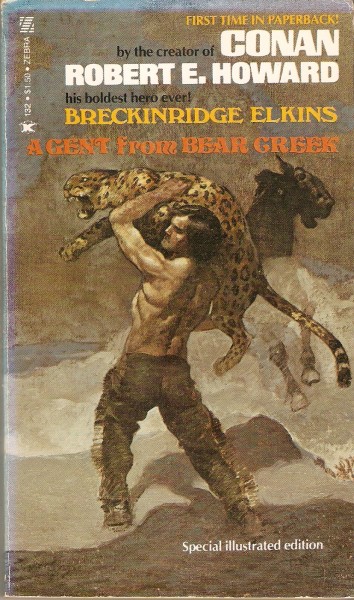

Cover from the Zebra Books edition (1975).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in A Gent from Bear Creek, Jenkins (1937).

| Chapter I - Striped Shirts and Busted Hearts Chapter II - Mountain Man Chapter III - Meet Cap’n Kidd Chapter IV - Guns of the Mountains Chapter V - A Gent from Bear Creek Chapter VI - The Feud Buster Chapter VII - The Road to Bear Creek |

Chapter VIII - The Scalp Hunter Chapter IX - Cupid from Bear Creek Chapter X - The Haunted Mountain Chapter XI - Educate or Bust Chapter XII - War on Bear Creek Chapter XIII - When Bear Creek Came to Chawed Ear |

If Joel Braxton hadn’t drawed a knife whilst I was beating his head agen a spruce log, I reckon I wouldn’t of had that quarrel with Glory McGraw, and things might of turned out different to what they did. Pap’s always said the Braxtons was no-account folks, and I allow he’s right. First thing I knowed Jim Garfield hollered: “Look out, Breck, the yaller hound’s got a knife!” Then I felt a kind of sting and looked down and seen Joel had cut a big gash in my buckskin shirt and scratched my hide trying to get at my innards.

I let go of his ears and taken the knife away from him and throwed it into a blackjack thicket, and throwed him after it. They warn’t no use in him belly-aching like he done just because they happened to be a tree in his way. I dunno how he expects to get throwed into a blackjack thicket without getting some hide knocked off.

But I am a good-natured man, and I was a easy-going youngster, even then. I paid no heed to Joel’s bloodthirsty threats whilst his brother and Jim Garfield and the others was pulling him out of the bresh and dousing him in the creek to wash the blood off. I got on to my mule Alexander and headed for Old Man McGraw’s cabin where I was started to when I let myself be beguiled into stopping with them idjits.

The McGraws is the only folks on Bear Creek besides the Reynoldses and the Braxtons which ain’t no kin to me one way or another, and I’d been sweet on Glory McGraw ever since I was big enough to wear britches. She was the tallest, finest, purtiest gal in the Humbolt Mountains, which is covering considerable territory. They warn’t a gal on Bear Creek, not even my own sisters, which could swing a axe like her, or fry a b’ar steak as tasty, or make hominy as good, and they warn’t nobody, man nor woman, which could outrun her, less’n it was me.

As I come up the trail that led up to the McGraw cabin, I seen her, just scooping a pail of water out of the creek. The cabin was just out of sight on the other side of a clump of alders. She turned around and seen me, and stood there with the pail dripping in her hand, and her sleeves rolled up, and her arms and throat and bare feet was as white as anything you ever seen, and her eyes was the same color as the sky, and her hair looked like gold dust when the sun hit it.

I taken off my coonskin cap, and said: “Good mornin’, Glory, how’re you-all this mornin’?”

“Joe got kicked right severe by pap’s sorrel mare yesterday,” she says. “Just knocked some hide off, though. Outside of that we’re all doin’ fine. Air you glued to that mule?”

“No’m,” I says, and clumb down, and says: “Lemme tote yore pail, Glory.”

She started to hand it to me, and then she frowned and p’inted at my shirt, and says: “You been fightin’ agen.”

“Nobody but Joel Braxton,” I said. “ ’Twarn’t nothin’. He said moskeeters in the Injun Territory was bigger’n what they be in Texas.”

“What you know about it?” says she. “You ain’t never been to Texas.”

“Well, he ain’t never been to the Injun Territory neither,” I said. “ ’Taint the moskeeters. It’s the principle of the thing. My folks all come from Texas, and no Braxton can slander the State around me.”

“You fight too much,” she said. “Who licked?”

“Why, me, of course,” I said. “I always do, don’t I?”

This harmless statement seemed to irritate her.

“I reckon you think nobody on Bear Creek can lick you,” she sneered.

“Well,” I says truthfully, “nobody ain’t, up to now—outside of pap.”

“You ain’t never fit none of my brothers,” she snapped.

“That’s why,” I said. “I’ve took quite a lot of sass offa them ganglin’ mavericks jest because they was yore brothers and I didn’t want to hurt ’em.”

Gals is funny about some things. She got mad and jerked the pail out of my hand, and says: “Oh, is that so? Well, lemme tell you right now, Breckinridge Elkins, the littlest one of my brothers can lick you like a balky hoss, and if you ever lay a finger on one of ’em, I’ll fix you! And furthermore and besides, they’s a gent up to the cabin right now which could pull his shootin’ iron and decorate yore whole carcass with lead polka-dots whilst you was fumblin’ for yore old cap-and-ball pistol!”

“I don’t claim to be no gunfighter,” I says mildly. “But I bet he cain’t sling iron fast as my cousin Jack Gordon.”

“You and yore cousins!” says she plenty scornful. “This feller is sech a gent as you never drempt existed! He’s a cowpuncher from the Wild River Country, and he’s ridin’ through to Chawed Ear and he stopped at our cabin for dinner. If you could see him, you wouldn’t never brag no more. You with that old mule and them moccasins and buckskin clothes!”

“Well, gosh, Glory!” I says plumb bewildered. “What’s the matter with buckskin? I like it better’n homespun.”

“Hah!” sneered she. “You oughta see Mr. Snake River Wilkinson! He ain’t wearin’ neither buckskins nor homespun. Store-bought clothes! I never seen such elegance. Star top boots, and gold-mounted spurs! And a red neckcloth—he said silk. I dunno. I never seen nothin’ like it before. And a shirt all red and green and yaller and beautiful! And a white Stetson hat! And a pearl-handled six-shooter! And the finest hoss and riggin’s you ever seen, you big dummox!”

“Aw, well, gosh!” I said, getting irritated. “If this here Mister Wilkinson is so blame gorgeous, whyn’t you marry him?”

I ought not to said it. Her eyes flashed blue sparks.

“I will!” she gritted. “You think a fine gentleman like him wouldn’t marry me, hey? I’ll show you! I’ll marry him right now!”

And impulsively shattering her water bucket over my head she turned and run up the trail.

“Glory, wait!” I hollered, but by the time I got the water out of my eyes and the oak splinters out of my hair she was gone.

Alexander was gone too. He taken off down the creek when Glory started yelling at me, because he was a smart mule in his dumb way, and could tell when thunder-showers was brewing. I run him for a mile before I caught him, and then I got onto him and headed for the McGraw cabin agen. Glory was mad enough to do anything she thought would worry me, and they warn’t nothing would worry me more’n for her to marry some dern cowpuncher from the river country. She was plumb wrong when she thought I thought he wouldn’t have her. Any man which would pass up a chance to get hitched with Glory McGraw would be a dern fool, I don’t care what color his shirt was.

My heart sunk into my moccasins as I approached the alder clump where we’d had our row. I figgered she’d stretched things a little talking about Mr. Wilkinson’s elegance, because whoever heard of a shirt with three colors into it, or gold-mounted spurs? Still, he was bound to be rich and wonderful from what she said, and what chance did I have? All the clothes I had was what I had on, and I hadn’t never even seen a store-bought shirt, much less owned one. I didn’t know whether to fall down in the trail and have a good bawl, or go get my rifle-gun and lay for Mr. Wilkinson.

Then, jest as I got back to where I’d saw Glory last, here she come again, running like a scairt deer, with her eyes all wide and her mouth open.

“Breckinridge!” she panted. “Oh, Breckinridge! I’ve played hell now!”

“What you mean?” I said.

“Well,” says she, “that there cowpuncher Mister Wilkinson had been castin’ eyes at me ever since he arriv at our cabin, but I hadn’t give him no encouragement. But you made me so mad awhile ago, I went back to the cabin, and I marched right up to him, and I says: ‘Mister Wilkinson, did you ever think about gittin’ married?’ He grabbed me by the hand and he says, says he: ‘Gal, I been thinkin’ about it ever since I seen you choppin’ wood outside the cabin as I rode by. Fact is, that’s why I stopped here.’ I was so plumb flabbergasted I didn’t know what to say, and the first thing I knowed, him and pap was makin’ arrangements for the weddin’!”

“Aw, gosh!” I said.

She started wringing her hands.

