Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

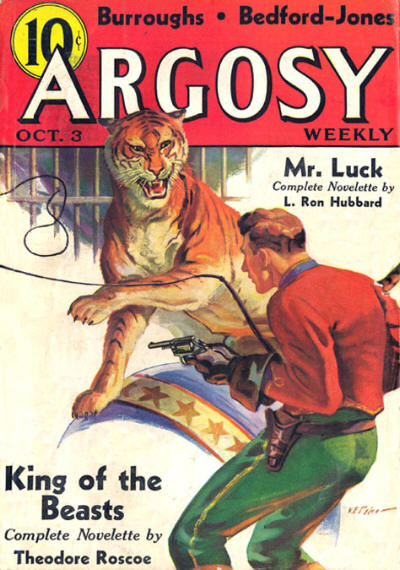

Published in Argosy, Vol. 267, No. 5 (3 October 1936).

I was in the Buckhorn Saloon in San Antonio, jest h’isting a schooner of Pearl XXX, when my brother Kirby come staggering in all caked with dust and sweat, and stuck out a letter at me.

“Pap sent it,” he gasped. “I’ve rode day and night to find you!” He then collapsed onto the floor where he lay till I picked him up and laid him on the bar and started the barkeep to pouring licker down his throat. It’s a long way from our cabin to Santone, and he must of had a hard ride. I figgered the letter he brung must be arful important, so after I’d drunk my beer and et me a sandwich offa the free lunch counter, I onfolded it and read it. It was from Aunt Navasota Hawkins, over in East Texas, and it was addressed to Mister Judson Bearfield, Wolf Mountain, Texas, which is Pap, and it said:

Dear Jud:

We air in awful trouble. Somethin happened none of us never drempt could happen. Uncle Joab Hudkins has took to stealin hawgs! You won’t believe this I know Judson because none of the family never stole nothin in their life before but it’s the truth. The Watsons ketched him in their pigpen tother night and filled his britches with bird-shot and I will not repeat his langwidge whilst we was picking them shot out of his hide Judson. The whole clan gathered around and argyed with him Judson but we wouldn’t move him all he said was he wisht we would mind our own dadburned business. He was very cantankerus Judson and you ought to of heard what he called Uncle Saul Hawkins when Uncle Saul told him he had disgraced the family.We could not do nothin with him so we left Cousin Esau Harrison to see he didn’t git out of the house till we could decide what to do. But he hit Cousin Esau over the head with the axe handle I use to stir hominy with and has run off into the woods Judson it is tarrible we don’t know what he’s up to but we suspects the wust. We have apolergized to the Watsons and offered to pay them for any damage he done but you know how them Watsons is Judson they say nothin will wipe out the insult but blood. It looks like they air goin to force a feud onto us we have got enough feuds as it is Judson. And so will you please send Pikeston over here to help find Uncle Joab and settle them Watsonses’ hash.

Yore lovin Ant Navasota Hawkins

On the bottom of her letter Pap had writ, “Pike, pull for Choctaw Bayou as fast as you can peel it and don’t take no sass from them cussed Watsons.”

Well, I was so overcame for a few minutes all I could do was lean on the bar and drink a pint of tequila. To think as a relative of mine would stoop to pig stealing! Why, us Bearfields was that proud we wouldn’t even steal a hoss. I dunno when I ever felt so low and wolfish in my spirits. I felt like the whole world knowed our shame and was p’inting the finger of scorn at us.

When Kirby come to he said he felt the same, and he said he aimed to shoot the first illegitimate which even said “hawg” at him. But I cautioned him to guard our arful secret with his life, and I told him to go around to the wagon yard where my hoss Satanta was, and arrange for his board whilst I was gone.

I then bought me a ticket for Houston and clumb aboard the train without telling my friends good-by; I was too ashamed to look ’em in the face with a pig thief in the family.

That was a irksome journey. All I could think of was pigs and when I dozed in my seat I dreampt about pigs. It was a dark hour for the Bearfield pride, and I got tetchier every minute.

When I got to Houston I imejitly went to a livery stable to rent me a hoss, and there I run into the same difficulty I always run into whenever I gits east of the Trinity. They warn’t a hoss in town which was big enough and strong enough to tote my weight any distance. I dunno why them folks raises sech spindly critters. They claims their hosses is all right, and I’m jest bigger’n a human being ought to be. Well, I ain’t considered onusually gigantic on Wolf Mountain, but I have already noticed that men on Wolf Mountain grows bigger’n they does in most places. So I reckon I do look kind of prominent to strangers, being as I stand six foot nine in my socks and weigh two hundred and ninety-five pounds, all bone and muscle. In addition to which modesty forces me to remark that I’m jest about the best man in a free-for-all on Wolf Mountain or anywheres else that I ever been, either.

