Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

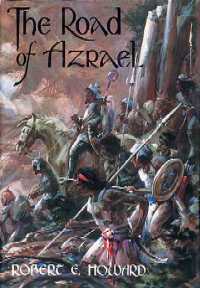

Published in The Road of Azrael, 1979. This version is taken from Howard’s original typescript.

L. Sprague de Camp edited it into the Conan story “Hawks Over Shem” (first published in Fantastic Universe, October 1955).

There also exists a shorter version.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

The tall figure in the white khalat wheeled, cursing softly, hand at scimitar hilt. Not lightly men walked the nighted streets of Cairo in the troublous days of the year 1021 ad. In this dark, winding alley of the unsavory river quarter of el Maks, anything might happen.

“Why do you follow me, dog?” The voice was harsh, edged with a Turkish accent.

Another tall figure emerged from the shadows, clad, like the first, in a khalat of white silk, but lacking the other’s spired helmet.

“I do not follow you!” The voice was not so guttural as the Turk’s, and the accent was different. “Can not a stranger walk the streets without being subjected to insult by every reeling drunkard of the gutter?”

The stormy anger in his voice was not feigned, any more than was the suspicion in the voice of the other. They glared at each other, each gripping his hilt with a hand tense with passion.

“I have been followed since nightfall,” accused the Turk. “I have heard stealthy footsteps along the dark alleys. Now you come unexpectedly into view, in a place most suited for murder!”

“Allah confound you!” swore the other wrathfully. “Why should I follow you? I have lost my way in the streets. I never saw you before, as I hope never to see you again. I am Yusuf ibn Suleyman of Cordova, but recently come to Egypt—you Turkish dog!” he added, as if impelled by overflowing spleen.

“I thought your accent betokened the Moor,” quoth the Turk. “No matter. An Andalusian sword can be bought as easily as a Cairene’s, and—”

“By the beard of Ali!” exclaimed the Moor in a gust of ungovernable passion, tearing out his saber; then a stealthy pad of feet brought him round, springing back and wheeling to keep both the Turk and the newcomers before him. But the Turk had drawn his own scimitar, and was glaring past him.

Three huge figures loomed menacingly in the shadows, the dim starlight glinting on broad curved blades. There was a glimmer, too, of white teeth, and rolling white eye-balls.

For an instant there was tense stillness; then one muttered in the thick gutturals of the Sudan: “Which is the dog? Here be two clad alike and the darkness makes them twins.”

“Cut them both down,” replied another, who towered half a head above his tall companions. “We must make no mistake, nor leave any witness.”

And so saying the three negroes came on in deadly silence, the giant advancing on the Moor, the other two on the Turk.

Yusuf ibn Suleyman did not await the attack. With a snarling oath, he ran at the approaching colossus and slashed furiously at his head. The black man caught the stroke on his uplifted blade, and grunted beneath the impact. But the next instant, with a crafty twist and wrench, he had locked the Moor’s blade under his guard and torn the weapon from his opponent’s hand, to fall ringing on the stones. A searing curse ripped from Yusuf’s lips. He had not expected to encounter such a combination of skill and brute strength.

But fired to fighting madness, he did not hesitate. Even as the giant swept the broad scimitar aloft, the Moor sprang in under his lifted arm, shouting a wild war-cry, and drove his poniard to the hilt in the negro’s broad breast. Blood spurted along Yusuf’s wrist, and the scimitar fell waveringly, to cut through his silk kafiyeh and glance from the steel cap beneath. The giant sank dying to the ground.

Yusuf ibn Suleyman caught up his saber and looked about to locate his late antagonist.

The Turk had met the attack of the two negroes coolly, retreating slowly to keep them in front of him, and suddenly slashed one across the breast and shoulder, so that he dropped his sword and fell to his knees with a moan. But even as he fell, he gripped his slayer’s knees and hung on like a brainless leech, without mind or reason. The Turk kicked and struggled in vain; those black arms, bulging with iron muscles, held him motionless, while the remaining black redoubled the fury of his strokes. The Turk could neither advance nor retreat, nor could he spare the single lightning flicker of his blade that would have rid him of his incubus.

Even as the black swordsman drew breath for a stroke that the cumbered Turk could not have parried, he heard the swift rush of feet behind him, cast a wild glance over his shoulder, and saw the Moor close upon him, eyes blazing, lips asnarl in the starlight. Before the negro could turn, the Moorish saber drove through him with such fury that the blade sprang its full length out of his breast, while the hilt smote him fiercely between the shoulders; life went out of him with an inarticulate cry.

The Turk caved in the shaven skull of the other negro with his scimitar hilt, and shaking himself free of the corpse, turned to the Moor who was twisting his saber out of the twitching body it transfixed.

“Why did you come to my aid?” inquired the Turk. Yusuf ibn Suleyman shrugged his broad shoulders at the unnecessary quality of the question.

“We were two men beset by rogues,” quoth he. “Fate made us allies. Now if you wish, we will take up anew our quarrel. You said I spied upon you.”

“And I see my mistake and crave your pardon,” answered the other promptly. “I know now who has been skulking after me down the dark alleys.”

Sheathing his scimitar, he bent over each corpse in turn, peering intently at the bloody features. When he reached the body of the giant slain by the Moor’s poniard, he paused longer, and presently murmured softly, as if to himself: “Soho! Zaman the Sworder! Of high rank the archer whose shaft is panelled with pearls!” And wrenching from the limp black finger a heavy, curiously bezelled ring, he slipped it into his girdle, and then laid hold on the garments of the dead man.

“Aid me, brother,” said he. “Let us dispose of this carrion, so that no questions will be asked.”

Without question Yusuf ibn Suleyman grasped a blood-stained jacket in each hand, and dragged the bodies after the Turk down a reeking black alley, in the midst of which rose the broken curb of a ruined and forgotten well. The corpses plunged headfirst into the abyss, and struck far below with a sullen splash, and with a light laugh, the Turk turned to the Moor.

“Allah hath made us allies,” he repeated. “I owe you a debt.”

“You owe me naught,” answered the Moor in a rather surly tone.

“Words can not level a mountain,” returned the Turk imperturbably. “I am Al Afdhal, a Memluk. Come with me out of these rat dens, and we will converse.”

Yusuf ibn Suleyman sheathed his saber somewhat grudgingly, as if he rather regretted the decision of the Turk toward peace; but he followed the latter without comment. Their way led through the rat-haunted gloom of reeking alleys, and across narrow winding streets, noisome with refuse. Cairo was then, as later, a fantastic contrast of splendor and decay, where exotic palaces rose among the smoke-stained ruins of forgotten cities; a swarm of motley suburbs clustering about the walls of El Kahira, the forbidden inner city where dwelt the caliph and his nobles.

Presently the companions came to a newer and more respectable quarter, where the overhanging balconies with their richly latticed windows of cedar and nacre inlay almost touched one another across the narrow street.

“All the shops are dark,” grunted the Moor. “A few days ago the city was lighted like day, from dusk to sunrise.”

“That was one of Al Hakim’s whims,” said the Turk. “Now he has another whim, and no lights burn in the streets of al medina. What his mood will be tomorrow, only Allah knows.”

“There is no knowledge, save in Allah,” agreed the Moor piously, and scowled. The Turk had tugged at his thin drooping moustache as if to hide a grin.

They halted before an iron-bound door in a heavy stone arch, and the Turk rapped cautiously. A voice challenged from within, and was answered in the gutturals of Turan, unintelligible to Yusuf ibn Suleyman. The door was opened, and Al Afdhal pushed into thick darkness, drawing the Moor with him. They heard the door closed behind them, then a heavy leather curtain was pulled back, revealing a lamp-lit corridor, and a scarred ancient whose fierce moustachios proclaimed the Turk.

“An old Memluk turned to wine-selling,” said Al Afdhal to the Moor. “Lead us to a chamber where we can be alone, Ahmed.”

“All the chambers are empty,” grumbled old Ahmed, limping before them. “I am a ruined man. Men fear to touch the cup, since the caliph banned wine. Allah smite him with the gout!”

Bowing them into a small chamber he spread mats for them, set before them a great dish of pistachio kernels, Tihamah raisins, and citrons, poured wine from a bulging skin, and limped away, muttering under his breath.

“Egypt has come upon evil days,” drawled the Turk lazily, quaffing deep of the Shiraz liquor. He was a tall man, leanly but strongly built, with keen black eyes that danced restlessly and were never still. His khalat was plain, but of costly fabric; his spired helmet was chased with silver, and jewels glinted in the hilt of his scimitar.