“I don’t want to marry Mister Wilkinson!” she hollered. “I don’t love him! He turnt my head with his elegant manners and striped shirt! What’ll I do? Pap’s sot on me marryin’ the feller!”

“Well, I’ll put a stop to that,” I says. “No dern cowcountry dude can come into the Humbolts and steal my gal. Air they all up to the cabin now?”

“They’re arguin’ about the weddin’ gift,” says Glory. “Pap thinks Mister Wilkinson oughta give him a hundred dollars. Mister Wilkinson offered him his Winchester instead of the cash. Be keerful, Breckinridge! Pap don’t like you much, and Mister Wilkinson has got a awful mean eye, and his scabbard-end tied to his laig.”

“I’ll be plumb diplomatic,” I promised, and got onto my mule Alexander and reched down and lifted Glory on behind me, and we rode up the path till we come to within maybe a hundred foot of the cabin door. I seen a fine white hoss tied in front of the cabin, and the saddle and bridle was the most elegant I ever seen. The silverwork shone when the sun hit it. We got off and I tied Alexander, and Glory hid behind a white oak. She warn’t scairt of nobody but her old man, but he shore had her number.

“Be keerful, Breckinridge,” she begged. “Don’t make pap or Mister Wilkinson mad. Be tactful and meek.”

So I said I would, and went up to the door. I could hear Miz McGraw and the other gals cooking dinner in the back room, and I could hear Old Man McGraw talking loud in the front room.

“ ’Taint enough!” says he. “I oughta have the Winchester and ten dollars. I tell you, Wilkinson, it’s cheap enough for a gal like Glory! It plumb busts my heart strings to let her go, and nothin’ but greenbacks is goin’ to soothe the sting!”

“The Winchester and five bucks,” says a hard voice which I reckoned was Mister Wilkinson. “It’s a prime gun, I tell you. Ain’t another’n like it in these mountains.”

“Well,” begun Old Man McGraw in a covetous voice, and jest then I come in through the door, ducking my head to keep from knocking it agen the lintel-log.

Old Man McGraw was setting there, tugging at his black beard, and them long gangling boys of his’n, Joe and Bill and John, was there gawking as usual, and there on a bench nigh the empty fireplace sot Mister Wilkinson in all his glory. I batted my eyes. I never seen such splendor in all my born days. Glory had told the truth about everything: the white Stetson with the fancy leather band, and the boots and gold-mounted spurs, and the shirt. The shirt nigh knocked my eyes out. I hadn’t never dreamed nothing could be so beautiful—all big broad stripes of red and yaller and green! I seen his gun, too, a pearl-handled Colt .45 in a black leather scabbard which was wore plumb smooth and the end tied down to his laig with a rawhide thong. I could tell he hadn’t never wore a glove on his right hand, neither, by the brownness of it. He had the hardest, blackest eyes I ever seen. They looked right through me.

I was very embarrassed, being quite young then, but I pulled myself together and says very polite: “Howdy, Mister McGraw.”

“Who’s this young grizzly?” demanded Mister Wilkinson suspiciously.

“Git out of here, Elkins,” requested Old Man McGraw angrily. “We’re talkin’ over private business. You git!”

“I know what kind of business you-all are talkin’ over,” I retorted, getting irritated. But I remembered Glory said be diplomatic, so I said: “I come here to tell you the weddin’s off! Glory ain’t goin’ to marry Mister Wilkinson. She’s goin’ to marry me, and anybody which comes between us had better be able to rassle cougars and whup grizzlies bare-handed!”

“Why, you—” begun Mister Wilkinson in a blood-thirsty voice, as he riz onto his feet like a painter fixing to go into action.

“Git outa here!” bellered Old Man McGraw jumping up and grabbing the iron poker. “What I does with my datter ain’t none of yore business! Mister Wilkinson here is makin’ me a present of his prime Winchester and five dollars in hard money! What could you offer me, you mountain of beef and ignorance?”

“A bust in the snoot, you old tightwad,” I replied heatedly, but still remembering to be diplomatic. They warn’t no use in offending him, and I was determined to talk quiet and tranquil, in spite of his insults. So I said: “A man which would sell his datter for five dollars and a gun ought to be et alive by the buzzards! You try to marry Glory to Mister Wilkinson and see what happens to you, sudden and onpleasant!”

“Why, you—!” says Old Man McGraw, swinging up his poker. “I’ll bust yore fool skull like a egg!”

“Lemme handle him,” snarled Mister Wilkinson. “Git outa the way and gimme a clean shot at him. Lissen here, you jack-eared mountain-mule, air you goin’ out of here perpendicular, or does you prefer to go horizontal?”

“Open the ball whenever you feels lucky, you stripe-bellied polecat!” I retorted courteously, and he give a snarl and went for his gun, but I got mine out first and shot it out of his hand along with one of his fingers before he could pull his trigger.

He give a howl and staggered back agen the wall, glaring wildly at me, and at the blood dripping off his hand, and I stuck my old cap-and-ball .44 back in the scabbard and said: “You may be accounted a fast gunslinger down in the low country, but yo’re tolerable slow on the draw to be foolin’ around Bear Creek. You better go on home now, and—”

It was at this moment that Old Man McGraw hit me over the head with his poker. He swung it with both hands as hard as he could, and if I hadn’t had on my coonskin cap I bet it would have skint my head some. As it was it knocked me to my knees, me being off-guard that way, and his three boys run in and started beating me with chairs and benches and a table laig. Well, I didn’t want to hurt none of Glory’s kin, but I had bit my tongue when the old man hit me with his poker, and that always did irritate me. Anyway, I seen they warn’t no use arguing with them fool boys. They was out for blood—mine, to be exact.

So I riz up and taken Joe by the neck and crotch and throwed him through a winder as gentle as I could, but I forgot about the hickory-wood bars which was nailed acrost it to keep the bears out. He took ’em along with him, and that was how he got skint up like he did. I heard Glory let out a scream outside, and would have hollered out to let her know I was all right and for her not to worry about me, but just as I opened my mouth to do it, John jammed the butt-end of a table laig into it.

Sech treatment would try the patience of a saint, still and all I didn’t really intend to hit John as hard as I did. How was I to know a tap like I give him would knock him through the door and dislocate his jawbone?

Old Man McGraw was dancing around trying to get another whack at me with his bent poker without hitting Bill which was hammering me over the head with a chair, but Mister Wilkinson warn’t taking no part in the fray. He was backed up agen a wall with a wild look on his face. I reckon he warn’t used to Bear Creek squabbles.

I taken the chair away from Bill and busted it over his head jest to kinda cool him off a little, and jest then Old Man McGraw made another swipe at me with his poker, but I ducked and grabbed him, and Bill stooped over to pick up a bowie knife which had fell out of somebody’s boot. His back was towards me so I planted my moccasin in the seat of his britches with considerable force and he shot head-first through the door with a despairing howl. Somebody else screamed too, that sounded like Glory. I didn’t know at the time I that she was running up to the door and was knocked down by Bill as he catapulted into the yard.

I couldn’t see what was going on outside, and Old Man McGraw was chawing my thumb and feeling for my eye, so I throwed him after John and Bill, and he’s a liar when he said I aimed him at that rain-barrel a-purpose. I didn’t even know they was one there till I heard the crash as his head went through the staves.

I turned around to have some more words with Mister Wilkinson, but he jumped through the winder I’d throwed Joe through, and when I tried to foller him, I couldn’t get my shoulders through. So I run out at the door and Glory met me just as I hit the yard and she give me a slap in the face that sounded like a beaver hitting a mud bank with his tail.

“Why, Glory!” I says, dumbfounded, because her blue eyes was blazing, and her yaller hair was nigh standing on end. She was so mad she was crying and that’s the first time I ever knowed she could cry. “What’s the matter? What’ve I did?”

“What have you did?” she raged, doing a kind of a war-dance on her bare feet. “You outlaw! You murderer! You jack-eared son of a spotted tail skunk! Look what you done!” She p’inted at her old man dazedly pulling his head out of the rooins of the rain-barrel, and her brothers laying around the yard in various positions, bleeding freely and groaning loudly. “You tried to murder my family!” says she, shaking her fists under my nose. “You throwed Bill onto me on purpose!”

“I didn’t neither!” I exclaimed, shocked and scandalized. “You know I wouldn’t hurt a hair of yore head, Glory! Why, all I done, I done it for you—”

“You didn’t have to mutilate my pap and my brothers!” she wept furiously. Ain’t that just like a gal? What could I done but what I did? She hollered: “If you really loved me you wouldn’t of hurt ’em! You jest done it for meanness! I told you to be ca’m and gentle! Whyn’t you do it? Shet up! Don’t talk to me! Well, whyn’t you say somethin’? Ain’t you got no tongue?”

“I handled ’em easy as I could!” I roared, badgered beyond endurance. “It warn’t my fault. If they’d had any sense, they wouldn’t—”

“Don’t you dare slander my folks!” she yelped. “What you done to Mister Wilkinson?”

