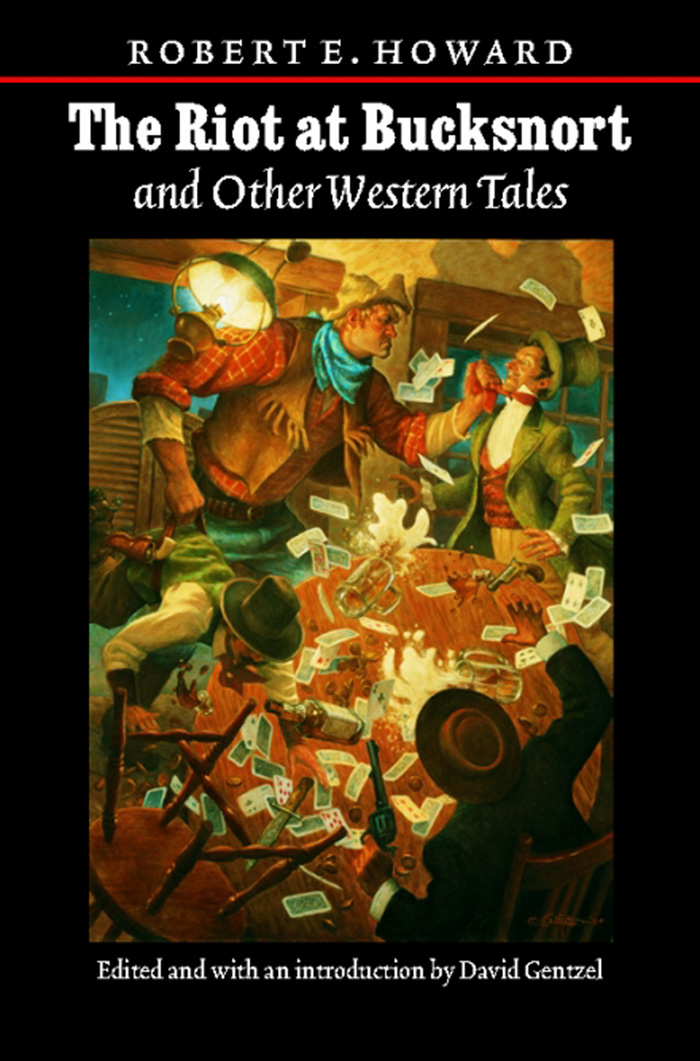

Cover from the collection The Riot at Bucksnort and Other Western Tales (2005).

Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

Published in Action Stories, Vol. 13, No. 2 (June 1935).

These here derned lies which is being circulated around is making me sick and tired. If this slander don’t stop I’m liable to lose my temper, and anybody in the Humbolts can tell you when I loses my temper the effect on the population is wuss’n fire, earthquake, and cyclone.

First-off, it’s a lie that I rode a hundred miles to mix into a feud which wasn’t none of my business. I never heard of the Hopkins-Barlow war before I come in the Mezquital country. I hear tell the Barlows is talking about suing me for destroying their property. Well, they ought to build their cabins solider if they don’t want ’em tore down. And they’re all liars when they says the Hopkinses hired me to exterminate ’em at five dollars a sculp. I don’t believe even a Hopkins would pay five dollars for one of their mangy sculps. Anyway, I don’t fight for hire for nobody. And the Hopkinses needn’t bellyache about me turning on ’em and trying to massacre the entire clan. All I wanted to do was kind of disable ’em so they couldn’t interfere with my business. And my business, from first to last, was defending the family honor. If I had to wipe up the earth with a couple of feuding clans whilst so doing, I can’t help it. Folks which is particular of their hides ought to stay out of the way of tornadoes, wild bulls, devastating torrents, and a insulted Elkins.

But it was Uncle Jeppard Grimes’ fault to begin with, like it generally is. Dern near all the calamities which takes places in southern Nevada can be traced back to that old lobo. He’s got a ingrown disposition and a natural talent for pestering his feller man. Specially his relatives.