Anyway, I finally pitched on a squint-eyed mule named Sinclair’s Defeat, which was big enough even for me, and I forked him and headed for the home-range of my erring relative. I was in the piney-woods by now, and I felt plumb smothered with all them trees and sloughs and swamps, and no hills nor prickly pears nor prairies.

Them woods was full of razorback hawgs and every time I seen one it reminded me of the family shame, so I was in a regular welter of nervous irritation time I got to Sabineville, where my kinfolks does their trading. It was about noon, so I put Sinclair’s Defeat in the wagon yard and seen he was fed and watered, and then I went to the restaurant. I hadn’t been to Sabineville since I was a kid, and didn’t know nobody there, but everybody I met stopped and gaped like they never seen a man my size before. They all had their guns on under their shirts and so did I, because I hid mine when we pulled into Houston.

I sot down in the restaurant and the waiter ast me what I’d have. I ast him what he had, and he says, “We got some nice roast pork!”

“Listen here, you!” I says, rising in wrath. “Maybe you think you can mock me with impunity because I’m a stranger in yore midst. But the man don’t live which can throw the family scandal in my face and survive!”

“What air you talkin’ about?” gasped he, recoiling.

“Don’t try to ack innercent,” I says bitterly. “I don’t know you, and I don’t know how come you to recognize me, but the best thing you can do is to pertend not to know me. Bring me a beefsteak smothered with onions and nine or ten bottles of beer, and lemme hear no more about pork if you values yore wuthless life!”

He done so in fear and trembling, and I heard him whisper to the cook that they was a homicidal maneyack outside; but I didn’t see none.

I’d jest started on my steak when three big, rough-looking men come in. They give me a suspicious glance, but I paid ’em no heed and went on eating. So they sot down at the counter and ordered beans and coffee, and one of ’em said, “Have you swore out that warrant for old Joab Hudkins yet, Jabez?”

They all looked around at me on account of me strangling on my beer, and the oldest and meanest-looking one says, “I’m goin’ over to the sheriff ’s office soon’s we’ve et, Bill. This is the chance I been lookin’ fur.”

“Suits me,” says Bill with a oath. “Hey, Joe?”

“Shore,” says the third ’un. “But we better be keerful. Them Hudkinses and their kinfolks around here is bad enough, but the Bearfields, which lives out beyond the Pecos somewheres, is wuss yet.”

“I ain’t scairt of ’em,” says Jabez. “Ain’t us Watsons won all our feuds up to now? I don’t keer nothin’ about the hawgs, neither. But this here’s my chance to git even with old Esau Hawkins for that whuppin’ he give me over to the county seat fifteen year ago. I jest want to see his face when one of his kin goes to the pen for stealin’ hawgs! . . . What was that?”

It was me, tying a knot in my steak fork in my struggle to control myself, but by a supreme effort I helt my peace.

“Well,” says Bill, “I hopes for Hudkins gore! I jest wisht one of them tough Bearfields was here. I’d show him a thing or two, I betcha!”

“Well, git the exhibition started!” I said, heaving up so sudden I upsot my table and Joe fell off his stool. “I’ve stood all I can from you illegitimates.”

“Who the devil air you?” gasped Jabez, jumping up, and I says, “I’m a Bearfield from the Pecos, and Joab Hudkins is my kin! I’m askin’ you like a gent to refrain from swearin’ out that warrant you all was talkin’ about I’m here to see that he don’t molest nobody else’s hawgs, but I ain’t goin’ to see him tromped on, neither!”

“Oh, ain’t you?” sneered Bill, fingering his pistol, whilst I seen Joe sneaking a bowie outa his boot. “Well, lemme tell you somethin’, you dern mountain grizzly, we aims to put that there pig snatchin’ uncle of yore’n behind the bars! How you like that, hey?”

“This is how much, you blasted swamp rat!” I roared, shattering my steak plate over his head.

