-like house half concealed among them—I’ve got it! It’s a painting by Humphrey Skuyler, hanging in the art gallery of the Harlequin Club.”

“Indeed!” Conrad’s eyes lighted up. “Why, both of us know Skuyler well. Let’s go up to his studio and ask him what he knows about the house, if anything.”

We found the artist hard at work, as usual, on a bizarre subject. As he was fortunate in being of a very wealthy family, he was able to paint for his own enjoyment—and his tastes ran to the weird and outre. He was not a man who affected unusual dress and manners, but he looked the temperamental artist. He was about my height, some five feet and ten inches, but he was slim as a girl, with long white nervous fingers, a knife-edge face and a shock of unruly hair tumbling over a high pale forehead.

“The house, yes,” he said in his quick, jerky manner, “I painted it. I was looking on a map one day and the name Old Dutchtown intrigued me. I went up there hoping for some subjects, but I found nothing in the town. I did find that old house several miles out.”

“I wondered, when I saw the painting,” I said, “why you merely painted a deserted house without the usual accompaniment of ghastly faces peering out of the upstairs windows or misshapen shapes roosting on the gables.”

“No?” he snapped. “And didn’t anything about the mere picture impress you?”

“Yes, it did,” I admitted. “It made me shudder.”

“Exactly!” he cried. “To have elaborated the painting with figures from my own paltry brain would have spoiled the effect. The effect of horror is best gained when the sensation is most intangible. To put the horror in visible shape, no matter how gibbous or mistily, is to lessen the effect. I paint an ordinary tumble-down farmhouse with the hint of a ghastly face at a window; but this house—this house—needs no such mummery or charlatanry. It fairly exudes an aura of abnormality—that is, to a man sensitive to such impressions.”

Conrad nodded. “I received that impression from the snapshot. The trees exclude much of the building but the architecture seems very unfamiliar to me.”

“I should say so. I’m not altogether unversed in the history of architecture and I was unable to classify it. The natives say it was built by the Dutch who first settled that part of the country, but the style is no more Dutch than Greek. There’s something almost Oriental about the thing, and yet it’s not that, either. At any rate, it’s old—that cannot be denied.”

“Did you go into the house?”

“I did not. The doors and windows were locked and I had no desire to commit burglary. It hasn’t been long since I was prosecuted by a crabbed old farmer in Vermont for forcing my way into an old deserted house of his in order to paint the interior.”

“Will you go with me to Old Dutchtown?” asked Conrad suddenly.

Skuyler smiled. “I see your interest is aroused—yes, if you think you can get us into the house without having us dragged up in court afterwards. I have an eccentric enough reputation as it is; a few more suits like the one I mentioned and I’ll be looked on as a complete lunatic. And what about you, Kirowan?”

“Of course I’ll go,” I answered.

“I was sure of that,” said Conrad.

And so we came to Old Dutchtown on a warm late summer morning.

“Drowsy and dull with age the houses blink,

On aimless streets that youthfulness forget

But what time-grisly figures glide and slink

Down the old alleys when the moon has set?”

Thus Conrad quoted the phantasies of Justin Geoffrey as we looked down on the slumbering village of Old Dutchtown from the hill over which the road passed before descending into the crooked dusty streets.

“Do you suppose he had this town in mind when he wrote that?”

“It fits the description, doesn’t it—‘High gables of an earlier, ruder age,’ look—there are your Dutch houses and old Colonial buildings—I can see why you were attracted by this town, Skuyler; it breathes the very musk of antiquity. Some of those houses are three hundred years old. And what an atmosphere of decadence hovers over the whole town!”

We were met by the mayor of the place, a man whose up-to-the-minute clothes and manners contrasted oddly with the sleepiness of the town and the slow, easy-going ways of most of the natives. He remembered Skuyler’s visit there—indeed, the coming of any stranger into this little backwash town was an event to be remembered by the inhabitants. It seemed strange to think that within a hundred miles or so there roared and throbbed the greatest metropolis in the world.

Conrad could not wait a moment, so the mayor accompanied us to the house. The first glance of it sent a shudder of repulsion through me. It stood in the midst of a sort of upland, between two fertile farms, the stone fences of which ran to within a hundred yards or so on either side. A ring of tall, gnarled oaks entirely surrounded the house, which glimmered through their branches like a bare and time-battered skull.

“Who owns this land?” the artist asked.