I was setting in a saloon in War Paint, enjoying a friendly game of kyards with a horse-thief and three train-robbers, when Uncle Jeppard come in and spied me, and he come over and scowled down on me like I was the missing lynx or something. Purty soon he says, just as I was all sot to make a killing, he says: “How can you set there so free and keerless, with four ace-kyards into yore hand, when yore family name is bein’ besmirched?”

I flang down my hand in annoyance, and said: “Now look what you done! What you mean blattin’ out information of sech a private nature? What you talkin’ about, anyhow?”

“Well,” he says, “durin’ the three months you been away from home roisterin’ and wastin’ yore substance in riotous livin’—”

“I been down on Wild River punchin’ cows at thirty a month!” I said fiercely. “I ain’t squandered nothin’ nowheres. Shut up and tell me whatever yo’re a-talkin’ about.”

“Well,” says he, “whilst you been gone young Dick Jackson of Chawed Ear has been courtin’ yore sister Ellen, and the family’s been expectin’ ’em to set the day, any time. But now I hear he’s been braggin’ all over Chawed Ear about how he done jilted her. Air you goin’ to set there and let yore sister become the laughin’ stock of the country? When I was a young man—”

“When you was a young man Dan’l Boone warn’t whelped yet!” I bellered, so mad I included him and everybody else in my irritation. They ain’t nothing upsets me like injustice done to some of my close kin. “Git out of my way! I’m headin’ for Chawed Ear—what you grinnin’ at, you spotted hyener?” This last was addressed to the horse-thief in which I seemed to detect signs of amusement.

“I warn’t grinnin’,” he said.

“So I’m a liar, I reckon!” I said. I felt a impulse to shatter a demi-john over his head, which I done, and he fell under a table hollering bloody murder, and all the fellers drinking at the bar abandoned their licker and stampeded for the street hollering: “Take cover, boys! Breckinridge Elkins is on the rampage!”

So I kicked all the slats out of the bar to relieve my feelings, and stormed out of the saloon and forked Cap’n Kidd. Even he seen it was no time to take liberties with me—he didn’t pitch but seven jumps—then he settled down to a dead run, and we headed for Chawed Ear.

Everything kind of floated in a red haze all the way, but them folks which claims I tried to murder ’em in cold blood on the road between War Paint and Chawed Ear is just narrer-minded and super-sensitive. The reason I shot everybody’s hats off that I met was just to kind of ca’m my nerves, because I was afraid if I didn’t cool off some by the time I hit Chawed Ear I might hurt somebody. I am that mild-mannered and retiring by nature that I wouldn’t willing hurt man, beast, nor Injun unless maddened beyond endurance.

That’s why I acted with so much self-possession and dignity when I got to Chawed Ear and entered the saloon where Dick Jackson generally hung out.

“Where’s Dick Jackson?” I said, and everybody must of been nervous, because when I boomed out they all jumped and looked around, and the bartender dropped a glass and turned pale.

“Well,” I hollered, beginning to lose patience. “Where is the coyote?”

“G—gimme time, will ya?” stuttered the bar-keep. “I—uh—he—uh—”

“So you evades the question, hey?” I said, kicking the foot-rail loose. “Friend of his’n, hey? Tryin’ to pertect him, hey?” I was so overcome by this perfidy that I lunged for him and he ducked down behind the bar and I crashed into it bodily with all my lunge and weight, and it collapsed on top of him, and all the customers run out of the saloon hollering, “Help, murder, Elkins is killin’ the bartender!”

This feller stuck his head up from amongst the ruins of the bar and begged: “For God’s sake, lemme alone! Jackson headed south for the Mezquital Mountains yesterday.”

I throwed down the chair I was fixing to bust all the ceiling lamps with, and run out and jumped on Cap’n Kidd and headed south, whilst behind me folks emerged from their cyclone cellars and sent a rider up in the hills to tell the sheriff and his deputies they could come on back now.