He fell offa his stool howling bloody murder, and Joe made a stab at me but missed and stuck his knife in the table and whilst he was trying to pull it out I busted the catsup bottle over his head and he j’ined Bill on the floor. I then seen Jabez crouching at the end of the counter fixing to shoot me with his pistol, so I grabbed a case of canned tomaters and throwed it at him, and what happened to the waiter was his own fault. He oughta stayed outa the fight in the first place. If he hadn’t been trying to git a shotgun he had behind the counter he wouldn’t of run between me and Jabez jest as I heaved that case of vegetables. T’warn’t my fault he got hit in the head, no more’n it was my fault he ketched old Jabez’s bullet in his hind laig, neither. I kicked Jabez’s pistol out of his hand before he could shoot again, and he run around behind the counter on his all-fours, jest as the cook come out of the kitchen with a iron skillet.

It always did make me mad to git hit over the head with a hot skillet; the grease always gits down the back of yore neck. So I grabbed the cook and went to the floor with him jest in time to duck the charge of buckshot old Jabez blazed at me with the waiter’s shotgun from behind the counter. I then riz up and throwed the cook at him and they both crashed into the wall so hard they brung down all the shelves on it and the cans of beans and milk and corn and stuff fell down on top of Jabez till all I could see was his boots sticking out and his howls was arful to hear.

I was jest on the p’int of throwing the kitchen stove on top of the pile, because I was gitting mad by this time, when a feller hit the porch outside on the run, and stuck his head and a shotgun into the door and hollered, “Halt, in the name of the law!”

“Who the devil air you?” I demanded, rising up amidst a rooin of busted chairs, tables, canned goods and unconscious Watsons.

“I’m the sheriff,” says he. “For the Lord’s sake what’s goin’ on here? You must be one of John McCoy’s men!”

“I’m Pike Bearfield of Wolf Mountain,” I says, and he says, “Well, anyway, yo’re under arrest!”

“If you was a fair-minded officer,” I says, grinding my teeth slightly, “I wouldn’t think of resistin’ arrest. But I can see right off that yo’re in league with the Watsons! This here’s a plot to keep me from aidin’ my pore misguided uncle. I see now why these scoundrels come in here and picked a fight with me. But I’ll foil you, by gum! A Bearfield couldn’t git jestice in yore jailhouse, and I ain’t goin’!”

“You air, too!” he hollered, swinging up his shotgun. But I clapped my hand over the lock between the nipples and the hammers before he could pull the triggers, and I then taken hold of the barrels with my other hand and bent ’em at right angles.

“Now lemme see you try to shoot me with that gun,” I says. “It’ll explode and blow yore fool head off!”

He wept with rage.

“I’ll git even with you, you cussed outlaw!” he promised. “Yore derned uncle has run off and j’ined John McCoy’s bandits, and yo’re one of his spies, I bet! You’ve defied the law and rooint my new shotgun, and I’ll have revenge if I have to sue you in the county court!”

“Gah!” I retorted in disgust, and stalked out in gloomy grandeur, emerging onto the street so sudden-like that the crowd which had gathered outside stampeded in all directions howling bloody murder. I never seen sech skittish folks. You’d of thunk I was a tribe of Comanches.

I headed for the wagon yard, and it was a good thing I got there when I did, because Sinclair’s Defeat had got to fighting with Tom Hanson the yard owner’s saddle pony, and when Tom come out with a pitchfork he bit a chunk outa him and run him into a stall where they was a yoke of oxen. The oxes hooked Tom and every time he crawled out Sinclair’s Defeat kicked him back in again and the oxes taken another swipe at him. You oughta heard him holler.

Well, Sinclair’s Defeat was feeling so brash he thought he could lick me, too, so I give him a good punch on the nose and ontangled Tom from amongst the oxes. He bellyached plumb disgusting about gitting mulebit, so to shet him up I give him my last ten dollar bill. He also wanted me to pay for his britches which the oxes had hooked the seat out of, but I refused profanely and as soon as Sinclair’s Defeat come to, I clumb onto him and headed out along the Choctaw Bayou road.

I hadn’t more’n got outa town when I met a old coot legging it up the road on foot, with his whiskers flying in the wind. As soon as he seen me he hollered, “Whar’s the sheriff ? I got work for him!”

“What kind of work?” I ast, hit by a sudden suspicion.

“Larceny, kidnapin’ and a salt and batter,” says he, stopping to git his breath whilst he fanned hisself with his old broad-brimmed straw hat. “Golly, I’m winded! My farm’s three mile back in the piney woods and I’ve run every step of the way! You know what? While ago I heered a arful racket out to my pigpen and I run out and who should I see but old Joab Hudkins tryin’ to rassle my prize Chester boar, Gen’ral Braddock, over the fence! I sung out: ‘Drap that defenseless animal, you cussed outlaw!’ and I’d no more’n got the words outa my mouth when old Joab up and hit me with a wagon spoke. . . . Looka here!” he displayed a knot on his head about the size of a hen aig. “When I come to,” he says, “Joab was gone and so was Gen’ral Braddock. Sech outrages ain’t to be endured by American citerzens! I’m goin’ after the sheriff!”