The aforesaid gent jest then come limping around the corner of the cabin, and started for his hoss, and Glory run to him and grabbed his arm, and said: “If you still want to marry me, stranger, it’s a go! I’ll ride off with you right now!”

He looked at me and shuddered, and jerked his arm away.

“Do I look like a dern fool?” he inquired with some heat. “I advises you to marry that young grizzly there, for the sake of public safety, if nothin’ else! Marry you when he wants you? No, thank you! I’m leavin’ a valuable finger as a sooverneer of my sojourn, but I figger it’s a cheap price! After watchin’ that human tornado in action, I calculate a finger ain’t nothin’ to bother about! Adios! If I ever come within a hundred miles of Bear Creek again it’ll be because I’ve gone plumb loco!”

And with that he forked his critter and took off up the trail like the devil was after him.

“Now look what you done!” wept Glory. “Now he won’t never marry me!”

“But I thought you didn’t want to marry him!” I says, plumb bewildered.

She turned on me like a catamount.

“I didn’t!” she shrieked. “I wouldn’t marry him if he was the last man on earth! But I demands the right to say yes or no for myself! I don’t aim to be bossed around by no hillbilly on a mangy mule!”

“Alexander ain’t mangy,” I said. “Besides, I warn’t, tryin’ to boss you around, Glory. I war just fixin’ it so yore pap wouldn’t make you marry Mister Wilkinson. Bein’ as we aims to marry ourselves—”

“Who said we aimed to?” she hollered. “Me marry you, after you beat up my pap and my brothers like you done? You think yo’re the best man on Bear Creek! Ha! You with yore buckskin britches and old cap-and-ball pistol and coonskin cap! Me marry you? Git on yore mangy mule and git before I takes a shotgun to you!”

“All right!” I roared, getting mad at last. “All right, if that’s the way you want to ack! You ain’t the only gal in these mountains! They’s plenty of gals which would be glad to have me callin’ on ’em.”

“Who, for a instance?” she sneered.

“Ellen Reynolds, for instance!” I bellered. “That’s who!”

“All right!” says she, trembling with rage. “Go and spark that stuck-up hussy on yore mangy mule with yore old moccasins and cap-and-ball gun! See if I care!”

“I aim to!” I assured her bitterly. “And I won’t be on no mule, neither. I’ll be on the best hoss in the Humbolts, and I’ll have me some boots on to my feet, and a silver mounted saddle and bridle, and a pistol that shoots store-bought ca’tridges, too! You wait and see!”

“Where you think you’ll git ’em?” she sneered.

“Well, I will!” I bellered, seeing red. “You said I thought I was the best man on Bear Creek! Well, by golly, I am, and I aim to prove it! I’m glad you gimme the gate! If you hadn’t I’d of married you and settled down in a cabin up the creek somewheres and never done nothin’ nor seen nothin’ nor been nothin’ but yore husband! Now I’m goin’ to plumb bust this State wide open from one end to the other’n, and folks is goin’ to know about me all over everywheres!”

“Heh! heh! heh!” she laughed bitterly.

“I’ll show you!” I promised her wrathfully, as I forked my mule, and headed down the trail with her laughter ringing in my ears. I kicked Alexander most vicious in the ribs, and he give a bray of astonishment and lit a shuck for home. A instant later the alder clump hid the McGraw cabin from view and Glory McGraw and my boyhood dreams was out of sight behind me.

“I’ll show her!” I promised the world at large, as I rode through the bresh as hard as Alexander could run. “I’ll go out into the world and make a name for myself, by golly! She’ll see. Whoa, Alexander!”

Because I’d jest seen a bee-tree I’d located the day before. My busted heart needed something to soothe it, and I figgered fame and fortune could wait a little whilst I drowned my woes in honey.

I was up to my ears in this beverage when I heard my old man calling: “Breckinridge! Oh, Breckinridge! Whar air you? I see you now. You don’t need to climb that tree. I ain’t goin’ to larrup you.”

He come up and said: “Breckinridge, ain’t that a bee settin’ on to yore ear?”

I reched up, and sure enough, it was. Come to think about it, I had felt kind of like something was stinging me somewheres.

“I swar, Breckinridge,” says pap, “I never seen a hide like yore’n not even amongst the Elkinses. Lissen to me now: old Buffalo Rogers jest come through on his way back from Tomahawk, and the postmaster there said they was a letter for me, from Mississippi. He wouldn’t give it to nobody but me or some of my folks. I dunno who’d be writin’ me from Mississippi; last time I was there was when I was fightin’ the Yankees. But anyway, that letter is got to be got. Me and yore maw have decided yo’re to go git it.”

“Clean to Tomahawk?” I said. “Gee whiz, Pap!”

“Well,” he says, combing his beard with his fingers, “yo’re growed in size, if not in years. It’s time you seen somethin’ of the world. You ain’t never been more’n thirty miles away from the cabin you was born in. Yore brother Garfield ain’t able to go on account of that b’ar he tangled with, and Buckner is busy skinnin’ the b’ar. You been to whar the trail goin’ to Tomahawk passes. All you got to do is foller it and turn to the right whar it forks. The left goes on to Perdition.”

“Great!” I says. “This is whar I begins to see the world!” And I added to myself: “This is whar I begins to show Glory McGraw I’m a man of importance, by golly!”

Well, next morning before good daylight I was off, riding my mule Alexander, with a dollar pap gimme stuck in the bottom of my pistol scabbard. Pap rode with me a few miles and give me advice.

“Be keerful how you spend that dollar I give you,” he said. “Don’t gamble. Drink in reason. Half a gallon of corn juice is enough for any man. Don’t be techy—but don’t forgit that yore pap was once the rough-and-tumble champeen of Gonzales County, Texas. And whilst yo’re feelin’ for the other feller’s eye, don’t be keerless and let him chaw yore ear off. And don’t resist no officer.”

“What’s them, Pap?” I inquired.

“Down in the settlements,” he explained, “they has men which their job is to keep the peace. I don’t take no stock in law myself, but them city folks is different from us. You do what they says, and if they says give up yore gun, even, why you up and do it!”

I was shocked, and meditated a while, and then says: “How can I tell which is them?”

“They’ll have a silver star stuck onto their shirt,” he says, so I said I’d do like he told me. He then reined around and went back up the mountains, and I rode on down the path.

Well, I camped late that night where the path come out onto the Tomahawk trail, and the next morning I rode on down the trail, feeling like I was a long way from home. It was purty hot, and I hadn’t went far till I passed a stream and decided I’d take a swim. So I tied Alexander to a cottonwood, and hung my buckskins close by, but I taken my gun belt with my cap-and-ball .44 and hung it on a willer limb reching out over the water. They was thick bushes all around the stream.

Well, I div deep, and as I come up, I had a feeling like somebody had hit me over the head with a club. I looked up, and there was a Injun holding on to a limb with one hand and leaning out over the water with a club in the other hand.

He yelled and swung at me again, but I div, and he missed, and I come up right under the limb where my gun was hung. I reched up and grabbed it and let bam at him just as he dived into the bushes, and he let out a squall and grabbed the seat of his pants. Next minute I heard a horse running, and glimpsed him tearing away through the bresh on a pinto mustang, setting his hoss like it was a red-hot stove, and dern him, he had my clothes in one hand! I was so upsot by this that I missed him clean, and jumping out, I charged through the bushes and saplings, but he was already out of sight. I knowed it warn’t likely he was with a war-party—just a dern thieving Piute—but what a fix I was in! He’d even stole my moccasins.

I couldn’t go home, in that shape, without the letter, and admit I missed a Injun twice. Pap would larrup the tar out of me. And if I went on, what if I met some women, in the valley settlements? I don’t reckon they ever was a young’un half as bashful as what I was in them days. Cold sweat busted out all over me. I thought, here I started out to see the world and show Glory McGraw I was a man among men, and here I am with no more clothes than a jackrabbit. At last, in desperation, I buckled on my belt and started down the trail towards Tomahawk. I was about ready to commit murder to get me some pants.

I was glad the Injun didn’t steal Alexander, but the going was so rough I had to walk and lead him, because I kept to the thick bresh alongside the trail. He had a tough time getting through the bushes, and the thorns scratched him so he hollered, and ever’ now and then I had to lift him over jagged rocks. It was tough on Alexander, but I was too bashful to travel in the open trail without no clothes on.

After I’d gone maybe a mile I heard somebody in the trail ahead of me, and peeking through the bushes, I seen a most pecooliar sight. It was a man on foot, going the same direction as me, and he had on what I instinctly guessed was city clothes. They warn’t buckskin nor homespun, nor yet like the duds Mister Wilkinson had on, but they were very beautiful, with big checks and stripes all over ’em. He had on a round hat with a narrer brim, and shoes like I hadn’t never seen before, being neither boots nor moccasins. He was dusty, and he cussed considerable as he limped along. Ahead of him I seen the trail made a hoss-shoe bend, so I cut straight across and got ahead of him, and as he come along, I come out of the bresh and throwed down on him with my cap-and-ball.

