Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

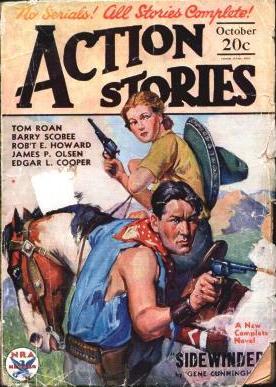

Published in Action Stories, Vol. 12, No. 10 (October 1934).

The folks on Bear Creek ain’t what you’d call peaceable by nature, but I was kind of surprised to come onto Erath Elkins and his brother-in-law Joel Gordon locked in mortal combat on the bank of the creek. But there they was, so tangled up they couldn’t use their bowies to no advantage, and their cussing was scandalous to hear.

Remonstrances being useless, I kicked their knives out of their hands and throwed ’em bodily into the creek. That broke their holds and they come swarming out with blood-thirsty shrieks and dripping whiskers, and attacked me. Seeing they was too blind mad to have any sense, I bashed their heads together till they was too dizzy to do anything but holler.

“Is this any way for relatives to ack?” I asked disgustedly.

“Lemme at him!” howled Joel, gnashing his teeth whilst blood streamed down his whiskers. “He’s broke three of my fangs and I’ll have his life!”

“Stand aside, Breckinridge!” raved Erath. “No man can chaw a ear offa me and live to tell the tale!”

“Aw, shut up,” I snorted. “One more yap outa either’n of you, and I’ll see if yore fool heads are harder’n this.” I brandished a fist under their noses and they quieted down. “What’s all this about?” I demanded.

“I just discovered my brother-in-law is a thief,” said Joel bitterly. At that Erath give a howl and a vi’lent plunge to get at his relative, but I kind of pushed him backwards, and he fell over a willer stump.

“The facts is, Breckinridge,” said Joel, “me and this polecat found a buckskin poke full of gold nuggets in a holler oak over on Apache Ridge yesterday. We didn’t know whether somebody in these parts had just hid it there for safe-keepin’, or whether some old prospector had left it there a long time ago and maybe got sculped by the Injuns and never come back to git it. We agreed to leave it alone for a month, and if it was still there at that time, we’d feel purty shore that the original owner was dead, and we’d split the gold between us. Well, last night I got to worryin’ somebody’d find it which wasn’t as honest as me, so this mornin’ I thought I better go see if it was still there. . . .”

At this point Erath laughed bitterly.

Joel glared at him ominously and continued: “Well, no sooner I hove in sight of the holler tree than this skunk let go at me from the bresh with a rifle-gun—”

“That’s a lie!” yelped Erath. “It war jest the other way around!”

“Not bein’ armed, Breckinridge,” Joel said with dignity, “and realizin’ that this coyote was tryin’ to murder me so he could claim all the gold, I legged it for home and my weppins. And presently I sighted him sprintin’ through the bresh after me.”

Erath begun to foam slightly at the mouth. “I warn’t chasin’ you,” he said. “I was goin’ home after my rifle-gun.”

“What’s yore story, Erath?” I inquired.

“Last night I drempt somebody had stole the gold,” he answered sullenly. “This mornin’ I went to see if it was safe. Just as I got to the tree, this murderer begun shootin’ at me with a Winchester. I run for my life, and by some chance I finally run right into him. Likely he thought he’d kilt me and was comin’ for the sculp.”

“Did either one of you see t’other’n shoot at you?” I asked.

“How could I, with him hid in the bresh?” snapped Joel. “But who else could it been?”

“I didn’t have to see him,” growled Erath. “I felt the wind of his slug.”

“But each one of you says he didn’t have no rifle,” I said.

“He’s a cussed liar,” they accused simultaneous, and would have fell on each other tooth and nail if they could have got past my bulk.

“I’m convinced they’s been a mistake,” I said. “Git home and cool off.”

“You’re too big for me to lick, Breckinridge,” said Erath. “But I warn you, if you cain’t prove to me that it wasn’t Joel which tried to murder me, I ain’t goin’ to rest nor sleep nor eat till I’ve nailed his mangy sculp to the highest pine on Apache Ridge.”

“That goes for me, too,” said Joel, grinding his teeth. “I’m declarin’ truce till tomorrer mornin’. If Breckinridge cain’t show me by then that you didn’t shoot at me, either my wife or yore’n’ll be a widder before midnight.”