I knowed where the Mezquitals was, though I hadn’t never been there. I crossed the Californy line about sundown, and shortly after dark I seen Mezquital Peak looming ahead of me. Having ca’med down somewhat, I decided to stop and rest Cap’n Kidd. He warn’t tired, because that horse has got alligator blood in his veins, but I knowed I might have to trail Jackson clean to The Angels, and they warn’t no use in running Cap’n Kidd’s laigs off on the first lap of the chase.

It warn’t a very thickly settled country I’d come into, very mountainous and thick timbered, but purty soon I come to a cabin beside the trail and I pulled up and hollered, “Hello!”

The candle inside was instantly blowed out, and somebody pushed a rifle barrel through the winder and bawled: “Who be you?”

“I’m Breckinridge Elkins from Bear Creek, Nevada,” I said. “I’d like to stay all night, and git some feed for my horse.”

“Stand still,” warned the voice. “We can see you agin the stars, and they’s four rifle-guns a-kiverin’ you.”

“Well, make up yore minds,” I said, because I could hear ’em discussing me. I reckon they thought they was whispering. One of ’em said: “Aw, he can’t be a Barlow. Ain’t none of ’em that big.” T’other’n said: “Well, maybe he’s a derned gun-fighter they’ve sent for to help ’em out. Old Jake’s nephew’s been up in Nevady.”

“Le’s let him in,” said a third. “We can mighty quick tell what he is.”

So one of ’em come out and ’lowed it would be all right for me to stay the night, and he showed me a corral to put Cap’n Kidd in, and hauled out some hay for him.

“We got to be keerful,” he said. “We got lots of enemies in these hills.”

We went into the cabin, and they lit the candle again, and sot some corn pone and sow-belly and beans on the table and a jug of corn licker. They was four men, and they said their names was Hopkins—Jim, Bill, Joe, and Joshua, and they was brothers. I’d always heard tell the Mezquital country was famed for big men, but these fellers wasn’t so big—not much over six foot high apiece. On Bear Creek they’d been considered kind of puny and undersized.

They warn’t very talkative. Mostly they sot with their rifles acrost their knees and looked at me without no expression onto their faces, but that didn’t stop me from eating a hearty supper, and would of et a lot more only the grub give out; and I hoped they had more licker somewheres else because I was purty dry. When I turned up the jug to take a snort of it was brim-full, but before I’d more’n dampened my gullet the dern thing was plumb empty.

When I got through I went over and sot down on a raw-hide bottomed chair in front of the fire-place where they was a small fire going, though they warn’t really no need for it, and they said: “What’s yore business, stranger?”

“Well,” I said, not knowing I was going to get the surprize of my life, “I’m lookin’ for a feller named Dick Jackson—”

By golly, the words wasn’t clean out of my mouth when they was four men onto my neck like catamounts!

“He’s a spy!” they hollered. “He’s a cussed Barlow! Shoot him! Stab him! Hit him in the head!”

All of which they was endeavoring to do with such passion they was getting in each other’s way, and it was only his over-eagerness which caused Jim to miss me with his bowie and sink it into the table instead, but Joshua busted a chair over my head and Bill would of shot me if I hadn’t jerked back my head so he just singed my eyebrows. This lack of hospitality so irritated me that I riz up amongst ’em like a b’ar with a pack of wolves hanging onto him, and commenced committing mayhem on my hosts, because I seen right off they was critters which couldn’t be persuaded to respect a guest no other way.

Well, the dust of battle hadn’t settled, the casualities was groaning all over the place, and I was just re-lighting the candle when I heard a horse galloping down the trail from the south. I wheeled and drawed my guns as it stopped before the cabin. But I didn’t shoot, because the next instant they was a bare-footed gal standing in the door. When she seen the rooins she let out a screech like a catamount.

“You’ve kilt ’em!” she screamed. “You murderer!”

