Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

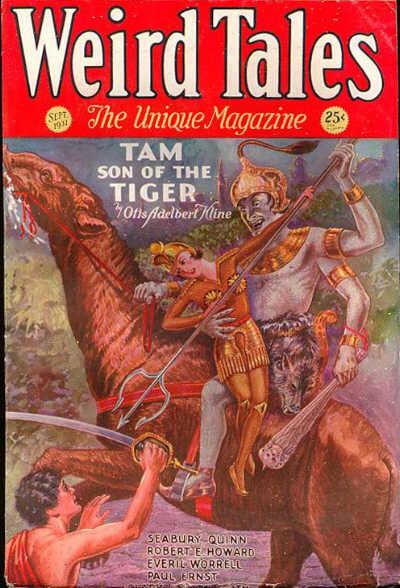

Published in Weird Tales, Vol. 18, No. 2 (September 1931).

Solomon Kane gazed sombrely at the native woman who lay dead at his feet. Little more than a girl she was, but her wasted limbs and staring eyes showed that she had suffered much before death brought her merciful relief. Kane noted the chain galls on her limbs, the deep crisscrossed sears on her back, the mark of the yoke on her neck. His cold eyes deepened strangely, showing chill glints and lights like clouds passing across depths of ice.

“Even into this lonesome land they come,” he muttered. “I had not thought—”

He raised his head and gazed eastward. Black dots against the blue wheeled and circled.

“The kites mark their trail,” muttered the tall Englishman. “Destruction goeth before them and death followeth after. Wo unto ye, sons of iniquity, for the wrath of God is upon ye. The cords be loosed on the iron necks of the hounds of hate and the bow of vengeance is strung. Ye are proud-stomached and strong, and the people cry out beneath your feet, but retribution cometh in the blackness of midnight and the redness of dawn.” He shifted the belt that held his heavy pistols and the keen dirk, instinctively touched the long rapier at his hip, and went stealthily but swiftly eastward. A cruel anger burned in his deep eyes like blue volcanic fires burning beneath leagues of ice, and the hand that gripped his long, cat-headed stave hardened into iron.

After some hours of steady striding, he came within hearing of the slave train that wound its laborious way through the jungle. The piteous cries of the slaves, the shouts and curses of the drivers, and the cracking of the whips came plainly to his ears. Another hour brought him even with them, and gliding along through the jungle parallel to the trail taken by the slavers, he spied upon them safely. Kane had fought Indians in Darien and had learned much of their woodcraft.

More than a hundred natives, young men and women, staggered along the trail, stark naked and made fast together by cruel yoke-like affairs of wood. These yokes, rough and heavy, fitted over their necks and linked them together, two by two. The yokes were in turn fettered together, making one long chain. Of the drivers there were fifteen Arabs and some seventy negro warriors, whose weapons and fantastic apparel showed them to be of some eastern tribe—one of those tribes subjugated and made Moslems and allies by the conquering Arabs.

Five Arabs walked ahead of the train with some thirty of their warriors, and five brought up the rear with the rest of the negro warriors. The rest marched beside the staggering slaves, urging them along with shouts and curses and with long, cruel whips which brought spurts of blood at almost every blow. These slavers were fools as well as rogues, reflected Kane—not more than half of them would survive the hardships of the trek to the coast.

He wondered at the presence of these raiders, for this country lay far to the south of the districts which they usually frequented. But avarice can drive men far, as the Englishman knew. He had dealt with these gentry of old. Even as he watched, old scars burned in his back—scars made by Moslem whips in a Turkish galley. And deeper still burned Kane’s unquenchable hate.

The Puritan followed, shadowing his foes like a ghost, and as he stole through the jungle, he racked his brain for a plan. How might he prevail against that horde? All of the Arabs and many of their allies were armed with guns—long, clumsy firelock affairs, it is true, but guns just the same, enough to awe any tribe of natives who might oppose them. Some carried in their wide girdles long, silver-chased pistols of more effective pattern—flintlocks of Moorish and Turkish make.