Over against him Yusuf ibn Suleyman presented something of the same hawk-like appearance, which is characteristic of all men who live by war. The Moor was fully as tall as the Turk, but with thicker limbs and a greater depth of chest. His was the build of the mountaineer—strength combined with endurance. Under his white kafiyeh his brown face showed smooth shaven, and he was lighter in complection than the Turk, the darkness of his features being more of the sun than of nature. His grey eyes in repose were cold as chilled steel, but even so there smoldered in them a hint of stormy fires.

He gulped his wine and smacked his lips in appreciation, and the Turk grinned and refilled his goblet.

“How fare the Faithful in Spain, brother?”

“Badly enough, since the Vizir Mozaffar ibn Al Mansur died,” answered the Moor. “The Caliph Hischam is a weakling. He can not curb his nobles, each of whom would set up an independent state. The land groans under civil war, and yearly the Christian kingdoms wax mightier. A strong hand could yet save Andalusia; but in all Spain there is no such strong hand.”

“In Egypt such a hand might be found,” remarked the Turk. “Here are many powerful emirs who love brave men. In the ranks of the Memluks there is always a place for a saber like yours.”

“I am neither Turk nor slave,” grunted Yusuf.

“No!” Al Afdhal’s voice was soft; the hint of a smile touched his thin lips. “Do not fear; I am in your debt, and I can keep a secret.”

“What do you mean?” The Moor’s hawk-like head came up with a jerk. His grey eyes began to smolder. His sinewy hand sought his hilt.

“I heard you cry out in the stress of the fight as you smote the black sworder,” said Al Afdhal. “You roared ‘Santiago!’ So shout the Caphars of Spain in battle. You are no Moor; you are a Christian!”

The other was on his feet in an instant, saber drawn. But Al Afdhal had not stirred; he reclined at ease on the cushions, sipping his wine.

“Fear not,” he repeated. “I have said that I would keep your secret. I owe you my life. A man like you could never be a spy; you are too quick to anger, too open in your wrath. There can be but one reason why you come among the Moslems—to avenge yourself upon a private enemy.”

The Christian stood motionless for a moment, feet braced as if for an attack, the sleeve of his khalat falling back to reveal the ridged muscles of his thick brown arm. He scowled uncertainly, and standing thus, looked much less like a Moslem than he had previously looked.

There was an instant of breathless tension, then with a shrug of his brawny shoulders, the false Moor reseated himself, though with his saber across his knees.

“Very well,” he said candidly, tearing off a great bunch of grapes with a bronzed hand and cramming them into his mouth. He spoke between mastication. “I am Diego de Guzmán, of Castile. I seek an enemy in Egypt.”

“Whom?” inquired Al Afdhal with interest.

“A Berber named Zahir el Ghazi, may the dogs gnaw his bones!”

The Turk started.

“By Allah, you aim at a lofty target! Know you that this man is now an emir of Egypt, and general of all the Berber troops of the Fatimid caliphs?”

“By Saint Pedro,” answered the Spaniard, “it matters as little as if he were a street-sweeper.”

“Your blood-feud has led you far,” commented Al Afdhal.

“The Berbers of Malaga revolted against their Arab governor,” said de Guzmán abruptly. “They asked aid of Castile. Five hundred knights marched to their assistance. Before we could reach Malaga, this accursed Zahir el Ghazi had betrayed his companions into the hands of the caliph. Then he betrayed us, who were marching to their aid. Ignorant of all that had passed, we fell into a trap laid by the Moors. Only I escaped with my life. Three brothers and an uncle fell beside me on that day. I was cast into a Moorish prison, and a year passed before my people were able to raise enough gold to ransom me.

“When I was free again, I learned that Zahir had fled from Spain, for fear of his own people. But my sword was needed in Castile. It was another year before I could take the road of vengeance. And for a year I have sought through the Moslem countries, in the guise of a Moor, whose speech and customs I have learned through a life-time of battle against them, and by reason of my captivity among them. Only recently I learned that the man I sought was in Egypt.”

Al Afdhal did not at once reply, but sat scanning the rugged features of the man before him, seeing reflected in them the untamable nature of the wild uplands where a handful of Christian warriors had defied the swords of Islam for three hundred years.

“How long have you been in al medina?” he demanded abruptly.

“Only a few days,” grunted de Guzmán. “Long enough to learn that the caliph is mad.”

“There is more to learn,” returned Al Afdhal. “Al Hakim is, indeed, mad. I say to a Feringhi what I dare not say to a Moslem—yet all men know it. The people, who are Sunnites, murmur under his heel. Three bodies of troops uphold his power. First, the Berbers from Kairouan, where this Shia dynasty of the Fatimids first took root; secondly, the black Sudani, who, under their general Othman yearly gain more power; and thirdly, the Memluks, or Baharites, the White Slaves of the River—Turks and Sunnites, like myself. Their emir is Es Salih Muhammad, and between him, and el Ghazi, and the black Othman, there is enough hate and jealousy to start a dozen wars.

“Zahir el Ghazi came to Egypt three years ago as a penniless adventurer. He has risen to emir, partly by virtue of a Venetian slave woman named Zaida. There is a woman behind the curtain of the caliph, too: the Arab Zulaikha. But no woman can play with Al Hakim.”

Diego set down his empty goblet and looked straight at Al Afdhal. Spaniards had not yet acquired the polished formality men later came to consider their dominant characteristic. The Castilian was still more Nordic than Latin. Diego de Guzmán possessed the open bluntness of the Goths who were his ancestors.

“Well, what now?” he demanded. “Are you going to betray me to the Moslems, or did you speak truth when you said you would keep my secret?”

“I have no love for Zahir el Ghazi,” mused Al Afdhal, as if to himself, turning in his fingers the ring he had taken from the black giant. “Zaman was Othman’s dog; but Berber gold can buy a Sudani sword.” Lifting his head he returned de Guzmán’s direct and challenging stare.

“I too owe Zahir a debt,” he said. “I will do more than keep your secret. I will aid you in your vengeance!”

De Guzmán started forward and his iron fingers gripped the Turk’s silk-clad shoulder like a vise.

“Do you speak truth?”

“Let Allah smite me if I lie!” swore the Turk. “Listen, while I unfold my plan—”

And while in the hidden wine-shop of Ahmed the Crippled a Turk and a Spaniard bent their heads together over a darksome plot, within the massive walls of El Kahira a stupendous event was coming to pass. Under the shadows of the meshrebiyas stole a veiled and hooded figure. For the first time in seven years, a woman was walking the streets of Cairo.

Realizing her enormity, she trembled with fear that was not inspired wholly by the lurking shadows which might mask skulking thieves. The stones hurt her feet in her tattered velvet slippers; for seven years the cobblers of Cairo had been forbidden to make street shoes for women. Al Hakim had decreed that the women of Egypt be shut up, not indeed like jewels in vaults, but like reptiles in cages.

Though clad in cast-off rags, it was no common woman who stole shuddering through the night. On the morrow the word would run through the mysterious channels of communication from harim to harim, and spiteful women lolling on satin cushions would laugh gleefully at the shame of an envied and hated sister.

Zaida, the red-haired Venetian, favorite of Zahir el Ghazi, had wielded more power than any other woman in Egypt. And now, as she stole through the night, an outcast, the thought that burned her like a white hot brand was the realization that she had aided her faithless lover and master in his climb to the high places of the world, only for another woman to enjoy the fruits of that toil.

Zaida came of a race of women accustomed to swaying thrones with their beauty and wit. She scarcely remembered the Venice from which she had been stolen as a child by Barbary pirates. The corsair who had taken her and raised her for his harim had fallen in battle with the Byzantines, and as a supple girl of fourteen, Zaida had passed into the hands of a prince of Crete, a languorous, effeminate youth, whom she came to twist about her pink fingers. Then, after some years, had come the raid of the Egyptian fleet on the islands of the Greeks, plunder, slaughter, fire, crashing walls and shrieks of death, a red-haired girl screaming in the iron arms of a laughing Berber giant.

Because she came of a race whose women were rulers of men, Zaida neither perished nor became a whimpering toy. Her nature was supple as the sapling which bends to the wind and is not uprooted. The time was not long when, if she never mastered Zahir el Ghazi in turn, she at least stood on equal footing with him, and because she came of a race of king-makers, she set forth to make a king of Zahir el Ghazi. The man had intelligence, super vitality, and strength of mind and body; he needed but one stimulant to his ambition. Zaida was that incentive.

And now Zahir, considering himself fully able to climb the shining rungs of the ladder without her, had cast her aside. Because Allah gave him a lust no one woman, however desirable, could wholly satisfy, and because Zaida would endure no rival—a supple Arab had smiled at the Berber, and the red-haired Venetian’s world had crashed. Zahir had stripped her and driven her into the street like a common slut, only the compassion of a slave covering her nakedness.

