Background Colour: -White- -NavajoWhite- -Wheat- -Beige- -AntiqueWhite- -LightGray- -Silver- -BurlyWood- -Tan- -Black- -Blue-

Text Colour: -Black- -Brown- -Blue- -Green- -Red- -Yellow- -White- -Orange- -Silver-

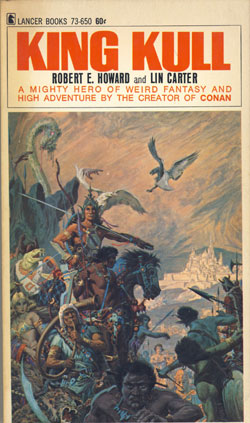

Published in King Kull, 1967.

“All ready, Kull—Khor-nah; let us eat.”

The speaker was young—little more than a boy: a tall, slim-waisted, broad-shouldered lad who moved with the easy grace of a leopard. Of his companions, one was an older man, a powerful, massively-built, hairy man with an aggressive face. The other was a counterpart of the speaker, except for the fact that he was slightly larger—taller, a thought deeper of chest and broader of shoulder. He gave the impression, even more than the first youth, of dynamic speed concealed in long, smooth muscles.

“Good,” said he, “I am hungry.”

“When were you ever otherwise, Kull?” jeered the first speaker.

“When I am fighting,” Kull answered seriously.

The other shot a quick glance at his friend so as to fathom his inmost mind; he was not always sure of his friend.

“And then you are blood-hungry,” broke in the older man. “Am-ra, have done with your bantering and cut us food.”

Night began to fall; the stars blinked out. Over the shadowy hill country swept the dusk wind. Far off, a tiger roared suddenly. Khor-nah made an instinctive motion toward the flint-pointed spear which lay beside him. Kull turned his head, and a strange light flickered in his cold gray eyes.

“The striped brothers hunt tonight,” said he.

“They worship the rising moon,” Am-ra indicated the east where a red radiance was becoming evident.

“Why?” asked Kull. “The moon discloses them to their prey and their enemies.”

“Once, many hundreds of years ago,” said Khor-nah, “a king tiger, pursued by hunters, called on the woman in the moon, and she flung him down a vine whereby he climbed to safety and abode for many years in the moon. Since then, all the striped people worship the moon.”

“I don’t believe it,” said Kull bluntly. “Why should the striped people worship the moon for aiding one of their race who died so long ago? Many a tiger has scrambled up Death Cliff and escaped the hunters, but they do not worship that cliff. How should they know what took place so long ago?”

Khor-nah’s brow clouded. “It little becomes you, Kull, to jeer at your elders or to mock the legends of your adopted people. This tale must be true, because it has been handed down from generation unto generation longer than men remember. What always was, must always be.”

“I don’t believe it,” reiterated Kull. “These mountains always were, but someday they will crumble and vanish. Someday the sea will flow over these hills—”

“Enough of this blasphemy!” cried Khor-nah with a passion that was almost anger. “Kull, we are close friends, and I bear with you because of your youth; but one thing you must learn: respect for tradition. You mock at the customs and ways of our people; you whom that people rescued from the wilderness and gave a home and a tribe.”

“I was a hairless ape roaming in the woods,” admitted Kull frankly and without shame. “I could not speak the language of men, and my only friends were the tigers and the wolves. I know not whom my people were, or what blood am I—”

“That matters not,” broke in Khor-nah. “For all you have the aspect of one of that outlaw tribe who lived in Tiger Valley, and who perished in the Great Flood, it matters little. You have proven yourself a valiant warrior and a mighty hunter—”

“Where will you find a youth to equal him in throwing the spear or in wrestling?” broke in Am-ra, his eyes alight.

“Very true,” said Khor-nah. “He is a credit to the Sea-mountain tribe, but for all that, he must control his tongue and learn to reverence the holy things of the past and of the present.”

“I mock not,” said Kull without malice. “But many things the priests say I know to be lies, for I have run with the tigers and I know wild beasts better than the priests. Animals are neither gods nor fiends, but men in their way without the lust and greed of the man—”

“More blasphemy!” cried Khor-nah angrily. “Man is Valka’s mightiest creation.”

Am-ra broke in to change the subject. “I heard the coast drums beating early in the morning. There is war on the sea. Valusia fights the Lemurian pirates.”

“Evil luck to both,” grunted Khor-nah.

Kull’s eyes flickered again. “Valusia! Land of Enchantment! Someday I will see the great City of Wonder.”

“Evil the day that you do,” snarled Khor-nah. “You will be loaded with chains, with the doom of torture and death hanging over you. No man of our race sees the Great City save as a slave.”

“Evil luck attend her,” muttered Am-ra.

“Black luck and a red doom!” exclaimed Khor-nah, shaking his fist toward the east. “For each drop of spilt Atlantean blood, for each slave toiling in their cursed galleys, may a black blight rest on Valusia and all the Seven Empires!”

Am-ra, fired, leaped lithely to his feet and repeated part of the curse; Kull cut himself another slice of cooked meat.

“I have fought the Valusians,” said he. “And they were bravely arrayed but not hard to kill. Nor were they evil featured.”