Kane followed like a brooding ghost and his rage and hatred ate into his soul like a canker. Each crack of the whips was like a blow on his own shoulders. The heat and cruelty of the tropics play queer tricks. Ordinary passions become monstrous things; irritation runs to a berserker rage; anger flames into unexpected madness and men kill in a red mist of passion, and wonder, aghast, afterward. The fury Solomon Kane felt would have been enough at any time and in any place to shake a man to his foundation. Now it assumed monstrous proportions, so that Kane shivered as if with a chill; iron claws scratched at his brain and he saw the slaves and the slavers through a crimson mist. Yet he might not have put his hate-born insanity into action had it not been for a mishap.

One of the slaves, a slim young girl, suddenly faltered and slipped to the earth, dragging her yoke-mate with her. A tall, hook-nosed Arab yelled savagely and lashed her viciously. Her yoke-mate staggered partly up, but the girl remained prone, writhing weakly beneath the lash but evidently unable to rise. She whimpered pitifully between her parched lips, and other slavers came about her, their whips descending on her quivering flesh in slashes of red agony.

A half hour of rest and a little water would have revived her, but the Arabs had no time to spare. Solomon, biting his arm until his teeth met in the flesh as he fought for control, thanked God that the lashing had ceased and steeled himself for the swift flash of the dagger that would put the child beyond torment. But the Arabs were in a mood for sport. Since the girl would fetch them no profit on the market block, they would utilize her for their pleasure—and their humour was such as to turn men’s blood to icy water.

A shout from the first whipper brought the rest crowding around, their bearded faces split in grins of delighted anticipation, while their savage allies edged nearer, their eyes gleaming. The wretched slaves realized their masters’ intentions and a chorus of pitiful cries rose from them.

Kane, sick with horror, realized, too, that the girl’s was to be no easy death. He knew what the tall Moslem intended to do, as he stooped over her with a keen dagger such as the Arabs used for skinning game. Madness overcame the Englishman. He valued his own life little; he had risked it without thought for the sake of a pagan child or a small animal. Yet he would not have premeditatedly thrown away his one hope of succouring the wretches in the train. But he acted without conscious thought. A pistol was smoking in his hand and the tall butcher was down in the dust of the trail with his brains oozing out, before Kane realized what he had done.

He was almost as astonished as the Arabs, who stood frozen for a moment and then burst into a medley of yells. Several threw up their clumsy firelocks and sent their heavy balls crashing through the trees, and the rest, thinking no doubt that they were ambushed, led a reckless charge into the jungle. The bold suddenness of that move was Kane’s undoing. Had they hesitated a moment longer he might have faded away unobserved, but as it was he saw no choice but to meet them openly and sell his life as highly as he could.

And indeed it was with a certain ferocious fascination that he faced his howling attackers. They halted in sudden amazement as the tall, grim Englishman stepped from behind his tree, and in that instant one of them died with a bullet from Kane’s remaining pistol in his heart. Then with yells of savage rage they flung themselves on their lone defier.

Solomon Kane placed his back against a huge tree and his long rapier played a shining wheel about him. An Arab and three of his equally fiercer allies were hacking at him with their heavy curved blades while the rest milled about, snarling like wolves, as they sought to drive in blade or ball without maiming one of their own number.

The flickering rapier parried the whistling scimitars and the Arab died on its point, which seemed to hesitate in his heart only an instant before it pierced the brain of a sword-wielding warrior. Another attacker dropped his sword and leaped in to grapple at close quarters. He was disembowelled by the dirk in Kane’s left hand, and the others gave back in sudden fear. A heavy ball smashed against the tree close to Kane’s head and he tensed himself to spring and die in the thick of them. Then their sheikh lashed them on with his long whip, and Kane heard him shouting fiercely for his warriors to take the infidel alive. Kane answered the command with a sudden cast of his dirk, which hummed so close to the sheikh’s head that it slit his turban and sank deep in the shoulder of one behind him.

The sheikh drew his silver-chased pistols, threatening his own men with death if they did not take this fierce opponent, and they charged in again desperately. One of the warriors ran full upon Kane’s sword and an Arab behind the fellow, with ruthless craft, thrust the screaming wretch suddenly forward on the weapon, driving it hilt-deep in his writhing body, fouling the blade. Before Kane could wrench it clear, with a yell of triumph the pack rushed in on him and bore him down by sheer weight of numbers. As they grappled him from all sides, the Puritan wished in vain for the dirk he had thrown away. But even so, his taking was none too easy.