“Now wait,” I says. “I dunno what’s the matter with Uncle Joab, but le’s see if we cain’t straighten this out without draggin’ in the law—”

“Don’t speak to me if yo’re kin of his’n!” squalled he, stooping for a rock. “Git outa my way! I’ll have jestice if it’s my last ack!”

“Aw, heck,” I says. “I’ve knowed men to make less fuss over losin’ a thousand head of steers than yo’re makin’ over one measly pig. I’ll see that yo’re paid for yore fool swine.”

He hesitated.

“Show me the dough!” he demanded covetously.

“Well,” I said, “I ain’t got no money right now, but—”

“T’ain’t the money, it’s the principle of the thing!” he asserted. “I ain’t to be tromped on! Stand aside! I’m goin’ for the sheriff.”

“Over my dead carcass!” I roared, losing patience. “Dang yore stubborn old hide! Yo’re comin’ with me till we find Uncle Joab and straighten this thing out—”

I leant down from my saddle and grabbed for him, and he give a squall and hit me in the head with his rock and turnt to run, but he stumped his toe and fell down, and that’s when Sinclair’s Defeat bit him in the seat of the britches. He’s a liar when he says I told Sinclair’s Defeat to bite him; it jest come natural for a mule. I reached down and grabbed him by the galluses—the old coot I mean, and not the mule—and heaved him up acrost the saddle horn in front of me, and he hollered, “Halp! Murder! The McCoy gang got me in the toils!”

Somebody echoed his howl, and I looked around and seen a barefooted kid with a fishing pole in his hand jest coming out of the footpath. His eyes was popping right out of his head.

“Run for the sheriff, boy!” squalled my captive. “Git a posse!”

So the kid scooted for town, howling, “Halp! Halp! A outlaw is kidnapin’ old Ash Buckley!”

Well, I had a suspicion things would be a mite warm around there purty soon, so I kicked Sinclair’s Defeat in the ribs and he done a smart piece of skedaddling up that road. I run for maybe four miles till Ash Buckley’s howls got onbearable. I never seen a human which was harder to please than that old buzzard.

“Set me down and lemme die easy!” he gasped. “This cussed horn has pierced my vitals in front and I have got a mortal wound behind!”

“Aw,” I said, “the mule jest bit off a little piece of hide, not any bigger’n yore hand. You ain’t hurt.”

“I’m dyin’,” he maintained fiercely. “I’ll git even, you big monkey! I’ll come back and ha’nt you, that’s what I’ll do—hey!”

I also give a startled yell, because out of the bresh ambled the most pecooliar looking critter I ever seen in my life. I reached for my pistol, but old Ash give a yowl like he’d been stabbed.

“It’s Gen’ral Braddock!” he shrieked. “They’ve shaved him!”

Then I seen that the critter was a hawg which had wunst been white, but now he was as naked as a newborn babe! They warn’t a bristle onto him; it was plumb ondecent. I was so surprised I let old Ash fall onto the ground, and he jumped up and started for Gen’ral Braddock, saying, “Sooey! Sooey! Come here, boy—”

But Gen’ral Braddock give a squeal and curled his tail and lit a shuck through the bresh.

I jest sat my mule and looked. I couldn’t move.

“He’s plumb upsot,” says old Ash, kinda stunned-like. “Whoever heard of sech doins?” Then he says, “Make room for me on that mule! I aim to find Joab if it takes the rest of my life! Shavin’ a hawg is the craziest thing I ever heard of, and I won’t rest easy till I know why he done it!”

I helped him on behind the saddle, and I says, “Where’ll we look for him? No use tryin’ to backtrack that pig. Neither hoss nor man could git through that thicket he come out of.”

“I figger he’s hidin’ out somewheres over on the Choctaw,” says Ash. “When he tried to steal the Watson hawgs I figgered he’d gone wild and j’ined the outlaws that hang out in the swamps over east of here, and was stealin’ pigs for the McCoys. But he must be jest plain crazy.”

“We’ll head for Uncle Esau Hawkins,” I says, “and round up all the kinfolks and start combin’ the woods. By the way, who is these McCoys?”