So saying they stalked off in opposite directions, whilst I stared helplessly after ’em, slightly dazed at the responsibility which had been dumped onto me. That’s the drawback of being the biggest man in your settlement. All the relatives pile their troubles onto you. Here it was up to me to stop what looked like the beginnings of a regular family feud which was bound to reduce the population awful.

The more I thought of the gold them idjits had found, the more I felt like I ought to go and take a look to see was it real stuff, so I went back to the corral and saddled Cap’n Kidd and lit out for Apache Ridge, which was about a mile away. From the remarks they’d let fell whilst cussing each other, I had a purty good idea where the holler oak was at, and sure enough I found it without much trouble. I tied Cap’n Kid and clumb up on the trunk till I reached the holler. And then as I was craning my neck to look in, I heard a voice say: “Another dern thief!”

I looked around and seen Uncle Jeppard Grimes p’inting a gun at me.

“Bear Creek is goin’ to hell,” said Uncle Jeppard. “First it was Erath and Joel, and now it’s you. I’m goin’ to throw a bullet through yore hind laig just to teach you a little honesty.”

With that he started sighting along the barrel of his Winchester, and I said: “You better save yore lead for that Injun over there.”

Him being a old Indian fighter he just naturally jerked his head around quick, and I pulled my .45 and shot the rifle out of his hands. I jumped down and, put my foot on it, and he pulled a knife out of his boot, and I taken it away from him and shaken him till he was so addled when I let him go he run in a circle and fell down cussing something terrible.

“Is everybody on Bear Creek gone crazy?” I demanded. “Can’t a man look into a holler tree without gettin’ assassinated?”

“You was after my gold,” swore Uncle Jeppard.

“So it’s your gold, hey?” I said. “Well, a holler tree ain’t no bank.”

“I know it,” he growled, combing the pine-needles out of his whiskers. “When I come here early this mornin’ to see if it was safe, like I frequent does, I seen right off somebody’d been handlin’ it. Whilst I was meditatin’ over this, I seen Joel Gordon sneakin’ towards the tree. I fired a shot across his bows in warnin’ and he run off. But a few minutes later here come Erath Elkins slitherin’ through the pines. I was mad by this time, so I combed his whiskers with a chunk of lead and he high-tailed it. And now, by golly, here you come—”

“I don’t want yore blame gold!” I roared. “I just wanted to see if it was safe, and so did Joel and Erath. If them men was thieves, they’d have took it when they found it yesterday. Where’d you get it, anyway?”

“I panned it, up in the hills,” he said sullenly. “I ain’t had time to take it to Chawed Ear and git it changed into cash money. I figgered this here tree was as good a place as any. But I done put it elsewhere now.”

“Well,” I said, “you got to go tell Erath and Joel it was you shot at ’em, so they won’t kill each other. They’ll be mad at you, but I’ll cool ’em off, maybe with a hickory club.”

“All right,” he said. “I’m sorry I misjedged you, Breckinridge. Just to show you I trusts you, I’ll show you whar I hid it.”

He led me through the trees till he come to a big rock jutting out from the side of a cliff, and pointed at a smaller stone wedged beneath it.

“I pulled out that rock,” he said, “and dug a hole and stuck the poke in. Look!”

He heaved the rock out and bent down. And then he went straight up in the air with a yell that made me jump and pull my gun with cold sweat busting out all over me.

“What’s the matter with you?” I demanded. “Are you snake-bit?”

“Yeah, by human snakes!” he hollered. “It’s gone! I been robbed!”

I looked and seen the impressions the wrinkles in the buckskin poke had made in the soft earth. But there wasn’t nothing there now.

Uncle Jeppard was doing a scalp dance with a gun in one hand and a bowie knife in the other’n. “I’ll fringe my leggins with their mangy sculps!” he raved. “I’ll pickle their hearts in a barr’l of brine! I’ll feed their livers to my houn’ dawgs!”

“Whose livers?” I inquired.

“Whose, you idjit?” he howled. “Joel Gordon and Erath Elkins, dern it! They didn’t run off. They snuck back and seen me move the gold! I’ve kilt better men than them for half as much!”

“Aw,” I said, “t’ain’t possible they stole yore gold—”

“Then where is it?” he demanded bitterly. “Who else knowed about it?”

“Look here!” I said, pointing to a belt of soft loam near the rocks. “A horse’s tracks.”

“What of it?” he demanded. “Maybe they had horses tied in the bresh.”