Engrossed in her searing thoughts, she looked up with a start as a tall hooded figure stepped from the shadows of an overhanging balcony and confronted her. A wide cloak was drawn close around him, his coif concealed the lower parts of his features. Only his eyes burned at her, almost luminous in the starlight. She cowered back with a low cry.

“A woman on the streets of al medina!” The voice was strange, hollow, almost ghostly. “Is this not in defiance of the command of the caliph, on whom be peace?”

“I walk not the streets by choice, ya khawand,” she answered. “My master has cast me forth, and I have not where to lay my head.”

The stranger bent his hooded head and stood statue-like for a space, like a brooding image of night and silence. Zaida watched him nervously. There was something gloomy and portentous about him; he seemed less like a man pondering over the tale of a chance-met slave-girl, than a sombre prophet weighing the doom of a sinful people.

At last he lifted his head.

“Come!” said he, in a voice of command rather than invitation. “I will find a place for you.” And without pausing to see if she obeyed, he stalked away up the street. She hurried after him, clutching her draggled robe about her. She could not walk the streets all night; any officer of the caliph would strike off her head for violating the edict of Al Hakim. This stranger might be leading her into slavery, but she had no choice.

The silence of her companion made her nervous. Several times she essayed speech, but his grim unresponsiveness struck her silent in turn. Her curiosity was piqued, her vanity touched. Never before had she failed so signally to interest a man. Faintly she sensed an imponderable something she could not overcome—an unnatural and frightening aloofness she could not touch. Fear began to grow on her, but she followed because she knew not what else to do. Only once he spoke, when, looking back, she was startled to see several furtive and shadowy forms stealing after them.

“Men follow us!” she exclaimed.

“Heed them not,” he answered in his weird voice. “They are but servants of Allah that serve Him in their way.”

This cryptic answer set her shuddering, and nothing further was said until they reached a small arched gate set in a lofty wall. There the stranger halted and called aloud. He was answered from within, and the gate opened, revealing a black mute holding a torch on high. In its lurid gleam the height of the robed stranger was inhumanly exaggerated.

“But this—this is a gate of the Great Palace!” stammered Zaida.

For answer the man threw back his hood, revealing a long pale oval of a face, in which burned those strange luminous eyes.

Zaida screamed and fell to her knees. “Al Hakim!”

“Aye, Al Hakim, oh faithless and sinful one!” The hollow voice was like a knell. Sonorous and inexorable as the brazen trumpets of doom it rolled out in the night. “Oh, vain and foolish woman, who dare ignore the command of Al Hakim, which is the word of God! Who treads the street in sin, and sets aside the mandates of The Beneficent King! There is no majesty, and there is no might save in Allah, the glorious, the great! Oh, Lord of the Three Worlds, why withhold Thy levin-fire to burn her into a charred and blackened brand for all men to behold and shudder thereat!”

Then changing his tone suddenly, he cried sharply: “Seize her!” and the dogging shadows closed in, revealing themselves as black men with the wizened features of mutes. As their fingers closed on her flesh, Zaida fainted for the first and last time in her life.

She did not feel herself being lifted and carried through the gate, across gardens waving with blossoms and reeking with spice, through corridors lined with spiral columns of alabaster and gold, and into a chamber without windows, the arched doors of which were bolted with bars of gold, gemmed with amethysts.

It was upon the carpeted, cushion strewn floor of this chamber that the Venetian regained consciousness. She looked dazedly about her, then the memory of her adventure came back with a rush, and with a low cry, she stared wildly about for her captor. She shrank down again to see him standing above her, arms folded, head bent gloomily, while his terrible eyes burned into her soul.

“Oh Lion of the Faithful!” she gasped, struggling to her knees. “Mercy! Mercy!”

Even as she spoke she was sickeningly aware of the futility of pleading for mercy where mercy was unknown. She was crouching before the most feared monarch in the world: the man whose name was a curse in the mouths of Christian, Jew and orthodox Moslem alike; the man who, claiming descent from Ali, the nephew of the Prophet, was the head of the Shia world, the Incarnation of Divine Reason to all Shiites; the man who had ordered all dogs killed, all vines cut down, all grapes and honey dumped into the Nile; who had banned all games of chance, confiscated the property of the Coptic Christians and given the people themselves over to abominable tortures; who believed that to disobey one of his commands, however trivial, was the blackest sin conceivable. He roamed the streets at night in disguise, as Haroun ar Raschid had done before him, and as Baibars did after him, to see that his commands were obeyed.

So Al Hakim stared at her with wide unblinking eyes, and Zaida felt her flesh shrivel and crawl in horror.

“Blasphemer!” he whispered. “Tool of Shaitan! Daughter of all evil! Oh Allah!” he cried suddenly, flinging aloft his wide-sleeved arms. “What punishment shall be devised for this demon? What agony terrible enough, what degradation vile enough to render justice? Allah grant me wisdom!”

Zaida rose upon her knees, snatching off her torn veil. She stretched out her arm, pointing at his face.

“Why do you call on Allah?” she shrieked hysterically. “Call on Al Hakim! You are Allah! Al Hakim is God!”

He stopped short at her cry; he reeled, catching at his head, crying out incoherently. Then he straightened himself and looked down at her dazedly. Her face was chalk white, her wide eyes staring. To her natural acting ability was added the real and desperate horror of her position. To Al Hakim it seemed that she was dazed and dazzled by a vision of celestial splendor.

“What do you see, woman?” he gasped.

“Allah has revealed Himself to me!” she whispered. “In your face, shining like the morning sun! Nay, I burn, I die in the blaze of thy glory!”

She sank her face in her hands and crouched trembling. Al Hakim passed a trembling hand over his brow and temples.

“God!” he whispered. “Aye, I am God! I have guessed it—I have dreamed it—I, and I alone possess the wisdom of the Infinite. Now a mortal has seen it, has recognized the god in the form of man. Aye, it is the truth taught by the teachers of the Shia—the Incarnation of the Godhead—I see the Truth behind the truth at last. Not a mere incarnation of divinity—divinity itself ! Allah! Al Hakim is Allah!”

Bending his gaze upon the woman at his feet, he ordered: “Rise, woman, and look upon thy god!”

Timidly she did so, and stood shrinking before his unwinking gaze. Zaida the Venetian was not extremely beautiful according to certain arbitrary standards which demand the perfectly chiselled features, the delicate frame—but she was good to look at. She was somewhat broadly built, with big breasts and haunches, and shoulders wider than most. Her face was not the classic of the Greeks, and was faintly freckled. But there was about her a vital something transcending mere superficial beauty. Her brown eyes sparkled, reflecting a keen intelligence, and the physical vigor promised by her thick limbs and big hips.

As he looked at her a change clouded the wide eyes of Al Hakim; he seemed to see her clearly for the first time.

“Thy sin is pardoned,” he intoned. “Thou wert first to hail thy God. Henceforth thou shalt serve me in honor and splendor.”

She prostrated herself, kissing the carpet before his feet, and he clapped his hands. A eunuch entered, bowing low.

“Go quickly to the house of Zahir el Ghazi,” said Al Hakim, seeming to look over the head of the servitor, and see him not at all. “Say to him: ‘This is the word of Al Hakim, who is God; that on the morrow shall be the beginning of happenings, of the building of ships, and the marshalling of hosts, even as thou hast desired; for God is God, and the unbelievers too long have blasphemed against Him!’ ”

“Hearkening and obeying, master,” mumbled the eunuch, bowing to the floor.

“I doubted and feared,” said Al Hakim dreamily, gazing far and beyond the confines of reality into some far realm only he could see. “I knew not—as now I know—that Zahir el Ghazi was the tool of Destiny. When he urged me to world-conquest, I hesitated. But I am God, and to gods all things are possible, yea, all kingdoms and glory!”

Glance briefly at the world on that night of portent, 1021 ad. It was a night in an age of change, an age writhing in the throes of labor in which all that goes to make up the modern world was struggling for birth. It was a world crimson and torn, chaotic and awful, pregnant with imponderable power, yet apparently sinking into stagnation and ruin.

In Egypt a Sunnite population groaned under the heel of a Shiite dynasty—a dynasty shrunken and shrivelled from world empire, but still mighty, reaching from the Euphrates to the Sudan. Between the borders of Egypt and the western sea stretched a vast expanse inhabited by wild tribes nominally under the caliph’s sceptre, the same tribes which had in an earlier day crushed the Gothic kingdom of Spain, and which now stirred restlessly in their mountains, needing only a powerful leader to sweep them again in an overwhelming wave against Christendom.

