Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

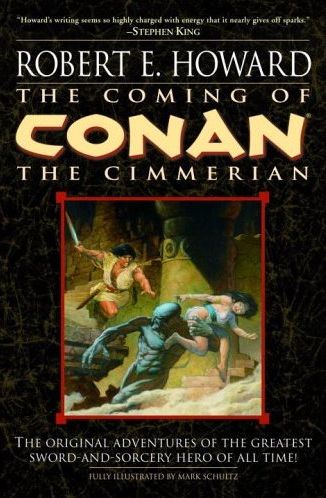

Published in The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian, 2003, as “Untitled Fragment”

(the “Hand . . .” title is from the version Lin Carter completed and published 1968).

The same title was apparently used when the fragment was first published, in The Last Celt 1976.

| 1. | 2. |

The battlefield stretched silent, crimson pools among the still sprawling figures seeming to reflect the lurid red-streamered sunset sky. Furtive figures slunk from the tall grass; birds of prey dropped down on mangled heaps with a rustle of dusky wings. Like harbingers of Fate a wavering line of herons flapped slowly away toward the reed-grown banks of the river. No rumble of chariot-wheel or peal of trumpet disturbed the unseeing stillness. The silence of death followed the thundering of battle.

Yet one figure moved through that wide-strewn field of ruin—pygmy-like against the vast dully crimson sky. The fellow was a Cimmerian, a giant with a black mane and smoldering blue eyes. His girdled loin-cloth and high-strapped sandals were splashed with blood. The great sword he trailed in his right hand was stained to the cross-piece. There was a ghastly wound in his thigh, which caused him to limp as he walked. Carefully yet impatiently he moved among the dead, limping from corpse to corpse, and swearing wrathfully as he did so. Others had been before him; not a bracelet, gemmed dagger, or silver breastplate rewarded his search. He was a wolf who had lingered too long at the blood-letting, while jackals stripped the prey.

Glaring out across the littered plain, he saw no body unstripped or moving. The knives of the mercenaries and camp-followers had been at work. Straightening up from his fruitless quest, he glanced uncertainly afar off across the deepening plain, to where the towers of the city gleamed faintly in the sunset. Then he turned quickly as a low tortured cry reached his ears. That meant a wounded man, living, therefore presumably unlooted. He limped quickly toward the sound, and coming to the edge of the plain, parted the first straggling reeds and glared down at the figure which writhed feebly at his feet.

It was a girl that lay there. She was naked, her white limbs cut and bruised. Blood was clotted in her long dark hair. There was unseeing agony in her dark eyes and she moaned in delirium.

The Cimmerian stood looking down at her, and his eyes were momentarily clouded by what would have been an expression of pity in another man. He lifted his sword to put the girl out of her misery, and as the blade hovered above her, she whimpered again like a child in pain. The great sword halted in midair, and the Cimmerian stood for an instant like a bronze statue. Then sheathing the blade with sudden decision, he bent and lifted the girl in his mighty arms. She struggled blindly but weakly. Carrying her carefully, he limped toward the reed-masked river-bank some distance away.

In the city of Yaralet, when night came on, the people barred windows and bolted doors, and sat behind their barriers shuddering, with candles burning before their household gods until dawn etched the minarets. No watchmen walked the streets, no painted wenches beckoned from the shadows, no thieves stole nimbly through the winding alleys. Rogues, like honest people, shunned the shadowed ways, gathering in foul-smelling dens, or candle-lighted taverns. From dusk to dawn Yaralet was a city of silence, her streets empty and desolate.

Exactly what they feared, the people did not know. But they had ample evidence that it was no empty dream they bolted their doors against. Men whispered of slinking shadows, glimpsed from barred windows—of hurrying shapes alien to humanity and sanity. They told of doorways splintering in the night, and the cries and shrieks of humans followed by significant silence; and they told of the rising sun etching broken doors that swung in empty houses, whose occupants were seen no more.

Even stranger, they told of the swift rumble of phantom chariot-wheels along the empty streets in the darkness before dawn, when those who heard dared not look forth. One child looked forth, once, but he was instantly stricken mad and died screaming and frothing, without telling what he saw when he peered from his darkened window.

On a certain night, then, while the people of Yaralet shivered in their bolted houses, a strange conclave was taking place in the small velvet-hung taper-lighted chamber of Atalis, whom some called a philosopher and others a rogue. Atalis was a slender man of medium height, with a splendid head and the features of a shrewd merchant. He was clad in a plain robe of rich fabric, and his head was shaven to denote devotion to study and the arts. As he talked he unconsciously gestured with his left hand. His right arm lay across his lap at an unnatural angle. From time to time a spasm of pain contorted his features, at which time his right foot, hidden under the long robe, would twist back excrucriatingly upon his ankle.

He was talking to one whom the city of Yaralet knew, and praised, as Prince Than. The prince was a tall lithe man, young and undeniably handsome. The firm outline of his limbs and the steely quality of his grey eyes belied the slightly effeminate suggestion of his curled black locks, and feathered velvet cap.