Blood spattered and faces caved in beneath his iron-hard fists that splintered teeth and shattered bone. A warrior reeled away disabled from a vicious drive of knee to groin. Even when they had him stretched out and piled man-weight on him, until he could no longer strike with fists or foot, his long lean fingers sank fiercely through a matted beard to lock about a corded throat in a grip that took the power of three strong men to break and left the victim grasping and green-faced.

At last, panting from the terrific struggle, they had him bound hand and foot and the sheikh, thrusting his pistols back into his silken sash, came striding to stand and look down at his captive. Kane glared up at the tall, lean frame, at the hawk-like face with its black-curled beard and arrogant brown eyes.

“I am the sheikh Hassim ben Said,” said the Arab. “Who are you?"

“My name is Solomon Kane,” growled the puritan in the sheikh’s own language. “I am an Englishman, you heathen jackal.”

The dark eyes of the Arab flickered with interest.

“Suleiman Kahani,” said he, giving the Arabesque equivalent of the English name. “I have heard of you—you have fought the Turks betimes and the Barbary corsairs have licked their wounds because of you.” Kane deigned no reply. Hassim shrugged his shoulders.

“You will bring a fine price,” said he. “Mayhap I will take you to Stamboul, where there are Shas who would desire such a man among their slaves. And I mind me now of one Kemal Bey, a man of ships, who wears a deep scar across his face of your making and who curses the name of Englishman. He will pay me a high price for you. And behold, oh Frank, I do you the honour of appointing you a separate guard. You shall not walk in the yoke-chain but free save for your hands.”

Kane made no answer, and at a sign from the sheikh, he was hauled to his feet and his bonds loosened except for his hands, which they left bound firmly behind him. A stout cord was looped about his neck and the other end of this was given into the hand of a huge warrior who bore in his free hand a great curved scimitar.

“And now what think ye of my favour to you, Frank?” queried the sheikh.

“I am thinking,” answered Kane in a slow, deep voice of menace, “that I would trade my soul’s salvation to face you and your sword, alone and unarmed, and to tear the heart from your breast with my naked fingers.”

Such was the concentrated hate in his deep resounding voice, and such primal, unconquerable fury blazed from his terrible eyes, that the hardened and fearless chieftain blanched and involuntarily recoiled as if from a maddened beast.

Then Hassim recovered his poise and with a short word to his followers, strode to the head of the cavalcade. Kane noted with thankfulness that the respite occasioned by his capture had given the girl who had fallen a chance to rest and revive. The skinning knife had not had time to more than touch her; she was able to reel along. Night was not far away. Soon the slavers would be forced to halt and camp.

The Englishman perforce took up the trek, his guard remaining a few paces behind with a huge blade ever ready. Kane also noted with a touch of grim vanity, that three more warriors marched close behind, muskets ready and matches burning. They had tasted his prowess and they were taking no chances. His weapons had been recovered and Hassim had promptly appropriated all except the cat-headed ju-ju staff. This had been contemptuously cast aside by him and taken up by one of the savage warriors.

The Englishman was presently aware that a lean, grey-bearded Arab was walking along at his side. This Arab seemed desirous of speaking but strangely timid, and the source of his timidity seemed, curiously enough, the ju-ju stave which he had taken from the man who had picked it up, and which he now turned uncertainly in his hands.

“I am Yussef the Hadji,” said this Arab suddenly. “I have naught against you. I had no hand in attacking you and would be your friend if you would let me. Tell me, Frank, whence comes this staff and how comes it into your hands?”

Kane’s first inclination was to consign his questioner to the infernal regions, but a certain sincerity of manner in the old man made him change his mind and he answered: “It was given me by my blood-brother—a magician of the Slave Coast, named N’Longa.”

The old Arab nodded and muttered in his beard and presently sent a warrior running forward to bid Hassim return. The tall sheikh presently came striding back along the slow-moving column, with a clank and jingle of daggers and sabres, with Kane’s dirk and pistols thrust into his wide sash.