In Spain the divided Moorish provinces gave ground before the hosts of Castile, Leon and Navarre. But these Christian kingdoms, forged of blood and iron though they were, were not numerically powerful enough to have withstood the combined onslaught of Islam. They formed Christendom’s western frontier, while Byzantium formed the eastern frontier, as in the days of Omar and the conquering Companions, holding back the horns of the Crescent that else had met in middle Europe to form an inexorable circle. And the Crescent was never dead; it only slept, and even in its slumber throbbed the drums of empire.

Europe, in the grip of feudalism, was weaker internally than on her borders. The nations were already taking shadowy shape, but as yet there was no real national spirit. In France there was neither Charlemagne nor Martel—only starving, plague-harried peasantry, warring fiefs, and a land torn by strife between Capet and Norman duke, overlord and rebellious vassal. And France was typical of Europe.

There were, it is true, strong men in theWest: Canute the Dane, ruling Saxon England; Henry of Germany, Emperor of the shadowy Holy Roman Empire. But Canute was almost like the king of another world, in his seagirt isolation, and the Emperor had his hands full in seeking to weld his rival realms of Germany and Italy, and in beating back the encroaching Slavs.

In Byzantium the glorious reign of Basilius Bulgaroktonos was drawing to a close. Already long shadows were falling from the east across the Golden Horn. Byzantium was still Christendom’s mightiest bulwark; but westward from Bokhara were moving the horsemen of the steppes destined swiftly to wrest from the Eastern Empire her last Asiatic possession. The Seljuks, blocked on the south by the glittering Indo-Iranian empire of Mahmud of Ghazni, were riding toward the setting sun, not to be halted until their horses’ hoofs splashed the waters of the Mediterranean.

In Bagdad the Persian Buides fought in the streets with the Turkish mercenaries of the weak Abbasside caliph. But Islam was not crushed, but only broken into many parts, like the shards of a shining blade. Active strength lay in Egypt, in Ghazni, in the marauding Seljuks. Potential strength slumbered in Syria, in Irak, in Arabia, in the restless tribes of the Atlas—strength enough to burst the western barriers of Christendom, were the various separate elements united under a strong hand.

Byzantium was still unassailable; but let the Spanish kingdoms fall before a sudden onrush from Africa, and the hordes would gush into Europe almost without opposition. Such was the picture of the age: both East and West divided and inert; in the West was yet unborn that flaming spirit which, seventy-five years later, stormed eastward in the Crusades; in the East neither a Saladin nor a Genghis Khan was apparent. Yet, let such a man appear, and the horns of the revived Crescent might yet complete the circle, not in central Europe, but over the crumbling walls of Constantinople, assailed from north as well as south.

Such was the panorama of the world on that night of doom and portents, when two hooded figures halted in a group of palm trees among the ruins of nighted Cairo.

Before them lay the waters of el Khalij, the canal, and beyond it, rising from its very bank, the great bastioned wall of sun dried brick which encircled El Kahira, separating the royal heart of al medina from the rest of the city. Built by the conquering Fatimids half a century before, the inner city was in reality a gigantic fortress, sheltering the caliphs and their servants and certain troops of their mercenaries—forbidden to common men without special permit.

“We could climb the wall,” muttered de Guzmán.

“And find ourselves no nearer our enemy,” answered Al Afdhal, groping in the shadows under the clustering trees. “Here it is!”

Staring over his shoulder, de Guzmán saw the Turk fumbling at what appeared to be a shapeless heap of marble. This particular locality was occupied entirely by ruins, inhabited only by bats and lizards.

“An ancient pagan shrine,” said Al Afdhal. “Shunned because of superstition, and long crumbled—but it hides more than a grove of palm-trees shows!”

He lifted away a broad slab, revealing steps leading down into a black gaping aperture; de Guzmán frowned suspiciously.

“This,” said Al Afdhal, sensing his doubt, “is the mouth of a tunnel which leads under the wall and up into the house of Zahir el Ghazi, which stands just beyond the wall.”

“Under the canal?” demanded the Spaniard incredulously.

“Aye; once el Ghazi’s house was the pleasure house of the Caliph Khumaraweyh, who slept on an air-cushion which floated on a pool of quick-silver, guarded by lions—yet fell before the avenger’s dagger, in spite of all. He prepared secret exits from all parts of his palaces and pleasure-houses. Before Zahir el Ghazi took the house, it was occupied by his rival, Es Salih Muhammad. The Berber knows nothing of this secret way. I could have used it before, but until tonight I was not sure that I wished to slay him. Come!”

Swords drawn, they groped down a flight of stone steps and advanced along a level tunnel in pitch blackness. De Guzmán’s groping fingers told him that the walls, floor and ceiling were composed of huge blocks of stone, probably looted from edifices reared by the Pharaohs. As they advanced, the stones became slippery underfoot, and the air grew dank and damp. Drops of water fell clammily on de Guzmán’s neck, and he shivered and swore. They were passing under the canal. A little later this dankness abated somewhat, and shortly thereafter Al Afdhal hissed a warning, and they began to mount another flight of stone stairs.

At the top the Turk halted and fumbled at some bolt or catch. A panel slid aside, and a soft light streamed in from a vaulted and tapestried corridor. De Guzmán realized that they had indeed passed under the canal and the great wall, and stood in the forbidden confines of El Kahira, the mysterious and fabulous.

Al Afdhal slipped lithely through the opening, and after de Guzmán had followed, closed it behind them. It became one of the inlaid panels of the wall, differing not from the other sandalwood panels. Then the Turk went swiftly down the corridor, going without hesitation, like a man who knows his way. The Spaniard followed, saber in hand, glancing incessantly to right and left.

They passed through a dark velvet curtain and came full upon an arched doorway of gold-inlaid ebony. A brawny black man, naked but for voluminous silk breeches, who had been dozing on his haunches, started up, swinging a great scimitar. But he did not cry out; his was the bestial face of a mute.

“The clash of steel will rouse the household,” snapped Al Afdhal, avoiding the sweep of the eunuch’s sword. As the black man stumbled from his wasted effort, de Guzmán tripped him. He fell sprawling, and the Turk passed his blade through the black body.

“That was quick and silent enough!” laughed Al Afdhal softly. “Now for the real prey!”

Cautiously he tried the door, while the Spaniard crouched at his shoulder, breathing between his teeth, his eyes beginning to burn like those of a hunting cat. The door gave inward and de Guzmán sprang past the Turk into the chamber. Al Afdhal followed, and closing the door, set his back to it, laughing at the man who had leaped up from his divan with a startled oath.

“We have run the buck to cover, brother!”

But there was no laughter on the lips of Diego de Guzmán, as he stood over the half-risen occupant of the chamber, and Al Afdhal saw the lifted saber quiver in his muscular hand.

Zahir el Ghazi was a tall, lusty man, his sandy hair close cropped, his short tawny beard carefully trimmed. Late as the hour was, he was fully clad in bag-trousers of silk, girdle and velvet vest.

“Lift not your voice, dog,” advised the Spaniard. “My sword is at your throat.”

“So I see,” answered Zahir el Ghazi imperturbably. His blue eyes roved to the Turk, and he laughed with harsh mockery. “So you avoided the spillers of blood? I had thought you dead by this time. But the result will be the same. Fool! You have cut your throat! How you came into my chamber I know not; but one shout will bring my slaves.”

“Ancient houses have ancient secrets,” laughed the Turk. “One you have learned—that the walls of this chamber are so constructed as to muffle screams. Another you have not learned—the secret by which we came here tonight.” He turned to Diego de Guzmán. “Well, why do you hesitate?”

De Guzmán drew back and lowered his saber. “There lies your sword,” he said to the Berber, while Al Afdhal swore, half in disgust, half in amusement. “Take it up. If you are man enough to slay me, be it so. But I think you will never see the sun rise again.”

Zahir peered curiously at him.

“You are no Moor,” said the Berber. “I was born in the Atlas mountains, but I was raised in Malaga. You are a Spaniard. Who are you?”

Diego threw aside his tattered kafiyeh.

“Diego de Guzmán,” said Zahir calmly. “I might have guessed. Well, hidalgo, you have come a long way to die—”

He swooped up the heavy scimitar, then hesitated. “You wear armor while I am naked but for silk and velvet.”

Diego kicked a helmet toward him, one of several pieces of armor cast carelessly about the chamber.

“I see the glint of mail beneath your vest,” he said. “You always wore a steel shirt. We are on equal terms. Stand to it, you dog; my soul thirsts for your blood.”

The Berber bent, donned the head-piece—leaped suddenly, hoping to catch his antagonist off-guard. But the Moorish saber clanged in midair against the Berber scimitar, and sparks showered as the two long curved blades wheeled, flashed, rose and fell, flickering in the lamplight.