“Why, the title is in some dispute,” answered the mayor. “Jediah Alders owns that farm there, and Squire Abner owns the other. Abner claims the house is part of the Alders farm, and Jediah is just as loud in his assertion that the Squire’s grandfather bought it from the Dutch family who first owned it.”

“That sounds backwards,” commented Conrad. “Each one denies ownership.”

“That’s not so strange,” said Skuyler. “Would you want a place like that to be part of your estate?”

“No,” said Conrad after a moment’s silent contemplation, “I wouldn’t.”

“Between ourselves,” broke in the mayor, “neither of the farmers wants to pay the taxes on the property as the land about it is absolutely useless. The barrenness of the soil extends for some little distance in all directions and the seed planted close to those stone fences on both farms yields little. These oak trees seem to sap the very life of the soil.”

“Why haven’t the trees been cut down?” asked Conrad. “I have never encountered any sentiment among the farmers of this state.”

“Why, as the ownership has been in dispute for the past fifty years, no one has taken it upon himself to cut them. And then the trees are so old and of such sturdy growth it would entail a great deal of labor. And there is a foolish superstition attached to that grove—a long time ago a man was badly cut by his own axe, trying to chop down one of the trees—an accident that might occur anywhere—and the villagers attached over-much importance to the incident. ”

“Well,” said Conrad, “if the land about the house is useless, why not rent the building itself, or sell it?”

For the first time the mayor looked embarrassed.

“None of the villagers would rent or buy it, as no good land goes with it, and to tell you the truth, it has been found impossible to enter the house!”

“Impossible?”

“Well,” he amended, “the doors and windows are heavily barred and bolted, and either the keys are in possession of someone who doesn’t care to divulge the secret, or else they’ve been lost. I have thought that possibly someone was using the house for a boot-leg den and had a reason for keeping the curious out, but no light has ever been seen there, and no one is ever seen slinking about the place.”

We had passed through the circling ring of sullen oaks and stood before the building. Seen from this vantage point, the house was formidable. It had a strange air of remoteness, as if, even though we could reach out and touch it, it stood far from us in some distant place, in another age, another time.

“I’d like to get into it,” said Skuyler.

“Try,” invited the mayor.

“Do you mean it?”

“I don’t see why not. Nobody’s bothered about the house as long as I can remember. No one’s paid taxes on the property for so long that I suppose technically it belongs to the county. It could be put up for sale, but nobody’d want it.”

Skuyler tried the door perfunctorily. The mayor watched him, a smile of amusement on his lips. Then Skuyler threw himself at the door. Not so much as a tremor moved it.

“I told you—they’re locked and barred, all the doors and windows. Short of demolishing the frame, you won’t get in.“

“I could do that,” said Skuyler.

“Perhaps,” said the mayor.

Skuyler picked up a sizable oak limb that had fallen.

“Don’t,” said Conrad suddenly.

But Skuyler had already moved forward. He ignored the door and thrust at the nearest window. He missed the frame, struck the glass, and shattered it. The oak limb came up against bars beyond.

“Don’t do it,” said Conrad again, more earnestly.

The expression on his face was baffling.

Skuyler dropped the limb in disgust.

“Don’t you feel it?” asked Conrad then.

A rush of cool air had come out of the broken window, smelling of dust and age.

“Perhaps we’d better leave it be,” said the mayor uneasily.

Skuyler backed away.

“You never can tell,” said the mayor lamely.

Conrad stood as if in a trance. Then he moved forward and bent his head in the opening in the window pane. He stood there in an attitude of listening, his eyes half closed. He braced himself against the house; I saw that his hand was trembling. “Great winds!” he whispered. “A maelstrom of winds.”

“Jim!” I said sharply.

He pulled away from the window. His face was strange. His lips were patted almost ecstatically. His eyes glittered. “I did hear something,” he said.

“You wouldn’t hear even a rat in there,” said the mayor. “They need food to stay in a place—and failing it, won’t stay.”

“Great winds,” said Conrad again, shaking his head.

“Let’s move,” said Skuyler, as if he had forgotten why we had come.

No one proposed to stay. The house had affected all of us so disagreeably that our quest was forgotten.

But Conrad had not forgotten it. As we drove away from Skuyler’s studio, after leaving the artist there, he said, “Kirowan—I’m going back there some day.”

I said nothing, neither of encouragement nor of protest, certain that he would put it out of his mind in a few days.