He throwed up his hands and hollered: “Don’t shoot!”

“I don’t want to, mister,” I said, “but I got to have clothes!”

He shook his head like he couldn’t believe I was so, and he said: “You ain’t the color of a Injun, but—what kind of people live in these hills, anyway?”

“Most of ’em’s Democrats,” I said. “But I ain’t got no time to talk politics. You climb out of them riggin’s.”

“My God!” he wailed. “My horse threw me off and ran away, and I’ve bin walkin’ for hours, expecting to get scalped by Injuns any minute, and now a naked lunatic on a mule demands my clothes! It’s too dern much!”

“I cain’t argy, mister,” I said; “somebody’s liable to come up the trail any minute. Hustle!” So saying I shot his hat off to encourage him.

He give a howl and shucked his duds in a hurry.

“My underclothes, too?” he demanded, shivering though it was very hot.

“Is that what them things is?” I demanded, shocked. “I never heard of a man wearin’ such womanish things. The country is goin’ to the dogs, just like pap says. You better git goin’. Take my mule. When I git to where I can git some regular clothes, we’ll swap back.”

He clumb onto Alexander kind of dubious, and says to me, despairful: “Will you tell me one thing—how do I get to Tomahawk?”

“Take the next turn to the right,” I said, “and—”

Jest then Alexander turned his head and seen them underclothes on his back, and he give a loud and ringing bray and sot sail down the trail at full speed with the stranger hanging on with both hands. Before they was out of sight they come to where the trail forked, and Alexander taken the left branch instead of the right, and vanished amongst the ridges.

I put on the clothes, and they scratched my hide something fierce. I thinks, well, I got store-bought clothes quicker’n I hoped to. But I didn’t think much of ’em. The coat split down the back, and the pants was too short, but the shoes was the wust; they pinched all over. I throwed away the socks, having never wore none, but put on what was left of the hat.

I went on down the trail, and taken the right-hand fork, and in a mile or so I come out on a flat, and heard hosses running. The next thing a mob of men on hosses bust into view. One of ’em yelled: “There he is!” and they all come for me full tilt. Instantly I decided that the stranger had got to Tomahawk after all, somehow, and had sot his friends onto me for stealing his clothes.

So I left the trail and took out across the sage grass, and they all charged after me, yelling stop. Well, them dern shoes pinched my feet so bad I couldn’t make much speed, so after I had run maybe a quarter of a mile I perceived that the hosses were beginning to gain on me. So I wheeled with my cap-and-ball in my hand, but I was going so fast, when I turned, them dern shoes slipped and I went over backwards into a cactus bed just as I pulled the trigger. So I only knocked the hat off of the first hossman. He yelled and pulled up his hoss, right over me nearly, and as I drawed another bead on him, I seen he had a bright shiny star on to his shirt. I dropped my gun and stuck up my hands.

They swarmed around me—cowboys, from their looks. The man with the star got off his hoss and picked up my gun and cussed.

“What did you lead us this chase through this heat and shoot at me for?” he demanded.

“I didn’t know you was a officer,” I said.

“Hell, McVey,” said one of ’em, “you know how jumpy tenderfeet is. Likely he thought we was Santry’s outlaws. Where’s yore hoss?”

“I ain’t got none,” I said.

“Got away from you, hey?” said McVey. “Well, climb up behind Kirby here, and let’s git goin’.”

To my surprise, the sheriff stuck my gun back in the scabbard, and so I clumb up behind Kirby, and away we went. Kirby kept telling me not to fall off, and it made me mad, but I said nothing. After an hour or so we come to a bunch of houses they said was Tomahawk. I got panicky when I seen all them houses, and would have jumped down and run for the mountains, only I knowed they’d catch me, with them dern pinchy shoes on.

I hadn’t never seen such houses before. They was made out of boards, mostly, and some was two stories high. To the north-west and west the hills riz up a few hundred yards from the backs of the houses, and on the other sides there was plains, with bresh and timber on them.

“You boys ride into town and tell the folks that the shebang starts soon,” said McVey. “Me and Kirby and Richards will take him to the ring.”

I could see people milling around in the streets, and I never had no idee they was that many folks in the world. The sheriff and the other two fellers rode around the north end of the town and stopped at a old barn and told me to get off. So I did, and we went in and they had a kind of room fixed up in there with benches and a lot of towels and water buckets, and the sheriff said: “This ain’t much of a dressin’ room, but it’ll have to do. Us boys don’t know much about this game, but we’ll second you as good as we can. One thing—the other feller ain’t got no manager nor seconds neither. How do you feel?”

“Fine,” I said, “but I’m kind of hungry.”

“Go git him somethin’, Richards,” said the sheriff.

“I didn’t think they et just before a bout,” said Richards.

“Aw, I reckon he knows what he’s doin’,” said McVey. “Gwan.”

So Richards pulled out, and the sheriff and Kirby walked around me like I was a prize bull, and felt my muscles, and the sheriff said: “By golly, if size means anything, our dough is as good as in our britches right now!”

I pulled my dollar out of my scabbard and said I would pay for my keep, and they haw-hawed and slapped me on the back and said I was a great joker. Then Richards come back with a platter of grub, with a lot of men wearing boots and guns and whiskers, and they stomped in and gawped at me, and McVey said: “Look him over, boys! Tomahawk stands or falls with him today!”

They started walking around me like him and Kirby done, and I was embarrassed and et three or four pounds of beef and a quart of mashed pertaters, and a big hunk of white bread, and drunk about a gallon of water, because I was purty thirsty. Then they all gaped like they was surprised about something, and one of ’em said: “How come he didn’t arrive on the stagecoach yesterday?”

“Well,” said the sheriff, “the driver told me he was so drunk they left him at Bisney, and come on with his luggage, which is over there in the corner. They got a hoss and left it there with instructions for him to ride on to Tomahawk as soon as he sobered up. Me and the boys got nervous today when he didn’t show up, so we went out lookin’ for him, and met him hoofin’ it down the trail.”

“I bet them Perdition hombres starts somethin’,” said Kirby. “Ain’t a one of ’em showed up yet. They’re settin’ over at Perdition soakin’ up bad licker and broodin’ on their wrongs. They shore wanted this show staged over there. They claimed that since Tomahawk was furnishin’ one-half of the attraction, and Gunstock the other half, the razee ought to be throwed at Perdition.”

“Nothin’ to it,” said McVey. “It laid between Tomahawk and Gunstock, and we throwed a coin and won it. If Perdition wants trouble she can git it. Is the boys r’arin’ to go?”

“Is they!” says Richards. “Every bar in Tomahawk is crowded with hombres full of licker and civic pride. They’re bettin’ their shirts, and they has been nine fights already. Everybody in Gunstock’s here.”

“Well, le’s git goin’,” says McVey, getting nervous. “The quicker it’s over, the less blood there’s likely to be spilt.”

The first thing I knowed, they had laid hold of me and was pulling my clothes off, so it dawned on me that I must be under arrest for stealing that stranger’s clothes. Kirby dug into the baggage which was in one corner of the stall, and dragged out a funny looking pair of pants; I know now they was white silk. I put ’em on because I didn’t have nothing else to put on, and they fitted me like my skin. Richards tied a American flag around my waist, and they put some spiked shoes onto my feet.

I let ’em do like they wanted to, remembering what pap said about not resisting no officer. Whilst so employed I begun to hear a noise outside, like a lot of people whooping and cheering. Purty soon in come a skinny old gink with whiskers and two guns on, and he hollered: “Lissen here, Mac, dern it, a big shipment of gold is down there waitin’ to be took off by the evenin’ stage, and the whole blame town is deserted on account of this dern foolishness. Suppose Comanche Santry and his gang gits wind of it?”

“Well,” said McVey, “I’ll send Kirby here to help you guard it.”

“You will like hell,” says Kirby. “I’ll resign as deputy first. I got every cent of my dough on this scrap, and I aim to see it.”

“Well, send somebody!” says the old codger. “I got enough to do runnin’ my store, and the stage stand, and the post office, without—”

He left, mumbling in his whiskers, and I said: “Who’s that?”

“Aw,” said Kirby, “that’s old man Brenton that runs the store down at the other end of town, on the east side of the street. The post office is in there, too.”

“I got to see him,” I says. “There’s a letter—”

Just then another man come surging in and hollered: “Hey, is yore man ready? Folks is gittin’ impatient!”

“All right,” says McVey, throwing over me a thing he called a bathrobe. Him and Kirby and Richards picked up towels and buckets and things, and we went out the oppersite door from what we come in, and they was a big crowd of people there, and they whooped and shot off their pistols. I would have bolted back into the barn, only they grabbed me and said it was all right. We pushed through the crowd, and I never seen so many boots and pistols in my life, and we come to a square corral made out of four posts sot in the ground, and ropes stretched between. They called this a ring and told me to get in. I done so, and they had turf packed down so the ground was level as a floor and hard and solid. They told me to set down on a stool in one corner, and I did, and wrapped my robe around me like a Injun.