Both attacked, smiting furiously, each too intent on the life of the other to give much thought for showy sword-play. Each stroke had full weight and murderous willing behind it. Such a battle could not long continue; the desperate recklessness of the combat must quickly bring it to a bloody conclusion, one way or another.

De Guzmán fought in silence, but Zahir el Ghazi laughed and taunted his foe between lightning strokes.

“Dog!” The play of the Berber’s arm did not interfere with the play of his tongue. “It irks me to slay you here. Would that you might live to see the destruction of your accursed people. Why did I come to Egypt? Merely for refuge? Ha! I came to forge a sword for mine enemies, Christian and Moslem alike! I have urged the caliph to build a fleet—to lift the standards of jihad—to conquer the caliphate of Cordova!

“The Berber tribes are ripe for such a war. We will roar westward from Egypt like an avalanche that gains volume and momentum as it advances. With half a million warriors we will sweep into Spain—stamp Cordova into dust and incorporate its warriors into our ranks! Castile can not stand before us, and over the bodies of the Spanish knights we will sweep out into the plains of Europe!”

De Guzmán spat a curse.

“Al Hakim has hesitated,” laughed Zahir, breathing evenly and easily as he parried the whirring saber. “But tonight he sent me word—I have just come from the palace, where he told me it shall be as I have desired. He has a new whim; he believes himself to be God! No matter. Spain is doomed! If I survive, I shall be its caliph some day! And even if you slay me, you can not stop Al Hakim now. The jihad will be launched. The harims of Islam shall be filled with Castilian girls—”

From de Guzmán’s lips burst a harsh savage cry, as if he realized for the first time that the Berber was not merely taunting him with idle words, but was voicing an actual plot of conquest.

Face grey and eyes glaring, he plunged in with a fresh ferocity that made Al Afdhal stare. Zahir’s bearded lips offered no more taunts. The Berber’s whole attention was devoted to parrying the Spanish saber which beat on his blade like a hammer on an anvil.

The clash of steel rose until Al Afdhal chewed his lip in nervousness knowing that some echo of the noise would surely reverberate beyond the muffling walls.

The sheer strength and berserk fury of the Spaniard were beginning to tell. The Berber was pallid under his bronzed skin. His breath came in gasps and he continually gave ground. Blood streamed from gashes on arms, thigh, and neck. De Guzmán was bleeding too, but there was no slackening in the headlong frenzy of his attack.

Zahir was close to the tapestried wall, when suddenly he sprang aside as de Guzmán lunged. Carried off balance by the wasted thrust, the Spaniard plunged forward, and his saber-point clashed against the stone beneath the tapestry. At the same instant Zahir slashed at his enemy’s head with all his waning power. But the saber of Toledo steel, instead of snapping like a lesser blade, bent double, and sprang straight again. The descending scimitar bit through the Moorish helmet into the scalp beneath, but before Zahir could recover his balance, de Guzmán’s saber sheared upward through steel links and hip bone to grate into his spinal column.

The Berber reeled and fell with a choking cry, his entrails spilling on the floor. His fingers clawed briefly at the nap of the heavy carpet, then went limp.

De Guzmán, blind with blood and sweat, was driving his sword in silent frenzy again and again into the form at his feet, too drunk with fury to know that his foe was dead, until Al Afdhal, cursing in something nearly like horror, dragged him away. The Spaniard dazedly raked the blood and sweat from his eyes and peered down groggily at his foe. He was still dizzy from the stroke that had cloven his steel head-piece. He tore off the riven helmet and threw it aside. It was full of blood, and a crimson torrent descended into his face, blinding him.

Cursing earnestly, he began groping for something to wipe it away, when he felt Al Afdhal’s fingers at work. The Turk swiftly mopped the blood from his companion’s features, and made shift to bind up the wound with strips torn from his own clothing.

Then, taking from his girdle something which de Guzmán recognized as the ring Al Afdhal had taken from the finger of the black killer, Zaman, the Turk dropped it on the rug near Zahir’s body.

“Why did you do that?” demanded the Spaniard.

“To blind the avengers of blood. Let us go quickly, in the name of Allah. The Berber’s slaves must be all deaf or drunk, not to have awakened before now.”

Even as they emerged into the corridor, where the dead mute stared sightlessly at the painted ceiling, they heard sounds indicative of wakefulness—a vague murmur of voices, a distant tramp of feet. Hurrying down the hallway to the secret panel, they entered and groped in darkness until they emerged once more in the silent grove.

The paling stars were mirrored in the dark waters of the canal, and the first hint of dawn etched the minarets.

“Do you know a way into the palace of the caliph?” asked de Guzmán. The bandage on his head was soaked with blood, and a thin trickle stole down his neck.

Al Afdhal turned, and they faced one another under the shadow of the trees.

“I aided you to slay a common enemy,” said the Turk. “I did not bargain to betray my sovereign to you! Al Hakim is mad, but his time has not yet come. I aided you in a matter of private vengeance—not in the war of nations. Be content with your vengeance, and remember that to fly too high is to scorch one’s wings in the sun.”

De Guzmán mopped blood and made no reply.

“You had better leave Cairo as soon as possible,” said Al Afdhal, watching him narrowly. “I think it would be safer for all concerned. Sooner or later you will be detected as a Feringhi by someone not in your debt. I will furnish you with monies and horses—”

“I have both,” grunted de Guzmán, wiping the blood from his neck.

“And you will depart in peace?” demanded Al Afdhal.

“What choice have I?” returned the Spaniard.

“Swear,” insisted the Turk.

“By God, you are insistent,” grumbled de Guzmán. “Very well; I swear by Saint James of Campostello, that I will leave the city before the sun reaches its zenith.”

“Good!” The Turk breathed a sigh of relief. “It is for your own good as much as anything else that I—”

“I understand your altruistic motives,” grunted de Guzmán. “If there was any debt between us, consider it paid, and let each man act accordingly.”

And turning, he strode away with a horseman’s swinging stride. Al Afdhal watched his broad shoulder receding through the trees, with a slight frown that betokened doubt.

From mosque and minaret went forth the sonorous adan. Before the mosque of Talai, outside the Bab Zuweyla, stood Darazai, the mullah, and when he lifted his voice, and when he tolled it out across the tense throngs, men shuddered and finger nails bit into dusky palms.

“—And for that your divinely appointed caliph, Al Hakim, is of the seed of Ali, who was of the blood of the Prophet, who was God Incarnate, so is God this day among ye! Yea, the one God moves among ye in mortal shape! And now I command ye, all Believers in Al Islam, recognize and bow down and worship the one true God, Lord of the Three Worlds, the Creator of the Universe, who set up the firmament without pillars in its stead, the Incarnation of Divine Wisdom, who is God, who is Al Hakim, the seed of Ali!”

A great shudder rippled across the throng; then a frenzied yell broke the breathless stillness. A wild-haired figure ran forward, a half naked Arab. With a shriek of “Blasphemer!” he caught up a stone and hurled it. The missile struck the mullah full in the mouth, breaking his teeth. He staggered, blood streaming down his beard. And with an awesome roar, the mob heaved and billowed and surged forward. Taxation, starvation, rapine, massacre—all these the Egyptians could endure; but this stroke at the roots of their religion was the last straw. Staid merchants became madmen; cringing beggars turned into rabid-eyed devils.

Stones flew like hail, and louder and louder rose the roar, the bedlam of wild beasts, or men gone mad. Hands were clutching at the stunned Darazai’s garments, when men of the Turkish guard in chain mail and spired helmets beat the mob back with their scimitars, and carried the terrified mullah into the mosque, which they barricaded against the surging multitude.

With a clanking of weapons and a jingling of bridle-chains, a troop of Sudani horse, resplendent in gold-chased corselets and silk breeches, galloped out of the Zuweyla gate. The white teeth of the black riders shone in wide grins of glee; their eyes rolled, they licked their thick lips in anticipation. The stones of the mob rattled harmlessly on their cuirasses and hippo-hide bucklers. They urged their horses into the press, slashing with their curved blades. Men rolled howling under the stamping hoofs. The rioters gave way, fleeing wildly into shops and down alleys, leaving the square littered with writhing bodies.

The black riders leaped from their saddles and began crashing in doors of shops and dwellings, heaping their arms with plunder. Screams of women resounded from within the houses. A shriek, a crash of glass and lattice-work, and a white-clad body struck the street with a bone-crushing impact. A black face looked down through the ruined casement, split in an empty belly-shaking laugh. A black horseman spurred forward, bent from his saddle and thrust his lance through the still quivering form of the woman on the stones.

The giant Othman, in flaming silk and polished steel, rode among his black dogs, beating them off. They mounted, swung into line behind him. In a swinging canter they swept down the streets, gory human heads bobbing on their lances—an object lesson for the maddened Cairenes who crouched in their coverts, panting with hot-eyed hate.