“Aw, I ain’t neither,” I said. “They ain’t hurt much—just a few cracked ribs, and dislocated shoulders and busted laigs and sech-like trifles. Joshua’s ear’ll grow back on all right, if you take a few stitches into it.”

“You cussed Barlow!” she squalled, jumping up and down with the hystericals. “I’ll kill you! You damned Barlow!”

“I ain’t no Barlow,” I said. “I’m Breckinridge Elkins, of Bear Creek. I ain’t never even heard of no Barlows.”

At that Jim stopped his groaning long enough to snarl: “If you ain’t a friend of the Barlows, how come you askin’ for Dick Jackson? He’s one of ’em.”

“He jilted my sister!” I roared. “I aim to drag him back and make him marry her!”

“Well, it was all a mistake,” groaned Jim. “But the damage is done now.”

“It’s wuss’n you think,” said the gal fiercely. “The Hopkinses has all forted theirselves over at pap’s cabin, and they sent me to git you all. We got to make a stand. The Barlows is gatherin’ over to Jake Barlow’s cabin, and they aims to make a foray onto us tonight. We was outnumbered to begin with, and now here’s our best fightin’ men laid out! Our goose is cooked plumb to hell!”

“Lift me on my horse,” moaned Jim. “I can’t walk, but I can still shoot.” He tried to rise up, and fell back cussing and groaning.

“You got to help us!” said the gal desperately, turning to me. “You done laid out our four best fightin’ men, and you owes it to us. It’s yore duty! Anyway, you says Dick Jackson’s yore enemy—well, he’s Jake Barlow’s nephew, and he come back here to help ’em clean out us Hopkinses. He’s over to Jake’s cabin right now. My brother Bill snuck over and spied on ’em, and he says every fightin’ man of the clan is gatherin’ there. All we can do is hold the fort, and you got to come help us hold it! Yo’re nigh as big as all four of these boys put together.”

Well, I figgered I owed the Hopkinses something, so, after setting some bones and bandaging some wounds and abrasions of which they was a goodly lot, I saddled Cap’n Kidd and we sot out.

As we rode along she said: “That there is the biggest, wildest, meanest-lookin’ critter I ever seen. Where’d you git him?”

“He was a wild horse,” I said. “I catched him up in the Humbolts. Nobody ever rode him but me. He’s the only horse west of the Pecos big enough to carry my weight, and he’s got painter’s blood and a shark’s disposition. What’s this here feud about?”

“I dunno,” she said. “It’s been goin’ on so long everybody’s done forgot what started it. Somebody accused somebody else of stealin’ a cow, I think. What’s the difference?”

“They ain’t none,” I assured her. “If folks wants to have feuds its their own business.”

We was following a winding path, and purty soon we heard dogs barking and about that time the gal turned aside and got off her horse, and showed me a pen hid in the brush. It was full of horses.

“We keep our mounts here so’s the Barlows ain’t so likely to find ’em and run ’em off,” she said, and she turned her horse into the pen, and I put Cap’n Kidd in, but tied him over in one corner by hisself—otherwise he would of started fighting all the other horses and kicked the fence down.

Then we went on along the path and the dogs barked louder and purty soon we come to a big two-story cabin which had heavy board-shutters over the winders. They was just a dim streak of candle light come through the cracks. It was dark, because the moon hadn’t come up. We stopped in the shadder of the trees, and the gal whistled like a whippoorwill three times, and somebody answered from up on the roof. A door opened a crack in the room which didn’t have no light at all, and somebody said: “That you, Elizerbeth? Air the boys with you?”

“It’s me,” says she, starting toward the door. “But the boys ain’t with me.”

Then all to once he throwed open the door and hollered: “Run, gal! They’s a grizzly b’ar standin’ up on his hind laigs right behind you!”

“Aw, that ain’t no b’ar,” says she. “That there’s Breckinridge Elkins, from up in Nevady. He’s goin’ to help us fight the Barlows.”