Then everybody yelled, and some men, from Gunstock, McVey said, clumb through the ropes on the other side. One of ’em was dressed like I was, and I never seen such a funny-looking human. His ears looked like cabbages, and his nose was plumb flat, and his head was shaved and looked right smart like a bullet. He sot down in a oppersite corner.

Then a feller got up and waved his arms, and hollered: “Gents, you all know the occasion of this here suspicious event. Mister Bat O’Tool, happenin’ to be passin’ through Gunstock, consented to fight anybody which would meet him. Tomahawk riz to the occasion by sendin’ all the way to Denver to procure the services of Mister Bruiser McGoorty, formerly of San Francisco!”

He p’inted at me, and everybody cheered and shot off their pistols, and I was embarrassed and bust out in a cold sweat.

“This fight,” said the feller, “will be fit accordin’ to London Prize Ring Rules, same as in a champeenship go. Bare fists, round ends when one of ’em’s knocked down or throwed down. Fight lasts till one or t’other ain’t able to come up to the scratch when time’s called. I, Yucca Blaine, have been selected as referee because, bein’ from Chawed Ear, I got no prejudices either way. Air you all ready? Time!”

McVey hauled me off my stool and pulled off my bathrobe and pushed me out into the ring. I nearly died with embarrassment, but I seen the feller they called O’Tool didn’t have on no more clothes than me. He approached and held out his hand like he wanted to shake hands, so I held out mine. We shook hands, and then without no warning he hit me a awful lick on the jaw with his left. It was like being kicked by a mule. The first part of me which hit the turf was the back of my head. O’Tool stalked back to his corner, and the Gunstock boys was dancing and hugging each other, and the Tomahawk fellers was growling in their whiskers and fumbling with their guns and bowie knives.

McVey and his deperties rushed into the ring before I could get up and dragged me to my corner and began pouring water on me.

“Air you hurt much?” yelled McVey.

“How can a man’s fist hurt anybody?” I ast. “I wouldn’t of fell down, only I was caught off-guard. I didn’t know he was goin’ to hit me. I never played no game like this here’n before.”

McVey dropped the towel he was beating me in the face with, and turned pale. “Ain’t you Bruiser McGoorty of San Francisco?” he hollered.

“Naw,” I said. “I’m Breckinridge Elkins, from up in the Humbolt Mountains. I come here to git a letter for pap.”

“But the stagecoach driver described them clothes—” he begun wildly.

“A Injun stole my clothes,” I explained, “so I taken some off’n a stranger. Maybe that was Mister McGoorty.”

“What’s the matter?” ast Kirby, coming up with another bucket of water. “Time’s about ready to be called.”

“We’re sunk!” bawled McVey. “This ain’t McGoorty! This is a derned hillbilly which murdered McGoorty and stole his clothes!”

“We’re rooint!” exclaimed Richards, aghast. “Everybody’s bet their dough without even seein’ our man, they was that full of trust and civic pride. We cain’t call it off now. Tomahawk is rooint! What’ll we do?”

“He’s goin’ to git in there and fight his derndest,” said McVey, pulling his gun and jamming it into my back. “We’ll hang him after the fight.”

“But he cain’t box!” wailed Richards.

“No matter,” said McVey; “the fair name of our town is at stake; Tomahawk promised to supply a fighter to fight O’Tool, and—”

“Oh!” I said, suddenly seeing light. “This here is a fight then, ain’t it?”

McVey give a low moan, and Kirby reched for his gun, but just then the referee hollered time, and I jumped up and run at O’Tool. If a fight was all they wanted, I was satisfied. All that talk about rules, and the yelling of the crowd and all had had me so confused I hadn’t knowed what it was all about. I hit at O’Tool and he ducked and hit me in the belly and on the nose and in the eye and on the ear. The blood spurted, and the crowd hollered, and he looked plumb dumbfounded and gritted betwixt his teeth: “Are you human? Why don’t you fall?”

I spit out a mouthful of blood and got my hands on him and started chawing his ear, and he squalled like a catamount. Yucca run in and tried to pull me loose and I give him a slap under the ear and he turned a somersault into the ropes.

“Yore man’s fightin’ foul!” he squalled, and Kirby said: “Yo’re crazy! Do you see this gun? You holler ‘foul’ just once more, and it’ll go off!”

Meanwhile O’Tool had broke loose from me and caved in his knuckles on my jaw, and I come for him again, because I was beginning to lose my temper. He gasped: “If you want to make an alley-fight out of it, all right. I wasn’t raised in Five Points for nothing!” He then rammed his knee into my groin, and groped for my eye, but I got his thumb in my teeth and begun masticating it, and the way he howled was a caution.

By this time the crowd was crazy, and I throwed O’Tool and begun to stomp him, when somebody let bang at me from the crowd and the bullet cut my silk belt and my pants started to fall down.

I grabbed ’em with both hands, and O’Tool riz up and rushed at me, bloody and bellering, and I didn’t dare let go my pants to defend myself. I whirled and bent over and lashed out backwards with my right heel like a mule, and I caught him under the chin. He done a cartwheel in the air, his head hit the turf, and he bounced on over and landed on his back with his knees hooked over the lower rope. There warn’t no question about him being out. The only question was, was he dead?

A roar of “Foul!” went up from the Gunstock men, and guns bristled all around the ring.

The Tomahawk men was cheering and yelling that I’d won fair and square, and the Gunstock men was cussing and threatening me, when somebody hollered: “Leave it to the referee!”

“Sure,” said Kirby. “He knows our man won fair, and if he don’t say so, I’ll blow his head off!”

“That’s a lie!” bellered a Gunstock man. “He knows it war a foul, and if he says it warn’t, I’ll kyarve his gizzard with this here bowie knife!”

At them words Yucca fainted, and then a clatter of hoofs sounded above the din, and out of the timber that hid the trail from the east a gang of hossmen rode at a run. Everybody yelled: “Look out, here comes them Perdition illegitimates!”

Instantly a hundred guns covered ’em, and McVey demanded: “Come ye in peace or in war?”

“We come to unmask a fraud!” roared a big man with a red bandanner around his neck. “McGoorty, come forth!”

A familiar figger, now dressed in cowboy togs, pushed forward on my mule. “There he is!” this figger yelled, p’inting a accusing finger at me. “That’s the desperado that robbed me! Them’s my tights he’s got on!”

“What is this?” roared the crowd.

“A cussed fake!” bellered the man with the red bandanner. “This here is Bruiser McGoorty!”

“Then who’s he?” somebody bawled, p’inting at me.

“I’m Breckinridge Elkins and I can lick any man here!” I roared, getting mad. I brandished my fists in defiance, but my britches started sliding down again, so I had to shut up and grab ’em.

“Aha!” the man with the red bandanner howled like a hyener. “He admits it! I dunno what the idee is, but these Tomahawk polecats has double-crossed somebody! I trusts that you jackasses from Gunstock realizes the blackness and hellishness of their hearts! This man McGoorty rode into Perdition a few hours ago in his unmentionables, astraddle of that there mule, and told us how he’d been held up and robbed and put on the wrong road. You skunks was too proud to stage this fight in Perdition, but we ain’t the men to see justice scorned with impunity! We brought McGoorty here to show you that you was bein’ gypped by Tomahawk! That man ain’t no prize fighter; he’s a highway robber!”

“These Tomahawk coyotes has framed us!” squalled a Gunstock man, going for his gun.

“Yo’re a liar!” roared Richards, bending a .45 barrel over his head.

The next instant guns was crashing, knives was gleaming, and men was yelling blue murder. The Gunstock braves turned frothing on the Tomahawk warriors, and the men from Perdition, yelping with glee, pulled their guns, and begun fanning the crowd indiscriminately, which give back their fire. McGoorty give a howl and fell down on Alexander’s neck, gripping around it with both arms, and Alexander departed in a cloud of dust and gun-smoke.

I grabbed my gunbelt, which McVey had hung over the post in my corner, and I headed for cover, holding onto my britches whilst the bullets hummed around me as thick as bees. I wanted to take to the bresh, but I remembered that blamed letter, so I headed for town. Behind me there riz a roar of banging guns and yelling men. Jest as I got to the backs of the row of buildings which lined the street, I run head on into something soft. It was McGoorty, trying to escape on Alexander. He had hold of jest one rein, and Alexander, evidently having rounded one end of the town, was traveling in a circle and heading back where he started from.

I was going so fast I couldn’t stop, and I run right over Alexander and all three of us went down in a heap. I jumped up, afeared Alexander was kilt or crippled, but he scrambled up snorting and trembling, and then McGoorty weaved up, making funny noises. I poked my cap-and-ball into his belly.