The breathless eunuch who brought news of the uprising and its suppression to Al Hakim, was followed swiftly by another, who prostrated himself before the caliph and cried: “Oh Lord of the Three Worlds, the emir Zahir el Ghazi is dead! His servants found him murdered in his palace, and beside him the ring of Zaman the black Sworder. Wherefore the Berbers cry out that he was murdered by order of the emir Othman, and they search for Zaman in el Mansuriya, and fight with the Sudani!”

Zaida, listening behind a curtain, stifled a cry, and clutched at her bosom in brief, passing pain. But Al Hakim’s inscrutable, far-away gaze did not alter; he was wrapped in aloofness, isolated in the contemplation of mystery.

“Let the Memluks separate them,” said he. “Shall private feuds interfere with the destiny of God? El Ghazi is dead, but Allah lives. Another man shall be found to lead my troops into Spain. Meanwhile, let the building of ships commence. Let the Sudani handle the mob until they realize their folly and the sin of their heresy. I have recognized my destiny, which is to reveal myself to the world in blood and fire, until all the tribes of the earth know me and bow down before me. You have my leave to go!”

Night was falling on a tense city as Diego de Guzmán strode through the streets of the section adjoining el Mansuriya, the quarter of the Sudani. In that section, occupied mostly by soldiers, lights shone and stalls were open by tacit unspoken agreement. All day revolt had rumbled in the quarters; the mob was like a thousand-headed serpent; stamp it out in one place, and it broke out anew in another, cursing, yelling and throwing stones. The hoofs of the Sudani had clattered from Zuweyla to the mosque of Ibn Tulun and back again, spattering blood.

Only armed men now traversed the streets. The great wooden, iron-bound gates of the quarters were locked, as in times of civil war. Through the lowering arch of the great gate of Zuweyla, cantered troops of black horsemen, the torchlight crimsoning their naked scimitars. Their silk cloaks flowed in the wind, their black arms gleamed like polished ebony.

De Guzmán had not broken his oath to Al Afdhal. Sure that the Turk would betray him to the Moslems if he did not seem to comply with the other’s demand, the Spaniard had ridden out of the city, and into the Mukattam hills, before the sun was high. But he had not sworn he would not return. Sunset had seen him riding into the crumbling suburbs, where thieves and jackals slunk with furtive tread.

Now he moved on foot through the streets, entering the shops where girdled warriors gorged themselves on melons and nuts and meat, and surreptitiously guzzled wine, and he listened to their talk.

“Where are the Berbers?” demanded a moustached Turk, cramming his jaws with a handful of almond cakes.

“They sulk in their quarter,” answered another. “They swear that el Ghazi was slain by the Sudani, and display Zaman’s ring to prove it. All men know that ring. But Zaman had disappeared. The black emir Othman swears he knows naught of it. But he can not deny the ring. Already a dozen men had been killed in brawls when the caliph ordered us Memluks to beat them apart. By Allah, this has been a day of days!”

“The madness of Al Hakim has brought it about,” declared another, lowering his voice and glancing warily around. “How long shall we suffer this Shiite dog to lord it over us?”

“Have a care,” cautioned his mate. “He is caliph, and our swords are his—as long as Es Salih Muhammad so orders it. But if the revolt breaks out afresh, the Berbers are more likely to fight against the Sudani than with them. Men say that Al Hakim has taken Zaida, el Ghazi’s concubine, into his harim, and that angers the Berbers more, making them suspect that el Ghazi was slain, if not by the order of Al Hakim, at least with his consent. But Wellah, their anger is naught beside that of Zulaikha, whom the caliph has put aside! Her rage, men say, is that of a desert storm.”

De Guzmán waited to hear no more, but rising, he hastened out of the wine-shop. If anyone knew the secrets of the royal palace, that one was Zulaikha. And a discarded mistress is a sure tool for vengeance. De Guzmán’s mission had become more than a private hunt for the life of a personal enemy. Even now out of the mysterious fastnesses of the caliph’s palace rumors crept, and already in the bazaars men spoke of an invasion of Spain. De Guzmán knew that the ferocious fighting ability of the Spaniards would not, in the end, avail them against such a force as Al Hakim might be able to hurl against them. Perhaps only a madman would entertain the idea of world empire, but a madman might accomplish it; and whatever the ultimate fate of Europe, the doom of Castile was sealed if the hordes of Africa rolled up the mountain passes. De Guzmán thought little of Europe; the lands beyond the Pyrenees were dim and shadowy to him, not much more real than the empires of Alexander and the Caesars. It was Castile of which he thought, and the fierce passionate people of the savage uplands, than which no other blood beat hotly through his veins.

Skirting el Mansuriya, he crossed the canal and made his way to the grove of palms near the shore. Groping in the darkness among the marble ruins, he found and lifted the slab. Again he advanced through pitch blackness and dripping water, stumbled on the other stair and mounted it. His fingers found and worked a metal bolt, and he emerged into the now unlighted corridor. The house was silent but the reflection of lights elsewhere indicated that it was still occupied, doubtless by the slain emir’s servants and women.

Uncertain as to which way led to the outer air, he set off at random, passed through a curtained archway—and found himself confronted by half a dozen black slaves who sprang up glaring, sword in hand. Before he could retreat he heard a shout and rush of feet behind him. Cursing his luck, he ran straight at the bewildered black men. A flickering whirl of steel and he was through, leaving a writhing, bleeding form behind him, and was dashing through a doorway on the other side of the broad chamber. Curved blades were whickering at his back, and as he slammed the door behind him, steel rang on the stout oak, and glittering points showed in the splintering panels. He shot the bolt and whirled, glaring about for an avenue of escape. His gaze fell on a gold-barred window nearby.

With a headlong rush and a straining gasp of effort, he launched himself full into the window. With a splintering crash the soft bars gave way, the whole casement was torn out before the impact of his hurtling body. He shot through into empty space, just as the door crashed inward and a swarm of howling figures flooded into the room.

In the Great East Palace, where slave-girls and eunuchs glided on stealthy bare feet, no echo reverberated of the hell that raged outside the walls. In a chamber whose dome was of gold-filigreed ivory, Al Hakim, clad in a white silk robe that made him look even more ghostly and unreal, sat cross-legged on a couch of gemmed ebony, and stared with his wide unblinking eyes at Zaida the Venetian who knelt before him.

Zaida was no longer clad in the rags of a slave. Her dolyman was of crimson Mosul silk, bordered with cloth-of-gold, her girdle of satin sewn with pearls. The fabric of her wide bag drawers was sheer as gossamer, seeming to glow softly with the pink flesh it scarcely veiled. Her earrings were set with great pear-shaped jewels. Her long lashes were touched with kohl, her fingers tipped with henna. She knelt on a cloth-of-gold cushion.

But amidst all this splendor, which outshone anything even this plaything of princes had ever known, the Venetian’s eyes were shadowed. For the first time in her life she found herself actually to be a plaything. She had inspired Al Hakim’s latest madness, but she had not mastered him. A night, an hour, she had expected to bend him to her will. Now he seemed withdrawn from her, and there was an expression in his cold inhuman eyes which made her shudder.

Suddenly he spoke, ponderously, portentously, like a god voicing doom: “It is not meet that gods mate with mortals.”

She started, opened her mouth, then feared to speak.

“Love is human and a weakness,” he continued broodingly. “I will cast it from me. Gods are beyond love. And weakness assails me when I lie in your arms.”

“What do you mean, my lord?” she ventured fearfully.

“Even the gods must sacrifice,” he answered somberly. “Love of a human is blasphemy to the godhead. I give you up, lest my divinity weaken.”

He clapped his hands deliberately, and a eunuch entered on all-fours—a newly instituted custom.

“Send in the emir Othman,” ordered Al Hakim, and the eunuch bumped his head violently against the floor and backed awkwardly out of the presence.

“No!” Zaida sprang up in a frenzy. “Oh my lord, have mercy! You can not give me to that black beast! You can not—”

She was on her knees, catching at his robe, which he drew back from her fingers.

“Woman!” he thundered. “Are you mad? Would you draw doom upon yourself? Would you assail the person of God?”

Othman entered uncertainly, and in evident trepidation; a warrior of barbaric Darfur, he had risen to his present high estate by wild fighting and a brutal form of diplomacy.

Al Hakim pointed to the cowering woman at his feet and spake briefly: “Take her!”

The Sudani never questioned the commands of his monarch. A broad grin split his ebon countenance, and stooping, he caught up Zaida, who writhed and screamed in his grasp. As he bore her out of the chamber, she twisted in his arms, extending her white hands in passionate entreaty. Al Hakim answered not; he sat with hands folded, his gaze detached and impersonal as that of a hashish eater. If he heard the screams of his erstwhile favorite, he gave no sign.