“Aw, no,” I said. “Look how the calkins is set. They ain’t no horses on Bear Creek shod like that. These is the tracks of a stranger—I bet the feller I seen ride past my cabin just about daybreak. A black-whiskered man with one ear missin’. That hard ground by the big rock don’t show where he got off and stomped around, but the man which rode this horse stole yore gold, I’ll bet my guns.”

“I ain’t convinced,” said Uncle Jeppard. “I’m goin’ home and ile my rifle-gun, and then I’m goin’ to go over and kill Joel and Erath.”

“Now you lissen,” I said forcibly. “I know what a stubborn old jassack you are, Uncle Jeppard, but this time you got to lissen to reason or I’ll forget myself and kick the seat outa yore britches. I’m goin’ to follow this feller and take yore gold away from him, because I know it was him stole it. And don’t you dare to kill nobody till I git back.”

“I’ll give you till tomorrer mornin’,” he compromised. “I won’t pull a trigger till then. But,” said Uncle Jeppard waxing poetical, “if my gold ain’t in my hands by the time the mornin’ sun h’ists itself over the shinin’ peaks of the Jackass Mountains, the buzzards will rassle their hash on the carcasses of Joel Gordon and Erath Elkins.”

I went away from there, mounted Cap’n Kidd and headed west on the trail of the stranger. It was still tolerably early in the morning, and one of them long summer days ahead of me. They wasn’t a horse in the Humbolts to equal Cap’n Kidd for endurance. I’ve rode a hundred miles on him between sun-down and sun-up. But that horse the stranger was riding must have been some chunk of horse-meat hisself. The day wore on, and still I hadn’t come up with my man. I was getting into country I wasn’t familiar with, but I didn’t have much trouble in following the trail, and finally, late in the evening, I come out on a narrow dusty path where the calk-marks of his hoofs was very plain.

The sun sunk lower and my hopes dwindled. Cap’n Kidd was beginning to tire, and even if I got the thief and got the gold, it’d be a awful push to get back to Bear Creek in time to prevent mayhem. But I urged on Cap’n Kidd, and presently we come out onto a road, and the tracks I was following merged with a lot of others. I went on, expecting to come to some settlement, and wondering just where I was. I’d never been that far in that direction before then.

Just at sun-down I rounded a bend in the road and seen something hanging to a tree, and it was a man. There was another man in the act of pinning something to the corpse’s shirt, and when he heard me he wheeled and jerked his gun—the man, I mean, not the corpse. He was a mean looking cuss, but he wasn’t Black Whiskers. Seeing I made no hostile move, he put up his gun and grinned.

“That feller’s still kickin’,” I said.

“We just strung him up,” said the fellow. “The other boys has rode back to town, but I stayed to put this warnin’ on his buzzum. Can you read?”

“No,” I said.

“Well,” he said, “this here paper says: ‘Warnin’ to all outlaws and specially them on Grizzly Mountain—Keep away from Wampum.’ ”

“How far’s Wampum from here?” I asked.

“Half a mile down the road,” he said. “I’m Al Jackson, one of Bill Ormond’s deputies. We aim to clean up Wampum. This is one of them derned outlaws which has denned up on Grizzly Mountain.”

Before I could say anything I heard somebody breathing quick and gaspy, and they was a patter of bare feet in the bresh, and a kid girl about fourteen years old bust into the road.

“You’ve killed Uncle Joab!” she shrieked. “You murderers! A boy told me they was fixin’ to hang him! I run as fast as I could—”

“Git away from that corpse!” roared Jackson, hitting at her with his quirt.

“You stop that!” I ordered. “Don’t you hit that young ’un.”

“Oh, please, Mister!” she wept, wringing her hands. “You ain’t one of Ormond’s men. Please help me! He ain’t dead—I seen him move!”

Waiting for no more I spurred alongside the body and drawed my knife.

“Don’t you cut that rope!” squawk the deputy, jerking his gun. So I hit him under the jaw and knocked him out of his saddle and into the bresh beside the road where he lay groaning. I then cut the rope and eased the hanged man down on my saddle and got the noose offa his neck. He was purple in the face and his eyes was closed and his tongue lolled out, but he still had some life in him. Evidently they didn’t drop him, but just hauled him up to strangle to death.

I laid him on the ground and work over him till some of his life begun to come back to him, but I knowed he ought to have medical attention. I said: “Where’s the nearest doctor?”

“Doc Richards in Wampum,” whimpered the kid. “But if we take him there Ormond will get him again. Won’t you please take him home?”

“Where you-all live?” I inquired.

“We been livin’ in a cabin on Grizzly Mountain since Ormond run us out of Wampum,” she whimpered.