We went on into a room where they was a candle on the table, and they was nine or ten men there and thirty-odd women and chillern. They all looked kinda pale and scairt, and the men was loaded down with pistols and Winchesters.

They all looked at me kind of dumb-like, and the old man kept staring like he warn’t any too sure he hadn’t let a grizzly in the house, after all. He mumbled something about making a natural mistake, in the dark, and turned to the gal.

“Whar’s the boys I sent you after?” he demanded, and she says: “This gent mussed ’em up so’s they ain’t fitten for to fight. Now, don’t git rambunctious, pap. It war just a honest mistake all around. He’s our friend, and he’s gunnin’ for Dick Jackson.”

“Ha! Dick Jackson!” snarled one of the men, lifting his Winchester. “Just lemme line my sights on him! I’ll cook his goose!”

“You won’t, neither,” I said. “He’s got to go back to Bear Creek and marry my sister Ellen. . . . Well,” I says, “what’s the campaign?”

“I don’t figger they’ll git here till well after midnight,” said Old Man Hopkins. “All we can do is wait for ’em.”

“You means you all sets here and waits till they comes and lays siege?” I says.

“What else?” says he. “Lissen here, young man, don’t start tellin’ me how to conduck a feud. I growed up in this here’n. It war in full swing when I was born, and I done spent my whole life carryin’ it on.”

“That’s just it,” I snorted. “You lets these dern wars drag on for generations. Up in the Humbolts we brings such things to a quick conclusion. Mighty near everybody up there come from Texas, original, and we fights our feuds Texas style, which is short and sweet—a feud which lasts ten years in Texas is a humdinger. We winds ’em up quick and in style. Where-at is this here cabin where the Barlow’s is gatherin’?”

“ ’Bout three mile over the ridge,” says a young feller they called Bill.

“How many is they?” I ast.

“I counted seventeen,” says he.

“Just a fair-sized mouthful for a Elkins,” I said. “Bill, you guide me to that there cabin. The rest of you can come or stay, it don’t make no difference to me.”

Well, they started jawing with each other then. Some was for going and some for staying. Some wanted to go with me and try to take the Barlows by surprize, but the others said it couldn’t be done—they’d git ambushed theirselves, and the only sensible thing to be did was to stay forted and wait for the Barlows to come. They given me no more heed—just sot there and augered.

But that was all right with me. Right in the middle of the dispute, when it looked like maybe the Hopkinses’ would get to fighting amongst theirselves and finish each other before the Barlows could git there, I lit out with the boy Bill, which seemed to have considerable sense for a Hopkins.

He got him a horse out of the hidden corral, and I got Cap’n Kidd, which was a good thing. He’d somehow got a mule by the neck, and the critter was almost at its last gasp when I rescued it. Then me and Bill lit out.

We follered winding paths over thick-timbered mountainsides till at last we come to a clearing and they was a cabin there, with light and profanity pouring out of the winders. We’d been hearing the last mentioned for half a mile before we sighted the cabin.

We left our horses back in the woods a ways, and snuck up on foot and stopped amongst the trees back of the cabin.

“They’re in there tankin’ up on corn licker to whet their appetites for Hopkins blood!” whispered Bill, all in a shiver. “Lissen to ’em! Them fellers ain’t hardly human! What you goin’ to do? They got a man standin’ guard out in front of the door at the other end of the cabin. You see they ain’t no doors nor winders at the back. They’s winders on each side, but if we try to rush it from the front or either side, they’ll see us and fill us full of lead before we could git in a shot. Look! The moon’s comin’ up. They’ll be startin’ on their raid before long.”

I’ll admit that cabin looked like it was going to be harder to storm than I’d figgered. I hadn’t had no idee in mind when I sot out for the place. All I wanted was to get in amongst them Barlows—I does my best fighting at close quarters. But at the moment I couldn’t think of no way that wouldn’t get me shot up. Of course I could just rush the cabin, but the thought of seventeen Winchesters blazing away at me from close range was a little stiff even for me, though I was game to try it, if they warn’t no other way.