“Off with them pants!” I hollered.

“My God!” he screamed. “Again? This is getting to be a habit!”

“Hustle!” I bellered. “You can have these scandals I got on now.”

He shucked his britches and grabbed them tights and run like he was afeared I’d want his underwear too. I jerked on the pants, forked Alexander and headed for the south end of town. I kept behind the houses, though the town seemed to be deserted, and purty soon I come to the store where Kirby had told me old man Brenton kept the post office. Guns was barking there, and across the street I seen men ducking in and out behind a old shack, and shooting.

I tied Alexander to a corner of the store and went in the back door. Up in the front part I seen old man Brenton kneeling behind some barrels with a .45-90, and he was shooting at the fellers in the shack acrost the street. Every now and then a slug would hum through the door and comb his whiskers, and he would cuss worse’n pap did that time he sot down in a b’ar trap.

I went up to him and tapped him on the shoulder and he give a squall and flopped over and let go bam! right in my face and singed off my eyebrows. And the fellers acrost the street hollered and started shooting at both of us.

I’d grabbed the barrel of his Winchester, and he was cussing and jerking at it with one hand and feeling in his boot for a knife with the other’n, and I said: “Mister Brenton, if you ain’t too busy, I wish you’d gimme that there letter which come for pap.”

“Don’t never come up behind me like that again!” he squalled. “I thought you was one of them dern outlaws! Look out! Duck, you blame fool!”

I let go of his gun, and he taken a shot at a head which was aiming around the corner of the shack, and the head let out a squall and disappeared.

“Who is them fellers?” I ast.

“Comanche Santry and his bunch, from up in the hills,” snarled old man Brenton, jerking the lever of his Winchester. “They come after that gold. A hell of a sheriff McVey is; never sent me nobody. And them fools over at the ring are makin’ so much noise they’ll never hear the shootin’ over here. Look out, here they come!”

Six or seven men rushed out from behind the shack and run acrost the street, shooting as they come. I seen I’d never get my letter as long as all this fighting was going on, so I unslung my old cap-and-ball and let bam at them three times, and three of them outlaws fell acrost each other in the street, and the rest turned around and run back behind the shack.

“Good work, boy!” yelled old man Brenton. “If I ever—oh, Judas Iscariot, we’re blowed up now!”

Something was pushed around the corner of the shack and come rolling down towards us, the shack being on higher ground than what the store was. It was a keg, with a burning fuse which whirled as the keg revolved and looked like a wheel of fire.

“What’s in that there kaig?” I ast.

“Blastin’ powder!” screamed old man Brenton, scrambling up. “Run, you dern fool! It’s comin’ right into the door!”

He was so scairt he forgot all about the fellers acrost the street, and one of ’em caught him in the thigh with a buffalo rifle, and he plunked down again, howling blue murder. I stepped over him to the door—that’s when I got that slug in my hip—and the keg hit my laigs and stopped, so I picked it up and heaved it back acrost the street. It hadn’t no more’n hit the shack when bam! it exploded and the shack went up in smoke. When it stopped raining pieces of wood and metal, they warn’t no sign to show any outlaws had ever hid behind where that shack had been.

“I wouldn’t believe it if I hadn’t saw it myself,” old man Brenton moaned faintly.

“Air you hurt bad, Mister Brenton?” I ast.

“I’m dyin’,” he groaned.

“Well, before you die, Mister Brenton,” I says, “would you mind givin’ me that there letter for pap?”

“What’s yore pap’s name?” he ast.

“Roarin’ Bill Elkins, of Bear Creek,” I said.

He warn’t as bad hurt as he thought. He reched up and got hold of a leather bag and fumbled in it and pulled out a envelope. “I remember tellin’ old Buffalo Rogers I had a letter for Bill Elkins,” he said, fingering it over. Then he said: “Hey, wait! This ain’t for yore pap. My sight is gittin’ bad. I read it wrong the first time. This here is for Bill Elston that lives between here and Perdition.”

I want to spike a rumor which says I tried to murder old man Brenton and tore down his store for spite. I’ve done told how he got his laig broke, and the rest was accidental. When I realized that I had went through all that embarrassment for nothing, I was so mad and disgusted I turned and run out of the back door, and I forgot to open the door and that’s how it got tore off the hinges.

I then jumped on to Alexander and forgot to ontie him loose from the store. I kicked him in the ribs, and he bolted and tore loose that corner of the building and that’s how come the roof to fall in. Old man Brenton inside was scairt and started yelling bloody murder, and about that time a mob of men come up to investigate the explosion which had stopped the three-cornered battle between Perdition, Tomahawk and Gunstock, and they thought I was the cause of everything, and they all started shooting at me as I rode off.

Then was when I got that charge of buckshot in my back.

I went out of Tomahawk and up the hill trail so fast I bet me and Alexander looked like a streak; and I says to myself it looks like making a name for myself in the world is going to be tougher than I thought, because it’s evident that civilization is full of snares for a boy which ain’t reched his full growth and strength.

I didn’t pull up Alexander till I was plumb out of sight of Tomahawk. Then I slowed down and taken stock of myself, and my spirits was right down in my spiked shoes which still had some of Mister O’Tool’s hide stuck onto the spikes. Here I’d started forth into the world to show Glory McGraw what a he-bearcat I was, and now look at me. Here I was without even no clothes but them derned spiked shoes which pinched my feet, and a pair of britches some cow-puncher had wore the seat out of and patched with buckskin. I still had my gunbelt and the dollar pap gimme, but no place to spend it. I likewise had a goodly amount of lead under my hide.

“By golly!” I says, shaking my fists at the universe at large. “I ain’t goin’ to go back to Bear Creek like this, and have Glory McGraw laughin’ at me! I’ll head for the Wild River settlements and git me a job punchin’ cows till I got money enough to buy me store-bought boots and a hoss!”

I then pulled out my bowie knife which was in a scabbard on my gunbelt, and started digging the slug out of my hip, and the buckshot out of my back. Them buckshot was kinda hard to get to, but I done it. I hadn’t never held a job of punching cows, but I’d had plenty experience roping wild bulls up in the Humbolts. Them bulls wanders off the lower ranges into the mountains and grows most amazing big and mean. Me and Alexander had had plenty experience with them, and I had me a lariat which would hold any steer that ever bellered. It was still tied to my saddle, and I was glad none of them cowpunchers hadn’t stole it. Maybe they didn’t know it was a lariat. I’d made it myself, especial, and used it to rope them bulls and also cougars and grizzlies which infests the Humbolts. It was made out of buffalo hide, ninety foot long and half again as thick and heavy as the average lariat, and the honda was a half-pound chunk of iron beat into shape with a sledge hammer. I reckoned I was qualified for a vaquero even if I didn’t have no cowboy clothes and was riding a mule.

So I headed acrost the mountains for the cowcountry. They warn’t no trail the way I taken, but I knowed the direction Wild River lay in, and that was enough for me. I knowed if I kept going that way I’d hit it after awhile. Meanwhile, they was plenty of grass in the draws and along the creeks to keep Alexander fat and sleek, and plenty of squirrels and rabbits for me to knock over with rocks. I camped that night away up in the high ranges and cooked me nine or ten squirrels over a fire and et ’em, and while that warn’t much of a supper for a appertite like mine, still I figgered next day I’d stumble on to a b’ar or maybe a steer which had wandered offa the ranges.

Next morning before sunup I was on Alexander and moving on, without no breakfast, because it looked like they warn’t no rabbits nor nothing near abouts, and I rode all morning without sighting nothing. It was a high range, and nothing alive there but a buzzard I seen onst, but late in the afternoon I crossed a backbone and come down into a whopping big plateau about the size of a county, with springs and streams and grass growing stirrup-high along ’em, and clumps of cottonwood, and spruce, and pine thick up on the hillsides. They was canyons and cliffs, and mountains along the rim, and altogether it was as fine a country as I ever seen, but it didn’t look like nobody lived there, and for all I know I was the first white man that ever come into it. But they was more soon, as I’ll relate.

Well, I noticed something funny as I come down the ridge that separated the bare hills from the plateau. First I met a wildcat. He come lipping along at a right smart clip, and he didn’t stop. He just gimme a wicked look sidewise and kept right on up the slope. Next thing I met a lobo wolf, and after that I counted nine more wolves, and they was all heading west, up the slopes. Then Alexander give a snort and started trembling, and a cougar slid out of a blackjack thicket and snarled at us over his shoulder as he went past at a long lope. All them varmints was heading for the dry bare country I’d just left, and I wondered why they was leaving a good range like this one to go into that dern no-account country.