“Well,” I said, “I’m goin’ to put yore uncle on Cap’n Kidd and you can set behind the saddle and help hold him on, and tell me which way to go.”

So I done so and started off on foot leading Cap’n Kidd in the direction the girl showed me, and as we went I seen the deputy Jackson drag hisself out of the bresh and go limping down the road holding his jaw.

I was losing a awful lot of time, but I couldn’t leave this feller to die, even if he was a outlaw, because probably the little gal didn’t have nobody to take care of her but him. Anyway, I’d never make it back to Bear Creek by daylight on Cap’n Kidd, even if I could have started right then.

It was well after dark when we come up a narrow trail that wound up a thickly timbered mountain side, and purty soon somebody in a thicket ahead of us hollered: “Halt whar you be or I’ll shoot!”

“Don’t shoot, Jim!” called the girl. “This is Ellen, and we’re bringin’ Uncle Joab home.”

A tall hard-looking young feller stepped out in the open, still p’inting his Winchester at me. He cussed when he seen our load.

“He ain’t dead,” I said. “But we ought to git him to his cabin.”

So Jim led me through the thickets until we come into a clearing where they was a cabin, and a woman come running out and screamed like a catamount when she seen Joab. Me and Jim lifted him off and carried him in and laid him on a bunk, and the women begun to work over him, and I went out to my horse, because I was in a hurry to get gone. Jim follered me.

“This is the kind of stuff we’ve been havin’ ever since Ormond come to Wampum,” he said bitterly. “We been livin’ up here like rats, afeard to stir in the open. I warned Joab against slippin’ down into the village today, but he was sot on it, and wouldn’t let any of the boys go with him. Said he’d sneak in, git what he wanted and sneak out again.”

“Well,” I said, “what’s yore business is none of mine. But this here life is hard lines on women and children.”

“You must be a friend of Joab’s,” she said. “He sent a man east some days ago, but we was afraid one of Ormond’s men trailed him and killed him. But maybe he got through. Are you the man Joab sent for?”

“Meanin’ am I some gunman come in to clean up the town?” I snorted. “Naw, I ain’t. I never seen this feller Joab before.”

“Well,” said Jim, “cuttin’ down Joab like you done has already got you in bad with Ormond. Help us run them fellers out of the country! There’s still a good many of us in these hills, even if we have been run out of Wampum. This hangin’ is the last straw. I’ll round up the boys tonight, and we’ll have a show-down with Ormond’s men. We’re outnumbered, and we been licked bad once, but we’ll try it again. Won’t you throw in with us?”

“Lissen,” I said, climbing into the saddle, “just because I cut down a outlaw ain’t no sign I’m ready to be one myself. I done it just because I couldn’t stand to see the little gal take on so. Anyway, I’m lookin’ for a feller with black whiskers and one ear missin’ which rides a roan with a big Lazy-A brand.”

Jim fell back from me and lifted his rifle. “You better ride on,” he said somberly. “I’m obleeged to you for what you’ve did—but a friend of Wolf Ashley cain’t be no friend of our’n.”

I give him a snort of defiance and rode off down the mountain and headed for Wampum, because it was reasonable to suppose that maybe I’d find Black Whiskers there.

Wampum wasn’t much of a town, but they was one big saloon and gambling hall where sounds of hilarity was coming from, and not many people on the streets and them which was mostly went in a hurry. I stopped one of them and ast him where a doctor lived, and he pointed out a house where he said Doc Richards lived, so I rode up to the door and knocked, and somebody inside said: “What you want? I got you covered.”

“Are you Doc Richards?” I said, and he said: “Yes, keep your hands away from your belt or I’ll fix you.”

“This is a nice, friendly town!” I snorted. “I ain’t figgerin’ on harmin’ you. They’s a man up in the hills which needs yore attention.”

At that the door opened and a man with red whiskers and a shotgun stuck his head out and said: “Who do you mean?”

“They call him Joab,” I said. “He’s on Grizzly Mountain.”

“Hmmmm!” said Doc Richards, looking at me very sharp where I sot Cap’n Kidd in the starlight. “I set a man’s jaw tonight, and he had a lot to say about a certain party who cut down a man that was hanged. If you’re that party, my advice to you is to hit the trail before Ormond catches you.”

“I’m hungry and thirsty and I’m lookin’ for a man,” I said. “I aim to leave Wampum when I’m good and ready.”