He said no more of Justin Geoffrey and the poet’s strange life.

It was a week before I saw Conrad again. I had forgotten the house in the oaks, and Justin Geoffrey as well. But the sight of Conrad’s drawn, haggard face, and the expression in his eyes brought Geoffrey and the house back with a rush, for I knew intuitively that Conrad had gone back there.

“Yes,” he admitted, when I put it to him. “I wanted to duplicate Geoffrey’s experience—to spend a night near the house, in the circle of oak trees. I did it. And since then—the dreams! I have not had a night free of them. I have had little sleep. I did get into the house.”

“If that inquiry into Justin Geoffrey’s life has brought you to this, Jim—forget it, give it up.”

He gave me an almost pitying look, so that it was clear to me that he thought I did not understand.

“Too late,” he said bluntly. “I came to see whether you’d take over my affairs if—if something should happen to me.“

“Don’t talk that way,” I cried, alarmed.

“It’s no good to lecture me, Kirowan,” he said. “I’ve set my affairs pretty much in order.”

“Have you seen a doctor?” I asked.

He shook his head. “There’s nothing any doctor could do, believe me. Will you do it?“

“Of course—but I hope it will never be necessary.”

He took a bulky envelope from the inner pocket of his coat. “I’ve brought you this, Kirowan. Read it when you’ve time.”

I took it. “You’ll want it back?”

“No. Keep it. Burn it when you’ve done with it. Do whatever you want with it. It doesn’t matter.”

As abruptly as he had come, he took his departure. The change in him was remarkable and profoundly disturbing.

He seemed no longer the James Conrad I had known for so many years. I watched him go with many misgivings, but I knew I could not stay his course. That extraordinary abandoned house had altered his personality to an astonishing degree—if indeed it were that. A deep depression coupled with a kind of black despair had possession of him.

I tore open the envelope at once. The manuscript inside bore, in the appearance of its script, every aspect of urgent haste.

“I want you, Kirowan, to know the events of the past week. I am sure I need hardly tell an old friend who has known me as long as you have, that I lost no time going back to that house in the oaks. (Did it ever occur to you that oaks and the Druids are closely related in folklore?) I returned the next night, and I went with crowbar and sledge and everything necessary to break down the frame of door or window so that I could get into the house. I had to get in—I knew it when I felt that uncanny draught of cold air flowing out of it. That day was warm, you’ll remember—and the air inside that closed house might have been cool, but not cold as an Arctic wind!

“It is not important to set down the agonizing details of my breaking into the house; let me say only it was as if the house fought me through every nail and splinter! But I succeeded. I took out the window Skuyler broke in his ill-advised attempt to batter his way in. (And he knew very well—he felt it, too—why he gave up so easily!)

“The interior of the house is in sharp contrast to its atmosphere. It is still furnished, and I judge that the furniture goes back at the least to the early nineteenth century; I’d guess it’s eighteenth century. All otherwise very commonplace—nothing fancy about the interior at all. But the air is cold—(I came prepared for that)—very cold, and stepping into the house was like entering another latitude. Dust, of course, and lint, and cobwebs in the corners and on the ceiling.

“Apart from the cold and the atmosphere of utter strangeness, there was one more thing—there was a skeleton sitting in a chair in what was evidently the study of the house, for there were books on the shelves. The clothes had pretty well fallen away, but what was left of them indicated that it was a man’s skeleton, as did the bones, too. I could not tell how he died, but since the house was so well locked and barred from the inside, I concluded that he had either taken his own life or had been aware that he was dying and made these preparations before death overtook him.

“But even this is not important. The presence of that skeleton there did not impress me as extraordinary—not nearly as much as the atmosphere of the house. I have mentioned the unnatural cold. Well, the very house was as unnatural inside as it appeared to be from the outside. It was, I felt at once, literally a house in another world, another dimension, separated from our own time and space and yet bound tenuously to it. How ambiguous this must sound to you!

“Let me say that at first I was aware of nothing more than the cold and the feeling of alienation. But as the night wore on, that feeling grew. I had come prepared to spend the night; I had brought flashlights, a sleeping-bag, everything I needed, even to something to drink and eat. I wasn’t tired, so the first thing I did, I explored the house. It was as ordinary upstairs and down—just about, I estimated, like any house of that period you were apt to find anywhere in New England. And yet-yet there was something subtly different—it wasn’t in the furnishings or the architecture, it was nothing you could reach out and touch, nothing you could single out and identify.