Whilst I was studying over the matter, all to once the horses tied out in front of the cabin snorted, and back up the hills something went Oooaaaw-w-w! And a idee hit me.

“Git back in the woods and wait for me,” I told Bill, as I headed for the thicket where we’d left the horses.

I mounted and rode up in the hills toward where the howl had come from. Purty soon I lit and throwed Cap’n Kidd’s reins over his head, and walked on into the deep bresh, from time to time giving a long squall like a cougar. They ain’t a catamount in the world can tell the difference when a Bear Creek man imitates one. After a while one answered, from a ledge just a few hundred feet away.

I went to the ledge and clumb up on it, and there was a small cave behind it, and a big mountain lion in there. He give a grunt of surprize when he seen I was a human, and made a swipe at me, but I give him a bat on the head with my fist, and whilst he was still dizzy I grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and hauled him out of the cave and lugged him down to where I left my horse.

Cap’n Kidd snorted at the sight of the cougar and wanted to kick his brains out, but I give him a good kick in the stummick hisself, which is the only kind of reasoning Cap’n Kidd understands, and got on him and headed for the Barlow hangout.

I can think of a lot more pleasant jobs than toting a full-growed mountain lion down a thick-timbered mountain side on the back of a iron jaw outlaw at midnight. I had the cat by the back of the neck with one hand, so hard he couldn’t squall, and I held him out at arm’s length as far from the horse as I could, but every now and then he’d twist around so he could claw Cap’n Kidd with his hind laigs, and when this would happen Cap’n Kidd would squall with rage and start bucking all over the place. Sometimes he would buck the derned cougar onto me, and pulling him loose from my hide was wuss’n pulling cockle-burrs out of a cow’s tail.

But presently I arriv close behind the cabin. I whistled like a whippoorwill for Bill, but he didn’t answer and warn’t nowheres to be seen, so I decided he’d got scairt and pulled out for home. But that was all right with me. I’d come to fight the Barlows, and I aimed to fight ’em, with or without assistance. Bill would just of been in the way.

I got off in the trees back of the cabin and throwed the reins over Cap’n Kidd’s head, and went up to the back of the cabin on foot, walking soft and easy. The moon was well up, by now, and what wind they was, was blowing toward me, which pleased me, because I didn’t want the horses tied out in front to scent the cat and start cutting up before I was ready.

The fellers inside was still cussing and talking loud as I approached one of the winders on the side, and one hollered out: “Come on! Let’s git started! I craves Hopkins gore!” And about that time I give the cougar a heave and throwed him through the winder.

He let out a awful squall as he hit, and the fellers in the cabin hollered louder’n he did. Instantly a most awful bustle broke loose in there and of all the whooping and bellering and shooting I ever heard, and the lion squalling amongst it all, and clothes and hides tearing so you could hear it all over the clearing, and the horses busting loose and tearing out through the bresh.

As soon as I hove the cat I run around to the door and a man was standing there with his mouth open, too surprized at the racket to do anything. So I takes his rifle away from him and broke the stock off on his head, and stood there at the door with the barrel intending to brain them Barlows as they run out. I was plumb certain they would run out, because I have noticed that the average man is funny that way, and hates to be shut up in a cabin with a mad cougar as bad as the cougar would hate to be shut up in a cabin with a infuriated settler of Bear Creek.

But them scoundrels fooled me. ’Pears like they had a secret door in the back wall, and whilst I was waiting for them to storm out through the front door and get their skulls cracked, they knocked the secret door open and went piling out that way.

By the time I realized what was happening and run around to the other end of the cabin, they was all out and streaking for the trees, yelling blue murder, with their clothes all tore to shreds and them bleeding like stuck hawgs.