“I never argue with a man as big as you,” said Doc Richards. “I’ll ride to Grizzly Mountain as quick as I can get my horse saddled. If I never see you alive again, which is very probable, I’ll always remember you as the biggest man I ever saw, and the biggest fool. Good night!”

I thought, the folks in Wampum is the queerest acting I ever seen. I took my horse to the barn which served as a livery stable and seen that he was properly fixed. Then I went into the big saloon which was called the Golden Eagle. I was low in my spirits because I seemed to have lost Black Whiskers’ trail entirely, and even if I found him in Wampum, which I hoped, I never could make it back to Bear Creek by sun-up. But I hoped to recover that derned gold yet, and get back in time to save a few lives.

They was a lot of tough looking fellers in the Golden Eagle drinking and gambling and talking loud and cussing, and they all stopped their noise as I come in, and looked at me very fishy. But I give ’em no heed and went to the bar, and purty soon they kinda forgot about me and the racket started up again.

Whilst I was drinking me a few fingers of whisky, somebody shouldered up to me and said: “Hey!” I turned around and seen a big, broad-built man with a black beard and blood-shot eyes and a pot-belly with two guns on.

I said: “Well?”

“Who air you?” he demanded.

“Who air you?” I come back at him.

“I’m Bill Ormond, sheriff of Wampum,” he said. “That’s who!” And he showed me a star on his shirt.

“Oh,” I said. “Well, I’m Breckinridge Elkins, from Bear Creek.”

I noticed a kind of quiet come over the place, and fellows was laying down their glasses and their billiard sticks, and hitching up their belts and kinda gathering around me. Ormond scowled and combed his beard with his fingers, and rocked on his heels and said: “I got to ’rest you!”

I sot down my glass quick and he jumped back and hollered: “Don’t you dast pull no gun on the law!” And they was a kind of movement amongst the men around me.

“What you arrestin’ me for?” I demanded. “I ain’t busted no law.”

“You assaulted one of my deputies,” he said, and then I seen that feller Jackson standing behind the sheriff, with his jaw all bandaged up. He couldn’t work his chin to talk. All he could do was p’int his finger at me and shake his fists.

“You likewise cut down a outlaw we had just hunged,” said Ormond. “Yore under arrest!”

“But I’m lookin’ for a man!” I protested. “I ain’t got time to be arrested!”

“You should of thunk about that when you busted the law,” opined Ormond. “Gimme yore gun and come along peaceable.”

A dozen men had their hands on their guns, but it wasn’t that which made me give in. Pap had always taught me never to resist no officer of the law, so it was kind of instinctive for me to hand my gun over to Ormond and go along with him without no fight. I was kind of bewildered and my thoughts was addled anyway. I ain’t one of these fast thinking sharps.

Ormond escorted me down the street a ways, with a whole bunch of men following us, and stopped at a log building with barred windows which was next to a board shack. A man come out of this shack with a big bunch of keys, and Ormond said he was the jailer. So they put me in the log jail and Ormond went off with everybody but the jailer, who sat down on the step outside the shack and rolled a cigaret.

There wasn’t no light in the jail, but I found the bunk and tried to lay down on it, but it wasn’t built for a man six and a half foot tall. I sot down on it and at last realized what a infernal mess I was in. Here I ought to be hunting Black Whiskers and getting the gold to take back to Bear Creek and save the lives of a lot of my kin-folks, but instead I was in jail, and no way of getting out without killing a officer of the law. With daybreak Joel and Erath would be at each other’s throats, and Uncle Jeppard would be gunning for both of ’em. It was too much to hope that the other relatives would let them three fight it out amongst theirselves. I never seen such a clan for butting into each other’s business. The guns would be talking all up and down Bear Creek, and the population would be decreasing with every volley. I thought about it till I got dizzy, and then the jailer stuck his head up to the window and said if I would give him five dollars he’d go get me something to eat.

I give it to him, and he went off and was gone quite a spell, and at last he come back and give me a ham sandwich. I ast him was that all he could get for five dollars, and he said grub was awful high in Wampum. I et the sandwich in one bite, because I hadn’t et nothing since morning, and then he said if I’d give him some more money he’d get me another sandwich. But I didn’t have no more and told him so.

“What!” he said, breathing licker fumes in my face through the window bars. “No money? And you expect us to feed you for nothin’?” So he cussed me, and went off. Purty soon the sheriff come and looked in at me and said: “What’s this I hear about you not havin’ no money?”

“I ain’t got none left,” I said, and he cussed something fierce.

