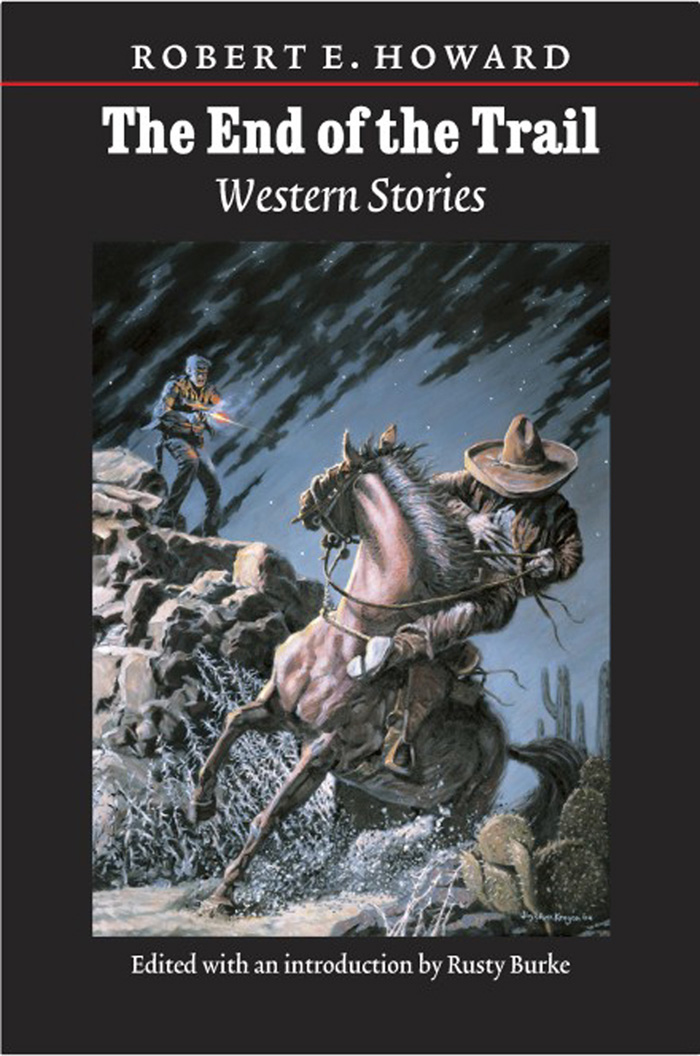

Cover from the collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in The Tattler (the Brownwood High School paper), 22 December 1922,

though here taken from the 2005 collection The End of the Trail: Western Stories.

| Chapter I | Chapter II |

Red Ghallinan was a gunman. Not a trade to be proud of, perhaps, but Red was proud of it. Proud of his skill with a gun, proud of the notches on the long blue barrels of his heavy .45’s. Red was a wiry, medium sized man with a cruel, thin lipped mouth and close-set, shifty eyes. He was bow-legged from much riding, and, with his slouching walk and hard face he was, indeed, an unprepossessing figure. Red’s mind and soul were as warped as his exterior. His sinister reputation caused men to strive to avoid offending him but at the same time it cut him off from the fellowship of people. No man, good or bad, cares to chum with a killer. Even the outlaws hated him and feared him too much to admit him to their gang, so he was a lone wolf. But a lone wolf may sometimes be more feared than the whole pack.

Let us not blame Red too much. He was born and reared in an environment of evil. His father and his father’s father had been rustlers and gunfighters. Until he was a grown man, Red knew nothing but crime as a legitimate way of making a living and by the time he learned that a man may earn a sufficient livelihood and still remain within the law he was too set in his ways to change. So it was not altogether his fault that he was a gunfighter. Rather, it was the fault of those unscrupulous politicians and mine-owners who hired him to kill their enemies. For that was the way Red lived. He was born a gun-fighter. The killer instinct burned strongly in him—the heritage of Cain. He had never seen the man who surpassed him or even equalled him in the speed of the draw or in swift, straight shooting. These qualities, together with the cold nerve and reckless bravery that goes with red hair, made him much in demand with rich men who had enemies. So he did a large business.

But the fore-van of the law began to come into Idaho and Red saw with hate the first sign of that organization which had driven him out of Texas a few years before—the vigilantes. Red’s jobs became fewer and fewer for he feared to kill unless he could make it appear self-defense.

At last it reached a point where Red was faced with the alternative of moving on or going to work. So he rode over to a miner’s cabin and announced his intention of buying the miner’s claim. The miner, after one skittish glance at Red’s guns, sold his claim for fifty dollars, signed the deed, and left the country precipitately.

Red worked the claim for a few days and then quit in disgust. He had not gotten one ounce of gold dust. This was due, partly, to his distaste for work, partly to his ignorance of placer mining, and mostly to the poorness of the claim.

He was standing in the front door of the saloon of the little mining town when the stage-coach drove in and a passenger alit.

He was a well built, frank-appearing young fellow and Red hated him instinctively. Hated him for his cleanness, for his open, honest, pleasant face, because he was everything Red was not.

The newcomer was very friendly and very soon the whole town knew his antecedents. His name was Hal Sharon, a tenderfoot from the east, who had come to Idaho with high hopes of striking a bonanza and going home wealthy. Of course there was a girl in the case, though Hal said little on that point. He had a few hundred dollars and wanted to buy a good claim. At this Red took a new interest in the young man.