“Look, Hassim,” the old Arab thrust forward the stave, “you cast it away without knowing what you did!”

“And what of it?” growled the sheikh. “I see naught but a staff—sharp-pointed and with the head of a cat on the other end—a staff with strange infidel carvings upon it.”

The older man shook it at him in excitement: “This staff is older than the world! It holds mighty magic! I have read of it in the old iron-bound books and Mohammed—on whom peace!—himself hath spoken of it by allegory and parable! See the cat-head upon it? It is the head of a goddess of ancient Egypt! Ages ago, before Mohammed taught, before Jerusalem was, the priests of Bast bore this rod before the bowing, chanting worshippers! With it Musa did wonders before Pharaoh and when the Yahudi fled from Egypt they bore it with them. And for centuries it was the sceptre of Israel and Judah and with it Suleiman ben Daoud drove forth the conjurers and magicians and prisoned the efreets and the evil genii! Look! Again in the hands of a Suleiman we find the ancient rod!”

Old Yussef had worked himself into a pitch of almost fanatic fervour but Hassim merely shrugged his shoulders.

“It did not save the Jews from bondage nor this Suleiman from our captivity,” said he. “I value it not as much as I esteem the long thin blade with which he loosed the souls of three of my best swordsmen.”

Yussef shook his head. “Your mockery will bring you to no good end, Hassim. Some day you will meet a power that will not divide before your sword or fall to your bullets. I will keep the staff, and I warn you—abuse not the Frank. He has borne the holy and terrible staff of Suleiman and Musa and the Pharaohs, and who knows what magic he has drawn therefrom? For it is older than the world and has known the terrible hands of strange pre-Adamite priests in the silent cities beneath the seas, and has drawn from an Elder World mystery and magic unguessed by humankind. There were strange kings and stranger priests when the dawns were young, and evil was, even in their day. And with this staff they fought the evil which was ancient when their strange world was young, so many millions of years ago that a man would shudder to count them.” Hassim answered impatiently and strode away with old Yussef following him persistently and chattering away in a querulous tone. Kane shrugged his mighty shoulders. With what he knew of the strange powers of that strange staff, he was not one to question the old man’s assertions, fantastic as they seemed.

This much he knew—that it was made of a wood that existed nowhere on earth today. It needed but the proof of sight and touch to realize that its material had grown in some world apart. The exquisite workmanship of the head, of a pre-pyramidal age, and the hieroglyphics, symbols of a language that was forgotten when Rome was young—these, Kane sensed, were additions as modern to the antiquity of the staff itself as would be English words carved on the stone monoliths of Stonehenge.

As for the cat-head—looking at it sometimes Kane had a peculiar feeling of alteration; a faint sensing that once the pommel of the staff was carved with a different design. The dust-ancient Egyptian who had carved the head of Bast had merely altered the original figure, and what that figure had been, Kane had never tried to guess. A close scrutiny of the staff always aroused a disquieting and almost dizzy suggestion of abysses of eons, unprovocative to further speculation.

The day wore on. The sun beat down mercilessly, then screened itself in the great trees as it slanted toward the horizon. The slaves suffered fiercely for water and a continual whimpering rose from their ranks as they staggered blindly on. Some fell and half-crawled, and were half-dragged by their reeling yoke-mates. When all were buckling from exhaustion, the sun dipped, night rushed on, and a halt was called. Camp was pitched, guards thrown out. The slaves were fed scantily and given enough water to keep life in them—but only just enough. Their fetters were not loosened, but they were allowed to sprawl about as they might. Their fearful thirst and hunger having been somewhat eased, they bore the discomforts of their shackles with characteristic stoicism.

Kane was fed without his hands being untied, and he was given all the water he wished. The patient eyes of the slaves watched him drink, silently, and he was sorely ashamed to guzzle what others suffered for; he ceased before his thirst was fully quenched. A wide clearing had been selected, on all sides of which rose gigantic trees. After the Arabs had eaten and while the black Moslems were still cooking their food, old Yussef came to Kane and began to talk about the staff again. Kane answered his questions with admirable patience, considering the hatred he bore the whole race to which the Hadji belonged, and during the conversation, Hassim came striding up and looked down in contempt. Hassim, Kane ruminated, was the very symbol of militant Islam—bold, reckless, materialistic, sparing nothing, fearing nothing, as sure of his own destiny and as contemptuous of the rights of others as the most powerful Western king. “Are you maundering about that stick again?” he gibed. “Hadji, you grow childish in your old age.” Yussef’s beard quivered in anger. He shook the staff at his sheikh like a threat of evil.