“A gang of thieves and cutthroats which used to hang around here,” says he. “They ain’t been seen recent, and I figgers they’ve skipped over into Louisiana. They had a hang-out somewhere in the piney woods and nobody never could find it. They ambushed three or four posses which went in after ’em—What you stoppin’ for?”

We was jest passing a path which crossed the road, and I seen hawg tracks going up it, and a man’s tracks right behind, wide apart.

“Somebody chased a pig up that path right recent,” I says, and turned up it at a lope.

We hadn’t went more’n a mile till we heard a pig squealing. So I slipped off of Sinclair’s Defeat and snuck through the bresh on foot till I come to a little clearing, and there was a white hawg tied up and laying on its side, and there was Uncle Joab Hudkins honing a butcher knife on his boot. A tub of soap suds stood nigh at hand.

“Uncle Joab, air you crazy?” I demanded.

Uncle Joab give a startled yell and fell over backwards into the tub. Sech langwidge you never heard as I hauled him out with soap bubbles in his eyes and ears and mouth. Ash run up jest then.

“That’s Jake Peters’ sow!” he hollered, dancing with excitement. “I tell you, he’s as crazy as a mudhen! You better tie him up!”

“You ontie the hawg,” I says. “I’ll take keer of Uncle Joab.”

“Don’t you ontie that hawg!” howled Uncle Joab. “Gol-dern it, cain’t a man tend to his own business without a passel of idjits buttin’ in?”

“Be calm, Uncle Joab,” I soothed. “I don’t think this’ll be permanent. Yore dad was wunst took like this, they say, and voted agen Sam Houston. But he recovered his sanity before the next election, and you probably will too. Jest when was you first seized with a urge to shave pigs?”

At this Uncle Joab begun to display symptoms of vi’lence, even to the extent of trying to stab me with his butcher knife. But I ignored his rudeness, also his biting me viciously in the hind laig whilst I was setting on him and twisting the knife outa his hand. I was as gentle as I could be with him, but he didn’t have no gratitude, and his langwidge was plumb scandalous to hear.

“I’ve heered a lick on the head will often kyore insanity,” says Ash Buckley. “ ’Twon’t hurt to try, anyhow. You hold him whilst I bust him over the dome with a rock.”

“Don’t you tech me with no rock!” yelled Uncle Joab. “I ain’t crazy, gosh-hang you! I got a good reason for shavin’ them hawgs!”

“Well, why?” I demanded.

“None of yore business,” he sulked.

“All right,” I says with a sigh. “All I see to do is to tie you up and take you over to Uncle Esau Hawkins. He can git a doctor for you, or maybe send you to Austin for observation.”

At that he give a convulsive heave and nearly got loose, but I sot on him and told Ash to go git my lariat off of my saddle.

“Hold on!” says Uncle Joab. “I know when I’m licked. I wanted all the loot for myself, but if you’ll git off of me, I’ll tell you everything.”

“What loot?” I ast.

“The loot Cullen Baker’s gang hid in Choctaw Bayou,” says he.

Old Ash pricked up his ears at that.

“You mean to say yo’re on the trail of that?” he demanded.

“I am!” asserted Uncle Joab. “Listen! We all know that a few months before Baker was kilt, he robbed a train jest over the Louisiana line. He then come over here and hid the gold—a hundred thousand dollars’ wuth!—somewhar on Choctaw. Nobody knows whar, because right after that him and all the men which was with him when he hid it, got kilt over night. Jefferson, in 1869. They paid ten thousand dollars for his head in Little Rock.

“Well, I been lookin’ for that plunder off and on for years, like everybody else around here, especially old Jeppard Wilkinson, which used to hold a grudge agen me account of me skinnin’ him in a mule swap. But I got a letter from him the other day, from New Orleans, and he said he’d had a change of heart. He said before he left here he found where Baker’s treasure was hid! But he was afeared to take it out, account of the McCoy gang which was huntin’ it too, and always follerin’ him around and spyin’ on him, so he drawed a map of the place and was waitin’ a chance to go back and git the loot, when he got run out of the country—you know, Ash, on account of the trouble he had with the Clantons—and now he says he wasn’t never comin’ back, so if I could find the map the loot would be mine. And he said he tattooed the map on a white hawg! He said he reckon it run off into the woods after he left the country.”

“Well, whyn’t you tell us all this in the first place?” yelled old Ash. “What air we waitin’ on? Pike, you hold this critter whilst me and Joab scrapes the bristles off. This may be the very hawg.”