That there catamount sure improved the shining hours whilst he was corralled with them Barlows. He come out after ’em with his mouth full of the seats of men’s britches, and when he seen me he give a kind of despairing yelp and taken out up the mountain with his tail betwixt his laigs like the devil was after him with a red-hot branding iron.

I taken after the Barlows, sot on scuttling at least a few of ’em, and I was on the p’int of letting bam at ’em with my six-shooters as they run, when, just as they reached the trees, all the Hopkins men riz out of the bresh and fell on ’em with piercing howls.

That fray was kind of peculiar. I don’t remember a single shot being fired. The Barlows had dropped their guns in their flight, and the Hopkinses seemed bent on whipping out their wrongs with their bare hands and gun butts. For a few seconds they was a hell of a scramble—men cussing and howling and bellering, and rifle-stocks cracking over heads, and the bresh crashing underfoot, and then before I could get into it, the Barlows broke every which-way and took out through the woods like jack-rabbits squalling Jedgment Day.

Old Man Hopkins come prancing out of the bresh waving his Winchester and his beard flying in the moonlight and he hollered: “The sins of the wicked shall return onto ’em! Elkins, we have hit a powerful lick for righteousness this here night!”

“Where’d you all come from?” I ast. “I thought you was still back in yore cabin chawin’ the rag.”

“Well,” he says, “after you pulled out we decided to trail along and see how you come out with whatever you planned. As we come through the woods expectin’ to git ambushed every second, we met Bill here who told us he believed you had a idee of circumventin’ them devils, though he didn’t know what it was. So we come on and hid ourselves at the aidge of the trees to see what’d happen. I see we been too timid in our dealin’s with these heathens. We been lettin’ them force the fightin’ too long. You was right. A good offense is the best defense.

“We didn’t kill any of the varmints, wuss luck,” he said, “but we give ’em a prime lickin’. Hey, look there! The boys has caught one of the critters! Take him into that cabin, boys!”

They lugged him into the cabin, and by the time me and the old man got there, they had the candles lit, and a rope around the Barlow’s neck and one end throwed over a rafter.

That cabin was a sight, all littered with broke guns and splintered chairs and tables, pieces of clothes and strips of hide. It looked just about like a cabin ought to look where they has just been a fight between seventeen polecats and a mountain lion. It was a dirt floor, and some of the poles which helped hold up the roof was splintered, so most of the weight was resting on a big post in the center of the hut.

All the Hopkinses was crowding around their prisoner, and when I looked over their shoulders and seen the feller’s pale face in the light of the candle I give a yell: “Dick Jackson!”

“So it is!” said Old Man Hopkins, rubbing his hands with glee. “So it is! Well, young feller, you got any last words to orate?”

“Naw,” said Jackson sullenly. “But if it hadn’t been for that derned lion spilin’ our plans we’d of had you danged Hopkinses like so much pork. I never heard of a cougar jumpin’ through a winder before.”

“That there cougar didn’t jump,” I said, shouldering through the mob. “He was hev. I done the heavin’.”

His mouth fell open and he looked at me like he’d saw the ghost of Sitting Bull. “Breckinridge Elkins!” says he. “I’m cooked now, for sure!”

“I’ll say you air!” gritted the feller who’d spoke of shooting Jackson earlier in the night. “What we waitin’ for? Le’s string him up.”

The rest started howlin’.

“Hold on,” I said. “You all can’t hang him. I’m goin’ to take him back to Bear Creek.”

“You ain’t neither,” said Old Man Hopkins. “We’re much obleeged to you for the help you’ve give us tonight, but this here is the first chance we’ve had to hang a Barlow in fifteen year, and we aim to make the most of it. String him, boys!”

“Stop!” I roared, stepping for’ard.

In a second I was covered by seven rifles, whilst three men laid hold of the rope and started to heave Jackson’s feet off the floor. Them seven Winchesters didn’t stop me. But for one thing I’d of taken them guns away and wiped up the floor with them ungrateful mavericks. But I was afeared Jackson would get hit in the wild shooting that was certain to foller such a plan of action.