“How you expect to pay yore fine?” he demanded. “You think you can lay up in our jail and eat us out of house and home? What kind of a critter are you, anyway?” Just then the jailer chipped in and said somebody told him I had a horse down at the livery stable.

“Good,” said the sheriff. “We’ll sell the horse for his fine.”

“No, you won’t neither,” I said, beginning to get mad. “You try to sell Cap’n Kidd, and I’ll forgit what pap told me about officers, and take you plumb apart.”

I riz up and glared at him through the window, and he fell back and put his hand on his gun. But just about that time I seen a man going into the Golden Eagle which was in easy sight of the jail, and lit up so the light streamed out into the street. I give a yell that made Ormond jump about a foot. It was Black Whiskers!

“Arrest that man, Sheriff!” I hollered. “He’s a thief!”

Ormond whirled and looked, and then he said: “Are you plumb crazy? That’s Wolf Ashley, my deperty.”

“I don’t give a dern,” I said. “He stole a poke of gold from my Uncle Jeppard up in the Humbolts, and I’ve trailed him clean from Bear Creek. Do yore duty and arrest him.”

“You shut up!” roared Ormond. “You can’t tell me my business! I ain’t goin’ to arrest my best gunman—my star deperty, I mean. What you mean tryin’ to start trouble this way? One more yap outa you and I’ll throw a chunk of lead through you.”

And he turned and stalked off muttering: “Poke of gold, huh? Holdin’ out on me is he? I’ll see about that!”

I sot down and held my head in bewilderment. What kind of a sheriff was this which wouldn’t arrest a derned thief? My thoughts run in circles till my wits was addled. The jailer had gone off and I wondered if he had went to sell Cap’n Kidd. I wondered what was going on back at Bear Creek, and I shivered to think what would bust loose at daybreak. And here I was in jail, with them fellers fixing to sell my horse whilst that derned thief swaggered around at large. I looked helplessly out the window.

It was getting late, but the Golden Eagle was still going full blast. I could hear the music blaring away, and the fellers yipping and shooting their pistols in the air, and their boot heels stomping on the board walk. I felt like busting down and crying, and then I begun to get mad. I get mad slow, generally, and before I was plumb mad, I heard a noise at the window.

I seen a pale face staring in at me, and a couple of small white hands on the bars.

“Oh, Mister!” a voice whispered. “Mister!”

I stepped over and looked out and it was the kid girl Ellen.

“What you doin’ here, gal?” I asked.

“Doc Richards said you was in Wampum,” she whispered. “He said he was afraid Ormond and his gang would go for you, because you helped me, so I slipped away on his horse and rode here as hard as I could. Jim was out tryin’ to gather up the boys for a last stand, and Aunt Rachel and the other women was busy with Uncle Joab. They wasn’t nobody but me to come, but I had to! You saved Uncle Joab, and I don’t care if Jim does say you’re a outlaw because you’re a friend of Wolf Ashley. Oh, I wisht I wasn’t just a girl! I wisht I could shoot a gun, so’s I could kill Bill Ormond!”

“That ain’t no way for a gal to talk,” I said. “Leave killin’ to the men. But I appreciates you goin’ to all this trouble. I got some kid sisters myself—in fact I got seven or eight, as near as I remember. Don’t you worry none about me. Lots of men gets throwed in jail.”

“But that ain’t it!” she wept, wringing her hands. “I listened outside the winder of the back room in the Golden Eagle and heard Ormond and Ashley talkin’ about you. I dunno what you wanted with Ashley when you ast Jim about him, but he ain’t your friend. Ormond accused him of stealin’ a poke of gold and holdin’ out on him, and Ashley said it was a lie. Then Ormond said you told him about it, and that he’d give Ashley till midnight to perdooce that gold, and if he didn’t Wampum would be too small for both of ’em.

“Then he went out and I heard Ashley talkin’ to a pal of his, and Ashley said he’d have to raise some gold somehow, or Ormond would have him killed, but that he was goin’ to fix you, Mister, for lyin’ about him. Mister, Ashley and his bunch are over in the back of the Golden Eagle right now plottin’ to bust into the jail before daylight and hang you!”

“Aw,” I said, “the sheriff wouldn’t let ’em do that.”

“You don’t understand!” she cried. “Ormond ain’t the sheriff! Him and his gunmen come into Wampum and killed all the people that tried to oppose him, or run ’em up into the hills. They got us penned up there like rats, nigh starvin’ and afeared to come to town. Uncle Joab come into Wampum this mornin’ to git some salt, and you seen what they done to him. He’s the real sheriff; Ormond is just a bloody outlaw. Him and his gang is usin’ Wampum for a hang-out whilst they rob and steal and kill all over the country.”