Well, I felt plumb silly helping shave a pig, but them old coots was serious. They like to have fit right in the middle of the job when they got to argying how they’d divide the plunder. I told ’em they better wait till they found it before they divided it.

Well, they shaved that critter from stem to stern, but not one mark did they find that looked like a map. But they warn’t discouraged.

“I’ve shaved six already,” says Uncle Joab. “I aim to find that map if I have to shave every white hawg in the county. They ain’t none been butchered since old Jeppard tattooed that’n, so it’s bound to be somewheres in these woods. Listen: I been livin’ in the old Sorley cabin over on the Choctaw. You all go over there with me, and we’ll take up our camp there and work out from it. They ain’t no settlements within a long ways of it, and all the pigs in the county comes over there to that oak grove about a mile from it to eat acorns. Won’t be nobody to interfere with us, and we’ll stay there and comb the woods till we finds the right hawg.”

So we pulled out, taking turns riding and walking.

We went through mighty wild, tangled, uninhabited country to git to that there cabin, which stood a few hundred yards from the bank of the Choctaw. Mostly we follered pig trails through the thickets. On the way Uncle Joab told us the McCoys used to hang out in them parts, and he bet they’d show up again sometime when Louisiana got too hot for ’em, and start burning cabins and stealing and shooting folks from the bresh again. And Ash Buckley said he bet the sheriff of Sabineville wouldn’t never catch ’em, and they got to talking about all the crimes them McCoys had committed, and I was plumb surprised to hear white men could ack like that. They was wuss’n Apaches. They shore wouldn’t of lasted long on Wolf Mountain.

Well, we slept at the cabin that night and early next morning we scattered through the pine flats and cypress swamps looking for white hawgs. Uncle Joab told me not to git lost nor et up by a alligator. Shucks, you could lose a timber wolf as easy as a Bearfield, even in the piney woods, and the muskeeters worrit me more’n the alligators.

I didn’t have no luck looking for white pigs. All I found was plain razorbacks. I finally got disgusted pulling through them swamps and thickets on foot, so about noontime I headed back for the cabin. And when I come out in the clearing I seen a man in the rail pen behind the cabin trying to rope Sinclair’s Defeat. I hollered at him and he ducked and pulled a pistol out of his boot and taken a shot at me, and then ran off into the bresh.

Well, I instantly knowed it was one of them dern Watsons trying to run off our stock and set us afoot so they could snipe us off at their leisure, so I taken in after him. They must of tracked us from Sabineville.

He knowed the country better’n I did, and he stayed ahead of me for three miles, heading south, but he couldn’t shake me off, because us Bearfields learnt tracking from the Yaquis. I gained on him and warn’t but a few yards behind him when he come into a clearing in the middle of the dangedest thicket I ever seen. A path had been cut through it with axes, but if I hadn’t been follering his tracks I probably wouldn’t never have found it, the mouth was so well hid, and not even a razorback could git through anywheres else.

I taken a shot at him as he broke cover and legged it for a cabin in the clearing, and then I started after him; but three or four men opened up on me from the door with Winchesters, so I jumped back into the bresh. He ducked inside and they slammed the door.

It was a hundred yards from the bresh to the cabin, and no cover for a man to crawl up clost. They’d riddle him if he tried it. There warn’t no winders, jest loopholes to shoot through, and the door looked arful thick. Leastways when I tried to shoot through it with my pistol the men inside hollered jeeringly and shot at me through the loopholes. The cabin was built up agen a big rock, the first of its size I’d saw in that country, so they warn’t no chance of storming ’em from the rear. It looked like they jest warn’t no way of coming to grips with them devils.

Then I seen smoke coming out of the top of the rock, and I knowed they had a fireplace built into the rock which formed the back wall of the cabin, and had tunneled out a chimney in the rock. I thought by golly, I bet if I was to climb up onto that rock from behind and drop a polecat down that chimney I could shoot all them Watsons as they run out.

So I fired a few shots at the door, and then ducked low and snuck off. I figgered they’d stay denned up till dark at least, thinking I was still laying for ’em outside, and by that time I could find me a skunk and git back with it. I was depending a lot on it. I notice the average man would rather run the risk of gitting shot than to stay denned up in a winderless cabin with a irritated polecat.

But I looked and looked, and didn’t find none, and it begun to git late, and all at once I thought by golly, I bet a alligator would have the same effect. The nearest way to the bayou was back by our cabin, so I headed that way.