But another heard. Crouching in an alcove, a slim brown-skinned girl watched the grinning Sudani carry his writhing captive up the hall. Scarcely had he vanished when she fled in another direction, garments caught up above her twinkling brown legs.

Othman, the favored of the caliph, alone of all the emirs dwelt in the Great Palace, which was really an aggregation of palaces united in one mighty structure, which housed thirty thousand servants of Al Hakim. He dwelt in a wing that opened on to the southern quarter of the Beyn el Kasreyn. To reach it, it was not necessary for him to emerge from the palace. Following winding corridors, crossing an occasional open court paved with mosaics and bordered with fretted arches supported on alabaster columns, he came to his own house.

Black swordsmen guarded the door of black teak, banded with arabesqued copper which separated his quarters from the rest of the palace. But even as he came in sight of that door, down a broad panelled corridor, a supple form glided from a curtained doorway and barred his way.

“Zulaikha!” The black recoiled in almost superstitious awe; the woman’s slim white hands clenched and unclenched in a refinement of passion too subtle and deep for his brutish comprehension; and over the filmy yasmaq her eyes burned like gems from hell.

“A servant brought me word that Al Hakim had discarded the red-haired slut,” said the Arab. “Sell her therefore to me! For I owe her a debt that I fain would pay.”

“Why should I sell her?” objected the Sudani, fidgeting in animal impatience. “The caliph has given her to me. Stand aside, woman, lest I do you an injury.”

“Have you heard what the Berbers shout in the streets?” she asked.

He started, greying slightly. “What is that to me?” he blustered, but his voice was not steady.

“They howl for the head of Othman,” she said coolly and with venom. “They call you the murderer of Zahir el Ghazi. What if I went to them and told them that what they suspect is true?”

“But I had naught to do with it!” he exclaimed wildly, like a man caught in an unseen net.

“I can produce men to swear they saw you help Zaman cut him down,” she assured him.

“I’ll kill you!” he whispered.

She laughed in his face.

“You dare not, black beast of the grass lands! Now will you sell me the red-haired jade, or will you fight the Berbers?”

His hands slipped from their hold and let Zaida fall to the floor.

“Take her and begone!” he muttered, his black skin ashen.

“Take first your pay!” she retorted with vindictive malice, and hurled a handful of coins full in his face. He shrank back like a great black ape, his eyes burning red, his dusky hands opening and closing in helpless blood-lust.

Ignoring him, Zulaikha bent over Zaida, who crouched dazed with sick helplessness, crushed by the realization of her impotence against this new conqueror, against whom, as a member of her own sex, all the witchery and wiles she had played against men were helpless. Zulaikha gathered the Venetian’s red locks in her fingers and forcing her head brutally back, stared into her eyes with a fierce and hungry possessiveness that turned Zaida’s blood to ice.

The Arab clapped her hands and four Syrian eunuchs entered.

“Take her up and bear her to my house,” Zulaikha ordered, and they laid hold of the shrinking Venetian and bore her away. Zulaikha followed, her pink nails sinking into her palms, as she breathed softly between her clenching teeth.

When Diego de Guzmán plunged through the window, he had no idea of what lay in the darkness beneath him. He did not fall far, and he crashed among shrubs that broke his fall. Springing up, he saw his pursuers crowding through the window he had just shattered, hindering one another by their numbers. He was in a garden, a great shadowy place of trees and ghostly blossoms. The next instant he was racing among the shadows, weaving in and out among the shrubbery. His hunters blundered among the trees, running aimlessly and at a loss. Unopposed he reached the wall, sprang high, caught the coping with one hand, and heaved himself up and over.

He halted and sought to orient himself. He had never been in the streets of El Kahira before, but he had heard the inner city described so often that a mental map of it was in his mind. He knew that he was in the Quarter of the Emirs, and ahead of him, over the flat roofs, loomed a great structure which could be only the Lesser West Palace, a gigantic pleasure house, giving onto the far-famed Garden of Kafur. Fairly sure of his ground, he hurried along the narrow street into which he had fallen, and soon emerged on to the broad thoroughfare which traversed El Kahira from the Gate of el Futuh in the north to the Gate of Zuweyla in the south.

Late as it was there was much stirring abroad. Armed Memluks rode past him; in the broad Beyn el Kasreyn, the great square which lay between the twin palaces, he heard the jingle of reins on restive horses, and saw a squadron of Sudani troopers sitting their steeds under the torchlight. There was reason for their alertness. Far away he heard tom-toms drumming sullenly among the quarters. Somewhere beyond the walls a dull light began to glow against the stars. The wind brought snatches of wild song and distant yells.

With his soldier’s swagger, and saber hilt thrust prominently forward, de Guzmán passed unnoticed among the mailed and weapon-girded figures that stalked the streets. When he ventured to pluck a bearded Memluk’s sleeve and inquire the way to the house of Zulaikha, the Turk gave the information readily and without surprize. De Guzmán knew—as all Cairo knew—that however much the Arab had regarded Al Hakim as her special property, she had by no means considered herself the exclusive possession of the caliph. There were mercenary captains who were as familiar with her chambers as was Al Hakim.

Zulaikha’s house stood just off the broad street, built closely adjoining a court of the East Palace, to the gardens of which indeed it was connected, so that Zulaikha, in the days of her favoritism, could pass between her house and the palace without violating the caliph’s order concerning the seclusion of women. Zulaikha was no servitor; she was the daughter of a free shaykh, and she had been Al Hakim’s mistress, not his slave.

De Guzmán did not anticipate any great difficulty in obtaining entrance into her house; she pulled hidden strings of intrigue and politics, and men of all creeds and conditions were admitted into her audience chamber, where dancing girls and opium offered entertainment. That night there were no dancing girls or guests, but a villainous looking Yemenite without question opened the arched door above which burned a cresset, and showed the false Moor across a small court, up an outer stair, down a corridor and into a broad chamber into which opened a number of fretted arches hung with crimson velvet tapestries.

The room was empty, under the soft glow of the bronze lamps, but somewhere in the house sounded the sharp cry of a woman in pain, accompanied by rich musical laughter, also in a woman’s voice, and indescribably vindictive and malicious.

But de Guzmán gave it little heed, for it was at that moment that all hell burst loose outside the walls of El Kahira.

It was a muffled roaring of incredible volume, like the bellowing of a pent-up torrent at last bursting its dam; but it was the wild beast howling of many men. The Yemenite heard too, and went livid under his swarthy skin. Then he cried out and ran into the corridor, as there sounded the swift padding of feet, and a laboring breath.

In a near-by chamber, straightening from a task she found indescribably amusing, Zulaikha heard a strangled scream outside the door, the swish and chop of a savage blow, and the thud of a falling body. The door burst open and Othman rushed in, a wild and terrifying figure, white eye balls and bared teeth gleaming in the lamplight, blood dripping from his broad scimitar.

“Dog!” she exclaimed, drawing herself up like a serpent from its coil. “What do you here?”

“The woman you took from me!” he mouthed, ape-like in his passion. “The red-haired woman! Hell is loose in Cairo! The quarters have risen! The streets will swim in blood before dawn! Kill! kill! kill! I ride to cut down the Sunnite dogs like bamboo stalks. One more killing in all this slaughter means nothing! Give me the woman before I kill you!”

Drunk with blood-hunger and frustrated lust, the maddened black had forgotten his fear of Zulaikha. The Arab cast a glance at the naked, quivering figure that lay stretched out and bound hand and foot to a divan. She had not yet worked her full will on her rival. What she had already done had been but an amusing prelude to torture, mutilation and death—agonizing only in its humiliation. All hell could not take her victim from her.

“Ali! Abdullah! Ahmed!” she shrieked, drawing a jeweled dagger.

With a bull-like roar, the huge black lunged. The Arab had never fought men, and her supple quickness, without experience or knowledge of combat, was futile. The broad blade plunged through her body, standing out a foot between her shoulders. With a choked cry of agony and awful surprize she crumpled, and the Sudani brutally wrenched his scimitar free as she fell. At that instant Diego de Guzmán appeared at the door.

The Spaniard knew nothing of the circumstances; he only saw a huge black man tearing his sword out of the body of a white woman; and he acted according to his instincts.

Othman, wheeling like a great cat, threw up his dripping scimitar, only to have it beaten stunningly down on his woolly skull beneath de Guzmán’s terrific stroke. He staggered, and the next instant the saber, wielded with all the power of the Spaniard’s knotty muscles, clove his left arm from the shoulder, sheared down through his ribs, and wedged deep in his pelvis.