“Then that’s what yore friend Jim meant,” I said slowly. “And me, like a dumb damn fool, I thought him and Joab and the rest of you-all was just outlaws, like that fake deputy said.”

“Ormond took Uncle Joab’s badge and called hisself the sheriff to fool strangers,” she whimpered. “What honest people is left in Wampum are afeared to oppose him. Him and his gunmen are rulin’ this whole part of the country. Uncle Joab sent a man east to git us some help in the settlements on Buffalo River, but none never come, and from what I overheard tonight, I believe Wolf Ashley follered him and killed him over east of the Humbolts somewheres. What are we goin’ to do?” she sobbed.

“Ellen,” I said, “you git on Doc Richards’ horse and ride for Grizzly Mountain. When you git there, tell the Doc to head for Wampum, because there’ll be plenty of work for him time he gits there.”

“But what about you?” she cried. “I can’t go off and leave you to be hanged!”

“Don’t worry about me, gal,” I said. “I’m Breckinridge Elkins of the Humbolt Mountains, and I’m preparin’ for to shake my mane! Hustle!”

Something about me evidently convinced her, because she glided away, whimpering, into the shadows, and presently I heard the clack of horse’s hoofs dwindling in the distance. I then riz and I laid hold of the window bars and tore them out by the roots. Then I sunk my fingers into the sill log and tore it out, and three or four more, and the wall give way entirely and the roof fell down on me, but I shook aside the fragments and heaved up out of the wreckage like a bear out of a deadfall.

About this time the jailer come running up, and when he seen what I had did he was so surprised he forgot to shoot me with his pistol. So I taken it away from him and knocked down the door of his shack with him and left him laying in its ruins.

I then strode up the street toward the Golden Eagle and here come a feller galloping down the street. Who should it be but that derned fake deperty, Jackson? He couldn’t holler with his bandaged jaw, but when he seen me he jerked loose his lariat and piled it around my neck, and sot spurs to his cayuse aiming for to drag me to death. But I seen he had his rope tied fast to his horn, Texas style, so I laid hold on it with both hands and braced my legs, and when the horse got to the end of the rope, the girths busted and the horse went out from under the saddle, and Jackson come down on his head in the street and laid still.

I throwed the rope off my neck and went on to the Golden Eagle with the jailer’s .45 in my scabbard. I looked in and seen the same crowd there, and Ormond r’ared back at the bar with his belly stuck out, roaring and bragging.

I stepped in and hollered: “Look this way, Bill Ormond, and pull iron, you dirty thief!”

He wheeled, paled, and went for his gun, and I slammed six bullets into him before he could hit the floor. I then throwed the empty gun at the dazed crowd and give one deafening roar and tore into ’em like a mountain cyclone. They begun to holler and surge onto me and I throwed ’em and knocked ’em right and left like ten pins. Some was knocked over the bar and some under the tables and some I knocked down stacks of beer kegs with. I ripped the roulette wheel loose and mowed down a whole row of them with it, and I throwed a billiard table through the mirror behind the bar just for good measure. Three or four fellers got pinned under it and yelled bloody murder.

But I didn’t have no time to un-pin ’em, for I was busy elsewhere. Four of them hellions come at me in a flyin’ wedge and the only thing to do was give them a dose of their own medicine. So I put my head down and butted the first one in the belly. He gave a grunt you could hear across the mountains and I grabbed the other three and squoze them together. I then flung them against the bar and headed into the rest of the mess of them. I felt so good I was yellin’ some.

“Come on!” I yelled. “I’m Breckinridge Elkins an’ you got my dander roused.” And I waded in and poured it to ’em.

Meanwhile they was hacking at me with bowies and hitting me with chairs and brass knuckles and trying to shoot me, but all they done with their guns was shoot each other because they was so many they got in each other’s way, and the other things just made me madder. I laid hands on as many as I could hug at once, and the thud of their heads banging together was music to me. I also done good work heaving ’em head-on against the walls, and I further slammed several of ’em heartily against the floor and busted all the tables with their carcasses. In the melee the whole bar collapsed, and the shelves behind the bar fell down when I slang a feller into them, and bottles rained all over the floor. One of the lamps also fell off the ceiling which was beginning to crack and cave in, and everybody begun to yell: “Fire!” and run out through the doors and jump out the windows.