“Your mockery little befits your rank, Hassim,” he snapped. “We are in the heart of a dark and demon-haunted land, to which long ago were banished the devils from Arabia, if this staff, which any but a fool can tell is no rod of any world we know, has existed down to our day, who knows what other things, tangible or intangible, may have existed through the ages? This very trail we follow—know you how old it is? Men followed it before the Seljuk came out of the East or the Roman came out of the West. Over this very trail, legends say, the great Suleiman came when he drove the demons westward out of Asia and prisoned them in strange prisons. And will you say—”

A wild shout interrupted him. Out of the shadows of the jungle a warrior came flying as if from the hounds of Doom. With arms flinging wildly, eyes rolling to display the whites, and mouth wide open so that all his gleaming teeth were visible, he made an image of stark terror not soon forgotten. The Moslem horde leaped up, snatching their weapons, and Hassim swore:

“That’s Ali, whom I sent to scout for meat—perchance a lion—”

But no lion followed the man who fell at Hassim’s feet, mouthing gibberish and pointing wildly back at the black jungle whence the nerve-strung watchers expected some brain-shattering horror to burst. “He says he found a strange mausoleum back in the jungle,” said Hassim with a scowl, “but he cannot tell what frightened him. He only knows a great horror overwhelmed him and sent him flying. Ali, you are a fool and a rogue.”

He kicked the grovelling savage viciously, but the other Arabs drew about him in some uncertainty. The panic was spreading among the native warriors.

“They will bolt in spite of us,” muttered a bearded Arab, uneasily watching the native allies who, milled together, jabbered excitedly and flung fearsome glances over the shoulders. “Hassim, ’twere better to march on a few miles. This is an evil place after all, and though ’tis likely the fool, Ali, was frighted by his own shadow—still—”

“Still,” jeered the sheikh, “you will all feel better when we have left it behind. Good enough; to still your fears I will move camp—but first I will have a look at this thing. Lash up the slaves, we’ll swing into the jungle and pass by this mausoleum; perhaps some great king lies there. No one will be afraid if we all go in a body with guns.”

So the weary slaves were whipped into wakefulness and stumbled along beneath the whips again. The native allies went silently and nervously, reluctantly obeying Hassim’s implacable will but huddling close to the Arabs. The moon had risen, huge, red and sullen, and the jungle was bathed in a sinister silver glow that etched the brooding trees in black shadow. The trembling Ali pointed out the way, somewhat reassured by his savage master’s presence. And so they passed through the jungle until they came to a strange clearing among the giant trees—strange because nothing grew there. The trees ringed it in a disquieting symmetrical manner, and no lichen or moss grew on the earth, which seemed to have been blasted and blighted in a strange fashion. And in the midst of the glade stood the mausoleum.

A great brooding mass of stone it was, pregnant with ancient evil. Dead with the dead of a hundred centuries it seemed, yet Kane was aware that the air pulsed about it, as with the slow, unhuman breathing of some gigantic, invisible monster.

The Arab’s native allies drew back muttering, assailed by the evil atmosphere of the place; the slaves stood in a patient, silent group beneath the trees. The Arabs went forward to the frowning black mass, and Yussef, taking Kane’s cord from his guard, led the Englishman with him like a surly mastiff, as if for protection against the unknown.

“Some mighty sultan doubtless lies here,” said Hassim, tapping the stone with his scabbard.

“Whence come these stones?” muttered Yussef uneasily. “They are of dark and forbidding aspect. Why should a great sultan lie in state so far from any habitation of man? If there were ruins of an old city hereabouts it would be different—”

He bent to examine the heavy metal door with its huge lock, curiously sealed and fused. He shook his head forebodingly as he made out the ancient Hebraic characters carved on the door.