De Guzmán, grunting and swearing as he twisted his blade out of the prisoning tissue and bone, sweating in fear of an attack before he could free the weapon, heard the rising thunder of the mob, and the hair lifted on his head. He knew that roar—the hunting yell of men, the thunder that has shaken the thrones of the world all down through the ages. He heard the clatter of hoofs on the streets outside, fierce voices shouting commands.

He turned toward the outer corridor when he heard a voice begging for something, and wheeling back into the chamber, saw, for the first time, the naked figure writhing on the divan. Her limbs and body showed neither gash nor bruise, but her cheeks were wet with tears, the red locks that streamed in wild profusion over her white shoulders were damp with perspiration, and her flesh quivered as if from torture.

“Free me!” she begged. “Zulaikha is dead—free me, in God’s name!”

With a muttered oath of impatience he slashed her cords and turned away again, almost instantly forgetting about her. He did not see her rise and glide through a curtained doorway.

Outside a voice shouted: “Othman! Name of Shaitan, where are you? It is time to mount and ride! I saw you run in here! Devil take you, you black dog, where are you?”

A mailed and helmeted figure dashed into the chamber, then halted short.

“What—? Wellah! You lied to me!”

“Not I!” responded de Guzmán cheerfully. “I left the city as I swore to do; but I came back.”

“Where is Othman?” demanded Al Afdhal. “I followed him in here—Allah!” He plucked his moustaches wildly. “By God, the One True God! Oh, cursed Caphar! Why must you slay Othman? All the cities have risen, and the Berbers are fighting the Sudani, who had their hands full already. I ride with my men to aid the Sudani. As for you—I still owe you my life, but there is a limit to all things! In Allah’s name, get you gone, and never let me see you again!”

De Guzmán grinned wolfishly. “You are not rid of me so easily this time, Es Salih Muhammad!”

The Turk started. “What?”

“Why continue this masquerade?” retorted de Guzmán. “I knew you when we went into the house of Zahir el Ghazi, which was once the house of Es Salih Muhammad. Only a master of the house could be so familiar with its secrets. You helped me kill el Ghazi because the Berber had hired Zaman and the others to kill you. Good enough. But that is not all. I came to Egypt to kill el Ghazi; that is done; but now Al Hakim plots the ruin of Spain. He must die; and you must aid me in his overthrow.”

“You are mad as Al Hakim!” exclaimed the Turk.

“What if I went to the Berbers and told them that you aided me to slay their emir?” asked de Guzmán.

“They would cut you to pieces!”

“Aye, so they would! But they would likewise cut you to pieces. And the Sudani would aid them; neither loves the Turks. Berbers and blacks together will cut down every Turk in Cairo. Then where is your ambition, when your head is off? I will die, yes; but if I set Sudani, Turk and Berber to slaying each other, perchance the rebellion will whelm them all, and I will have gained in death what I could not in life.”

Es Salih Muhammad recognized the grim determination which lay behind the Castilian’s words.

“I see I must slay you, after all!” he muttered, drawing his scimitar. The next instant the chamber resounded to the clash of steel.

At the first pass de Guzmán realized that the Turk was the finest swordsman he had ever met; he was ice where the Spaniard was fire. To his reluctance to kill Es Salih was added the knowledge that he was opposed by a greater swordsman than himself. And the thought nerved him to desperate fury, so that the headlong recklessness that had always been his weakness, became his strength. His life did not matter; but if he fell in that blood-stained chamber, Castile fell with him.

Outside the walls of El Kahira the mob surged and ravened, torches showered sparks, and steel drank and reddened. Inside the chamber of dead Zulaikha the curved blades sang and whistled. Smite, Diego de Guzmán! (they sang). Spain hangs on your arm. Strike for the glories of yesterday and the splendors of tomorrow. Strike for the thunder of arms, the rustle of banners in the mountain winds, the agony of endeavor, and the blood of martyrdom; strike for the spears of the uplands, the black-haired women, fires on the red hearths, and the trumpets of empires yet to be! Strike for the unborn kingdoms, the pageantry of glory, and the great galleons rolling across a golden sea to a world undreamed! Strike for the wonder that is Spain, aged and ever ageless, the phoenix of nations, rising for ever from the ashes of a dead past to burn among the standards of the world!

Through his parted lips Es Salih Muhammad’s breath hissed. Under his dark skin grew an ashy hue. Skill nor craft availed him against this blazing-eyed incarnation of fury who came on in an irresistible surge, smiting like a smith on an anvil.

Under the brown-crusted bandage de Guzmán’s wound was bleeding afresh, and the blood poured down his temple, but his sword was like a flaming wheel. The Turk could only parry; he had no opportunity to strike back.

Es Salih Muhammad was fighting for personal ambition; Diego de Guzmán was fighting for the future of a nation.

A last gasping heave of thew-wrenching effort, an explosive burst of dynamic power, and the scimitar was beaten from the Turk’s hand. He reeled back with a cry, not of pain or fear, but of despair. De Guzmán, his broad breast heaving from his exertions, turned away.

“I will not cut you down myself,” he said. “Nor will I force an oath from you at sword’s edge. You will not keep it. I go to the Berbers, and my doom—and yours. Farewell; I would have made you vizir of Egypt!”

“Wait!” panted Es Salih, grasping at a hanging for support. “Let us reason this matter! What do you mean?”

“What I say!” De Guzmán wheeled back from the door, galvanized with a feeling that he had the desperate game in his hand at last. “Do you not realize that at the instant you hold the balance of power? The Sudani and Berbers fight each other, and the Cairenes fight both! Neither faction can win without your support. The way you throw your Memluks will be the deciding factor. You planned to support the Sudani and crush both the Berbers and the rebels. But suppose you threw in your lot with the Berbers? Suppose you appeared as the leader of the revolt, the upholder of the orthodox creed against a blasphemer? El Ghazi is dead; Othman is dead; the mob has no leader. You are the only strong man left in Cairo. You sought honors under Al Hakim; greater honors are yours for the asking! Join the Berbers with your Turks, and stamp out the Sudani! The mob will acclaim you as a liberator. Kill Al Hakim! Set up another caliph, with yourself as vizir, and real ruler! I will ride at your side, and my sword is yours!”

Es Salih, who had been listening like a man in a dream, gave a sudden shout of laughter, like a drunken man. Realization that de Guzmán wished to use him as a pawn to crush a foe of Spain was drowned in the heady wine of personal ambition.

“Done!” he trumpeted. “To horse, brother! You have shown me the way I sought! Es Salih Muhammad shall yet rule Egypt!”

In the great square of el Mansuriya, the tossing torches blazed on a maelstrom of straining, plunging figures, screaming horses, and lashing blades. Men brown, black and white fought hand-in-hand, Berber, Sudani, Egyptian, gasping, cursing, slaying and dying.

For a thousand years Egypt had slept under the heel of foreign masters; now she awoke, and crimson was the awakening.

Like brainless madmen the Cairenes grappled the black slayers, dragging them bodily from their saddles, slashing the girths of the frenzied horses. Rusty pikes clanged against lances. Fire burst out in a hundred places, mounting into the skies until the herdsmen on Mukattam awoke and gaped in wonder. From all the suburbs poured wild and frantic figures, a roaring torrent with a thousand branches all converging on the great square. Hundreds of still shapes, in mail or striped kaftans, lay under the trampling hoofs, the stamping feet, and over them the living screamed and hacked.

The square lay in the heart of the Sudani quarter, into which had come ravening the blood-mad Berbers while the bulk of the blacks had been fighting the mob in other parts of the city. Now, withdrawn in haste to their own quarter, the ebony swordsmen were overwhelming the Berbers with sheer numbers, while the mob threatened to engulf both hordes. The Sudani, under their captain Izz ed din, maintained some semblance of order, which gave them an advantage over the unorganized Berbers and the leaderless mob.

The maddened Cairenes were smashing and plundering the houses of the blacks, dragging forth howling women; the blaze of burning buildings made the square swim in an ocean of fire.

Somewhere there began the whir of Tatar kettle-drums, above the throb of many hoofs.

“The Turks at last,” panted Izz ed din. “They have loitered long enough! And where in Allah’s name is Othman?”

Into the square raced a frantic horse, foam flying from the bit-rings. The rider reeled in the saddle, gay-hued garments in tatters, ebony skin laced with crimson.

“Izz ed din!” he screamed, clinging to the flying mane with both hands. “Izz ed din!”

“Here, fool!” roared the Sudani, catching the other’s bridle and hurling the horse back on its haunches.

“Othman is dead!” shrieked the man above the roar of the flames and the rising thunder of the onrushing kettle-drums. “The Turks have turned on us! They slay our brothers in the palaces! Aie! They come!”