In a second I was alone in the blazing building except for them which was past running. I’d started for a exit myself, when I seen a buckskin pouch on the floor along with a lot of other belongings which had fell out of men’s pockets as they will when the men gets swung by the feet and smashed against the wall.

I picked it up and jerked the tie-string, and a trickle of gold dust spilled into my hand. I begun to look on the floor for Ashley, but he wasn’t there. But he was watching me from outside, because I looked and seen him just as be let bam at me with a .45 from the back room of the place, which wasn’t yet on fire much. I plunged after him, ignoring his next slug which took me in the shoulder, and then I grabbed him and taken the gun away from him. He pulled a bowie and tried to stab me in the groin, but only sliced my thigh, so I throwed him the full length of the room and he hit the wall so hard his head went through the boards.

Meantime the main part of the saloon was burning so I couldn’t go out that way. I started to go out the back door of the room I was in, but got a glimpse of some fellers which was crouching just outside the door waiting to shoot me as I come out. So I knocked out a section of the wall on another side of the room, and about that time the roof fell in so loud them fellers didn’t hear me coming, so I fell on ’em from the rear and beat their heads together till the blood ran out of their ears, and stomped ’em and took their shotguns away from them.

One big fellow with a scarred face tackled me around the knees as I bent over to get the second gun, and a little man hopped on my shoulders from behind at the same time and began clawin’ like a catamount. That made me pretty mad again, but I still kept enough presence of mind not to lose my temper. I just grabbed the little man off and hit Scar Face over the head with him, and after that none of the rest bothered me within hand-holt distance.

Then I was aware that people was shooting at me in the light of the burning saloon, and I seen that a bunch was ganged up on the other side of the street, so I begun to loose my shotguns into the thick of them, and they broke and run yelling blue murder.

And as they went out one side of the town, another gang rushed in from the other, yelling and shooting, and I snapped an empty shell at them before one yelled: “Don’t shoot, Elkins! We’re friends!” And I seen it was Jim and Doc Richards, and a lot of other fellers I hadn’t never seen before then.

They went tearing around, looking to see if any of Ormond’s men was hiding in the village, but none was. They looked like all they wanted to do was get clean out of the country, so most of the Grizzly Mountain men took in after ’em, whoopin’ and shoutin’.

Jim looked at the wreckage of the jail, and the remnants of the Golden Eagle, and he shook his head like he couldn’t believe it.

“We was on our way to make a last effort to take the town back from that gang,” he said. “Ellen met us as we come down and told us you was a friend and a honest man. We hoped to get here in time to save you from gettin’ hanged.” Again he shook his head with a kind of bewildered look. Then he said: “Oh, say, I’d about forgot. On our way here we run onto a man on the road who said he was lookin’ for you. Not knowin’ who he was, we roped him and brung him along with us. Bring the prisoner, boys!”

They brung him, tied to his saddle, and it was Jack Gordon, Joel’s youngest brother and the fastest gun-slinger on Bear Creek.

“What you doin’ here?” I demanded bitterly. “Has the feud begun already and has Joel set you on my trail? Well, I got what I started after, and I’m headin’ back for Bear Creek. I cain’t git there by daylight, but maybe I’ll git there in time to keep everybody from killin’ everybody else. Here’s Uncle Jeppard’s cussed gold!” And I waved the pouch in front of him.

“But that cain’t be it!” he said. “I been trailin’ you all the way from Bear Creek, tryin’ to catch you and tell you the gold had been found! Uncle Jeppard and Joel and Erath got together and everything was explained and is all right. Where’d you git that gold?”

“I dunno whether Ashley’s pals got it together so he could give it to Ormond and not git killed for holdin’ out on his boss, or what,” I said. “But I know that the owner ain’t got no more use for it now, and probably stole it in the first place. I’m givin’ this gold to Ellen,” I said. “She shore deserves a reward. And givin’ it to her makes me feel like maybe I accomplished somethin’ on this wild goose chase, after all.”

Jim looked around at the ruins of the outlaw hang-out, and murmured something I didn’t catch. I said to Jack: “You said Uncle Jeppard’s gold was found? Where was it, anyway?”

“Well,” said Jack, “little General William Harrison Grimes, Uncle Jeppard’s youngster boy, he seen his pap put the gold under the rock, and he got it out to play with it. He was usin’ the nuggets for slugs in his nigger-shooter,” Jack said, “and it’s plumb cute the way he pops a rattlesnake with ’em. What did you say?”

“Nothin’,” I said between my teeth. “Nothin’ that’d be fit to repeat, anyway.”