The cabin was empty when I went past it. Uncle Joab and Ash Buckley was still out looking for the tattooed hawg. I went on to the Bayou where I’d heard a big bull beller the night before, and waded out in the water to find him, which I presently did by him grabbing me by the hind laig. So I waded to shore with him, him being too stubborn to let go, and suffering from the illusion that he could pull me out into deep water.

Ain’t it funny what fools some animals is? It’s ideas like that proves their undoing.

When he realized his error we was already in the shallers, so I pried him loose and got him under my arm and started for the bank with him. He then started swinging his tail up and hitting me in the back of the head with it, and it was wuss’n being kicked by a mule. He knocked me down three times before I got out of the water, and nearly wiggled away from me each time, to say nothing of biting me severely in various places. They is nothing more stubborn than a old bull alligator.

Finally I got so disgusted with him I hauled off with my fist and busted him betwixt the eyes, and whilst he was stunned I broke some vines and tied his laigs, and then I could carry him better. I called him Jedge Peabody because he looked so much like a jedge back in my country which would of fined me for shooting Jack Rackston wunst, only I wouldn’t stand for no sech interference with my personal liberty.

Well, I couldn’t figger out no way to tie Jedge Peabody’s tail, and he come to purty soon and started beating me in the neck with it again. It was gitting arful late by now, and I was afeared the Watsons would come out of their cabin and find me gone. So I decided to stop off at our cabin and then ride back instead of going afoot. I figgered to have some trouble with Sinclair’s Defeat when I put Jedge Peabody on his back, but I ’lowed I could persuade him.

So I taken Jedge Peabody up to our cabin and laid him on my bunk to keep him safe till I saddled up. The sun was already outa sight behind the pines and the long shadders was streaming acrost the clearing. It was purty dark in the cabin and you could hardly see Jedge Peabody at all.

Well, I went to the hoss pen and grabbed my saddle, but before I could throw it on, I seen Uncle Joab cross the clearing from the east and go into the cabin. I started to call to him, but the next instant he give a arful screech and come busting out of there so fast he tripped and slid on his nose for about three yards.

“Halp! Murder! The Devil hisself ’s in that cabin!” he screamed, and bounced up and streaked for the tall timber.

“Uncle Joab, come back!” I yelled, jumping the pen fence and lighting out after him. “That ain’t nobody but Jedge Peabody!”

But he jest yelled that much louder and put on more speed. I reckon Jedge Peabody did look kind of uncanny to come onto him unexpected in that dark corner where you couldn’t see much but his big red eyes. Uncle Joab didn’t even look back, and when he heard me crashing through the bresh right behind him, he evidently thought the devil was chasing him, because he let out some more arful screams and jest went a-kiting.

It was dark under the trees, and I reckon that’s why he didn’t see that gully in front of him, anyway, he suddenly vanished from sight with a crash and a howl. Then they busted out an arful squealing and out of the gully come the biggest white hawg I ever seen in my life. And Uncle Joab was astraddle of him, having evidently fell on him.

“Stop him!” howled Uncle Joab, hanging on for his life, afeared to let go and afeared to hold on. That hawg was headed back the way we’d come, and he went past me like a bullet. I grabbed for him, but all I done was tear off Uncle Joab’s shirt. That hawg went through the bresh like a quarter hoss, and the way Uncle Joab hollered was a caution when the limbs scratched him and slapped him in the face.

Well, a Bearfield ain’t to be outdid by man nor beast, so I sot myself to run down that fool hawg on foot. And I was gaining on him, too, when we reached the cabin. But as we busted into the clearing I heard a most amazing racket in the cabin and seen Ash Buckley perched in a tree, plumb wildeyed.

I was so astonished I didn’t look where I was going and tripped over a root and nearly busted my brains out, and when I got up, Uncle Joab and the hawg was clean out of sight.

“What the devil?” I demanded profanely.

“I dunno!” hollered old Ash. “Jest as I come up awhile ago I seen a gang of men sneakin’ into the cabin, so I hid and watched. They shet the door and I heard one of ’em holler: ‘That must be him layin’ on that bunk over there. Grab him!’ Then that racket started. It’s been goin’ on for fifteen minutes. What’s that?”

It sounded like a mule kicking slats out of a shed wall, but I knowed it was Jedge Peabody hitting the Watsons in the head with his tail. Them scoundrels had evidently come to raid our cabin, and Jedge Peabody had busted loose when they grabbed him, thinking he was me.