“I can not read them,” he quavered, “and belike it is well for me I can not. What ancient kings sealed up is not good for men to disturb. Hassim, let us hence. This place is pregnant with evil for the sons of men.”

But Hassim gave him no heed. “He who lies within is no son of Islam,” said he, “and why should we not despoil him of the gems and riches that undoubtedly were laid to rest with him? Let us break open this door.”

Some of the Arabs shook their heads doubtfully but Hassim’s word was law. Calling to him a huge warrior who bore a heavy hammer, he ordered him to break open the door.

As the man swung up his sledge, Kane gave a sharp exclamation. Was he mad? The apparent antiquity of this brooding mass of stone was proof that it had stood undisturbed for thousands of years. Yet he could have sworn that he heard the sounds of footfalls within! Back and forth they padded, as if something paced the narrow confines of that grisly prison in a never-ending monotony of movement.

A cold hand touched the spine of Solomon Kane. Whether the sounds registered on his conscious ear or on some un-sounded deep of soul or sub-feeling, he could not tell, but he knew that somewhere within his consciousness there re-echoed the tramp of monstrous feet from within that ghastly mausoleum.

“Stop!” he exclaimed. “Hassim, I may be mad, but I hear the tread of some fiend within that pile of stone.” Hassim raised his hand and checked the hovering hammer. He listened intently, and the others strained their ears in a silence that had suddenly become tense.

“I hear nothing,” grunted a bearded giant, “Nor I,” came a quick chorus. “The Frank is mad!”

“Hear ye anything, Yussef?” asked Hassim sardonically.

The old Hadji shifted nervously. His face was uneasy.

“No. Hassim, no, yet—”

Kane decided he must be mad. Yet in his heart he knew he was never saner, and he knew somehow that this occult keenness of the deeper senses that set him apart from the Arabs came from long association with the ju-ju staff that old Yussef now held in his shaking hands.

Hassim laughed harshly and made a gesture to the warrior. The hammer fell with a crash that re-echoed deafeningly and shivered off through the black jungle in a strangely altered cachinnation. Again—again—and again the hammer fell, driven with all the power of rippling muscles and mighty body. And between the blows Kane still heard that lumbering tread, and he who had never known fear as men know it, felt the cold hand of terror clutching at his heart. This fear was apart from earthly or mortal fear, as the sound of the footfalls was apart from mortal tread. Kane’s fright was like a cold wind blowing on him from outer realms of unguessed Darkness, bearing him the evil and decay of an outlived epoch and an unutterably ancient period. Kane was not sure whether he heard those footfalls or by some dim instinct sensed them. But he was sure of their reality. They were not the tramp of man or beast; but inside that black, hideously ancient mausoleum some nameless thing moved with soul-shaking and elephantine tread.

The powerful warrior sweated and panted with the difficulty of his task. But at last, beneath the heavy blows the ancient lock shattered; the hinges snapped; the door burst inward. And Yussef screamed.

From that black gaping entrance no tiger-fanged beast or demon of solid flesh and blood leaped forth. But a fearful stench flowed out in billowing, almost tangible waves and in one brain-shattering, ravening rush, whereby the gaping door seemed to gush blood, the Horror was upon them. It enveloped Hassim, and the fearless chieftain, hewing vainly at the almost intangible terror, screamed with sudden, unaccustomed fright as his lashing simitar whistled only through stuff as yielding and unharmable as air, and he felt himself lapped by coils of death and destruction.

Yussef shrieked like a lost soul, dropped the ju-ju stave and joined his fellows who streamed out into the jungle in mad flight, preceded by their howling allies. Only the slaves fled not, but stood shackled to their doom, wailing their terror. As in a nightmare of delirium Kane saw Hassim swaying like a reed in the wind, lapped about by a gigantic pulsing red Thing that had neither shape nor earthly substance. Then, as the crack of splintering bones came to him, and the sheikh’s body buckled like a straw beneath a stamping hoof, the Englishman burst his bonds with one volcanic effort and caught up the ju-ju stave.