“You fought the feeble guard of her northern coast,” grunted Khor-nah. “Or the crew of stranded merchant ships. Wait until you have faced the charge of the Black Squadrons, or the Great Army, as have I. Hai! Then there is blood to drink! With Gandaro of the Spear, I harried the Valusian coasts when I was younger than you, Kull. Aye, we carried the torch and the sword deep into the empire. Five hundred men we were, of all the coast tribes of Atlantis. Four of us returned! Outside the village of Hawks, which we burned and sacked, the van of the Black Squadrons smote us. Hai, there the spears drank and the swords were eased of thirst! We slew and they slew, but when the thunder of battle was stilled, four of us escaped from the field, and all of us sore wounded.”

“Ascalante tells me,” pursued Kull, “that the walls about the Crystal City are ten times the height of a tall man; that the gleam of gold and silver would dazzle the eyes, and the women who throng the streets or lean from their windows are robed in strange, smooth robes that rustle and sheen.”

“Ascalante should know,” grimly said Khor-nah, “since he was slave among them so long that he forgot his good Atlantean name and must forsooth abide by the Valusian name they gave him.”

“He escaped,” commented Am-ra.

“Aye, but for every slave that escapes the clutches of the Seven Empires, seven are rotting in dungeons and dying each day, for it was not meant for an Atlantean to bide as a slave.”

“We have been enemies to the Seven Empires since the dawn of time,” mused Am-ra.

“And will be until the world crashes,” said Khor-nah with a savage satisfaction. “For Atlantis, thank Valka, is the foe of all men,”

Am-ra rose, taking his spear, and prepared to stand watch. The other two lay down on the sward and dropped off to sleep. Of what did Khor-nah dream? Battle perhaps, or the thunder of buffalo, or a girl of the caves. Kull—

Through the mists of his sleep echoed faintly and far away the golden melody of the trumpets. Clouds of radiant glory floated over him; then a mighty vista opened before his dream self. A great concourse of people stretched away into the distance, and a thunderous roar in a strange language went up from them. There was a minor note of steel clashing, and great shadowy armies reined to the right and the left; the mist faded, and a face stood out boldly, a face above which hovered a regal crown—a hawk-like face, dispassionate, immobile, with eyes like the gray of the cold sea. Now the people thundered again; “Hail the king! Hail the king! Kull the king!”

Kull awoke with a start—the moon glimmered on the distant mountains, the wind sighed through the tall grass. Khor-nah slept beside him and Am-ra stood, a naked bronze statue against the stars. Kull’s eyes wandered to his scanty garment: a leopard’s hide twisted about his pantherish loins. A naked barbarian—Kull’s cold eyes glimmered. Kull the king! Again he slept.

They arose in the morning and set out for the caves of the tribe. The sun was not yet high when the broad blue river met their gaze and the caverns of the tribe rose to view.

“Look!” Am-ra cried out sharply. “They burn someone!”

A heavy stake stood before the caves; thereon was a young girl bound. The people who stood about, hard-eyed, showed no sign of pity.

“Sareeta,” said Khor-nah, his face setting into unbending lines. “She married a Lemurian pirate, the wanton.”

“Aye,” broke in a stony-eyed old woman. “My own daughter; thus she brought shame on Atlantis. My daughter no longer! Her mate died; she was washed ashore when their ship was broken by the craft of Atlantis.”

Kull eyed the girl compassionately. He could not understand—why did these people, her own kind and blood, frown on her so, merely because she chose an enemy of her race? In all the eyes that were centered on her, Kull saw only one trace of sympathy. Am-ra’s strange blue eyes were sad and compassionate.

What Kull’s own immobile face mirrored there is no knowing. But the eyes of the doomed girl rested on his. There was no fear in her eyes, but a deep and vibrant appeal. Kull’s gaze wandered to the fagots at her feet. Soon the priest, who now chanted a curse beside her, would stoop and light these with the torch which he now held in his left hand. Kull saw that she was bound to the stake with a heavy wooden chain, a peculiar thing which was typically Atlantean in its manufacture. He could not sever that chain, even if he reached her through the throng that barred his way.

Her eyes implored him. He glanced at the fagots, touched the long flint dagger at his girdle. She understood, nodded, relief flooding her eyes.

Kull struck as suddenly and unexpectedly as a cobra. He snatched the dagger from his girdle and threw it. Fairly under the heart it struck, killing her instantly. While the people stood spellbound, Kull wheeled, bounded away, and ran up the sheer side of the cliff for twenty feet, like a cat. The people stood, struck dumb; then a man whipped up bow and arrow and sighted along the smooth shaft. Kull was heaving himself over the lip of the cliff; the bowman’s eyes narrowed—Am-ra, as if by accident, lurched headlong into him, and the arrow sang wide and aside. Then Kull was gone.

He heard the screaming on his track; his own tribesmen, fired with the blood-lust, wild to run him down and slay him for violating their strange and bloody code of morals. But no man in Atlantis could outrun Kull of the Sea-mountain tribe.

Kull eludes his infuriated tribesmen, only to fall captive to the Lemurians, For the next two years he toils as a slave at the oars of a galley, before escaping. He makes his way to Valusia, where he becomes an outlaw in the hills, until captured and confined in her dungeons. Fortune smiles upon him; he becomes, successively, a gladiator in the arena, a soldier in the army, and a commander. Then, with the backing of the mercenaries and certain discontented Valusian noblemen, he strikes for the throne. Kull it is who slays the despotic King Borna and rips the crown from his gory head. The dream has become reality; Kull of Atlantis sits enthroned in ancient Valusia.