I run over to the door jest as it was busted down from inside, and a gang of men come piling out. I hit each one on the jaw as he come out, and throwed him to one side till I had seven men laying there, out cold. The last one to come out had Jedge Peabody hanging onto the seat of his britches, and when old Ash seen Jedge Peabody he give a shriek and fell outa the tree and would probably of broke his neck if his galluses hadn’t catched on a limb.

The last Watson I knocked stiff had a scarred face and was about the meanest-looking cuss I ever seen. He was tough, too. I had to hit him twice. I was expecting a tussle with Jedge Peabody, too, but as soon as he seen me he let go of his victim’s pants and scuttled for the creek as fast as he could go. I never seen a ’gator run like him.

Ash was yelling for me to help him down, but they was more important work to do, so I run and got my lariat and tied them Watsons up before they could come to and rolled ’em into the cabin. Then I started towards the tree to git Ash loose, when somebody says, “Hands up!” and whirled around and faced the sheriff and fifty men, all of which was aiming shotguns at me.

“Don’t move!” says the sheriff, which was weighted down with hand-cuffs and laig-irons and chains till he couldn’t hardly walk. “We got you kivered, Bearfield! Them guns is all loaded with buckshot and railroad spikes! We got you cold! Where’s Ash Buckley?”

“Right up over yore fool heads,” says Ash fiercely, which startled the posse so bad they nigh jumped outa their skins and four or five of ’em shot at him before they seen who it was. “Stop that, you nitwits!” he screamed. “Lemme down before I has a rush of blood to the head!”

“Warn’t you kidnaped?” ast the sheriff, dumbfounded, and Ash snarled, “No, I warn’t! Me and Pike and Joab come out here on private business!”

The sheriff cussed something fierce, but the posse started helping Ash down, when we heard somebody hollering for help off to the west, and they dropped Ash on his head and grabbed their guns and says, “Who’s that?”

“It’s Uncle Joab!” I bellered, and made a break for the bresh, with Ash right behind me. Some of ’em shot at me, but they missed, and jest then I heard one of ’em yell, “Sheriff, come here quick! The cabin’s full of men tied hand and foot!”

Every second I expected to hear ’em pursuing us, but we didn’t hear ’em, and purty soon we almost fell over Uncle Joab in the dusk. He was trying to rassle the white hawg over on its side, whilst squalling, “It’s the one! I can see the tattoo marks through the bristles!”

Well, so could we, in spite of the dusk, and old Ash like to collapsed with excitement.

“Grab that hawg, Pike!” he screamed, lugging out a handful of matches. “Cullen Baker’s loot is right in our meat hooks!”

So I helt the hawg and Uncle Joab made a swipe with his butcher knife, and panted, “Strike a match quick, Ash! ’Tain’t a map—it’s writin’, but I cain’t read it by this light! Strike a light!”

Ash struck a match and helt it clost whilst we jammed our three heads together to read what was tattooed on that hawg’s hide. And then Ash and Uncle Joab give a howl that jolted the cones outa the pines. The words tattooed on that hawg was, “April fule! The joaks on you, you old jackass. jeppard wilkinson.”

I let go of the hawg and it went kiting and squealing off into the bresh, and we sot there in bitter silence for a long time.

This silence was busted by the sheriff suddenly sticking his head through the bushes, and saying, “What the devil air you all doin’?”

“Well, I ain’t bein’ arrested,” I says vengefully, gitting to my feet and drawing my pistol. “I’ll pay you for yore shotgun, but—”

“Then I got no charge,” says he. “Bein’ as you didn’t kidnap Ash there, and as for the Watsons—”

“That reminds me,” I interrupted. “I got seven of them skunks tied up back at the cabin. They tried to steal my mule and murder me in my sleep, but I won’t make no charges agen ’em if they’ll drop that pig stealin’ case.”

“Why, heck!” says he. “They’ve already dropped that charge! When old Jabez come to he ’lowed all he wanted with yore clan was peace, and plenty of it! He says they can lick the Hudkinses any day, but when they rings in a Bearfield on ’em, they got more’n enough! Them fellers you got tied up back there—and which the boys is now loadin’ with the irons I brung for you—they ain’t Watsons!”

“Well, who is they, then?”

“Oh,” says he, taking a chaw of plug tobaccer, “nobody but John McCoy and his gang which recent come back from Louisiana! Son, you can have anything in this county! Hey, where you goin’?”

“Home,” I says in disgust, “where a man can depend on a feud bein’ fought to a finish, and one side don’t back out jest because a few of ’em gits their heads busted!”