Hassim was down, crushed and dead, sprawled like a broken toy with shattered limbs awry, and the red pulsing Thing was lurching toward Kane like a thick cloud of blood in the air, that continually changed its shape and form, and yet somehow trod lumberingly as if on monstrous legs!

Kane felt the cold fingers of fear claw at his brain, but he braced himself, and lifting the ancient staff, struck with all his power into the centre of the Horror. And he felt an unnameable, immaterial substance meet and give way before the falling staff. Then he was almost strangled by the nauseous burst of unholy stench that flooded the air, and somewhere down the dim vistas of his soul’s consciousness re-echoed unbearably a hideous formless cataclysm that he knew was the death-screaming of the monster. For it was down and dying at his feet, its crimson paling in slow surges like the rise and receding of red waves on some foul coast. And as it paled, the soundless screaming dwindled away into cosmic distances as though it faded into some sphere apart and aloof beyond human ken.

Kane, dazed and incredulous, looked down on a shapeless, colourless, all but invisible mass at his feet which he knew was the corpse of the Horror, dashed back into the black realms from whence it had come, by a single blow of the staff of Solomon. Aye, the same staff, Kane knew, that in the hands of a mighty King and magician had ages ago driven the monster into that strange prison, to bide until ignorant hands loosed it again upon the world.

The old tales were true then, and King Solomon had in truth driven the demons westward and sealed them in strange places. Why had he let them live? Was human magic too weak in those dim days to more than subdue the devils? Kane shrugged his shoulders in wonderment. He knew nothing of magic, yet he had slain where that other Solomon had but imprisoned.

And Solomon Kane shuddered, for he had looked on Life that was not Life as he knew it, and had dealt and witnessed Death that was not Death as he knew it. Again the realization swept over him. as it had in the dust-haunted halls of Atlantean Negari, as it had in the abhorrent Hills of the Dead, as it had in Akaana—that human life was but one of a myriad forms of existence, that worlds existed within worlds, and that there was more than one plane of existence. The planet men call the earth spun on through the untold ages, Kane realized, and as it spun it spawned Life, and living things which wriggled about it as maggots are spawned in not and corruption. Man was the dominant maggot now; why should he in his pride suppose that he and his adjuncts were the first maggots—or the last to rule a planet quick with unguessed life. He shook his head, gazing in new wonder at the ancient gift of N’Longa, seeing in it at last not merely a tool of black magic, but a sword of good and light against the powers of inhuman evil forever. And he was shaken with a strange reverence for it that was almost fear. Then he bent to the Thing at his feet, shuddering to feel its strange mass slip through his fingers like wisps of heavy fog. He thrust the staff beneath it and somehow lifted and levered the mass back into the mausoleum and shut the door.

Then he stood gazing down at the strangely mutilated body of Hassim, noting how it was smeared with foul slime and how it had already begun to decompose. He shuddered again, and suddenly a low timid voice aroused him from his sombre cogitations. The captives knelt beneath the trees and watched with great patient eyes. With a start he shook off his strange mood. He took from the mouldering corpse his own pistols, dirk and rapier, making shift to wipe off the clinging foulness that was already flecking the steel with rust. He also took up a quantity of powder and shot dropped by the Arabs in their frantic flight. He knew they would return no more. They might die in their flight, or they might gain through the interminable leagues of jungle to the coast; but they would not turn back to dare the terror of that grisly glade.

Kane came to the wretched slaves and after some difficulty released them. “Take up these weapons which the warriors dropped in their haste,” said he, “and get you home. This is an evil place. Get ye back to your villages and when the next Arabs come, die in the ruins of your huts rather than be slaves.”

Then they would have knelt and kissed his feet, but he, in much confusion, forbade them roughly. Then as they made preparations to go, one said to him: “Master, what of thee? Wilt thou not return with us? Thou shalt be our king!”

But Kane shook his head.

“I go eastward,” said he. And so the tribespeople bowed to him and turned back on the long trail to their own homeland. And Kane shouldered the staff that had been the rod of the Pharaohs and of Moses and of Solomon and of nameless Atlantean kings behind them, and turned his face eastward, halting only for a single backward glance at the great mausoleum that other Solomon had built with strange arts so long ago, and which now loomed dark and forever silent against the stars.