It worried Alexander too, because he smelt of the air and brayed kind of plaintively. I pulled him up and smelt the air too, because critters run like that before a forest fire, but I couldn’t smell no smoke, nor see none. So I rode on down the slopes and started across the flats, and as I went I seen more bobcats, and wolves, and painters, and they was all heading west, and they warn’t lingering none, neither. They warn’t no doubt that them critters was pulling their freight because they was scairt of something, and it warn’t humans, because they didn’t ’pear to be scairt of me a mite. They just swerved around me and kept trailing. After I’d gone a few miles I met a herd of wild hosses, with the stallion herding ’em. He was a big mean-looking cuss, but he looked scairt as bad as any of the critters I’d saw.

The sun was getting low, and I was getting awful hungry as I come into a open spot with a creek on one side running through clumps of willers and cottonwoods, and on the other side I could see some big cliffs looming up over the tops of the trees. And whilst I was hesitating, wondering if I ought to keep looking for eatable critters, or try to worry along on a wildcat or a wolf, a big grizzly come lumbering out of a clump of spruces and headed west. When he seen me and Alexander he stopped and snarled like he was mad about something, and then the first thing I knowed he was charging us. So I pulled my .44 and shot him through the head, and got off and onsaddled Alexander and turnt him loose in grass stirrup-high, and skun the b’ar. Then I cut me off some steaks and started a fire and begun reducing my appertite. That warn’t no small job, because I hadn’t had nothing to eat since the night before.

Well, while I was eating I heard hosses and looked up and seen six men riding towards me from the east. One was as big as me, but the other ones warn’t but about six foot tall apiece. They was cowpunchers, by their look, and the biggest man was dressed plumb as elegant as Mister Wilkinson was, only his shirt was jest only one color. But he had on fancy boots and a white Stetson and a ivory-butted Colt, and what looked like the butt of a sawed-off shotgun jutted out of his saddle-scabbard. He was dark and had awful mean eyes, and a jaw which it looked like he could bite the spokes out of a wagon wheel if he wanted to.

He started talking to me in Piute, but before I could say anything, one of the others said: “Aw, that ain’t no Injun, Donovan, his eyes ain’t the right color.”

“I see that, now,” says Donovan. “But I shore thought he was a Injun when I first rode up and seen them old ragged britches and his sunburnt hide. Who the devil air you?”

“I’m Breckinridge Elkins, from Bear Creek,” I says, awed by his magnificence.

“Well,” says he, “I’m Wild Bill Donovan, which name is heard with fear and tremblin’ from Powder River to the Rio Grande. Just now I’m lookin’ for a wild stallion. Have you seen sech?”

“I seen a bay stallion headin’ west with his herd,” I said.

“ ’Twarn’t him,” says Donovan. “This here one’s a pinto, the biggest, meanest hoss in the world. He come down from the Humbolts when he was a colt, but he’s roamed the West from Border to Border. He’s so mean he ain’t never got him a herd of his own. He takes mares away from other stallions, and then drifts on alone just for pure cussedness. When he comes into a country all other varmints takes to the tall timber.”

“You mean the wolves and painters and b’ars I seen headin’ for the high ridges was runnin’ away from this here stallion?” I says.

“Exactly,” says Donovan. “He crossed the eastern ridge sometime durin’ the night, and the critters that was wise high-tailed it. We warn’t far behind him; we come over the ridge a few hours ago, but we lost his trail somewhere on this side.”

“You chasin’ him?” I ast.

“Ha!” snarled Donovan with a kind of vicious laugh. “The man don’t live what can chase Cap’n Kidd! We’re just follerin’ him. We been follerin’ him for five hundred miles, keepin’ outa sight, and hopin’ to catch him off guard or somethin’. We got to have some kind of a big advantage before we closes in, or even shows ourselves. We’re right fond of life! That devil has kilt more men than any other ten hosses on this continent.”

“What you call him?” I says.

“Cap’n Kidd,” says Donovan. “Cap’n Kidd was a big pirate long time ago. This here hoss is like him in lots of ways, particularly in regard to morals. But I’ll git him, if I have to foller him to the Gulf and back. Wild Bill Donovan always gits what he wants, be it money, woman, or hoss! Now lissen here, you range-country hobo: we’re a-siftin’ north from here, to see if we cain’t pick up Cap’n Kidd’s sign. If you see a pinto stallion bigger’n you ever dreamed a hoss could be, or come onto his tracks, you drop whatever yo’re doin’ and pull out and look for us, and tell me about it. You keep lookin’ till you find us, too. If you don’t you’ll regret it, you hear me?”

“Yessir,” I said. “Did you gents come through the Wild River country?”

“Maybe we did and maybe we didn’t,” he says with haughty grandeur. “What business is that of yore’n, I’d like to know?”

“Not any,” I says. “But I was aimin’ to go there and see if I could git me a job punchin’ cows.”

At that he throwed back his head and laughed long and loud, and all the other fellers laughed too, and I was embarrassed.

“You git a job punchin’ cows?” roared Donovan. “With them britches and shoes, and not even no shirt, and that there ignorant-lookin’ mule I see gobblin’ grass over by the creek? Haw! haw! haw! haw! You better stay up here in the mountains whar you belong and live on roots and nuts and jackrabbits like the other Piutes, red or white! Any self-respectin’ rancher would take a shotgun to you if you was to ast him for a job. Haw! haw! haw!” he says, and rode off still laughing.

I was that embarrassed I bust out into a sweat. Alexander was a good mule, but he did look kind of funny in the face. But he was the only critter I’d ever found which could carry my weight very many miles without giving plumb out. He was awful strong and tough, even if he was kind of dumb and pot-bellied. I begun to get kind of mad, but Donovan and his men was already gone, and the stars was beginning to blink out. So I cooked me some more b’ar steaks and et ’em, and the land sounded awful still, not a wolf howling nor a cougar squalling. They was all west of the ridge. This critter Cap’n Kidd sure had the country to hisself, as far as the meat-eating critters was consarned.

I hobbled Alexander close by and fixed me a bed with some boughs and his saddle blanket, and went to sleep. I was woke up shortly after midnight by Alexander trying to get in bed with me.

I sot up in irritation and prepared to bust him in the snoot, when I heard what had scairt him. I never heard such a noise. My hair stood straight up. It was a stallion neighing, but I never heard no hoss critter neigh like that. I bet you could of heard it for fifteen miles. It sounded like a combination of a wild hoss neighing, a rip saw going through a oak log full of knots, and a hungry cougar screeching. I thought it come from somewhere within a mile of the camp, but I warn’t sure. Alexander was shivering and whimpering he was that scairt, and stepping all over me as he tried to huddle down amongst the branches and hide his head under my shoulder. I shoved him away, but he insisted on staying as close to me as he could, and when I woke up again next morning he was sleeping with his head on my belly.

But he must of forgot about the neigh he heard, or thought it was jest a bad dream or something, because as soon as I taken the hobbles off of him he started cropping grass and wandered off amongst the thickets in his pudding-head way.

I cooked me some more b’ar steaks, and wondered if I ought to go and try to find Mister Donovan and tell him about hearing the stallion neigh, but I figgered he’d heard it. Anybody that was within a day’s ride ought to of heard it. Anyway, I seen no reason why I should run errands for Donovan.

I hadn’t got through eating when I heard Alexander give a horrified bray, and he come lickety-split out of a grove of trees and made for the camp, and behind him come the biggest hoss I ever seen in my life. Alexander looked like a pot-bellied bull pup beside of him. He was painted—black and white—and he r’ared up with his long mane flying agen the sunrise, and give a scornful neigh that nigh busted my ear-drums, and turned around and sa’ntered back towards the grove, cropping grass as he went, like he thunk so little of Alexander he wouldn’t even bother to chase him.

Alexander come blundering into camp, blubbering and hollering, and run over the fire and scattered it every which away, and then tripped hisself over the saddle which was laying nearby, and fell on his neck braying like he figgered his life was in danger.

I catched him and throwed the saddle and bridle on to him, and by that time Cap’n Kidd was out of sight on the other side of the thicket. I onwound my lariat and headed in that direction. I figgered not even Cap’n Kidd could break that lariat. Alexander didn’t want to go; he sot back on his haunches and brayed fit to deefen you, but I spoke to him sternly, and it seemed to convince him that he better face the stallion than me, so he moved out, kind of reluctantly.

We went past the grove and seen Cap’n Kidd cropping grass in the patch of rolling prairie just beyond, so I rode towards him, swinging my lariat. He looked up and snorted kinda threateningly, and he had the meanest eye I ever seen in man or beast; but he didn’t move, just stood there looking contemptuous, so I throwed my rope and piled the loop right around his neck, and Alexander sot back on his haunches.

Well, it was about like roping a roaring hurricane. The instant he felt that rope Cap’n Kidd give a convulsive start, and made one mighty lunge for freedom. The lariat held, but the girths didn’t. They held jest long enough for Alexander to get jerked head over heels, and naturally I went along with him. But right in the middle of the somesault we taken, both girths snapped.