What I wanted to do was something which would put ’em all horse-de-combat as the French say, without killing Jackson. So I laid hold on the center-post and before they knowed what I was doing, I tore it loose and broke it off, and the roof caved in and the walls fell inwards on the roof.

In a second they wasn’t no cabin at all—just a pile of lumber with the Hopkinses all underneath and screaming blue murder. Of course I just braced my laigs and when the roof fell my head busted a hole through it, and the logs of the falling walls hit my shoulders and glanced off, so when the dust settled I was standing waist-deep amongst the ruins and nothing but a few scratches to show for it.

The howls that riz from beneath the ruins was blood-curdling, but I knowed nobody was hurt permanent because if they was they wouldn’t be able to howl like that. But I expect some of ’em would of been hurt if my head and shoulders hadn’t kind of broke the fall of the roof and wall-logs.

I located Jackson by his voice, and pulled pieces of roof board and logs off until I come onto his laig, and I pulled him out by it and laid him on the ground to get his wind back, because a beam had fell acrost his stummick and when he tried to holler he made the funniest noise I ever heard.

I then kind of rooted around amongst the debris and hauled Old Man Hopkins out, and he seemed kind of dazed and kept talking about earthquakes.

“You better git to work extricatin’ yore misguided kin from under them logs, you hoary-haired old sarpent,” I told him sternly. “After that there display of ingratitude I got no sympathy for you. In fact, if I was a short-tempered man I’d feel inclined to violence. But bein’ the soul of kindness and generosity, I controls my emotions and merely remarks that if I wasn’t mild-mannered as a lamb, I’d hand you a boot in the pants—like this!”

I kicked him gentle.

“Owww!” says he, sailing through the air and sticking his nose to the hilt in the dirt. “I’ll have the law on you, you derned murderer!” He wept, shaking his fists at me, and as I departed with my captive I could hear him chanting a hymn of hate as he pulled chunks of logs off of his bellering relatives.

Jackson was trying to say something, but I told him I warn’t in no mood for perlite conversation and the less he said the less likely I was to lose my temper and tie his neck into a knot around a black jack.

Cap’n Kidd made the hundred miles from the Mezquital Mountains to Bear Creek by noon the next day, carrying double, and never stopping to eat, sleep, nor drink. Them that don’t believe that kindly keep their mouths shet. I have already licked nineteen men for acting like they didn’t believe it.

I stalked into the cabin and throwed Dick Jackson down on the floor before Ellen which looked at him and me like she thought I was crazy.

“What you finds attractive about this coyote,” I said bitterly, “is beyond the grasp of my dust-coated brain. But here he is, and you can marry him right away.”

She said: “Air you drunk or sun-struck? Marry that good-for-nothin’, whiskey-swiggin’, card-shootin’ loafer? Why, ain’t been a week since I run him out of the house with a buggy whip.”

“Then he didn’t jilt you?” I gasped.

“Him jilt me?” she said. “I jilted him!”

I turned to Dick Jackson more in sorrer than in anger.

“Why,” said I, “did you boast all over Chawed Ear about jiltin’ Ellen Elkins?”

“I didn’t want folks to know she turned me down,” he said sulkily. “Us Jacksons is proud. The only reason I ever thought about marryin’ her was I was ready to settle down, on the farm pap gave me, and I wanted to marry me a Elkins gal so I wouldn’t have to go to the expense of hirin’ a couple of hands and buyin’ a span of mules and—”

They ain’t no use in Dick Jackson threatening to have the law on me. He got off light to what’s he’d have got if pap and my brothers hadn’t all been off hunting. They’ve got terrible tempers. But I was always too soft-hearted for my own good. In spite of Dick Jackson’s insults I held my temper. I didn’t do nothing to him at all, except escort him in sorrow for five or six miles down the Chawed Ear trail, kicking the seat of his britches.