Red bought drinks and lauded his claim. Sharon proved singularly trustful. He did not ask to see the claim but took Red’s word for it. A trustfulness that would have touched a less hardened man than Red.

One or two men, angered at the deliberate swindle, tried to warn Hal but a cold glance from Red caused them to change their minds. Hal bought Red’s claim for five hundred dollars.

He toiled unceasingly all fall and early winter, barely making enough to keep him in food and clothes, while Red lived in the little town and sneered at his uncomplaining efforts.

Christmas was in the air. Everywhere the miners stopped work and came to town to live there until the snow should have melted and the ground thawed out in the spring. Only Hal Sharon stayed at his claim, working on in the cold and snow, spurred on by the thought of riches—and a girl.

It was a little over three weeks until Christmas, when, one cold night, Red Ghallinan sat by the stove in the saloon and listened to the blizzard outside. He thought of Sharon doubtless shivering in his cabin up on the slopes and he sneered. He listened idly to the talk of the miners and cowpunchers who were discussing the coming festivals, a dance and so on.

Christmas meant nothing to Red. Though the one bright spot in his life had been one Christmas years ago when Red was a ragged waif, shivering on the snow covered streets of Kansas City.

He had passed a great church and, attracted by the warmth, had entered timidly. The people had sung “Hark the Herald Angels Sing!” and when the congregation passed out, an old, white-haired woman had seen the boy and had taken him home and fed him and clothed him. Red had lived in her home as one of the family until spring but when the wild geese began to fly north and the trees began to bud, the wanderlust got into the boy’s blood and he ran away and came back to his native Texas prairies. But that was years ago and Red never thought of it now.

The door flew open and a furred and muffled figure strode in. It was Sharon—his hands shoved deep in his coat pockets.

Instantly Red was on his feet, hand twisting just above a gun. But Hal took no notice of him. He pushed his way to the bar.

“Boys,” he said, “I named my claim the Golden Hope, and it was a true name! Boys, I’ve struck it rich!”

And he threw a double handful of nuggets and gold-dust on the bar.

On Christmas Eve Red stood in the door of an eating house and watched Sharon coming down the slope, whistling merrily. He had a right to be merry. He was already worth twelve thousand dollars and had not exhausted his claim by half. Red watched with hate in his eyes. Ever since the night Sharon had thrown his first gold on the bar, his hatred of the man had grown. Hal’s fortune seemed a personal injury to Red. Had he not worked like a slave on that claim without getting a pound of gold? And here this stranger had come and gotten rich off that same claim! Thousands to him, a measly five hundred to Red. To Red’s warped mind this assumed monstrous proportions—an outrage. He hated Sharon as he had never hated a man before. And, since with him to hate was to kill, he determined to kill Hal Sharon. With a curse he reached for a gun when a thought stayed his hand. The Vigilantes! They would get him sure if he killed Sharon openly. A cunning light came to his eyes and he turned and strode away toward the unpretentious boarding-house where he stayed.

Hal Sharon walked into the saloon.

“Seen Ghallinan lately?” he asked.

The bar-tender shook his head.

Hal tossed a bulging buck-skin sack on the bar.

“Give that to him when you see him. It’s got about a thousand dollars worth of gold dust in it.”

The bar-tender gasped. “What! You giving Red a thousand bucks after he tried to swindle you? Yes, it is safe here. Ain’t a galoot in camp would touch anything belonging to that gun-fighter. But say—”

“Well,” answered Hal, “I don’t think he got enough for his claim; he practically gave it to me. And anyway,” he laughed over his shoulder, “it’s Christmas!”

Morning in the mountains. The highest peaks touched with a delicate pink. The stars paling as the darkness grew grey. Light on the peaks, shadow still in the valleys, as if the paint brush of the Master had but passed lightly over the land, coloring only the highest places, the places nearest to Him. Now the light-legions began to invade the valleys, driving before them the darkness; the light on the peaks grew stronger, the snow beginning to cast back the light. But as yet no sun. The King had sent his couriers before him but he himself had not appeared.

In a certain valley, smoke curled from the chimney of a rude log cabin. High on the hillside, a man gave a grunt of satisfaction. The man lay in a hollow, from which he had scraped the drifted snow. Ever since the first hint of dawn, he had lain there, watching the cabin. A heavy rifle lay beneath his arm.

Down in the valley, the cabin door swung wide and a man stepped out. The watcher on the hill saw that it was the man he had come to kill.

Hal Sharon threw his arms wide and laughed aloud in the sheer joy of living. Up on the hill, Red Ghallinan watched the man over the sights of a Sharps .50 rifle. For the first time he noticed what a magnificent figure the young man was. Tall, strong, handsome, with the glow of health on his cheek.

For some reason Red was not getting the enjoyment he thought he would. He shook his shoulders impatiently. His finger tightened on the trigger—suddenly Hal broke into song; the words floated clearly to Red.

“Hark the Herald Angels Sing!”

Where had he heard that song before? Then suddenly a mist floated across Red Ghallinan’s eyes; the rifle slipped unnoticed from his hands. He drew his hand across his eyes and looked toward the east. There, alone, hung one great star and as he looked, over the shoulder of a great mountain came the great sun.

“Gawd!” gulped Red, “why—it is Christmas!”