Me and the saddle and Alexander landed all in a tangle, but Cap’n Kidd jerked the saddle from amongst us, because I had my rope tied fast to the horn, Texas-style, and Alexander got loose from me by the simple process of kicking me vi’lently in the ear. He also stepped on my face when he jumped up, and the next instant he was high-tailing it through the bresh in the general direction of Bear Creek. As I learned later he didn’t stop till he run into pap’s cabin and tried to hide under my brother John’s bunk.

Meanwhile Cap’n Kidd had throwed the loop offa his head and come for me with his mouth wide open, his ears laid back and his teeth and eyes flashing. I didn’t want to shoot him, so I riz up and run for the trees. But he was coming like a tornado, and I seen he was going to run me down before I could get to a tree big enough to climb, so I grabbed me a sapling about as thick as my laig and tore it up by the roots, and turned around and busted him over the head with it, just as he started to r’ar up to come down on me with his front hoofs.

Pieces of roots and bark and wood flew every which a way, and Cap’n Kidd grunted and batted his eyes and went back on to his haunches. It was a right smart lick. If I’d ever hit Alexander that hard it would have busted his skull like a egg—and Alexander had a awful thick skull, even for a mule.

Whilst Cap’n Kidd was shaking the bark and stars out of his eyes, I run to a big oak and clumb it. He come after me instantly, and chawed chunks out of the tree as big as washtubs, and kicked most of the bark off as high up as he could rech, but it was a good substantial tree, and it held. He then tried to climb it, which amazed me most remarkable, but he didn’t do much good at that. So he give up with a snort of disgust and trotted off.

I waited till he was out of sight, and then I clumb down and got my rope and saddle, and started follering him. I knowed there warn’t no use trying to catch Alexander with the lead he had. I figgered he’d get back to Bear Creek safe. And Cap’n Kidd was the critter I wanted now. The minute I lammed him with that tree and he didn’t fall, I knowed he was the hoss for me—a hoss which could carry my weight all day without giving out, and likewise full of spirit. I says to myself I rides him or the buzzards picks my bones.

I snuck from tree to tree, and presently seen Cap’n Kidd swaggering along and eating grass, and biting the tops off of young sapling, and occasionally tearing down a good sized tree to get the leaves off. Sometimes he’d neigh like a steamboat whistle, and let his heels fly in all directions just out of pure cussedness. When he done this the air was full of flying bark and dirt and rocks till it looked like he was in the middle of a twisting cyclone. I never seen such a critter in my life. He was as full of pizen and rambunctiousness as a drunk Apache on the warpath.

I thought at first I’d rope him and tie the other end of the rope to a big tree, but I was a-feared he’d chawed the lariat apart. Then I seen something that changed my mind. We was close to the rocky cliffs which jutted up above the trees, and Cap’n Kidd was passing a canyon mouth that looked like a big knife cut. He looked in and snorted, like he hoped they was a mountain lion hiding in there, but they warn’t, so he went on. The wind was blowing from him towards me and he didn’t smell me.

After he was out of sight amongst the trees I come out of cover and looked into the cleft. It was kinda like a short blind canyon. It warn’t but about thirty foot wide at the mouth, but it widened quick till it made a kind of bowl a hundred yards acrost, and then narrowed to a crack again. Rock walls five hundred foot high was on all sides except at the mouth.

“And here,” says I to myself, “is a ready-made corral!”

Then I lay to and started to build a wall to close the mouth of the canyon. Later on I heard that a scientific expedition (whatever the hell that might be) was all excited over finding evidences of a ancient race up in the mountains. They said they found a wall that could of been built only by giants. They was crazy; that there was the wall I built for Cap’n Kidd.

I knowed it would have to be high and solid if I didn’t want Cap’n Kidd to jump it or knock it down. They was plenty of boulders laying at the foot of the cliffs which had weathered off, and I didn’t use a single rock which weighed less’n three hundred pounds, and most of ’em was a lot heavier than that. It taken me most all morning, but when I quit I had me a wall higher’n the average man could reach, and so thick and heavy I knowed it would hold even Cap’n Kidd.

I left a narrer gap in it, and piled some boulders close to it on the outside, ready to shove ’em into the gap. Then I stood outside the wall and squalled like a cougar. They ain’t even a cougar hisself can tell the difference when I squalls like one. Purty soon I heard Cap’n Kidd give his war-neigh off yonder, and then they was a thunder of hoofs and a snapping and crackling of bresh, and he come busting into the open with his ears laid back and his teeth bare and his eyes as red as a Comanche’s war-paint. He sure hated cougars. But he didn’t seem to like me much neither. When he seen me he give a roar of rage, and come for me lickety-split. I run through the gap and hugged the wall inside, and he come thundering after me going so fast he run clean across the bowl before he checked hisself. Before he could get back to the gap I’d run outside and was piling rocks in it. I had a good big one about the size of a fat hawg and I jammed it in the gap first and piled t’others on top of it.

Cap’n Kidd arriv at the gap all hoofs and teeth and fury, but it was already filled too high for him to jump and too solid for him to tear down. He done his best, but all he done was to knock some chunks offa the rocks with his heels. He sure was mad. He was the maddest hoss I ever seen, and when I got up on the wall and he seen me, he nearly busted with rage.

He went tearing around the bowl, kicking up dust and neighing like a steamboat on the rampage, and then he come back and tried to kick the wall down again. When he turned to gallop off I jumped offa the wall and landed square on his back, but before I could so much as grab his mane he throwed me clean over the wall and I landed in a cluster of boulders and cactus and skun my shin. This made me mad so I got the lariat and the saddle and clumb back on the wall and roped him, but he jerked the rope out of my hand before I could get any kind of a purchase, and went bucking and pitching around all over the bowl trying to get shet of the rope. So purty soon he pitched right into the cliff-wall and he lammed it so hard with his hind hoofs that a whole section of overhanging rock was jolted loose and hit him right between the ears. That was too much even for Cap’n Kidd.

It knocked him down and stunned him, and I jumped down into the bowl and before he could come to I had my saddle on to him, and a hackamore I’d fixed out of a piece of my lariat. I’d also mended the girths with pieces of the lariat, too, before I built the wall.

Well, when Cap’n Kidd recovered his senses and riz up, snorting and war-like, I was on his back. He stood still for a instant like he was trying to figger out jest what the hell was the matter, and then he turned his head and seen me on his back. The next instant I felt like I was astraddle of a ring-tailed cyclone.

I dunno what all he done. He done so many things all at onst I couldn’t keep track. I clawed leather. The man which could have stayed onto him without clawing leather ain’t born yet, or else he’s a cussed liar. Sometimes my feet was in the stirrups and sometimes they warn’t, and sometimes they was in the wrong stirrups. I cain’t figger out how that could be, but it was so. Part of the time I was in the saddle and part of the time I was behind it on his rump, or on his neck in front of it. He kept reching back trying to snap my laig and onst he got my thigh between his teeth and would ondoubtedly of tore the muscle out if I hadn’t shook him loose by beating him over the head with my fist.

One instant he’d have his head betwixt his feet and I’d be setting on a hump so high in the air I’d get dizzy, and the next thing he’d come down stiff-laiged and I could feel my spine telescoping. He changed ends so fast I got sick at my stummick and he nigh unjointed my neck with his sunfishing. I calls it sunfishing because it was more like that than anything. He occasionally rolled over and over on the ground, too, which was very uncomfortable for me, but I hung on, because I was afeared if I let go I’d never get on him again. I also knowed that if he ever shaken me loose I’d had to shoot him to keep him from stomping my guts out. So I stuck, though I’ll admit that they is few sensations more onpleasant than having a hoss as big as Cap’n Kidd roll on you nine or ten times.

He tried to scrape me off agen the walls, too, but all he done was scrape off some hide and most of my pants, though it was when he lurched agen that outjut of rock that I got them ribs cracked, I reckon.

He looked like he was able to go on forever, and aimed to, but I hadn’t never met nothing which could outlast me, and I stayed with him, even after I started bleeding at the nose and mouth and ears, and got blind, and then all to onst he was standing stock still in the middle of the bowl, with his tongue hanging out about three foot, and his sweat-soaked sides heaving, and the sun was just setting over the mountains. He’d bucked nearly all afternoon!

But he was licked. I knowed it and he knowed it. I shaken the stars and sweat and blood out of my eyes and dismounted by the simple process of pulling my feet out of the stirrups and falling off. I laid there for maybe a hour, and was most amazing sick, but so was Cap’n Kidd. When I was able to stand on my feet I taken the saddle and the hackamore off and he didn’t kick me nor nothing. He jest made a half-hearted attempt to bite me but all he done was to bite the buckle offa my gunbelt. They was a little spring back in the cleft where the bowl narrered in the cliff, and plenty of grass, so I figgered he’d be all right when he was able to stop blowing and panting long enough to eat and drink.

I made a fire outside the bowl and cooked me what was left of the b’ar meat, and then I lay down on the ground and slept till sunup.