“And it grew!

“I felt it growing when I paused to look over the books on the shelves in the study. Old books. Some in Dutch—and the name on the flyleaf—(van Hoogstraten)—indicated that their owner had been Dutch—some in Latin, some in English—all very old books, some dating back to the 1300s. Books on alchemy, metallurgy, sorcery—books on occult matters, religious beliefs, superstition, witchcraft—books about strange happenings, outer worlds—books with titles like Necronomicon—De Vermin Mysteriis—Liber Ivonis—The Shadow Kingdom—Worlds Within Worlds—Unausprechlichen Kulten—De Lapide Philosophico—Monas Hieroglyphica—What Lies Beyond?—and others of similar nature. But my attention was distracted from them by a kind of vague uneasiness, a feeling as of being watched, as if I were not alone in that house.

“I stood and listened. There was nothing but the sound of wind outside—or what I took to be wind outside; but of course this was the same sound I had heard the day we were here, as I ascertained by looking out toward the oaks, which were visible in the light of the risen full moon, revealing that no twig stirred, which indicated the stillness of the air outside. So this sound was integral to the house; you may have had the experience of standing in an absolutely soundless place, and hearing the silence—a kind of ringing or muted humming sound—it has happened to me many times; it has happened to others; well, this was a similar sound, but it was undeniably a sound of wind or winds blowing far away, like the first intimation of a windstorm heard from far off, approaching and growing steadily louder. But there was no other sound—not a creak or a cracking of boards, so common to houses during changes in temperature; not the whisper of a mouse or the clicking of a beetle; nothing.

“I went back to the books, guided by the flashlight’s glow; and so I saw, as I passed between the seated skeleton and the fireplace, that something had been burned there—paper, evidently—and fragments of it lay at the edge of the hearth, not quite reduced to ashes; and, curious, I picked up some of them as carefully as I could, and examined them. They were fragments of a manuscript in Dutch, and though my knowledge of that language is not excessive, and despite a certain archaic nature of the script, I was able to read disjointed lines, which, though meaningless at the time, became more meaningful as the night made progress. Of course, there was no possibility of establishing any order among them.

“ . . . what I have done . . .

“ . . . In the beginning was chant— . . .

“ . . . at this hour the winds gave notice of His coming . . .

“ . . . house is a door to that place . . .

“ . . . He Who Will Come . . .

“ . . . breach the wall . . . co-terminous world . . .

“ . . . iron bars and recited the formulae . . .

“It seemed to me that the man who had died there, whoever he was—and there was nothing in the fragments of manuscript or the shreds of clothing that remained to identify him (presumably a former owner of the house)—being aware of the approach of death (or intending suicide), had reduced his manuscript to ashes. I examined the fireplace thoroughly; there was some evidence to show that other papers had been burned there, but nothing remained to indicate what they might have been, and I lacked the equipment to make anything more than the most cursory examination. And having done so, he prepared to die. I can only suppose that he was so reclusive by nature that no one troubled to look into his failure to appear; and that when someone did, the obviously locked and barred openings were presumptive evidence that he had gone away. Furthermore, if the skeleton is as old as I believe it to be, the neighborhood must have been very sparsely settled at the time.

“Throughout the period of my examination and transcribing of the fragments, I was aware of the wind’s sound growing louder and stronger—but it was as if it were an auditory hallucination, for there was no disturbance of the air save that minor current flowing toward the break in the wall where the window had been removed. Illusion or not, the rushing sound of the wind was unmistakable—it was as if it drove across great open spaces, for there was no hushing of leaves or trees in it, only the booming and echoing of wind in defiles and great ravines, the roaring of wind that coursed vast deserts. And there was a concomitant increase in the cold so integral to the house. But over and above this was the growing conviction of being watched, of being under scrutiny so intense that it was as if the very walls were aware of every movement that I made.

“Not surprisingly perhaps, uneasiness began to be edged with fear. I caught myself looking over my shoulder, and from time to time I crossed to the windows and looked out through the bars. I could not keep certain lines of Justin Geoffrey’s from recurring to mind—

‘They say foul things of Old Times still lurk

In Dark forgotten corners of the world,

And gates still gape to loose, on certain nights,

Shapes pent in hell. . . .’

“I tried to collect my thoughts. I sat down and concentrated with all my will on rejecting the nameless fear that pressed upon me. But I could not rest; I had to keep on the move; and that meant going to the windows from time to time. All this while, keep in mind, the wind’s sound roared around me, though I felt nothing but the cold; and all this while, too, a subtle change was taking place in my surroundings. Oh, the house and the walls, the room, the skeleton in the chair, the shelves of books were stable—but now as I looked outside I saw that a fog or a mist had risen, dimming the moon and the stars; and presently the moon and the stars winked out, and the house and I were enclosed in a well of utter blackness.

“But this did not remain. Presently it lightened. Yet the moon and the moonlight did not return. Rather, some strange hallucinatory effects began to make show. Though I could not say that I had memorized the landscape outside the house, I was at least familiar enough with Old Dutchtown and its general area to realize that the disturbing facets of countryside I now saw in that dim, iridescent glow were not natural to New England. Indeed, they were not. And once again lines of Geoffrey’s passed through—

‘Tread not where stony deserts hold

Lost secrets of an alien land,

And gaunt against the sunset’s gold

Colossal nightmare towers stand.’

For I saw great towers, I caught glimpses of tall spires, shifting and vanishing before my eyes as I looked from that house as from some vortex in space across eons of time, shifting and vanishing in great clouds of blowing sand—and then, most terrifying of all, there was at last something more.

“How can I set it down more effectively than Justin Geoffrey himself wrote it many years ago, aware of that which undoubtedly haunted his nights and days and led him to that same dream-haunted life? A child of ten he was then, when he slept near the house, within the circle of oaks—and to a child all things are part of his world, part of his nature; it was not until he grew older that he learned what he experienced that haunted night was not a part of his natural world, a revelation that troubled him so profoundly as to dog him throughout his scant years. What did he seek in that dread journey to Hungary in search of the Black Stone—if it were not tied to his experience at ten? Of what else did he write in his haunting poems? And was this not the landscape of his dreams that informed his strange verses?

‘Behind the Veil, what gulfs of Time and Space?

What blinking, mowing things to blast the sight?

I shrink before a vague, colossal Face

Born in the mad immensities of Night.’

“Thus he wrote what lay at the heart of his experience. He saw through another world, another dimension. The house in the oaks held the key; it was the door into space and time, by what alchemy or sorcery made so none can now tell, and Justin Geoffrey touched upon it as a child and accepted it until the conventions and knowledge of his own world bade him understand that the world of his dreams was utterly alien and malign.

“And he, in effect, was as much a door to that malign place in a dimension co-terminous with our own and might afford entrance to the world of men for the beings that inhabited that alien space. Was it to wonder at that he died mad? The wonder of it is that he was able to hold off madness for so long, that he could find release in his poems, those oddly disturbing lines which have come down to us to reflect the troubled mind that brought him to his ultimate end.

“For, Kirowan, I saw what he saw. I saw those great ‘blinking, mowing things’ in that weird landscape beyond the windows of that accursed house in the oaks—great, vague shapes that loomed through the blowing sand, I heard their shrieks and cries riding that wind from outer space—and, most horrible of all, I saw too the outlines of that colossal face with its eyes—eyes that flamed as with living fire—fixed upon me as certainly as I stared past the bars of the window into that alien world—saw it clearly and unmistakably, and knew it for what Geoffrey saw, before I fled that house in the early hours of the morning.

“Since then I have not slept without seeing that great face, those eyes burned on me. I know myself for its victim, as much as ever Justin Geoffrey was—but I have not had to grow into that knowledge, as he did—I know the full, cataclysmic meaning of that alien world’s impingement upon ours, and I know I cannot long sustain myself against the terrible dreams that fill the hours of my nights. . . .”

So, abruptly, his manuscript ended, and it was patent in the alteration of his script that his agitation had increased considerably from the time he had begun the writing of his account.

There is little more to tell. I made every effort to find James Conrad, but he had gone from all his accustomed haunts.

Two days later he was heard from again. The newspapers carried the story of his suicide. Before taking his own life he had traveled once more to Old Dutchtown and set fire to the house in the oaks, burning it to the ground.

I went to the site after we had buried Conrad. Nothing at all was left. It was a place of singular desolation. Even the oaks were blackened and burned. I felt, as I stood at its perimeter, an unremitting, unchanging, unearthly cold that held to it like an eternal element of the place where that forbidding house had once stood.